Ruth Slenczynskaâ¢SCHUMANN Ruth Slenczynska ... - Ivory Classics

Ruth Slenczynskaâ¢SCHUMANN Ruth Slenczynska ... - Ivory Classics

Ruth Slenczynskaâ¢SCHUMANN Ruth Slenczynska ... - Ivory Classics

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

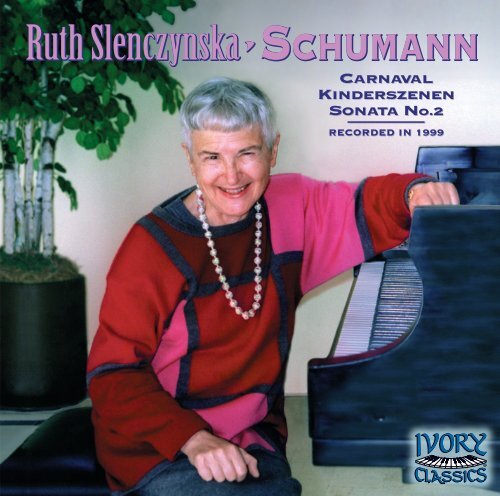

<strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong>•SCHUMANN<br />

CARNAVAL<br />

KINDERSZENEN<br />

SONATA No.2<br />

RECORDED IN 1999

Schumann<br />

Carnaval • Kinderszenen • Sonata No.2<br />

Carnaval (“Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes”), Opus 9 28:46<br />

1 Préambule. Quasi maestoso – Più moto – Animato – Vivo – Presto 2:12<br />

2 Pierrot. Moderato 0:51<br />

3 Arlequin. Vivo 1:03<br />

4 Valse noble. Un poco maestoso 2:01<br />

5 Eusebius. Adagio 1:30<br />

6 Florestan. Passionato 0:55<br />

7 Coquette. Vivo 1:02<br />

8 Réplique. L’istesso tempo 0:25<br />

9 Papillons. Prestissimo 0:53<br />

10 A.S.C.H.-S.C.H.A. (letteres dansantes). Presto 0:57<br />

11 Chiarina. Passionato 1:18<br />

12 Chopin. Agitato 1:36<br />

13 Estrella. Con affetto 0:29<br />

14 Reconnaissance. Animato 1:46<br />

15 Pantalon et Colombine. Presto 0:56<br />

16 Valse allemande. Molto vivace 1:02<br />

17 Paganini. Intermezzo. Presto 1:29<br />

18 Aveu. Passionato 1:14<br />

19 Promenade. Comodo 2:48<br />

20 Pause. Vivo 0:18<br />

21 Marche des “Davidsbündler” contre les Philistins. Non Allegro –<br />

Molto più vivo – Animato – Vivo – Animato molto – Vivo – Più stretto 3:51<br />

– 2 –

<strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong>, Pianist<br />

Original 24-Bit Master<br />

Kinderszenen (“Scenes from Childhood”), Opus 15 18:15<br />

22 I. Von fremden Ländern und Menschen (Foreign lands and people) 1:58<br />

23 II. Kuriose Geschichte (Curious story) 1:08<br />

24 III. Hasche-Mann (Catch me if you can) 0:33<br />

25 IV. Bittendes Kind (Pleading child) 1:02<br />

26 V. Glückes genug (Happiness) 1:08<br />

27 VI. Wichtige Begebenheit (Important Event) 0:49<br />

28 VII. Träumerei (Dreaming) 2:42<br />

29 VIII. Am Kamin (By the fireside) 0:59<br />

30 IX.Ritter vom Steckenpferd (Knight of the hobby-horse) 0:40<br />

31 X. Fast zu ernst (Almost too serious) 1:53<br />

32 XI. Fürchtenmachen (Frightening) 1:10<br />

33 XII. Kind im Einschlummern (Child falling asleep) 2:03<br />

34 XIII. Der Dichter spricht (The poet speaks) 2:14<br />

Sonata No.2 in G Minor, Opus 22 18:50<br />

35 I. So rasch wie möglich 7:20<br />

36 II. Andantino (Getragen) 3:48<br />

37 III. Scherzo: Sehr rasch und Markiert 1:48<br />

38 IV. Rondo: Presto 5:54<br />

Total Playing Time: 66:07<br />

– 3 –

Robert Schumann<br />

In the introduction to his critical writing, Robert Schumann bewailed the lack of good<br />

contemporary music. “On the stage Rossini reigned; at the piano nothing was heard but<br />

