Exhibition Catalog - Lawrence Technological University

Exhibition Catalog - Lawrence Technological University

Exhibition Catalog - Lawrence Technological University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Lawrence</strong> <strong>Technological</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

Frank Lloyd Wright<br />

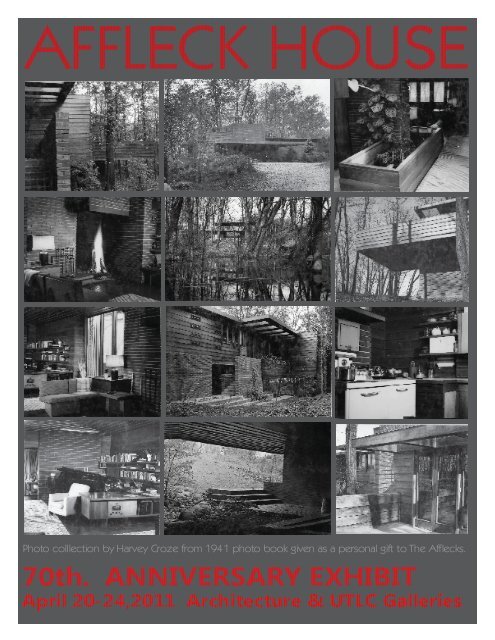

AFFLECK<br />

HOUSE<br />

70th Anniversary <strong>Exhibition</strong>

<strong>Exhibition</strong> <strong>Catalog</strong> April 20-24, 2011

Introduction<br />

The 70th construction anniversary of the Affl eck House offers an ideal opportunity to celebrate<br />

the genius of Frank Lloyd Wright and the commitment of the College of Architecture<br />

and Design at <strong>Lawrence</strong> <strong>Technological</strong> <strong>University</strong> to preserve its legacy. The Affl eck House<br />

provides our students with an environment in which to study in a “living laboratory” of mid-<br />

20th century architecture by an American master. Our students are inspired to produce artistic<br />

and technical projects, some of which are included in this catalog with many more in<br />

the exhibition. Since the Affl eck family has entrusted their house to us, College of Architecture<br />

and Design faculty, staff, and students have tirelessly contributed their time and talents<br />

toward the house’s care. It is with great pleasure that I present this catalog and exhibition in<br />

commemoration of the Affl eck House construction that has inspired exceptional student work<br />

and dedicated college efforts.<br />

i<br />

Glen LeRoy<br />

Dean, FAIA, FAICP, College of Architecture and Design<br />

<strong>Lawrence</strong> <strong>Technological</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

<strong>Lawrence</strong> <strong>Technological</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

21000 West Ten Mile Road<br />

Southfi eld, MI 48075<br />

Acknowledgments:<br />

This work is the production of the College of Architecture and Design (CoAD) at <strong>Lawrence</strong><br />

<strong>Technological</strong> <strong>University</strong>. Gretchen Maricak, editor and layout; Michelle Overley, graphic<br />

design, layout, and production; Anne Adamus, editor; Nik Prucnal, editor & layout. Joe<br />

Oberhauser and the Architecture Computing Resource Center (ACRC), printing. The CoAD<br />

Affl eck 70th Anniversary committee members: William Allen, Michelle Belt, George Charbeneau,<br />

Daniel Faoro, Jin Feng, Dr. Dale A Gyure, Gretchen Maricak, Brian Raymond, Steve<br />

Rost, Gretchen Rudy, Jolanta Skorupka, and Jim Stevens. Adrianne Aluzzo, the Architecture<br />

Resource Center, and Joe Oberhauser, ACRC, assisted in research for graphic production.<br />

Deans Glen LeRoy, Ralph Nelson, and Joe Veryser provided support and oversight.<br />

@ 2011 <strong>Lawrence</strong> <strong>Technological</strong> <strong>University</strong>. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced<br />

in any manner whatsoever without prior written permission from <strong>Lawrence</strong> <strong>Technological</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong>. The editor has attempted to trace and acknowledge all sources of images<br />

used in this booklet and apologizes for any errors or ommisions.

Contents<br />

Introduction from the Dean..................................................................................................................i<br />

Acknowledgments..............................................................................................................................i<br />

History of FLW Affl eck House by Dr. Dale Allen Gyure..........................................................................1<br />

Taliesin Blueprint Drawings..................................................................................................................29<br />

Taliesin Model and Drawings.............................................................................................................30<br />

Interior Design Study, Professor Jin Feng, Shawn Calvin.................................................................35<br />

Exterior Lamp Replica, Brian Raymond with Jason Westhouse.....................................................43<br />

Affl eck End Table Replica, by Brian Raymond with Jason Westhouse .......................................45<br />

Student Work<br />

Assistant Professor Jim Stevens with Lesa Rosmarek - Digital Fabrication.........................47<br />

Professor Steven Rost - Photography.....................................................................................49<br />

Professor Gretchen Maricak - Visual Communication 2......................................................53<br />

Professor William Allen - Allied Design.....................................................................................59<br />

Assistant Professor Janice Means - Affl eck Applied Study..................................................73<br />

Assistant Professor Michelle Belt - Furniture and Millwork.....................................................85<br />

Professor Steven Rost - Sculpture............................................................................................88<br />

Assistant Professor Jolanta Skorupka - Visual Communication 1, Independent Study.......90<br />

Assistant Professor Jolanta Skorupka - Visual Communication 1..........................................95<br />

Faculty Gallery<br />

Professor Gretchen Maricak.................................................................................................107<br />

Professor Steven Rost.............................................................................................................109

1<br />

History of Frank Lloyd<br />

Wright’s Affleck House<br />

Dr. Dale Allen Gyure<br />

Tucked away on a wooded knoll less than 100<br />

yards from a major eight-lane thoroughfare leading<br />

through Detroit’s northwest suburbs, the Gregor and<br />

Elizabeth Affleck house is a hidden gem from Frank<br />

Lloyd Wright’s early Usonian house period. The home<br />

captures everything that was best about Wright’s<br />

“organic” approach to architecture, and it served<br />

the Afflecks well for over three decades. Its history<br />

and design can tell us much about Wright’s architectural<br />

philosophy and the Afflecks’ unique tastes.<br />

The Afflecks<br />

The story of the house begins with Gregor Sidney Affleck,<br />

who was born in Chicago in 1893 and raised<br />

in Wisconsin. Little is known of his early life. His father’s<br />

family was from Muscoda, Wisconsin, about<br />

twenty miles west of Frank Lloyd Wright’s home<br />

territory. Gregor recalled that as a boy he lived in<br />

Spring Green, Wisconsin, across the river from where<br />

Wright’s family owned land and where Wright would<br />

build his own home “Taliesin.” Gregor “often visited<br />

the Hillside Home School” run by Wright’s aunts Jane<br />

and Ellen Lloyd-Jones, and he knew the Lloyd-Jones<br />

family (from Wright’s mother’s side). 1 A cousin of<br />

Gregor’s father was said to have worked at Taliesin<br />

as a secretary. Whether or not young Gregor had<br />

any other exposure to Wright is unknown.<br />

After graduating from Muscoda High School, Gregor<br />

enrolled at the <strong>University</strong> of Wisconsin to study chemical<br />

engineering. He joined the Navy ROTC program<br />

and the Chemical Engineer’s Society. Upon receiving<br />

his bachelor’s degree in 1918, Gregor briefly attended<br />

the Stevens Institute of Technology in New<br />

Jersey before heading to France at the end of World<br />

War I as an ensign in the Engineering Bureau of the<br />

Naval Reserve. 2 Then he drifted for a short period,<br />

briefly working for the Union Dye and Chemical Corporation<br />

in Kingsport, Tennessee and the French Battery<br />

Company of Madison, Wisconsin. 3 Eventually,<br />

like many other young professionals at the time, he<br />

was drawn to Detroit and the burgeoning automobile<br />

industry. By the early 1920s Gregor was working<br />

as a metallurgist for the Dodge Corporation in Detroit.<br />

A <strong>University</strong> of Wisconsin alumni magazine listed<br />

him as being “in charge of the physical testing laboratory<br />

of the Dodge Motor Co.” at the time.4 While<br />

there he met and fell in love with Elizabeth Besterci,<br />

a secretary for the Michigan Central Railroad who<br />

originally came from east central Pennsylvania. They<br />

were married on September 14, 1923; Gregor had<br />

just turned thirty and Elizabeth was almost twenty-two.<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze

