Participation and Democracy: Dynamics, Causes ... - Jacobs University

Participation and Democracy: Dynamics, Causes ... - Jacobs University

Participation and Democracy: Dynamics, Causes ... - Jacobs University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Participation</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Democracy</strong>:<br />

<strong>Dynamics</strong>, <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>and</strong> Consequences of<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities<br />

by<br />

Franziska Deutsch<br />

a Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment<br />

of the requirements for the degree of<br />

Doctor of Philosophy in<br />

Political Science<br />

Approved Dissertation Committee<br />

Prof. Dr. Christian Welzel<br />

Prof. Dr. Klaus Boehnke<br />

Prof. Dr. Ferdin<strong>and</strong> Müller-Rommel<br />

Date of Defense: 29.06.2009<br />

School of Humanities <strong>and</strong> Social Sciences

Acknowledgement<br />

Writing this PhD thesis was a long process that would not have been possible without the<br />

help <strong>and</strong> support of many others:<br />

First <strong>and</strong> foremost, I’d like to thank Chris Welzel for encouraging me to pursue an<br />

academic career <strong>and</strong> a PhD under his supervision. His generous support <strong>and</strong> his curiosity<br />

<strong>and</strong> enthusiasm for research have been motivation <strong>and</strong> inspiration. Most valuably, he has<br />

introduced me to the potentials of survey research <strong>and</strong> especially to the fascinating world<br />

of the World Values Survey.<br />

I also want to thank Klaus Boehnke <strong>and</strong> Ferdin<strong>and</strong> Müller-Rommel for their support <strong>and</strong><br />

for agreeing to become members of my dissertation committee.<br />

Furthermore, I thank my colleagues Nicola Bücker, Yuliya Salauyova, Daniel Fuss <strong>and</strong><br />

Bernhard Gißibl for their encouragement <strong>and</strong> friendship <strong>and</strong> for sharing this special time<br />

in our lives. I’d like to thank Julian Wucherpfennig for his assistance <strong>and</strong> our stimulating<br />

discussions. I am also grateful to Matthijs Bogaards for his encouraging words <strong>and</strong><br />

helpful academic advice.<br />

Finally, I want to thank my family <strong>and</strong> friends: Over the past years, Jana Steinert, Claus<br />

Hilgetag, Holger Kenn, Antonia Gohr <strong>and</strong> Steffi Markert have supported, consoled,<br />

advised <strong>and</strong> encouraged me. I am grateful for their friendship.<br />

My family has been my greatest source of comfort <strong>and</strong> strength. I would like to thank my<br />

parents <strong>and</strong> brothers for their unbelievable unconditional love <strong>and</strong> support.

Declaration:<br />

I herewith declare that this thesis is my own work <strong>and</strong> that I have used only the sources<br />

listed. No part of this thesis has been accepted or is currently being submitted for any<br />

degree or other qualification at this university or elsewhere.<br />

Franziska Deutsch Bremen, 04 June 2009

CONTENTS<br />

Figures <strong>and</strong> Tables<br />

Introduction 1<br />

A<br />

Theoretical Considerations<br />

1 Elite-Challenging Activities as Political <strong>Participation</strong> 9<br />

2 Theoretical Framework: What Explains <strong>Dynamics</strong>, <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

Consequences of Elite-Challenging Activities? 15<br />

2.1 Modernization <strong>and</strong> Value Change 15<br />

2.2 Organizational Changes <strong>and</strong> Social Capital 21<br />

2.2.1 Organizational Changes 21<br />

2.2.2 Declining Social Capital <strong>and</strong> Elite-Challenging Activities 25<br />

2.3 Resources, Motivation <strong>and</strong> the Question of Political Equality 30<br />

2.3.1 Political Equality 30<br />

2.3.2 Resources, Equality <strong>and</strong> Elite-Challenging Activities 33<br />

2.3.3 Motivation, Equality <strong>and</strong> Elite-Challenging Activities 35<br />

2.4 Opportunity Structures <strong>and</strong> Elite-Challenging Activities 38<br />

2.5 Crisis of <strong>Democracy</strong>: Government Overload <strong>and</strong> Elite-<br />

Challenging Activities 41<br />

3 Hypotheses 44<br />

B<br />

Methods <strong>and</strong> Data<br />

4 Methodological Background, Data <strong>and</strong> Measures 50<br />

4.1 Survey Research <strong>and</strong> Alternative Ways to Measure<br />

<strong>Participation</strong> 51<br />

4.2 Country Selection 56<br />

4.3 Data Sets <strong>and</strong> Measures of Elite-Challenging Behavior 61<br />

4.4 Measurement of Elite-Challenging Political Action (dependent<br />

variable) 66

C<br />

Empirical Analyses<br />

5 “The Rise <strong>and</strong> Fall” of Elite-Challenging Political <strong>Participation</strong>?<br />

Trends <strong>and</strong> Cross-Country Differences in Elite-Challenging<br />

Activities 70<br />

5.1 Cross-Country Differences in Levels <strong>and</strong> Forms of Elite-<br />

Challenging Activities 70<br />

5.2 Trends in Elite-Challenging Activities 81<br />

6 Common Patterns of Complement or Displacement? Elite-<br />

Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Other Forms of Political Activism 89<br />

6.1 Voting 91<br />

6.2 Conventional <strong>Participation</strong> 95<br />

6.3 Civic Activism 98<br />

7 Down <strong>and</strong> Down We Go? Social Capital <strong>and</strong> Elite-Challenging<br />

Activities 107<br />

7.1 The Structural Component: Voluntary Associations <strong>and</strong><br />

Informal Networks 109<br />

7.2 The Motivational or Cultural Component: Social Trust 121<br />

7.3 Networks or Trust: Which Component of Social Capital<br />

Generates Elite-Challenging Activities? 126<br />

8 Individual Characteristics or Context Factors: What Matters for<br />

Elite-Challenging <strong>Participation</strong>? 135<br />

8.1 Elite-Challenging <strong>Participation</strong> <strong>and</strong> Individual-Level<br />

Resources <strong>and</strong> Motivation: The Question of Inequality 136<br />

8.2 Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Context Factors 143<br />

8.3 The Multilevel Model: What Determines Elite Challenging<br />

Activities? 155<br />

9 Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> <strong>Democracy</strong> 167<br />

9.1 The Societal Level: Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Democracy</strong> 167<br />

9.1.1 Measures of <strong>Democracy</strong> 168<br />

9.1.2 Measures of Elite Integrity 173<br />

9.2 The Individual Level: Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong><br />

Democratic Orientations 178

9.2.1 Support for <strong>Democracy</strong> 178<br />

9.2.2 Political Involvement 184<br />

9.2.3 Liberal Orientations 187<br />

Conclusion 194<br />

Bibliography 201<br />

Appendix 226

Figures <strong>and</strong> Tables<br />

Figure 2-1 Change in Party Membership (1980-2000, in %) 23<br />

Figure 4-1 Thresholds in Unconventional <strong>Participation</strong> 67<br />

Figure 5-1 <strong>Participation</strong> in Elite-Challenging Activities, by Country in %<br />

(pooled WVS/EVS 2000-02/2005-07) 71<br />

Figure 5-2<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities in Various Societies, in %, pooled<br />

WVS/EVS 1999-2001 <strong>and</strong> WVS 2005-07 73<br />

Figure 5-3 Elite-Challenging Activities in Various Societies, in %<br />

(WVS/EVS 1999-2002) 75<br />

Figure 5-4 Signed Petition during the past 12 Months, ESS 2004, in % 77<br />

Figure 5-5 Attended Demonstration during the past 12 Months, ESS 2004,<br />

in % 78<br />

Figure 5-6 Political Consumerism, ESS 2002, in % 80<br />

Figure 5-7<br />

Figure 5-8a<br />

Figure 5-8b<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities 1974-1999 in Six Postindustrial<br />

Democracies, in % 81<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities in Postindustrial Democracies:<br />

