Economic Valuation of Mabamba Bay Wetland System of ...

Economic Valuation of Mabamba Bay Wetland System of ...

Economic Valuation of Mabamba Bay Wetland System of ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

M.Sc. Programme ‘’Management <strong>of</strong> Protected Areas’’<br />

<strong>Economic</strong> <strong>Valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> <strong>Wetland</strong> <strong>System</strong> <strong>of</strong> International<br />

Importance, Wakiso District, Uganda<br />

Author : Simon Akwetaireho<br />

Supervisor : Pr<strong>of</strong>. Michael Getzner,<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Economic</strong>s,<br />

Alps-Adriatic University <strong>of</strong> Klagenfurt,<br />

Universitätsstrasse 65-67,<br />

A – 9020 Klagenfurt<br />

Tel: +43 (0) 463/27004192, +436764129222<br />

E-mail: Michael.Getzner@uni-klu.ac.at<br />

Carried out at :<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Economic</strong>s,<br />

Alps-Adriatic University <strong>of</strong> Klagenfurt,<br />

Universitätsstrasse 65-67, A – 9020 Klagenfurt<br />

Tel: +436505619219, +256782374594<br />

E-mail: akwetsimo@yahoo.co.uk<br />

Klagenfurt, June 2009<br />

Citation: AKWETAIREHO, S. (2009). ECONOMIC VALUATION OF MABAMBA<br />

BAY WETLAND SYSTEM OF INTERNATIONAL IMPORTANCE, WAKISO<br />

DISTRICT, UGANDA. ALPS-ADRIATIC UNIVERSITY OF KLAGENFURT,<br />

KLAGENFURT, AUSTRIA

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

Declaration <strong>of</strong> honor............................................................................................................ v<br />

Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................vi<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................vii<br />

Executive summary..........................................................................................................viii<br />

Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................... 1<br />

1.1 Justification for performing an economic valuation study........................................ 2<br />

1.2 Rationale for evaluating benefits <strong>of</strong> wetland ecosystem conservation...................... 3<br />

1.3 The objectives <strong>of</strong> the study ........................................................................................ 4<br />

Chapter 2: Literature review ........................................................................................... 5<br />

2.1 <strong>Wetland</strong> conservation benefits .................................................................................. 5<br />

2.2 <strong>Economic</strong> costs associated with wetland conservation............................................. 9<br />

2.3 Reasons why wetlands are still under-valued and over-used ................................. 10<br />

2.4 Solutions to correct externalities; and incentives to support the............................ 11<br />

Chapter 3: Description <strong>of</strong> the study site........................................................................ 13<br />

Chapter 4: Methodology................................................................................................ 20<br />

4.1 Household questionnaire survey ............................................................................. 20<br />

4.2 Contingent <strong>Valuation</strong> Method (CVM)..................................................................... 21<br />

4.3 Benefit Transfer Method.......................................................................................... 25<br />

4.4 <strong>Valuation</strong> using market prices ................................................................................ 25<br />

4.5 Focus group discussions ......................................................................................... 25<br />

4.6 Researcher’s observations ...................................................................................... 26<br />

4.7 Secondary data collection ....................................................................................... 26<br />

Chapter 5: Data analysis and results............................................................................ 27<br />

5.1 Data analysis........................................................................................................... 27<br />

5.2 Household characteristics....................................................................................... 27<br />

5.3 Accessibility to water sources ................................................................................. 28<br />

5.4 Livestock ownership among households ................................................................. 28<br />

5.5 Cultivation <strong>of</strong> cocoyams and sugarcanes................................................................ 29<br />

5.6 Fuel wood collection ............................................................................................... 29<br />

i

5.7 Human-wildlife conflicts ......................................................................................... 30<br />

5.8 Land resources ........................................................................................................ 31<br />

5.9 Contingent <strong>Valuation</strong> results................................................................................... 31<br />

Chapter 6: Discussion ..................................................................................................... 34<br />

6.1 <strong>Economic</strong> values <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland system................................................ 34<br />

6.1.1 Domestic water supply..................................................................................... 34<br />

6.1.2 Support cultivation <strong>of</strong> cocoyams and sugar canes ........................................... 35<br />

6.1.3 Fish catch.......................................................................................................... 36<br />

6.1.4 Recreational and tourism values ...................................................................... 37<br />

6.1.5 Sand harvesting ................................................................................................ 38<br />

6.1.6 Water-based transport ...................................................................................... 39<br />

6.1.7 Harvesting <strong>of</strong> papyrus plants............................................................................ 39<br />

6.1.8 Carbon storage and sequestration..................................................................... 40<br />

6.1.9 Indirect use, optional and Non-use values ....................................................... 40<br />

6.2 <strong>Economic</strong> costs associated with <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland........................................ 43<br />

6.2.1 Opportunity costs ............................................................................................. 43<br />

6.2.2 Costs arising from damages by wild animals................................................... 43<br />

6.2.3 Direct management costs ................................................................................. 43<br />

Chapter 7: Conclusions and recommendations............................................................ 44<br />

7.1 Conclusions ............................................................................................................. 44<br />

7.2 Recommendations.................................................................................................... 45<br />

References ......................................................................................................................... 47<br />

Appendix ........................................................................................................................... 50<br />

Appendix I: Household and contingent survey questionnaire .......................................... 50<br />

ii

List <strong>of</strong> Tables<br />

Table 2-1: Summary <strong>of</strong> Ecosystem services derived from or provided by wetlands......... 7<br />

Table 2-2: Classification <strong>of</strong> total economic values for wetlands ........................................ 9<br />

Table 3-1: Population per Parish by sex .......................................................................... 18<br />

Table 3-2: Population <strong>of</strong> livestock in parishes surrounding <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland....... 18<br />

Table 4-1: Distribution <strong>of</strong> respondents by village............................................................ 21<br />

Table 5-1: Household structure <strong>of</strong> people living adjacent to <strong>Mabamba</strong> wetland............. 27<br />

Table 5-2: Mean and total amount <strong>of</strong> water used per day and year ................................. 28<br />

Table 5-3: Mean and total number <strong>of</strong> livestock in villages around <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland<br />

system.............................................................................................................. 29<br />

Table 5-4: Number <strong>of</strong> cocoyam and sugarcane stems cultivated per annum in Bussi<br />

Parish................................................................................................................ 29<br />

Table 5-5: Bundles <strong>of</strong> firewood consumed by per household per week ........................... 30<br />

Table 5-6: Summary <strong>of</strong> descriptive statistics for household WTA and WTP (US$) per<br />

month................................................................................................................ 31<br />

Table 5-7: Summary <strong>of</strong> protect bids in response to WTA and WTP surveys................... 33<br />

Table 6-1: Stage 1 water borehole costs for human population........................................ 34<br />

Table 6-2: Stage 2 water borehole costs for livestock ..................................................... 34<br />

Table 6-3: Estimated annual total fish catches in year 2008 as presented by landing sites<br />

and fish species................................................................................................. 37<br />

Table 6-4: Water channels, No. <strong>of</strong> boats and total revenues generated ........................... 39<br />

Table 6-5: Estimated annual Total <strong>Economic</strong> Values <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland <strong>of</strong><br />

international importance.................................................................................. 41<br />

iii

List <strong>of</strong> Figures<br />

Figure 3-1: Map <strong>of</strong> Uganda showing location <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> <strong>Wetland</strong> <strong>System</strong> .......... 14<br />

Figure 3-2: Map showing administrative units (Parishes and Villages) around <strong>Mabamba</strong><br />

<strong>Bay</strong> Ramsar Site.............................................................................................. 15<br />

Figure 4-1: Payment card for eliciting WTA for loss <strong>of</strong> access to wetland ecosystem<br />

services............................................................................................................ 23<br />

