A prolific painter of portraits before and after the French Revolution ...

A prolific painter of portraits before and after the French Revolution ...

A prolific painter of portraits before and after the French Revolution ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 302<br />

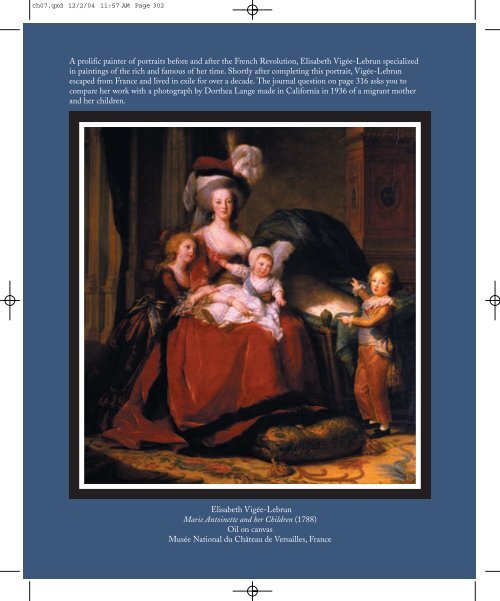

A <strong>prolific</strong> <strong>painter</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>portraits</strong> <strong>before</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>after</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>French</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong>, Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun specialized<br />

in paintings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rich <strong>and</strong> famous <strong>of</strong> her time. Shortly <strong>after</strong> completing this portrait, Vigée-Lebrun<br />

escaped from France <strong>and</strong> lived in exile for over a decade. The journal question on page 316 asks you to<br />

compare her work with a photograph by Dor<strong>the</strong>a Lange made in California in 1936 <strong>of</strong> a migrant mo<strong>the</strong>r<br />

<strong>and</strong> her children.<br />

Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun<br />

Marie Antoinette <strong>and</strong> her Children (1788)<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

Musée National du Château de Versailles, France

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 303<br />

chapter<br />

Explaining<br />

ou have decided to quit your present job, so you write a note to your boss<br />

giving thirty days’ notice. During your last few weeks at work, your<br />

boss asks you to write a three-page job description to help orient <strong>the</strong><br />

person who will replace you. The job description should include a list <strong>of</strong> your current<br />

duties as well as advice to your replacement on how to execute <strong>the</strong>m most efficiently.<br />

To write <strong>the</strong> description, you record your daily activities, look back through<br />

your calendar, comb through your records, <strong>and</strong> brainstorm a list <strong>of</strong> everything you<br />

do. As you write up <strong>the</strong> description, you include specific examples <strong>and</strong> illustrations<br />

<strong>of</strong> your typical responsibilities.<br />

s a gymnast <strong>and</strong> dancer, you gradually become obsessed with losing<br />

weight. You start skipping meals, purging <strong>the</strong> little food you do eat,<br />

<strong>and</strong> lying about your eating habits to your parents. Before long, you<br />

weigh less than seventy pounds, <strong>and</strong> your physician diagnoses your condition:<br />

anorexia nervosa. With advice from your physician <strong>and</strong> counseling from a psychologist,<br />

you gradually begin to control your disorder. To explain to o<strong>the</strong>rs what<br />

anorexia is, how it is caused, <strong>and</strong> what its effects<br />

are, you write an essay in which you explain your<br />

ordeal, alerting o<strong>the</strong>r readers to <strong>the</strong> potential<br />

dangers <strong>of</strong> uncontrolled dieting.<br />

‘‘<br />

Become aware <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> two-sided nature<br />

<strong>of</strong> your mental<br />

make-up: one<br />

thinks in terms <strong>of</strong><br />

he connectedness <strong>of</strong><br />

things, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

thinks in terms <strong>of</strong><br />

parts <strong>and</strong><br />

sequences.<br />

’’<br />

— GABRIELE LUSSER<br />

‘‘<br />

RICO,<br />

AUTHOR OF WRITING<br />

THE NATURAL WAY<br />

What [a writer]<br />

knows is almost<br />

always a matter <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> relationships he<br />

establishes, between<br />

example <strong>and</strong><br />

generalization,<br />

between one part <strong>of</strong> a<br />

narrative <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

next, between <strong>the</strong><br />

idea <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

counter idea that<br />

<strong>the</strong> writer sees is<br />

also relevant.<br />

’’<br />

— ROGER SALE,<br />

AUTHOR OF<br />

ON WRITING<br />

303

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 304<br />

304<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

XPLAINING AND DEMONSTRATING RELATIONSHIPS IS A FREQUENT PURPOSE<br />

BACKGROUND ON<br />

EXPLAINING<br />

This chapter assumes that<br />

expository writing <strong>of</strong>ten includes<br />

some mixture <strong>of</strong><br />

definition, process analysis,<br />

<strong>and</strong> causal analysis. Although<br />

a completed essay<br />

may use just one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se as<br />

a primary strategy, a writer<br />

needs a choice <strong>of</strong> expository<br />

strategies for <strong>the</strong><br />

thinking, learning, <strong>and</strong><br />

composing process.<br />

ESL TEACHING TIP<br />

Academic writing in <strong>the</strong><br />

United States is primarily<br />

expository writing, <strong>and</strong> it is<br />

culturally bound. Your ESL<br />

students may have very different<br />

expectations about<br />

<strong>the</strong> purpose, form, <strong>and</strong> style<br />

<strong>of</strong> academic writing. Discussing<br />

Robert Kaplan’s<br />

ideas about contrastive<br />

rhetoric—in class or in a<br />

conference—will allow your<br />

ESL students to underst<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> seemingly strange<br />

<strong>and</strong> arbitrary conventions<br />

<strong>of</strong> U.S. academic writing.<br />

FOR WRITING. EXPLAINING GOES BEYOND INVESTIGATING THE FACTS AND<br />

REPORTING INFORMATION; IT ANALYZES THE COMPONENT PARTS OF A SUBject<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n shows how <strong>the</strong> parts fit in relation to one ano<strong>the</strong>r. Its goal is to<br />

clarify for a particular group <strong>of</strong> readers what something is, how it happened<br />

or should happen, <strong>and</strong>/or why it happens.<br />

Explaining begins with assessing <strong>the</strong> rhetorical situation: <strong>the</strong> writer, <strong>the</strong> occasion,<br />

<strong>the</strong> intended purpose <strong>and</strong> audience, <strong>the</strong> genre, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> cultural context. As you<br />

begin thinking about a subject, topic, or issue to explain, keep in mind your own interests,<br />

<strong>the</strong> expectations <strong>of</strong> your audience, <strong>the</strong> possible genre you might choose to help<br />

achieve your purpose (essay, article, pamphlet, multigenre essay, Web site), <strong>and</strong> finally<br />

<strong>the</strong> cultural or social context in which you are writing or in which your writing might<br />

be read.<br />

Explaining any idea, concept, process, or effect requires analysis. Analysis starts<br />

with dividing a thing or phenomenon into its various parts. Then, once you explain<br />

<strong>the</strong> various parts, you put <strong>the</strong>m back toge<strong>the</strong>r (syn<strong>the</strong>sis) to explain <strong>the</strong>ir relationship<br />

or how <strong>the</strong>y work toge<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

Explaining how to learn to play <strong>the</strong> piano, for example, begins with an analysis<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> learning process: playing scales, learning chords, getting instruction<br />

from a teacher, sight reading, <strong>and</strong> performing in recitals. Explaining why two<br />

automobiles collided at an intersection begins with an analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> contributing<br />

factors: <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> intersection, <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> cars involved, <strong>the</strong> condition <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> drivers, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> condition <strong>of</strong> each vehicle. Then you bring <strong>the</strong> parts toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

<strong>and</strong> show <strong>the</strong>ir relationships: you show how practicing scales on <strong>the</strong> piano fits into<br />

<strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> learning to play <strong>the</strong> piano; you demonstrate why one small factor—<br />

such as a faulty turn signal—combined with o<strong>the</strong>r factors to cause an automobile accident.<br />

