shura cherkassky - Ivory Classics

shura cherkassky - Ivory Classics

shura cherkassky - Ivory Classics

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

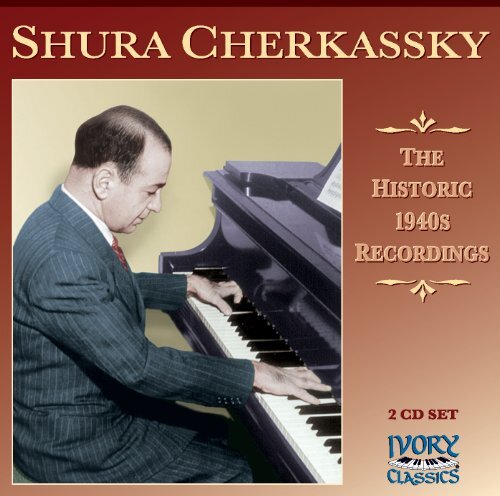

SHURA CHERKASSKY<br />

The Historic 1940s Recordings<br />

● ● ● ● ●<br />

Shura Cherkassky (1909-1995)<br />

Born in Odessa on October 17, 1909, * Shura Cherkassky was among the last of the post-Romantic tradition<br />

of master pianists. At the age of five he composed a five-act opera, and at ten he conducted a symphony<br />

orchestra. In 1922 he immigrated to the United States, where he met Harold Randolph, director of the<br />

Baltimore Conservatory. Randolph was so impressed by the boy’s talent that he arranged to have critics hear<br />

him perform. Astonished by Cherkassky’s prodigious talent, these critics arranged for the youngster to give a<br />

public recital at the Lyric Theater in Baltimore on March 3, 1923. Two other concerts, both to sold-out houses,<br />

followed, and a performance with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra in Chopin’s F minor concerto,<br />

launched Cherkassky’s career. His New York debut in November 1923 was pronounced by many critics as one<br />

of the most extraordinary musical events in recent memory. Olin Downes, in recalling that New York debut,<br />

spoke of the “delightful naturalness, ease, tonal beauty and sheer instinct of what was artistic” in the performance<br />

of the boy.<br />

Among the pianists who heard Cherkassky at that time were Ernest Hutcheson, Ignaz Friedman, Ignacy<br />

Jan Paderewski, Sergei Rachmaninov, Leopold Godowsky and Vladimir De Pachmann, who unanimously<br />

pronounced him an outstanding pianist. In 1924, Cherkassky was honored with a scholarship to the Curtis<br />

Institute in Philadelphia where he became a pupil of the renowned Josef Hofmann, himself a student of<br />

Anton Rubinstein. After his debut concert tour in 1923, Cherkassky appeared with Walter Damrosch and the<br />

New York Symphony, and was asked to give a command performance at The White House for President<br />

Warren G. Harding. Hofmann’s guidance strengthened and expanded the young pianists musicality, prompting<br />

Olin Downes to write after Cherkassky’s New York concert of December 14, 1926: “Shura Cherkassky is<br />

more than an imitative and facile young player, and more than an infant phenomenon of the not infrequent<br />

description. There is no question of his exceptional gifts.” Cherkassky was invited to play again at The White<br />

House, this time for President and Mrs. Herbert Hoover. In 1929, 1932 and again in 1935, Cherkassky<br />

undertook concert tours in Europe. In 1936 he undertook a world tour, revisiting Europe and including Asai,<br />

Australia, South Africa and the Soviet Union. Critics praised his “poetical playing” and “formidable virtuosity.”<br />

Shura Cherkassky’s enormous popularity in Germany and Austria, sprang from his first major European<br />

tour after the War in 1946, when a concert in Hamburg established him as one of the leading pianists of the<br />

*In many sources, Cherkassky’s birth year is listed as 1911. However, Ms. Christa Phelps of the Cherkassky Estate<br />

has confirmed that Cherkassky’s parents added two years to his actual birthdate in order to make his concert performances<br />

as a child prodigy more spectacular. The deception as to real birth year remained for the rest of his career.<br />

Mr. Cherkassky, in his last years, confided in Ms. Phelps that he was not born in 1911, but in 1909!<br />

– 2 –

Shura Cherkassky (January 14, 1946)<br />

– 3 –

day. During the 1940s, Cherkassky made his home in the Los<br />

Angeles area, where he lived on Sierra Bonita in the<br />

Hollywood Hills. He was a frequent contributor to the musical<br />

life of Los Angeles, appearing at the Hollywood Bowl, in<br />

Santa Monica, the Philharmonic Auditorium and the Wilshire<br />

Ebell Theater. The audiences and critics seem to have loved<br />

everything Cherkassky would perform. The reviews which<br />

appeared in the press were full of praise: “His keyboard<br />

prowess was fabulous, his command of every variety of touch<br />

— in chords, in passage work or in sustained melodic passages<br />

— was infinitely and uniquely varied, and in sheer sensuous<br />

beauty of sound his tone quality was unsurpassed.”<br />

Through a mutual friend, sculptress Malvina Hoffman,<br />

Cherkassky met Eugenie Blanc and they were married in<br />

1946. Mrs. Eugenie Blanc Cherkassky became Cherkassky’s<br />

promoter and manager, and managed the careers of a number<br />

of other prominent musicians as well, including Earl Wild.<br />

The marriage, however, lasted only a short time and ended in<br />

1948 in a somewhat public divorce. The Los Angeles Examiner<br />

wrote the following:<br />

She spent $27,000 to bring success to Shura Cherkassky, concert<br />

pianist, only to be discarded, Mrs. Eugenie Blanc Cherkassky<br />

Cherkassky (late 1920s)<br />

testified in court. “I owned a pharmacy which I sold for $27,000<br />

to pay for his musical education — but when the money was gone<br />

so was he,” she told Judge Thurmond Clarke, who granted her a divorce. Mrs. Cherkassky claimed her husband<br />

earned some $7,000 in one month in 1947, but gave her only $150 of the sum. Cherkassky did not contest her<br />

divorce plea, but a dispute arose over how much alimony the wife should get. The judge decided it should be over<br />

10 percent of his net earning for two years.<br />

When asked about his marriage in a 1990 interview, Cherkassky said: “It is difficult to be tied down to anyone<br />

when you play, unless the spouse is willing to be reduced to a servant. What does anyone get out of that?”<br />

Cherkassky’s acclaim only increased in the 1950s and 1960s. All over Europe Cherkassky had his following<br />

of enthusiastic admirers, from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean. He regularly performed at the prestigious<br />

music festivals of Europe, including those of London, Salzburg, Bergen, Zagreb, Carinthia and Vienna.<br />

As part of the 1955/56 season at the Hans Huber-Saal in Basel, Shura Cherkassky joined pianists Alexander<br />

Borowsky, Rudolf Firkusny, Yury Boukoff, and Stefan Askenase in a series of recitals presenting the entire<br />

piano works of Chopin. During this period he also collaborated with some of the world’s most distinguished<br />

conductors: Comissiona, Dorati, Giulini, Haitink, Karajan, Kempe, Leinsdorf, Ormandy, Shostakovich, Sir<br />

Adrian Boult, Sir Charles Groves and Sir Georg Solti.<br />

Shura Cherkassky’s concert career encompassed the entire musical world. In addition to Europe, he made<br />

several tours throughout the Far East, including China, Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand, and Japan. He also<br />

toured Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and India. His triumphant return to his native Russia in 1976<br />

– 4 –

had great emotional significance for him, and he was re-invited for subsequent tours in 1977 and 1979.<br />

Early in 1976 Shura Cherkassky returned to the United States after an absence of ten years. His New York<br />

recital was received with such resounding acclaim that he devoted an important part of each season to North<br />

America. An international artist might be expected to remain stationary during his holidays, but not<br />

Cherkassky. His passion for constant travel took him to Afghanistan, Thailand, Israel, Egypt, the Greek<br />

Islands, the African Coast, Northern Europe, the South Pacific, Latin and South America, Siberia and China.<br />

In 1990 he was asked whether his playing had undergone any dramatic changes. Cherkassky replied with candor:<br />

“Yes, I think so. I’m not as erratic as before. I used to be too free, with too many changes in dynamics<br />

and tempo, and now I try to curb myself. I’m also playing better.”<br />

Shura Cherkassky, died in London, on December 27, 1995. Writing in Gramophone, music critic and<br />

long-time friend, Bryce Morrison stated: “Few, if any pianists, have made music so entirely their own, coloring<br />

and projecting every bar and note with an instantly recognizable zest and brio. Rejoicing in spontaneity<br />

and listening askance to younger colleagues with set and inflexible ideas, he could turn a work — whether a<br />

Beethoven sonata, a Chopin Scherzo, a contemporary offering or a delectable trifle from a bygone age by<br />