English-Speaking Societies <strong>and</strong> Japan, in %, WVS/EVS 81<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities in Postindustrial Democracies:<br />

Western European Societies, in %, WVS/EVS 81<br />

Figure 5-9 Elite-Challenging Activities in Ex-Communist Societies, in %,<br />

WVS/EVS 85<br />

Figure 5-10<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities in Ex-Communist Post-Soviet<br />

Societies, in %, WVS/EVS 86<br />

Figure 5-11 Elite-Challenging Activities in Other Societies, in %, WVS 87<br />

Figure 6-1 Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Voting (ESS 2002) 93<br />

Figure 6-2<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Conventional <strong>Participation</strong><br />

(ESS 2002) 96<br />

Figure 6-3 Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Activity in Interest 100

Organizations (WVS/EVS 1999-2001)<br />

Figure 6-4<br />

Figure 6-5<br />

Figure 7-1<br />

Figure 7-2<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Activity in Citizen Action<br />

Groups (WVS/EVS 1999-2001) 101<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Civic Activism in Selected<br />

Postindustrial Democracies 1981-1999 (WVS/EVS) 105<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Membership in Associations<br />

(ESS 2002) 112<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Active Membership in<br />

Associations (ESS 2002) 114<br />

Figure 7-3 Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Social Activity (ESS 2002) 115<br />

Figure 7-4<br />

Figure 7-5<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Average Membership in<br />

European Societies (ESS 2002) 116<br />

Informal Networks in European Societies <strong>and</strong> Elite-<br />

Challenging Activities (ESS 2002) 119<br />

Figure 7-6 Trust Level <strong>and</strong> Elite-Challenging Activities (ESS 2002) 123<br />

Figure 8-1<br />

Figure 8-2<br />

Figure 8-3<br />

Figure 8-4<br />

Figure 8-5<br />

Figure 8-6<br />

Figure 9-1<br />

Figure 9-2<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities (WVS 2000-2005) <strong>and</strong> Voice &<br />

Accountability 145<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities (WVS 2000-2005) <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Democracy</strong> Stock 147<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities (WVS 2000-2005) <strong>and</strong> National<br />

Affluence 148<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities (WVS 2000-2005) <strong>and</strong> Inequality<br />

in a Society 149<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities (WVS 2000-2005) <strong>and</strong><br />

Tertiarization 151<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities (WVS 2000-2005) <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Happiness Level in a Society 152<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Institutional <strong>Democracy</strong><br />

(POLITY I-IV, 2001-2004) 169<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> <strong>Democracy</strong>: Freedom House<br />

(2000-2006) 171

Figure 9-3<br />

Figure 9-4<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Perception of Corruption<br />

(Transparency International, 2001-2006) 173<br />

Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong> Control of Corruption (World<br />

Bank, 2002-2006) 175<br />

Table 3-1 Summary of Hypotheses 48<br />

Table 4-1<br />

Democratic Societies Included in the Survey Projects: Political<br />

Action Study (PA), World Values Survey/European Values<br />

Survey (WVS/EVS) <strong>and</strong> European Social Survey (ESS) 59<br />

Table 4-2 Factor Analysis for Elite-Challenging Activities 68<br />

Table 5-1 Elite-Challenging Activities, in %, ESS 2002, 2004 76<br />

Table 6-1<br />

Table 6-2<br />

Table 6-3<br />

Individual-Level Correlations between Elite-Challenging<br />

Activities <strong>and</strong> Voting (ESS 2002) 94<br />

Individual-Level Correlations between Elite-Challenging<br />

Activities <strong>and</strong> Conventional <strong>Participation</strong> (ESS 2002) 97<br />

Individual-Level Correlation between Elite-Challenging Activities<br />

<strong>and</strong> Civic Activism (WVS/EVS 1999-2001) 103<br />

Table 7-1 Factor Analyses for Measures of Informal Networks (ESS 2002) 118<br />

Table 7-2<br />

Table 7-3<br />

Individual-Level Correlation: Measures of Social Capital’s<br />

Structural Components <strong>and</strong> Elite-Challenging Activities (ESS<br />

2002) 121<br />

Individual-Level Correlation: Social Trust <strong>and</strong> Elite-Challenging<br />

Activities (ESS 2002) 125<br />

Table 7-4 Individual-Level, Binary Logistic Regression (ESS 2002) 127<br />

Table 7-5<br />

Table 8-1<br />

Multi-Level (Hierarchical Generalized Linear) Model of Social<br />

Capital <strong>and</strong> Elite-Challenging Activities (ESS 2002) 133<br />

Binary-Logistic Regression: Resources <strong>and</strong> <strong>Participation</strong> (Political<br />

Action Study 1974 <strong>and</strong> ESS 2004) 138

Table 8-2<br />

Table 8-3a<br />

Table 8-3b<br />

Binary-Logistic Regression: Resources, Motivation <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Participation</strong> (Political Action Study 1974 <strong>and</strong> ESS 2004) 141<br />

T-Test for Electoral System <strong>and</strong> Elite-Challenging Activities<br />

(WVS 2000-2005) 154<br />

T-Test for System of Governance <strong>and</strong> Elite-Challenging Activities<br />

(WVS 2000-2005) 154<br />

Table 8-4 Correlation Effects Among Level-2 Variables 157<br />

Table 8-5<br />

Table 9-1<br />

Table 9-2<br />

Table 9-3<br />

Table 9-4<br />

Table 9-5<br />

Multi-Level Model (HGLM): Individual-Level <strong>and</strong> Contextual<br />

Determinants of Elite-Challenging Activities (WVS 2000-2005) 163<br />

Zero-Order <strong>and</strong> Partial Correlation: Elite-Challenging Activities<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Democracy</strong> 177<br />

Individual-Level Correlation: Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong><br />

Support for <strong>Democracy</strong> (WVS/EVS 1999-2001) 179<br />

Individual-Level Correlation: Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong><br />

Underst<strong>and</strong>ing of <strong>Democracy</strong> (WVS/EVS 2005-07) 183<br />

Individual-Level Correlation: Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong><br />

Political Involvement (WVS/EVS 1999-2001) 186<br />

Individual-Level Correlation: Elite-Challenging Activities <strong>and</strong><br />

Liberal Orientation (WVS/EVS 1999-2001) 189<br />

Table 9-6 Binary-Logistic Regression Analysis (WVS/EVS 1999-2001)<br />

(dependent variable: Elite-Challenging Activities) 192<br />

Table C1 Results of Hypotheses Testing 196

Introduction<br />

“The effective isolation of protest to the materialist grievances of the poorer <strong>and</strong><br />

less-educated will restore unconventional politics pretty much to the position it<br />

occupied before the rise of the 1960s protest movements: largely confined to<br />

groups whose loyalty to the system is most questionable, to marginal groups,<br />

<strong>and</strong> to situationally generated protests whose rationales may be relatively<br />

difficult to identify <strong>and</strong> which are therefore always susceptible to being labeled<br />

‘irrational’. From that point it is but a short step to the progressive<br />

delegitimation of protest” (Rootes 1981: 428).<br />

When Barnes <strong>and</strong> Kaase et al. (1979) published their l<strong>and</strong>mark empirical study on the<br />

expansion of the participation repertoire in Western democracies 30 years ago, the<br />

authors faced harsh criticism by fellow scholars. The critique was mostly directed at one<br />

essential result of the comparative study: the future role of unconventional participation.<br />

In sharp contrast to the above statement, Barnes <strong>and</strong> Kaase et al. (1979) predicted a<br />

permanent change in Western societies, considering the rise in protest activism not to be<br />

a short-term, anecdotal event: “We interpret this increase in potential for protest to be a<br />

lasting characteristic of democratic mass publics <strong>and</strong> not just a sudden surge in political<br />

involvement bound to fade away as time goes by” (Kaase <strong>and</strong> Barnes 1979: 524).<br />

Ever since that study, a number of important books <strong>and</strong> essays have documented the<br />

spread <strong>and</strong> acceptance of protest activism or elite-challenging activities around the globe<br />