The emphasis you give to <strong>the</strong> analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> object or phenomenon <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

time you spend explaining relationships <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> parts depends on your purpose, subject,<br />

<strong>and</strong> audience. If you want to explain how a flower reproduces, for example, you<br />

may begin by identifying <strong>the</strong> important parts, such as <strong>the</strong> pistil <strong>and</strong> stamen, that<br />

most readers need to know about <strong>before</strong> <strong>the</strong>y can underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> reproductive<br />

process. However, if you are explaining <strong>the</strong> process to a botany major who already<br />

knows <strong>the</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> a flower, you might spend more time discussing <strong>the</strong> key operations<br />

in pollination or <strong>the</strong> reasons why some flowers cross-pollinate <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs do<br />

not. In any effective explanation, analyzing parts <strong>and</strong> showing relationships must<br />

work toge<strong>the</strong>r for that particular group <strong>of</strong> readers.<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 305<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

305<br />

Because its purpose is to teach <strong>the</strong> reader, expository writing, or writing to explain,<br />

should be as clear as possible. Explanations, however, are more than organized<br />

pieces <strong>of</strong> information. Expository writing contains information that is focused by your<br />

point <strong>of</strong> view, by your experience, <strong>and</strong> by your reasoning powers. Thus, your explanation<br />

<strong>of</strong> a thing or phenomenon makes a point or has a <strong>the</strong>sis: This is <strong>the</strong> right way<br />

to define happiness. This is how one should bake lasagne or do a calculus problem.<br />

These are <strong>the</strong> most important reasons why <strong>the</strong> senator from New York was elected.<br />

To make your explanation clear, you show what you mean by using specific support:<br />

facts, data, examples, illustrations, statistics, comparisons, analogies, <strong>and</strong> images.<br />

Your <strong>the</strong>sis is a general assertion about <strong>the</strong> relationships <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> specific parts. The support<br />

helps your reader identify <strong>the</strong> parts <strong>and</strong> see <strong>the</strong> relationships. Expository writing<br />

teaches <strong>the</strong> reader by alternating between generalizations <strong>and</strong> specific examples.<br />

Techniques for Explaining<br />

Explaining requires first that you assess your rhetorical situation. Your purpose must<br />

work for a particular audience, genre, <strong>and</strong> context. You may revise some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rhetorical situation as you draw on your own observations <strong>and</strong> memories<br />

about your topic. As you research your topic, conduct an interview, or do a survey,<br />

keep thinking about issues <strong>of</strong> audience, genre, <strong>and</strong> context. Below are techniques for<br />

writing clear explanations.<br />

‘‘<br />

The main thing<br />

I try to do is write as<br />

clearly as I can.<br />

’’<br />

— E . B . WHITE,<br />

JOURNALIST AND<br />

COAUTHOR OF<br />

ELEMENTS OF STYLE<br />

• Considering (<strong>and</strong> reconsidering) your purpose, audience, genre, <strong>and</strong> social<br />

context. As you change your audience or your genre, for example, you<br />

must change how you explain something as well as how much <strong>and</strong> what<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> evidence <strong>and</strong> support you use.<br />

• Getting <strong>the</strong> reader’s attention <strong>and</strong> stating <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>sis. Devise an accurate<br />

but interesting title. Use an attention-getting lead-in. State <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>sis<br />

clearly.<br />

• Defining key terms <strong>and</strong> describing what something is. Analyze <strong>and</strong> define<br />

by describing, comparing, classifying, <strong>and</strong> giving examples.<br />

• Identifying <strong>the</strong> steps in a process <strong>and</strong> showing how each step relates to<br />

<strong>the</strong> overall process. Describe how something should be done or how<br />

something typically happens.<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 306<br />

306<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

CRITICAL THINKING<br />

Students sometimes think<br />

that “critical thinking” is<br />

something that only teachers<br />

or expert writers do. Be<br />

sure to explain to students<br />

that <strong>the</strong> focus <strong>of</strong> this chapter<br />

is on analysis, which is<br />

at <strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong> critical<br />

thinking. Defining key<br />

terms, explaining <strong>the</strong> steps<br />

in a process, <strong>and</strong> analyzing<br />

causes <strong>and</strong> effects are essential<br />

to thinking critically<br />

<strong>and</strong> productively about any<br />

topic.<br />

Explaining what: Definition<br />

example<br />

Explaining why: Effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> projection<br />

Explaining how: <strong>the</strong><br />

process <strong>of</strong> freeing ourselves<br />

from dependency<br />

• Describing causes <strong>and</strong> effects <strong>and</strong> showing why certain causes lead to<br />

specific effects. Analyze how several causes lead to a single effect, or show<br />

how a single cause leads to multiple effects.<br />

• Supporting explanations with specific evidence. Use descriptions, examples,<br />

comparisons, analogies, images, facts, data, or statistics to show what,<br />

how, or why.<br />

In Spirit <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Valley: Androgyny <strong>and</strong> Chinese Thought, psychologist Sukie Colgrave<br />

illustrates many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se techniques as she explains an important concept from<br />

psychology: <strong>the</strong> phenomenon <strong>of</strong> projection. Colgrave explains how we “project” attributes<br />

missing in our own personality onto ano<strong>the</strong>r person—especially someone we<br />

love:<br />

A one-sided development <strong>of</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> masculine or feminine principles has<br />

[an] unfortunate consequence for our psychological <strong>and</strong> intellectual health:<br />

it encourages <strong>the</strong> phenomenon termed “projection.” This is <strong>the</strong> process by<br />

which we project onto o<strong>the</strong>r people, things, or ideologies, those aspects <strong>of</strong><br />

ourselves which we have not, for whatever reason, acknowledged or developed.<br />

The most familiar example <strong>of</strong> this is <strong>the</strong> obsession which usually accompanies<br />

being “in love.” A person whose feminine side is unrealised will<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten “fall in love” with <strong>the</strong> feminine which she or he “sees” in ano<strong>the</strong>r person,<br />

<strong>and</strong> similarly with <strong>the</strong> masculine. The experience <strong>of</strong> being “in love” is<br />

one <strong>of</strong> powerful dependency. As long as <strong>the</strong> projection appears to fit its object<br />

nothing awakens <strong>the</strong> person to <strong>the</strong> reality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> projection. But sooner<br />

or later <strong>the</strong> lover usually becomes aware <strong>of</strong> certain discrepancies between her<br />

or his desires <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> person chosen to satisfy <strong>the</strong>m. Resentment, disappointment,<br />

anger <strong>and</strong> rejection rapidly follow, <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>the</strong> relationship disintegrates....But<br />

if we can explore our own psyches we may discover what<br />

it is we were dem<strong>and</strong>ing from our lover <strong>and</strong> start to develop it in ourselves.<br />

The moment this happens we begin to see o<strong>the</strong>r people a little more clearly.<br />

We are freed from some <strong>of</strong> our needs to make o<strong>the</strong>rs what we want <strong>the</strong>m<br />

to be, <strong>and</strong> can begin to love <strong>the</strong>m more for what <strong>the</strong>y are.<br />

EXPLAINING WHAT<br />

Explaining what something is or means requires showing <strong>the</strong> relationship between<br />

it <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> class <strong>of</strong> beings, objects, or concepts to which it belongs. Formal definition,<br />

which is <strong>of</strong>ten essential in explaining, has three parts: <strong>the</strong> thing or term to be defined,<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 307<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

307<br />

<strong>the</strong> class, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> distinguishing characteristics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> thing or term. The thing being<br />

defined can be concrete, such as a turkey, or abstract, such as democracy.<br />

THING OR TERM CLASS DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS<br />

A turkey is a bird that has brownish plumage <strong>and</strong> a bare,<br />

wattled head <strong>and</strong> neck; it is widely<br />

domesticated for food.<br />

Democracy is government by <strong>the</strong> people, exercised directly or<br />

through elected representatives.<br />

Frequently, writers use extended definitions when <strong>the</strong>y need to give more than a<br />

mere formal definition. An extended definition may explain <strong>the</strong> word’s etymology<br />

or historical roots, describe sensory characteristics <strong>of</strong> something (how it looks, feels,<br />

sounds, tastes, smells), identify its parts, indicate how something is used, explain<br />

what it is not, provide an example <strong>of</strong> it, <strong>and</strong>/or note similarities or differences between<br />

this term <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r words or things.<br />