Gregor, who once described himself as a “total survival<br />

of the Protestant work ethic,” became a successful<br />

chemical engineer.5 He obtained a number<br />

of patents, including one in Canada for a process<br />

for cleaning paint spray booths and another in the<br />

United States for a method for recovering residual<br />

coating materials from the walls and air of spray<br />

chambers. He would later establish and operate<br />

the Colloidal Paint Products Company in Detroit, a<br />

chemical business for auto products and cosmetics.<br />

These endeavors earned Gregor a healthy income;<br />

as he later admitted, he had “discovered how to<br />

make money.” 6 In his spare time he pursued an interest<br />

in photography. Elizabeth enjoyed gardening<br />

and sewing and stayed at home to raise their son,<br />

Gregor Peter Affleck, born in 1925. By the late thirties<br />

the couple had purchased a Colonial Revival-styled<br />

home in Pleasant Ridge in the Detroit suburbs.<br />

2<br />

Photograph by Anon.<br />

Frank Lloyd Wright in 1940<br />

When the Afflecks first contacted Frank Lloyd Wright<br />

about designing a house in 1939, the architect was<br />

enjoying a professional renaissance at the ripe age<br />

of seventy-two. After extremely rough years in the<br />

late twenties and early thirties, things had begun<br />

to change for Wright in 1932. The Depression and<br />

changing tastes in architecture had hit him hard. In<br />

the previous six years he had been able to construct<br />

only seven projects, and two of those were for himself<br />

and one for a cousin. An important architectural<br />

exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York,<br />

which gave birth to the phrase “International Style,”<br />

depicted Wright as a “half-modern” architect and<br />

an “individualist” whose inventive period had long<br />

passed. He had taken to writing and lecturing to support<br />

himself, while many believed him to have retired<br />

– or worse. “I have been reading my obituaries to a<br />

considerable extent over the past year or two, and<br />

think, with Mark Twain, the reports of my death greatly<br />

exaggerated,” Wright once wrote. 7<br />

But in 1932 a series of events occurred which would<br />

stimulate Wright’s architectural renewal. First, Wright<br />

founded the Taliesin Fellowship at Spring Green, Wisconsin,<br />

to train young architects in his philosophy of<br />

organic architecture and to provide a steady means<br />

of income through tuition payments. Despite the<br />

hard times Wright retained a certain amount of respect<br />

in the architectural world and had no trouble<br />

attracting students. The Taliesin Fellowship proved to<br />

be a key factor in the revitalization of Wright’s career<br />

by providing him with an inspiring atmosphere, similar<br />

to his Oak Park, Illinois, office in the early 1900s, where<br />

many of the Prairie School architects trained.<br />

Drawing by Taliesin, Photographs by Anon.<br />

Wright further established himself in the public eye with<br />

two books in 1932. The first was An Autobiography,<br />

which has been perceptively described as “a difficult,

evealing, inaccurate, but compelling book” about<br />

Wright’s life and philosophy. 8 An Autobiography was<br />

reviewed and praised in many leading journals. The<br />

second book, The Disappearing City, was Wright’s tirade<br />

against urbanization; it contained his first discussion<br />

of Broadacre City, the agrarian utopia that he<br />

intended as the replacement for the modern city.<br />

3<br />

In the next five years, Wright reemerged on the national<br />

architectural scene with such renowned designs<br />

as the Kaufmann “Fallingwater” House (1935),<br />

the Jacobs House (1936), the Johnson Wax Administration<br />

Building (1936), and his second home, Taliesin<br />

West (1937). His star shone brighter than ever, and<br />

more commissions began to arrive at Taliesin. Wright<br />

appeared on the cover of Time in January, 1938,<br />

and in nearly thirty articles during that year, from<br />

such popular fare as Life and The New Yorker to a remarkable<br />

special issue of Architectural Forum (also in<br />

January) devoted entirely to his architecture. 9 And<br />

the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened an<br />

exhibition on Fallingwater in January, the first time<br />

that institution ever held a major one-building exhibit<br />

on a living architect. Wright would continue to work<br />

on a seemingly endless stream of compositions until<br />

his death in 1959 at the age of ninety-one.<br />

Usonian Houses<br />

The major project of the last two decades of Frank<br />

Lloyd Wright’s life was the creation and promotion<br />

of “Usonian” houses. Wright conceived the Usonian<br />

project as an extension of the principles first developed<br />

in his Prairie-style houses of the 1900s-1910s.<br />

“Usonia” was a word coined by Wright to represent<br />

“The United States of America” – inspired by his perception<br />

that the moniker “America” was too vague,<br />

arguably including countries beyond the U.S.A. His<br />

intention was to build on the basic elements of the<br />

Prairie houses – natural materials, harmony with nature,<br />

open plans, and a uniquely American idiom<br />

– by utilizing mass production technology to produce<br />

affordable single-family housing for all socioeconomic<br />

classes. The Usonians would achieve their<br />

inexpensiveness through prefabricated parts, paring<br />

the house down to basics, and using a new method<br />

for constructing walls. Conceived as an antidote to<br />

the social and economic realities of the Great Depression,<br />

eighteen Usonian houses were built between<br />

1939 and 1941; the Usonian program eventually<br />

produced over 100 houses before Wright’s death<br />

in 1959.<br />

Wright was not alone in turning to mass production as<br />

a means to stimulate housing construction during the<br />

Depression. Although prefabricated housing dates<br />

back to the nineteenth century, conditions in Europe<br />

after World War I, and around the world in the thirties,<br />

drove architects of all persuasions to tackle the<br />

challenge of designing cost-efficient houses, leading<br />

Photograph by Balthazar Korab

some to experiment with unusual materials and factory<br />

procedures. Many realized that industrial practices<br />

like the use of standardized parts, preassembled<br />

pieces, and simple construction systems could<br />

significantly reduce costs. Wright was actually an<br />

early proponent of a type of prefabrication with his<br />

American System-Built houses of the 1910s. For Wright<br />

and others involved with such explorations, the most<br />

important issue was how to maintain quality, to keep<br />

the homes from becoming cheap, repetitious minimalist<br />

boxes. 10<br />

4<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Wright found a solution with the Usonians. Although<br />

the Usonian houses would come in a variety of<br />

shapes and sizes over the years, they all shared common<br />

features. First of all, they were placed directly<br />

on the ground. Wright did not believe in basements,<br />

and preferred to rest his houses – even back in the<br />

Prairie School days – on a concrete slab. For the Usonians<br />

he employed the slab not only as a base for<br />

the house, but also as the bed for a radiant heating<br />

system. Pipes enclosed in the concrete circulated<br />

hot water; the pipes transferred their heat to<br />

the surrounding concrete, which warmed the air at<br />

floor level, which in turn radiated upward through<br />

the house. As a result, the Usonians did not require air<br />

ducts, radiators, or dropped ceilings since the entire<br />

system was contained within the floor. Wright did not<br />

invent the ancient practice of radiant heating but<br />

did popularize it as a low-cost alternative to forced<br />

air systems.<br />

Wright also abhorred garages. Like basements, he<br />

felt they accumulated unnecessary clutter and<br />

could be avoided. So he designed the Usonians with<br />

carports instead of garages. Flat roofs, which could<br />

be built with less difficulty than standard pitched<br />

roofs, eliminated the need for “ugly” gutters, and<br />

emphasized the horizontal appearance that Wright<br />

favored. The Usonian houses were planned using a<br />

grid system which allowed contractors working without<br />

supervision from Taliesin to easily construct the<br />

house and imposed an order and uniformity on the<br />

whole. These decisions, along with the rejection of<br />

the basement, led to a house that was simpler to<br />

build. And simplicity was the key to the Usonians –<br />

not just in design and construction, but also in the occupants’<br />

anticipated lifestyle. “That house must be<br />

a new pattern for more simplified and, at the same<br />

time, more gracious living; necessarily new, but suitable<br />

to living conditions as they might so well be in<br />

this country we live in today,” Wright announced in<br />

1943. 11<br />

One of Wright’s most unique Usonian innovations<br />

came in the form of a new type of wall. He invented<br />

a sandwiched panel wall consisting of identical<br />

board and batten siding on the interior and exterior<br />

enclosing a core of plywood covered by tar paper.