Herz and Hunten; and yet but a few years had passed since Beethoven, Schubert and Weber<br />

had lived among us.” That was written about 1833, when Schumann founded the Neue<br />

Zeitschrift für Musik, and was also well started on a noble series of piano works.<br />

As editor of the Neue Zeitschrift it was Schumann’s fancy often to sign his reviews with<br />

pen names, and people them with pen names that stood for his friends. Wherever Zilia or<br />

Chiarina appears, Clara Wieck (later to become Schumann’s wife) is understood. Meritas<br />

refers to Felix Mendelssohn; Florestan and Eusebius reflect the passionate or reflective sides<br />

of Schumann’s nature. And so on.<br />

While editing the Zeitschrift, Schumann also was doing his best to write piano music that<br />

would be a corrective to Herz and Hünten. The Carnaval, Opus 9, which dates from 1834-<br />

35, is subtitled “Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes.” But why “tiny scenes on four notes?”<br />

Well, Schumann had fallen in love with a girl named Ernestine von Fricken, and she came<br />

from a town named Asch. Each of the four letters in the name of that town has, a musical<br />

equivalent in German. “S” is the same as “Es,” which is our E flat. The German “H” is our B<br />

natural. These four letters — ASCH — also occur in Schumann’s name. Moreover, “As” in<br />

German is A flat. Thus Schumann exuberantly went to work, devising a triple set of themes<br />

— A, E flat, C, B; A flat, C, B; E flat, C, B, A. The first group of notes in nearly every piece<br />

of the Carnaval is based on one of those three combinations.<br />

“Let me make a few observations regarding this composition,” wrote Schumann, “which<br />

owed its origin to pure chance. The name of a city in which a musical friend of mine lived<br />

consisted of letters belonging to the scale which are also contained in my name, and this suggested<br />

one of those musical games that are no longer new, since Bach provided the model.<br />

One piece after the other was completed during the carnival season of 1835, in a serious<br />

mood, by the way, and under peculiar circumstances. I afterwards gave titles to the numbers,<br />

and named the entire collection Carnaval.”<br />

The work opens with a spirited Préambule. After the trumpet-call opening, a brillante<br />

section follows, ending in a kind of Gilbert and Sullivan summation. Then Pierrot, the stumbling<br />

clown makes his pompous way across the stage, joined by Arlequin in the next number.<br />

A Valse noble follows where right hand octaves introduce the expressive melody. Next the<br />

– 4 –

dual parts of Schumann’s personality<br />

are paired off: Eusebius<br />

(the title is Schumann’s alias<br />

for the softer side of his<br />

own personality) and Florestan<br />

(Schumann the man of action).<br />

It is interesting to note that<br />

Florestan has the same initial<br />

sequence of notes as the Valse<br />

noble, but how differently<br />

Schumann treats the two!<br />

Coquette comes on stage, traipsing<br />

right out of Florestan in a<br />

flirty waltz; there is a reply<br />

(Réplique); and then the funny<br />

little Sphinxes appear which are<br />

never played, nor are they<br />

meant to be, but which give the<br />

clue to the Carnaval by printing<br />

the three thematic combinations<br />

that Schumann evolved<br />

from the good city of Asch.<br />

Three forms of the musical<br />

cryptogram are given in<br />

Sphinxes. First is a four note<br />

idea, E flat, C, B, A, standing<br />

for SCHA, an abbreviation for<br />

Robert and Clara Schumann<br />

Schumann (SCHumAnn).<br />

Then come the three notes A flat, C, B, standing for Asch, using A flat as AS. The third is a<br />

four note phrase A, E flat, C, B, standing again for Asch. The game doesn’t end there,<br />

though, for each piece is as well a miniature cartoon or caricature of a friend, a composer, or<br />

one of the figures of Italian comedy, with an occasional valse or mood piece thrown in.<br />

The whole is then wrapped up as a document of the Davidsbündler, Schumann’s imaginary<br />

– 5 –

society for the prevention of cruelty to Romantic composers.<br />

In the music the sequence continues as follows: Papillons (a fluttery version of<br />