(Jennings <strong>and</strong> van Deth et al. 1990; Inglehart 1990; Parry, Moyser <strong>and</strong> Day 1992; Verba,<br />

Schlozman <strong>and</strong> Brady 1995; Roller <strong>and</strong> Wessels 1996; Van Aelst <strong>and</strong> Walgrave 2001;<br />

Dalton 2002; Norris 2002; Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Catterberg 2003; Dalton <strong>and</strong> van Sickle 2004;<br />

Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Welzel 2005; Norris, Walgrave <strong>and</strong> Van Aelst 2005).<br />

Along similar lines, the social movement literature has described elite-challenging<br />

activities as contentious forms of collective action (Mc Adam 1988; Jenkins <strong>and</strong><br />

Kl<strong>and</strong>ermans 1995; Kriesi et al. 1995; Tarrow 1998; Rucht, Koopmans <strong>and</strong> Neidhardt<br />

1998; Giugni, McAdam <strong>and</strong> Tilly 1999; della Porta, Kriesi <strong>and</strong> Rucht 1999; Rucht 2001;<br />

McAdam, Tarrow <strong>and</strong> Tilly 2001; Diani <strong>and</strong> McAdam 2003; Davis et al. 2005).<br />

1

Whereas the early, more qualitatively oriented research in the tradition of Charles Tilly<br />

usually focused on single movements or nations, the more recent quantitative studies on<br />

these movements are of comparative nature, although limited in their scope due to the<br />

availability of protest event data. What these studies have in common is their focus on<br />

the movement or the contentious action itself, not on the resources or motivation of the<br />

participants or the large-scale democratic consequences of an exp<strong>and</strong>ed citizen action<br />

repertoire.<br />

Today participation in demonstrations <strong>and</strong> signing petitions are far from being a tool for<br />

marginal or democracy-endangering groups of societies. At the same time, we do not<br />

only observe rising numbers of participants but also an increase in the legitimacy that<br />

people attribute to these activities (Topf 1995; Van Aelst <strong>and</strong> Walgrave 2001).<br />

According to Fuchs (1990) we have faced a “normalization of the unconventional” (see<br />

also Della Porta 1999), although it should be noted that the term “unconventional<br />

participation” has been subject to debate since the very time it was introduced by the<br />

Political Action scholars. 1 Originally, the term “unconventional” referred to that<br />

political behavior in a regime that did not match its norms of law <strong>and</strong> custom with<br />

respect to political participation (Kaase <strong>and</strong> Marsh 1979: 41). Reflecting this academic<br />

dispute, the Political Action group has admitted that the term “unconventional” was<br />

already misleading by the time when it was introduced: “Only after getting into our data<br />

did we - <strong>and</strong> most other scholars - begin to realize that most, though not all, of the<br />

protest activities that we had targeted were in fact by that time viewed as quite<br />

conventional by large numbers of people <strong>and</strong> sometimes by strong majorities of the<br />

population. What is considered normal, conventional, even acceptable forms of political<br />

behavior is thus variable” (Barnes 2004: 4; emphasis as in the original).<br />

As these activities have become more widespread <strong>and</strong> accepted as a normal, even<br />

‘conventional’ political tool by the wider publics, the term ‘unconventional’ does no<br />

longer capture the nature of these activities. Inglehart has suggested referring to these<br />

1 Since then, the appropriateness of terminology has been debated, including counter-proposals for new<br />

typologies in participation research (Uehlinger 1988).<br />

2

forms of participation as elite-challenging activities (Inglehart 1990, 1997; Inglehart <strong>and</strong><br />

Catterberg 2003; Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Welzel 2005). These activities take place outside<br />

institutionalized channels of political participation (like voting or joining a political<br />

party) <strong>and</strong> are therefore distinct from elite-directed forms of mass activities (Inglehart<br />

<strong>and</strong> Welzel 2005: 118). Elite-challenging activities are a spontaneous, short-term <strong>and</strong><br />

issue-oriented rather than long-term <strong>and</strong> permanent form of engagement. They range<br />

from participation in demonstrations such as the Belgian white march 2 in 1996 or antiwar<br />

protests around the globe in 2003, to petitioning against child labor, or to<br />

deliberately buying CFC-free products, cosmetics that were not tested on animals, or<br />

fair-trade products. As these activities confront political <strong>and</strong> other elites with dem<strong>and</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> pressure from below, “[c]itizen participation is becoming more closely linked to<br />

citizen influence” (Dalton 2000b: 929). It should be noted that the term “elite” is not<br />

referring to a group in a society that st<strong>and</strong>s out by characteristics such as social class or<br />

education but refers to people in leadership positions who regularly take part in<br />

(political) decision-making (Hoffmann-Lange 2007: 910). In this sense, it follows a<br />

broad underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the term as elites are not necessarily limited to political elites.<br />

What are the implications of the exp<strong>and</strong>ed action repertoire? Addressing this question,<br />

the thesis aims at contributing to the debate about declining civic activism (Putnam<br />

(1993, 1995a, 2000, 2002). The research question guiding this thesis is: What are the<br />

dynamics, causes (determinants) <strong>and</strong> consequences of elite-challenging activities? This<br />

question will be answered using a broad empirical database which combines information<br />

from different large-scale comparative survey projects over a period of more than 30<br />

years. The dynamic dimension refers to the expansion of the political action repertoire<br />

<strong>and</strong> is the starting point of the empirical analyses: How has participation in elitechallenging<br />

activities changed over the past decades? The descriptive part provides a<br />

first test for the robustness of the findings in other studies: Is the increase in noninstitutionalized<br />

forms occurring in all societies, or is this development restricted to<br />

2 The Belgian white march took place in the aftermath of a large case of child abuse <strong>and</strong> murder. Around<br />

300.000 people gathered in October 1996 in Brussels to demonstrate their solidarity with the victims <strong>and</strong><br />

their families <strong>and</strong> to display their anger about deficiencies in the police investigation <strong>and</strong> the judiciary<br />

system (Lippens 1998).<br />

3

Western postindustrial democracies? In addition to cross-country differences, a second<br />

emphasis is given to the relation between elite-challenging activities <strong>and</strong><br />

institutionalized forms of participation, discussing whether one goes at the expense of<br />

the other. The cause dimension examines determinants for elite-challenging activities: at<br />

the individual level as resources <strong>and</strong> motivation, <strong>and</strong> at the societal level as context<br />

factors. Political mobilization does not happen in a vacuum but is always the result of an<br />

interplay between personal characteristics <strong>and</strong> environmental factors. The two-level data<br />

structure also allows testing how the determinants on both levels are related to each<br />

other: Is participation in elite-challenging activities more driven by individual<br />

characteristics or rather by contextual factors? The consequence dimension looks at<br />

implications of elite-challenging activities, treating it no longer as a dependent but as an<br />

independent variable. Many consequences of elite-challenging activities have been<br />

claimed, most of them in an implicit way, a few explicitly. The core question here is<br />

whether elite-challenging forms of participation are overburdening the democratic<br />

system with dem<strong>and</strong>s from below, or rather call for responsive, accountable elite<br />

behavior.<br />

Contribution of the study<br />

The thesis contributes to the study of political participation in general <strong>and</strong> of noninstitutionalized<br />

participation in particular in several ways:<br />

First, it is a comparative study with a large N, going beyond classical studies that remain<br />

focused on single-nations <strong>and</strong> are dominating research on political participation (Norris<br />

2007: 643). It covers more than 90 societies on six continents that vary significantly in<br />

their political, social <strong>and</strong> economic developments. Even if studies are comparative in<br />

nature, they often only briefly touch on non-institutionalized forms of participation,<br />

examining it as one variant among many types. While those studies provide a<br />

comprehensive picture of citizen participation, they often leave little room for<br />

systematic in-depth analyses targeted at elite-challenging activities. To be sure, there is a<br />

growing literature on single forms of non-institutionalized participation, e.g. on political<br />

consumerism. These studies, however, often fall short of putting these activities in the<br />

broader research context of citizen participation <strong>and</strong> democracy. By contrast, this study<br />

