70907 for PDF 11/05 - Ivory Classics

70907 for PDF 11/05 - Ivory Classics

70907 for PDF 11/05 - Ivory Classics

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Earl Wild – The Romantic Master<br />

VIRTUOSO PIANO TRANSCRIPTIONS<br />

l l l l l l l l<br />

The word “transcription” comes from transcribe — to write out in full. When applied to the art<br />

of music, it refers to a composition that is arranged or adapted <strong>for</strong> an instrument, voice, or ensemble<br />

other than that <strong>for</strong> which it was originally written. Since the earliest of times composers and<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mers have been arranging, improvising, paraphrasing, borrowing, or recasting popular<br />

themes. Whether in variation <strong>for</strong>m or in elaborate fantasias, themes such as “la Spagna,”<br />

Greensleeves, and many others have appeared penned by many of the great composers.<br />

Variation <strong>for</strong>ms allowed composers to create often elaborate sets of improvisations based on<br />

popular themes of the day. Mozart chose themes by Salieri, Grétry, Gluck, and Duport. Even the<br />

popular French children’s song Ah vous dirai-je, maman yielded a new pianistic masterpiece.<br />

Beethoven, Chopin, Schumann, and Brahms followed suit with incredible works based on themes<br />

by others.<br />

During the 19th century some of the most popular operatic tunes were circulated <strong>for</strong> the amateur<br />

musician as piano potpourris and fantasias by workmanlike composers such as Bendel, Cramer,<br />

Behr, Leybach and others. All the best and most popular tunes of the day were available as piano<br />

transcriptions <strong>for</strong> enjoyment at home. The popularity of this music did not go unnoticed by the<br />

virtuoso pianists of the day. Sigismond Thalberg and Franz Liszt amazed audiences with their extraordinary,<br />

difficult and elaborate improvisations on themes from opera, song, chamber music or<br />

symphonic works.<br />

Franz Liszt (18<strong>11</strong>-1886) was an inveterate transcriber. Whether the melody was a simple folk<br />

song, a complex symphonic work, a lengthy chamber piece, an operatic aria, or a beautiful art-song,<br />

Liszt could not resist the urge to lovingly trans<strong>for</strong>m it into a piano work. More than half of his compositions<br />

are transcriptions, paraphrases, reminiscences, or fantasies on other composers’ music.<br />

Liszt possessed an amazing response to poetic imagery. He believed that purely musical images of<br />

poetic ideas are capable of being projected to the listener and that he could illustrate such imagery<br />

without words. This was his lifelong aesthetic. Liszt transcribed about 150 songs. In addition, he<br />

transcribed <strong>for</strong> piano the complete symphonies of Beethoven, numerous works by Berlioz, Wagner,<br />

Rossini, Weber, and others. Virtually every musical work was grist <strong>for</strong> Liszt’s transcription mill.<br />

Liszt set an incredibly high standard <strong>for</strong> the art of transcription, and it is this standard that was the<br />

– 2 –

influencing factor and guideline <strong>for</strong> virtuoso<br />

pianists who were to follow.<br />

On this disc, we hear transcriptions by four<br />

great pianists of the past, and nine transcriptions<br />

by Earl Wild, the last living link to the great<br />

romantic pianistic traditions of that past.<br />

The least well-known transcriber in this collection<br />

is Pavel (Paul)Pabst (1854-1897). Pabst<br />

was the son of a German organist. He graduated<br />

from the Vienna Hochschule für Musik and took<br />

piano lessons from Franz Liszt. In 1878 Pabst was<br />

invited by Nikolai Rubinstein to join the faculty<br />

of the Moscow Conservatory. After Rubinstein’s<br />

death in 1883, Pabst became the Conservatory’s<br />

director. His influence on Russian musicians was<br />

impressive. Among his students were Konstantin<br />

Igumnov, Nikolai Medtner, Alexander<br />

Goldenweiser, Alexander Gedike, Sergei<br />

Lyapunov, the Conus brothers, and Elena<br />

Bekman-Shcherbina. Pabst was renowned as a<br />

virtuoso pianist, famous as an interpreter of<br />

Liszt’s and Schumann’s music, and an advocate of<br />

Pavel Pabst (1854-1897)<br />

works by his friends Tchaikovsky and Arensky.<br />

He composed an enormous amount of original music, including a virtuosic Piano Concerto and a<br />

beautiful Piano Trio, but it is the brilliant piano paraphrases on themes by Rubinstein and<br />

Tchaikovsky which are best known today. Pabst’s impressive Paraphrase de Concert sur le ballet<br />

“La belle au bois dormant” [Track 5 ] [Paraphrase on Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty] was originally<br />

published by P. Jurgenson in Moscow. A wonderfully elaborate and virtuosic transcription,<br />