The following extended definition <strong>of</strong> democracy, written for an audience <strong>of</strong> college<br />

students to appear in a textbook, begins with <strong>the</strong> etymology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> word <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n<br />

explains—using analysis, comparison, example, <strong>and</strong> description—what democracy is<br />

<strong>and</strong> what it is not:<br />

TEACHING TIP<br />

Ask students to annotate<br />

<strong>the</strong> various techniques for<br />

extended definition illustrated<br />

in this paragraph on<br />

democracy. Their marginal<br />

notes might be as follows:<br />

Since democracy is government <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> people, by <strong>the</strong> people, <strong>and</strong> for <strong>the</strong><br />

people, a democratic form <strong>of</strong> government is not fixed or static. Democracy<br />

is dynamic; it adapts to <strong>the</strong> wishes <strong>and</strong> needs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> people. The term<br />

democracy derives from <strong>the</strong> Greek word demos, meaning “<strong>the</strong> common people,”<br />

<strong>and</strong> -kratia, meaning “strength or power” used to govern or rule.<br />

Democracy is based on <strong>the</strong> notion that a majority <strong>of</strong> people creates laws <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>n everyone agrees to abide by those laws in <strong>the</strong> interest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> common<br />

good. In a democracy, people are not ruled by a king, a dictator, or a small<br />

group <strong>of</strong> powerful individuals. Instead, people elect <strong>of</strong>ficials who use <strong>the</strong><br />

power temporarily granted to <strong>the</strong>m to govern <strong>the</strong> society. For example, <strong>the</strong><br />

people may agree that <strong>the</strong>ir government should raise money for defense, so<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficials levy taxes to support an army. If enough people decide, however,<br />

that taxes for defense are too high, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>y request that <strong>the</strong>ir elected<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficials change <strong>the</strong> laws or <strong>the</strong>y elect new <strong>of</strong>ficials. The essence <strong>of</strong> democracy<br />

lies in its responsiveness: Democracy is a form <strong>of</strong> government in which<br />

laws <strong>and</strong> lawmakers change as <strong>the</strong> will <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> majority changes.<br />

Formal definition<br />

Description: What<br />

democracy is<br />

Etymology: Analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> word’s roots<br />

Comparison: What<br />

democracy is not<br />

Example<br />

Formal definition<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 308<br />

308<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

Figurative expressions—vivid word pictures using similes, metaphors, or analogies—can<br />

also explain what something is. During World War II, for example, <strong>the</strong><br />

Writer’s War Board asked E. B. White (author <strong>of</strong> Charlotte’s Web <strong>and</strong> many New<br />

Yorker magazine essays, as well as o<strong>the</strong>r works) to provide an explanation <strong>of</strong> democracy.<br />

Instead <strong>of</strong> giving a formal definition or etymology, White responded with a<br />

series <strong>of</strong> imaginative comparisons showing <strong>the</strong> relationship between various parts <strong>of</strong><br />

American culture <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> concept <strong>of</strong> democracy:<br />

Surely <strong>the</strong> Board knows what democracy is. It is <strong>the</strong> line that forms on <strong>the</strong><br />

right. It is <strong>the</strong> don’t in Don’t Shove. It is <strong>the</strong> hole in <strong>the</strong> stuffed shirt through<br />

which <strong>the</strong> sawdust slowly trickles; it is <strong>the</strong> dent in <strong>the</strong> high hat. Democracy<br />

is <strong>the</strong> recurrent suspicion that more than half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> people are right more<br />

than half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> time. It is <strong>the</strong> feeling <strong>of</strong> privacy in <strong>the</strong> voting booths, <strong>the</strong><br />

feeling <strong>of</strong> communion in <strong>the</strong> libraries, <strong>the</strong> feeling <strong>of</strong> vitality everywhere.<br />

Democracy is <strong>the</strong> score at <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ninth. It is an idea which<br />

hasn’t been disproved yet, a song <strong>the</strong> words <strong>of</strong> which have not gone bad. It’s<br />

<strong>the</strong> mustard on <strong>the</strong> hot dog <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> cream in <strong>the</strong> rationed c<strong>of</strong>fee. Democracy<br />

is a request from a War Board, in <strong>the</strong> middle <strong>of</strong> a morning in <strong>the</strong> middle<br />

<strong>of</strong> a war, wanting to know what democracy is.<br />

Often, we think that explanations <strong>of</strong> technical subjects must be academic <strong>and</strong> complex,<br />

but sometimes writers about technical subjects use images <strong>and</strong> metaphors to get<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir point across. In <strong>the</strong> following definition <strong>of</strong> Web robots—so-called “bots,” Andrew<br />

Leonard, writing for a contemporary audience in Wired magazine, enlivens his<br />

explanation by personifying <strong>the</strong>se s<strong>of</strong>tware programs:<br />

Web robots—spiders, w<strong>and</strong>erers, <strong>and</strong> worms. Cancelbots, Lazarus, <strong>and</strong> Automoose.<br />

Chatterbots, s<strong>of</strong>t bots, userbots, taskbots, knowbots, <strong>and</strong> mailbots.<br />

. . . In current online parlance, <strong>the</strong> word “bot” pops up everywhere,<br />

flung around carelessly to describe just about any kind <strong>of</strong> computer program—a<br />

logon script, a spellchecker—that performs a task on a network.<br />

Strictly speaking, all bots are “autonomous”—able to react to <strong>the</strong>ir environments<br />

<strong>and</strong> make decisions without prompting from <strong>the</strong>ir creators; while<br />

<strong>the</strong> master or mistress is brewing c<strong>of</strong>fee, <strong>the</strong> bot is <strong>of</strong>f retrieving Web documents,<br />

exploring a MUD, or combatting Usenet spam. ...Even more<br />

important than function is behavior—bona fide bots are programs with<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 309<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

309<br />

personality. Real bots talk, make jokes, have feelings—even if those feelings<br />

are nothing more than cleverly conceived algorithms.<br />

EXPLAINING HOW<br />

Explaining how something should be done or how something happens is usually<br />

called process analysis. One kind <strong>of</strong> process analysis is <strong>the</strong> “how-to” explanation: how<br />

to cook a turkey, how to tune an engine, how to get a job. Such recipes or directions<br />

are prescriptive: You typically explain how something should be done. In a second<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> process analysis, you explain how something happens or is typically done—<br />

without being directive or prescriptive. In a descriptive process analysis, you explain<br />

how some natural or social process typically happens: how cells split during mitosis,<br />

how hailstones form in a cloud, how students react to <strong>the</strong> pressure <strong>of</strong> examinations,<br />

or how political c<strong>and</strong>idates create <strong>the</strong>ir public images. In both prescriptive <strong>and</strong><br />

descriptive explanations, however, you are analyzing a process—dividing <strong>the</strong> sequence<br />

into its parts or steps—<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n showing how <strong>the</strong> parts contribute to <strong>the</strong> whole<br />

process.<br />

Cookbooks, automobile-repair manuals, instructions for assembling toys or appliances,<br />

<strong>and</strong> self-improvement books are all examples <strong>of</strong> prescriptive process analysis.<br />

Writers <strong>of</strong> recipes, for example, begin with analyses <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ingredients <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

steps in preparing <strong>the</strong> food. Then <strong>the</strong>y carefully explain how <strong>the</strong> steps are related, how<br />

to avoid problems, <strong>and</strong> how to serve mouth-watering concoctions. Farley Mowat, naturalist<br />

<strong>and</strong> author <strong>of</strong> Never Cry Wolf, gives his readers <strong>the</strong> following detailed—<strong>and</strong><br />

humorous—recipe for creamed mouse. Mowat became interested in this recipe when<br />

he decided to test <strong>the</strong> nutritional content <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> wolf ’s diet. “In <strong>the</strong> event that any<br />