Rebikov or Albéniz-Godowsky — this way and that, reflecting its contours and tints as if through some<br />

revolving prism... Musically speaking he was one life’s great adventurers, tirelessly seeking out novel angles,<br />

nooks and crannies, deploying a heaven-sent cantabile (“Nobody seems to care about sound any more,”<br />

Cherkassky once lamented) and, at his greatest, complementing his plethora of ideas with a rich and transcendental<br />

pianism.”<br />

Over his long career, Shura Cherkassky recorded for London/Decca, Nimbus, Vox, Deutsche<br />

Grammophon, L’Oiseau-Lyre, Reader’s Digest, HMV, Concert Hall Society, Cupol, Columbia, RCA Victor<br />

and Tudor. Cherkassky’s earliest recordings were made in the 1920s for Victor Records. In the 1930s he<br />

recorded with cellist Marcel Hubert, the premiere recording of Rachmaninov’s Cello Sonata, which received<br />

admiration and praise from the composer. In the 1940s he recorded for the Swedish label Cupol, for the<br />

American Vox label, and for HMV in England. It is his rarely heard recordings from the 1940s that are featured<br />

on this <strong>Ivory</strong> <strong>Classics</strong> ® release. Cherkassky’s 1982 San Francisco Recital is also available from <strong>Ivory</strong><br />

<strong>Classics</strong> ® 70904.<br />

● ● ● ● ●<br />

The Music and Recordings<br />

All of the performances heard on this two-CD set were recorded by Shura Cherkassky during the 1940s.<br />

This was a particularly active period for Cherkassky. He performed frequently in his home-base of Los Angeles<br />

and made numerous appearances in New York and most American music centers. After the war, Cherkassky<br />

made extensive tours of Europe and was a favorite in Scandinavia, where he recorded some of the discs included<br />

on this release. Because there are so many short compositions by many different composers on these two<br />

CDs, the notes on the music are organized alphabetically for ease of accessibility.<br />

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)<br />

Those who are fond of arranging and organizing things according to initial letters have called attention<br />

to the fact that the names of three great German masters of music begin with the letter “B”. In chronological<br />

– 5 –

as well as alphabetical succession they are: Bach, Beethoven, Brahms. The first is the master of polyphony and<br />

the fugue; the second of the monophonic style and sonata-form; the third was a master of a more modern<br />

contrapuntal construction and of the forms of his classical predecessor, at the same time showing unusual<br />

power to make the form fit the musical idea.<br />

Brahms wrote in practically every style of music, for orchestra, chamber music, large choral works, songs,<br />

and for the piano. He did not write for the dramatic stage, and but little for the organ. His highest opus number<br />

is 121. Many of these opuses contain several numbers and in addition there are numerous works without<br />

opus numbers. In all there are upwards of 500 separate compositions. Brahms was deeply interested in the<br />

technique of piano playing all his life, and he seems to have secured from the instrument the utmost fullness<br />

of effect. Many great artists agree that Brahms is an essential contributor to piano literature.<br />

“This month,” wrote Clara Schumann, “has introduced us to a wonderful person, Brahms, a composer<br />

from Hamburg, only twenty years of age... He played us sonatas, scherzos, and so on of his own, all of them<br />

showing exuberant imagination, depth of feeling, and mastery of form... He has studied with Marxsen, but<br />

what he played to us is so masterly that I feel that the good God sent him into the world ready made.” The<br />

latest of the works played by the young Brahms to Robert and Clara Schumann was the Sonata No.3 in F<br />

minor, Op.5 (DISC 1, 5 - 9 ) already his third essay in the form and indubitably the best of them. He had<br />

come armed with introductions from Joachim at Hanover and Wasielievsky at Bonn, to be absorbed immediately<br />

into the Schumann household and to become Clara’s life-long friend after Robert’s early breakdown<br />

and death. The new composer was boyish and impetuous, charming and earnest, a single-minded as well as<br />

gifted musician. The F minor Sonata is an astonishing production for an adolescent. It remains to this day one<br />

of Brahms’ most important works for solo piano, and whereas later the composer touched more intimate<br />

depths and expressed himself with greater control, he never showed a livelier or more brilliant flame of inspiration.<br />

The opening movement spaciously contrasts a turbulent figure. Its attendant tune is broad and sweet<br />

in melody. Out of them, in the middle section, Brahms distills a new melody in the bass. At the head of the<br />

andante a verse is quoted from a poem by Sternau — “twilight, and the moon shining, with two loving hearts<br />

in blissful unity.” The movement is a continuous outpouring of melodies, each giving rise to the next, until<br />

a large-scale climax-tune is treated in full voice. The scherzo is a torrent of youthful vigor and restlessness; even<br />

in the trio (marked only legato) the smoother subject only screens a smoldering fire, which readily breaks out<br />

again in the bridge-passage to the da capo section. The interpolated Intermezzo has caused commentators<br />

questioning speculations. The sub-title “Ruckblick” shows its intention — a sad reminiscence of what has<br />

gone before, especially the Andante melody reviewed through gloomy eyes. Is it more than the normal despairing<br />

mood that comes over any aspirant adolescent? The music is effective and the first and last movements<br />

are linked with uncommon skill. In the finale the agitated first subject is quieted for a time by a smoother<br />

and more ordinary subject; its real substance, however, lies in a new melody in D-flat, suddenly announced<br />

after the exposition, and destined to dominate the whole movement — indeed, the whole sonata.<br />

Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944)<br />

Cécile Louise Stéphanie Chaminade was born in Paris on August 8, 1857. She showed her musical talent<br />

at an early age and began to compose at the age of eight. Georges Bizet, upon seeing the first little works<br />

that the eight-year-old Cécile had written, affectionately called her mon petit Mozart and did what he could<br />

to assure that the promising prodigy was given solid musical training. Since at that time a number of classes at<br />

– 6 –

Cherkassky at Steinway headquarters in New York playing for musicians and critics, including<br />

Willem Mengelberg, Ernest Hutcheson and Ignaz Friedman (March 31, 1923)<br />

the Paris Conservatoire were prohibited to women students, Chaminade took private lessons in piano, violin<br />

and ensemble playing with Félix Le Couppey, Joseph Marsick, and Augustin Savard and composition with<br />

Benjamin Godard. Her one-act comic opera La Sevillane was heard at the Salle Erard in 1884, prompting<br />

composer and music critic Ambroise Thomas to write that she “is not a woman who composes, but a composer<br />

who is a woman.”<br />

She made her public debut as a pianist at the age of eighteen and in 1892 gave a command performance<br />

at Windsor Castle for Queen Victoria. Her many concert tours took her all over Europe, Greece, Turkey and,<br />

in the Autumn of 1908 she concertized in the United States and Canada. In 1913, Chaminade became the first<br />

woman composer to be inducted into the French Legion of Honor. During World War I she devoted herself<br />

to benevolent work and by 1922 her compositional activity receded increasingly into the background after she<br />

retired from social life in 1922. When she died in Monte Carlo on April 13, 1944, the musical world remembered<br />

her solely for her Concertino for Flute and Orchestra and a handful of piano pieces.<br />

She is best known today for her piano pieces and her many songs, which at one time enjoyed great popularity.<br />

Her more ambitious works include a Symphonie lyrique, entitled Les Amazones, for chorus and<br />

orchestra; a ballet, Callirhoë; a comic opera, La Sevillane; two orchestral suites; a Concertstück for piano and<br />

orchestra; the Concertino for Flute and Orchestra; and two trios for piano and strings.<br />

Chaminade left a large and wonderful body of piano works, including one sonata. The bulk of her<br />

piano compositions are miniatures, among which some of the most famous are the character pieces La<br />

– 7 –

Lisonjera (The Flatterer), Les Sylvains (The Fauns), Arlequine,<br />

Scarf Dance (Air de Ballet, No.3) and Pierrette. Autrefois<br />

(“From Olden Times”) (from Six Pièces humoristiques),<br />

Op.87, No.4 (DISC 1, 4 ) is an “homage” to the French<br />

clavecinistes of the past, Couperin and Rameau.<br />

Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849)<br />

Etymologically, “impromptu” means improvisation. Even if<br />

Chopin was dreaming at the piano over the themes of his<br />

impromptus, he worked them over on paper so well that the four<br />

pieces wed the first rush of inspiration to the perfection of purified<br />

writing. If Chopin had called the Impromptu No.2 in F<br />

sharp Major, Opus 36 (DISC 2, 16 ) a nocturne instead of an<br />

impromptu we would not be surprised. This cantilena, marked<br />

andantino, has nothing fleeting about it. Theodor Kullak wrote:<br />

“The dreamy song-like beginning; the immediate contrast with<br />

which the march enters; the fantastic retrogression to the afterwards<br />

varied theme; finally, the passage gently gliding away —<br />

with their expressive accompaniment — all these things bear the<br />

impress of an impromptu suggested by scenes from real life.”<br />

Chopin’s fourth and final impromptu, the Fantasie-Impromptu<br />

Cherkassky with Frederick R. Huber, in C-sharp minor, Opus 66 (DISC 2, 17 ) was composed in<br />