5<br />

The modular wall sections could be prefabricated<br />

offsite and raised into place. Along with these panels,<br />

Wright discarded the traditional stud-wall frame.<br />

In the Usonians the weight of the roof instead rested<br />

on the sandwich walls, masonry (usually brick) end<br />

walls, and a masonry core at the center of the house<br />

containing the fireplace, kitchen, and utility room.<br />

Because the walls were relatively weak most Usonians<br />

were limited to one story in height, but Wright<br />

believed this to be a way to inject informality into<br />

these largely middle class houses, as well as helping<br />

to integrate the structure into the surrounding<br />

landscape. These sandwich walls contained no air<br />

cavities, so no wiring or piping could be run through<br />

them, as Wright felt them unnecessary because of<br />

the in-floor heating system.<br />

In keeping with the overall simplicity of the Usonian<br />

project, the houses required few materials beyond<br />

the concrete slab floor, wood, brick, and glass.<br />

These materials, Wright felt, needed very little maintenance,<br />

unlike the plaster, paint, and wallpaper<br />

of traditional houses. And the Usonians’ floor plans<br />

further revealed Wright’s desire to simplify as well as<br />

his recognition of social changes in American family<br />

life occurring by the 1930s. Economic necessities<br />

of the Great Depression and changing social mores<br />

led American families to seek greater informality and<br />

casualness in their lives. According to historian John<br />

Sergeant, “In America immediately after the war the<br />

new house was changing for three reasons: (1) there<br />

emerged a freer attitude toward children; (2) there<br />

was a new woman’s role with more activity outside<br />

the home; and (3) with a proliferation of external functions,<br />

less time was spent in the home.” 12 In response<br />

to the increasing amount of servant-less families and<br />

the emerging trend toward informality, Wright created<br />

houses more tailored to the demands of contemporary<br />

wife/mother roles. Most prominently, he<br />

abolished formal dining rooms in favor of alcoves<br />

with dining tables, which were located next to the<br />

kitchen – which he now called the “workspace” – in<br />

order to minimize the distance between the places<br />

for preparing and eating meals. He also collapsed<br />

together the dining and living areas. This essentially<br />

merged three rooms into one (counting the kitchen),<br />

continuing the process of opening interior space by<br />

breaking down boundaries that he had begun with<br />

the Prairie School houses.<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Usonian houses were “zoned” into public and private<br />

sections, and this can be read in their form and configuration.<br />

Many of these houses used an “L” shaped<br />

plan, or some variation, which placed the living/dining<br />

room in one wing, the bedrooms along a singleloaded<br />

corridor in the other wing, and the utility areas<br />

like the workspace and bathroom in the hinge<br />

between the two wings. This arrangement shielded<br />

the house’s private rooms from non-family visitors.

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Wright also saw the plan as cost effective because<br />

it could center all of the plumbing and most of the<br />

masonry into the utility core at the house’s center.<br />

Finally, the Usonians exemplified Wright’s longstanding<br />

dedication to an architecture that existed<br />

in harmony with nature. One of his most cherished<br />

principles, fully implemented in the Usonians, was<br />

that a building should seem to be of the land rather<br />

than on it. His houses emerged from the slope of a hill<br />

rather than sitting on top of it, which was the traditional<br />

method. He utilized wood as much as possible,<br />

inside and out, to evoke continuity with the natural<br />

landscape. He oriented the houses so that the living<br />

room faced southeast to guarantee abundant<br />

sunlight throughout the year. “Proper orientation of<br />

the house, then, is the first condition of the lighting of<br />

the house,” he once wrote. “The sun is the great luminary<br />

of all life. It should serve as such in the building<br />

of the house.” 13 To capture the sun’s rays, Wright’s living<br />

rooms featured floor-to-ceiling French doors that<br />

opened to a patio or balcony and dissolved the barrier<br />

between the interior and exterior. The doors also<br />

served as a shield against the elements while preserving<br />

views to the surrounding landscape. When<br />

opened, they emphasized the union between manmade<br />

object and its setting.<br />

The house’s relation with the natural landscape was<br />

crucial, not just for the sylvan atmosphere and picturesque<br />

views such a sensitive siting might provide, but<br />

also for Wright’s endeavor to change Americans’ living<br />

habits. He drew no distinction between the inside<br />

of the house and the outside, and felt both were united<br />

in one continuous designed space. According to<br />

Wright, “In integral architecture the room-space itself<br />

must come through. . . We have no longer an outside<br />

and an inside as two separate things. Now the outside<br />

may come inside, and the inside may and does<br />

go outside. They are of each other.” 14 Eliminating<br />

physical and psychological boundaries in this manner<br />

facilitated the occupants’ close relationship with<br />

nature.<br />

Another design element Wright employed to link<br />

people to the natural world involved the rejection of<br />

mechanical climate controls. As mentioned above,<br />

Wright used radiant heating from the floor rather than<br />

forced air systems in the Usonians; he also designed<br />

them without air conditioning. Wright believed artificially<br />

controlled climates removed humans one more<br />

step from direct contact with nature. “To me air conditioning<br />

is a dangerous circumstance. . . I think it is far<br />

better to go with the natural climate than to try to fix<br />

a special artificial climate of your own,” wrote Wright.<br />

“Climate means something to man. It means something<br />

in relation to one’s life in it.” 15 The houses all featured<br />

wall openings, such as French doors, windows,<br />

and clerestories, on all sides of the house, allowing<br />

6

cross-ventilation. Combined with sensitive siting and<br />

abundant natural growth around the houses, these<br />

features allowed Usonian occupants to keep comfortable<br />

even on the hottest summer days.<br />

7<br />

Initial Contact<br />

How the Afflecks came to desire a Frank Lloyd Wright<br />

home is open to speculation. The couple visited<br />

Taliesin as early as 1924, according to Gregor’s recollections,<br />

and both he and Elizabeth were impressed.<br />

But it was not until sometime in the late 1930s that<br />

Gregor and Elizabeth Affleck apparently encountered<br />

some drawings or photographs of Wright’s Fallingwater<br />

house in Pennsylvania, and were intrigued.<br />

They proposed to contact Wright to see if he would<br />

design a house for them. In September 1939, they<br />

made another trip to Taliesin.<br />

The Afflecks were the perfect kind of clients for Wright.<br />

He particularly attracted younger and progressively<br />

minded couples who had strong opinions, an interest<br />

in nature, and a disdain for the more formalized living<br />

conditions of earlier generations. 16 Gregor seems to<br />

have been the driving force behind the Afflecks’ decision.<br />

Their daughter, Mary Ann, later described her<br />

father as a “rather eccentric” man who wanted an<br />

“unusual home,” while her mother was remembered<br />

as having “more conventional tastes.” 17 In contrast<br />

to Gregor’s enthusiasm over the possibility of owning<br />

a Wright-designed home, evidence indicates Elizabeth<br />

was hesitant. “We may have some diffuculty<br />

[sic] with Mrs. Affleck but so far as I am concerned,”<br />

Gregor told Wright, “you can be as inventive as you<br />

have a mind to be.” 18<br />

During the Taliesin visit in 1939, Wright told the Afflecks<br />

to begin by buying some property in the country –<br />

“one or two acres of land, something with a little<br />

character to it, something nobody else can do anything<br />

with,” and preferably near some water. 19 The<br />

Afflecks then searched for almost a year before finding<br />

what they thought was the perfect place in the<br />

“wilds” of Bloomfield Hills, just north of Birmingham<br />

and the famous Cranbrook properties and about<br />

twenty miles northwest of downtown Detroit. The site<br />

was just over two acres in size and heavily-wooded,<br />

with a small slope running down to a ravine containing<br />

a pond between the house and Woodward<br />

Avenue, the extension of Detroit’s main thoroughfare<br />

that connected the city with Pontiac. The land<br />

dropped approximately twenty-five feet from the<br />

hillside where the house would be built to the water<br />

below. Gregor later described the lot as “a little valley<br />

completely covered with tall trees and with no<br />

level land at all.” 20<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Photograph by Anon.<br />