<strong>of</strong> my readers may be interested in personally exploiting this hi<strong>the</strong>rto overlooked<br />

source <strong>of</strong> excellent animal protein,” Mowat writes, “I give <strong>the</strong> recipe in full”:<br />

TEACHING TIP<br />

Explain that process analysis<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten contains two kinds<br />

<strong>of</strong> analyses: analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

ingredients, parts, or items<br />

used in <strong>the</strong> process <strong>and</strong><br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> chronology.<br />

In a recipe, for example, <strong>the</strong><br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> parts occurs in<br />

<strong>the</strong> list <strong>of</strong> ingredients; <strong>the</strong><br />

chronology is <strong>the</strong> instructions.<br />

Ask students to read<br />

<strong>the</strong> Mowat <strong>and</strong> Thomas<br />

excerpts for both kinds <strong>of</strong><br />

analyses. Then ask <strong>the</strong>m to<br />

apply both kinds <strong>of</strong> analyses,<br />

if appropriate, to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

own topics or drafts.<br />

INGREDIENTS:<br />

Souris à la Crème<br />

One dozen fat mice Salt <strong>and</strong> pepper One cup white flour<br />

Cloves One piece sowbelly Ethyl alcohol<br />

Skin <strong>and</strong> gut <strong>the</strong> mice, but do not remove <strong>the</strong> heads; wash, <strong>the</strong>n place in a<br />

pot with enough alcohol to cover <strong>the</strong> carcasses. Allow to marinate for about<br />

two hours. Cut sowbelly into small cubes <strong>and</strong> fry slowly until most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

fat has been rendered. Now remove <strong>the</strong> carcasses from <strong>the</strong> alcohol <strong>and</strong> roll<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 310<br />

310<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

<strong>the</strong>m in a mixture <strong>of</strong> salt, pepper <strong>and</strong> flour; <strong>the</strong>n place in frying pan <strong>and</strong><br />

sauté for about five minutes (being careful not to allow <strong>the</strong> pan to get too<br />

hot, or <strong>the</strong> delicate meat will dry out <strong>and</strong> become tough <strong>and</strong> stringy). Now<br />

add a cup <strong>of</strong> alcohol <strong>and</strong> six or eight cloves. Cover <strong>the</strong> pan <strong>and</strong> allow to<br />

simmer slowly for fifteen minutes. The cream sauce can be made according<br />

to any st<strong>and</strong>ard recipe. When <strong>the</strong> sauce is ready, drench <strong>the</strong> carcasses<br />

with it, cover <strong>and</strong> allow to rest in a warm place for ten minutes <strong>before</strong><br />

serving.<br />

CRITICAL READING<br />

Show students how writers<br />

use multiple strategies by<br />

asking <strong>the</strong>m to identify<br />

rhetorical strategies that<br />

Thomas uses in this excerpt.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> margins, have<br />

students identify at least<br />

one example to illustrate<br />

definition, process, <strong>and</strong><br />

causal strategies. If possible,<br />

connect this exercise to<br />

<strong>the</strong> students’ own writing.<br />

Model identification <strong>of</strong><br />

strategies with your own<br />

draft or with a sample piece<br />

<strong>of</strong> student writing. Then<br />

have students trade drafts<br />

or notes <strong>and</strong> have peer<br />

readers suggest how <strong>the</strong><br />

writer may combine several<br />

explaining strategies.<br />

Explaining how something happens or is typically done involves a descriptive<br />

process analysis. It requires showing <strong>the</strong> chronological relationship between one<br />

idea, event, or phenomenon <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> next—<strong>and</strong> it depends on close observation. In<br />

The Lives <strong>of</strong> a Cell, biologist <strong>and</strong> physician Lewis Thomas explains that ants are like<br />

humans: while <strong>the</strong>y are individuals, <strong>the</strong>y can also act toge<strong>the</strong>r to create a social organism.<br />

Although exactly how ants communicate remains a mystery,Thomas explains<br />

how <strong>the</strong>y combine to form a thinking, working organism:<br />

[Ants] seem to live two kinds <strong>of</strong> lives: <strong>the</strong>y are individuals, going about <strong>the</strong><br />

day’s business without much evidence <strong>of</strong> thought for tomorrow, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y<br />

are at <strong>the</strong> same time component parts, cellular elements, in <strong>the</strong> huge,<br />

writhing, ruminating organism <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill, <strong>the</strong> nest, <strong>the</strong> hive. . . .<br />

A solitary ant, afield, cannot be considered to have much <strong>of</strong> anything<br />

on his mind; indeed, with only a few neurons strung toge<strong>the</strong>r by fibers,<br />

he can’t be imagined to have a mind at all, much less a thought. He is<br />

more like a ganglion on legs. Four ants toge<strong>the</strong>r, or ten, encircling a<br />

dead moth on a path, begin to look more like an idea. They fumble <strong>and</strong><br />

shove, gradually moving <strong>the</strong> food toward <strong>the</strong> Hill, but as though by blind<br />

chance. It is only when you watch <strong>the</strong> dense mass <strong>of</strong> thous<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> ants,<br />

crowded toge<strong>the</strong>r around <strong>the</strong> Hill, blackening <strong>the</strong> ground, that you begin<br />

to see <strong>the</strong> whole beast, <strong>and</strong> now you observe it thinking, planning, calculating.<br />

It is an intelligence, a kind <strong>of</strong> live computer, with crawling bits for<br />

its wits.<br />

At a stage in <strong>the</strong> construction, twigs <strong>of</strong> a certain size are needed, <strong>and</strong><br />

all <strong>the</strong> members forage obsessively for twigs <strong>of</strong> just this size. Later, when<br />

outer walls are to be finished, thatched, <strong>the</strong> size must change, <strong>and</strong> as though<br />

given new orders by telephone, all <strong>the</strong> workers shift <strong>the</strong> search to <strong>the</strong> new<br />

twigs. If you disturb <strong>the</strong> arrangement <strong>of</strong> a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill, hundreds <strong>of</strong> ants<br />

will set it vibrating, shifting, until it is put right again. Distant sources <strong>of</strong><br />

food are somehow sensed, <strong>and</strong> long lines, like tentacles, reach out over <strong>the</strong><br />

ground, up over walls, behind boulders, to fetch it in.<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 311<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

311<br />

EXPLAINING WHY<br />

“Why?” may be <strong>the</strong> question most commonly asked by human beings. We are fascinated<br />

by <strong>the</strong> reasons for everything that we experience in life. We ask questions<br />

about natural phenomena: Why is <strong>the</strong> sky blue? Why does a teakettle whistle? Why<br />

do some materials act as superconductors? We also find human attitudes <strong>and</strong> behavior<br />

intriguing: Why is chocolate so popular? Why do some people hit small<br />

lea<strong>the</strong>r balls with big sticks <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n run around a field stomping on little white pillows?<br />

Why are America’s family farms economically depressed? Why did <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States go to war in Iraq? Why is <strong>the</strong> Internet so popular?<br />

Explaining why something occurs can be <strong>the</strong> most fascinating—<strong>and</strong> difficult—<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> expository writing. Answering <strong>the</strong> question “why” usually requires analyzing<br />

cause-<strong>and</strong>-effect relationships. The causes, however, may be too complex or<br />

intangible to identify precisely. We are on comparatively secure ground when we ask<br />

why about physical phenomena that can be weighed, measured, <strong>and</strong> replicated under<br />

laboratory conditions. Under those conditions, we can determine cause <strong>and</strong> effect<br />

with precision.<br />

Fire, for example, has three necessary <strong>and</strong> sufficient causes: combustible material,<br />

oxygen, <strong>and</strong> ignition temperature. Without each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se causes, fire will not<br />

occur (each cause is “necessary”); taken toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>se three causes are enough to<br />

cause fire (all three toge<strong>the</strong>r are “sufficient”). In this case, <strong>the</strong> cause-<strong>and</strong>-effect relationship<br />

can be illustrated by an equation:<br />

CAUSE 1 + CAUSE 2 + CAUSE 3 = EFFECT<br />

(combustible (oxygen) (ignition (fire)<br />

material)<br />

temperature)<br />

Analyzing both necessary <strong>and</strong> sufficient causes is essential to explaining an effect.<br />