Municipal Director of Music for 1834 and only published posthumously in 1855. It is one of<br />

Baltimore (March 1923)<br />

Chopin’s most memorable compositions because of its intrinsic<br />

beauty and the effective running “commentary” that is kept up<br />

between the two themes. In 1918 the team of Harry Carroll and<br />

Joseph McCarthy used this endearing Chopin melody as the basis for their popular song, I’m Always Chasing<br />

Rainbows, which was featured in the Broadway musical Oh, Look!.<br />

The Fantasie in F minor, Opus 49 (1841) (DISC 2, 18 ) is the greatest of Chopin’s miscellaneous pieces<br />

and one of his most inspired works. The Fantasie begins in march time — not funereal but solemn, distant,<br />

muted — and proceeds to a more assertive motive uttered with the sound of a trumpet playing softly. Then<br />

comes one of those episodes with an air of improvisation that Chopin employs to move swiftly from one state<br />

of mind to another. He soon gets to the life of the subject with a theme of a somber color and its development<br />

toward a seductive, exalted phrase: light wins over darkness. Then he begins a noble, chivalric song,<br />

punctuated with “tied” pizzicatos in the left hand. Next, without returning to the music of the introduction,<br />

Chopin extemporizes on the other themes and ends with a meditative, collected, peaceful, and rather short<br />

lento sostenuto. This is a transported reprise of the first episode after the introduction. A fan of modulations<br />

then suddenly snaps closed on a plagal cadence.<br />

The Mazurka is a Polish national dance in three-four time, frequently with a syncopated accent. Chopin<br />

was the first to look upon it as an art form; and when he came out of the East to Paris, via Vienna and Munich,<br />

he startled his listeners with its exotic strains. Chopin composed over fifty of these Mazurkas. They contain, in<br />

– 8 –

miniature, the essence of his music. None of them is particularly long, and some are tiny sketches, but all are<br />

packed with the color, sentiment and masterly technique that made Chopin one of the greatest of the Romantic<br />

composers. It is here that he expressed his love for his native Poland; it is here that he put all of his ingenuity<br />

and skill. The Mazurkas are far from being direct translations of Polish dances. As Franz Liszt once stated:<br />

“While Chopin preserved the rhythm of the dance, he ennobled its melody and enlarged its proportions... and<br />

as a result coquetries, vanities, fantasies, vague emotions, passions, conquests, struggles upon which the safety<br />

or favors of others depend, all meet in this Chopinesque dance.” The short and beautiful Mazurka No. 23 in<br />

D Major, Op.33, No.3 (DISC 2, 15 ) was composed in 1837-8, and the Mazurka No.46 in C Major, Op.68,<br />

No.1 (DISC 2, 14 ) was composed in 1830 and published posthumously in 1855.<br />

Chopin’s first published composition, in 1817 at the age of eight, was a Polonaise, and in the next five<br />

years he followed that with three more. Altogether there are sixteen Polonaises for piano solo, although the<br />

standard collections usually contain only eleven, of which four are posthumous publications. In addition,<br />

there are the Grande Polonaise, Opus 22 with orchestra accompaniment, to which Chopin added an introductory<br />

unaccompanied Andante Spianato, and the Polonaise, Opus 3, for cello and piano. The polonaise is a<br />

Polish processional dance in 3/4 time, and moderate in tempo. Sir George Grove provided the following probable<br />

origin of the polonaise: “In 1573, Henry III of Anjou was elected to the Polish throne and in the following<br />

year held a great reception at Cracow, at which the wives of the nobles marched in procession, past<br />

the throne, to the sound of stately music. It is said that after this, whenever a foreign prince was elected to<br />

the throne, the same ceremony was repeated, and that out of this custom the polonaise has gradually developed<br />

as the opening dance at court festivities.” The Polonaise in A-flat Major, Opus 53 (1842) (DISC 2,<br />

13 ) gives us Chopin in his most majestic and glorious. Legend has it that Chopin, weakened by illness, was<br />

feverishly composing when suddenly he imagined that the walls of his room opened and there came riding in<br />

from the night a cavalcade of armored heroes and the ancient personages of his musical dream. So vivid was<br />

the hallucination that he fled from the room in terror and for several days could not be persuaded to return<br />

and resume work on this magnificent composition. Who knows whether the story is true or not, however, the<br />

music is definitely one of Chopin’s greatest works.<br />

“I have composed a study in my own manner,” wrote Chopin in October 1829, when he was nineteen.<br />

In his “own manner” meant that for the first time he had written an emotional and spontaneous piece of<br />

music under a general classification which offered no clue to its musical content. Between 1829 and 1834,<br />

Chopin composed two sets of études. Opus 10 was dedicated to his friend Franz Liszt; Opus 25, to Countess<br />

Marie d’Agoult, whose daughter, Cosima, later married Richard Wagner. Theodor Kullak calls the Étude in<br />

C-sharp minor, Op.10, No. 4 (DISC 2, 20 ) a “bravura study of velocity and lightness,” while and Étude in<br />

C minor (“Revolutionary”), Op.10, No.12 (DISC 2, 19 ), we are told by Chopin’s contemporaries, was a<br />

direct musical expression of the emotions aroused in the composer on hearing of the taking of Warsaw by the<br />

Russians in 1831. In Moritz Karasowski’s Life of Chopin, we read: “Grief, anxiety, and despair over the fate of<br />

his relatives and his dearly beloved father filled the measure of his sufferings. Under the influence of this mood<br />

he wrote this C minor étude; out of the mad and tempestuous storm of passages for the left hand, the melody<br />

rises aloft, now passionate and anon proudly majestic, until thrills of awe stream over the listener, and the<br />

image is evoked of Zeus hurling thunderbolts at the world.”<br />

– 9 –

Mikhail Glinka (1804-1857)<br />

Mikhail Glinka was the founder of Russian classical music. Summing up, as it were, the achievements<br />

of his predecessors — Russian composers of the late 18th and early 19th centuries — Glinka laid the foundations<br />

of the national style of Russian music. Glinka was born on June 1, 1804, in the village of<br />

Novospasskoye in the Smolensk province. He spent his childhood in the family estate amidst the picturesque<br />

nature of central Russia. When Glinka was thirteen his parents took him to St. Petersburg and entered him<br />

at the Boarding School for Children of the Nobility attached to the Chief Pedagogical Institute. At the<br />

Boarding School Glinka showed an aptitude for many subjects, but most of all he was interested in music.<br />

He used to spend hours improvising at the piano. Music became the sole aim of his life and he began taking<br />

lessons from the pianist, John Field. By the time of his graduation in 1822 Glinka was already the composer<br />

of several original works, including a set of Variations on a theme of Mozart.<br />

In 1830, the young composer made his first trip abroad. He visited cities in Germany and Switzerland<br />

and spent about three years in Italy. He spent countless hours attending operatic performances and studying<br />

Italian bel canto. But he felt out of place in Italy. “I could not sincerely be an Italian,” he wrote in his Memoirs<br />

in 1854. “A longing for my own country led me gradually to the idea of writing in a Russian manner.” In<br />

August of 1832 he left Italy for good, spending some time in Vienna, where he heard the orchestras of Strauss<br />

and Lanner. In October he travelled to Berlin, where for the next five months he occupied himself in the study<br />

of composition techniques under the distinguished teacher Siegfried Dehn. In 1834 the death of his father<br />

prompted Glinka to return to Russia. Back home, the idea of writing a Russian opera gave the composer no<br />

rest. “The main thing is to choose the right subject, so that it will be purely national,” Glinka wrote to his<br />

friends. The poet V.A. Zhukovsky suggested to Glinka that he write an opera on the events of 1612 connected<br />

with the campaign launched by the Polish aristocracy against Russia. The struggle against the Poles had<br />

acquired a national character. The enemy was routed by the Russian volunteer corps headed by Minin and<br />

Pozharsky. One of the most vivid episodes of the struggle was the feat of Ivan Susanin, a Kostroma peasant,<br />

who sacrificed his life in order to save his Motherland from the enemy. This patriot became the central character<br />

in Glinka’s opera, A Life for the Tsar. No sooner had A Life for the Tsar been produced than Glinka,<br />

prompted by the playwright Shakhovskoi, fastened upon Ruslan and Lyudmila as the subject of his next opera.<br />