Pabst’s paraphrase follows some of Liszt’s models by using musical material from several sections of<br />

the ballet, opening with the dramatic entrance of the wicked fairy Carabosse, who places a curse on<br />

the newborn princess.<br />

Wilhelm Backhaus (1884-1969) was one of the truly great pianists of this century. Born in<br />

Leipzig, he made his debut at the age of eight. At the age of eleven he met Johannes Brahms, a<br />

meeting he would never <strong>for</strong>get. Brahms remained an inspiration throughout his life, yet his later<br />

fame rested on his interpretations of Beethoven’s works. Backhaus studied with Liszt pupil and<br />

– 3 –

legendary pianist Eugen d’Albert. After winning<br />

the Anton Rubinstein Prize in 19<strong>05</strong>, Backhaus<br />

was appointed professor at the Royal College of<br />

Music in Manchester. By the time he made his<br />

American debut in 1912, he was recognized in<br />

many of the leading European capitals as one of<br />

the outstanding living interpreters of the classic<br />

piano literature. That per<strong>for</strong>mance with the New<br />

York Philharmonic also made Backhaus one of<br />

the most famous concert artists in America. One<br />

New York critic wrote: “his type is most unusual.<br />

In appearance he resembles a slender god just<br />

stepped from Olympus. What is more he plays<br />

like a god, too. He is Liszt, Rubinstein and<br />

Paderewski rolled into one. Why he created a<br />

furore is easy to understand.” The New York<br />

Times proclaimed the per<strong>for</strong>mance “brilliant,<br />

crisp, with true poetical feeling.” He continued to<br />

tour the United States through 1926 and became<br />

internationally admired <strong>for</strong> his marvellous<br />

recordings. He returned to New York in 1954 to<br />

sold-out concerts. The two all-Beethoven concerts<br />

at Carnegie Hall in 1956 elicited from<br />

Wilhelm Backhaus (1884-1969)<br />

Harold C. Schonberg, in the New York Times<br />

nothing but admiration and praise: “His playing is immense, monolithic, carved out of granite...<br />

When Mr. Backhaus goes about his work the music emerges in gigantic proportions.” At the age of<br />

eighty, Backhaus undertook to record the 32 Beethoven sonatas <strong>for</strong> the third time, this time in<br />

stereo. By the time he died in 1969 he had completed the project, except <strong>for</strong> one sonata, the<br />

Hammerklavier, Op.106.<br />

In his concerts Backhaus per<strong>for</strong>med an astonishing variety of music. Besides the standard<br />

repertoire by Mozart, Bach, Brahms, Schumann, and Beethoven, he included many compositions<br />

of Liszt and Chopin (he was the very first pianist to record the Chopin’s 24 Études!), and rarities<br />

by Palmgren, Seeling, Herzog, Wertheim, Pick-Mangiagalli, and others. Many of his recitals<br />

included transcriptions by Liszt, Tausig, Dohnányi, Busoni, Siloti, Saint-Saëns, Hutcheson, and,<br />

of course, his own transcription of the Serenade (“Horch auf dem Klang” (Deh vieni alla finestra,<br />

– 4 –

o mio tesoro) from Act II of Mozart’s Don<br />

Giovanni [Track 8 ]. Backhaus’ transcription,<br />

published in 1924, captures the strains of Don<br />

Giovanni’s mandolin Serenade beautifully, retaining<br />

its charm, while being unusually free and<br />

ornate in its pianistic treatment.<br />

Carl Tausig (1841-1871) studied with Liszt<br />

and made his public début in 1858. His life and<br />

career were tragically cut short when he died of<br />

typhoid fever. Musicians and critics agreed that<br />

Tausig was almost Liszt’s equal in grandeur of<br />

interpretation and in technique. As a composer,<br />

Tausig left a legacy of original compositions and<br />

masterful transcriptions. The most difficult of<br />

these were Tausig’s extraordinary transcriptions of<br />

Liszt’s symphonic poems. The transcriptions of<br />

Schubert’s works have remained ever popular,<br />

while Tausig’s five Valse-Caprices on themes by<br />

Johann Strauss, Jr. were published in two books<br />

entitled Nouvelles Soirées de Vienne. The first<br />

group were published by Haslinger in Vienna in<br />

1862. Tausig created these as an addendum to<br />

Liszt’s series (based on Schubert’s works) and dedicated<br />

the set to his teacher. Amy Fay, who studied with Kullak, Tausig and Liszt, wrote extensively<br />

about these works: “Tausig, in my opinion, possessed exceptional genius in compositions, though<br />

he left few works behind him to attest it. Prominent among these are his unique arrangements of<br />

Strauss’ Waltzes. He had a passion <strong>for</strong> philosophy, and was deeply read in Kant and Hegel. These<br />

:arrangements” betray his metaphysical and tentative turn, and could only have been the product<br />

of the highest mental <strong>for</strong>ce and culture. Calling the waltz itself the wrap of the composition, then<br />

through its simple threads we find darting backwards and <strong>for</strong>wards a subtle, complicated, and tragic<br />

sentiment, and a piquant, aerial fancy, until finally is wrought a brilliant and bewildering transcription<br />