Figure 4-2: Payment card for eliciting WTP to secure a better access to wetland products<br />

and services ..................................................................................................... 24<br />

Figure 5-1: No. <strong>of</strong> complaints raised against problem animals………………………….30<br />

Figure 5-2: Trends in HH WTA (US$) per month............................................................ 31<br />

Figure 5-3: Trends in HH WTP (US$) per month ............................................................ 32<br />

Figure 6-1: Proportion <strong>of</strong> each ecosystem service (%age <strong>of</strong> TEV)................................... 42<br />

iv

Declaration <strong>of</strong> honor<br />

I herewith declare that I am the sole author <strong>of</strong> the current master thesis according to art. 51 par. 2<br />

no. 8 and art. 51 par. 2 no. 13 Universitätsgesetz 2002 (Austrian University Law) and that I have<br />

conducted all works connected with the master thesis on my own. Furthermore, I declare that I<br />

only used those resources that are referenced in the work. All formulations and concepts taken<br />

from printed, verbal or online sources – be they word-for-word quotations or corresponding in<br />

their meaning – are quoted according to the rules <strong>of</strong> good scientific conduct and are indicated by<br />

footnotes, in the text or other forms <strong>of</strong> detailed references.<br />

Support during the work including significant supervision is indicated accordingly. The master<br />

thesis has not been presented to any other examination authority. The work has been submitted in<br />

printed and electronic form. I herewith confirm that the electronic form is completely congruent<br />

with the printed version.<br />

I am aware <strong>of</strong> legal consequences <strong>of</strong> a false declaration <strong>of</strong> honor.<br />

Klagenfurt, 15 June 2009<br />

Signature:<br />

v

Acknowledgements<br />

I wish to recognize the various contributions by different people and organizations to the success<br />

<strong>of</strong> this field study. Sincere thanks are expressed to Austrian Development Co-operation as<br />

represented by Austrian Agency for International Co-operation in Education and Research (Oead)<br />

for generously funding my two-year academic degree programme at Klagenfurt University under<br />

the North – South Dialogue Scholarship Programme.<br />

The field study was also financially supported by the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG)<br />

with a Royal Dutch Shell plc International Leadership and Capacity Building Programme<br />

Bursary”. In respect <strong>of</strong> this, the financial contribution from Royal Geographical Society is highly<br />

appreciated.<br />

It is also a pleasure to express my deep gratitude to Pr<strong>of</strong>. Michael Getzner, my Masters father for<br />

inspiring and motivating to venture in to the field <strong>of</strong> environmental and ecological economics;<br />

and for supervising and mentoring me at all levels <strong>of</strong> my field research; and specifically for his<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essional, technical guidance and insightful comments. Acknowledgment <strong>of</strong> my gratitude is<br />

equally given to Mr. Michael Jungmeier, Miss Caroline Starched and the entire staff <strong>of</strong> Institute<br />

<strong>of</strong> Ecology, Klagenfurt who organized a series <strong>of</strong> research sessions and scientific excursions in<br />

some parts <strong>of</strong> Europe during which I was able to share my research concept paper with the rest <strong>of</strong><br />

course participants.<br />

Last but not least special recognition is given to the Chief Administrative Officer (CAO) <strong>of</strong><br />

Wakiso district local government for granting me authority to conduct research in and around<br />

<strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland system. On a related note, I very much appreciate technical contributions<br />

and administrative support from CAO’s staff especially the Senior District Environment Officer,<br />

Senior Assistant Secretary (Mr. Ssenduli John) and his staff at Kasanje Sub-county. The various<br />

contributions <strong>of</strong> different local stakeholders, local leaders and local leaders during the data<br />

collection exercise and during Participatory Rural Appraisals is highly acknowledged.<br />

vi

List <strong>of</strong> Acronyms and Abbreviations<br />

Acronyms<br />

BMU<br />

BV<br />

CITES<br />

CMS<br />

CVM<br />

DUV<br />

ECOTRUST<br />

FACE<br />

HH<br />

IUCN<br />

IUV<br />

KSDP<br />

LC<br />

MA<br />

MBGCA<br />

MWETA<br />

MWLE<br />

NEMA<br />

OP<br />

PES<br />

SPSS<br />

TEV<br />

UV<br />

WTA<br />

WTP<br />

XV<br />

Abbreviations<br />

Beach Management Unit<br />

Bequest Values<br />

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species <strong>of</strong> Wild<br />

Fauna and Flora<br />

Convention on the Conservation <strong>of</strong> Migratory Species <strong>of</strong> Wild<br />

Animals<br />

Contingent <strong>Valuation</strong> Methodology<br />

Direct Use Values<br />

Environmental Conservation Trust <strong>of</strong> Uganda<br />

Forest Absorbing Carbon dioxide Emissions<br />

Household<br />

World Conservation Union<br />

Indirect Use Values<br />

Kasanje Sub-county Development Plan<br />

Local Council<br />

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment<br />

<strong>Mabamba</strong> Bird Guides and Conservation Association<br />

<strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Wetland</strong> Eco-tourism Association<br />

Ministry <strong>of</strong> Water, Lands and Environment<br />

National Environment Management Authority<br />

Option Values<br />

Payment for Environmental Services<br />

Statistical Package for Social Sciences<br />

Total <strong>Economic</strong> Value<br />

Use Values<br />

Willingness to accept<br />

Willingness to pay<br />

Existence Values<br />

vii

Executive summary<br />

<strong>Wetland</strong> systems directly support millions <strong>of</strong> people and provide goods and services to the world<br />

outside the wetland. People use the wetland soils for agriculture, they catch wetland fish to eat,<br />

they cut wetland trees for timber and fuel wood and wetland reeds to make mats and to thatch<br />

ro<strong>of</strong>s. Direct use may also take the form <strong>of</strong> recreation, such as bird watching or sailing, or<br />

scientific study. Despite their importance, wetlands through out the world are being modified and<br />

reclaimed. <strong>Wetland</strong>s are being rapidly modified, converted, over-exploited and degraded in the<br />

interests <strong>of</strong> other more ‘productive’ land and resource management options which appear to yield<br />

much higher and more immediate pr<strong>of</strong>its. Dam construction, irrigation schemes, housing<br />

developments and industrial activities have all had devastating impacts on wetland integrity and<br />

status, and economic policies have <strong>of</strong>ten hastened these processes <strong>of</strong> wetland degradation and<br />

loss. At the same time conservation efforts have traditionally paid little attention to economic<br />

values − as a result it has <strong>of</strong>ten been hard to justify or sustain wetlands in economic terms, or for<br />

them to compete with other, <strong>of</strong>ten destructive, investments and land uses. Such concerns have led<br />

to an explosion <strong>of</strong> efforts to value natural ecosystems and the services they provide. <strong>Valuation</strong><br />

studies have considerably increased our knowledge <strong>of</strong> the value <strong>of</strong> ecosystems. <strong>Economic</strong><br />

valuation can provide a powerful tool for placing wetlands on the agendas <strong>of</strong> conservation and<br />

development decision makers. <strong>Economic</strong> valuation also aims to quantify the benefits (both<br />

marketed and non-marketed) that people obtain from the wetland ecosystem services. This makes<br />

them comparable with other sectors <strong>of</strong> the economy, when investments are being appraised,<br />

activities are planned, policies are formulated, or land and water resource use decisions are made.<br />