It was produced in 1842.<br />

In 1844, Glinka went abroad again, this time to Spain, a country which had attracted him since childhood.<br />

On the way to Spain the composer visited Paris where he met Hector Berlioz. Glinka spent the next<br />

two years in Spain, studying the folk music of Spain and incorporating it in some of his orchestral works,<br />

including the popular Jota aragonesa (also known as the First Spanish Overture). Russian melodies with<br />

their simplicity and sincerity, however, still occupied the main place in Glinka’s creative work. He had<br />

long wishes to create a work that would integrate Russian folk tunes of different styles. The result was his<br />

tone poem, Kamarinskaya (1848). During the last years of his life Glinka travelled a great deal and often<br />

visited St. Petersburg for long stays. Talented younger composers would flock to his flat on the corner of<br />

Nevsky and Vladimirsky Prospekts. Dargomyzhsky, Serov and Balakirev came to show their work to their<br />

elder friend and teacher. Glinka’s health began to deteriorate rapidly and his doctor’s suggested a change<br />

of climate. In May of 1856 Glinka left for Berlin. The trip proved fatal, and on February 15, 1857,<br />

Mikhail Glinka died of a cold. Several months later the body of the great Russian composer was brought<br />

– 10 –

to St. Petersburg and buried in the cemetery of the Alexander<br />

Nevsky Monastery.<br />

During his short life, Glinka composed eight works for the<br />

stage, eleven orchestral works, some chamber music, numerous<br />

songs, and many short piano pieces. Among his piano compositions<br />

is the Tarantella in A minor (1843) (DISC 1, 5 ) which is<br />

based on the Russian song “Vo pole beryoza stoyala” (In the field<br />

there stood a Birch tree).<br />

Morton Gould (1913-1996)<br />

Morton Gould was a phenomenally talented composer,<br />

pianist, conductor, arranger and orchestrator. A prodigy who grew<br />

up writing music on his family’s kitchen table in New York, he<br />

eventually became one of the most influential and prolific<br />

American composers, writing in a wide variety of musical forms —<br />

from ballet to Broadway, classical orchestra works to film and television<br />

scores. The legacy he left has yet to be fully appreciated.<br />

Gould was born in Richmond Hill, Long Island, New York,<br />

on December 10, 1913. At the age of 4 he was playing the piano<br />

and composing; at 6 he had his first composition — a waltz called<br />

Just Six — published, and performed at The Academy of Music in<br />

Brooklyn. By the time he was 8 he was playing on New York radio<br />

station WOR broadcasts. Also, at eight, he auditioned for the<br />

renowned Frank Damrosch, then director of the Institute of Musical Arts, forerunner of The Juilliard School.<br />

Damrosch awarded the boy a scholarship. Subsequently he took piano lessons from Abby Whiteside and also<br />

studied composition and theory with Dr. Vincent Jones of New York University.<br />

Following the completion of his music studies, Gould earned his living in theater, vaudeville, and radio<br />

as solo pianist and member of a two-piano team. At 18 he became a staff musician at Radio City Music Hall<br />

and a year later he accepted a position with the National Broadcasting Company. Working seven days a week,<br />

he played piano, electric piano, or celesta depending on what was needed for the condensed versions of operas,<br />

the precision of the Rockettes, the juggling acts, the ballet, or anything else that might have been happening<br />

on stage. In 1934, at the age of 21, Gould began a long and fruitful association with radio as conductor of<br />

an orchestra for the WOR Mutual network. Radio provided both an outlet for his talents and a national<br />

showcase for his orchestral settings of popular music as well as many of his early original works. He quickly<br />

became a radio and recording favorite. The ability to bring the structural dimensions and technical resources<br />

of serious music to American popular idioms became Morton Gould’s compositional calling card. Stokowski<br />

became the first of countless famous conductors who championed Gould’s music. Others included Toscanini,<br />

Solti, Dorati, Wallenstein, Maazel, Fiedler, Monteux, Reiner, Golschmann, Comissiona, Mitropoulos,<br />

Ormandy, Iturbi, and Rodzinski!<br />

The 1940s proved to be even more productive for Gould. During this period he composed three of his<br />

four symphonies, the very popular Latin-American Symphonette (1941), Spirituals for Orchestra (1941), the<br />

– 11 –<br />

Mrs. Eugenie Blanc Cherkassky<br />

(January 1948)

Cowboy Rhapsody (1942), Interplay for Piano and Orchestra (originally titled “American Concertette”) (1943),<br />

Viola Concerto (1943), Fall River Legend (1947), Philharmonic Waltzes (1948), Minstrel Show (1946), and<br />

Holiday Music (1947). His brilliant orchestral adaptation of the famous American popular song by Patrick<br />

Gilmore, “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” also became Gould’s most popular and mostperformed<br />

work, American Salute.<br />

“Composing is my life blood,” said Morton Gould. “That is basically me, and although I have done many<br />

things in my life — conducting, playing piano, and so on — what is fundamental is my being a composer.”<br />

His music was commissioned by symphony orchestras throughout the United States, the Library of Congress,<br />

the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, the American Ballet Theatre, and the New York City Ballet.<br />

Gould integrated jazz, blues, gospel, and folk elements into his compositions, which bear his unequaled mastery<br />

of orchestration and imaginative formal structures. He passed away on 21 February 1996 while serving<br />

as artist-in-residence at the newly established Disney Institute in Orlando, Florida. Gould was one of the most<br />

vital advocates of American music, a great musical communicator who, with enormous mastery and élan, was<br />

able to achieve a synthesis between concert and popular music.<br />

Morton Gould’s Prelude and Toccata (DISC 2, 11 ) was composed in 1945 for José Iturbi, shortly after<br />

he composed and dedicated to Iturbi the Boogie Woogie Étude (1943) (DISC 2, 12 ). According to Gould:<br />

“I wrote Prelude and Toccata in the period when I was doing much broadcasting and guest conducting, and<br />

when I was composing a lot. I was writing music for the pianist José Iturbi during this period; for example<br />

Interplay was originally written under the title American Concertette for Iturbi. After writing the short Boogie<br />

Woogie Étude for Iturbi, it occurred to me to write a longer piece in a more extended form. This work became<br />

the Prelude and Toccata. The Toccata is, in a sense, a perpetual motion on a continual ostinato, a stylized boogie<br />

as it were — almost a minimalist piece. It stems from a period when I was utilizing popular and jazz vernacular<br />

in my concert music.”<br />

Aram Khachaturian (1903-1978)<br />

Aram Khachaturian is Armenia’s greatest composer. Ethnically, the land known as Armenia includes<br />

northeastern Turkey and a sizeable chunk of Iran in addition to the nation of Kazakhstan that became, in<br />

1922, a member of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. This entire region lays claim to one of the<br />

world’s oldest musical traditions. Her bards — the ashugs — were renowned even in the fifth century. To<br />

this day it remains essentially monodic, with only the sparest rhythmic accompaniment encumbering its<br />

flights of fancy. Crossroads of this milieu meet at Tiflis, between the Black and the Caspian seas. It was here<br />

that Aram Khachaturian was born on June 6, 1903. Though he showed an early interest in music, and particularly<br />

the folk songs and dances of his native land, it was not until later in life that he was able to receive<br />

adequate musical training. His father, a bookbinder, was too poor to pay for a musical education. Up until<br />

his twentieth year Khachaturian knew almost nothing about theory or the musical repertory. Khachaturian<br />

came to Moscow in the autumn of 1921. The city, as well as the whole country, was going through a grim<br />

period of economic dislocation. People had not enough to eat, houses were unheated, and more often than<br />

not the audiences kept their coats on in theaters and concert halls. Despite this, Moscow’s theaters were<br />

seething with activity. Khachaturian’s move to Moscow interrupted his studies at the Tbilisi Commercial<br />

School. He took a preparatory course at Moscow University, finished it in 1922, and in that same year was<br />

admitted to the Physics and Mathematics program at the University where he studied for almost three years.<br />

– 12 –

His friends kept urging him to apply himself more seriously to<br />

music and in the autumn of 1922 he decided to attend the<br />

Gnesin Music School. There he studied cello and performed<br />

in ensembles and in student concerts. Khachaturian graduated<br />

from the Gnesin School of Music in 1929 and, on the advice<br />

of Mikhail Gnesin, began to prepare for his entrance examinations<br />

at the Moscow Conservatory. He was admitted to the<br />

Conservatory in the autumn of 1929, and in 1930 began studies<br />

with Nikolai Miaskovsky. Miaskovsky watched the creative<br />

searchings of his new pupil with sympathy and interest. He<br />

believed in Khachaturian’s talent from the start and, treating<br />

his creative personality with singular tact, guided the young<br />

musician solicitously along the path of great art. He taught<br />

Khachaturian more than just the intricacies of composition.<br />

He fostered as well in his pupil a better understanding of literature,<br />

painting, and architecture. While in Miaskovsky’s<br />

class Khachaturian composed a sonata for violin and piano, a<br />

trio for piano, violin and clarinet, a dance suite for orchestra,<br />

two marches for brass band, and numerous arrangements of<br />

Armenian, Turkmenian, Tatar and Russian folk songs. It was<br />

in this class too that Khachaturian wrote his First Symphony,<br />

his diploma work for graduation. Other major works followed<br />

Cherkassky (1924)<br />

which extended and magnified Khachaturian’s importance as<br />

a composer. The Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, introduced<br />

by the composer in Moscow in 1937, became instantly popular in the Soviet Union. To this day it is one<br />

of Khachaturian’s most famous and frequently heard large works. The Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, in<br />