4

attempts to link the different approaches by providing a systematic examination of<br />

dynamics, causes <strong>and</strong> consequences of elite-challenging activities.<br />

Second, the study looks both at determinants <strong>and</strong> consequences of elite-challenging<br />

activities. Shifting the perspective from elite-challenging activities as a dependent<br />

variable (cause dimension) to a perspective where it is treated as an independent variable<br />

(consequence dimension) allows examining the implications of these actions. This is<br />

particularly vital as several determinants-related theories actually imply consequences of<br />

elite-challenging activities that are seldom tested empirically. The focus is here on the<br />

impact of these non-institutionalized activities for democracy <strong>and</strong> for social inequality.<br />

Third, when looking at determinants <strong>and</strong> consequences of elite-challenging activities,<br />

the study combines individual level <strong>and</strong> aggregate level factors. It therefore remedies<br />

one of the well-known shortcomings of participation studies: Despite the growing action<br />

repertoire “the analysis of contextual effects remained underdeveloped” (Norris 2007:<br />

630). Moreover, the study allows for a simultaneous testing of the individual <strong>and</strong><br />

societal influences, providing more knowledge to the question whether participation in<br />

elite-challenging activities is more driven by the participant’s personal characteristics or<br />

by his/her environment.<br />

The evaluation of elite-challenging activities as a bliss or bless for the flourishing of<br />

democracy is still a contested field. Normative evaluations differ so strongly not only<br />

because the interpretations are driven by contradictory normative concepts of democracy<br />

(such as elitist versus participative). They also differ because the empirical evidence is<br />

still patchy <strong>and</strong> too fragmentary in terms of longitudinal <strong>and</strong> geographical scope <strong>and</strong><br />

levels of analyses. This is where this thesis aims to contribute to existing research:<br />

providing an encompassing overview of the determinants, dynamics, <strong>and</strong> consequences<br />

of elite-challenging in both old <strong>and</strong> new democracies, so as to come to a<br />

substantiated re-evaluation of the contradictory normative assessments of elitechallenging<br />

activities on the basis of the broadest empirical evidence possible.<br />

Structure of the thesis<br />

The structure of the thesis follows the classical composition to answer the research<br />

question outlined above. The theory part (Section A) will provide the theoretical<br />

5

framework of the study with the objective to derive testable hypotheses. The methods<br />

part (Section B) will outline the methodological principles <strong>and</strong> present the data basis for<br />

the empirical analyses. The main part of the thesis is dedicated to the empirical analyses<br />

<strong>and</strong> their discussion (Section C).<br />

In more detail, I will proceed in the following way:<br />

Section A outlines the theoretical framework of the thesis. It has three objectives: to<br />

locate elite-challenging activities in the study of political participation research; to<br />

present theoretical approaches that can explain dynamics, causes <strong>and</strong> consequences of<br />

elite-challenging activities; <strong>and</strong> to develop testable hypotheses. Chapter 1 examines how<br />

elite-challenging activities can be anchored conceptually in the context of political<br />

participation research. Chapter 2 examines five theoretical approaches to political<br />

participation with the goal to extract those relevant factors that can help to explain the<br />

dynamics, causes <strong>and</strong> consequences of elite-challenging activities: In a first step, the<br />

concept of modernization is introduced, linking socio-economic development with<br />

emancipative value change <strong>and</strong> an exp<strong>and</strong>ing participation repertoire for citizens. After<br />

that, organizational changes are in the focus <strong>and</strong> put into the broader context of social<br />

capital <strong>and</strong> participation. Special attention is given to the relationship between<br />

traditional forms of political <strong>and</strong> social participation on the one h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> elitechallenging<br />

activities on the other h<strong>and</strong>. In a third step, two different sets of individuallevel<br />

determinants are being looked at: resources <strong>and</strong> motivation. This part highlights<br />

the importance of political equality for the study of political participation. Elitechallenging<br />

activities are often considered to be more dem<strong>and</strong>ing in terms of required<br />

resources <strong>and</strong> motivation, thus contributing to a widening gap between those who can<br />

exercise political influence <strong>and</strong> those who cannot. Beyond individual-level resources<br />

<strong>and</strong> motivation, fourthly, context factors are presented, shedding light on the opportunity<br />

structures <strong>and</strong> societal resources for people to become active as well. Finally, the elitist<br />

<strong>and</strong> the participatory approach to democracy are contrasted, as the interpretation of the<br />

empirical findings – in particular with regard to the expansion of the political action<br />

repertoire – yield different results. Based on these theoretical approaches, Chapter 3<br />

summarizes the testable hypotheses.<br />

6

Section B then outlines the methodological basis of the study <strong>and</strong> introduces the data<br />

sets <strong>and</strong> measures (Chapter 4). The study applies a comparative perspective <strong>and</strong> uses<br />

survey data from longitudinal representative large-scale survey projects to measure<br />

participation in elite-challenging activities: the Political Action Study (1974), the World<br />

Values Surveys/European Values Surveys (1981-2005), <strong>and</strong> the European Social Survey<br />

(2002-2004). It includes more than 90 societies on six continents, thereby covering not<br />

only the majority of the world population, but also a great variety of economic, social<br />

<strong>and</strong> political environments. There is a limitation to this most different cases design: In<br />

order to assure that political participation – in particular in elite-challenging activities –<br />

is meaningful, case selection (beyond data availability) is guided by an external<br />

assessment of a country’s compliance with political rights <strong>and</strong> civil liberties. Finally, the<br />

measurement of the dependent variable (participation in elite-challenging activities) is<br />

introduced.<br />

Section C presents the empirical analyses – the testing of the hypotheses developed at<br />

the end of the theory section <strong>and</strong> the discussion of the results. The empirical part is<br />

organized as follows: Chapter 5 (“The ‘rise <strong>and</strong> fall’ of elite-challenging participation?”)<br />

provides a first descriptive data overview for succeeding empirical analyses. Covering<br />

more than 70 societies over a period of more than 25 years, it looks at trends <strong>and</strong> crosscountry<br />

differences in levels <strong>and</strong> forms of elite-challenging activities. A first overview<br />

suggests major differences in elite-challenging activities, with participation levels from<br />

as low as 10 percent in Jordan to up to more than 80 percent in Sweden. On average, at<br />

least twice as many people in high-income societies use petitions, demonstrations <strong>and</strong><br />

boycotts than in other societies. An inspection of the ESS data also shows a significant<br />

discrepancy between Western <strong>and</strong> Eastern Europe, the latter facing a “post-honeymoon”<br />

decline of civic action (Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Catterberg 2003).<br />

Chapter 6 (“Common patterns of complement or displacement?”) looks at the<br />

relationship between elite-challenging activities <strong>and</strong> other forms of political<br />

participation such as voting, conventional participation, or participation in interest<br />

organizations <strong>and</strong> citizen action groups. It addresses the question whether elitechallenging<br />

activities are going at the expense of more traditional forms of participation,<br />

7

or whether civic activism in general is even in decline, as some scholars suggest<br />

(Putnam <strong>and</strong> Goss 2002). The empirical results do not support any of the two<br />

propositions. Chapter 7 extends the analysis to the social capital debate, providing<br />

evidence that participation in elite-challenging activities can be understood as an<br />

outcome of prevailing social capital at the societal level <strong>and</strong> as an individual resource.<br />

Taking up the discussion about the role of resources as determinants of elite-challenging<br />

activities, Chapter 8 (“What matters for elite-challenging participation?”) asks which<br />

determinants have a greater impact on participation in elite-challenging activities:<br />

individual characteristics or context factors? The final empirical chapter (Chapter 9)<br />

considers participation in elite-challenging activities no longer as a dependent but as an<br />

independent variable. It examines the linkage between these forms of participation <strong>and</strong><br />

democracy on two levels: pro-democratic orientations at the individual level, <strong>and</strong> quality<br />

of democracy <strong>and</strong> elite compliance at the aggregate level.<br />

Finally, the conclusion summarizes the findings <strong>and</strong> discusses implications of the results<br />

for future research of citizen participation in today’s representative democracies.<br />