<strong>Wetland</strong> ecosystems not only generate valuable goods and services but also give rise to economic<br />

costs which include among others expenditures on the physical inputs associated with resource<br />

and ecosystem management, opportunity costs and economic losses to local communities arising<br />

from crop raiding wild animals. The establishment <strong>of</strong> protected areas precludes land and resource<br />

uses. Protected areas such as wetlands permit restricted resource utilization, and wholly prevent<br />

cultivation and grazing. Either <strong>of</strong> these losses represents the opportunity cost <strong>of</strong> biodiversity<br />

conservation in terms <strong>of</strong> economic activities (such as agriculture) foregone.<br />

In the light <strong>of</strong> this, a study was undertaken to assess the present economic value <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong><br />

wetland system <strong>of</strong> international importance, Wakiso district, Uganda. The study was done<br />

between October – December 2008. The main objectives <strong>of</strong> the study were: to assess the annual<br />

Total <strong>Economic</strong> Value (TEV) <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland system; and to determine the distribution<br />

<strong>of</strong> costs arising from wetland conservation and management. As part <strong>of</strong> achieving those<br />

objectives, a household survey using stratified random sampling technique was carried out in 5<br />

parishes surrounding <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland. Only heads <strong>of</strong> households were targeted in face to<br />

face interviews. A total <strong>of</strong> 320 households (representative sample <strong>of</strong> 3,777 households) were<br />

randomly interviewed. Other data collection methods included evaluation <strong>of</strong> relevant secondary<br />

data in the field <strong>of</strong> environmental economics, face to face discussions with stakeholders, focus<br />

group discussions and Benefit Transfer Method.<br />

Contingent valuation method (CVM) was to estimate the economic values <strong>of</strong> wetland ecosystem<br />

services which were non-marketable or whose market substitutes could not be found. CVM was<br />

specifically used to measure existence value, option values, indirect values and non-use values.<br />

People revealed their value for the benefits derived from a wetland through their WTP for those<br />

benefits. People also revealed their value for wetland benefits through their WTA compensation<br />

for foregoing the benefit. In the case <strong>of</strong> access to a resource, people revealed their values through<br />

viii

a WTP to prevent the loss <strong>of</strong> access and their WTA compensation to tolerate the loss. The CVM<br />

involved directly asking people in a household survey by presenting a payment card with<br />

different bids, how much they were WTP to secure better ecosystem services (benefits). People<br />

were also asked for the amount <strong>of</strong> compensation they would be WTA to give up specific<br />

environmental services. People were asked to state their WTP and WTA, contingent on a specific<br />

hypothetical scenario and description <strong>of</strong> wetland ecosystem services. As the contingent valuation<br />

study was part <strong>of</strong> the household survey, 320 households were interviewed, randomly drawn from<br />

5 parishes around <strong>Mabamba</strong> Ramsar Site.<br />

The data gathered in a household survey was then statistically analyzed using a computer<br />

program called Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), which was re-branded in 2009<br />

as Predictive Analysis S<strong>of</strong>tware (PASW). The analysis indicated; the mean house hold size <strong>of</strong> 5<br />

people, 68% <strong>of</strong> the households engaged in subsistence farming, an annual average household<br />

income <strong>of</strong> US$276, and mean daily household water consumption as 87 litres. The aggregate<br />

annual water consumption for all 3,777 households was estimated to be119, 249,333litres. Poultry<br />

was the most owned (12,200 chickens) livestock among households. It was found out that the<br />

monthly mean household WTP for ecosystem services stood at US$7.2 while the mean household<br />

WTA for loss <strong>of</strong> access to wetland goods and services was US$ 196 per month.<br />

According to the findings <strong>of</strong> the study, the following services and goods emanate from <strong>Mabamba</strong><br />

<strong>Bay</strong> wetland system: supply <strong>of</strong> water for domestic purposes, support wetland edge cultivation<br />

through provision <strong>of</strong> water, nutrients, source <strong>of</strong> fish for local consumption and commercial<br />

purposes, recreation and tourism, source <strong>of</strong> sand for construction purposes, support water-based<br />

transport and source <strong>of</strong> handcraft materials such as papyrus for making mats. Indirect ecosystem<br />

services identified included: carbon storage and sequestration, buffering Lake Victoria, playing<br />

an important hydrological role for waters entering Lake Victoria from the surrounding<br />

catchments, acting as a flood control for the surrounding shoreline and maintaining a steady<br />

discharge <strong>of</strong> water as well as supplementing the water supply to Lake Victoria. The TEV (direct,<br />

indirect, option, bequest and existence values) <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland in its present form was<br />

estimated as US$ 3,576,609 per annum which is an equivalent <strong>of</strong> Uganda Shillings<br />

6,437,896,200/= (N.B. by the time <strong>of</strong> the study, 1 US$ was trading 1,800 Uganda Shillings on the<br />

Ugandan foreign exchange market). The non-marketable ecosystem services were valued at US$<br />

326,333 per year, thereby constituting 8.9 % <strong>of</strong> the annual TEV. Some <strong>of</strong> the benefits were found<br />

to be <strong>of</strong> local, national or global importance. The beneficiaries <strong>of</strong> ecosystem services were found<br />

to be at the household, local community, district, national and international levels.<br />

Following the performance <strong>of</strong> contingent valuation survey, the opportunity costs as expressed<br />

through WTA were estimated as US$ 8,883,504 per year, which is Uganda Shillings<br />

15,990,307,200/=. Vervet monkeys, Sitatunga, Bush buck, guinea fowl and hippopotamus were<br />

widely reported as crop raiding wild animals from <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland. These wild animals<br />

raid agricultural field in the neighbouring resulting in to loss <strong>of</strong> income and crop yield to farmers.<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> the limitations <strong>of</strong> financial resources and time, the monetary costs associated with<br />

losses due to crop raiding animals were not estimated. There was not any annual public<br />

expenditure from the Government specifically dedicated to the management <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> wetland<br />

system. Therefore this study focused on only opportunity costs.<br />

To ensure better deliverance <strong>of</strong> ecosystem services; and improved management and conservation<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland system, the study came up with the following practical<br />

recommendations:<br />

1. Illegal sand mining activities be stopped and thereafter restoration measures undertaken<br />

in areas with sand mining activities and abandoned sand pits. This will repair the<br />

ix

environmental damage and eventually lead to restoration <strong>of</strong> ecosystem functions,<br />

attributes and processes.<br />

2. Environmental Impact Assessment should be mandatory for all future sand mining<br />

operations within the vicinity <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland. This will help avoid irreversible<br />

changes and serious damage to the wetland; and safeguard valuable resources, natural<br />

areas and ecosystem components.<br />

3. Local communities and their local leaders should be sensitized on policies and laws<br />

governing environment management in Uganda, conservation values <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong><br />

wetland, dangers <strong>of</strong> illegal activities such as hunting, setting fires and wetland edge<br />

farming; and also on the principles <strong>of</strong> Ramsar Convention.<br />

4. Motivation <strong>of</strong> local communities to conserve <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland ecosystem through<br />

<strong>of</strong>fering economic and financial incentives. Such as engaging local communities in<br />

ecologically sound and culturally acceptable tourism enterprises; and <strong>of</strong>fering grants or<br />

other financial incentives to private forest owners around <strong>Mabamba</strong> wetland as a<br />

motivation to conserve biodiversity in their forests.<br />

5. Need for stakeholders to assist local communities to develop alternative sources <strong>of</strong> the<br />

products currently taken from the wetland. Alternatives may include fish farming (pond<br />

aquaculture), bee-keeping, woodlots for fuel wood, income generating products e.g. fruit<br />

garden and medicinal gardens. This may in the long run reduce pressure on the wetland<br />

resources and ultimately lead to conservation <strong>of</strong> the wetland biodiversity.<br />

6. Because <strong>of</strong> the role played by <strong>Mabamba</strong> wetland in mitigating global warming (through<br />

sequestering and storage <strong>of</strong> carbon), Wakiso district local government and other key<br />

stakeholders like Nature Uganda can secure financial resources from international carbon<br />

markets such as the Clean Development mechanism under Kyoto protocol and World<br />