— transfiguration rather — of endless fascination and tantalizing beauty, which no one<br />

but a virtuoso can play and no one but a connoisseur can comprehend. In a peculiar manner he<br />

leaves a stamp upon the heart...” Earl Wild per<strong>for</strong>ms the Valse-Caprice No.2 (“Man lebt nur<br />

einmal,” Opus 167) [“One Lives But Once”] [Track 12 ].<br />

– 5 –<br />

Carl Tausig (1841-1871)

The Tausig transcription was a favorite of Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943), who per<strong>for</strong>med it<br />

often and recorded it in 1927. It is difficult to summarize the genius and artistry of Rachmaninov<br />

in just a few sentences. Rachmaninov was a true master musician. Arguably the finest pianist of his<br />

day and renowned also as a conductor, he was, as a composer, one of the most important figures of<br />

Russian late Romanticism. Although his technical and interpretative mastery were incidental to his<br />

creative genius, his recordings continue to fascinate and enthral, <strong>for</strong> no pianist of that era has left<br />

such a treasure trove of extraordinary per<strong>for</strong>mances. As a composer, Rachmaninov left a permanent<br />

and indelible imprint on all pianists who followed him. His Preludes and Concertos are standard<br />

repertoire — every student and serious concertizing pianist plays his music. Simply put,<br />

Rachmaninov’s lyrical gifts carried the Romantic tradition of the 19th century far into the 20th century<br />

and his influence on per<strong>for</strong>mers and composers is still being felt today. Earl Wild has often stated<br />

that “Rachmaninov was the most important musical influence in my life.” Mr. Wild has per<strong>for</strong>med<br />

all of Rachmaninov’s piano compositions, has recorded all of the concertos, and transcribed<br />

thirteen of Rachmaninov’s sumptuous songs. Mr. Wild writes: “The enduring beauty of the songs<br />

gave me the motivation <strong>for</strong> the transcriptions. As a student, I met the famous Russian soprano Maria<br />

Kurenko. Rachmaninov often accompanied her in his songs. Madame Kurenko taught me much<br />

about their interpretation. In particular, I have a deep affection <strong>for</strong> Midsummer Nights, which I find<br />

to be one of Rachmaninov’s loveliest songs.” Midsummer Nights, Opus 14, No.5 [Track 4 ] was<br />

composed by Rachmaninov in September of 1896. Dedicated to Maria Gutheil, the wife of the publisher<br />

who first issued Rachmaninov’s songs, this song is a setting of the poem by Dmitri Rathaus<br />

(translated <strong>for</strong> the Gutheil edition by Edward Agate):<br />

Oh these midsummer nights all in splendor set,<br />

Steeped in wonder of moonlight that reigns serene,<br />

They awaken the promise of ecstasy,<br />

And rekindle the passion of love’s desire.<br />

From this sorrowful heart, they will lift the load,<br />

Weight of woe unto mortals by life decreed,<br />

And the borders of happiness open wide,<br />

The spell obeying, that silent its work is weaving...<br />

And the gates of the spirit are barr’d no more,<br />

For its regions are flooded with waves of love,<br />

Oh, these midsummer nights all in splendor set,<br />

Clad in magic of moonlight that reigns supreme.<br />

Earl Wild’s transcription of this marvelous song was completed in 1981.<br />

– 6 –

Rachmaninov’s own transcription of Fritz<br />

Kreisler’s delicious violin work, Liebesleid<br />

(“Love’s Sorrow”) [Track 13 ] was first per<strong>for</strong>med<br />

by Rachmaninov at a concert in Chicago on<br />

November 20, 1921. Kreisler wrote this as part of<br />

a trilogy of Alt Wiener Tanzweisen (“Old Viennese<br />

Dance Melodies”). When Rachmaninov recorded<br />

his own transcription on a reproducing piano roll<br />

<strong>for</strong> the Ampico Corporation, they published the<br />

following in<strong>for</strong>mation in their catalogue:<br />

“Kreisler’s beautiful old Viennese dance melodies<br />

have delighted thousands of music lovers who<br />

have heard them. There is a plaintive appeal in<br />

these dance melodies of a far-off time, recalling<br />

the festivities of other days, when the waltz<br />

rhythm was a newly discovered delight. They<br />

come with much charm inseparable from folk<br />

music, and bear the unmistakable stamp of their<br />

Viennese origin. Rachmaninov has taken one of<br />

the loveliest, a love song, and added embellishments<br />

of his own that set it <strong>for</strong>th in a new dress,<br />

but with all its original beauty shining through<br />

the shimmering filigree with which he adorns it.”<br />

In 1881, when Saint-Saëns was elected to<br />

the Institut de France someone said, “If it were<br />

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)<br />

necessary to characterize Saint-Saëns in a few<br />

words we should call him the best musician in<br />

France.” He was a man of extraordinary, and seemingly inexhaustible, energy and drive. He was<br />

an expert organist and pianist, teacher, founder of the Société Nationale de Musique. He edited<br />

the music of other composers, including a comprehensive edition of Rameau’s works, and wrote<br />

theoretical treatises on harmony and melody. Beyond all this he was an amateur astronomer,<br />

physicist, archaeologist, and natural historian. He painted and did creative writing, enjoyed<br />

learning new languages, and was an omnivorous reader of the classics. In short, Saint-Saëns was<br />

a man of immense culture.<br />

Saint-Saëns was a master craftsman who had an unerring musical sense and an astonishing<br />