Schumann’s butterflies), Lettres Dansantes (in which the cryptogram ASCH and SCHA<br />

become the subject now of a slightly frenzied dance that ends abruptly), Chiarina (this waltz<br />

is meant to be a characteristic description of Clara Wieck, later to become Schumann’s wife.<br />

Annotators have remarked that even here the composer seems to have given her a favored<br />

position and musical treatment), Chopin (in which Schumann, as a tribute, imitates the composer’s<br />

delicate nocturne-like writing), and Estrella (Ernestine von Fricken). Next come the<br />

Reconnaissance, one of the most delightful of the pieces. Its title can be taken to mean<br />

acknowledgement or recognition but could also mean a reconnaissance in the sense of military<br />

reconnoitering of a personal kind. It is followed by those two good carnival figures,<br />

Pantalon et Colombine, providing us with more Italian comics before the footlights. A Valse<br />

Allemande is interrupted by none other than Paganini, bowing violently away. Then there is<br />

the tender Aveu, a short, simple confession. It is followed by a Promenade, a three-quarter<br />

time stroll in a peaceful, somewhat idealistic garden. Pause is next – this “pause” is, rather, a<br />

short headlong dive into the conclusion.<br />

The finale is entitled Marche des “Davidsbündler” contre les Philistins. The Davidsbündler<br />

was a typical Schumannesque invention, supposed to represent a group consisting of the<br />

composer and his friends – a band dedicated to artistic ideals and the prevention of cruelty to<br />

Romantic composers. Liszt introduced Carnaval in a Leipzig concert but the work proved<br />

too full of startling ideas compactly presented to be immediately heard for what it is. As Liszt<br />

later wrote: “The musicians, as well as the so-called musical experts, with few exceptions, still<br />

wore a thick mask over their ears, which prevented them from comprehending this piece, so<br />

charming, so bejewelled, and, through artistic imagination, so variously and harmoniously<br />

put together.”<br />

The miracle of the Carnaval, Opus 9 is the bewildering variety Schumann achieves<br />

despite the limiting factor of the three themes to which he confined himself. To many, this<br />

work is the cornerstone of the romantic period in music. The programme is secondary: it is<br />

mildly amusing and even wistful, these sophisticated days. As pure music, forgetting entirely<br />

about the programme, the Carnaval is a glowing, nostalgic, passionate and idealistic outpouring<br />

from one of the most poetic musicians who ever lived.<br />

Music, as Schumann composed it, was meant to be expressive in itself. He possessed not<br />

only a rare spiritual affinity to poetry, but also the soul and imagination of a poet. In his sets<br />

– 6 –

of descriptive piano pieces bearing individual titles (“Fantasiestücke,” Opus 12 in 1837<br />

was the first among them) he in effect created the equivalent of song cycles for the piano, as<br />

colorful and poetic as the best inspirations of his celebrated lieder.<br />

Kinderszenen, Opus 15 dates from 1838, when Schumann was twenty-eight. It was a particularly<br />

happy and productive year for the composer. Thoughts of Clara Wieck had filled<br />

his mind and guided his pen. Composing prodigiously, he dashed off the entire set in a matter<br />

of days. “I felt as if I had wings, and wrote about thirty pretty little things from which I<br />

have chosen twelve and called them “Kinderszenen.” I am very proud of them...” These are<br />

not virtuoso pieces, nor were they meant to be. But they were not intended for children,<br />

either. Rather, they express the gentle, understanding feelings of an adult observing the world<br />

of a child, linking the two worlds in an intimate relationship. A yearning for a then still unattainable<br />

domestic happiness might well have been the true inspiration of this collection.<br />

The first two pieces, Von fremden Ländern und Menschen and Kuriose Geschichte, may<br />

keep the listener puzzled as to the strange places and people depicted in the former and the<br />

nature of the story told in the latter. The composer offers not a program but a mood and<br />

invites us to follow his flights of imagination. Easier to identify is the merry game of chase<br />

(Blindman’s Bluff) that is the subject of Hasche-Mann and the touching vignette called<br />

Bittendes Kind with its truly inspired stroke of suspended ending. Following the gentle but<br />

irresistible hint of the child’s plea, Glückes genug brings relief with a feeling of joyous satisfaction.<br />

