Japanese Prints

Japanese Prints

Japanese Prints

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

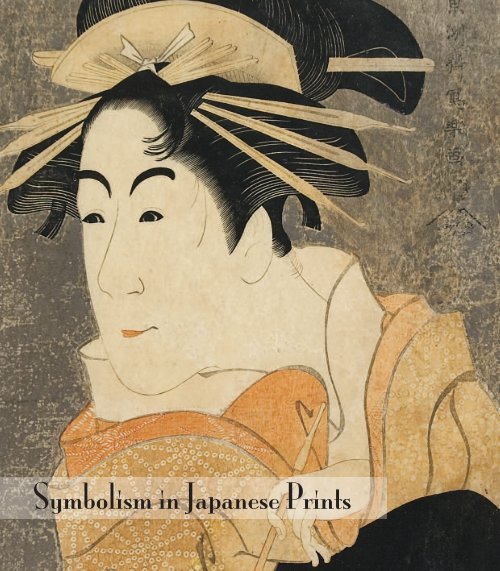

Symbolism in <strong>Japanese</strong> <strong>Prints</strong>

2<br />

The Mysterious Sharaku<br />

Although Toshusai Sharaku was a master of the <strong>Japanese</strong> woodcut art form, his true identity represents<br />

one of the great mysteries of the art world. Little is known about him, besides his Ukiyo-e, floating world<br />

prints. Even more improbably, Sharaku’s active career as a woodblock artist lasted a mere ten months,<br />

from the middle of 1794 to early 1795. He emerged out of nowhere, already with his own style, signalling<br />

a complete and immediate departure from all other <strong>Japanese</strong> artists of the period. He then disappeared with<br />

equal abruptness.<br />

This exceptional and very rare woodblock print by Sharaku depicts the Kabuki actor Matsumoto Yonezaburo<br />

in the role of Keisei Shiratama, one of two sisters whose father is murdered and becomes a courtesan<br />

in order to obtain revenge on the assassin. The serious expression in her eyes reveals that she is lost in deep<br />

contemplation as she smokes a pipe. This highly exaggerated portrait of the kabuki actor was executed in<br />

the great Sharaku’s characteristic style. The print bears the artist signature, Toshusai Sharaku Ga, and publisher<br />

seal on the top right of the image.<br />

As is typical of Sharaku, he used a ground known as unmo, or mica, which is a mineral contained in large<br />

amounts in granite. He sprinkled this on the paper to create an unusual silver-black or purple sheen in the<br />

background.<br />

One theory is that Sharaku was not an individual, but a collective launched by a group of artists to help a<br />

woodblock print-house that had aided them. The name Sharaku is taken from sharakusai, “nonsense,” and<br />

may be an inside joke by the artists, who knew that there was no individual of that name. In his short career<br />

Sharaku went through four distinct stylistic changes, lending credence to the claim that he was a collective<br />

rather than an individual. At this time it was quite common for five to ten artisans to work together on woodblock<br />

prints.<br />

It has been suggested that the great printmaker, Katsushika Hokusai, author of the iconic print The Great<br />

Wave of Kanagawa is the man behind Sharaku. Between 1792 and 1796, the time when Sharaku’s work<br />

starts to appear, Hokusai disappeared from the art world. However, there is little evidence to support this<br />

theory, other than explaining Hokusai’s absence from the art scene. The name of Jurōbei Saitō, a samurai<br />

turned Noh actor, has also been put forward however there is now some doubt around this theory.<br />

The mystery surrounding this artist, the rarity of his prints and his unusual technique and elegant style has<br />

helped to secure his place in <strong>Japanese</strong> art history as one of the most prominent and important artists.

Henry Sotheran Limited 3<br />

1. Kabuki Actor Matsumoto Yonezaburo Playing the Role of Keisei Shiratama. Sharaku (active 1794-1795). Original woodblock<br />

print, Japan, 1794-1795. 370 x 248mm. £69,000

4<br />

LAndScApES<br />

2<br />

3<br />

2. Suzukawa. Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950), 1935. 175 x<br />

275mm. £1,680<br />

3. Mountains of Komagatake. Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950),<br />

1928. 245 x 380mm. £1,650

Henry Sotheran Limited 5<br />

4<br />

5<br />

4. Mount Fuji from Yoshida. Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950), 1926.<br />

245 x 380mm. £1,200<br />

5. Mount Fuji from Yamanaka. Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950),<br />

1937. 245 x 380mm. £2,350

6<br />

LAndScApES<br />

6 7<br />

8 9<br />

6. Mount Fuji and Pine Tree. Koitsu Tsuchiya (1870-1949), early<br />

20th c. 240 x 360mm. £350<br />

7. View of Mount Fuji from Hakone. Hiroaki Takahashi (1871-<br />

1945), 1920. 240 x 360mm. £170<br />

8. Mountain over Pine Forest. Koichi Okumura (1904-1974), 20th<br />

c. 245 x 365mm. £250<br />

9. Mountain at Sunset. Imao Keisho (1902-1993), 20th c. 335 x<br />

380mm. £650

Henry Sotheran Limited 7<br />

10<br />

11 12<br />

10. Early Spring in Azumino.Toshi Yoshida (1911-1995), 20th c.<br />

220 x 320mm. £500<br />

11. Mt Fuji and Lake Kawaguchi. Okada Kouichi, 20th c. 360 x<br />

240mm. £225<br />

12. Mount Fuji after Snow. Hasui Kawase (1883-1957), 20th c.<br />

365 x 240mm. £2,550

8<br />

LAndScApES<br />

13<br />

14<br />

13. Nocturne Blue and Gold. After James Whistler (1834 - 1903),<br />

c.1910. 255 x 190mm. £450<br />

14. Boat with Lantern, under a Pine Tree at Taro-inari Shrine,<br />

Asakusa. Kiyochika Kobayashi (1847-1915), c.1910. 248 x<br />

180mm. £220

Henry Sotheran Limited 9<br />

16<br />

15<br />

15. High Bridge and Sailing boat.Yoshimune Arai (1873-1945),<br />

c.1920. 256 x 190mm. £180<br />

16. Torii Gate with Lanterns at Miyajima in the Rain. Hasui<br />

Kawase (1883-1957), 1941. 390 x 260mm. £850

10<br />

LAndScApES<br />

17 18 19<br />

20 21 22<br />

17. Futamigaura Sacred Rocks with Ropes. Koho Shoda (1871-<br />

1946), c.1920. 255 x 190mm. £290<br />

18. Kokedera (Moss Temple) Gate. Masao Maeda (1904-1974),<br />

1965. 485 x 390mm. £450<br />

19. Path with Torii Gate in the Full Moon. Kiyochika Kobayashi<br />

(1847-1915), c.1910. 250 x 190mm. £220<br />

20. Bamboo of the Summer. Shiro Kasmatsu (1898-1992), 20th<br />

c. 365 x 240mm. £180<br />

21. Pagoda in the Woods.Yuhan Ito (1882-1951), c.1920. 370 x<br />

255mm. £680<br />

22. Sagano Bamboo Grove.Teruhide Kato (b. 1936), c.1990. 320<br />

x 130mm. £170

Henry Sotheran Limited 11<br />

23 24<br />

25 26<br />

23. Pagoda with Full Moon.Teruhide Kato (b. 1936), c.1990. 320<br />

x 130mm. £170<br />

24. View of Bridge with Cherry Blossom, Janome, Roji.<br />

Teruhide Kato (b. 1936), c.1990. 320 x 130mm. £170<br />

25. Kurama Temple with Cherry Bloom by Moonlight.Teruhide<br />

Kato (b. 1936), c.1990. 315 x 130mm. £105<br />

26. Cherry Blossom Dance in Moonlight. Teruhide Kato (b.<br />

1936), c.1990. 130 x 320mm. £170

12<br />

LAndScApES<br />

27<br />

28<br />

27. Shinobazu Pond with Torii Gate and Willow. Shiro Kasmatsu<br />

(1898-1992), c.1950. 360 x 250mm. £800<br />

28. Shuzenji Hotspring with Cherry Blossom in Spring. Shiro<br />

Kasmatsu (1898-1992), 1937. 375 x 255mm. £900

Henry Sotheran Limited 13<br />

29<br />

29. Cave Temple of Kannnon in the Iwai Valley with a Waterfall and Pine Trees. Hiroshige Ando (1797-1858), december 1853. 340<br />