On May 30, 1940, Gregor sent a letter to Wright officially<br />

asking him to design their home. Wright’s response<br />

to Affleck’s initial photographs and sketches

of the proposed location was positive. “You certainly<br />

have made good and given us the kind of<br />

opportunity we like,” he wrote. 21 Almost three<br />

weeks later Gregor forwarded a list of the couple’s<br />

extensive requirements for their house:<br />

The equivalent of three bed rooms and maids quarters,<br />

(one maid).<br />

A large living room with large fireplace.<br />

8<br />

Utility room for laundry and possible use as a laboratory<br />

or work shop.<br />

Fruit cellar or cold storage room.<br />

Two bath rooms.<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

There are only three persons in our family, our son is<br />

15, and in a couple years there will only be two.<br />

We do not wish to limit you too much in designing<br />

the home but we both like stone and glass (the<br />

laminated stone which is not native of Michigan,<br />

laid in the same manner of that at Fallingwater,<br />

Bear Run, Penn.)<br />

We like dishes and books and want ample space<br />

for these.<br />

Woodward is a busy thoroughfare and we believe<br />

the house should be far back on the lot.<br />

We hope that the lot can be left in a natural condition<br />

as much as possible.<br />

We like the idea of a “car port” rather than a garage.<br />

Possibly, we may some day add a swiming [sic]<br />

pool, as the land lends itself to this.<br />

The road around the property is private, and there is<br />

an easement of 20 feet from all lot lines.<br />

We would like to have the cost held to approximately<br />

8,000 dollars.<br />

We also like your ideas regarding the relation of<br />

house and garden, but the porch or terrace would<br />

need to be screaned [sic] because the section is<br />

quite wild.<br />

We can discuss details when we see you. 22<br />

Later, in a 1946 article on the Affleck house in the<br />

journal Progressive Architecture, the Afflecks summarized<br />

and augmented this original list, claiming

they told Wright, “We don’t like attics; we don’t like<br />

basements, and we don’t like furniture,” and asked<br />

him for “a house with a lot of windows, a large fireplace,<br />

a carport instead of a garage, room enough<br />

for three people to live in but large enough for six to<br />

sleep in.” 23<br />

9<br />

Bloomfield Hills in 1940<br />

Bloomfield Hills was a very small and new community<br />

in 1940, but it was already gaining a reputation<br />

around metropolitan Detroit as a desirable residential<br />

location for wealthy automobile executives and<br />

other professionals. Affleck described it as “not a<br />

cheap neighborhood” with many “Old English”<br />

houses costing more than $50,000. 24 While Bloomfield<br />

Township had been incorporated in 1827, the<br />

town of Bloomfield Hills had only recently been incorporated<br />

in 1932. The 1940 U.S. census listed its<br />

sparse population at 1,281. 25 There really was no<br />

town center or shopping district; nearby Birmingham,<br />

with over 11,000 inhabitants, fulfilled those<br />

needs. The cultural center of Bloomfield Hills was<br />

the Cranbrook campus, a wooded 315-acre oasis<br />

consisting of three schools and nearly thirty buildings,<br />

courtyards, and pools designed by Finnish architect<br />

Eliel Saarinen. 26 Curiosity later would bring many artist<br />

and architect visitors from Cranbrook, many of<br />

whom became friendly with the Afflecks, including<br />

Saarinen and sculptor Carl Milles. 27<br />

Wright’s Design<br />

Wright’s typical working method by the 1930s involved<br />

designing from a distance. He rarely visited<br />

the site for one of his houses more than once, and in<br />

many cases he never visited at all, working instead<br />

from photographs and topographic maps supplied<br />

by the client. This was the process he used with the<br />

Afflecks. Wright did not see the property before creating<br />

the house. He began making drawings in July<br />

1940. From the beginning he conceived the project<br />

as a Usonian house, albeit a slightly more elaborate<br />

version. The drawings envisioned a structure of almost<br />

2,400 square feet in an L-shape, with the longer<br />

leg anchored into the hillside and the shorter leg a<br />

boldly cantilevered living room/dining room/terrace<br />

hanging over the ravine. As Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer has<br />

pointed out, Wright situated the house “diagonally<br />

to the contour lines to take full advantage of the<br />

sloping terrain in its woodland setting.” 28 The picturesque<br />

siting and dramatic cantilever responded<br />

to Gregor’s desire to have Wright devise something<br />

special, indicated by a letter sent just before the first<br />

drawings were produced. “Bloomfield is considered<br />

an ART centre and now we have an opportunity to<br />

show what art in architecture really is and fortunately<br />

there will be no chance to compare it with any<br />

other house,” boasted Gregor. 29<br />

Taliesin Drawing<br />

Taliesin Drawing

Pursuant to his usual method, Wright planned the<br />

house on a grid. The four-foot-square modules used<br />

to arrange the spaces and visible in plan drawings<br />

are inscribed in the concrete floor. What cannot immediately<br />

be seen is that the module also organized<br />

the house vertically. Wright used grids to impart order<br />

on a house in plan and elevation and to assure that<br />

the parts bore a relationship to each other – in this<br />

case, a proportional relationship governed by the<br />

module.<br />

10<br />

Photograph by Balthazar Korab<br />

The Pew House, Wisconsin. Photograph from http://farm4.<br />

static.fl ickr.com/3589/3602796344_44656dc9c9.jpg<br />

The Affleck house was to be a special type of Usonian<br />

with two stories and a terrace; in fact, it belonged<br />

to a family of houses that Wright originated in 1932<br />

with the first (and unbuilt) scheme for the Malcolm<br />

Willey house in Minneapolis. In that important design<br />

Wright created a floor plan with a second-floor living<br />

room intended to take advantage of views of<br />

the surrounding landscape. Wright imagined a balcony<br />

extending from the living room, bounded by a<br />

parapet wall made of overlapping wooden boards.<br />

While not a Usonian house in the true sense, the first<br />

Willey house project introduced many of the core<br />

concepts adapted to later houses.<br />

In 1938, the year before the Afflecks’ request, Wright<br />

embarked on a series of designs for Usonians with<br />

balconies attached to elevated living rooms. One<br />

was a house for John and Ruth Pew near Madison,<br />

Wisconsin. The Pews owned a hillside lot on the shore<br />

of Lake Mendota very similar to the one purchased<br />

by the Afflecks in Bloomfield Hills. Wright decided to<br />

take advantage of the landscape and the view and<br />

resurrected the balcony from the first Willey scheme,<br />

complete with lapped board parapet walls. The<br />

Pew house showed Wright’s propensity for using the<br />

ground to serve as the catalyst for a building’s design.<br />

Wright described his approach in a book published<br />

just two years before meeting the Afflecks:<br />

With the purpose or motive of the building we are to<br />

build well in mind, as of course it must be, and proceeding<br />

from generals to particulars, as “from-withinoutward”<br />

must do, what consideration comes first?<br />

The ground, doesn’t it? The nature of the site, of the<br />

soil and of the climate comes first. Next, what materials<br />

are available in the circumstances…?<br />

We start with the ground…<br />

Why should the building try to belong to the ground<br />

instead of being content with some box-like fixture<br />

perched upon the rock or stuck into the soil, where it<br />

stands out as mere artifice…?<br />

The answer is found in the deal stated in the abstract<br />

dictum, “Form and function are one.” We must begin<br />

upon our structure with that.