In Wichtige Begebenheit, an important event in the day of a child is set forth in a<br />

manner of mock seriousness.<br />

Träumerei is, of course, too well known to require comment, except that it takes on a<br />

special meaning of gentleness and innocence when heard in this context. Am Kamin pictures<br />

a feeling of quiet contentment that adults would wish to share with a child. The programmatic<br />

Ritter vom Steckenpferd is clearly illustrated in whimsical tempo, while Fast zu ernst<br />

(“Almost too Serious”) is a perfect title for something that music can express so much better<br />

than words. In Fürchtenmachen, childhood’s mysterious fears are captured in the alternating<br />

moods of the music. And then comes Kind im Einschlummern, its rocking, quiet melody that<br />

signals approaching sleep, and the suggestion of a concluding gentle sigh. Here the scenes of<br />

childhood come to an appropriate close, but enters the poet – Der Dichter spricht – who talks<br />

in plaintive tones, not so much to the sleeping child but to his listeners, creating a meaningful<br />

piano postlude for the set.<br />

Schumann, as a youth, lived in a never-changing atmosphere of feminine adulation. He<br />

– 7 –

made no secret of his affections, and published them in the dedications of his music, in thinly<br />

disguised musical acrostics, and in his letters. He examined and recorded the fluctuating<br />

states of his passion with cool detachment despite the depth of emotion. It seems that he<br />

lived in the third person singular, so analytical are his epistolary descriptions of his own feelings.<br />

He confided his loves to his mother, to whom he was deeply devoted. He often wrote<br />

to one of his feminine friends confessing admiration for another. And once he wrote to a perfect<br />

stranger, declaring in a curt sentence: “Clara Wieck loves, and is loved.” At that time he<br />

was going through the torturing battle of sentiment with Clara’s father who opposed<br />

Schumann’s marriage to Clara to the bitter end.<br />

Two other women besides Clara occupied Schumann’s mind during this early period of<br />

his life. One was Ernestine von Fricken, his first romantic love, the other, Henriette Voigt<br />

who played the role of a confidante. Ernestine was Estrella, the starlet of Schumann’s imaginary<br />

anti-Philistine Society of David. She was immortalized in the “dancing letters” of<br />

Carnaval, which spell the name of her native town. She was a pupilboarder at the house of<br />

Clara’s father, who never suspected that she and Schumann kept clandestine rendezvous at<br />

the house of Henriette Voigt, the confidante. The attitude of Captain von Fricken towards<br />

Ernestine was peculiar. He wrote her: “Play duets with Schumann, but be careful not to do<br />

anything that might disturb your peace of mind or harm your good name.” But when<br />

Schumann went to Asch, ready to sanction his relations by marriage, he found out to his dismay<br />

that Ernestine was an illegitimate child adopted by the Captain, and not an heir to his<br />

fortune. But the romance was already on the wane. Clara, although only sixteen, now occupied<br />

Schumann’s full attention. To make sure of the indivisibility of that attention, Clara<br />

wrote to Ernestine asking her whether she had any claims on Schumann, and received an<br />

admirably unselfish reply that she had none. Much later, analyzing his mental state in retrospect,<br />

Schumann wrote to Clara: “I feel strongly that Ernestine has been wronged. She was<br />

the victim of circumstances, and I know well that I was at fault.” But he found an explanation<br />

that mitigated his consciousness of guilt: Ernestine drove Clara from Schumann’s heart<br />

without being aware of it, and thus the priority of love was merely re-established when<br />

Schumann returned to Clara. Ernestine herself, strangely self-denying creature that she must<br />

have been, wrote to Schumann and told him she had always believed that he could love no<br />

one but Clara. Ernestine married an old aristocrat even before Schumann’s marriage to<br />

Clara; her husband soon died, and she followed him, a victim of a typhoid epidemic.<br />

Robert Schumann dedicated the Piano Sonata No.2 in G Minor, Opus 22 to Henriette<br />

– 8 –

Voigt, the accommodating confidante. Writing to Henriette in 1834, Schumann said she<br />

was “an A-flat major soul,” but her soul must have changed key, for the Sonata is in G<br />