8

A<br />

THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS<br />

The theoretical framework has three aims. First, the question should be answered how<br />

elite-challenging activities can be anchored in the context of political participation<br />

research. A summarizing overview about the participation concept will be given,<br />

followed by a discussion about the challenges that these new action forms pose to the<br />

traditional concept. In a second step, theories on political participation are examined<br />

with the goal to extract those relevant factors that can help to explain the dynamics,<br />

causes <strong>and</strong> consequences of elite-challenging activities. Finally, testable hypotheses are<br />

derived from the theoretical approaches <strong>and</strong> summarized in a concluding chapter.<br />

1. Elite-Challenging Activities as Political <strong>Participation</strong><br />

Definitions of political participation that can be found in the literature are numerous, <strong>and</strong><br />

philosophers <strong>and</strong> social scientists have early pointed to the importance of participation<br />

for democracy. Aristotle, for example, argued that man is by nature a political animal<br />

(Kraut 2002: 95) <strong>and</strong> that participation together with others in shared activities is closely<br />

linked with having a good <strong>and</strong> happy life. Pericles stressed that a citizen without an<br />

interest in public affairs is a useless character (quoted in Popper 2002: 199). Although<br />

scholars ever since have argued about how much participation of what kind is needed<br />

<strong>and</strong> desirable in a democracy, there is little disagreement that political participation – in<br />

particular the right to vote in free <strong>and</strong> fair elections – is included in most definitions <strong>and</strong><br />

measurements of democracy, most prominently coined in Dahl’s constituting elements<br />

of polyarchy: competition <strong>and</strong> participation (Dahl 1971). In a nutshell, “any book about<br />

political participation is also a book about democracy” (Parry, Moyser <strong>and</strong> Day 1992:<br />

3), with democratic legitimacy being the link between the two.<br />

Broadly speaking, political participation is defined as “the opportunity for large numbers<br />

of citizens to engage in politics” (Abramson 1995: 913), referring to “those action of<br />

private citizens by which they seek to influence or to support government <strong>and</strong> politics”<br />

(Milbrath <strong>and</strong> Goel 1977: 2). More concretely, it encompasses “those legal activities by<br />

9

private citizens that are more less directly aimed at influencing the selection of<br />

governmental personnel <strong>and</strong>/or the actions they take” (Verba, Nie <strong>and</strong> Kim 1978: 46).<br />

Brady (1999: 737) summarizes four defining aspects of political participation: its<br />

reference to ordinary citizens as actors; the action component; the political nature of<br />

activity; <strong>and</strong> the instrumental aspect of attempting to influence politics.<br />

In addition, a fifth aspects should be highlighted – the voluntary element of<br />

participation. The authors of the Political Action Study explicitly refer to political<br />

participation as “all voluntary activities by individual citizens intended to influence<br />

either directly or indirectly political choices at various levels of the political system”<br />

(Kaase <strong>and</strong> Marsh 1979: 42).<br />

With the expansion of the political action repertoire to non-institutionalized forms of<br />

citizen activism the question arises whether this narrow definition of political<br />

participation is still adequate – in particular, as these activities share characteristics<br />

uncommon to forms of traditional participation:<br />

New targets<br />

The definition of political participation provided by Verba, Nie <strong>and</strong> Kim (1978) focuses<br />

on the specific target of participation: the governmental personnel. Traditionally,<br />

participation studies have focused on institutionalized channels of participation linked to<br />

the electoral process, national or local government <strong>and</strong> parties (Norris 2007: 638).<br />

Today, the addressee of citizens activities are often found outside political institutions,<br />

such as non-governmental organization or multinational corporations. For example,<br />

ordinary citizens articulate their concerns through various forms of political<br />

consumerism where the market is used as a political arena – with the goal to change<br />

market practices (Stolle <strong>and</strong> Micheletti 2005). This can either be done in its positive<br />

form by buying fair trade products in a supermarket, in its negative form by boycotting<br />

clothing produced in sweatshops, or by engaging in discourses about market practices.<br />

These new targets of the exp<strong>and</strong>ed action repertoire also show the declining importance<br />

of the nation state. Often, governmental elites at the national level are bypassed by<br />

citizens’ activities, <strong>and</strong> multinational corporations or international political organizations<br />

are targeted directly (Norris 2002: 193). Reasons can be manifold, either because<br />

10

citizens think that national governments <strong>and</strong> legislatures are not able (or willing) to<br />

change the legislative framework accordingly, or because they consider a direct<br />

targeting to be the most effective approach. Importantly, citizens “aim at targets<br />

regardless of whether they represent public or private institutions, the importance is that<br />

they have de facto political power” (Stolle <strong>and</strong> Hooghe 2005: 5). This is also the reason<br />

why these elite-challenging activities are not necessarily “state-challenging” or<br />

“institution-challenging”, as the targets are no longer to be found only among state<br />

actors or institutions. Any study on political participation that fails to include these new<br />

targets, will leave major new forms of mass activities unconsidered.<br />

New issues: Political or non-political participation?<br />

The past decades have not only brought new targets but also new topics on the agenda,<br />

blurring the distinction between political <strong>and</strong> nonpolitical activities as well as between<br />

political <strong>and</strong> social forms of participation. These new issues are closely linked to the<br />

expansion of the action repertoire for citizens. In particular younger generations have<br />

been found to engage in sporadic <strong>and</strong> issue-oriented forms outside hierarchical networks<br />

– rather than long-term commitment in a centralized mass organization that deal with<br />

governmental affairs.<br />

Among others, these new issues have been labeled lifestyle politics (Bennett 1998). Its<br />

main characteristic is a connection between activity <strong>and</strong> self-identity: “With each<br />

lifestyle there is a corresponding life story, in the sense that by creating this specific<br />

unity of practices the actor expresses who he or she wants to be” (Spaargaren <strong>and</strong> van<br />

Vliet 2000: 55). In fact, issues that have been characterized as lifestyle topics – such as<br />

environmental protection or health <strong>and</strong> child care issues – are not new per se. “However,<br />

the intensely personal way in which they are framed is more recent” (Bennett 1998:<br />

759), such as the discussion about abortion rights in the context of freedom of personal<br />

choice. Along similar lines, the emergence of identity politics, in particular since the rise<br />

of the New Social Movements in the 1980ies, has blurred the distinction between what<br />

is political <strong>and</strong> what is private even further, exemplified in Carol Hanisch’s famous<br />

phrase “the personal is the political” (1969). Postmaterialist or emancipative values such<br />

as gender equality or ethnicity are always related to personal identities, but the fact that<br />

11

they are not related to traditional areas of state activity (such as providing existential<br />

security) does not make them less political in their scope. “Because personal identity is<br />

replacing collective identity as the basis for contemporary political engagement, the<br />

character of politics itself is changing” (Bennett 1998: 755). Thus, an exclusive focus on<br />

traditional forms might underestimate how marginalized groups in a society – such as<br />

women, in particular housewives – are a politically active part of society (Stolle <strong>and</strong><br />

Micheletti 2005: 3).<br />

In addition to the emergence of identity politics, there is another reason why the<br />

traditional distinction between political <strong>and</strong> nonpolitical activities does no longer hold.<br />