– 7 –

ability to produce masterpiece after masterpiece. He left an astonishing volume of work including<br />

thirteen operas (of which Samson et Dalila is considered one of the greatest works of the French<br />

lyric stage), ten concertos (including the delightful Carnival of the Animals <strong>for</strong> two pianos and<br />

orchestra), seven symphonies, numerous choral works, over a hundred songs, symphonic poems,<br />

piano compositions and chamber sonatas <strong>for</strong> violin, cello, clarinet, oboe and bassoon. He also wrote<br />

works <strong>for</strong> military band, cadenzas to piano concertos of Mozart and Beethoven, and transcribed<br />

and arranged numerous works by Bach, Gluck, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Berlioz, Mozart and others.<br />

“Of all composers, Saint-Saëns is most difficult to describe,” wrote Arthur Hervey. “He eludes<br />

you at every moment — the elements constituting his musical personality are so varied in their<br />

nature, yet they seem to blend in so remarkable a fashion... Saint-Saëns is a typical Frenchman...<br />

He is preeminently witty... It is this quality which has enabled him to attack the driest <strong>for</strong>ms of art<br />

and render them bearable. There is nothing ponderous about him.”<br />

In the period after the Franco-Prussia War, Saint-Saëns helped to found the National Society of<br />

Music <strong>for</strong> the encouragement of French instrumental composition. About this same time the preoccupation<br />

with the théâtre among French composers began to slack off a little and representatives<br />

of a new symphonic school came <strong>for</strong>ward. It was in this set of circumstances that the four symphonic<br />

poems — Le Rouet d’Omphale, Op.31; Phaëton, Opus 39; Danse Macabre, Opus 40; and<br />

La Jeunesse d’Hercule, Opus 50 — were conceived. Their part in giving prestige to the new French<br />

symphonists was a most important one.<br />

Le Rouet d’Omphale, Opus 31 [Omphale’s Spinning Wheel] [Track 1 ] was Saint-Saëns’ first<br />

attempt at tone-painting. On the face of it, the music depicts the whirling and whirring of the wheel<br />

used in spinning flax into linen thread. According to legend, the spinner is not Omphale, we are<br />

told but Hercules, who got himself in trouble with the gods and was put into bondage to Omphale<br />

<strong>for</strong> three years. Apparently to humiliate him, Omphale put him to spinning while dressed in<br />

women’s clothing. The moaning theme introduced in the middle of the piece is said to be old<br />

Hercules groaning under the burden of it all. On the flyleaf of the original piano score, Saint-Saëns<br />

added a further note: “The subject of this symphonic poem is feminine seductiveness, the triumphant<br />

contest of weakness against strength. The spinning wheel is merely a pretext; it is chosen<br />

simply <strong>for</strong> the sake of its rhythmical suggestion and from the viewpoint of the general <strong>for</strong>m of the<br />

piece.” As a model Earl Wild does not use Saint-Saëns’ own rather spare piano version, but returns<br />

to the original orchestral score, incorporating many orchestral effects into his 1995 transcription.<br />

Tchaikovsky was most com<strong>for</strong>table writing music <strong>for</strong> the ballet, opera, and symphony orchestra.<br />

Although he composed <strong>for</strong> the piano extensively and throughout all of his creative life, the<br />

bulk of the music — over one hundred pieces — consists of collections of morceaux, mostly<br />

waltzes, scherzi and other short pieces intended <strong>for</strong> the piano enthusiast per<strong>for</strong>ming in a family<br />

– 8 –

salon. Tchaikovsky, even in the larger <strong>for</strong>ms, was never completely at ease writing <strong>for</strong> the piano.<br />

This may be because he always considered himself a “piano player” rather than a “pianist.” The distinction<br />

is important, in that, <strong>for</strong> Tchaikovsky the piano was a means to an end — an instrument<br />

to try out ideas, audition symphonic works, or accompany the voice. Earl Wild’s 1975<br />

transcription of Tchaikovsky’s “Dance of the Four Swans” (Pas de Quatre, Act 2) from Swan Lake,<br />

Opus 20 (1875/76) [Track <strong>11</strong> ] is a pure delight. Not to be mistaken <strong>for</strong> the “Dance of the Little<br />