Bank Bio Carbon fund. Under carbon <strong>of</strong>fset and credit arrangements, highly<br />

industrialized countries can finance the conservation and management activities <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Mabamba</strong> wetland in exchange for the credit for the amount <strong>of</strong> carbon saved or<br />

sequestered.<br />

7. Management <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland system should be strengthened. This should<br />

among others include formulation <strong>of</strong> the site management plan to guide the management<br />

activities <strong>of</strong> the site, directing an annual public expenditure towards its (wetland)<br />

management and; incorporating mabamba wetland issues in to other development<br />

activities, policies and plans.<br />

x

Chapter 1: Introduction<br />

<strong>Wetland</strong>s are amongst the Earth’s most productive ecosystems. They have been described as ‘’the<br />

Kidneys <strong>of</strong> the landscape’’, because <strong>of</strong> the functions they perform in the hydrological and<br />

chemical cycles, and ‘’ biological supermarkets’’ because <strong>of</strong> the extensive food webs and rich<br />

biodiversity they support (Barbier et al., 1997) <strong>Wetland</strong> systems directly support millions <strong>of</strong><br />

people and provide goods and services to the world outside the wetland. People use the wetland<br />

soils for agriculture, they catch wetland fish to eat, they cut wetland trees for timber and fuel<br />

wood and wetland reeds to make mats and to thatch ro<strong>of</strong>s. Direct use may also take the form <strong>of</strong><br />

recreation, such as bird watching or sailing, or scientific study. Peat soils have preserved ancient<br />

remains <strong>of</strong> people and track ways which are <strong>of</strong> great interest to archaeologists.<br />

Freshwater wetlands have high conservation significance, supporting concentrated populations <strong>of</strong><br />

birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrate species. It has been estimated that<br />

fresh water wetlands hold more than 40% <strong>of</strong> the entire world’s species and 12% <strong>of</strong> all animal<br />

species. Individual wetlands can be extremely important in supporting high numbers <strong>of</strong> endemic<br />

species. In addition to their direct biodiversity significance, wetlands play a vital role in<br />

supporting hydrological functions, and therefore underpinning wider freshwater ecosystems<br />

(Schuyt, et al. 2004). The economic value <strong>of</strong> the world’s wetlands is estimated at US$70 billion<br />

per year. The largest economic values <strong>of</strong> the world’s wetlands are the hydrological services<br />

provided through flood control and water filtering. Other significant values include fishing,<br />

biodiversity, and sources <strong>of</strong> local water supply, materials and firewood. Schuyt, et al. 2004,<br />

reports that Charles River Basin wetlands in Massachusetts consist <strong>of</strong> 3,455 hectares <strong>of</strong> fresh<br />

water marsh and wooded swamps <strong>of</strong> which the benefits derived from these wetlands include flood<br />

control, amenity values, pollution reduction, water supply and recreation. The flood damage<br />

prevention and pollution control functions alone are worth US$65 million per annum.<br />

An evaluation study <strong>of</strong> the services provided by the Nakivubo wetland in Kampala revealed<br />

US$1.7 million a year. Most <strong>of</strong> this value was attributed to water treatment and purification<br />

services. In addition approximately US$ 100,000 was estimated to accrue from wetland goods<br />

and products through crop cultivation, papyrus harvesting, brick making, and fish farming<br />

(MWLE, 2001). In rural areas <strong>of</strong> Uganda, households engaged in papyrus harvesting are<br />

estimated to be deriving as much as US$ 200 a year from their wetland activities. In Uganda,<br />

approximately five million people depend directly on wetlands for their water supply. The daily<br />

water consumption is conservatively estimated at 50 million litres a day. At commercial prices for<br />

water in rural areas, this amounts to at least US$ 25 million a year. <strong>Wetland</strong>s contribute to water<br />

supply not only to neighbouring communities, but to most <strong>of</strong> the population - through<br />

groundwater recharging, water storage, water purification (MWLE, 2001).<br />

Despite its high value, biodiversity conservation also gives rise to economic costs as well as<br />

requiring expenditures on the physical inputs associated with resource and ecosystem<br />

management. The costs can also be opportunity costs to forego benefits/gains accruing from<br />

wetland ecosystem conservation and management or opportunity costs to tolerate costs associated<br />

with the existence <strong>of</strong> the wetland ecosystem. Problem animals (including vermin) from the<br />

wetland can be a menace to local communities living around. They (wild animals) can stray in to<br />

the adjacent community lands resulting in to among others; destruction <strong>of</strong> crops in the gardens,<br />

damage <strong>of</strong> property, injury to people or transmission <strong>of</strong> diseases to domestic livestock. This leads<br />

to loss <strong>of</strong> livelihood and income derived from agricultural production. The establishment <strong>of</strong><br />

protected areas precludes land and resource uses. Protected areas such as wetlands permit<br />

1

estricted resource utilisation, and wholly prevent cultivation and grazing. Either <strong>of</strong> these losses<br />

represents the opportunity cost <strong>of</strong> biodiversity conservation in terms <strong>of</strong> economic activities (such<br />

as agriculture) foregone.<br />

1.1 Justification for performing an economic valuation study<br />

Despite their importance, wetlands through out the world are being modified and reclaimed. It has<br />

been estimated that since 1900 more than half <strong>of</strong> the world’s wetlands have disappeared, largely<br />

through conversion to agricultural use. In the US, for example, 87% <strong>of</strong> wetland loss has been to<br />

agricultural development (Schuyt, et al. 2004). <strong>Wetland</strong>s however, provide numerous goods and<br />

services that have an economic value not only to the people who are living in the periphery <strong>of</strong> a<br />

wetland (in terms <strong>of</strong> water, fish, reeds and wildlife), but also to those living downstream<br />

(wetlands regulate water supply and recycle human wastes). A major factor contributing to the<br />

loss <strong>of</strong> wetlands is that decision-makers <strong>of</strong>ten have insufficient understanding <strong>of</strong> these economic<br />

values <strong>of</strong> these wetlands (Schuyt, et al. 2004).<br />

The value <strong>of</strong> wetlands and their associated ecosystem services has been estimated at US$14<br />

trillion annually. Yet many <strong>of</strong> these services, such as the recharge <strong>of</strong> ground water, water<br />

purification or aesthetic and cultural values are not immediately obvious when one looks at the<br />

wetland. Planners and decision-makers at many levels are frequently not fully aware <strong>of</strong> the<br />

connections between wetland condition and the provision <strong>of</strong> wetland services and the consequent<br />

benefits for the people, benefits which <strong>of</strong>ten have substantial economic value (De Groot et al.<br />

2006). Only in very few cases have decisions been informed by the TEV and benefits <strong>of</strong> both<br />

marketed and non-marketed services <strong>of</strong> wetlands. This lack <strong>of</strong> understanding and recognition <strong>of</strong><br />

the roles wetlands play, leads to ill-informed decisions on management and development, which<br />

contribute to the continued rapid loss, conversion and degradation <strong>of</strong> wetlands despite the TEV <strong>of</strong><br />

unconverted wetlands <strong>of</strong>ten being greater than that <strong>of</strong> converted wetlands.<br />

Infrastructure development activities have all had devastating impacts on wetland integrity and<br />

status, and economic policies have <strong>of</strong>ten hastened these processes <strong>of</strong> wetland degradation and<br />

loss. At the same time conservation efforts have traditionally paid little attention to economic<br />

values − as a result it has <strong>of</strong>ten been hard to justify or sustain wetlands in economic terms, or for<br />

them to compete with other, <strong>of</strong>ten destructive, investments and land uses. In fact, the problem is<br />

not that wetlands have no economic value, but rather that this value is poorly understood, rarely<br />

articulated, and as a result is frequently omitted from decision-making (Emerton, 2003).<br />