The long period of economic growth <strong>and</strong> stability <strong>and</strong> the expansion of the welfare state<br />

over the past decades have led to growing state interventions <strong>and</strong> a politicization of<br />

other spheres: “The result is that democratic government in advanced industrial societies<br />

increasingly occupies a substantial part of the national product <strong>and</strong> is a party to such<br />

divergent aspects of social life as housing, education, transportation, social security,<br />

foreign trade, <strong>and</strong> health care” (van Deth 2001: 9). Due to the growth of the public<br />

sector over the past decades, more people than ever are affected by decisions about<br />

government spending, <strong>and</strong> politics is difficult to avoid. As a consequence, the dividing<br />

line between the political <strong>and</strong> the social sphere dissolves; the same applies to the<br />

distinction between what is public <strong>and</strong> what is private.<br />

New network structures <strong>and</strong> mobilization tactics<br />

Participants of elite-challenging activities are mainly organized in horizontal, less<br />

permanent <strong>and</strong> more flexible networks. Also the forms of mobilization follow a different<br />

logic than in permanent organizations such as political parties or interest groups. As<br />

elite-challenging actions are often less planned ahead, mobilization processes can be<br />

rather spontaneous <strong>and</strong> irregular. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, forms of political consumerism are<br />

often implemented into people’s daily consumption activities (Shah et al. 2007), “hoping<br />

that my choice, in concert with others, might influence public policy” (Sapiro 2000: 11).<br />

Accordingly, new channels of mobilization provide the means to get people involved:<br />

Electronic forms of communication such as internet websites or electronic newsletters<br />

are used to coordinate action; in Spain, one day after the bomb attack in Madrid in 2004,<br />

12

citizens used SMS to keep informed <strong>and</strong> mobilize each other into what later became the<br />

largest mass demonstration in Spanish history. Online or email campaigns themselves<br />

have developed into new forms of action. Clearly, these activities <strong>and</strong> the way they are<br />

coordinated do not follow the logic of regular face-to-face meetings known from<br />

voluntary organizations. As a consequence, there exists an easy exit option for<br />

participants (Stolle <strong>and</strong> Hooghe 2005: 5), which contributes to the ad-hoc <strong>and</strong> sporadic<br />

character of these activities.<br />

New forms of action: Individual acts <strong>and</strong> collective outcomes<br />

It is obvious that any form of political participation, including elite-challenging actions,<br />

needs many to achieve an effect (Sapiro 2000:11). These new activities are collective in<br />

their effects as well. The difference, however, is that the participation act itself is a more<br />

individualized form of political action. Examples are forwarding emails, buy-cotting a<br />

certain product in the supermarket or signing a petition. It is clear, however, that all<br />

these activities, though individual in nature, still need an opportunity structure <strong>and</strong> the<br />

coordination of the activities in order to be successful. “This leads to a paradox: while<br />

these forms of protest <strong>and</strong> participation can often be seen as examples of coordinated<br />

collective action, most participants simply performs such acts alone, at home before a<br />

computer screen or in a supermarket” (Stolle <strong>and</strong> Hooghe 2005: 6).<br />

In the past decades we could observe a change in the political action repertoire. The<br />

expansion towards elite-challenging activities such as demonstrations, petitions or<br />

political consumerism has posed the question whether <strong>and</strong> how these activities fit into<br />

the definition of political participation. Some have even claimed that we are running into<br />

the danger of a “broad theory of everything” when exp<strong>and</strong>ing the concept of political<br />

participation to all these new action forms (van Deth 2001). However, a conception of<br />

political participation that focuses too narrowly on traditional forms, targets <strong>and</strong> issues<br />

falls into the trap of falling behind reality <strong>and</strong> ignoring innovations, thus<br />

underestimating the interest <strong>and</strong> willingness of citizens around the world to be<br />

politically engaged. It also has important consequences for the way possible<br />

implications of elite-challenging activities are interpreted.<br />

13

In fact, the “Political Action Study” was the first systematic empirical study that<br />

challenged the – up to this point dominant – view among scholars <strong>and</strong> politicians that<br />

protest activism happened to be a threat to the democratic political order, even<br />

contributing to a “crisis of democracy” (Huntington 1968, 1974a, b; Croizier,<br />

Huntington <strong>and</strong> Watanuki 1975). Later on I will elaborate in more detail on the debated<br />

consequences of the “participatory revolution” (Kaase 1984) that has taken place in<br />

postindustrial democracies.<br />

To be sure, people gathering to voice their opinion, infuriated workers on strike, or any<br />

other form of disobedience, even collective violence, is surely not exclusively a<br />

characteristic of our time (Gurr 1970; Tilly, Tilly <strong>and</strong> Tilly 1975; Graham <strong>and</strong> Gurr<br />

1979; Dalton 2002: 58-60). However, violent forms of protest activism have been <strong>and</strong><br />

still are a marginal phenomenon in all postindustrial societies. Whereas also the<br />

acceptance to use violent means to support a political opinion is still very low,<br />

acceptance <strong>and</strong> exercise of non-violent elite-challenging activities have gained<br />

widespread popular support. The political action repertoire has exp<strong>and</strong>ed during the past<br />

decades as societies have undergone tremendous political, economic <strong>and</strong> social changes,<br />

summarized in the account of modernization theory. The following chapter will present<br />

different theoretical approaches to explain the dynamics, causes <strong>and</strong> consequences of<br />

elite-challenging activities.<br />

14

2. Theoretical Framework: What Explains <strong>Dynamics</strong>, <strong>Causes</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

Consequences of Elite-Challenging Activities?<br />

2.1 Modernization <strong>and</strong> Value Change<br />

Mostly linked with processes of democratization as their general outcome, theories of<br />

modernization also provide one of the predominant explanations for long-term<br />

developments in political participation (Norris 2002: 19). The cultural variant of<br />

modernization theory links socio-economic development to value change – in particular<br />

change in authority relations – to an expansion of the participation repertoire, allowing<br />

for propositions on all three dimensions of analysis: the dynamics, determinants <strong>and</strong><br />

consequences of elite-challenging activities.<br />

Despite its broad variety of meanings (Schmidt 2001: 9961-9963), the term<br />

“modernization” usually refers to a transformation process from a traditional, rural,<br />

agrarian society to a secular, urban <strong>and</strong> industrial society (Inglehart 2001: 9965-9971).<br />

This process is accompanied by profound economic, cultural <strong>and</strong> political changes that<br />

result in a deep societal reorganization which, in turn, affects the conditions for mass<br />

participation. Most importantly, modernization theory claims that the economic <strong>and</strong><br />

social circumstances leave an imprint on the people exposed to them, affecting people’s<br />

opportunities, their resources <strong>and</strong> what people think about <strong>and</strong> want out of life.<br />

“Socioeconomic development brings roughly predictable cultural changes” (Inglehart<br />

<strong>and</strong> Welzel 2005: 15) because with changing external conditions, experiences <strong>and</strong><br />

opportunities, people’s values tend to change into a similar direction. Obviously,<br />

adherents of this approach attribute a certain outcome to the modernization process –<br />

although scholars have argued extensively about the deterministic or probabilistic<br />

character of this relationship.<br />

In general, modernization is considered to be “one of the two giant leaps forward that<br />

have transformed the human condition” (Inglehart 2001: 9966). The agrarian revolution<br />

that marked the transition from hunting <strong>and</strong> gathering societies to agrarian societies is<br />

deemed as the first fundamental cut in societal development. One could debate which of<br />

these two crucial developments has been more fundamental in its scope of changing<br />

existing societies. Interestingly, they have been equally successful if one considers<br />

15

productivity <strong>and</strong> the possibility to provide people with food - in the course of both<br />

revolutions those capacities have been raised by a hundredfold. But considering the time<br />

span available for the changes to take place, a tremendous difference becomes apparent:<br />

“[W]hile it took thous<strong>and</strong>s of years for the discovery of agriculture to transform the<br />

world, the industrial revolution spread throughout the world in only two centuries”<br />