Swans” which occurs in Act 4 of the ballet, the “Dance of the Four Swans” takes place in Act 2, just<br />

prior to the Pas d’action. Swan Lake is one of the greatest ballets of all time — a Germanic fairy<br />

tale, in which Prince Siegfried woos Odette, Queen of the Swan Maidens. The Swan Maidens are<br />

swans only by day, being trans<strong>for</strong>med back to their original state at night by the magician Rotbart,<br />

under whose spell they exist. Naturally, Siegfried has a hard time winning Odette away from<br />

Rotbart’s magic power, but in the end he finally succeeds. Earl Wild’s transcription of Tchaikovsky’s<br />

memorable and haunting romance from 1878, At the Ball (“Sred shumnovo bala”), Opus 38,<br />

No.3 [Track 10 ] captures the music’s gentle poignancy reflecting the more inward feelings stirred<br />

by a beautiful woman glimpsed across a crowded and noisy ballroom. The poem by Aleksey Tolstoy<br />

(1817-1875) attracted Wild to transcribe the song in 1992.<br />

Amid the din of the ball in the tumult of everyday bustle,<br />

I chanced to see you, but a secret veiled your features;<br />

Only your eyes looked on sadly, but your voice sounded so divine,<br />

Like the sound of a distant pipe, like the sea’s playful wave.<br />

I loved your slender figure and your pensive look,<br />

And your laughter, at once sad and vibrant,<br />

Has rung out in my heart since then!<br />

When, in the lonely hours of the night,<br />

I am weary and would lie down to rest,<br />

I see your sad eyes, and hear your happy voice.<br />

Then sadly, so sadly, I sink into sleep, a sleep of dreams beyond recall.<br />

I do not know if I love you, but it seems to me that I do!<br />

Gabriel Fauré was born in Pamiers, Ariege, France, May 13, 1845; he died in Paris, November<br />

4, 1924. As a youth he had every musical advantage. He studied under the best teachers, including<br />

Saint-Saëns, Niedermeyer and Dietsch. He progressed rapidly as composer, organist and teacher.<br />

His first professional position was that of organist at St. Sauveur, at Rennes; later he returned to<br />

Paris, and after occupying various rather minor posts as organist, he was made accompanying<br />

organist at St. Sulpice, where the late and beloved Charles-Marie Widor was at one time principal<br />

– 9 –

organist. Still later he accepted the principal post of maitre de chapelle at the Church of the<br />

Madeleine, becoming organist of this famous basilica in 1896. About the same time he took up<br />

his duties as a professor of composition at the Paris Conservatory, where he advanced continually<br />

until in 19<strong>05</strong> he held the post of director in succession to the organist, Theodore Dubois. With<br />

this appointment began a period of great accomplishment. As a teacher his influence has been felt<br />

to the present day, not only in the music of France but among all the composers who have ever<br />

studied in that country. Among his pupils whose gifts he developed and encouraged were such<br />

colossal figures as Nadia Boulanger, Roger-Ducasse, Aubert, Ravel, Laparra, Florent Schmitt and<br />

many others.<br />

Of the Fauré songs, the best known are, perhaps, Les Roses d’Ispahan, Opus 39, No.4 (1884)<br />

and Après un rêve, Opus 7, No.1 (1878) — but there is a large number of others, equally beautiful.<br />

In his 1992 transcription of Faure’s Après un rêve (“After a Dream”) [Track 6 ], Earl Wild is mindful<br />

of not only the words but also Lotte Lehmann’s sage advise: “Begin this song as if still in a<br />

dream... it is also important that each phrase be sung with a swing, with a soft rise and fall... Begin<br />

with a delicate ecstasy and don’t <strong>for</strong>get that some of the phrases are silvery, very bright, very ethereal.”<br />

The anonymous words are radiant:<br />

In a slumber, charmed by your image,<br />

I dreamed of happiness - ardent mirage.<br />

Your eyes were more gentle, your voice pure and clear.<br />

You were radiant like a sky brightened by sunrise.<br />

You called me and I left the earth to flee with you towards the light.<br />

The skies opened their clouds to us —<br />

splendors unknown — glimpses of divines light.<br />

Alas, alas, sad awakening from dreams!<br />

I call to you, oh night, give me back your illusions.<br />

Return, return with your radiance, return, oh mysterious night!<br />

A few of the great composers showed exceptional talents when very young. Although some,<br />

such as Mozart, were “infant prodigies” it is not to be taken <strong>for</strong> granted (although it sometimes is)<br />

that all composers of genius belonged to this class. George Frideric Handel’s development was<br />

steady rather than spectacular and while his achievement was considerable by the time he took<br />

English nationality at the age of <strong>for</strong>ty-one his best known works — in almost every field — were<br />

yet to come.<br />

A year after George I had confirmed Handel’s British citizenship and appointed him to the<br />

post of Court composer, <strong>for</strong> which he was now eligible, he died and was succeeded by George II.<br />