1940, the ballet Gayaneh, in 1942, both won the much-coveted Stalin Prize. The two orchestral suites<br />

which the composer prepared from Gayaneh have enjoyed considerable popularity. One of the numbers<br />

from the Suite No. 1 has been particularly successful — the “Sabre Dance.” The first time the Suite No.1<br />

was played in New York, the “Sabre Dance” aroused such a demonstration that it had to be repeated. It was<br />

largely through the appeal of this one dance that the Columbia recording of the first suite became (according<br />

to Billboard) the best-selling classical album soon after its release in the United States in 1947. “Sabre<br />

Dance” became a juke-box favorite and for many months assumed the status of a nation-wide popular<br />

“hit.” In 1943 Khachaturian composed his Second Symphony, which was followed in 1944 by the<br />

Masquerade Suite, in 1946 by the Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, and in 1947 by his Third Symphony.<br />

When he was in Rome on a concert tour in 1950, he began thinking about a ballet about Spartacus, the<br />

heroic leader of the insurgent gladiators. He was deeply impressed by the historical memorials he saw —<br />

those mute witnesses to the tragic events of the remote past. Again and again he returned to the majestic<br />

ruins of the Colosseum and the arena where the gory games of the gladiators were once held. These impressions,<br />

Khachaturian said, were very helpful to him when he was composing the music for the ballet Spartacus<br />

in Moscow, drawing mental pictures of life in ancient Rome and the struggle of the insurgent slaves led by<br />

– 13 –

Spartacus. Soviet audiences heard the Spartacus symphonic suite long before the ballet had its premiere at the<br />

Kirov Theater in Leningrad on December 27, 1956. The suite comprises separate dances from the ballet and<br />

extensive symphonic fragments, including the world famous Adagio. In the spring of 1959 Aram<br />

Khachaturian was awarded the Lenin Prize for his Spartacus. In the 1960s, Khachaturian composed a trio of<br />

Concert-Rhapsodies, for violin, cello and piano, and in the 1970s a trio of solo string sonatas, for violin, viola<br />

and cello. Throughout his life he composed some twenty-five film scores and several albums of children’s<br />

piano music. His wife, Nina Makarova (1908-1976) was also a composer. Aram Khachaturian died in<br />

Moscow on May 1, 1978.<br />

Khachaturian composed only seven concert works for solo piano, along with two suites of children’s<br />

music and one suite for two-pianos, four hands. The Toccata (1932) (DISC 2, 1 ) is the best known of his<br />

piano works. It contains folk-inspired elements, and a central section with echoes of Granados’ La Maja y el<br />

Ruiseñor, surrounded by motoric piano athleticism.<br />

Anatoly Liadov (1855-1914)<br />

Anatoly Liadov was born in St. Petersburg into a musical family. His father and grandfather were professional<br />

musicians. Liadov’s first lessons were from his father, followed, in 1870, by admission to the St.<br />

Petersburg Conservatory, where he initially studied piano and violin. Additionally, he studied counterpoint,<br />

and entered the composition class of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Liadov eventually joined the faculty of the<br />

Conservatory, teaching harmony, theory and composition. During the 1870s he collaborated with Borodin,<br />

Cui, Rimsky-Korsakov and Shcherbachov on a light-hearted set of variations dedicated to Liszt. By the 1880s<br />

he was closely linked to the Russian nationalist movement headed by Mili Balakirev. Liadov’s orchestral works<br />

show incredible imagination and resplendent musical coloring. Works such as The Enchanted Lake, Op.62,<br />

Kikimora, Op.63, and Baba-Yaga, Op.56 firmly place Liadov among the most colorful of Russian symphonists.<br />

Along with his colleagues, Balakirev and Lyapunov, Liadov collected and documented the folk-songs of<br />

various districts and peoples of Russia.<br />

As a piano composer, Liadov was primarily a miniaturist, producing countless beautiful preludes, mazurkas,<br />

bagatelles, and études. His most popular and most-recorded piano piece is his Music Box in A Major, Opus 32<br />

(DISC 2, 4 ) which he composed in 1893, and subtitled “valse-shutka” (waltz-jest). This delightful tonepicture<br />

preserves the tinkling ethereal sounds we are accustomed to associating with a toy music-box.<br />

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)<br />

Liszt conceived the Hungarian Rhapsodies, as a kind of collective national epic. He composed the first in<br />

1846 at the age of 35, and his last in 1885 at the age of 74. Most of his Hungarian Rhapsodies are in the<br />

sectional slow-fast form of the Gypsy dance known as the czardas. The Hungarian Rhapsodies remain popular<br />

today after almost one hundred and fifty years. However, if we were to follow their history we would find in<br />

them the same contradictions in origin and purpose, the same contrast between serious musicianship and virtuoso<br />

exhibitionism which made Liszt himself so fascinating. There is no doubt that Liszt was devoted to his<br />

country, but he was a Hungarian more by enthusiasm than through upbringing or ethnic heritage. He could<br />

barely speak the language, for Hungarian was third to German and French at home. He left his native<br />

province at the age of nine for the more cosmopolitan cities of Vienna and Paris. When he returned some<br />

two decades later he was an international hero in need of a national identity. This identity was achieved<br />

– 14 –

through the special musical language of the Hungarian<br />

Rhapsodies.<br />

In order to collect Gypsy tunes and absorb the strong flavor<br />

of their rhythms — the slow pride of the Lassan and the<br />

dervish rampage of the Friska — Liszt lived in Gypsy encampments.<br />

His first fifteen Hungarian Rhapsodies were published<br />

by 1854 (the remaining five were to come in his last years).<br />

Liszt also wrote and had printed, in German and Hungarian,<br />

a long book entitled The Gypsies and their Music in Hungary.<br />

As scholars have discovered later, Liszt was entirely wrong<br />

about the Gypsy origins of Hungarian music. Half a century<br />

later Bela Bartók and Zoltan Kodály, after diligently collecting<br />

thousands of unadorned Magyar folk tunes, showed that the<br />

Gypsy contribution was a style of playing, a process of inflection<br />

and instrumental arrangement rather than anything original<br />

in form. However, Hungarian Gypsy music, as it is now<br />

called, was the glory of the nation and Franz Liszt’s compositions<br />

spread its fame to the ends of the earth. Although Liszt’s<br />

efforts were not a particularly worthy study in ethnomusicology,<br />

his free-ranging fantasies (and the use in the title of the<br />

word “rhapsody”) were strokes of genius. In the Hungarian<br />

Rhapsodies, Liszt did much more than use the so-called<br />

czardas. He miraculously recreated on the piano the characteristics<br />

of a Gypsy band, with its string choirs, the sentimentally<br />

placed solo violin and the compellingly soft, percussive<br />

effect of the cimbalom, a kind of dulcimer.<br />

Hungarian Rhapsody No.5 in E minor (DISC 1, 12 ) (Published 1853; dedicated to Countess<br />

Szidónia Reviczky). According to musicologists, this rhapsody is a free arrangement of a Hungarian dance<br />

by József Kossovits (who was active around 1800). Heard by itself, this “Heroic” Elegy (Heroïde-Elégiaque<br />

is the printed subtitle) does not remind us of any of the other rhapsodies, in either style or feeling. Themes<br />

suggesting Chopin’s funeral march (trio) and the “Revolutionary” Étude make one wonder whether the<br />

subject of this elegy was actually Liszt’s beloved friend, who died in 1849.<br />

Hungarian Rhapsody No.6 in D flat Major (DISC 1, 13 ) (Published 1853; dedicated to Count Antal<br />

Apponyi). This rhapsody is a masterful arrangement of four Hungarian songs popular in Liszt’s time and<br />

opens with a march-like Tempo giusto in D flat and proceeds through a short and sprightly Presto to brilliant<br />

octave development. The Lassan which is its principal endearment is especially doleful. The text which goes<br />

with it in Gypsy lore translates roughly as follows: “My father is dead, my mother is dead, and I have no<br />

brothers and sisters, and all the money that I have left will just buy a rope to hang myself with.” Once again,<br />

a number of these themes appeared also in Liszt’s series of the Magyar Dallok.<br />