(Inglehart 2001: 9966).<br />

Since the 1950ies, numerous debates about economic, social <strong>and</strong> political consequences<br />

of modernization were stimulated in the social science community, even though<br />

modernization theory was also then not a new phenomenon. Nevertheless, it did not<br />

enjoy a broad scope of academic interest before the 1950ies <strong>and</strong> 60ies 3 , about 90 years<br />

after Karl Marx had published his influential pieces of work, anticipating the societal<br />

effects of economic growth (Marx 1990 [1867]; 1993 [1858]). Based on this work,<br />

subsequent scholars have argued that modernization theory rests upon the assumption<br />

that societal changes follow – to a certain degree – predictable pathways, meaning that<br />

particular developments are inevitable for such a society, simply because they are<br />

inherent to the process of modernization. Among those ‘side effects’, secularization,<br />

bureaucratization <strong>and</strong> individualization play a significant role but the economic process<br />

of industrialization is at the core of modernization (Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Baker 2000: 20;<br />

Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Welzel 2005).<br />

Lipset (1959, 1981 [1960], 1992, 1994; see also Lipset, Seong <strong>and</strong> Torres 1993) is one<br />

of the most prominent proponents of this approach. Analyzing pathways to modernity in<br />

Britain, the US <strong>and</strong> Western Europe during the 19 th century, he could show that modern<br />

societies developed at the same time when these societies transformed into capitalist<br />

ones. Lipset was not the only one noting a relationship between market economy <strong>and</strong><br />

democracy (see, for example, Schumpeter 1950; Moore 1966; Diamond 1992; Diamond,<br />

Linz <strong>and</strong> Lipset 1988) but his résumé of what he considered to be a causal relationship<br />

3 With the emerging broad interest in modernization, Rustow noted a trend of changing paradigms from an<br />

institutional-legal to a behavioral-cultural approach within the discipline. This trend is also reflected in a<br />

wider acknowledgement of sociological, anthropological as well as psychological concepts among<br />

political scientists (Rustow 1968: 37-38).<br />

16

has impacted generations of academic scholars: “The more well-to-do a nation, the<br />

greater the chances that it will sustain democracies” (Lipset 1960: 48). 4<br />

Considering the eminent consequences of modernization, Lipset also acknowledged<br />

Marx’ prediction with regard to the relationship between capitalism <strong>and</strong> societal<br />

changes. His failures, among others his prediction about a proletarian revolution, are<br />

well known, but Marx (1990 [1867]; 1993 [1858]) succeeded in identifying very early<br />

the specific political <strong>and</strong> social consequences of a society’s development towards<br />

capitalism. And even though workers did not become the ruling class, they have been<br />

the ones strongly <strong>and</strong> successfully pushing for exp<strong>and</strong>ing universal suffrage <strong>and</strong> the<br />

rights of political parties (Rueschemeyer, Stephens <strong>and</strong> Stephens 1992). This line of<br />

argument also follows assumptions according to which modernization brings along<br />

social mobilization <strong>and</strong>, in the end, mass participation (Deutsch 1961).<br />

In contrast to the designated role that Marx earmarked for the working class, Lipset<br />

attributed a special role in pushing for democratization to the middle class of a society.<br />

For Lipset, democracy was a direct outcome of capitalism. Looking at the history of<br />

today’s representative democracies, his argument finds support in the fact that<br />

democratic societies have almost exclusively occurred in modern capitalist societies. In<br />

the past, this supposition (<strong>and</strong> the linear interpretation of the relationship between<br />

socioeconomic factors <strong>and</strong> democracy) has (mis)led some scholars to present<br />

“guidelines for democratizers” (Huntington 1991) – practical advice <strong>and</strong> instructions on<br />

how to create democracy. Duly applied, so the impression, it works like a recipe for a<br />

good lunch menu.<br />

During the last years, non-linear approaches to modernization have come to the fore of<br />

social science research. Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Welzel (2005: 25), for example, have followed<br />

Bell (1973) in his differentiation between two distinct phases of modernization:<br />

industrialization <strong>and</strong> postindustrialization. Both phases differ significantly in the way<br />

4 To illustrate the importance of Lipset’s research: His 1959 article ranks amongst the all-time top-ten<br />

citations of the discipline’s top journal, the American Political Science Review (Siegelman 2006).<br />

“Excluding Duverger’s law on the effect of single-member districts on party systems, it may be the<br />

strongest empirical generalization we have in comparative politics to date” Boix (2003: 1-2).<br />

17

they affect societies: Whereas industrialization is accompanied by bureaucratization,<br />

centralization, rationalization <strong>and</strong> secularization, postindustrial societies show an<br />

increasing emphasis on autonomy, choice, creativity <strong>and</strong> self-expression. At the same<br />

time, both processes have changed the way people relate to authorities. Nevertheless, the<br />

authors acknowledge that cultures, even when they are exposed to the same (changing)<br />

conditions, remain relatively persistent, rejecting the notion of converging value<br />

patterns. So, societies are changing, <strong>and</strong> they change into similar directions – but the<br />

differences between these societies largely remain the same (Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Welzel 2005:<br />

19-20).<br />

Technological innovations have been at the heart of the first modernization process, <strong>and</strong><br />

they had enormous implications. Before industrialization, “the vast majority made its<br />

living from agriculture <strong>and</strong> depended on things that came from heaven, like the sun <strong>and</strong><br />

rain” (Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Welzel 2005: 26). When people gained, for the first time, control<br />

over the natural environment, this also meant challenging the authority of the church:<br />

“Praying to God for good harvest was no longer necessary when one could depend on<br />

fertilizer <strong>and</strong> insecticides” (ibid.). So, industrialization brought a secularization of<br />

authority, shifting the source of authority from religion to more secular ideologies.<br />

However, these societies were still characterized by pronounced authority relations <strong>and</strong><br />

socioeconomic conditions that are shaped by the disciplined, st<strong>and</strong>ardized <strong>and</strong> uniform<br />

mode of industrial production.<br />

Emancipation from authority takes place only during the postindustrialization phase,<br />

when the focus shifts from external authority to more individual autonomy <strong>and</strong> human<br />

choice (Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Baker 2000; Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Welzel 2005). Economically,<br />

postindustrial societies are characterized by a shift of the major workforce from the<br />

industrial to the service sector. Working in service-oriented professions requires<br />

different skills than working at the production line, for example to fast process<br />

information, to make autonomous decisions or to propose creative ideas. “Service <strong>and</strong><br />

knowledge workers deal with people <strong>and</strong> concepts, operating in a world where<br />

innovation <strong>and</strong> the freedom to exercise individual judgements are essential. Creativity,<br />

imagination, <strong>and</strong> intellectual independence become central” (Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Welzel 2005:<br />

18

28-29). The experience of these activities does not leave people’s value orientations<br />

unaltered, shifting priorities from survival to self-expression values.<br />

As Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Welzel (2005: 28-29) have argued, postindustrial societies differ from<br />

industrial societies in three major aspects. First, postindustrial societies like the ones in<br />

Western Europe or the USA after World War II have experienced an unprecedented<br />

phase of peace, security <strong>and</strong> economic prosperity. As people tend to pursue goals that<br />

are short in supply (Inglehart 1977: 22), <strong>and</strong> as they strive for higher goals once material<br />

goals (like physical <strong>and</strong> economic security) are accomplished, people tend to put<br />

stronger emphasis on self-actualization Maslow (1954). 5<br />

Second, as tasks in the service sector tend to be cognitively more dem<strong>and</strong>ing than<br />

previous activities, broad access to higher education becomes a necessary condition for<br />

societies to become (or stay) competitive. Postindustrial societies are therefore<br />

characterized by higher levels of formal education. At the same time, this cognitive<br />

mobilization leaves an imprint on people’s belief systems. “Thus, rising levels of<br />

education, increasing cognitive <strong>and</strong> informational requirements in economic activities,<br />

<strong>and</strong> increasing proliferation of knowledge via mass media make people intellectually<br />

more independent, diminishing cognitive constraints on human choice” (Inglehart <strong>and</strong><br />

Welzel 2005: 29).<br />

Third, as their daily work activities become more independent <strong>and</strong> dest<strong>and</strong>ardized,<br />

people dem<strong>and</strong> the same kind of independence, choice <strong>and</strong> creative power in other areas<br />

of their lives. The expansion of the welfare state has contributed to the realization of<br />

these dem<strong>and</strong>s, protecting the individual against certain risks that previously have been<br />

covered by close group ties. Today, the belonging to a group, be it the family or the<br />

church, is no longer a question of survival but of choice (Beck 2002). Families <strong>and</strong> other<br />

group affiliations are changing “from a community of need to elective affinities” (Beck-<br />