Although conventional analysis decrees that the ‘best’ or most efficient allocation <strong>of</strong> resources is<br />

one that maximizes economic returns, calculations <strong>of</strong> the returns to different land, resource and<br />

investment options have for the most part failed to deal adequately with wetland values.<br />

Investment appraisals <strong>of</strong> dams do not usually consider the economic costs attached to modifying<br />

downstream river flows and hydrology, the economic impacts <strong>of</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> wetland resources tends<br />

not to be factored into calculations <strong>of</strong> the potential pr<strong>of</strong>itability <strong>of</strong> land reclamation or conversion<br />

schemes, cost-benefit analyses <strong>of</strong> infrastructure projects have rarely incorporated estimates <strong>of</strong><br />

environmental benefits and costs (Emerton, 2003). Decisions have tended to be made on the basis<br />

<strong>of</strong> only partial information and have thus favoured short-term (and <strong>of</strong>ten unsustainable)<br />

development imperatives, or led to conservation regimes that generate few financial or economic<br />

benefits. In the absence <strong>of</strong> information about wetland values, substantial misallocation <strong>of</strong><br />

resources has occurred and gone unrecognised (Emerton, 2003) and immense economic costs<br />

have <strong>of</strong>ten been incurred. <strong>Economic</strong> valuation can provide a powerful tool for placing wetlands<br />

on the agenda <strong>of</strong> conservation and development decision-makers. Its basic aim is to determine<br />

2

people’s preferences: how much they are willing to pay for wetland goods and services, and how<br />

much better or worse <strong>of</strong>f they they would consider themselves to be as a result <strong>of</strong> changes in their<br />

supply.<br />

Such concerns have led to an explosion <strong>of</strong> efforts to value natural ecosystems and the services<br />

they provide (Emerton, 2003). <strong>Valuation</strong> studies have considerably increased our knowledge <strong>of</strong><br />

the value <strong>of</strong> ecosystems. <strong>Economic</strong> valuation can provide a powerful tool for placing wetlands on<br />

the agendas <strong>of</strong> conservation and development decision makers. <strong>Economic</strong> valuation also aims to<br />

quantify the benefits (both marketed and non-marketed) that people obtain from the wetland<br />

ecosystem services. This makes them comparable with other sectors <strong>of</strong> the economy, when<br />

investments are being appraised, activities are planned, policies are formulated, or land and water<br />

resource use decisions are made. It provides analytical basis for considering trade- <strong>of</strong>fs and<br />

making management decisions that better support public welfare and aspirations. More important,<br />

it is enables decision-makers and the public to evaluate the full economic costs and the benefits <strong>of</strong><br />

any proposed change in a wetland. A better understanding <strong>of</strong> the economic value <strong>of</strong> wetlands<br />

enables them to be considered as economically productive systems, a long side other possible<br />

uses <strong>of</strong> land, resources and funds. <strong>Valuation</strong> techniques are increasingly being used to generate<br />

practical management and policy information.<br />

An important objective <strong>of</strong> wetland valuation is to provide an improved basis for designing land<br />

and resource use policies and management systems (Barendregt et al 1998). Despite the steps<br />

forward that have been made in calculating and expressing the value <strong>of</strong> wetland goods and<br />

services, a major challenge remains − to ensure that the results <strong>of</strong> these studies, and the figures<br />

they generate, are actually fed into decision-making processes and used to influence conservation<br />

and development agendas.<br />

1.2 Rationale for evaluating benefits <strong>of</strong> wetland ecosystem conservation (adapted<br />

from De Groot, et al. 2006)<br />

More and better information on the socio-cultural and economic benefits <strong>of</strong> ecosystem<br />

services is needed to:<br />

i. Demonstrate the contribution <strong>of</strong> wetlands to the local, national and global<br />

economy (and thus build local and political support for their conservation and<br />

sustainable use);<br />

ii. Convince decision-makers that the benefits <strong>of</strong> conservation and sustainable use <strong>of</strong><br />

wetlands usually outweigh the costs and explain the need to better factor wetlands<br />

in to development planning (through more balanced cost-benefit analysis);<br />

iii. Identify the users and beneficiaries <strong>of</strong> wetland services to attract investments and<br />

secure sustainable financial streams and incentives for the maintenance, or<br />

restoration, <strong>of</strong> these services (i.e. make users pay and ensure that local people<br />

receive a proper share <strong>of</strong> the benefits); and<br />

iv. Increase awareness about the many benefits <strong>of</strong> wetlands to human well-being and<br />

ensure that wetlands are better taken in to account in economic welfare indicators<br />

(e.g., in Gross National Product (GNP) calculations) and pricing mechanisms<br />

(through internalization <strong>of</strong> externalities).<br />

3

1.3 The objectives <strong>of</strong> the study<br />

Overall objective<br />

The overall objective is to estimate the annual Total <strong>Economic</strong> Value (TEV) <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong><br />

wetland system in its present form i.e., to determine the total contribution <strong>of</strong> the ecosystem to the<br />

local or national economy and human well-being.<br />

The specific objectives <strong>of</strong> the economic valuation study were:<br />

i. To identify and quantify the benefits (both marketed and non-marketed) that people<br />

obtain from <strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland ecosystem<br />

ii.<br />

iii.<br />

iv.<br />

To assign monetary values to identified ecosystem goods and services produced by<br />

<strong>Mabamba</strong> <strong>Bay</strong> wetland system.<br />

To determine the annual TEV <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mabamba</strong> bay wetland ecosystem in its present form.<br />

Determine the opportunity costs <strong>of</strong> conserving <strong>Mabamba</strong> bay wetland in terms <strong>of</strong> benefits<br />

foregone and other economic activities<br />

4

2.1 <strong>Wetland</strong> conservation benefits<br />

Chapter 2: Literature review<br />

<strong>Wetland</strong> ecosystems, including rivers, lakes, marshes, rice fields, and coastal areas, provide many<br />

services that contribute to human well-being and poverty alleviation. Some groups <strong>of</strong> people,<br />

particularly those living near the wetlands, are highly dependent on these services and are directly<br />

harmed by their degradation (MA, 2005). <strong>Wetland</strong> services with strong linkages to human wellbeing<br />

include:<br />

Fish supply and water availability: Two <strong>of</strong> the most important wetland ecosystem services<br />

affecting human well-being involve fish supply and water availability. Inland fisheries are <strong>of</strong><br />

particular importance in developing countries, and are the primary source <strong>of</strong> animal protein to<br />

which rural communities have access. <strong>Wetland</strong>-related fisheries also make important<br />

contributions to local and national economies. Capture fisheries in coastal waters alone contribute<br />

$34 billion to growth world product annually. The principle supply <strong>of</strong> renewable fresh water for<br />

human use comes from an array <strong>of</strong> inland wetlands, including lakes, rivers, swamps, and<br />

swallows ground water aquifers. Groundwater, <strong>of</strong>ten recharged through wetlands, plays an<br />

important role in water supply, with an estimated 1.5-3 bilion people dependent on it as a source<br />