x 230mm. £1,500

14<br />

LAndScApES<br />

30 31 32<br />

33 34 35<br />

30. Toshogu Shrine at Ueno with Cherry Blossom. Shiro<br />

Kasmatsu (1898-1992), 20th c. 365 x 240mm. £180<br />

31. Tree in Full Moon. Shiro Kasmatsu (1898-1992), 20th c. 365<br />

x 240mm. £180<br />

32. Hot Spring at Semi with Cherry Blossom. Shiro Kasmatsu<br />

(1898-1992), 20th c. 365 x 240mm. £180<br />

33. Moon and Pine Tree at Matsushima. Shiro Kasmatsu (1898-<br />

1992), 20th c. 365 x 240mm. £180<br />

34. Sailing Ship. Shintaro, 20th c. 360 x 235mm. £225<br />

35. Night Scene of Kitano Shrine. Takeji Asano, (1900-1999),<br />

20th c. 360 x 235mm. £225

Henry Sotheran Limited 15<br />

37<br />

36<br />

36. Hirosaki Castle in Moonlight. Shuncho Mori (active c.1940-<br />

1950), 1930. 380 x 250mm. £980<br />

37. Glittering Sea by Moonlight. Hasui Kawase (1883-<br />

1957),1926. 370 x 250mm. £1,400

16<br />

LAndScApES<br />

38 39 40<br />

41 42<br />

38. Moon Light in Yasaka Pagoda. Takeji Asano, 20th c. 360 x<br />

235mm. £225<br />

39. Pagoda in Kyoto. Toshi Yoshida, 1932, signed in pencil by the<br />

artist. 240 x 170mm. £270<br />

40. Moon Light in Wakanoura. Wakayama. Takeji Asano, 20th<br />

c. 360 x 235mm. £225<br />

41. Temple with Cherry Blossom in the Spring. Koitsu Ishiwata<br />

(1897-1987), 20th c. 360 x 240mm. £180<br />

42. Golden Pagoda with Pine Trees in the Snow. Koitsu Ishiwata<br />

(1897-1987), 20th c. 365 x 240mm. £180

Henry Sotheran Limited 17<br />

43 44<br />

45 46<br />

43. Full Moon with Pine Trees at Akashi. Koitsu Tsuchiya (1870-<br />

1949), c.1950. 360 x 240mm. £350<br />

44. Birds in the Woods.Tamami Shima (1937-1999), 1959. 380 x<br />

530mm. £250<br />

45. Rainbow and Pine Tree. Takeji Asano (1900-1999), 20th c.<br />

360 x 240mm. £180<br />

46. Zen Rock Garden. Junichiro Sekino (1914-1988), 20th c. 430<br />

x 240mm. £550

18<br />

LAndScApES<br />

48 47<br />

49<br />

47. Bamboo Tree of the Friendly Garden. Toshi Yoshida (1911-<br />

1995), 1980. 500 x 250mm. £1,500<br />

48. Pine Tree of the Friendly Garden. Toshi Yoshida (1911-1995),<br />

1980. 500 x 250mm. £1,500<br />

49. Plum Tree of the Friendly Garden.Toshi Yoshida (1911-<br />

1995), 1980. 500 x 250mm. £1,500<br />

£4,200 for the set of three

Henry Sotheran Limited 19<br />

50 51<br />

52<br />

53<br />

50. Gion in Kyoto. Kiyoshi Saito. numbered 59/100, signed by<br />

the artist in pencil, Japan, 1963. 385 x 525mm. £1,950<br />

51. Pagoda in Snow. Junichiro Sekino (1914-1998), 20th c. 300 x<br />

450mm. £550<br />

52. Boat at Night. Anonymous, 19th c. 83 x 250mm. £75<br />

53. Autumn Sunshine Afternoon. Miyamoto Shufu (b. 1950),<br />

1992. 300 x 450mm. £480

20<br />

KIMOnOS<br />

Anonymous. Original woodblock prints, from Seasonal Kimono Design, published by Yamada Unsodo, Japan,<br />