The ground already has form. Why not begin to give<br />

at once by accepting that? Why not give by accepting<br />

the gifts of nature?...<br />

Is the ground a parcel of prairie, square and flat?<br />

11<br />

Is the ground sunny or the shaded slope of some hill,<br />

high or low, bare or wooded, triangular or square?<br />

Has the site features, trees, rocks, stream, or a visible<br />

trend of some kind? Has it some fault or a special virtue,<br />

or several?<br />

In any and every case the character of the site is the<br />

beginning of the building that aspires to architecture.<br />

And this is true whatever the site or the building<br />

may be. 30<br />

Gregor Affleck was aware of the Pew house, probably<br />

as a result of Wright’s showing him the project<br />

during a visit to Taliesin. In fact Wright may have<br />

proposed a similar design for the Bloomfield Hills site,<br />

judging by a letter Gregor sent to Wright in June 1940<br />

which indicated that “the house you are building<br />

on Mendota Drive at Madison would be quite suitable<br />

for our lot.” 31 Wright continued to explore the<br />

second-floor balcony in houses for George Sturges<br />

(1939, Brentwood Heights, California) and Lloyd Lewis<br />

(1939, Libertyville, Illinois).<br />

Design Changes<br />

The existing correspondence in the Frank Lloyd<br />

Wright Archives tells the story of a very smooth design<br />

process for the Affleck house. There are no recorded<br />

disagreements between client and architect. Only a<br />

few design aspects were even altered from the original<br />

conception. For example, what appears to be<br />

the earliest floor plan does not include closets in the<br />

two smaller bedrooms. Affleck wrote to Wright specifically<br />

requesting wardrobes in these rooms, as well<br />

as suggesting they be widened (and, consequently,<br />

the entire bedroom wing of the house) by two feet.<br />

Affleck also rejected the first version of the basement<br />

utility room, claiming it was too small for his intended<br />

use.<br />

In the initial drawings, Wright imagined an axis that<br />

led from the main entry through the loggia space<br />

and straight out another door to a “garden,” with<br />

the stairs down to the garden aligned with the axis.<br />

In later versions, and as built, the stairs were shifted<br />

perpendicular to this axis to run parallel with the bulk<br />

of the house, and the single door out to the garden<br />

became a wall of French doors like those separating<br />

the living room from the outdoor terrace. Wright also<br />

modified the loggia from the original conception.<br />

The first drawings show a more formal space, with a<br />

large, square opening in its center and a short spur<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze

wall separating it from the single entry to the garden.<br />

The opening housed a “light well” (called a<br />

“lantern” by Affleck) centered over a small pool<br />

at ground level, with operable windows that could<br />

open to allow cool air to circulate vertically from<br />

below the house; this was a smaller-scale version<br />

of an element he first used at Fallingwater. Perhaps<br />

realizing that the square light well impeded<br />

circulation through the loggia, or influenced by Affleck’s<br />

suggestion to move or eliminate it, Wright<br />

changed it to a rectangular shape and pushed<br />

it off to the side, while also removing the spur wall<br />

screening the garden entry. These gestures made<br />

the space asymmetrical but opened it to better<br />

circulation patterns.<br />

12<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Another alteration to the original plans during the<br />