You may say, for example, that wind shear (an abrupt downdraft in a storm)<br />

“caused” an airplane crash. In fact, wind shear may have contributed (been necessary)<br />

to <strong>the</strong> crash but was not by itself <strong>the</strong> total (sufficient) cause <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> crash: an airplane<br />

with enough power may be able to overcome wind shear forces in certain circumstances.<br />

An explanation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> crash is not complete until you analyze <strong>the</strong> full range<br />

<strong>of</strong> necessary <strong>and</strong> sufficient causes, which may include wind shear, lack <strong>of</strong> power, mechanical<br />

failure, <strong>and</strong> even pilot error.<br />

Sometimes, explanations for physical phenomena are beyond our analytical powers.<br />

Astrophysicists, for example, have good <strong>the</strong>oretical reasons for believing that<br />

WRITE TO LEARN<br />

Write-to-learn activities<br />

don’t have to be connected<br />

to a specific reading or text<br />

assignment. Any time you<br />

are giving instructions or<br />

discussing a point <strong>and</strong> hear<br />

yourself saying, “Does<br />

everyone underst<strong>and</strong> that?”<br />

or “Does anyone have a<br />

question?” stop <strong>and</strong> give<br />

students one or two minutes<br />

to write down <strong>the</strong><br />

main point <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> discussion<br />

or to write down two<br />

questions about it. Such<br />

write-to-learn activities<br />

give every student a chance<br />

to respond actively <strong>and</strong> give<br />

feedback to <strong>the</strong> teacher<br />

about students’ questions<br />

<strong>and</strong> ideas.<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 312<br />

312<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

black holes cause gigantic gravitational whirlpools in outer space, but <strong>the</strong>y have difficulty<br />

explaining why black holes exist—or whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y exist at all.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> realm <strong>of</strong> human cause <strong>and</strong> effect, determining causes <strong>and</strong> effects can be<br />

as tricky as explaining why black holes exist. Why, for example, do some children learn<br />

math easily while o<strong>the</strong>rs fail? What effect does failing at math have on a child? What<br />

are necessary <strong>and</strong> sufficient causes for divorce? What are <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> divorce on parents<br />

<strong>and</strong> children? Although you may not be able to explain all <strong>the</strong> causes or effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> something, you should not be satisfied until you have considered a wide range <strong>of</strong><br />

possible causes <strong>and</strong> effects. Even <strong>the</strong>n, you need to qualify or modify your statements,<br />

using such words as might, usually, <strong>of</strong>ten, seldom, many, or most, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n giving<br />

as much support <strong>and</strong> evidence as you can.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> following paragraphs, Jonathan Kozol, a critic <strong>of</strong> America’s educational<br />

system <strong>and</strong> author <strong>of</strong> Illiterate America, explains <strong>the</strong> multiple effects <strong>of</strong> a single cause:<br />

illiteracy. Kozol supports his explanation by citing specific ways that illiteracy affects<br />

<strong>the</strong> lives <strong>of</strong> people:<br />

Illiterates cannot read <strong>the</strong> menu in a restaurant.<br />

They cannot read <strong>the</strong> cost <strong>of</strong> items on <strong>the</strong> menu in <strong>the</strong> window <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

restaurant <strong>before</strong> <strong>the</strong>y enter.<br />

Illiterates cannot read <strong>the</strong> letters that <strong>the</strong>ir children bring home from<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir teachers. They cannot study school department circulars that tell <strong>the</strong>m<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> courses that <strong>the</strong>ir children must be taking if <strong>the</strong>y hope to pass <strong>the</strong><br />

SAT exams. They cannot help with homework. They cannot write a letter<br />

to <strong>the</strong> teacher. They are afraid to visit in <strong>the</strong> classroom. They do not want<br />

to humiliate <strong>the</strong>ir child or <strong>the</strong>mselves. . . .<br />

Many illiterates cannot read <strong>the</strong> admonition on a pack <strong>of</strong> cigarettes.<br />

Nei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> Surgeon General’s warning nor its reproduction on <strong>the</strong> package<br />

can alert <strong>the</strong>m to <strong>the</strong> risks. Although most people learn by word <strong>of</strong><br />

mouth that smoking is related to a number <strong>of</strong> grave physical disorders, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

do not get <strong>the</strong> chance to read <strong>the</strong> detailed stories which can document this<br />

danger with <strong>the</strong> vividness that turns concern into determination to resist.<br />

They can see <strong>the</strong> h<strong>and</strong>some cowboy or <strong>the</strong> slim Virginia lady lighting up a<br />

filter cigarette; <strong>the</strong>y cannot heed <strong>the</strong> words that tell <strong>the</strong>m that this product<br />

is (not “may be”) dangerous to <strong>the</strong>ir health. Sixty million men <strong>and</strong> women<br />

are condemned to be <strong>the</strong> unalerted, high-risk c<strong>and</strong>idates for cancer....<br />

Illiterates cannot travel freely. When <strong>the</strong>y attempt to do so, <strong>the</strong>y encounter<br />

risks that few <strong>of</strong> us can dream <strong>of</strong>. They cannot read traffic signs <strong>and</strong>,<br />

while <strong>the</strong>y <strong>of</strong>ten learn to recognize <strong>and</strong> to decipher symbols, <strong>the</strong>y cannot<br />

manage street names which <strong>the</strong>y haven’t seen <strong>before</strong>. The same is true for<br />

bus <strong>and</strong> subway stops. While ingenuity can sometimes help a man or<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 313<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

313<br />

woman to discern directions from familiar l<strong>and</strong>marks, buildings, cemeteries,<br />

churches, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> like, most illiterates are virtually immobilized. They<br />

seldom w<strong>and</strong>er past <strong>the</strong> streets <strong>and</strong> neighborhoods <strong>the</strong>y know. Geographical<br />

paralysis becomes a bitter metaphor for <strong>the</strong>ir entire existence. They are<br />

immobilized in almost every sense we can imagine. They can’t move up.<br />

They can’t move out. They cannot see beyond.<br />

Warming Up: Journal Exercises<br />

The following exercises will help you practice writing explanations. Read all <strong>of</strong><br />

t <strong>the</strong> following exercises <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n write on <strong>the</strong> three that interest you most.<br />

If ano<strong>the</strong>r idea occurs to you, write about it.<br />

1. Write a one-paragraph explanation <strong>of</strong> an idea, term, or concept that you<br />

have discussed in a class that you are currently taking. From biology, for example,<br />

you might define photosyn<strong>the</strong>sis or gene splicing. From psychology, you<br />

might define psychosis or projection. From computer studies, you might define<br />

cyberspace or morphing. First, identify someone who might need to<br />

know about this subject. Then give a definition <strong>and</strong> an illustration. Finally,<br />

describe how <strong>the</strong> term was discovered or invented, what its effects or applications<br />

are, <strong>and</strong>/or how it works.<br />

2. Imitating E. B. White’s short “definition” <strong>of</strong> democracy, use imaginative<br />

comparisons to write a short definition—serious or humorous—<strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> following words: freedom, adolescence, ma<strong>the</strong>matics, politicians, parents,<br />

misery, higher education, luck, or a word <strong>of</strong> your own choice.<br />

3. Novelist Ernest Hemingway once defined courage as “grace under pressure.”<br />

Using this definition, explain how you or someone you know showed this<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> courage in a difficult situation.<br />

4. When asked what jazz is, Louis Armstrong replied, “Man, if you gotta ask<br />

you’ll never know.” If you know quite a bit about jazz, explain what Armstrong<br />

meant. Or choose a familiar subject to which <strong>the</strong> same remark might<br />

apply. What can be “explained” about that subject, <strong>and</strong> what cannot?<br />

