Dissertation_Paula Aleksandrowicz_12 ... - Jacobs University

Dissertation_Paula Aleksandrowicz_12 ... - Jacobs University Dissertation_Paula Aleksandrowicz_12 ... - Jacobs University

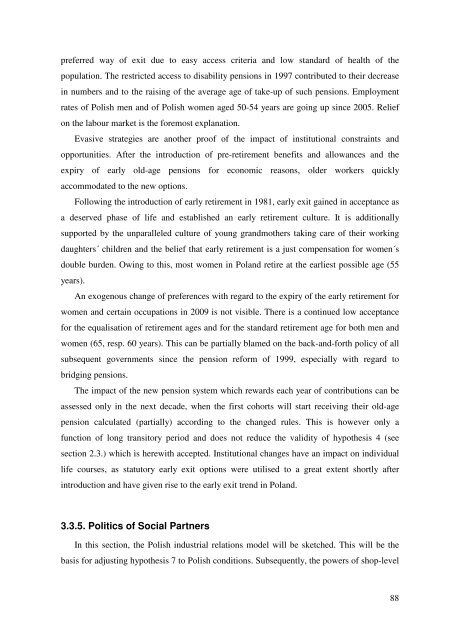

sexes 29 favoured the age of 55 as retirement age for women , and the age of 60 as retirement age for men in all waves of the survey (CBOS 2007: 4; Table 9). Table 9: Optimum retirement age for women in the opinion of Polish respondents, 1999-2007 Survey in Oct. 1999 Survey in April 2002 Survey in Dec. 2003 Survey in Dec. 2005 55 years or earlier 85% 52% 70% 67% 72% 60 years 12% 31% 22% 28% 21% 65 years 1% 9% 3% 2% 4% Above 65 years 1% 0 0 0 0 Difficult to tell 1% 8% 5% 3% 3% Source: CBOS (2007: 4). Survey in Sept. 2007 The acceptance of the lowest possible retirement age for women has decreased and the acceptance of a retirement at 60 has increased when compared to the situation in 1999. The all-time high in the acceptance of a higher retirement age for women and for men was recorded in 2002. This was probably a reverberation of the debate on retirement ages and pension adequacy that had accompanied the grand pension reform of 1999. The lower retirement age for women is regarded as a just compensation for the double or triple burden of gainful employment-household labour-child care, and as an option to take on grandmotherly duties (OBOP 1999). I will now sum up the section on aggregate results of institutional and structural changes. Just as in Germany, the pension system in Poland was used for solving labour market problems. The difference lies in the intentions – while the easing of the strain on the labour market was a side effect of policies introduced for other reasons (Ebbinghaus 2002: 163, 179), in Poland it was intentional socio-economic policy which has distorted the relations of the number of economically active to economically passive persons (Kabaj 2003: 46-48). The inflow rates into pre-retirement benefits, disability pensions and early old-age pensions picture both new institutional opportunities and the rising unemployment. Waves of unemployment swept many persons into newly opened exit pathways in the beginning of the 1980s and after the transformation. Employment rates were falling following the introduction of early retirement in 1981. Till the transformation, disability pensions were the 29 The aggregate results were not differentiated by sex. The results are all the more striking when we consider than the wording of the question related it to persons who do not work in conditions detrimental to health. 87

preferred way of exit due to easy access criteria and low standard of health of the population. The restricted access to disability pensions in 1997 contributed to their decrease in numbers and to the raising of the average age of take-up of such pensions. Employment rates of Polish men and of Polish women aged 50-54 years are going up since 2005. Relief on the labour market is the foremost explanation. Evasive strategies are another proof of the impact of institutional constraints and opportunities. After the introduction of pre-retirement benefits and allowances and the expiry of early old-age pensions for economic reasons, older workers quickly accommodated to the new options. Following the introduction of early retirement in 1981, early exit gained in acceptance as a deserved phase of life and established an early retirement culture. It is additionally supported by the unparalleled culture of young grandmothers taking care of their working daughters´ children and the belief that early retirement is a just compensation for women´s double burden. Owing to this, most women in Poland retire at the earliest possible age (55 years). An exogenous change of preferences with regard to the expiry of the early retirement for women and certain occupations in 2009 is not visible. There is a continued low acceptance for the equalisation of retirement ages and for the standard retirement age for both men and women (65, resp. 60 years). This can be partially blamed on the back-and-forth policy of all subsequent governments since the pension reform of 1999, especially with regard to bridging pensions. The impact of the new pension system which rewards each year of contributions can be assessed only in the next decade, when the first cohorts will start receiving their old-age pension calculated (partially) according to the changed rules. This is however only a function of long transitory period and does not reduce the validity of hypothesis 4 (see section 2.3.) which is herewith accepted. Institutional changes have an impact on individual life courses, as statutory early exit options were utilised to a great extent shortly after introduction and have given rise to the early exit trend in Poland. 3.3.5. Politics of Social Partners In this section, the Polish industrial relations model will be sketched. This will be the basis for adjusting hypothesis 7 to Polish conditions. Subsequently, the powers of shop-level 88