Hungarian Rhapsody No.11 in A minor (DISC 1, 14 ) (Published 1853; dedicated to Baron Ferenc<br />

Orczy). The cimbalom figurations yield a new play of sonorities in this surprisingly short rhapsody. Here<br />

– 15 –<br />

Cherkassky with Joseph Hoffmann<br />

(circa 1920s)

Liszt chooses intimacy rather than dazzle. Suggestions of stringed instruments can be heard in the Vivace assai.<br />

Hungarian Rhapsody No.15 in A minor (“Rákóczi March”) (Second Version; Published 1871) (DISC<br />

1, 15 ). This work is somewhat dubiously classified as a Hungarian Rhapsody. It is in actuality better known<br />

as the “Rákóczy March.” This same Rákóczy March was orchestrated by Berlioz and incorporated by him into<br />

his Damnation of Faust. The actual march was originally written by an obscure musician named Michael<br />

Barna, in honor of Prince Francis Rákóczy, the historic hero of Hungarian nationalism and fiery nobleman<br />

who led the revolt against Austria in the early 1700s. It has long since become the national march of Hungary<br />

and a symbol of freedom and national pride.<br />

The three Liebesträume, are impassioned love songs without words. Yet, they began their existence as<br />

songs with words. Liszt published them in 1850 with the title Drei Lieder für eine Tenor – oder Sopranstimme.<br />

The first two songs were settings of poems by Ludwig Uhland (1787-1862) and the third, to a poem by<br />

Ferdinand Freiligrath (1810-1876). Liszt provides the complete texts of the Uhland poems and the first four<br />

verses of the Freiligrath’s poem before the piano pieces. Liszt called his Liebesträume nocturnes (“Notturni” ),<br />

music full of warm evening colors.<br />

Liebesträum No.3 in A Flat Major (Disc 1, 10 ) is the most celebrated of the three works. It is a<br />

setting of Freiligrath’s romantic poem O lieb, so lang du lieben kannst! (“O love, as long as you can love”):<br />

O lieb, so lang du lieben kannst!<br />

O lieb, so lang du lieben magst!<br />

Die Stunde kommt, die Stunde kommt,<br />

Wo du an Gräbern stehst und klagst<br />

Und sorge, daß dein Herze glüht<br />

Und Liebe hegt und Liebe trägt,<br />

So lang ihm noch ein ander Herz<br />

In Liebe warm entgegen schlägt.<br />

Und wer dir seine Brust erschließt,<br />

O tu ihm, was du kannst, zu lieb!<br />

Und mach ihm jede Stunde froh,<br />

Und mach ihm keine Stunde trüb.<br />

Und hüte deine Zunge wohl!<br />

Bald ist ein hartes Wort entflohn.<br />

O gott, es war nicht bös gemeint;<br />

Fer Andre aber geht und weint.<br />

Oh love, as long as you can love!<br />

Oh love, as long as you may love!<br />

The hour will come, the hour will come<br />

When you stand by their graves and mourn.<br />

Be sure that your heart with ardour glows,<br />

Is full of love and cherishes love,<br />

As long as one other heart<br />

Beats with yours in tender love.<br />

If anyone opens his heart to you,<br />

Show him kindness whenever you can!<br />

And make his every hour happy<br />

And never give him one hour of sadness.<br />

And guard well your tongue!<br />

A cruel word is quickly said.<br />

Oh God, it was not meant to hurt;<br />

But the other one departs in grief.<br />

Twice in the course of this impassioned work the melody is interrupted by a brief interlude between the<br />

verses, as it would seem, giving us a fleeting glimpse of the summer night with its subtle perfumes and vague<br />

whisperings. The work closes with a passage of soft, sweet, restful harmonies, a sigh of content in the final<br />

– 16 –

fruition of love’s dream.<br />

The Concert Étude No.2 Gnomenreigen (“Dance of<br />

the Gnomes”) (S145/R6) (1862/3) (DISC 1, 11 ) is a sinister<br />

rondo demanding the utmost virtuosity. Liszt’s gnomes,<br />

cavorting by moonlight, are obviously inspired by demonic<br />

forces. Although Liszt marks one section of the piece giocoso<br />

(“joyous”), this is not humans laughing but rather monsters<br />

cackling. Throughout the piece there is supernatural malice<br />

in the air and an atmosphere of alarm. At the end, the creatures<br />

scurry across the keyboard and away, giving us a sense of<br />

relief that they are doing their dastardly deeds elsewhere!<br />

Nikolai Medtner (1880-1951)<br />

Nikolai Medtner was an important Russian pianist. He<br />

entered the Moscow Conservatory in 1892. There he studied<br />

with Paul Pabst, Vassily Safonov, Vassily Sapel’nikov, Anton<br />

Arensky and Sergei Taneyev. Following graduation in 1900<br />

with a gold medal, he entered the Anton Rubinstein Piano<br />

Competition in Vienna, and won still another trophy. With<br />

this brilliant record to his credit, he had no trouble securing<br />

engagements as a pianist, touring Russia and Germany as a<br />

virtuoso. In 1906-08 and 1914-21 he was a professor at the Cherkassky (early 1930s)<br />

Moscow Conservatory. The political turmoil in Russia was<br />

too much to bear, and Medtner (along with Rachmaninov and other musical colleagues) emigrated, first settling<br />

in Germany. He lived in France (1925-35) and eventually moved to England where he lived the<br />

remaining years of his life. In 1946, made possible by the financial support of Jaya Chamarajenda, the<br />

Maharajah of Mysore, the Medtner Society was formed. Medtner recorded a number of his songs, piano<br />

pieces and the three piano concertos, before passing away in 1951.<br />

Medtner has been described as a neo-classicist, whose reverence for formal purity was “unparalleled in<br />

contemporary music.” According to Oskar von Riesemann, “Medtner’s real originality lies in his handling<br />

of rhythm. In this respect he has command of such fertility of combinations and demonstrates such infinitely<br />

varied possibilities and inventions, as to give him a place apart in the literature of modern music.” All<br />

of his compositions are noble, passionate, lyrical and rich in imagination. He developed new musical forms<br />

— short stories, improvisations, fairy tales and dithyrambs. The textures are complex, with an abundance of<br />

counterpoint, cross-rhythms and unusual metrical groupings. The Fairy Tale (“Skazka”) in E minor,<br />

Opus 34, No.2 (DISC 2, 2 ) has as its epigraph a verse from a Tyutchev poem which Medtner also set as<br />

his last song, Opus 61, No.8: “We lost all that was once our own.” According to biographer Barrie Martyn,<br />

“Here a river, like life, sweeps relentlessly onwards. From the very first bar the rippling left-hand triplet<br />

accompaniment to the very Russian melody runs in ceaseless undulation throughout the entire piece, the<br />

flow interrupted only momentarily by two brief cadences and eventually lost from view in the very last bar.”<br />

– 17 –

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963)<br />

The brilliant French composer, Francis Poulenc was born on 7th January, 1899 in Paris into a wealthy<br />

family of pharmaceutical manufacturers. He once wrote: “During my childhood I had only one passion —<br />

to play the piano. When I was two years old my parents gave me a child’s piano...” Poulenc’s mother was his<br />

first teacher and by 1915 Francis decided to seriously study the piano and began lessons with the eccentric<br />

virtuoso, and family friend, Ricardo Viñes. It was Viñes who, about a year later, introduced Francis to the<br />

remarkable Erik Satie, and it was through Viñes that he came into contact with a composer of his own age,<br />

George Auric, who became his lifelong friend. Francis Poulenc quickly became an excellent pianist, a virtuoso<br />

with a highly personal technique. He often performed, chiefly his own compositions, both as soloist and<br />

accompanist.<br />

Poulenc’s earliest piano compositions date from 1917. After World War I, Poulenc returned to the study<br />

of music, although he remained in the French army until after the Armistice. He became a pupil of Charles<br />

Koechlin. Koechlin was an excellent teacher, who advised his pupils to avoid the exaggerations of romanticism<br />

without sacrificing depth of feeling. In 1919 the concert audiences heard his three Mouvements Perpetuels<br />

and Poulenc became a household name almost overnight. Around 1920 the critic Henri Collet grouped<br />

together Auric and Poulenc, plus Milhaud, Honegger, Durey and Tailleferre, as Les Six (“The French Six”).<br />

By 1926 Milhaud, Honegger and Poulenc were winning recognition for their individual activities, and Les Six<br />

eventually passed into history.<br />

The next several decades were fruitful for Poulenc, who created many of his finest works, including the<br />