Minor! Schumann was slow in composing this Sonata, and it took him nearly five years to<br />

bring it to completion. The Sonata is in the orthodox four movements, but each movement<br />

individually is far from orthodox. The first movement is feverishly impetuous. The tempo is<br />

marked “as fast as possible,” but towards the end of the movement there are further impellents,<br />

piu mosso, and ancora piu animato. The second movement is an uncommonly short,<br />

Andantino in 6/8, nominally in the key of C Major, but too fluctuating to convey a definite<br />

impression of tonality. Then follows a nervous, syncopated Scherzo, in the tonic key of G<br />

Minor. The last movement is a Rondo. The technical style is characteristic of the<br />

post-Beethoven period of piano literature. The accompanying figures contain wide intervals,<br />

awkward to play; there are elements or polyphony that suggest the mental image of an<br />

orchestra. Yet the Sonata is very pianistic, in the transcendental sense and pre-eminent<br />

among the works of the period as a highly successful composition expressing the new free<br />

and romantic spirit in a form inalienably identified with classical abstraction.<br />

– Notes by Marina and Victor Ledin, Copyright © 1990 and 2000<br />

– 9 –

The Artist<br />

“She knows what she is doing every minute of the time. It is amazing!”<br />

– Josef Hofmann after hearing <strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong><br />

in her New York debut at Town Hall, 1933<br />

<strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong> was born in Sacramento, California on January 15, 1925. From the<br />

time she was two years old, <strong>Ruth</strong>’s musicianship was evident to all. She was able to recognize<br />

and hum (in the correct keys!) themes by Beethoven, Bach and Mozart. By the age of three,<br />

she had mastered the rudiments of music theory and harmony. She began her studies with her<br />

father, a violin teacher in the San Francisco Bay Area, and gave her first public recital at the<br />

age of four, on May 10, 1929, at Mills College in Oakland. On Sunday, March 16, 1930, she<br />

gave a “farewell recital” at Erlanger’s Columbia Theatre in San Francisco. The program featured<br />

works by Bach, Mendelssohn, Grieg, C.P.E. Bach, Beethoven and Chopin. She was<br />

awarded a scholarship by Josef Hofmann to study at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia and<br />

this concert by the five-year-old was her last appearance before commencing studies.<br />

Hofmann taught her to lean into the piano keys on the soft part of her fingers in order to produce<br />

the desired sound. Although she received a few lessons from Hofmann, because of his<br />

busy concert schedule, she actually studied with Madame Isabelle Vengerova. Her older classmates<br />

were Shura Cherkassky, Jorge Bolet and Samuel Barber. Despite this brief foray into a<br />

conservatory, <strong>Ruth</strong>’s father, Josef Slenczynski, remained her primary teacher.<br />

Bay Area socialites, rallied by violinist Mischa Elman, raised money for <strong>Ruth</strong>’s study<br />

abroad under such masters as Egon Petri, Artur Schnabel, Alfred Cortot and Sergei<br />

Rachmaninov. When she was six, long lines formed around the historic Bachsaal in Berlin for<br />

her German debut. The cabled report to The New York Times declared her to be “the most<br />

astounding of all prodigies heard in recent years on either side of the ocean.” After her Berlin<br />

concert, the German critics mounted the stage to examine the full-sized piano on which the<br />

legs and pedal mechanisms had been shortened to enable her to play. They were seeking some<br />

sort of concealed mechanism or wires to account for the undersized six-year-old’s ability to<br />

produce the glorious sounds she had just drawn from the instrument. Apologizing for their<br />

disbelief, they departed just as dumbfounded as the rest of the frenzied audience.<br />

On the evening of November 13, 1933, the eight-year-old <strong>Ruth</strong> trotted confidently from<br />