<strong>of</strong> drinking water.<br />

Water purification and detoxification <strong>of</strong> wastes: <strong>Wetland</strong>s, and in particular marshes, play a major<br />

role in treating and detoxifying a variety <strong>of</strong> waste products. Some wetlands have been found to<br />

have been found to reduce the concentration <strong>of</strong> nitrate by more than 80%. <strong>Wetland</strong>s also provide<br />

a vitally important, water treatment and purification (MA 2005). Large amounts <strong>of</strong> water enter the<br />

wetlands. The waste include: detergents, hidoricents, oil, acids, nitrates, phosphates and heavy<br />

metals. The wetlands treat and purify this water before it is passed onto the lake or connecting<br />

river (NEMA, 2007). <strong>Wetland</strong>s also provide important water purification services. Most urban<br />

populations in Uganda lack water-borne sewage systems and domestic wastes <strong>of</strong>ten flow directly<br />

into swamps and wetlands. It is estimated that at least 725,000 people rely on wetlands for waste<br />

retention and purification, including populations in Kampala, Bushenyi and Masaka Towns<br />

wetlands (MWLE, 2001). The value <strong>of</strong> wetland water purification and waste treatment services<br />

can be at least partially valued by looking at their replacement by other means. The cost <strong>of</strong><br />

establishing and maintaining a 4,000 m 3 sewage treatment pond, serving some 25,000 people is<br />

some US$ 0.15 million a year (Emerton et al, 1999). This translates into a total annual value for<br />

wetlands water purification services in terms <strong>of</strong> replacement cost avoided <strong>of</strong> some US$ 4.77<br />

million a year<br />

Climate regulation: One <strong>of</strong> the most important roles <strong>of</strong> wetlands may be in the regulation <strong>of</strong><br />

global climate change through sequestering and releasing a major proportion <strong>of</strong> fixed carbon in<br />

the biosphere. For example although covering only an estimated 3-4% <strong>of</strong> the world’s land area,<br />

peatlands are estimated to hold 540 gigatons <strong>of</strong> carbon, representing about 1.5% <strong>of</strong> the estimated<br />

global carbon storage and about 25-30% <strong>of</strong> what contained in terrestrial vegetation and soils<br />

(MA, 2005). <strong>Wetland</strong>s play a sometimes crucial role in regulating exchanges to/from the<br />

atmosphere <strong>of</strong> the naturally-produced gases involved in “greenhouse” effects, namely water<br />

vapour, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide (all associated with warming) and sulphur dioxide<br />

(associated with cooling). They tend to be sinks for carbon and nitrogen, and sources for methane<br />

and sulphur compounds, but situations vary widely from place to place, from time to time, and<br />

between (Pritchard, 2009)<br />

5

Mitigation <strong>of</strong> climate change impacts: Sea level rises and increases in storm surges associated<br />

with climate change will result in the erosion <strong>of</strong> shores and habitat, increased salinity <strong>of</strong> estuaries<br />

and freshwater aquifers, altered tidal ranges in rivers and bays, changes in sediment and nutrient<br />

transport, and increased coastal flooding and in turn, could increase the vulnerability <strong>of</strong> some<br />

coastal populations. <strong>Wetland</strong>s such as mangroves and floodplains can play a critical role in the<br />

physical buffering <strong>of</strong> climate change impacts.<br />

Cultural services: <strong>Wetland</strong>s provide significant aesthetic, educational, cultural and spiritual<br />

benefits, as well as a vast array <strong>of</strong> opportunities for recreation and tourism. Recreational fishing<br />

can generate considerable income: 35-45 million people take part in recreational fishing (inland<br />

and salt water) in the United States, spending a total <strong>of</strong> $24-37 billion each year on their hobby<br />

(MA, 2005). Much <strong>of</strong> the economic value <strong>of</strong> coral reefs – with net benefits estimated at nearly<br />

$30 billion each year – is generated from nature-based tourism, including scuba diving and<br />

snorkelling.<br />

Source <strong>of</strong> food, fiber, fuel and construction materials: Over 30,000 km 2 <strong>of</strong> Uganda is under<br />

seasonal or permanent wetlands. A wide variety <strong>of</strong> wetland plant species are harvested by<br />

adjacent human populations for food, medicine, construction material and handicraft production.<br />

Each hectare <strong>of</strong> papyrus swamp yields 20 tones <strong>of</strong> dry papyrus culm a year (Emerton et al., 1999 )<br />

with a market price for construction materials <strong>of</strong> USh 54/kg (US$ 0.036/Kg) giving a minimum<br />

value <strong>of</strong> papyrus utilization for Uganda <strong>of</strong> just under USh 6 billion (US$ 4 Million) a year.<br />

Natural vegetation in wetlands and floodplains also provides an important source <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>f-farm<br />

pasture, fodder and forage as dry season grazing for livestock Emerton et al, 1999 estimate the<br />

dry season grazing <strong>of</strong> wetlands vegetation in Uganda to be a total value in excess <strong>of</strong> UShs 18<br />

billion (US$ 12 million) a year in terms <strong>of</strong> contribution to livestock production. In Apac district,<br />

Uganda, the most common type <strong>of</strong> fish includes catfish, lung fish, tilapia and clarias observed in<br />

major wetlands. Fishing, especially <strong>of</strong> tilapia is common in all wetlands <strong>of</strong> the district with the<br />

greatest activity in the permanent wetlands.<br />

Water retention and purification by wetlands: <strong>Wetland</strong>s generate a wide range <strong>of</strong> indirect benefits<br />

through water recharge and storage, sediment trapping, nutrient cycling and water purification<br />

functions. <strong>Wetland</strong> ecosystem services also maintain and support <strong>of</strong>f-site water dependent<br />

consumption and production activities, including downstream resource utilization, industry and<br />

urban settlement. <strong>Wetland</strong>s water recharge, storage and productivity services permit on-site<br />

economic activities in addition to those which depend directly on the harvesting <strong>of</strong> wild<br />

resources, most importantly crop production. This crop output reflects wetland water retention<br />

and productivity maintenance services. The value <strong>of</strong> wetlands ecosystem functions as reflected in<br />

agricultural production is worth some US$ 44,000 (Emerton et al, 1999).<br />

Hydrological services: <strong>Wetland</strong>s deliver a wide range <strong>of</strong> hydrological services – for instance,<br />

swamps, lakes, and marshes assist with flood mitigation, promote ground water recharge, and<br />

regular river flows – but the nature and value <strong>of</strong> these services differs across wetland types.<br />

Mitigating floods: Many wetlands diminish the destructive nature <strong>of</strong> flooding, and the loss <strong>of</strong><br />

these wetlands increases the risks <strong>of</strong> floods occurring. <strong>Wetland</strong>s such as flood plains, lakes, and<br />

reservoirs are the main providers <strong>of</strong> flood attenuation potential in inland water systems. Nearly 2<br />

billion people live in areas <strong>of</strong> high flood risk – a risk that will be increased if wetlands are lost or<br />

degraded (MA 2005). Coastal wetlands, including coastal barrier islands, coastal rive floodplains,<br />

and coastal vegetation, all play an important role in reducing the impacts <strong>of</strong> flood waters<br />

produced by coastal storm events.<br />

6

Table 2-1: Summary <strong>of</strong> Ecosystem services derived from or provided by wetlands<br />

Services<br />

Comments and Examples<br />

a. Provisioning: products obtained from ecosystems<br />

Food<br />

production <strong>of</strong> fish, wild game, fruits, and grains<br />

Fresh water<br />

Fiber and fuel<br />

storage and retention <strong>of</strong> water for domestic,<br />

industrial, and agricultural use<br />

production <strong>of</strong> logs, fuel wood, peat, fodder<br />

Biochemical<br />

extraction <strong>of</strong> medicines and other materials<br />

from biota<br />

Genetic materials<br />

genes for resistance to plant pathogens,<br />

ornamental species, and so on<br />

b. Regulating: benefits obtained from regulation <strong>of</strong> ecosystem processes<br />