c.1890. 160 x 110mm each.<br />

54 55 56<br />

57 58 59<br />

60 61 62<br />

54. Plum Blossoms Floating. £75<br />

55. Flower by Stream. £75<br />

56. Bamboo in Snow. £75<br />

57. Water Mill Under Pine Tree. £70<br />

58. Cherry Blossom Through the Clouds. £70<br />

59. Pine, Bamboo and Plum Blossoms. £70<br />

60. Wysteria Flower by the Gate. £70<br />

61. Plover Bird above the Ocean. £70<br />

62. Plum Blossom and Bamboo. £70

Henry Sotheran Limited 21<br />

63 64 65<br />

66 67 68<br />

69 70 71<br />

63. Shishi Lion Dance. £45<br />

64. Bridge Under the Clouds. £70<br />

65. Chrysanthemum Flower Arrangement. £45<br />

66. Morning Glory Flowers. £65<br />

67. Balloon Flower and Pampas Grass. £65<br />

68. Plum Blossom Tree. £65<br />

69. Boat and Bamboo. £65<br />

70. Boats Made of Leaves and Paper. £65<br />

71. Plum Blossom. £55

22<br />

KIMOnOS<br />

72 73 74<br />

75 76 77<br />

78 79 80<br />

72. Gentleman’s Kimono. £55<br />

73. Fishing Net and Bamboo Leaves. £55<br />

74. Maple Leaf and Floating Log. £55<br />

75. Wisteria Flower and Wave. £55<br />

76. Iris Flower Garden. £55<br />

77. Paulownia Flower and Bamboo. £55<br />

78. Narcissus Flower. £55<br />

79. Morning Glory Flowers. £50<br />

80. Boat and Bamboo. £50

Henry Sotheran Limited 23<br />

81 82 83<br />

84 85 86<br />

87 88 89<br />

81. Cherry Blossom. £50<br />

82. Kimono Fabric with Bamboo in The Wind. £40<br />

83. River. £50<br />

84. Fan Over The Water. £50<br />

85. Wishing Board with Cloud Design. £45<br />

86. <strong>Japanese</strong> Bush Clover, Bamboo and Water Pipe. £45<br />

87. Kites in the Wind. £45<br />

88. Village in the Rain, with Bamboo. £45<br />

89. Feather Fan and Tree. £45

24<br />

KIMOnOS<br />

90 91 92<br />

93 94 95<br />

96 97 98<br />

90. Hagoita Racke, with Bamboo. £45<br />

91. Gentleman’s Hats. £45<br />

92. Plum Blossom on the Verandah. £45<br />

93. Pine Tree and Wisteria Flowers above the Waves. £45<br />

94. Plover Bird and Cloud Pattern. £45<br />

95. Plant Arrangements. £45<br />

96. Bobbin Pattern. £45<br />

97. Sparrow and Rice Plant. £45<br />

98. Bridge Seen Through Clouds. £45

Henry Sotheran Limited 25<br />

99 100 101<br />

102 103 104<br />

99. Shinto Decoration with Bamboo. £45<br />

100. Treasure Boats of Good Fortune, with Rice and Bamboo. £45<br />

101. Plum Blossom, Bamboo and Pine Needles. £70<br />

102. Decorative Mirrors with Good Luck Symbols of Bamboo,<br />

Crane, Pine, Cherry Blossom and Paulowina. £55<br />

103. Decorative Curtain with Butterfly Motif. £65<br />

104. Kimono Design of Famous Poets. Yamashita Kosen, from The<br />

Hanakata series, by Miyata Toyamado, 1900. 155 x 220mm. £305

26<br />

fLOWErS<br />

105<br />

106<br />

107<br />

105. Plum Blossoms. Jakuchu (1716-1800), 20th c. 240 x<br />

240mm. £160<br />

106. Iris. Jakuchu (1716-1800), 20th c. 240 x 240mm. £160<br />

107. Plum Blossom. Jakuchu (1716-1800), 20th c. 240 x<br />

240mm. £160

Henry Sotheran Limited 27<br />

108 109<br />

110 111<br />

108. Full Moon and Cherry Blossom. nakamura Shundei (1905-<br />

1966), c.1950. 360 x 240mm. £350<br />

109. Peony Flowers and Butterfly. Kyozo, c.1920-1930. 280 x<br />

410mm. £290<br />

110. Glory Flower. nakamura Shundei (1905-1966), c.1950. 360<br />

x 240mm. £280<br />

111. Summer Fans. Kamisaka Sekka (1866-1942), 1899. 355 x<br />

240mm. £230

28<br />

fLOWErS<br />

112<br />

113<br />

114<br />

115<br />

112. Hydrangea Flower. Gakusui, 20th c. 240 x 360mm. £380<br />

113. Iris. Toyokazu Kohno (b. 1914), 20th c. 375 x 460mm. £650<br />

114. Basket with Peony Flowers. Kamisaka Sekka (1866-1942),<br />

1899. 240 x 355mm. £205<br />

115. Iris Garden. After Korin (1658-1716), 20th c. 232 x<br />

175mm. £250

Henry Sotheran Limited 29<br />

BEAUTIES And WArrIOrS<br />

116<br />

117<br />

116. Courtesan Hanaogi of the Ogiya. Utamaro II (c.1830),<br />

c.1831. 350 x 252mm. £1,600<br />

117. Courtesan Having her Hair Adjusted by her Attendant.<br />

Utamaro Kitagawa (1753-1806), c.1800. 378 x 246mm. £4,500

30<br />

BEAUTIES And WArrIOrS<br />

118 119 120<br />

121 122 123<br />

118. Courtesan Izumiya from Hiraizumi-ya Pleasure House in<br />

Shin-Yoshiwara District. Kunichika (1835-1900), november<br />

1865. 335 x 225mm. £230<br />

119. Courtesan Nakagawa from Nakamanjya Pleasure House<br />

in Shin-Yoshikawa District. Kunichika (1835-1900), november<br />

1865. 335 x 225mm. £230<br />

120. Courtesan Imamurasaki from Daikokuya Pleasure House<br />

in Shin-Yoshikawa District. Kunichika (1835-1900), november<br />

1865. 335 x 225mm. £230<br />

121. Courtesan in Shishi Patterned Kimon. Kunichika (1835-<br />

1900), January 1865. 335 x 225mm. £220<br />

122. Young Samurai Viewing Cherry Blossoms. Gekko (1859-<br />

1920), c.1890. 325 x 215mm. £175<br />

123. Courtesan Under Cherry Blossoms. Kunichika (1835-1900),<br />

January 1865. 335 x 225mm. £220

Henry Sotheran Limited 31<br />

124 125<br />

126 127<br />

124. Chapter 14: Maburashi the Wizard. Utagawa Kuniyoshi<br />

(1797-1861), from Ukiype comparison of the cloudy chapters of<br />

Genji, c.1845. 353 x 230mm. £415<br />

125. Daoist Priest Nyuunryu Kososho. Utagawa Kuniyoshi,<br />

(1797-1861), 1830. 360 x 255mm. £1,095<br />

126. Portrait of Sasaki Ganryu. Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861),<br />

1845-46. 356 x 240mm. £330<br />

127. Samurai on Horseback Descending Stairs among Cherry<br />

Blossom. Gekko (1859-1920), 1896. 350 x 225mm. £210

32<br />

BEAUTIES And WArrIOrS<br />

128<br />

129<br />

130<br />

131<br />

128. Kabuki Actor Nakamura Ganjiro. Kunichika (1835-1900),<br />

c.1880. 340 x 660mm. £255<br />

129. Kabuki Actor Ichikawa Yonezo and Nakamura Jusaburo<br />

Playing the Role of Hunter. Kunichika (1835-1900), c.1880. 340<br />

x 220mm (each). £200<br />

130. Imperial Beauty with Festive Ornaments. chikanobu<br />

(1838-1912), dptych, c.1890. 340 x 220mm (each). £230<br />

131. Apparition of a Dragon in Front of the Monk Nichiren.<br />

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), 1831. 230 x 345mm. £900

Henry Sotheran Limited 33<br />

132<br />

133<br />

132. Ohizamoto-Ladies in Waiting at the Reception in the<br />

Palace. chikanobu (1838-1912), triptych, March 1895. 700 x<br />

350mm. £405<br />

133. Beauty Enjoying <strong>Japanese</strong> Sweets Ohagi. chikanobu (1838-<br />

1912), triptych, October 1895. 700 x 350mm. £440

34<br />

BEAUTIES And WArrIOrS<br />

134<br />

135<br />

134. Geisha Entertaining. Toyokuni III ( 1786-1864), triptych,<br />

April 1857. 350 x 740mm. £635<br />

135. Festive Workmen.Yoshitora, c.1867. 335 x 720mm. £805

Henry Sotheran Limited 35<br />

136<br />

137<br />

136. Pleasure House in Shin Yoshiwara. Utagawa Kuniyoshi,<br />

(1797-1861), pentatyche, c.1850. 370 x 1300mm. £5,995<br />

137. Playing Football. chikanobu (1838-1912), triptych, from Men<br />

of the Chiyoda Palace, September 1897. 700 x 350mm. £750

36<br />

cHrYSAnTHEMUMS<br />

Keika Hasegawa (active 1893-1905). Original woodblock prints, from One Hundred Years of Chrysanthemums, Japan, July<br />