Gernsheim 1998).<br />

All three processes show how people change their values as a response to the conditions<br />

that surround them. Given the favorable circumstances described above, all three<br />

5 Inglehart (1977, 1990) has referred to Maslow’s values of self-actualization as postmaterialistic values,<br />

emphasizing nonphysiological needs such as (self) esteem, self-enhancement <strong>and</strong> aesthetic satisfaction.<br />

Opposed to that are materialistic values, fulfilling material or physiological needs such as survival <strong>and</strong><br />

security.<br />

19

contribute to a change in people’s value priorities, shifting the emphasis from survival to<br />

self-expression values. As people acquire most of their basic value priorities in their<br />

formative years, that is during childhood <strong>and</strong> adolescence, it has been argued that value<br />

change can only proceed as an intergenerational process (Inglehart 1977: 23, 1990: 33).<br />

As political, social <strong>and</strong> economic conditions are changing as a consequence of<br />

postindustrialization, younger generations adapt to these circumstances <strong>and</strong> internalize<br />

postmaterialistic or self-expression values (Inglehart 1990: 136; Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Welzel<br />

2005: 100-105).<br />

These changing value priorities as consequences of societal modernization have had<br />

important implications for political participation. Industrialization <strong>and</strong> the shifting<br />

emphasis towards secular-rational values, on the one h<strong>and</strong>, opened, for the first time in<br />

human history, the door for mass participation, promoting not only universal suffrage<br />

but also mass organizations to represent interests of people, even majorities, who had so<br />

far been excluded from any kind of political participation <strong>and</strong> interest representation. As<br />

such, catch-all parties (like socialist parties as mass organizations for workers’ interests)<br />

emerged (Kirchheimer 1965), <strong>and</strong> most of the parties that were formed as a response to<br />

deeply rooted societal conflicts of that time still shape the structure of today’s Western<br />

European party systems (Lipset <strong>and</strong> Rokkan 1967; Rokkan 2000).<br />

While industrialization brought unprecedented levels of inclusion <strong>and</strong> political<br />

participation, the consequences of postindustrialization are less straightforward since<br />

these social changes tend to produce “cross-cutting developments, some of which could<br />

possibly depress activism, while others seem likely to encourage civic engagement”<br />

(Norris 2002: 23). Postindustrialization produces a citizenry that is better educated, more<br />

skilled <strong>and</strong> more informed than ever before. Generally, they also have more leisure time,<br />

<strong>and</strong> through the expansion <strong>and</strong> diversification of the media system (e.g. internet),<br />

information <strong>and</strong> knowledge is easier accessible. Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Welzel (2005) now argue<br />

that the value change from survival to self-expression values brings about greater<br />

skepticism towards all kinds of authorities, including political authorities (see also<br />

Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Catterberg 2003: 79). As these authority relations become weaker, people<br />

tend to question political elites, to become more critical <strong>and</strong> less inclined to participate<br />

20

in mass-based, hierarchical organizations that could not function without the discipline<br />

<strong>and</strong> ordination of its members.<br />

The cultural variant of modernization theory leads to a number of hypotheses about the<br />

dynamics, causes <strong>and</strong> consequences of elite-challenging activities.<br />

On the individual level, younger citizens <strong>and</strong> those with higher emancipative values are<br />

more actively participating in demonstrations, petitions <strong>and</strong> political consumerism. This<br />

hypothesis refers to the cause dimension.<br />

On the aggregate level, three propositions can be derived. First, as a consequence of<br />

progressing postindustrialization, an increase in the overall level of elite-challenging<br />

activities can be observed. This hypothesis refers to the dynamics dimension. Second,<br />

societies with higher socioeconomic development show higher levels of elitechallenging<br />

activities (cause dimension). Third, as elite-challenging activities push for<br />

responsible <strong>and</strong> transparent elite behavior, thus limiting the abuse of entrusted power,<br />

the quality of democracy improves with higher levels of elite-challenging activities. This<br />

refers to the consequence dimension of elite-challenging participation.<br />

As individualization affects several areas of their life, people are today less ready to<br />

show a long-term commitment to any kind of organization. Rather, they prefer to<br />

become politically involved in more short-term, issue-oriented <strong>and</strong> expressive forms of<br />

political participation – forms that are rather elite-challenging than elite-directed<br />

(Inglehart <strong>and</strong> Welzel 2005: 118). This has important consequences for traditional<br />

organizations.<br />

2.2 Organizational Changes <strong>and</strong> Social Capital<br />

2.2.1 Organizational changes<br />

Most visibly, this change has affected political parties. Repeatedly <strong>and</strong> almost<br />

unanimously, political parties have been characterized as an integral part of modern<br />

representative democracies (Schattschneider 1942; Sartori 1976). The complexity of<br />

their various activities (interest aggregation, articulation <strong>and</strong> representation; political<br />

21

education <strong>and</strong> information; elite recruitment; program development, to name only a few)<br />

has led scholars to argue that modern democracy without political parties was<br />

“unthinkable” (Schattschneider 1942: 1; see also Dalton <strong>and</strong> Wattenberg 2000a).<br />

Recent literature on party politics, however, is more characterized by a depiction of<br />

crisis than of enthusiasm: “Today, mounting evidence points to a declining role for<br />

political parties in shaping the politics of advanced industrial democracies” (Dalton <strong>and</strong><br />

Wattenberg 2000a: 3). Summarizing a multitude of simultaneous processes, this trend of<br />

decreasing importance of political parties has been described as “partisan dealignment”<br />

(Dalton 1984; Dalton, Flanagan <strong>and</strong> Beck 1984; Schmitt <strong>and</strong> Holmberg 1995; Dalton<br />

2000). Processes of individualization are the driving force behind this development<br />

where organizational changes <strong>and</strong> the rise of elite-challenging activities are often seen as<br />

two sides of the same coin. This has important <strong>and</strong> multifaceted consequences for<br />

representative democracies, ranging from questions of political socialization <strong>and</strong> civic<br />

disengagement to questions of social coherence <strong>and</strong> political accountability. But what do<br />

organizational changes mean?<br />

For one, the decreasing importance of ‘old’ mobilizing institutions such as political<br />

parties (but also labor unions, churches, <strong>and</strong> alike) is mirrored in a shrinking basis of<br />

support, suggesting that the linkage between citizens <strong>and</strong> political parties has weakened.<br />

First empirical evidence for this comes from inspecting time-series data on party<br />

membership:<br />

22

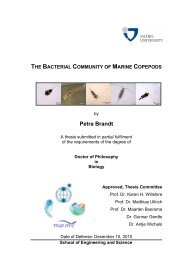

Figure 2-1: Change in Party Membership (1980 – 2000, in %) *<br />

Spain<br />

Greece<br />

Portugal<br />

Germany<br />

Belgium<br />

Irel<strong>and</strong><br />

Denmark<br />

Sweden<br />

Switzerl<strong>and</strong><br />

Austria<br />

Netherl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

Finl<strong>and</strong><br />

Norway<br />

US<br />

Italy<br />

France<br />

-100 -50 0 50 100 150 200<br />

* Source: Numbers taken from Mair <strong>and</strong> van Biezen (2001: 12).<br />

Time frame: Spain (1980-2000), Greece (1980-1998), Portugal (1980-2000), Germany (1980-1999), Belgium (1980-<br />

1999), Irel<strong>and</strong> (1980-1998), Denmark (1980-1998), Sweden (1980-1998), Switzerl<strong>and</strong> (1977-1997), Austria (1980-1999),<br />

Netherl<strong>and</strong>s (1980-2000), Finl<strong>and</strong> (1980-1998), Norway (1980-1997), United States (1980-1998), Italy (1980-1998),<br />

France (1979-1998).<br />