- Page 47 and 48: I had originally intended to focus

- Page 49 and 50: I chose the software MAXqda for thi

- Page 51 and 52: strategy´, resp. ´muddling throug

- Page 53 and 54: Figure 3: Country-specific analytic

- Page 55 and 56: 3.2.1. Overview of Changes in Pensi

- Page 57 and 58: the early retirement scheme, and fi

- Page 59 and 60: pathway, the flexible and partial p

- Page 61 and 62: was utilised already since the late

- Page 63 and 64: 3.2.2. Overview of Changes in Labou

- Page 65 and 66: criteria of what jobs are they are

- Page 67 and 68: With regard to the legal and collec

- Page 69 and 70: Figure 4: Inflows of men into the p

- Page 71 and 72: of the average retirement age by on

- Page 73 and 74: Figure 8: Employment rates of older

- Page 75 and 76: Institutional changes have also had

- Page 77 and 78: environment, prevention of health i

- Page 79 and 80: urdens of the workforce and suggest

- Page 81 and 82: ased on social insurance and their

- Page 83 and 84: Moreover, “pensions of persons wo

- Page 85 and 86: granted to unemployed women aged 58

- Page 87 and 88: not promote a prolongation of worki

- Page 89 and 90: education vouchers for workers 45+

- Page 91 and 92: force had a low work ethos, low wor

- Page 93 and 94: Figure 9: Annual numbers of recipie

- Page 95 and 96: pensioners decreased by 41 per cent

- Page 97: Figure 11: Employment rates of olde

- Page 101 and 102: espective constituency and inhibits

- Page 103 and 104: Figure 12: Fulfilment of Stockholm

- Page 105 and 106: whom a separate pension system is m

- Page 107 and 108: conducive towards the prolongation

- Page 109 and 110: Due to the negligence in the field

- Page 111 and 112: The position of older workers on th

- Page 113 and 114: fact in Germany rather than in Pola

- Page 115 and 116: 2) the supply-side orientated inter

- Page 117 and 118: Difficulties with recruitment of qu

- Page 119 and 120: learning to the needs of older pers

- Page 121 and 122: (Schmidt/Gatter 1997: 168), in Pola

- Page 123 and 124: 4.2.1. Presentation of the Studied

- Page 125 and 126: Firm DE-14 Man. of Transport Equipm

- Page 127 and 128: opinions by adding that similar tra

- Page 129 and 130: Table 16: Focus of personnel policy

- Page 131 and 132: 4.2.3. Recruitment Practice Good pr

- Page 133 and 134: egardless of their individual capab

- Page 135 and 136: “The movements within the firm -

- Page 137 and 138: epresentative or manager). However,

- Page 139 and 140: The interview guideline for my firm

- Page 141 and 142: tear. However, the externalisation

- Page 143 and 144: publicly owned firms (Firm DE-1, Fi

- Page 145 and 146: At aggregate level, the existence o

- Page 147 and 148: means for „exchanging the old for

preferred way of exit due to easy access criteria and low standard of health of the<br />

population. The restricted access to disability pensions in 1997 contributed to their decrease<br />

in numbers and to the raising of the average age of take-up of such pensions. Employment<br />

rates of Polish men and of Polish women aged 50-54 years are going up since 2005. Relief<br />

on the labour market is the foremost explanation.<br />

Evasive strategies are another proof of the impact of institutional constraints and<br />

opportunities. After the introduction of pre-retirement benefits and allowances and the<br />

expiry of early old-age pensions for economic reasons, older workers quickly<br />

accommodated to the new options.<br />

Following the introduction of early retirement in 1981, early exit gained in acceptance as<br />

a deserved phase of life and established an early retirement culture. It is additionally<br />

supported by the unparalleled culture of young grandmothers taking care of their working<br />

daughters´ children and the belief that early retirement is a just compensation for women´s<br />

double burden. Owing to this, most women in Poland retire at the earliest possible age (55<br />

years).<br />

An exogenous change of preferences with regard to the expiry of the early retirement for<br />

women and certain occupations in 2009 is not visible. There is a continued low acceptance<br />

for the equalisation of retirement ages and for the standard retirement age for both men and<br />

women (65, resp. 60 years). This can be partially blamed on the back-and-forth policy of all<br />

subsequent governments since the pension reform of 1999, especially with regard to<br />

bridging pensions.<br />

The impact of the new pension system which rewards each year of contributions can be<br />

assessed only in the next decade, when the first cohorts will start receiving their old-age<br />

pension calculated (partially) according to the changed rules. This is however only a<br />

function of long transitory period and does not reduce the validity of hypothesis 4 (see<br />

section 2.3.) which is herewith accepted. Institutional changes have an impact on individual<br />

life courses, as statutory early exit options were utilised to a great extent shortly after<br />

introduction and have given rise to the early exit trend in Poland.<br />

3.3.5. Politics of Social Partners<br />

In this section, the Polish industrial relations model will be sketched. This will be the<br />

basis for adjusting hypothesis 7 to Polish conditions. Subsequently, the powers of shop-level<br />

88