design phase dealt with the relationship between<br />

the house’s public and private areas. The first plan<br />

seems to show no elevation difference between<br />

public wing and bedroom wing, while later drawings<br />

– and the house as built – depict the private<br />

bedroom wing a half-story higher than the loggia.<br />

All of the early floor plans and most other drawings<br />

also showed the loggia as a separate room,<br />

capable of being closed off from the rest of the<br />

house. No doors, however, were ever installed,<br />

and instead the loggia serves as an intermediate<br />

space for passing through rather than a room<br />

onto itself. 32<br />

Possibly the most important modification to the<br />

original concept – and certainly the one with the<br />

biggest financial impact – concerned the nature<br />

of the materials. As cited above, as part of their<br />

“requirements” list the couple asked for “the laminated<br />

stone which is not native of Michigan, laid<br />

in the same manner of that at Fallingwater.” 33 In<br />

early August 1940, after Wright had sent the Afflecks<br />

his first drawings, they still favored stone<br />

walls but a conflict seems to have arisen between<br />

Gregor and Elizabeth. “Mrs. Affleck still thinks that<br />

she likes stone,” Gregor wrote to Wright. “Personally,<br />

I like brick and also the money that could<br />

be saved by using it.” 34 Wright’s response was<br />

equivocal. The series of elevation and perspective<br />

drawings made by Wright and his apprentices<br />

in the summer of 1940 include some that clearly<br />

anticipate stone walls and others where the material<br />

could be either stone or brick. In September<br />

Gregor continued to mention stone but at some<br />

point afterward the decision was made to switch<br />

to brick. Although the house was eventually constructed<br />

with brick walls, two aspects of the proposed<br />

stone design survived. The first was a rough<br />

stone retaining wall along the hillside that bowed<br />

out from the northeast corner of the carport to the<br />

entry drive. The second was more subtle. Gregor<br />

had added a handwritten message to a letter

13<br />

to Wright in September 1940, suggesting a mark on<br />

one of the stones in the form of an abstracted “G”<br />

and “A” superimposed – much like Wright’s official<br />

signature mark, as Affleck pointed out. 35 The final<br />

choice of brick over stone rendered this suggestion<br />

moot, but in the house there are small windows in the<br />

bathrooms and in the clerestory at the north end of<br />

the living room containing a design that some see as<br />

the abstracted initials but in a different form. Gregor<br />

began using stationery with this pattern as early as<br />

November 1941. It may be that Wright liked Gregor’s<br />

idea of a personal mark and found a way to incorporate<br />

it despite the decision not to use stone walls<br />

in the house.<br />

The walls were not the only surfaces to undergo revisions<br />

during the design phase. It appears that the<br />

living room floor was originally to be wooden, as revealed<br />

by a letter from Harold Turner to Wright in early<br />

1941 which claims, “You suggested to the Afflecks<br />

last fall to change the wood flooring in the front part<br />

of the building to concrete slab flooring.” 36 This implies<br />

that early in the design process the house was<br />

going to vary from the typical Usonian by eliminating<br />

the concrete slab – with its radiant heating system<br />

– in the living room. Whether the Afflecks or Wright<br />

proposed the wooden floor is unknown. Gregor responded<br />

to Turner’s suggestion with his usual deference<br />

to Wright, stating that he would prefer a solid<br />

concrete floor but would follow Wright’s desires. 37 In<br />

the end a concrete slab was employed.<br />

Construction<br />

With the drawings for the proposed house completed,<br />

the next step was to fi nd a competent contractor<br />

who could deal with Wright’s unique designs.<br />

Gregor fi rst suggested a longtime acquaintance<br />

named C. Lloyd Rix. 38 He eventually settled on a<br />

builder who had apparently had trouble executing<br />

Wright’s proposal. Gregor was exasperated; he<br />

later claimed, “The plans were ready in the summer<br />

of 1940 but I fumbled around with a builder who<br />

could not read the plans. Mrs. A. could read them<br />

and her only experience was reading the plans for<br />

a dress.” 39 Wright then recommended a trusted<br />

hand. Harold Turner was a Danish-born cabinetmaker<br />

with no building experience who had made<br />

the transition into larger construction when Wright<br />

hired him to oversee the erection of the Hanna<br />

House (1936) in Palo Alto, California. He subsequently<br />

became one of Wright’s favorites, working on fi ve<br />

other Wright-designed houses by that time, including<br />

the Goetsch-Winkler House (1939) in Okemos,<br />

Michigan. Turner’s work was characterized by fi ne<br />

craftsmanship, executed despite the unique and<br />

exacting specifi cations of Wright’s designs. While<br />

working on the Affl eck house, Turner also directed<br />

the construction of Wright’s house for Carlton and<br />

Margaret Wall (1941) in nearby Plymouth, Michigan.<br />

Photograph by Gregor Affl eck

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

After fi nishing the Affl eck and Wall houses Turner<br />

built a residence for himself in Bloomfi eld Hills. He<br />

later became a “designer-builder,” creating and<br />

constructing Wrightian-styled houses for numerous<br />

clients in the suburbs north of Detroit.<br />

By December 1940, Gregor had enlisted Turner’s<br />

help, paying him by the month. Technically<br />

Turner was not the Affl ecks’ contractor, only the<br />

supervisor, overseeing the work of individual contractors<br />

for the heating, plumbing, and roof. The<br />

structure rose rather swiftly when the building<br />

season returned the following spring. Gregor later<br />

reported that groundbreaking for his house took<br />

place on May 1, 1941. By mid-July, Turner reported<br />

to Wright that the house was “rapidly taking<br />

form”: the brick layers would be fi nished within<br />

a week, the fl oors were 60 percent done, and a<br />

roof over the living room was completed. 40 The<br />

family moved in some time in October, and construction<br />

on the house was fi nished by the end<br />

of 1941. By all accounts Gregor was very satisfi ed<br />

except for one aspect – he felt the carport was<br />

too small. The remaining correspondence from<br />

the project shows that he complained about the<br />

carport in December, shortly after the house was<br />

completed, and again the next April. There is no<br />

indication, however, that the carport was ever altered<br />

beyond its original dimensions.<br />

The house immediately proved to be a curiosity<br />

among members of the Detroit region’s art and<br />

architectural communities. Gregor reported that<br />

soon after construction began architects started<br />

visiting on a weekly basis. Later, when the house<br />

was fi nished, the stream of callers grew deeper.<br />

According to Gregor, “Weekends were a nightmare.<br />

Just like rolling a snowball each person<br />

brought a friend who immediately came back<br />

with two more.” 41 And this continued for the entire<br />

time the Affl ecks lived in the house.<br />

The House as Built<br />

The Affleck house as conceived by Wright exhibited<br />

all the trademarks of his domestic architecture<br />

as they had been developed in the first<br />

decade and a half of the twentieth century – in<br />

the so-called “Prairie Style” houses – and would<br />

be further elaborated in the Usonian works. First<br />

and foremost, Wright attempted to harmonize the<br />

house with the land. Since the early 1900s, Wright<br />

had emphasized the nexus between building and<br />

setting as crucial. “A building should appear to<br />

grow easily from its site and be shaped to harmonize<br />

with its surroundings if Nature is manifest the,”<br />

he wrote in 1908. 42 Like his other works on sloping<br />

sites, the Affleck house emerges from the hillside<br />

rather than sitting atop its crown.<br />

14

15<br />

Approach<br />

The Affleck house, like Wright’s other Usonians, turns<br />

its back to the public, offering a mostly windowless<br />

brick wall to arriving visitors. This tendency exhibits<br />

Wright’s view of the home as a safe haven for the<br />

family where privacy is paramount. From the outside,<br />

particularly for those visitors approaching the house<br />

from Woodward Avenue up the driveway, nothing<br />

can be seen of the interior. The living area is elevated<br />

from the ground and hidden behind the terrace’s<br />

parapet wall and a large brick buttress. As the visitor<br />

moves closer to the house, curving toward its north<br />

side, he or she is greeted by a somewhat formidable<br />

structure of largely brick walls; the only visible windows<br />

are small clerestories along the private wing<br />

just below the extended eave. This austere façade<br />

is countered on the other side of the house, away<br />

from the driveway and facing what was once a forest,<br />

where prominent windows indicate the locations<br />

of bedrooms and loggia, and the open glass-filled<br />

terrace overlooks the ravine. Once inside, however,<br />

the house seems extremely open to light and the<br />

outdoors. The living room’s French doors, as well as<br />

those in the loggia, dematerialize the sense of enclosure.<br />

The house’s appearance is distinctly horizontal in<br />

keeping with Wright’s belief that the horizontal line of<br />

the ground plane, reflected in a building, reinforced<br />

the building’s symbolic connection to its location.<br />

Describing the Usonian house idea in the early 1940s,<br />

Wright claimed that the Usonian “extends itself in the<br />

flat parallel to the ground. It will be a companion to<br />

the horizon.” 43 This horizontal emphasis can be seen<br />

in the extended, overhanging flat roofs of the house<br />

and carport, the lapped boards of cypress wood<br />

siding, the cantilevered terrace extending off the living<br />

room, the clerestory windows that run along the<br />

public face of the house, and even in the brickwork<br />

of the masonry sections, where the horizontal joints<br />

between the bricks were raked to a greater-thanaverage<br />

depth while the vertical joints were built<br />

up with mortar until they were flush with the wall’s<br />

surface – per Wright’s command. Natural materials<br />

were of course highlighted: except for the glass windows,<br />

viewers of the house see only brick and wood.<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Materials<br />

Inside and out, most walls consist of twelve-inch cypress<br />

boards laid vertically, with each successive<br />

course lapping the previous one. These sandwich<br />

walls contain a three-quarter-inch plywood core<br />

and no rigid framework. Because the boards are<br />

lapped, none of the vertical wood surfaces are<br />

straight – some taper to the top while others narrow<br />

at the bottom. Whether intentional or not, this means<br />

the profiles of the wooden walls – including doors –<br />

echo the sloping hillside that supports the house. All

of the corners are mitered, which is a difficult task<br />

in itself but extremely arduous when combined<br />

with inclined walls. They are a testament to Harold<br />

Turner’s precise craftsmanship.<br />

Entry<br />

The house’s entry is unobtrusive, tucked beneath a<br />

low-hanging carport roof barely six-and-a-half feet<br />

high, and flanked by a plain brick wall and vertical<br />

slit window. Wright partially relieved the sense<br />

of compression by punching a skylight through the<br />

roof just in front of the doorway, but the overall effect<br />

is still cramped. Upon entering the house one<br />

first passes through a small foyer, which extends<br />

the constricted height of the carport, before stepping<br />

into the loggia where the space dramatically<br />

opens up to two stories.<br />

16<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Loggia<br />

The interior arrangement similarly reveals typical<br />

Wrightian gestures. The house consists of three major<br />

areas: public – where guests might be allowed; intermediate<br />

(the loggia) – to serve as a transition between<br />

outside and indoors as well as between the<br />

two other areas of the house; and private, consisting<br />

of three bedrooms and two bathrooms. These<br />

three zones are distinguished by their size, shape,<br />

and relationship to each other.<br />

The loggia is a light-filled wonder. Its skylit ceiling allows<br />

views of the sky and clouds above, just as a wall<br />

of French doors on the south side offers a prospect<br />

of the hillside and wooded surroundings and a bank<br />

of windows in the west wall exposes a view into the<br />

upper part of the first bedroom. A third feature, the<br />

“light well,” dominates the room at floor level. It consists<br />

of windows set flush with the floor, surrounded<br />

by a short wall of lapped boards that mimics the<br />

wooden walls found throughout the house. When<br />

opened, the windows offer a view to a small reflecting<br />

pool below, and allow cool air to circulate up<br />

and through the main rooms. Elizabeth called the<br />

light well “an organic air conditioning unit.” 44 The<br />

light well is integrated into the wall and turns the corner<br />

from the loggia into the living room, visually connecting<br />

the two rooms. The short walls around the<br />

opening also screen the circulation path from the<br />

closets and restroom along the loggia’s north side.<br />

Photograph by Balthazar Korab<br />

The loggia also demonstrates Wright’s effort to unify<br />

interiors and exteriors. It is the most transparent room<br />

in the house, with a wall and ceiling that present<br />

only a minimal barrier. Wright employed a trellis<br />

outside the loggia to enhance this connection. The<br />

trellis over the rear entry to the loggia is an extension<br />

of the skylights inside, using the same pattern<br />

of framed openings, which serves to extend space<br />

beyond the walls of the house and blur the distinction<br />

between inside and outside.