– 10 –

In October, 1727, the Coronation took place and Handel composed four anthems <strong>for</strong> voices and<br />

orchestra to celebrate the occasion. By the time he began composing his twelve Concerti Grossi,<br />

Opus 6 he was at the height of his powers. On January 16, 1739, he had led the per<strong>for</strong>mance of<br />

his oratorio Saul at the King’s Theatre. He had completed this work in September, 1738, and only<br />

four days later, on October 1, plunged into Israel in Egypt, which he composed in the space of<br />

about three weeks, a feat that remains incredible, even when we grant the fact that he used a great<br />

deal of music by other composers in this work. On April 4, 1739, Israel in Egypt was per<strong>for</strong>med.<br />

Although it was at first a failure, Handel was to be amply consoled two years later, in 1741, with<br />

the success of Messiah. Considering the rate at which Handel was producing masterpiece after<br />

masterpiece, we might expect to find something feverish, something overdriven, in the Concerti<br />

Grossi. But we find nothing of the kind. It is true, as Romain Rolland and others have pointed<br />

out, that this music has the nature of a constant improvisation. Rolland adds that it must be<br />

“served piping hot”! Yet so colossal were Handel’s musical powers, so sure was his hand, that he<br />

could throw off completely <strong>for</strong>med and balanced works that unite classical beauty with the utmost<br />

freedom of imagination.<br />

Handel composed sixteen keyboard suites which were published between 1720 and 1733. The<br />

Suite No.5 in E Major, contains four movements, concluding with Handel’s most famous keyboard<br />

work, the so-called “Harmonious Blacksmith.” The title accorded this Air con Variazioni cannot be<br />

found in any publication prior to the 19th century. The movement is a straight <strong>for</strong>ward air with<br />

five variations which become progressively more elaborate. In his 1993 transcription of the Air and<br />

Variations - “The Harmonious Blacksmith” [Track 2 ], Mr. Wild shows his consummate knowledge<br />

of 18th century per<strong>for</strong>mance practices. Earl Wild has stated that he incorporated the “many<br />

benefits of the double-keyboard harpsichord in preparing the score <strong>for</strong> modern piano. I was also<br />

very influenced by the per<strong>for</strong>mances I heard of this work as a child by great masters such as Moritz<br />

Rosenthal and Sergei Rachmaninov.” According to composer and musicologist, Hubert Parry, the<br />

story of the “Harmonious Blacksmith” arose from a mythical account of Handel “being caught in<br />

a shower of rain while walking near Cannons. Handel took refuge in a blacksmith’s shop, where he<br />

heard the blacksmith whistling or singing the famous tune to the accompaniment of the ringing<br />

sound of the anvil.” A pleasant story, now proven to be baseless.<br />

Critic Jay Harrison once stated that “In many ways, Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) is Paris. He<br />

is gay like Paris, sad like Paris. And he bustles constantly. His hands wave, his eyebrows arch, he<br />

twitches, grins, makes faces. When his mouth talks, all of him talks too. If he is not Paris, he is at<br />

least French. Not even a deaf man could doubt that.” And certainly that is also true of Poulenc’s<br />

music. In much of his music (the finest examples being his Suite française, a transcription of seven<br />

dances by Claude Gervaise, and his Valse-improvisation sur le nom de BACH dedicated to Vladimir<br />

– <strong>11</strong> –

Horowitz) Poulenc combined the old with the new. His style was at times sweetly melancholic<br />

mixed with liberal dashes of wry dissonances and haunting, plaintive melodies. No other 20th century<br />

composer created music in this style, vigorous, whimsical and peppery. Earl Wild’s Hommage<br />

à Poulenc (1995) [Track 7 ] is in essence an improvisation “in the style” of Poulenc based on Bach’s<br />

Sarabande, from the Partita No.1 in B flat Major, BWV 825. Mr. Wild writes: “One day I happened<br />

to be playing the well-known Sarabande from Bach’s Partita No.1. Suddenly, I wondered how it<br />

might sound in a Poulenc setting. This notion intrigued me since Bach and Poulenc are two composers<br />

often thought to be incompatible. I realized it was truly an homage to Poulenc, whom I<br />

found to be a very gracious and generous man.”<br />

The recent celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of Walt Disney’s Snow White included its first<br />

release on videotape. Earl Wild comments: “Watching Snow White brought back so many vivid<br />

memories of the past that I wanted to write something making use of these enchanting tunes by<br />

Frank Churchill.” Frank Churchill (1901-1942) was a pianist and composer, educated at the<br />

University of Cali<strong>for</strong>nia, Los Angeles. Among the marvelous scores he composed during his tenure<br />

with Walt Disney were Three Little Pigs (1933) which included the universally recognized song,<br />

“Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?,” Dumbo (which won him the Academy Award in 1941), Snow<br />