5. Choose a skill that you’ve acquired (for example, playing a musical instrument,<br />

operating a machine, playing a sport, drawing, counseling o<strong>the</strong>rs, driving<br />

in rush-hour traffic, dieting) <strong>and</strong> explain to a novice how he or she can<br />

acquire that skill. Reread what you’ve written. Then write ano<strong>the</strong>r version<br />

addressed to an expert. What parts can you leave out? What must you add?<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 314<br />

314<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

6. Sometimes writers use st<strong>and</strong>ard definitions to explain a key term, but sometimes<br />

<strong>the</strong>y need to resist conventional definition in order to make a point.<br />

LaMer Steptoe, an eleventh-grader in West Philadelphia, was faced with a<br />

form requiring her to check her racial identity. Like many Americans <strong>of</strong> multicultural<br />

heritage, she decided not to check one box. In <strong>the</strong> following paragraphs,<br />

reprinted from National Public Radio’s All Things Considered, Ms.<br />

Steptoe explains how she decided to (re)define herself. As you read her response,<br />

consider how you might need to resist a conventional definition in<br />

your own explaining essay.<br />

Multiracialness<br />

Caucasian, African-American, Latin American, Asian-American.<br />

Check one. I look black, so I’ll pick that one. But, no, wait, if I pick<br />

that, I’ll be denying <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r sides <strong>of</strong> my family. So I’ll pick white. But<br />

I’m not white or black, I’m both, <strong>and</strong> part Native American, too. It’s<br />

confusing when you have to pick which race to identify with, especially<br />

when you have family who, on one side, ask, “Why do you talk like a<br />

white girl?” when, in <strong>the</strong> eyes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r side <strong>of</strong> your family, your<br />

behind is black.<br />

I never met my dad’s mom, my gr<strong>and</strong>mo<strong>the</strong>r, Maybelle Dawson Boyd<br />

Steptoe, <strong>and</strong> my fa<strong>the</strong>r never knew his fa<strong>the</strong>r. But my aunts or uncles<br />

or cousins all think <strong>of</strong> me as black or white. I mean, I’m not <strong>the</strong><br />

lightest-skinned person, but my cousins down South swear I’m white.<br />

It bo<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>and</strong> that bo<strong>the</strong>rs me, how people could care so much<br />

about your skin color.<br />

My mo<strong>the</strong>r’s mo<strong>the</strong>r, Sylvia Gabriel, lives in Connecticut, near where<br />

my aunt, uncle <strong>and</strong> cousins on that side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> family live. Now, <strong>the</strong>y’re<br />

white, <strong>and</strong> where my gr<strong>and</strong>ma lives, <strong>the</strong>re are very few black people<br />

or people <strong>of</strong> color. And when we visit, people look at us a lot, staring<br />

like, “What is that woman doing with those people?” It shocks <strong>the</strong><br />

heck out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m when my bro<strong>the</strong>r <strong>and</strong> I call her Gr<strong>and</strong>ma.<br />

My mo<strong>the</strong>r’s side is Italian. I really didn’t get any Italian culture except<br />

for <strong>the</strong> food. My fa<strong>the</strong>r was raised much differently from my<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>r. My fa<strong>the</strong>r is superstitious; he believes that a child should<br />

know his or her place <strong>and</strong> not speak unless spoken to. My fa<strong>the</strong>r is very<br />

much into both his African-American <strong>and</strong> Native American heritage.<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 315<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

315<br />

Multiracialness is a very tricky subject for my fa<strong>the</strong>r. He’ll tell people that<br />

I’m Native, African-American <strong>and</strong> Caucasian American, but at <strong>the</strong><br />

same time he’ll say things like, “Listen to jazz, listen to your cultural<br />

music.” He says,“LaMer, look in <strong>the</strong> mirror. You’re black. Ask any white<br />

person: <strong>the</strong>y’ll say you’re black.” He doesn’t get it. I really would ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

be colorless than to pick a race. I like o<strong>the</strong>r music, not just black music.<br />

The term African-American bugs me. I’m not African. I’m American<br />

as a hot dog. We should have friends who are yellow, red, blue, black,<br />

purple, gay, religious, bisexual, trilingual, whatever, so you don’t have<br />

a stereotypical view. I’ve met mean people <strong>and</strong> nice people <strong>of</strong> all different<br />

backgrounds. At my school, I grew up with all <strong>the</strong>se kids, <strong>and</strong><br />

I didn’t look at <strong>the</strong>m as white or Jewish or heterosexual; I looked at<br />

<strong>the</strong>m as, “Oh, she’s funny, he’s sweet.”<br />

I know what box I’m going to choose. I pick D for none <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> above,<br />

because my race is human.<br />

Lange, Doro<strong>the</strong>a, photographer, “Migrant Agricultural Worker’s Family.” February<br />

1936. America from <strong>the</strong> Great Depression to World War II: Black-<strong>and</strong>-White Photographs<br />

from <strong>the</strong> FSA-OWI, 1935–1945, Library <strong>of</strong> Congress.<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 316<br />

316<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

7. Use your explaining skills to analyze visual images. For example, <strong>the</strong> work <strong>of</strong><br />

art that opens this chapter is Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun’s 1788 portrait <strong>of</strong><br />

Marie Antoinette <strong>and</strong> her Children. Use your browser to search for information<br />

about Marie Antoinette, her role in <strong>the</strong> <strong>French</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

career <strong>of</strong> Vigée-Lebrun. Then study <strong>the</strong> photograph on <strong>the</strong> previous page <strong>of</strong><br />

a migrant woman <strong>and</strong> her children, taken in California in 1936. Do some<br />

Internet research on Doro<strong>the</strong>a Lange <strong>and</strong> her series <strong>of</strong> photographs <strong>of</strong> migrant<br />

workers in California. Write an essay comparing <strong>and</strong> contrasting <strong>the</strong><br />

artists (Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun <strong>and</strong> Doro<strong>the</strong>a Lange), <strong>the</strong> composition <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se two images, <strong>and</strong>/or <strong>the</strong> social/cultural conditions surrounding each<br />

image. Assume that your audience is a group <strong>of</strong> your peers in your composition<br />

class.<br />

PROFESSIONAL WRITING<br />

Miss Clairol’s “Does She . . .<br />

Or Doesn’t She?”:<br />

How to Advertise a<br />

Dangerous Product<br />

James B. Twitchell<br />

A longtime pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> English at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Florida, James B. Twitchell<br />

has written a dozen books on a variety <strong>of</strong> academic <strong>and</strong> cultural topics. His recent<br />

books on advertising <strong>and</strong> popular culture include Carnival Culture: The<br />

Trashing <strong>of</strong> Taste in America (1992), Adcult USA: The Triumph <strong>of</strong> Advertising<br />

in American Culture (1996), <strong>and</strong> Living It Up: Our Love Affair<br />

with Luxury (2002). In “Miss Clairol’s ‘Does She ...Or Doesn’t She?’ ” taken<br />

from Twenty Ads That Shook <strong>the</strong> World (2000), Twitchell examines <strong>the</strong> Miss<br />

Clairol advertising campaign, which was designed by Shirley Polyk<strong>of</strong>f. Twitchell<br />

explains how Polyk<strong>of</strong>f ’s ads, which ran for nearly twenty years, revolutionized<br />

<strong>the</strong> hair-coloring industry. Part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> success <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ad was in <strong>the</strong> catchy title,<br />

Twitchell notes, but equally important were <strong>the</strong> children in <strong>the</strong> ads <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> followup<br />

phrase, “Hair color so natural, only her hairdresser knows for sure.” (Before you<br />

read Twitchell’s essay, however, look at several <strong>of</strong> Polyk<strong>of</strong>f ’s Clairol ads by searching<br />

Shirley Polyk<strong>of</strong>f on Google.)<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE<br />

1

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 317<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

317<br />

Two types <strong>of</strong> product are difficult to advertise: <strong>the</strong> very common <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> very<br />

radical. Common products, called “parity products,” need contrived distinctions<br />

to set <strong>the</strong>m apart. You announce <strong>the</strong>m as “New <strong>and</strong> Improved, Bigger<br />