Climate regulation<br />

source <strong>of</strong> and sink for greenhouse gases;<br />

influence local and regional temperature,<br />

precipitation, and other climatic processes<br />

Water regulation (hydrological flows) groundwater recharge/discharge<br />

Water purification and waste treatment<br />

Erosion regulation<br />

Natural hazard regulation<br />

Pollination<br />

retention, recovery, and removal <strong>of</strong> excess<br />

nutrients and other pollutants<br />

retention <strong>of</strong> soils and sediments<br />

flood control, storm protection<br />

habitat for pollinators<br />

c. Cultural: non-material benefits obtained from ecosystems<br />

Spiritual and inspirational<br />

source <strong>of</strong> inspiration; many religions attach<br />

spiritual and religious values to aspects <strong>of</strong><br />

wetland ecosystems<br />

Recreational<br />

opportunities for recreational activities<br />

Aesthetic<br />

many people find beauty or aesthetic value in<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> wetland ecosystems<br />

Educational<br />

opportunities for formal and informal education<br />

and training<br />

d. Supporting: services necessary for the production <strong>of</strong> all other ecosystem services<br />

Soil formation<br />

sediment retention and accumulation <strong>of</strong> organic<br />

matter<br />

Nutrient cycling<br />

storage, recycling, processing, and acquisition<br />

<strong>of</strong> nutrients<br />

Source: Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005. Ecosystems and human well-being: <strong>Wetland</strong>s<br />

and water.<br />

7

Total <strong>Economic</strong> Value: a framework for defining wetland economic benefits<br />

One reason for the persistent under-valuation <strong>of</strong> wetlands is that, traditionally, concepts <strong>of</strong><br />

economic value have been based on a very narrow definition <strong>of</strong> benefits. Economists have seen<br />

the value <strong>of</strong> natural ecosystems only in terms <strong>of</strong> the raw materials and physical products that they<br />

generate for human production and consumption, especially focusing on commercial activities<br />

and pr<strong>of</strong>its. These direct uses however represent only a small proportion <strong>of</strong> the total value <strong>of</strong><br />

wetlands, which generate economic benefits far in excess <strong>of</strong> just physical or marketed products<br />

(Emerton, 2003). The concept <strong>of</strong> total economic value has now become one <strong>of</strong> the most widely<br />

used frameworks for identifying and categorizing ecosystem benefits (Barbier et al 1997). Instead<br />

<strong>of</strong> focusing only on direct commercial values, it also encompasses the subsistence and nonmarket<br />

values, ecological functions and non-use benefits associated with wetlands. As well as<br />

presenting a more complete picture <strong>of</strong> the economic importance <strong>of</strong> wetlands, it clearly<br />

demonstrates the high and wide-ranging economic costs associated with their degradation, which<br />

extends beyond the loss <strong>of</strong> direct use values.<br />

According to Pearce et al, 1994, conceptually Total <strong>Economic</strong> Value (TEV) <strong>of</strong> an environmental<br />

resource consists <strong>of</strong> its use value (UV) and non-use value (NUV). A use value is much as it<br />

sounds – a value arising from actual use made <strong>of</strong> a given resource. This might be the use <strong>of</strong> a<br />

wetland for recreation or fishing and so on. Use values are further divided in to direct use values<br />

(DUV), which refer to actual uses such as fishing, hunting, water extraction, harvesting <strong>of</strong><br />

papyrus plants etc; indirect use values (IUV), which refer to the benefits derived from ecosystem<br />

functions such as the wetlands function in regulating hydrological flows; and option values (OV),<br />

which is a value approximating an individual’s willingness to pay to safeguard an asset for the<br />

option <strong>of</strong> using it at a future date. This is like an insurance value. Non-use values (NUV) are<br />

slightly more problematic in definition and estimation, but are more usually divided between a<br />

bequest value (BV) and an existence or ‘passive use value (XV). Bequest value measures the<br />

benefits accruing to any individual from the knowledge that others may benefit from a resource in<br />

future. Existence values are unrelated to current use or option values, deriving simply from the<br />

existence <strong>of</strong> any particular asset. An individual’s concern to protect, say, the rare shoe-bill stork<br />

although he or she has never seen one and is never likely to, could be an example <strong>of</strong> existence<br />

value. Thus in total we have:<br />

TEV = UV + NUV = (DUV + IUV + OV) + (XV + BV)<br />

The total economic valuation framework, as applied to wetlands, is illustrated in Table 2.2<br />

8

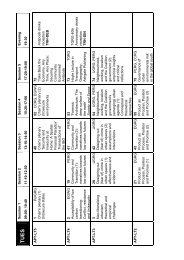

Table 2-2: Classification <strong>of</strong> total economic values for wetlands<br />

Use Values<br />

Non-Use Values<br />

Direct values Indirect values Option values Non-use values<br />

production and<br />

consumption<br />

goods and services<br />

such as . . .<br />

ecosystem functions<br />

and<br />

services<br />

such as . . .<br />

premium placed on<br />

possible future uses<br />

and<br />

applications<br />

intrinsic significance<br />

in terms <strong>of</strong> . . .<br />

such as . . .<br />

• fish<br />

• fuelwood<br />

• building poles<br />

• sand, gravel, clay<br />

• thatch<br />

• water<br />

• wild foods<br />

• medicines<br />

•agriculture/cultivation<br />

• pasture/grazing<br />

• transport<br />

• recreation<br />

• water quality<br />

• water flow<br />

• water storage<br />

• water purification<br />

• water recharge<br />

• flood control<br />

• storm protection<br />

• nutrient retention<br />

• micro-climate<br />

regulation<br />

• shore stabilization<br />

• pharmaceutical<br />

• agricultural<br />

• industrial<br />

• leisure<br />

• water use<br />

• cultural value<br />

• aesthetic value<br />

• heritage value<br />

• bequest value<br />

• existence value<br />

Source: MWLE, <strong>Wetland</strong> Strategic Plan, 2001-2010, Kampala, Uganda.<br />

2.2 <strong>Economic</strong> costs associated with wetland conservation<br />

Despite its high value, biodiversity conservation also gives rise to economic costs as well as<br />

requiring expenditures on the physical inputs associated with resource and ecosystem<br />

management, biodiversity incurs costs because it precludes or interferes with other economic<br />

activities. The economic costs can be:<br />

Management expenditures: This includes direct costs <strong>of</strong> implementing conservation measures<br />

such as staff, equipment, infrastructure, running costs and other physical inputs associated with<br />

managing biodiversity. They are incurred to government agencies, non-governmental<br />

organizations, community members and external donors<br />

Opportunity costs: Conserving ecosystems and the goods and services they provide may also<br />

involve foregoing certain uses <strong>of</strong> these ecosystems, and the benefits that would have been derived<br />

from those uses. Not converting a wetland ecosystem to agriculture, for example, preserves<br />

certain valuable ecosystem services that wetlands may provide better than farmland, but also<br />

prevents us from enjoying the benefits <strong>of</strong> agricultural production.<br />

Opportunity costs represent the income and other benefits foregone from land use, investment and<br />

development opportunities precluded or diminished by the need to maintain biodiversity. These<br />

include unsustainable resource and land utilization activities, production processes and<br />

technologies which harm or deplete biodiversity and alternative investments <strong>of</strong> funds allocated to<br />

biodiversity management. The opportunity costs <strong>of</strong> biodiversity can be in terms <strong>of</strong> agricultural<br />

production benefits foregone in protected areas in a year.<br />

9

Losses to other economic activities: represent the damage caused by biodiversity to human<br />

populations, production and consumption. They include damage, death and injury to humans,<br />

crops and livestock from wild animals, disease and other components <strong>of</strong> biodiversity which are<br />

harmful to or interfere with production and consumption processes. Damage caused to<br />

agriculture from wild animals comprises a major economic cost associated with Uganda’s<br />

biodiversity. Crop damage rates attributed to wildlife have been estimated to average some USh<br />