Concert Champêtre, a Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra, the Mass in G Major, songs, chamber music<br />

and, of course, more piano pieces. During World War II, Poulenc was an active member of the French<br />

Resistance movement. Works from these years include the poignant Violin Sonata dedicated to the memory<br />

of Federico Garcia Lorca and the deeply moving, tragic choral work, Figure Humaine, for unaccompanied<br />

double chorus, based on a poem of Paul Éluard. In 1947 his opera-burlesque, Les Mamelles de Tirésias, was<br />

performed at the Opéra Comique. The audiences were both shocked and delighted by the intriguing tonguein-cheek<br />

score and the strange libretto by Claude Rostand, where a character changes his sex and another who<br />

gives birth to 40,000 babies! In 1957 he produced the opera Les Dialogues des Carmelites, which received its<br />

American premiere at the San Francisco Opera on 22nd September, 1957. In 1959 he produced La Voix<br />

Humaine, and in 1961 the six-part Gloria for chorus and orchestra. Francis Poulenc died suddenly at his home<br />

in Paris on 30th January, 1963.<br />

The Trois Pièces from 1928 were dedicated to Ricardo Viñes. Originally this opus was conceived as a set<br />

of three pastorales, composed in 1918. Poulenc retained the first Pastorale and combined it with two newlycomposed<br />

movements. One of the two new pieces, the Toccata (DISC 1, 3 ) is a bravura piece involving<br />

crossed hands, broken chord figures and oscillating melodies.<br />

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)<br />

Not many contemporary composers write music with such an unmistakable identity as that of Prokofiev.<br />

The mocking reeds, the mischievous leaps in the melody, the tart and often disjointed harmonies, the sudden<br />

fluctuation from the naive and the simple to the unexpected and the complex — these are but a few of the<br />

fingerprints that mark Prokofiev’s works.<br />

Born in 1891, he began studying music early with his mother, Reinhold Gliere and Sergei Taneyev. At<br />

– 18 –

Photo of Cherkassky (circa 1941)<br />

dedicated to Joseph Hoffman<br />

five he wrote his first piano pieces, and at eight a complete<br />

opera. In 1903 he entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory<br />

where he studied with Liadov, Rimsky-Korsakov and<br />

Tcherepnin, graduating with the highest honors seven years<br />

later. In the spring of 1918, Prokofiev left the Soviet Union to<br />

circle the world. It is said that when he applied for his visa, the<br />

People’s Commissar of Education said to him: “You are a revolutionary<br />

in music just as we are a revolutionary in life, and<br />

we ought to work together. But if you want to go, we will not<br />

stand in your way.” By way of Siberia, Japan, and Honolulu,<br />

Prokofiev came to the United States, arriving in August, 1918.<br />

He appeared as a pianist and as a composer. While in this<br />

country, he received a commission from the Chicago Opera<br />

Company to write an opera — The Love for Three Oranges. In<br />

1923 Prokofiev began a ten-year residence in Paris. During<br />

this period he established his world reputation as one of the<br />

most powerful, original, and provocative composers of our<br />

time. In 1932 he returned to the Soviet Union. During the<br />

remaining 21 years of his life he composed some of his best<br />

known music to the film Alexander Nevsky, the opera War and<br />

Peace, his Symphony No.5, Opus 100, and the symphonic<br />

fairy tale Peter and the Wolf.<br />

As a pianist, Prokofiev concertized all over the world. He<br />

recorded his Third Piano Concerto and many of his shorter<br />

piano pieces. Prokofiev was a pianist of impressive accomplishment<br />

and his mastery of the instrument, and close familiarity with its resources shows unmistakably in<br />

his wonderfully idiomatic music for the piano. In spite of this, however, he is not, in the strict sense of the<br />

term, an innovator of keyboard style and technique. He did not seem interested in exploration, so his piano<br />

music contributed little that was new to the vocabulary of the instrument, little that exploited hidden or<br />

neglected resources of keyboard color, tone, and effect. Instead, he utilized the piano as a sort of testing and<br />

proving ground for purely musical ideas. As an instrument of harmony and tonal blending, it provided him<br />

with the ideal medium through which to develop a personal art. In his piano music, we find what might be<br />

termed the “essential Prokofiev” — the essence of his musical thought, his basic musical vocabulary. There is<br />

a deep intimacy of utterance in most of the piano works. The characteristic qualities we find in the larger<br />

orchestral works — epic folklorism, eccentric whimsy, delicate melodicism — are all found expressed in close<br />

similarity of feeling and effect in them. Some of Prokofiev’s finest music is to be found here and especially in<br />

the nine sonatas, a series of works which traces quite clearly his growth as a composer and the various stylistic<br />

changes which occurred during his career.<br />

Prokofiev’s Four Pieces, Opus 4, is a startling set. Composed in 1908 and revised in 1910-12, it is indeed<br />

a set, for it traverses the emotional spectrum: evocation (Reminiscences), exaltation (Ardor), desperation<br />

(Despair), and inspiration (Temptation). The fourth and last piece, also known as Suggestion Diabolique<br />

– 19 –

(DISC 2, 3 ) is a frightening, berserk explosion, the quintessence of shock and fury, frenetic anger, the conclusion<br />

and resolution to the ostinato of dejection that precedes it. The universe expands, then implodes, and<br />

Prokofiev gives us his interpretation of the “Big Bang”.<br />

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)<br />

Rachmaninov is, after Tchaikovsky, the most performed and the most recorded of all Russian composers.<br />

His second and third piano concerti and his Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini for piano and orchestra are standard<br />

repertoire of concert pianists throughout the world and among the most popular classical show pieces<br />

ever created.<br />

Rachmaninov was, after Liszt, the greatest pianistic genius. His extraordinary aptitude at the keyboard was<br />

evidenced at a very early age. The music world should be grateful that Alexander Siloti auditioned<br />

Rachmaninov when he was a boy with a propensity to play hooky and go ice skating instead of attending his<br />

music lessons in St. Petersburg. On Siloti’s recommendation, the young Sergei was transferred to Moscow,<br />

where a skeptical music faculty gave the lad a formidable first assignment with a two-week deadline: Johannes<br />

Brahms’ Variations on a Theme by Handel. This homework, however, was not challenging enough, because in<br />

merely two days the tall teenager played the entire composition perfectly from memory to everyone’s amazement.<br />

And in 1892, the nineteen-year-old Rachmaninov graduated from the Moscow Conservatory with the<br />

Great Gold Medal, an honor bestowed only twice before in the Conservatory’s thirty year history. Alexander<br />

Scriabin, graduating the same year as Rachmaninov, was awarded only the Small Gold Medal. Another prominent<br />

pianist and composer, Nikolai Medtner, received the Great Gold Medal in 1900.<br />

The short piano piece Polka de W.R. (DISC 1, 2 ) was composed on March 11, 1911 on a theme by Sergei<br />

Rachmaninov’s father, Vasili. When it was published a few months later, the composer dedicated the work to<br />

Leopold Godowsky. Although most scores still list the title with a “w”, it should be called “Polka de V.R.”<br />

Vladimir Rebikov (1866-1920)<br />

Vladimir Ivanovich Rebikov was a Russian miniaturist. Many of his short piano pieces have been likened<br />

to those of Grieg, and the more experimental pieces of later years gave him the title of Russian’s finest impressionist.<br />

He wrote eleven stage works, liturgical music, numerous short piano pieces (many very experimental<br />

and far reaching), and “mélomimiques” for voice and piano. His most adventurous and celebrated pieces are<br />

his stage works called “musico-psychological dramas”, such as The Woman with the Dagger (1911), Narcissus<br />

(1913) and The Gentry’s Nest, Opus 55. His best known work is a fairy play, after Dostoyevsky, Andersen and<br />

Hauptmann, called Yolka (The Christmas Tree), Opus 21 which was produced in Moscow in 1903. The<br />

endearing little Waltz (DISC 2, 10 ) from this work is the stuff of Russian childhood memories.<br />

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921)<br />

When in 1881 Saint-Saëns was elected to the Institut de France someone said, “If it were necessary to<br />

characterize Saint-Saëns in a few words we should call him the best musician in France.” He was a man of<br />

extraordinary, and seemingly inexhaustible, energy and drive. He was an expert organist and pianist, teacher<br />

and founder of the Société Nationale de Musique. He edited the music of other composers, including a comprehensive<br />

edition of Rameau’s works, and wrote theoretical treatises on harmony and melody. Beyond all<br />

this he was an amateur astronomer, physicist, archaeologist, and natural historian. He painted, enjoyed<br />