1893. 300 x 205mm each.<br />

138 139 140<br />

141 142 143<br />

144 145 146<br />

138. Chrysanthemum. £200<br />

139. Chrysanthemum. £120<br />

140. Chrysanthemum. £200<br />

141. Chrysanthemum. £200<br />

142. Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

143. Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

144. Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

145. Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

146. Chrysanthemum. £180

Henry Sotheran Limited 37<br />

147 148 149<br />

150 151 152<br />

153 154 155<br />

147. Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

148. Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

149. Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

150. Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

151. Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

152. Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

153. Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

154. Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

155. Chrysanthemum. £180

38<br />

cHrYSAnTHEMUMS<br />

156 157 158<br />

159 160 161<br />

162 163 164<br />

156. Chrysanthemum. £120<br />

157. Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

158. Chrysanthemum. £120<br />

159. Chrysanthemum. £160<br />

160. Chrysanthemum. £160<br />

161. Chrysanthemum. £120<br />

162. Chrysanthemum. £160<br />

163. Chrysanthemum. £140<br />

164. Chrysanthemum. £140

Henry Sotheran Limited 39<br />

165 166 167<br />

168 169 170<br />

171 172 173<br />

165. Chrysanthemum. £140<br />

166. Chrysanthemum. £140<br />

167. Chrysanthemum. £140<br />

168. Chrysanthemum. £140<br />

169. Chrysanthemum. £120<br />

170. Chrysanthemum. £120<br />

171. Chrysanthemum. £120<br />

172. Chrysanthemum. £120<br />

173. Chrysanthemum. £120

40<br />

cHrYSAnTHEMUMS<br />

174 175 176<br />

nankoku Ohsawa (b.1844). Original woodblock prints, Japan, early 20th century. 385 x 100mm each.<br />

177 178<br />

179<br />

174. Chrysanthemum. £100<br />

175. Chrysanthemum. £100<br />

176. Chrysanthemum. £120<br />

177. Vine and Blue Robin. £100<br />

178. Morning-Glory and Bee in August. £100<br />

179. Plum-Blossom and Flycatcher. £100

Henry Sotheran Limited 41<br />

Keika Hasegawa (active 1893-1905), 1893. 430 x 270mm each.<br />

180<br />

181<br />

182<br />

180. Large Chrysanthemum. £250<br />

181. Large Chrysanthemum. £180<br />

183<br />

182. Large Chrysanthemum. £200<br />

183. Large Chrysanthemum. £220

42<br />

BIrdS<br />

184<br />

186<br />

185<br />

187 188 189<br />

184. The Shrike Perched on a Tree. Hiroshige III, c.1880. 155 x<br />

220mm. £90<br />

185. White Herons in Snow. Gakusui, 20th c. 365 x 230mm. £350<br />

186. Rooster. Anonymous, c.1890. 310 x 420mm. £195<br />

187. Crane at Sunrise. After Okyo Maruyama, 20th c. 232 x<br />

175mm. £170<br />

188. Cranes by the Stream. After Ogata Korin (1658-1716), 20th<br />

c. 225 x 165mm. £225<br />

189. Cranes. Maruyama Okuyo (1733-1795), 18th century. 230 x<br />

170mm. £170

Henry Sotheran Limited 43<br />

190 191<br />

192 193<br />

190. Dipper Amongst Iris Flowers. rakuzenkyo, c. 1930-1940.<br />

335 x 480mm. £110<br />

191. Owls. Kaoru Kawano (1916-1965), 20th c. 260 x<br />

380mm. £400<br />

192. Great Tits Perched on Plum Blossom Tree. nakamura<br />

Shundei (1905-1966), c.1950. 360 x 240mm. £300<br />

193. Long-Tailed Tits on a Nandin Plant. nakamura Shundei<br />

(1905-1966), c.1950. 360 x 240mm. £300

44<br />

cATS<br />

195<br />

194<br />

196<br />

194. Cat with Ring. Seiji (Masaharu) Aoyama (1893-1969), 20th<br />

c. 390 x 270mm. £400<br />

195. Cat. Bairei, 20th c, 233 x 359mm. £150<br />

197<br />

196. Cat. Anonymous, c.1890. 255 x 345mm. £280<br />

197. Cat. Seicho Hasegawa (1916-2004), 20th c. 390 x<br />

270mm. £405

Henry Sotheran Limited 45<br />

198<br />

199<br />

200<br />

201<br />

202 203<br />

198. Cat. Sadanobu Hasegawa (b. 1914), 20th c. 190 x<br />

257mm. £175<br />

199. Sitting Cat. Shunsen natori, 20th c. 380 x 250mm. £480<br />

200. Cat. Sadanobu Hasegawa (b. 1914), 20th c. 260 x<br />

193mm. £175<br />

201. Cat. Sadanobu Hasegawa (b. 1914), 20th c. 190 x<br />

257mm. £150<br />

202. Cat. Sadanobu Hasegawa (b. 1914), 20th c. 215 x 145mm. £90<br />

203. Cat. Sadanobu Hasegawa (b. 1914), 20th c. 256 x<br />

191mm. £150

46<br />

AnIMALS<br />

204 205<br />

206<br />

207<br />

204. Horse. Koseki, 20th c. 340 x 261mm. £190<br />

205. Horse. nisaburo Ito, 20th c. 350 x 235mm. £160<br />

206. Monkey Reaching for the Moon. Gekko (1859-1920), 1910.<br />

247 x 260mm. £350<br />

207. Monkey. Anonymous, c.1890. 310 x 420mm. £230

Henry Sotheran Limited 47<br />

208 209<br />

210 211<br />

208. Portrait of Dragon. After Okyo Maruyama, 20th c. 233 x<br />

171mm. £190<br />

209. Portrait of Tiger. After Okyo Maruyama, 20th c. 235 x<br />

172mm. £150<br />

210. Horses. Anonymous, c.1890. 310 x 420mm. £175<br />

211. Dragon. Anonymous, c.1890. 310 x 420mm. £280

48<br />

AnIMALS<br />

212<br />

213 214<br />

212. Two Carp. Matsumoto choko (b. 1902), 20th c. 375 x<br />

460mm. £650<br />

213. Snake. Anonymous, c.1890. 310 x 420mm. £175<br />

214. Snake. Takeuchi Seiho (1864-1943), c.1900. 355 x<br />

485mm. £140

Henry Sotheran Limited 49<br />

Kodo Kawarazaki (active c.1830). Original woodblock prints, Japan, 1935. 252 x 58mm each.<br />