White and The Seven Dwarfs (1938), and Bambi (1942). Earl Wild’s own sense of humor adds to<br />

the charm of the original music, developing these reminiscences (of the marvelous songs: “Whistle<br />

While You Work”; “I’m Wishing”; “One Song”; “Heigh-Ho”; and “Someday My Prince Will<br />

Come”) into a personal statement that pays homage to the feature-length animated film. It is one<br />

of the few uniquely American art <strong>for</strong>ms. Earl Wild completed the Reminiscences of Snow White<br />

[Track 9 ] in 1995, dedicating the work to Barbara Sokol.<br />

Contemporaries of Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) reported that he often played <strong>for</strong> them a solo<br />

version of the Larghetto from the Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 [Track 3 ]. Franz Liszt<br />

called this movement “resplendent with rare dignity of style, and containing passages of wondrous<br />

interest and astonishing grandeur. The whole movement is of an almost ideal perfection; its expression<br />

is now radiant with light and anon full of tender pathos.” Hermann Scholtz, another celebrated<br />

pianist, who transcribed the movement <strong>for</strong> solo piano in the 19th century, wrote: “It is a<br />

piece full of poetic charm. In it all the attributes of a perfect work of art appear in the happiest<br />

union; noble melody, choice harmonies, agreeable figures, and the perfection of <strong>for</strong>m, while the<br />

thoroughly original ideas are finely contrasted.” Earl Wild states: “The dramatic middle section,<br />

which is accompanied by a tremolo in the orchestra, necessitated a total adjustment in transcribing<br />

this work <strong>for</strong> solo per<strong>for</strong>mance.” Mr. Wild’s transcription was completed in 1985.<br />

– 12 –<br />

— Notes by Marina and Victor Ledin, © 1999.

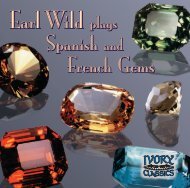

EARL WILD<br />

“When Earl Wild per<strong>for</strong>ms, the Golden Age of the keyboard suddenly reappears.”<br />

TIME Magazine (1995)<br />

l l l l l l l l<br />

Earl Wild is a pianist in the grand<br />

Romantic tradition. His legendary<br />

career, so distinguished and long, has<br />

continued <strong>for</strong> well over 70 years.<br />

Born in 1915, in Pittsburgh,<br />

Pennsylvania, Earl Wild’s technical<br />

accomplishments are often likened to<br />

what those of Liszt himself must have<br />

had. Born with absolute pitch he<br />

started playing the piano at three.<br />

Having studied with great pianists<br />

such as Egon Petri, his lineage can be<br />

traced back to Scharwenka, Busoni,<br />

Ravel, d’Albert and Liszt himself.<br />

Earl Wild’s career is dotted with<br />

musical legends. As a young pianist<br />

he was soloist with Arturo Toscanini<br />

and the NBC Symphony. Since then<br />

he has per<strong>for</strong>med with virtually every<br />

major conductor and symphony<br />

orchestra in the world. Rachmaninov<br />

was an important idol in his life. It’s<br />

been said of Earl Wild, “He’s the<br />

incarnation of Rachmaninov,<br />

Lhevinne and Rosenthal rolled into<br />

one!” In 1986 after hearing him play<br />

three sold-out Carnegie Hall concerts,<br />

devoted to Liszt, honoring the<br />

Earl Wild<br />

– 13 –

centenary of that composer’s death, one critic said, “I find it impossible to believe that he played<br />

those millions of notes with 70-year-old fingers, so fresh-sounding and precise were they. Perhaps<br />

he has a worn-out set up in his attic, a la Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray.”<br />

He’s one of the few American pianists to have achieved international as well as domestic celebrity.<br />

He has per<strong>for</strong>med <strong>for</strong> six Presidents of the United States, beginning with Herbert Hoover, and<br />

in 1939, was the first classical pianist to give a recital on the new medium of Television. At fourteen<br />

he was per<strong>for</strong>ming in the Pittsburgh Symphony with Otto Klemperer as well as working at<br />

radio station KDKA, where he played many of his own compositions. As a virtuoso pianist, composer,<br />

transcriber, conductor, editor and teacher, Mr. Wild continues in the style of the legendary<br />

great artists of the past.<br />

In addition to his distinguished concert career, which encompasses per<strong>for</strong>mances with other<br />

eminent conductors such as Stokowski, Reiner, Maazel, Solti and Mitropoulos, and artists like<br />

Callas, Tourel, Pons, Melchior, Peerce and Bumbry, Wild successfully shines as both a conductor<br />

and composer. His Easter oratorio, Revelations, was broadcast by the ABC network in 1962 and<br />

again in 1964. Wild’s most recent composition, Variations on a Theme of Stephen Foster <strong>for</strong> piano<br />

and orchestra (“Doo-Dah” Variations), premiered with Wild as soloist with the Des Moines<br />