– 20 –

learning new languages, was an omnivorous reader of the classics,<br />

and did creative writing. In short, Saint-Saëns was a man of<br />

immense culture.<br />

He was described by Georges Servières as “of short stature. His<br />

head was extremely original and the features characteristic: a great<br />

brow, wide and open where, between the eyebrows, the tenacity of<br />

the man reveals itself: hair habitually cut short, and brownish<br />

beard turning grey; a nose like an eagle’s beak, underlined by two<br />

deeply marked wrinkles starting from the nostrils; eyes a little<br />

prominent, very mobile, very expressive.”<br />

Saint-Saëns was a master craftsman who had an unerring<br />

musical sense and an astonishing ability to produce masterpiece<br />

after masterpiece. He left an astonishing volume of work including<br />

thirteen operas (of which Samson et Dalila is considered one of the<br />

greatest works of the French lyric stage), ten concertos (including<br />

the delightful Carnival of the Animals for two pianos and orchestra),<br />

seven symphonies, numerous choral works, over a hundred<br />

songs, symphonic poems, piano compositions and chamber<br />

Cherkassky (January 14, 1946)<br />

sonatas for violin, cello, clarinet, oboe and bassoon. He also wrote<br />

works for military band, cadenzas to piano concertos of Mozart<br />

and Beethoven, and transcribed and arranged numerous works by Bach, Gluck, Schumann, Mendelssohn,<br />

Berlioz, Mozart and others. “Of all composers, Saint-Saëns is most difficult to describe,” wrote Arthur Hervey.<br />

“He eludes you at every moment — the elements constituting his musical personality are so varied in their<br />

nature, yet they seem to blend in so remarkable a fashion... Saint-Saëns is a typical Frenchman... He is preeminently<br />

witty... It is this quality which has enabled him to attack the driest forms of art and render them<br />

bearable. There is nothing ponderous about him.” The Prelude and Fugue in F minor, Op.90, No.1 (DISC<br />

1, 1 ) is the opening piece of his Suite in F for piano, composed in 1891.<br />

Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915)<br />

Alexander Scriabin was a musical visionary, a genius, and an individualist with a strong, artistic voice. He<br />

was born in Moscow on 6 January, 1872, the son of an accomplished pianist. He began music studies early,<br />

entering the Moscow Conservatory in 1888. There he studied with Vasily Safonov, Sergei Taneyev and Anton<br />

Arensky (also Sergei Rachmaninov’s teacher). In 1892 the Moscow Conservatory awarded Scriabin their highest<br />

honor, a gold Medal (in piano playing). During this period he began composing exquisite piano miniatures<br />

which revealed such talent that they attracted the attention of the foremost publisher in Russia —<br />

Belaieff, who sponsored the young musician, gave him a handsome contract for his compositions, and subsidized<br />

a tour for him as piano virtuoso in programs of his own works.<br />

From 1898 to 1903, Scriabin taught piano at the Moscow Conservatory. But teaching proved a painful<br />

chore to him, and he abandoned it for composition and piano recitals. In 1906 he toured the United States<br />

with great success. During this time period his compositions were undergoing a radical metamorphosis,<br />

largely due to his increasing interest in mysticism and philosophy. In his Third Symphony, written in 1903,<br />

– 21 –

Cherkassky with actress Barbara<br />

Britton, rehearsing for their concert<br />

on May 26, 1949, at the Wilshire<br />

Ebell Theater in Los Angeles.<br />

subtitled The Divine Poem, he portrayed man’s escape from the<br />

shackles of religion and of his own past in ecstatic and triumphant<br />

music. His last two completed orchestral works were<br />

called Poem of Ecstasy, music which he said depicted the “ecstasy<br />

of unfettered action,” and Prometheus: The Poem of Fire. “For my<br />

part,” he once stated, “I prefer Prometheus or Satan, the prototype<br />

of revolt and individuality. Here I am my own master. I<br />

want truth, not salvation.” And in Prometheus: The Poem of Fire<br />

he described the omnipotence of the “creative will.” Scriabin<br />

died in Moscow on 27 April, 1915.<br />

During his short life of 43 years, Scriabin wrote three<br />

symphonies, two symphonic poems, variations for string quartet,<br />

a romance for French horn, a romance for voice, one piano concerto,<br />

and more than two hundred piano compositions. The<br />

Prelude for the Left Hand Alone in C-sharp minor, Op. 9,<br />

No.1 (DISC 2, 8 ) was conceived in the summer of 1891, when<br />

Scriabin spent a great deal of time practising, among other works,<br />

Liszt’s Don Juan Fantasy and Balakirev’s Islamey. Scriabin’s<br />

overzealous practising strained his right hand seriously, resulting<br />

in neuralgia. This caused the composer much anguish and for a<br />

time he feared having to give up permanently his career as pianist.<br />

The richly romantic piece for the left hand (along with its companion<br />

piece, the Nocturne) which Scriabin composed in 1894,<br />

shows influences of his twin musical references of that period in<br />

his life, Chopin and Liszt. Biographer Faubion Bowers calls the<br />

works “original, ostentatious and luscious.”<br />

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)<br />

Dmitri Shostakovich was born on September 25, 1906, in a house on the quiet Podolskaya Street in<br />

St. Petersburg, not far from the Institute of Technology. His parents came from Siberia and were both musical.<br />

His mother had played the piano from childhood and almost all her life had been a music teacher. The<br />

father was a dilettante in music; he was very fond of singing, especially the Gypsy songs that were popular<br />

in those days. On the occasion of his 50th birthday, Shostakovich provided the following autobiographical<br />

note: “I grew up in a musical family. My mother, Sophia Vasilyevna, studied for some years at the<br />

Conservatory and was a good pianist. My father, Dmitri Boleslavovich, was a great lover of music and sang<br />

well. There were many music-lovers among the friends and acquaintances of the family, all of whom took<br />

part in our musical evenings. I also remember the strains of music that came from a neighboring apartment<br />

where there lived an engineer who was an excellent cellist and was passionately fond of chamber music.<br />

With a group of his friends he often played quartets and trios by Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Borodin<br />

and Tchaikovsky. I used to go out into the corridor and sit there for hours, the better to hear the music.<br />

In our apartment too, we held amateur musical evenings. All this impressed itself on my musical<br />

– 22 –

memory and played a certain part in my future work as a composer.”<br />

Shostakovich was educated at Shidlovskaya’s Commercial School where he did well although he had some<br />

trouble with geography and history. At ten years of age he entered Glyaser’s School of Music in Petrograd. He<br />

studied there from 1916 to 1918, and in 1919 passed his entrance examination to the Petrograd<br />

Conservatory. There he studied with Leonid Nikolayev, becoming a world-class pianist. In a review published<br />

in 1923, the critic wrote: “A tremendous impression was created by the concert given by Dmitri Shostakovich,<br />

the young composer and pianist. He played Bach’s Organ Prelude and Fugue in A Minor in a transcription by<br />

Franz Liszt and Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata, along with several of his own piano compositions.<br />

Shostakovich played with a confidence and an artistic endeavor of great fluency that revealed in him a musician<br />

who has a profound feeling for the understanding of his art.” Shostakovich was only 17 years old at the<br />

time!<br />

Shostakovich finished his course of piano studies at the Conservatory in 1923. Four years later he took part<br />

in the First International Chopin Competition in Warsaw, where he was awarded a Certificate of Merit. But<br />

afterwards he decided to abandon the career of concert pianist. This is what he said about it: “After finishing<br />

the Conservatory I was confronted with the problem — should I become a pianist or a composer? The latter<br />

won. If the truth be told I should have been both, but it’s too late now to blame myself for making such a ruthless<br />

decision.” Shostakovich’s last concert as piano soloist was given in Rostov-on-Don in 1930. He rarely<br />

appeared on concert stages after that and only on occasions when he would perform his own compositions.<br />

Although he began composing at the age of ten, he did not seriously apply himself to composition until<br />

entering the Conservatory. There he enjoyed the fatherly patronage of Alexander Glazunov and studied vociferously<br />

under Maximilian Steinberg, a disciple and student of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Shostakovich’s first<br />

work that had crossed the dividing line between boyhood and manhood was the Scherzo in F sharp minor for<br />

orchestra which was published as his Opus 1 in 1919. What followed were Eight Preludes for Piano, Opus 2,<br />

Theme and Variations for Orchestra, Opus 3, Two Fables for Mezzo-Soprano and Orchestra, Opus 4, Three<br />

Fantastic Dances for Piano, Opus 5, a Suite for Two Pianos, Opus 6, another Scherzo for Orchestra, Opus 7, his<br />

First Piano Trio, Opus 8, Three Pieces for Cello and Piano, Opus 9, and the Symphony No.1 in F minor, Opus<br />

10.<br />

Shostakovich became an overnight sensation on May 12, 1926, when the Leningrad Philharmonic under<br />

Nikolai Malko gave the first performance of his First Symphony. The score was his graduation work,<br />