116 million per km <strong>of</strong> boundary for major protected areas in Uganda (Howard 1995, updated to<br />

1998 prices), giving a total economic cost in excess <strong>of</strong> USh 97 billion a year.<br />

2.3 Reasons why wetlands are still under-valued and over-used (adapted from<br />

Vorhies 1999; Stuip et al. 2002)<br />

<strong>Wetland</strong> values are <strong>of</strong>ten not taken in to account properly or fully in decision making, or are only<br />

partially valued, <strong>of</strong>ten leading to degradation or even destruction <strong>of</strong> a wetland.<br />

Market failure: public goods: Many <strong>of</strong> the ecological services, biological resources and amenity<br />

values provided by wetlands have the qualities <strong>of</strong> a public good; i.e. many wetland services are<br />

seen as ‘’free’’ and are thus not accounted for in the market (e.g., water-purification or floodprevention).<br />

Market failures: externalities: Another type <strong>of</strong> market failure occurs when markets do not reflect<br />

the full social costs or benefits <strong>of</strong> a change in availability <strong>of</strong> a good or a service (so-called<br />

externalities. For example, the price <strong>of</strong> agricultural products obtained from drained wetlands do<br />

not fully reflect the costs, in terms <strong>of</strong> pollution and lost wetland services, which are imposed upon<br />

society by the production process.<br />

Perverse incentives: (e.g., taxes/subsidies stimulating wetland over-use). Many policies and<br />

government decisions provide incentives for economic activity that <strong>of</strong>ten unintentionally work<br />

against the wise use <strong>of</strong> wetlands, leading to resource degradation and destruction rather than<br />

sustainable management (Vorhies 1999). An example might be subsidies for shrimp farmers<br />

leading to mangrove destruction.<br />

Unequal distribution <strong>of</strong> costs and benefits: Usually, those stakeholders who benefit from an<br />

ecosystem service, or its over-use, are not the same as the stakeholders who bear the cost. For<br />

example when a wetland is affected by pollution <strong>of</strong> the upper catchment by the run<strong>of</strong>f from<br />

agricultural land, the people living downstream <strong>of</strong> the wetland could suffer from this. The<br />

resulting loss <strong>of</strong> value (e.g., health, income) is not accounted for and the downstream stakeholders<br />

are generally not compensated for the damages they suffer (Stuip et al. 2002)<br />

No clear ownership: Ownership <strong>of</strong> wetlands can be difficult to establish. <strong>Wetland</strong>s ecosystems can<br />

be difficult to establish. <strong>Wetland</strong> ecosystems <strong>of</strong>ten do not have clear natural boundaries and, even<br />

when natural boundaries can be defined, they may not correspond with an administrative boundary.<br />

Therefore, their bounds <strong>of</strong> responsibility <strong>of</strong> a government organization cannot be easily allocated<br />

and user values are not apparent to decision makers.<br />

Devolution <strong>of</strong> decision-making away from local users and managers: Failure <strong>of</strong> decision-makers<br />

and planners to recognize the importance <strong>of</strong> wetlands to those who rely on them, either directly or<br />

indirectly.<br />

10

2.4 Solutions to correct externalities; and incentives to support the<br />

conservation and sustainable use <strong>of</strong> biodiversity<br />

Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES): Payments PES schemes have received considerable<br />

attention as a new way <strong>of</strong> approaching conservation. PES schemes are based on the principle that<br />

biodiversity provides a number <strong>of</strong> economically significant services: payments and funding<br />

should be therefore devoted to protecting biodiversity, thereby ensuring the continued provision<br />

<strong>of</strong> these services. The ecosystem services that have received the most attention are watershed<br />

protection and carbon sequestration (NEMA, 2007). Other environmental services include the<br />

maintenance <strong>of</strong> biodiversity and landscape beauty. In PES, those who are responsible for ensuring<br />

provision <strong>of</strong> ecosystem services receive payment or compensation to encourage future provision<br />

<strong>of</strong> the ecosystem services; and those who benefit from the ecosystem services provide the revenue<br />

for the payments. Where the collection <strong>of</strong> this revenue is linked to a fee on the use <strong>of</strong> the<br />

ecosystem services – for example a fee on water use – this can also create incentives for more<br />

efficient use <strong>of</strong> resources. PES can be in form <strong>of</strong> making user payments to a water fund, which is<br />

allocated to watershed protection, watershed restoration activities, and compensation to forest<br />

owners.<br />

Access charges: Access charges are a form <strong>of</strong> payment for environmental services and are based<br />

on the same principle: those who benefit from an ecosystem make payments towards the<br />

conservation and protection <strong>of</strong> the ecosystem. In case the case <strong>of</strong> access charges, charges are<br />

levied directly on those who use or visit an ecosystem, <strong>of</strong>ten visitors to the protected area or<br />

region. The funds raised by access charges can be used directly for conservation purposes and to<br />

generate socio-economic benefits for local communities, thereby providing local communities<br />

with incentives to preserve biodiversity.<br />

Creating markets that support conservation: Creating markets that support conservation involves<br />

ensuring that the returns to ecologically sound economic activity are increased when compared to<br />

the returns to unsustainable activity. Market-based approaches seek to utilize markets to reward<br />

ecologically sound activity. Local communities typically receive little direct gain from<br />

biodiversity products and areas to <strong>of</strong>fset the financial costs and losses they incur. Establishing and<br />

developing markets, and targeting the residents <strong>of</strong> biodiversity areas as participants in these<br />

markets, can provide an important tool for increasing community economic gain and control over<br />

biodiversity. The creation <strong>of</strong> biodiversity markets, as well as development <strong>of</strong> alternatives to<br />

biodiversity depleting sources <strong>of</strong> income and subsistence, can simultaneously strengthen local<br />

livelihoods and set in place local incentives for conservation (Emerton et al. 1999). There is great<br />

potential for the development <strong>of</strong> various biodiversity markets in Uganda, and the inclusion <strong>of</strong><br />

local communities are primary participants and beneficiaries. Of particular importance are smallscale<br />

biological resource processing and value-added cottage industries, the promotion <strong>of</strong> locallysourced<br />

products such as supplies <strong>of</strong> food, labour and other services to larger-scale production<br />

and tourism ventures. The development <strong>of</strong> products, markets, income and employment<br />

opportunities as alternatives to biodiversity-depleting activities can also provide an important tool<br />

for biodiversity conservation.<br />

Property rights: An important reason why local communities are unwilling to conserve<br />

biodiversity, and fail to benefit from it, is because they are excluded from using or managing land<br />

and biological resources. Property rights address this problem and include the whole or partial<br />

transfer <strong>of</strong> ownership, tenure, management or use over biological resources, areas and aspects <strong>of</strong><br />

conservation. They deal with the fact that market failures lack <strong>of</strong> consideration <strong>of</strong> the value <strong>of</strong><br />

biodiversity in prices, markets and economic decisions is due in part to the absence <strong>of</strong><br />

11

transferable, well-defined and secure rights over land and biological resources. When property<br />

rights are established, biodiversity markets and scarcity prices should emerge, permitting the<br />

owners and users <strong>of</strong> biological resources to benefit from conservation or be forced to bear the<br />

implications <strong>of</strong> degradation (Emerton et al. 1999. In Uganda, Property rights in wildlife, forestry<br />

and wetland sectors take the form <strong>of</strong> joint management, utilisation and partnership arrangements.<br />

Property rights provide a powerful economic tool for biodiversity conservation.<br />

Fiscal measures: budgetary measures that raise and allocate taxes and subsidies (for example the<br />

return <strong>of</strong> hunting revenues and taxes, through the Treasury, to wildlife conservation activities in<br />