cLOUdS<br />

215 216 217<br />

218 219 220<br />

215. Cloud. £90<br />

216. Cloud. £80<br />

217. Cloud. £90<br />

218. Cloud. £90<br />

219. Cloud. £90<br />

220. Cloud. £90

50<br />

cLOUdS<br />

221 222 223 224<br />

225 226<br />

227 228 229 230 231 232<br />

221. Cloud. £50<br />

222. Cloud. £50<br />

223. Cloud. £50<br />

224. Cloud. £50<br />

225. Cloud. £50<br />

226. Cloud. £60<br />

227. Cloud. £60<br />

228. Cloud. £60<br />

229. Cloud. £60<br />

230. Cloud. £70<br />

231. Cloud. £70<br />

232. Cloud. £70

Henry Sotheran Limited 51<br />

233 234 235 236 237 238<br />

239 240 241 242 243 244<br />

233. Cloud. £70<br />

234. Cloud. £70<br />

235. Cloud. £70<br />

236. Cloud. £70<br />

237. Cloud. £70<br />

238. Cloud. £70<br />

239. Cloud. £70<br />

240. Cloud. £70<br />

241. Cloud. £90<br />

242. Cloud. £80<br />

243. Cloud. £80<br />

244. Cloud. £90

52<br />

MAnGA ILLUSTrATIOnS<br />

Original manga illustrations, 1986-1998.<br />

245<br />

246<br />

245. Dragon. 225 x 350mm. £300 246. Dragon Ball Z. By clamp. 200 x 350mm. £800

Henry Sotheran Limited 53<br />

247<br />

247. Eating Tiger. 215 x 230mm. £200 248. Card Captor Sakura. By clamp. 200 x 260 mm. £350<br />

248

54<br />

ScrOLLS<br />

249 250<br />

249. Koi Carp. fukuda Heihachirou. Original hand-painted<br />

design, on silk, 20th c. Image: 1060 x 410mm.; overall 1810 x<br />

527mm. £600<br />

250. Rising Dragon. nakazumi douun. Original pen and ink<br />

drawing, c.1950. Image: 1270 x 300mm; overall: 1740 x<br />

405mm. £300

Henry Sotheran Limited 55<br />

251 252<br />

251. Blossoms of the Night Moon. Yamamoto ryudou. Original<br />

pen and ink drawing, Japan, 20th c. Image: 1203 x 360mm; overall:<br />

1910 x 488mm. £700<br />

252. Blue Tit on Maple Tree. Ogata Yousui. Original pen and<br />

ink drawing, 20th c. Image: 1090 x 418mm; overall: 1830 x<br />

545mm. £700

56<br />

BAIrEI'S FlOWerS AND BirDS<br />

Original woodblock prints, from Album of Flowers and Birds, published by Okura, Japan, 1899. 335 x 215mm each.<br />

253 254 255<br />

256 257 258<br />

253. Hill Myna Birds and Roses. £200<br />

254. Azure-Winged Magpie on Akebi Tree. £200<br />

255. Plovers and Lillies. £225<br />

256. Woodpecker on a Cherry Blossom Tree. £250<br />

257. Shrike on a Plum Blossom Tree. £200<br />

258. Pheasants and a Blossoming Peach Tree. £225

Henry Sotheran Limited 57<br />

259 260 261<br />

262 263 264<br />

259. Peacocks on a Flowering Crab Apple Tree. £275<br />

260. Cherry Blossoms and Seagulls. £200<br />

261. Cormorant and Flowers by River. £225<br />

262. Herons and Iris flowers. £225<br />

263. Ducks and Lily Flowers. £225<br />

264. Blackbirds and Lily Flowers. £200

58<br />

BAIrEI'S FlOWerS AND BirDS<br />

265 266 267<br />

268 269 270<br />

265. Ducks and Peony Flowers. £200<br />

266. Waxwing on a Pear Tree. £200<br />

267. Cocks and Hydrangea Flowers. £225<br />

268. Pheasants and Peony Flowers. £200<br />

269. Grosbeak and Passion Flowers. £225<br />

270. Cranes and Peony Flowers. £200

Henry Sotheran Limited 59<br />

271 272 273<br />

274 275 276<br />

271. Pigeon on Wisteria Branches. £250<br />

272. Rooster, Hen and Chrysanthemum Flowers. £225<br />

273. Quail and Azalea Flowers. £200<br />

274. Water Rails and Camelia Sasanqua in the Full Moon. £225<br />

275. Cuckoo and Camellia Flowers. £225<br />

276. Poppy Flower and Pigeons. £200

60<br />

rELATEd BOOKS<br />

278<br />

277<br />

277. [JAPANESE ENAMELS]. BOWES, James. <strong>Japanese</strong><br />

Enamels With Illustrations from The Examples In The Bowes<br />

collection. liverpool, Printed for Private Circulation, 1884.<br />

together with notes On Shippo. A Sequel To <strong>Japanese</strong> Enamels.<br />

Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. limited, 1895. £265<br />

Small folios (280 x 194 mm.)The first work bound in the original<br />

full dark blue gilt-lettered bevelled cloth, endpapers sympathetically<br />

renewed, top edges gilt; x + [2], contents + 111 + [1]pp., advert, 20<br />

plates of which 18 are either after drawings or photos and 2 are<br />

chromolithograph plates, including frontis; a bright, clean copy. The<br />

second work bound in quarter green linen over decorative papercovered<br />

boards, top edges gilt; xii + 109 + [1]pp., 7 b/w plates and<br />

numerous b/w text figures; a little worn at the extremities otherwise<br />

a bright clean copy.<br />

first editions.<br />

278. BUXTON, L. H. Dudley. The Eastern road. london:<br />

Kegan Paul, 1924. £75<br />

8vo. Original cloth, gilt; pp. xii, 268; frontis., 18 photo. illusts.;<br />

slight spotting, else very good.<br />

first edition. This is a narrative of a journey taken in 1922 while<br />

travelling on the Albert Kahn fellowship. Although the award<br />

required Buxton to voyage throughout the world, Buxton dedicated<br />

his travels exclusively to Japan and china. china was then in<br />

turmoil, and Buxton records his impressions both at this time and<br />

in the aftermath.

Henry Sotheran Limited 61<br />

279. DENTSU INC. 100 Seasonal paintings of Japan. Japan.<br />

Dentsu inc. 1991. £98<br />

folio, original green silk lettered in gilt on spine with paper label<br />

on upper board. 100 colour illustrations. Text in <strong>Japanese</strong> and<br />

English. A fine copy in original slipcase.<br />

first edition. printed to celebrate the 90th anniversary of the<br />

founding of dentsu Inc, publishers of calenders depicting<br />

reproductions of famous works of art. A lavish promotional volume<br />

with many folding plates.<br />

280. EVANS, Robley D. An Admiral’s Log. Being<br />

continued recollections of naval Life. New York and london:<br />

D. Appleton and Company, 1910. £45<br />

8vo. Original cloth, gilt, coat of arms in gilt and silver to upper<br />

cover; pp. xi, 467; photo. illusts.; cloth slightly marked on upper<br />

cover, a little dusty, else very good.<br />

first edition. The author had previously written a volume of<br />

autobiography entitled A Sailor’s log, to which the present volume<br />

is a sequel. Evans’ service included audiences with the Emperor of<br />

Japan and the Empress dowager of china, when he was stationed<br />

in china. There are several chapters on Evans’ time in Asia<br />

(including a voyage up the Yangtze, and a visit to the philippines),<br />

as well as on the West Indies and South America.<br />

281. GILL, Stephen. European Eyes on Japan. Japan Today<br />

vol. 9. Tokyo, eU-Japan Fest Japan Committee, 2007. £28<br />

Small 4to. Three vols. Original stiff card wrappers, presented in a<br />

card slipcase, fine.<br />

first edition. photograph essays by cuny Janssen, Stephen Gill and<br />

nicu Ilfoveanu, taken between October 2006 and March 2007.<br />

commenced in 1999 the project “European Eyes on Japan” takes<br />

as its theme “contemporary people and the way they live”. Each<br />

volume is devoted to a different city or prefecture from the<br />

viewpoint of a European photographer or photographers - the focus<br />

of the present volume is Kagoshima<br />

281<br />

279 280

62<br />

282<br />

282. HILLIER, Jack. The Art of the <strong>Japanese</strong> Book.<br />

Sotheby’s. 1987. £498<br />

folio 2 volumes in original cloth with dust wrappers, preserved in<br />

original slipcase. Illustrated with reproductions of over 900 prints.<br />

A fine set.<br />

first edition of Hillier’s magnum opus, the definitive work on the<br />

<strong>Japanese</strong> Book. This copy inscribed by Hillier to his son “for Bevis<br />