<strong>and</strong> Better.” But singular products need <strong>the</strong> illusion <strong>of</strong> acceptability. They<br />

have to appear as if <strong>the</strong>y were not new <strong>and</strong> big, but old <strong>and</strong> small.<br />

So, in <strong>the</strong> 1950s, new objects like television sets were designed to look<br />

like furniture so that <strong>the</strong>y would look “at home” in your living room. Meanwhile,<br />

accepted objects like automobiles were growing massive tail fins to<br />

make <strong>the</strong>m seem bigger <strong>and</strong> better, new <strong>and</strong> improved.<br />

Although hair coloring is now very common (about half <strong>of</strong> all American<br />

women between <strong>the</strong> ages <strong>of</strong> thirteen <strong>and</strong> seventy color <strong>the</strong>ir hair, <strong>and</strong><br />

about one in eight American males between thirteen <strong>and</strong> seventy does <strong>the</strong><br />

same), such was certainly not <strong>the</strong> case generations ago. The only women<br />

who regularly dyed <strong>the</strong>ir hair were actresses like Jean Harlow, <strong>and</strong> “fast<br />

women,” most especially prostitutes. The only man who dyed his hair was<br />

Gorgeous George, <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional wrestler. He was also <strong>the</strong> only man to<br />

use perfume.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> twentieth century, prostitutes have had a central role in developing<br />

cosmetics. For <strong>the</strong>m, sexiness is an occupational necessity, <strong>and</strong> hence<br />

anything that makes <strong>the</strong>m look young, flushed, <strong>and</strong> fertile is quickly assimilated.<br />

Creating a full-lipped, big-eyed, <strong>and</strong> rosy-cheeked image is <strong>the</strong><br />

basis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lipstick, eye shadow, mascara, <strong>and</strong> rouge industries. While fashion<br />

may come down from <strong>the</strong> couturiers, face paint comes up from <strong>the</strong><br />

street. Yesterday’s painted woman is today’s fashion plate.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> 1950s, just as Betty Friedan was sitting down to write The Feminine<br />

Mystique, <strong>the</strong>re were three things a lady should not do. She should not<br />

smoke in public, she should not wear long pants (unless under an overcoat),<br />

<strong>and</strong> she should not color her hair. Better she should pull out each<br />

gray str<strong>and</strong> by its root than risk association with those who bleached or,<br />

worse, dyed <strong>the</strong>ir hair.<br />

This was <strong>the</strong> cultural context into which Lawrence M. Gelb, a chemical<br />

broker <strong>and</strong> enthusiastic entrepreneur, presented his product to Foote,<br />

Cone & Belding. Gelb had purchased <strong>the</strong> rights to a <strong>French</strong> hair-coloring<br />

process called Clairol. The process was unique in that unlike o<strong>the</strong>r available<br />

hair-coloring products, which coated <strong>the</strong> hair, Clairol actually penetrated<br />

<strong>the</strong> hair shaft, producing s<strong>of</strong>ter, more natural tones. Moreover, it contained<br />

a foamy shampoo base <strong>and</strong> mild oils that cleaned <strong>and</strong> conditioned <strong>the</strong> hair.<br />

When <strong>the</strong> product was first introduced during World War II, <strong>the</strong><br />

application process took five different steps <strong>and</strong> lasted a few hours. The<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 318<br />

318<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

TEACHING TIP<br />

Twitchell does a good job<br />

<strong>of</strong> analyzing <strong>the</strong> historical<br />

<strong>and</strong> cultural forces at work<br />

behind <strong>the</strong> Miss Clairol<br />

ads. Have students also<br />

practice analyzing <strong>the</strong><br />

composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> visual<br />

images in <strong>the</strong> Clairol ads<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Polyk<strong>of</strong>f Web site.<br />

Specifically, how does <strong>the</strong><br />

composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> images<br />

support (or add additional<br />

information to) Twitchell’s<br />

<strong>the</strong>sis that <strong>the</strong> Polyk<strong>of</strong>f<br />

campaign successfully<br />

managed <strong>the</strong> problems <strong>of</strong> a<br />

“dangerous product” being<br />

advertised to a complex<br />

audience?<br />

users were urban <strong>and</strong> wealthy. In 1950, <strong>after</strong> seven years <strong>of</strong> research <strong>and</strong><br />

development, Gelb once again took <strong>the</strong> beauty industry by storm. He introduced<br />

<strong>the</strong> new Miss Clairol Hair Color Bath, a single-step haircoloring<br />

process.<br />

This product, unlike any haircolor previously available, lightened, darkened,<br />

or changed a woman’s natural haircolor by coloring <strong>and</strong> shampooing<br />

hair in one simple step that took only twenty minutes. Color results were<br />

more natural than anything you could find at <strong>the</strong> corner beauty parlor. It<br />

was hard to believe. Miss Clairol was so technologically advanced that<br />

demonstrations had to be done onstage at <strong>the</strong> International Beauty Show,<br />

using buckets <strong>of</strong> water, to prove to <strong>the</strong> industry that it was not a hoax. This<br />

breakthrough was almost too revolutionary to sell.<br />

In fact, within six months <strong>of</strong> Miss Clairol’s introduction, <strong>the</strong> number<br />

<strong>of</strong> women who visited <strong>the</strong> salon for permanent hair-coloring services increased<br />

by more than 500 percent! The women still didn’t think <strong>the</strong>y could<br />

do it <strong>the</strong>mselves. And Good Housekeeping magazine rejected hair-color advertising<br />

because <strong>the</strong>y too didn’t believe <strong>the</strong> product would work. The magazine<br />

waited for three years <strong>before</strong> finally reversing its decision, accepting<br />

<strong>the</strong> ads, <strong>and</strong> awarding Miss Clairol’s new product <strong>the</strong> “Good Housekeeping<br />

Seal <strong>of</strong> Approval.”<br />

FC&B passed <strong>the</strong> “Yes you can do it at home” assignment to Shirley<br />

Polyk<strong>of</strong>f, a zesty <strong>and</strong> genial first-generation American in her late twenties.<br />

She was, as she herself was <strong>the</strong> first to admit, a little unsophisticated, but<br />

her colleagues thought she understood how women would respond to abrupt<br />

change. Polyk<strong>of</strong>f understood emotion, all right, <strong>and</strong> she also knew that you<br />

could be outrageous if you did it in <strong>the</strong> right context. You can be very<br />

naughty if you are first perceived as being nice. Or, in her words, “Think it<br />

out square, say it with flair.” And it is just this reconciliation <strong>of</strong> opposites<br />

that informs her most famous ad.<br />

She knew this almost from <strong>the</strong> start. On July 9, 1955, Polyk<strong>of</strong>f wrote<br />

to <strong>the</strong> head art director that she had three campaigns for Miss Clairol Hair<br />

Color Bath. The first shows <strong>the</strong> same model in each ad, but with slightly<br />

different hair color. The second exhorts “Tear up those baby pictures! You’re<br />

a redhead now,” <strong>and</strong> plays on <strong>the</strong> American desire to refashion <strong>the</strong> self by<br />

rewriting history. These two ideas were, as she says, “knock-downs” en route<br />

to what she really wanted. In her autobiography, appropriately titled Does<br />

She ...Or Doesn’t She?: And How She Did It, Polyk<strong>of</strong>f explains <strong>the</strong> third execution,<br />

<strong>the</strong> one that will work:<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

11<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 319<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

319<br />

#3. Now here’s <strong>the</strong> one I really want. If I can get it sold to <strong>the</strong> client.<br />

Listen to this: “Does she ...or doesn’t she?” (No, I’m not kidding. Didn’t<br />

you ever hear <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> arresting question?) Followed by: “Only her mo<strong>the</strong>r<br />

knows for sure!” or “So natural, only her mo<strong>the</strong>r knows for sure!”<br />