17<br />

Living Room and Terrace<br />

The living room and terrace comprise the public area<br />

and act as the heart of the Affleck house. This combination<br />

of spaces embraces many of Wright’s salient<br />

concepts of domestic architecture, including such<br />

notions as the sanctity of family (symbolized by the<br />

oversized hearth), the fireplace as the spatial locus of<br />

family life, the psychological attraction of prospect/<br />

refuge design, and the essential connection between<br />

nature and architecture. All other spaces in<br />

the Affleck house are secondary.<br />

The living room is a rectangle forty feet long and sixteen<br />

feet wide. It is dominated by two elements: a<br />

continuous row of French doors that extends along<br />

most of the eastern side and part of the southern wall;<br />

and a massive fireplace set off-center in the western<br />

wall. Because of its size, “some people think our fireplace<br />

will never work,” wrote Gregor Affleck. 45 But<br />

they were wrong. Its function, however, was almost<br />

secondary to its symbolic value. For decades Wright<br />

had been utilizing immense living room hearths to signify<br />

family togetherness and harmony – a characteristic<br />

design feature he may have adopted from the<br />

nineteenth century Arts & Crafts movement.<br />

The living room demonstrates another of Wright’s design<br />

characteristics – the use of a diagonal axis. As<br />

historian Neil Levine has demonstrated, Wright utilized<br />

diagonal planning throughout his career as a means<br />

of allowing for a “new sense of freedom, breadth,<br />

and connection to nature” while serving as “the positive<br />

organizing principle of his planning.” 46 Early in his<br />

career Wright began to place doorways or entries in<br />

the corner of a room to give the impression of greater<br />

interior depth. At his own home, Taliesin, in Spring<br />

Green, Wisconsin, Wright introduced the diagonal<br />

axis that extends from one corner of a rectangular<br />

room through the opposite corner in the far wall<br />

and out into the landscape. This manner of imparting<br />

depth to a space – and harmonizing inside and<br />

outside – was emphasized by either partially or fully<br />

glazing the corner where the diagonal axis breaches<br />

the enclosure and continues outdoors. In most of<br />

Wright’s Usonian houses, then, one can stand in front<br />

of the fireplace and look out across the living room<br />

through a transparent corner to see nature. At the<br />

Affleck house this view travels through the corner,<br />

over the terrace, and out to the ravine in front of the<br />

house slightly below treetop level. The vista unites the<br />

structure with its surroundings, giving the impression<br />

that the living room continues outside and into the<br />

trees and sky with only a minimal barrier between.<br />

Wright described this spatial effect in his autobiography,<br />

claiming that the Usonian house “liberates the<br />

occupant in a new spaciousness. A new freedom.” 47<br />

This was part of Wright’s career-long effort to remove<br />

barriers both inside the house and between inside<br />

and outside. “There is a freedom of movement, and<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

a privacy too, afforded by the general arrangement<br />

here that is unknown to the current ‘boxment,’<br />

Wright boasted of the Usonian houses.<br />

“Withal, this Usonian dwelling seems a thing loving<br />

the ground with a new sense of space, light, and<br />

freedom – to which our U.S.A. is entitled.” 48<br />

This vista from the living room, accentuated from<br />

the outdoor terrace, takes advantage of the site’s<br />

unique characteristics and enables the occupants<br />

to view natural surroundings from deep within the<br />

house. And in so doing it may tap into something<br />

rooted in our subconscious minds. One of the most<br />

interesting of Wright’s design techniques is his use<br />

of what has been termed “prospect and refuge.”<br />

Popularized by British geographer Jay Appleton<br />

in the 1970s, prospect and refuge theory relates<br />

to what appears to be an innate human attraction<br />

to places that are secure and hidden (refuge)<br />

while also offering a protected and elevated view<br />

of the surroundings (prospect). The theory postulates<br />

that this attraction evolved on the African savannah<br />

during Homo sapiens’ earliest days, helping<br />

our ancestors survive in a hostile environment. 49<br />

Wright began to experiment with prospect and<br />

refuge in his “Prairie Style” houses and continued<br />

in the Usonians. The Affleck house demonstrates<br />

the concept well. Inside the low-ceilinged living<br />

room, looking out through the transparent wall at<br />

the trees beyond, one gains a sense of safety and<br />

solitude.<br />

Another design element Wright incorporated<br />

into the Affleck house is the principle of compression<br />

and release. Actually an ancient technique,<br />

seen as far back as megalithic tombs of prehistoric<br />

times, compression and release deals with<br />

the viewer’s psychological experience of space.<br />

It involves leading the visitor in sequence from a<br />

small, constricted space to a larger, open one.<br />

The psychological effect of this series of experiences<br />

makes the second, larger space appear even<br />

more spacious. Wright may have learned the<br />

technique from Louis Sullivan, his acknowledged<br />

mentor from the early days of Wright’s career. In<br />

the Affleck house this can be seen at work when<br />

entering through the main door. After walking under<br />

the extremely low carport roof, which imparts<br />

a feeling of compression, and through the entry,<br />

the visitor encounters the loggia, which explodes<br />

to two stories and is full of light. A similar sensation<br />

is conveyed when walking through the living room<br />

– which is dark and enclosed with a rather low ceiling<br />

– and out onto the terrace and thus to a place<br />

without walls or ceilings.<br />

The living room’s northern end was for dining.<br />

Wright attached a row of shelves to the wall for the<br />

Afflecks’ to display their dinnerware, and made a<br />

18

dining corner by locating the dinner table next to<br />

the kitchen. At the opposite end, Wright created a<br />

phonograph cabinet which protruded into the room<br />

perpendicular from the wall. The cabinet formed a<br />

special nook in the living room’s southern end for the<br />

Afflecks’ piano.<br />

19<br />

The terrace extends the living room space out of<br />

doors. It is large – fifty-six feet long, six feet wide next<br />

to the living room and sixteen feet wide at the cantilevered<br />

southern end. Here the Afflecks could enjoy<br />

an unobstructed view of their scenic location. The<br />

terrace extends the full length of the living room and<br />

turns the corner to veer off the house in a dramatic<br />

cantilever which provides the house’s aesthetic highlight.<br />

Wright used cantilevers as a means to energize<br />

his structures, creating terraces, balconies, and roofs<br />

that hover in mid-air with no visible means of support.<br />

Kitchen<br />

Wright began calling kitchens “workspaces” in the<br />

Usonian houses in recognition of the changed social<br />

circumstances that required middle-class women,<br />

more and more, to do their own cooking without<br />

the aid of full- or part-time servants. His designs were<br />

governed by efficiency. The Affleck workspace is<br />

a twelve-foot-by-ten-foot brick-walled room tightly<br />

packed with appliances, counters, and storage<br />

compartments, and a stairway leading down to the<br />

lower level. Wright’s Usonian kitchens were strictly utilitarian<br />

rooms without embellishment and often not<br />

enjoying the same connection to the outside as other<br />

rooms. Their purpose, as at the Affleck house, was<br />

to furnish the necessities for working in a streamlined<br />

space that was directly adjacent to the dining area.<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Bedroom Wing<br />