from his fond father. not the least of his benefactions”.<br />

283. HOMMA, Takashi. Tokyo. New York, Aperture, 2008. £30<br />

royal 8vo. (253 x 180 mm) photo-illustrated stiff card wrappers<br />

with flaps; 239, [1]pp., illustrated throughout with colour photos;<br />

fine.<br />

first edition.<br />

283<br />

284<br />

284. [JAPAN.] A <strong>Japanese</strong> Lacquer photograph Album. c.<br />

1890. £1,750<br />

Oblong folio (approx. 14 x 10?”). Original lacquered boards, upper<br />

cover with image in gilt, colour and ivory onlays showing boatman<br />

ferrying a woman across a river, original morocco spine, gilt-ruled<br />

raised bands, a.e.g; containing 50 photographs, each approx. 206 x<br />

265, the majority coloured, captioned in English and numbered in<br />

the negative; very slightly rubbed, one small chip to edge of upper<br />

board, some tissue-guards torn, else a splendidly preserved example<br />

of the genre, contained in a purpose-made cloth box (worn).<br />

This wonderful album and others like it were produced in Japan as<br />

souvenirs, the photographs being selected from the studio catalogue<br />

purposely for the album. The present excellent copy contains images<br />

of scenes at Yokohama (the railway station and a boys’ parade),<br />

Asakusa Tokyo, cherry blossom, iris gardens and maple trees in<br />

Tokyo, Enishima, temples at nikko and the Inland Sea, views at<br />

Hakone, another of Mount fuji, portraits of geishas, silk-weavers,<br />

rice-planting, a grocer’s shop, a street-dancer, and a group portrait<br />

of soldiers dressed in Samurai armour.

Henry Sotheran Limited 63<br />

285. [JAPAN - PAPERMAKING]. [Tokyo celluloyd<br />

company Memorial Album]. [Tokyo, Taisho 8 i.e. 1919]. £148<br />

Oblong 8vo. Original decorated cloth, ties; pp. [ii, text in <strong>Japanese</strong>]<br />

+ 28 photographic plates + [iv, <strong>Japanese</strong>] text; some wear and<br />

soiling to cloth, internally very clean.<br />

An interesting photographic record of a paper-manufacturer<br />

established in Tokyo in 1917. Included are images of the<br />

laboratories, manufacturing facilities, dining hall and various<br />

company premises, as well as portraits of the company president<br />

and employees. The text and photograph captions are in <strong>Japanese</strong>.<br />

Industrial production of paper began in Kobe in 1872 and in the<br />

early c.20th demand for paper rose dramatically.<br />

285<br />

286. JAPAN. palaces Of Japan. Tokyo, 1928. £1,250<br />

Oblong folio (267 x 372 mm), bound in jade green silk, with paper<br />

title label to the upper cover, gilt-flecked endpapers, preserved<br />

within the original hand-stencilled linen-backed chemise with ivory<br />

tags and a paper title label to its upper cover; 76 phototypes, frenchfolded,<br />

each with a leaf of descriptive text (<strong>Japanese</strong>); wear to the<br />

extremities of the chemise, a few dust marks on the covers, the book<br />

itself very bright and clean.<br />

A visual survey of the imperial palaces and offical residences in and<br />

around Tokyo. The images include many interiors and gardens.<br />

286

64<br />

287<br />

287. [JAPANESE PEONY CATALOGUE]. [Yokohama<br />

Ueki Kabushiki Kaisha]. paeonia Moutan, a collection of<br />

50 choice Varieties. Yokohama. [ca. 1900]. £4,000<br />

Oblong folio, 300 x 410 mm. original blue <strong>Japanese</strong> ripple-grained<br />

paper wrappers with lithographed paper label on upper cover, stabstitched<br />

with yarn ties; 25 full-page chromolithographs, printed on<br />

rectos and versos of 13 leaves, copyright leaf at end; fine.<br />

A fine copy of one of the special nursery sample catalogues issued<br />

by the Yokohama nursery company, a consortium of <strong>Japanese</strong><br />

nursery owners who dominated the lucrative market of flower<br />

export at the height of the Western vogue for <strong>Japanese</strong> gardens.<br />

Earlier catalogues from the nursery (notably their Maple<br />

catalogues) used pochoir (stencil-coloured) illustrations; the present<br />

catalogue, showing the stunningly bright blossoms of various<br />

different species of peonies, makes effective use of the full range<br />

of tones offered by chromolithography. The flowers are shown<br />

close up, most life-size or larger, against a background of green<br />

leaves and pale green sky; the effect is extraordinarily dreamlike.<br />

Two varieties are shown in each lithograph; each has a small<br />

rectangular caption with the catalogue number in Arabic numerals,<br />

and the name of the flower in <strong>Japanese</strong> with English transcription<br />

or Latin name. The copyright or colophon leaf at end, entirely in<br />

<strong>Japanese</strong> except for the words “copyright reserved,” may supply the<br />

date.<br />

The nursery issued catalogs until about 1922, which are collected<br />

as much for their aesthetic beauty as for the detailed evidence they<br />

provide of flower and exotic plant imports at the turn of the century.<br />

Individual trees (including bonsais) and shrubs from the Yokohama<br />

nursery can still be found in the Arnold Arboretum and the<br />

Brooklyn Botanic Garden, and among the cherry tree plantings in<br />

Washington, d.c. This is a spectacular example of one of the rarer<br />

flower catalogues issued by the nursery. Two small abrasions to<br />

lithograph no. 35-36, tiny marginal tears to lower edge of first plate;<br />

corners a trifle bumped, some fading to covers, else a fine, bright<br />

copy.<br />

Five copies are listed in rliN and OClC, of which four in America.<br />

288. [JAPAN AND CHINA]. KNOX, Thomas W.<br />

(author). Adventures of Two Youths in a Journey To Japan<br />

And china. The Boy Travellers in the far East. New York;<br />

Harper & Brothers, Publishers. 1880 [1879]. £128<br />

Large 8vo. Original rich red cloth very strikingly decorated in black,<br />

gilt, and silver to both covers and spine, pictorial green endpapers,<br />

plain edges; pp. [ix], 10-421 + [ii]; with coloured frontispiece<br />

guarded by tissue and a host of fine steel-engraved illustrations<br />

printed as full-page plates and vignettes on almost every page;<br />

externally a near fine, and beautiful, copy exhibiting none of the<br />

usual fading to cloth, just one minute (2mm) closed split at base of<br />

spine; internally also very clean and crisp with cracking to endpaper<br />

at inner upper hinge and previous owner’s de luxe (donald S.<br />

Stralem), and small, leather booklabel to front pastedown, otherwise<br />

immaculate.