I may not do <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r part, though as far as I’m concerned<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>r is <strong>the</strong> ultimate authority. However, if Clairol goes retail, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

may have a problem <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fending beauty salons, where <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

presently doing all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir business. So I may change <strong>the</strong> word<br />

“mo<strong>the</strong>r” to “hairdresser.” This could be awfully good business—turning<br />

<strong>the</strong> hairdresser into a color expert. Besides, it reinforces <strong>the</strong> claim<br />

<strong>of</strong> naturalness, <strong>and</strong> not so incidentally, glamorizes <strong>the</strong> salon.<br />

The psychology is obvious. I know from myself. If anyone admires<br />

my hair, I’d ra<strong>the</strong>r die than admit I dye. And since I feel so<br />

strongly that <strong>the</strong> average woman is me, this great stress on naturalness<br />

is important [Polyk<strong>of</strong>f 1975, 28–29].<br />

While her headline is naughty, <strong>the</strong> picture is nice <strong>and</strong> natural. Exactly<br />

what “Does She . . . or Doesn’t She” do? To men <strong>the</strong> answer was clearly sexual,<br />

but to women it certainly was not. The male editors <strong>of</strong> Life magazine<br />

balked about running this headline until <strong>the</strong>y did a survey <strong>and</strong> found out<br />

women were not filling in <strong>the</strong> ellipsis <strong>the</strong> way <strong>the</strong>y were.<br />

Women, as Polyk<strong>of</strong>f knew, were finding different meaning because<br />

<strong>the</strong>y were actually looking at <strong>the</strong> model <strong>and</strong> her child. For <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong> picture<br />

was not presexual but postsexual, not inviting male attention but expressing<br />

satisfaction with <strong>the</strong> result. Miss Clairol is a mo<strong>the</strong>r, not a love interest.<br />

If that is so, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> product must be misnamed: it should be Mrs.<br />

Clairol. Remember, this was <strong>the</strong> mid-1950s, when illegitimacy was a powerful<br />

taboo. Out-<strong>of</strong>-wedlock children were still called bastards, not love<br />

children. This ad was far more dangerous than anything Benetton or Calvin<br />

Klein has ever imagined.<br />

The naught/nice conundrum was fur<strong>the</strong>r intensified <strong>and</strong> diffused by<br />

some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ads featuring a wedding ring on <strong>the</strong> model’s left h<strong>and</strong>. Although<br />

FC&B experimented with models purporting to be secretaries,<br />

schoolteachers, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> like, <strong>the</strong> motif <strong>of</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r <strong>and</strong> child was always constant.<br />

So what was <strong>the</strong> answer to what she does or doesn’t do? To women,<br />

what she did had to do with visiting <strong>the</strong> hairdresser. Of course, men couldn’t<br />

12<br />

13<br />

14<br />

15<br />

16<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 320<br />

320<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>. This was <strong>the</strong> world <strong>before</strong> unisex hair care. Men still went<br />

to barber shops. This was <strong>the</strong> same pre-feminist generation in which <strong>the</strong><br />

solitary headline “Modess . . . because” worked magic selling female sanitary<br />

products. The ellipsis masked a knowing implication that excluded<br />

men. That was part <strong>of</strong> its attraction. Women know, men don’t. This youjust-don’t-get-it<br />

motif was to become a central marketing strategy as <strong>the</strong><br />

women’s movement was aided <strong>and</strong> exploited by Madison Avenue<br />

nichemeisters.<br />

Polyk<strong>of</strong>f had to be ambiguous for ano<strong>the</strong>r reason. As she notes in her<br />

memo, Clairol did not want to be obvious about what <strong>the</strong>y were doing to<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir primary customer—<strong>the</strong> beauty shop. Remember that <strong>the</strong> initial product<br />

entailed five different steps performed by <strong>the</strong> hairdresser, <strong>and</strong> lasted<br />

hours. Many women were still using hairdressers for something <strong>the</strong>y could<br />

now do by <strong>the</strong>mselves. It did not take a detective to see that <strong>the</strong> company<br />

was trying to run around <strong>the</strong> beauty shop <strong>and</strong> sell to <strong>the</strong> end-user. So <strong>the</strong><br />

ad again has it both ways. The hairdresser is invoked as <strong>the</strong> expert—only<br />

he knows for sure—but <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> coloring your hair can be done without<br />

his expensive assistance.<br />

The copy block on <strong>the</strong> left <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> finished ad reasserts this intimacy,<br />

only now it is not <strong>the</strong> hairdresser speaking, but ano<strong>the</strong>r woman who has used<br />

<strong>the</strong> product. The emphasis is always on returning to young <strong>and</strong> radiant hair,<br />

hair you used to have, hair, in fact, that glistens exactly like your current<br />

companion’s—your child’s hair.<br />

The copy block on <strong>the</strong> right is all business <strong>and</strong> was never changed<br />

during <strong>the</strong> campaign. The process <strong>of</strong> coloring is always referred to as<br />

“automatic color tinting.” Automatic was to <strong>the</strong> fifties what plastic became<br />

to <strong>the</strong> sixties, <strong>and</strong> what networking is today. Just as your food was kept<br />

automatically fresh in <strong>the</strong> refrigerator, your car had an automatic transmission,<br />

your house had an automatic <strong>the</strong>rmostat, your dishes <strong>and</strong> clo<strong>the</strong>s<br />

were automatically cleaned <strong>and</strong> dried, so, too, your hair had automatic<br />

tinting.<br />

However, what is really automatic about hair coloring is that once you<br />

start, you won’t stop. Hair grows, roots show, buy more product . . . automatically.<br />

The genius <strong>of</strong> Gillette was not just that <strong>the</strong>y sold <strong>the</strong> “safety<br />

razor” (<strong>the</strong>y could give <strong>the</strong> razor away), but that <strong>the</strong>y also sold <strong>the</strong> concept<br />

<strong>of</strong> being clean-shaven. Clean-shaven means that you use <strong>the</strong>ir blade every<br />

day, so, <strong>of</strong> course, you always need more blades. Clairol made “roots showing”<br />

into what Gillette had made “five o’clock shadow.”<br />

17<br />

18<br />

19<br />

20<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 321<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

321<br />

As was to become typical in hair-coloring ads, <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> model was<br />

a good ten years younger than <strong>the</strong> typical product user. The model is in her<br />

early thirties (witness <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> child), too young to have gray hair.<br />

This aspirational motif was picked up later for o<strong>the</strong>r Clairol products:<br />

“If I’ve only one life . . . let me live it as a blonde!” “Every woman should<br />

be a redhead . . . at least once in her life!” “What would your husb<strong>and</strong> say<br />

if suddenly you looked 10 years younger?” “Is it true blondes have more<br />

fun?” “What does he look at second?” And, <strong>of</strong> course, “The closer he gets<br />

<strong>the</strong> better you look!”<br />

But <strong>the</strong>se slogans for different br<strong>and</strong> extensions only work because<br />

Miss Clairol had done her job. She made hair coloring possible, she made<br />

hair coloring acceptable, she made at-home hair coloring—dare I say it—<br />

empowering. She made <strong>the</strong> unique into <strong>the</strong> commonplace. By <strong>the</strong> 1980s,<br />

<strong>the</strong> hairdresser problem had been long forgotten <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> follow-up lines<br />

read, “Hair color so natural, <strong>the</strong>y’ll never know for sure.”<br />

The Clairol <strong>the</strong>me propelled sales 413 percent higher in six years <strong>and</strong><br />

influenced nearly 50 percent <strong>of</strong> all adult women to tint <strong>the</strong>ir tresses. Ironically,<br />

Miss Clairol, bought out by Bristol-Myers in 1959, also politely<br />

opened <strong>the</strong> door to her competitors, L’Oreal <strong>and</strong> Revlon.<br />

Thanks to Clairol, hair coloring has become a very attractive business<br />

indeed. The key ingredients are just a few pennies’ worth <strong>of</strong> peroxide, ammonia,<br />

<strong>and</strong> pigment. In a pretty package at <strong>the</strong> drugstore it sells for four to<br />