The third and final zone of the house, containing the<br />

family’s private rooms, is raised a half-level above the<br />

plane of the loggia and largely out of sight. This is a<br />

move Wright made in many of the Usonians to signal<br />

the hierarchy between the public and private zones.<br />

Rectangular in form, and the largest of the house’s<br />

three areas, the private wing features a narrow corridor<br />

or “gallery” along one side, four feet wide and<br />

illuminated by a continuous row of clerestory windows.<br />

As in most Usonians, there are no spaces in the<br />

house devoted strictly to circulation, so even this hallway<br />

is lined with shelves on one side and closets and<br />

drawers on the other.<br />

Three bedrooms and two bathrooms are arranged<br />

in line on one side of the gallery. The bedrooms are<br />

compact, in keeping with Wright’s desire for simplification.<br />

The master bedroom is sixteen-by-twelve feet,<br />

while the secondary bedrooms measure twelve feet<br />

square. All three rooms are entered through a corner<br />

in an attempt to make their relatively small spaces<br />

seem a little larger, and in harmony with Wright’s af-<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze

finity for diagonal axes. The first bedroom encountered<br />

in the private wing contains a set of windows<br />

that allows a view over the loggia and into the living<br />

room. Between it and the second bedroom is<br />

a skylit bathroom. At the very end of the house is<br />

the master bedroom, which contains its own skylit<br />

bathroom and a specially designed vanity.<br />

Lower Level<br />

The Affleck house is unique in the Usonian world as<br />

one of the few examples with a lower level. Taking<br />

advantage of the hillside location, Wright placed<br />

the utility room, along with a “maid’s room” and<br />

bathroom, beneath the kitchen and living room.<br />

Ironically, the servant’s quarters were never used<br />

as such since the Afflecks’ never employed a<br />

maid. Wright also created a separate “shop” or<br />

workroom for Gregor beneath the loggia – a place<br />

for Affleck to develop photographs and store tools.<br />

20<br />

Photograph by Harvey Croze<br />

Wright turned the opening under the cantilevered<br />

terrace into a rest area, attaching bench seats to<br />

the structural piers and paving a small brick terrace<br />

around the reflecting pool. This space could<br />

be used to escape the heat on summer days, or<br />

perhaps even as another place to contemplate<br />

the site’s natural beauty. In many of the designs<br />

for the house Wright envisioned a small stream running<br />

down the hill, under the terrace, and into the<br />

pond at the ravine’s bottom, so he incorporated a<br />

Japanese-style footbridge and small boulders beneath<br />

the overhang to enhance the stream’s attractiveness.<br />

No existing photographs depict such<br />

a stream, however, and the site today gives no indication<br />

of running water.<br />

An interesting aspect of the Affleck House is the<br />

cramped passageway on the lower level between<br />

the utility room/maid’s room suite and Gregor’s<br />

workroom. Present-day visitors are amazed by its<br />

awkward four-foot height. The origins of this basement<br />

tunnel are shrouded in mystery. It seems<br />

clear that the passage was not part of the original<br />

design since none of the surviving drawings by<br />

Wright and his apprentices show any connection<br />

between these two areas. Thus there is no verified<br />

explanation for its presence. Rumors blame an<br />

unskilled contractor who could not read Wright’s<br />

plans, but that story is suspect given that Harold<br />

Turner, a skilled builder by the time work began on<br />

the house, supervised construction. A more likely<br />

explanation is that some sort of accident occurred<br />

that could not be corrected before the concrete<br />

dried.<br />

Furnishings<br />

In typical fashion, Frank Lloyd Wright designed

21<br />

furniture for the Afflecks to match their house. 50 The<br />

pieces were simple and horizontally oriented, fitting<br />

with the house’s design theme. For the living room,<br />

Wright designed a dining table, end tables, and a set<br />

of wooden chairs with upholstered backs and seats;<br />

each chair could be used individually or combined<br />

with others to form a sofa. Other chairs for the house<br />

consisted of a Y-shaped plywood base supporting<br />

an L-shaped seat and back. All of the chairs and<br />

tables were unadorned, emphasizing the nature of<br />

their materials (cypress plywood) to match the rest<br />

of the house.<br />

There is evidence that the Afflecks were not entirely<br />

pleased with their Wright-designed furniture. Ruth<br />

Adler Schnee, a pioneer of mid-century modernist<br />

furniture and interior designs in Michigan who worked<br />

with Minoru Yamasaki and Buckminster Fuller, among<br />

others, recalled being hired by the Afflecks to provide<br />

alternatives. According to Schnee, “the Afflecks<br />

asked me to help them because Frank Lloyd Wright<br />

had designed furniture for them, built into the house.<br />

It was so uncomfortable that they wanted me to<br />

see if I could improve on that.” 51 Historical evidence<br />

confirms that the family owned many pieces of non-<br />

Wright furniture.<br />

In late summer/early fall 1942, Wright designed special<br />

wool rugs for the living room and loggia and Gregor<br />

hired a weaver to fabricate them. They featured a<br />

series of multi-colored diagonals against a backdrop<br />

of vertical lines. But as envisioned, the rugs’ thickness<br />

was problematic since the French doors leading out<br />

to the terrace reached down to within millimeters of<br />

the floor. In an exchange of correspondence in late<br />

1942, Wright suggested trimming the bottom of the<br />

doors to gain the necessary clearance. Photographs<br />

from that time show a more practical solution – the<br />

rugs are moved away from the doors.<br />

At approximately the same time Affleck requested a<br />

“plywood mural” for the loggia. 52 It may be that the<br />

proposal was aimed at Wright’s personal secretary,<br />

Eugene Masselink, a talented artist who designed a<br />

number of plywood screens and murals for Wright<br />

houses in the 1950s. Masselink’s work typically included<br />

dramatic vertical slashes, circles, and triangles in<br />

bright colors; some of these abstract art pieces had<br />

the secondary effect of emphasizing the diagonal<br />

axes that placed such an important role in Wright’s<br />

planning at the Affleck house and elsewhere. The<br />

nature of that item is unclear, and the house shows<br />

no signs of a mural of any type being installed. 53<br />

After construction finished and the family moved<br />

in, Gregor Affleck tabulated the construction costs,<br />

and estimated the total expenditure at approximately<br />

$19,000. This was extremely expensive for the<br />

time, since the average American house cost about<br />

Eugene Masselink Mural, at Grand Rapids Art Museum<br />

http://www.artmuseumgr.org/uploads/assets/masselinkweb.png

$4,000. It also represented a noteworthy departure<br />

from the planning stages, when the Afflecks<br />

informed Wright they “would like to have the cost<br />

held to approximately 8,000 dollars.” 54 Such a significant<br />

overrun was fairly typical of Wright, however,<br />

and in part exposes the uncertainties of dealing<br />

with the Usonians’ special construction requirements.<br />

While the first Usonian house, built in 1936 for<br />

Herbert and Katherine Jacobs in Madison, Wisconsin,<br />

had cost $5,500, most were more expensive<br />

than this. The cost also indicates the Afflecks’ status;<br />

the house should be regarded as a “high end”<br />

Usonian, specially crafted for a wealthy family, and<br />

not a standard model intended for the masses.<br />

22<br />

Photograph by Jessica Aguilar<br />

Photograph by Megan Connor<br />

Subsequent Life and Influence<br />

Wright apparently thought very highly of the Affleck<br />

House. He included a model and two drawings<br />

of the house, which was then under construction,<br />

in a major retrospective of his work entitled,<br />

“Frank Lloyd Wright: American Architect,” at the<br />

Museum of Modern Art in New York. 55 This was significant<br />

because Wright chose the projects himself<br />

and designed the exhibit, including the Affleck<br />

House alongside such famous works as the Robie<br />

house, the Johnson Wax Company, Fallingwater,<br />

and Taliesin. Only sixteen other models were presented.<br />

In a proposed catalog, Wright described<br />

the Affleck house as having a “living room and<br />

terrace thrust boldly over a pool.” 56 The exhibition<br />

ran from November 1940 to January 1941, and<br />

introduced the house within the larger context of<br />

Wright’s oeuvre.<br />

A few years later, the Affleck House played a prominent<br />

role in General Motors’ advertising campaign<br />

for the 1948 Oldsmobile Futurama, one of the car<br />

manufacturer’s first new post war models. The<br />