Henry Sotheran Limited 65<br />

290<br />

288<br />

289<br />

first edition. A highly detailed, and diverse, account of the author’s<br />

travels across the far East planted in a fictional context, but firmly<br />

rooted in fact. The work includes a 16-page account of a whaling<br />

voyage, along with descriptions of many major cities, famous<br />

natural and man-made features such as Mount fuji and the Great<br />

Wall, and observations on all aspects of local life including religion,<br />

traditions, amusements, clothing, childish pastimes, rural life, the<br />

role of women, modes of torture, manufacture, tea-drinking and<br />

kite-flying, to name but a few.<br />

289. [LEACH, Bernard]. Yanagi SOETSU. (editor).<br />

Kogei. no. 53. May 1935. Tokyo, Nippon Mingei Kyokwai, May,<br />

1935. £425<br />

8vo. (224 x 152 mm.). Original plaid cloth covered wrappers; [iv]<br />

+ 41 + [1] + [68]pp. + 10 leaves, each with a photo plate mounted<br />

at large, of which 5 are coloured + [4]pp.; text in English and<br />

<strong>Japanese</strong>; a particularly fine copy of a scarce title.<br />

Edited by Yanagi Soetsu the founder of the Mingei (folk craft)<br />

Movement in the 1920s, this issue of Kogei contains three essays<br />

by his life-long collaborator, Bernard Leach, just prior to his return<br />

to England after fourteen years living and working in Japan.<br />

The concern of Soetsu was to draw attention to the high quality and<br />

beauty of artisan crafts, including pottery, being subsumed by<br />

growing urbanisation and mass-production.<br />

290. MILLER, Dorothy C. and William S.<br />

LIEBERMANN. The new <strong>Japanese</strong> painting and Sculpture.<br />

New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 1966. £45<br />

Square 4to. Original red cloth, the title stamed in white to the upper<br />

board and spine, photographic dustjacket; 116pp., illustrated<br />

throughout with b/w photo plates; a particularly fine copy in a fine<br />

dust jacket.<br />

first edition.<br />

291. ONAKA, Koji. Slow Boat. Cologne, Schaden, 2008.£55<br />

Small 4to (233 x 265 mm). White paper covered boards, photoillustrated<br />

dust jacket; 84 b/w photographs.<br />

first German edition. Initially published in Japan in 2003.<br />

291

66<br />

THE rArE fIrST LATIn EdITIOn Of AccOUnTS Of<br />

JApAn And cHInA BY rOdrIGUES And rIccI<br />

292<br />

292. RODRIGUES, João and Matteo RICCI. Litterae<br />

Japonicae anni M. dc. VI. chinenses anni M. dc. VI. & M.<br />

dc. VII. Illae à r. p. Ioanne rodriguez, hae à r. p. Matthaeo<br />

ricci... transmissae ad admodum r. p. claudium<br />

Aquavivam... Latinè redditae à rhetoribus collegii Soc. Iesu<br />

Antuerpie. Antwerp: Officina Plantiniana, the widow and sons of<br />

Jan Moretus i [i.e. Martina, née Plantin and Balthasar i and Jan<br />

ii], 1611. £6,950<br />

12mo. contemporary netherlandish vellum over boards [?for the<br />

publisher], yapp fore-edges, alum-tawed pigskin fore-edge ties,<br />

spine lettered in manuscript by an early hand and further titled by a<br />

[?]19th-century hand; pp. 201, [1 (privilege)], [2 (plantin device,<br />

verso blank)], woodcut device on title, woodcut head- and tailpieces<br />

and initials; covers slightly warped and discolored, ties slightly<br />

rubbed and discolored, one missing a small section, light browning,<br />

a few spots, small paper-flaw on A2 affecting one letter, nonetheless<br />

a very fresh copy in a contemporary binding, retaining the final<br />

leaf with the plantin device; provenance: the Plantin-Moretus<br />

family (vide infra).<br />

First Latin edition of two important Jesuit letters to the General of<br />

the Society of Jesus, claudio Acquaviva (1543-1615, generally<br />

considered the most effective administrator of the Society since St<br />

Ignatius Loyola, and the creator of the ‘ratio Studiorum’). The<br />

translations were undertaken at the Jesuit college in Antwerp under<br />

the direction of Herman Hugo (1588-1629), and the various<br />

translators of different passages are credited in shoulder- or sidenotes<br />

besides the text. The work contains an introduction by Jacob<br />

de cater (1593-1657), and the two letters are prefaced by laudatory<br />

poems, respectively on the undertakings of the Jesuit missionaries<br />

in Japan — ‘r[everen]dis patribus Societatis Iesu in Iaponia pro<br />

fide laborantibus plausus’ by de cater (p. 8) — and on the Jesuit<br />

missionaries in china by Jean Gaspard Gevaerts (1593-1666):<br />

‘r[everen]dis patribus Societatis Iesu in china agentibus gratulatio’<br />

(p. 129).<br />

Although the first letter is often thought to be by the portuguese<br />

Jesuit João rodrigues Girão (1558-1629), the provincial of Japan<br />

and author of a number of letters from Japan in the first quarter of<br />

the seventeenth century, d.f. Lach and E.J. van Kley state that it<br />

was ‘apparently’ written by the portuguese Jesuit João rodrigues,<br />

‘The Interpreter’ (?1561-1633), the procurator of the Jesuit mission<br />

in Japan (Asia in the Making of europe (chicago and London: 1965-<br />

1993), III, p. 370); certainly, the evidence of the title-page seems to<br />

support this, since the provincial’s name usually appeared in its full<br />

form (rather than as here). João rodrigues was born in Sernancelhe<br />

in northern portugal (ironically also the origin of the Marquis de<br />

pombal’s family) and sailed from Lisbon for nagasaki in about<br />

1575, arriving in Japan in 1577 as a teenager, where he remained<br />

(apart from a brief visit to Macao in 1596) until 1610. during this<br />

time rodrigues was based at nagasaki, where he ‘rose rapidly in<br />

power and influence because of his obviously superior command of<br />

Japan’s language and customs. As a portuguese, and one of the very<br />

few portuguese then working in the Jesuit mission of Japan,<br />

rodrigues occupied a unique position as “interpreter”. Increasingly<br />

he was called upon to act as a personal intermediary between the<br />

nagasaki Jesuits and the political authorities of Japan’ (op. cit. III,<br />

p. 170). rodrigues was also responsible for the pioneering Arte da<br />

lingoa de iapam, which was published in nagasaki in 1608, and

Henry Sotheran Limited 67<br />

was ‘one of the finest products of the Jesuits in Japan’ (r.J.<br />

Howgego encyclopaedia of exploration to 1800 (potts point, nSW:<br />

2003), p. 900); this remarkable work contains a grammar and guide<br />

to pronounciation, a treatise on <strong>Japanese</strong> literature and a guide to<br />

literary style, together with practical advice on the culture and<br />

society of Japan, and was followed by the Arte breve da lingoa<br />

iapoa (Macao: 1620). rodrigues’s letter for the year 1606 was first<br />

published in Italian in rome by Bartolomeo Zannetti in 1610, and<br />

gives an overview of events in 1606, discussing the death of<br />

Allessandro Valignano, the superior of the mission to the East, at<br />

Macao in 1606, the progress of colleges and residencies, and<br />

political matters. following the rise to power of Ieyasu, who<br />

appointed rodrigues his personal commercial agent at nagasaki in<br />

1601, the Jesuits felt that their fortunes were improving, and the<br />

number of converts appears to have increased enormously, from<br />

300,000 in 1600 to 750,000 in 1606 (cf. Lach and van Kley, III, p.<br />

172); however, 1606 saw greater restrictions on proselytising, with<br />

the warning that only <strong>Japanese</strong> of the non-noble classes could be<br />