– 10 –

the wings of New York’s Town<br />

Hall, poised herself on the very<br />

edge of her piano seat and propelled<br />

a pair of tiny hands through<br />

an almost unbelievable performance<br />

of masterpieces by Bach,<br />

Beethoven, Mendelssohn and<br />

Chopin. This was her New York<br />

debut. The next day, The New<br />

York Times declared the playing<br />

“an electrifying experience, full of<br />

the excitement and wonder of hearing<br />

what nature had produced in<br />

one of her most bounteous<br />

moods.” At nine she filled an entire<br />

cancelled tour of the immortal<br />

Ignacy Jan Paderewski; had her<br />

story serialized in 18 daily chapters<br />

syndicated to 500 leading<br />

American newspapers; swapped<br />

riddles with Herbert Hoover;<br />

received floral tributes from Queen<br />

Astrid of Belgium, Queen Marie of<br />

<strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong><br />

Romania, and King Christian X of<br />

Denmark; and earned more money than the President of the United States. Her musical<br />

career was to last another five years before she came to the heroic decision to withdraw from<br />

the concert stage.<br />

This was followed by a period of maturation, reassessment and personal growth. She<br />

worked at odd jobs to put herself through the University of California, Berkeley, where she<br />

earned a degree in psychology. She then served as professor of music at the College of Our<br />

Lady of Mercy in Burlingame, California. <strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong> returned to the concert stage at<br />

the Carmel Bach Festival in California in 1951. This appearance led to a performance with<br />

Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops in San Francisco. <strong>Ruth</strong> was then invited to play in<br />

– 11 –

Boston and was also asked to go<br />

on tour with the Boston Pops<br />

that following winter. The tour<br />

would require <strong>Ruth</strong> to perform<br />

with the orchestra for a threemonth<br />

period, performing every<br />

night, and twice-a-day on<br />

Saturdays and Sundays. The<br />

gruelling schedule would require<br />

that she travel every day by bus<br />

between concert venues.<br />

Nervous about forsaking her<br />

teaching position at the College<br />

of Our Lady of Mercy, she<br />

sought the advice of Artur<br />

Rubinstein in Los Angeles.<br />

Rubinstein encouraged <strong>Ruth</strong> to<br />

pursue the Boston Pops invitation.<br />

The first year of touring<br />

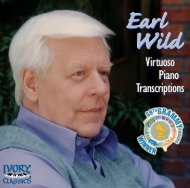

Earl Wild and <strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong>, 1999<br />

led to three more years with the<br />

Boston Pops. During that period she gave more than 360 performances with the orchestra –<br />

a record number of appearances by one artist with an orchestra! In 1956 she performed the<br />

Chopin F Minor Concerto with the New York Philharmonic conducted by Dimitri<br />

Mitropoulos at Carnegie Hall. Mitropoulos, who had conducted her appearance with the<br />

Minneapolis Orchestra when she was twelve, considered this 1956 engagement as the<br />

“discovery of a brilliant new artist on the threshold of a great career ahead.” He inscribed a<br />

photograph to her: “To a great pianist and musician.” In May of that year, some 35 million<br />

television viewers watched and listened with amazement as Ralph Edwards applied his<br />

unique “This Is Your Life” formula to <strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong>’s stranger-than-fiction real life story.<br />

Six months later it was set forth again, when the “best-of” “This Is Your Life” was highlighted<br />

on Arlene Francis’ coast-to-coast NBC “Home Show.” Also in 1956, her profile, sculptured<br />

by famed Malvina Hoffman, was designated as the symbol of achievement for the 1956<br />

Kimber Award in Instrumental Music of the San Francisco Foundation. Delta Omicron, the<br />

– 12 –

<strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> recording team after <strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong> recording sessions,<br />

October 1999. Edd Kolakowski, Ed Thompson, <strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong>,<br />

Michael Rolland Davis and Earl Wild<br />

International Music Fraternity<br />

founded in 1909, elected her to<br />

national honorary membership,<br />

conferring the title to a “musician<br />

who has attained outstanding<br />

recognition in the field of<br />

music.”<br />

In 1958, on the evening of<br />

November 13th, she returned to<br />

Town Hall to celebrate her<br />

Silver Jubilee. That same year<br />

she crossed the country, playing<br />

in 56 cities, in 20 different<br />

states, with appearances with six<br />

major symphony orchestras. In<br />

1961, when the San Francisco<br />

Symphony was celebrating its<br />

Golden Anniversary Season, she<br />

was invited to perform the<br />

Khachaturian piano concerto<br />

with the 25-year-old Seiji<br />

Ozawa conducting. She has performed<br />

more than 3000 recitals on both hemispheres and appeared with most of the world’s<br />

greatest orchestras. In 1984 she returned to New York’s Town Hall in celebration of over 50<br />

years on the concert stage. The New York Times critic, John Rockwell wrote: “unlike too<br />

many machine-tooled young virtuosos today, Miss <strong>Slenczynska</strong> brought an appealing lyricism<br />

and musicality to her interpretations... her technique remains a commanding one.”<br />