Symphony Orchestra in 1992.<br />

Earl Wild has been called “the finest transcriber of our time,” and his piano transcriptions are<br />

widely known and respected.<br />

This eminent pianist has built an extensive repertoire over the years, which includes both the<br />

standard and modern literature. He has become world renown in particular <strong>for</strong> his brilliant per<strong>for</strong>mances<br />

of the virtuoso Romantic works. Today at 84, Mr. Wild continues to record and per<strong>for</strong>m<br />

concerts throughout the world. In 1997, he won a Grammy ® Award <strong>for</strong> this disc, “The Romantic<br />

Master” – Virtuoso Piano Transcriptions. Praised by critics and music lovers around the world as a<br />

“stunning document of musical sensitivity and virtuosity” and “a tribute to America’s greatest<br />

pianistic treasure” — this CD is once again available in its original HDCD state-of-the-art audiophile<br />

sound.<br />

When he was 79, he recorded a well received Beethoven disc which included the monumental<br />

Hammerklavier Sonata, as well as another disc composed of Rachmaninov’s Preludes and the Second<br />

Piano Sonata. Mr. Wild was also included in Philips’ Great Pianists of the 20th Century series with<br />

a double CD devoted to piano transcriptions. As an <strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> ® artist, he has just recorded three<br />

20th century piano sonatas by Barber, Hindemith and Stravinsky as well as a sonata of his own,<br />

which will be released in the year 2000 (his 85th birthday year).<br />

– 14 –

CREDITS<br />

Recorded in Fernleaf Abbey, Columbus, Ohio, May 7-<strong>11</strong>, 1995<br />

20-bit HDCD encoded<br />

Producer: Michael Rolland Davis<br />

Engineer: Ed Thompson<br />

Piano Technician: Andrei Svetlichny<br />

Special thanks to the Michael Palm Foundation<br />

This disc is dedicated to the memory of Michael Palm and Andrei Svetlichny<br />

Liner Notes: Marina and Victor Ledin<br />

Design: Communication Graphics<br />

Inside Tray Photo: Earl Wild’s 1997 Grammy ® Award<br />

This disc was previously released in 1995 on Sony Classical [SK62036]<br />

Printed Scores of Earl Wild’s Transcriptions are available from:<br />

Michael Rolland Davis Productions, Publisher, ASCAP<br />

2233 Fernleaf Lane • Columbus, Ohio 43235 USA<br />

Phone: (614) 761-1755 • Fax: (614) 761-9799<br />

All of Mr. Wild’s Transcriptions are ASCAP<br />

To place an order or to be included on mailing list:<br />

<strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> • P.O. Box 341068 • Columbus, Ohio 43234-1068<br />

Phone: 888-40-IVORY or 614-761-8709 • Fax: 614-761-9799<br />

e-mail@ivoryclassics.com • Website: http://www.<strong>Ivory</strong><strong>Classics</strong>.com<br />

– 15 –

Earl Wild<br />

Virtuoso Piano Transcriptions<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

<strong>11</strong><br />

12<br />

13<br />

Saint-Saëns /Wild: Le Rouet d’Omphale, Op.31 8:12 *<br />

Handel /Wild: Air and Variations – The Harmonious Blacksmith 4:26 *<br />

Chopin /Wild: Larghetto, from Piano Concerto No.2 in F minor, Op.21 9:17 *<br />

Rachmaninov /Wild: Midsummer Nights, Op.14, No.5 3:26<br />

Tchaikovsky / Pabst: Paraphrase on Sleeping Beauty 6:58 *<br />

Fauré /Wild: Improvisation on “Après un rêve” 2:40 *<br />

Bach /Wild: Hommage à Poulenc 4:23 *<br />

Mozart / Backhaus: Serenade from Don Giovanni 2:42<br />

Churchill /Wild: Reminiscences of Snow White 7:49 *<br />

“Whistle While You Work” – “I’m Wishing” – “One Song” –<br />

“Heigh-Ho” – “Someday My Prince Will Come”<br />

Tchaikovsky /Wild: At the Ball, Op.38, No.3 3:00 *<br />

Tchaikovsky /Wild: Dance of the Four Swans from Swan Lake 1:40<br />

Johann Strauss, Jr./Tausig: Man lebt nur einmal 7:22<br />

Kreisler / Rachmaninov: Liebesleid 4:40<br />

Total Playing Time: 66:54 • *World Premiere Recording<br />

Producer: Michael Rolland Davis • Engineer: Ed Thompson<br />

1999 <strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> ® • All Rights Reserved. 644<strong>05</strong>-<strong>70907</strong> STEREO<br />

<strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> ® • P.O. Box 341068<br />

Columbus, Ohio 43234-1068 U.S.A.<br />

Phone: 888-40-IVORY or 614-761-8709 • Fax: 614-761-9799<br />

®<br />

e-mail@ivoryclassics.com • Website: www.<strong>Ivory</strong><strong>Classics</strong>.com