Although in 1985 she returned to the far eastern countries of Korea, Singapore, Thailand,<br />

Taiwan, Malaysia and the first visits to China and New Zealand, performing 115 concerts,<br />

she has pared back her concert schedule as follows: “Every three years I play internationally –<br />

between fifty and sixty concerts. Every year I play between twenty-five and thirty concerts<br />

and workshops all over the United States.” Although Ms. <strong>Slenczynska</strong> tried to retire from<br />

concertizing and teaching a couple of years ago, she has been unable to do so because of the<br />

– 13 –

constant demand for her concert performances and master classes. Today she still maintains<br />

an active teaching schedule at Southern Illinois University as well as conducting workshops<br />

and master classes around the country. <strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong> is married to retired political science<br />

professor James Richard Kerr and resides in Glen Carbon, Illinois. They are avid<br />

gardeners and dog lovers and collect art from all over the world. This recording marks <strong>Ruth</strong><br />

<strong>Slenczynska</strong>’s return to the recording studio after an absence of many years and continues<br />

<strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong>’ commitment to documenting her incredible musical career.<br />

Recordings by <strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong><br />

on <strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> ® :<br />

The Legacy of a Genius – <strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> 70802<br />

Bach: Italian Concerto; Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue,<br />

Toccata in C minor; and Sonata in D Major<br />

Chopin/Liszt: Six Chants Polonais, Op.74<br />

Liszt: Consolation No.1 in E Major; Hungarian Rhapsody No.15<br />

in A minor (“Rákóczy March”)<br />

<strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong> in Concert – <strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> 70902<br />

Haydn: Sonata No.47 in B minor<br />

Brahms: Rhapsody in B minor, Op.79, No.1<br />

Copland: Midsummer Nocturne (1947)<br />

Chopin: Sonata No.3 in B minor, Op.58<br />

Rachmaninov: Eight Preludes<br />

– 14 –

CREDITS<br />

l l l l l l l l<br />

Recorded at Fernleaf Abbey, Columbus, Ohio, October 5-7, 1999<br />

Original 24-Bit Master<br />

Producer: Michael Rolland Davis<br />

Recording Engineer: Ed Thompson<br />

Piano Technician: Edd Kolakowski<br />

Generous assistance came from the Michael Palm Foundation<br />

and <strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> Foundation<br />

Liner Notes: Marina and Victor Ledin<br />

Design: Communication Graphics<br />

Inside Tray Photo: <strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong><br />

Cover Photo: <strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong> in 1999<br />

(Photo by Michael Rolland Davis)<br />

To place an order or to be included on mailing list:<br />

<strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> ®<br />

P.O. Box 341068 • Columbus, Ohio 43234-1068<br />

Phone: 888-40-IVORY or 614-761-8709 • Fax: 614-761-9799<br />

e-mail@ivoryclassics.com • Website: http://www.<strong>Ivory</strong><strong>Classics</strong>.com<br />

– 15 –

1<br />

22<br />

35<br />

<strong>Ruth</strong> <strong>Slenczynska</strong><br />

Schumann<br />

Carnaval• Kinderszenen • Sonata No.2<br />

- 21 Carnaval (“Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes”), Opus 9 28:46<br />

- 34 Kinderszenen (“Scenes from Childhood”), Opus 15 18:15<br />

- 38 Sonata No.2 in G Minor, Opus 22 18:50<br />

Total Playing Time: 66:07<br />

Original 24-Bit Master<br />

Producer: Michael Rolland Davis • Engineer: Ed Thompson<br />

2000 <strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> ® • All Rights Reserved. 64405-71004 STEREO<br />

<strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> ® • P.O. Box 341068<br />

Columbus, Ohio 43234-1068 U.S.A.<br />

Phone: 888-40-IVORY or 614-761-8709 • Fax: 614-761-9799<br />

®<br />

e-mail@ivoryclassics.com • Website: www.<strong>Ivory</strong><strong>Classics</strong>.com