converted, and a gradual increase of anti-christian feeling, which<br />

culminated in the ‘Great persecution’, shortly after rodrigues’s<br />

departure from Japan for china in 1610.<br />

The second letter printed here is from the celebrated Jesuit sinologist<br />

Matteo ricci (1552-1610), and was first published in Italian in<br />

rome in 1610 by Zannetti. ricci studied in rome, before travelling<br />

to Goa in 1578, where, apart from a period at cochin, he remained<br />

until he travelled to china via Macao in 1582. ricci, together with<br />

Michele de ruggieri and other missionaries, gradually penetrated<br />

further into mainland china and established residences at<br />

chaoch’ing in 1583 and Shaochow in 1589. from 1589, at the latter<br />

residence, ricci adopted the dress of an educated chinese and, due<br />

to his proficiency with Mandarin, dispensed with the services of<br />

interpreters. despite various setbacks, ricci’s knowledge of the<br />

sciences, astronomy, and geography became appreciated by the<br />

authorities, and in 1600 ricci was invited to enter peking by<br />

Emperor Wan-li. ricci arrived in the city in 1601, and a residence<br />

was established there in 1606, where ricci was based until his death<br />

in 1610. during this period he translated a number of works into<br />

chinese (including the first six books of Euclid), which both<br />

enhanced his reputation in cultivated chinese circles and served to<br />

propagate christian theology; however, his reputation stems<br />

principally from his letters and his journal, which was posthumously<br />

published under the title De christiana expeditione apud Sinas<br />

(Augsburg: 1615), edited by the Jesuit nicolas Trigault, who<br />

brought the manuscript back from china to Europe. This work<br />

‘became the most influential description of china to appear during<br />

the first half of the seventeenth century [... and] provided European<br />

readers with more, better organized, and more accurate information<br />

about china than was ever before available’ (Lach and van Kley,<br />

III, pp. 512-513). ricci’s ‘Litterae chinenses’ published here follow<br />

the traditional format, and recount the mission’s activities in sections<br />

relating events at the residences of Shaochow (established in 1589),<br />

nanch’ang (1595), nanking (1599), and peking.<br />

This first Latin edition of these two important accounts — in the<br />

language through which they would become best known — is<br />

rare on the market, and no other copy can be traced in ABpc<br />

since 1975. This copy is particularly remarkable for its<br />

provenance: it was previously in the collection of the plantin-<br />

Moretus family, and was retained by them as a duplicate,<br />

following the sale of the family collections and property to the<br />

city of Antwerp in 1876 by Jonker Edward Moretus; it therefore<br />

seems most probable that this is the original binding.<br />

Cordier, Japonica col. 257; Cordier, Sinica col. 806; le Pagès<br />

‘Supplément’ p. 26; Simoni, low Countries 1601-1621, r-89 (noting<br />

2 copies in the Bl, one lacking final leaf); Sommervogel i, col. 447.<br />

293<br />

293. SARGENT, W. R. The copeland collection. chinese<br />

and <strong>Japanese</strong> ceramic figures. Massachusetts: Peabody<br />

Museum of Salem, [1991]. £35<br />

4to. Original cloth in dustwrapper; pp. 287; numerous colour<br />

illustrations from photographs; as new.

68<br />

294<br />

294. [SINO-JAPANESE WAR, 1894 5.] A <strong>Japanese</strong> Meiji<br />

print of the Sino-<strong>Japanese</strong> War, 1894-5. Tokyo, 1895. £250<br />

Oban triptych coloured woodblock print (730 x 380 mm), sometime<br />

joined together, brown discolouration visible along vertical joins<br />

where glue applied, else in very good condition.<br />

A print depicting the aftermath of a land battle on the Liaodong<br />

peninsula. The victorious <strong>Japanese</strong> stand on a defensive wall,<br />

<strong>Japanese</strong> flag flying as their trumpeters herald success. It is called<br />

picture of the Second Army occupying Jinzhou castle and was<br />

issued in January Meiji year 28 (A.d. 1895) by the publishers<br />

Kichijiro Inoue who had it engraved by Watanake Yatarou, also<br />

known as Horiyata, an eminent engraver of the Meiji period. The<br />

Liaodong peninsula on which Jinzhou is located was a major battle<br />

site during the conflict. Its capture by the <strong>Japanese</strong> crippled the<br />

chinese, who after the war were forced to cede it to Japan in the<br />

Treaty of Shimonoseki (17 April 1895).<br />

“By 1894 Japan was ready to prove to the world that her recent<br />

efforts at modernization were more than skin-deep. Ironically, the<br />

best demonstration that she was a fully civilized country was to<br />

wage war. Although brief in duration, lasting less than a year from<br />

August 1894 until May 1895, the Sino-<strong>Japanese</strong> War galvanized the<br />

entire nation with patriotic fervor and a thirst for territorial<br />

expansion. It also gained her the measure of respect she sought<br />

from Western nations . “The war naturally stimulated documentary<br />

photography and gave rise to a steady stream of illustrated<br />

newspaper articles, but the woodcuts, which for the most part had<br />

only a tenuous basis in fact, provided large-scale, colourful images<br />

that must have satisfied a deep-seated aesthetic impulse at the same<br />

time that they pandered to national pride”<br />

(Meech-pekarik, World of the Meiji print p. 200, 201).<br />

295. STANTON, F.M. Album of watercolour botanical<br />

drawings. [No place, probably england] [ca. 1818-28]. £16,000<br />

folio-sized album, 439 x 355 mm, retrospective half green calf gilt<br />

and contemporary red paper boards, contemporary green calf<br />

lettering piece gilt on front cover, titled “Specimens of Oriental<br />

Tinting,” preserved in modern green cloth folding box; 20 fine<br />

paintings of flowers (ca. 380-395 x 297-315 mm), in watercolour<br />

and bodycolour, all but one with captions in gold ink, 12 signed<br />

“Tinted by f. M. Stanton” and 4 initialed “f.M.S.” Manuscript list<br />

of contents (Latin plant names) on a quarto leaf tipped in at front,<br />

listing 24 plants; the 20 present in the album checked off in later<br />

pencil; fine.<br />

A lovely nineteenth-century album of brilliant watercolour flower<br />

paintings. The flowers include roses, dahlias, peonies and above<br />

all American and other exotic species, including passion flowers,<br />

the Aztec lily (amaryllis formosissima), persian pearl tulip (“Tulipa<br />

Oculis Solis”), camellia Japonica, magnolias, dahlias, Jalap<br />

bindweed (convolvulus Jalapa), and a purple poppy.<br />

Vividly coloured, the original watercolours, presumably produced<br />

by the same artist, are applied on thick wove paper and positively<br />

glow. The stencil technique of “oriental tinting” used to produce<br />

these paintings involved transferring a drawing using tracing or<br />

“oriental” paper to surfaces such as wood, velvet, silk, marble or

Henry Sotheran Limited 69<br />

paper, and working up the colours to the desired brilliancy.<br />

In 1829, writing in his Art of drawing and colouring from nature,<br />

the drawing-master nathaniel Whittock described Oriental tinting<br />

as a method “now in general practice” and useful for “persons<br />

unacquainted with drawing.” related to the American technique of<br />

“theorem painting,” the technique produced splendid results: most<br />

satisfying to amateurs, it was largely practiced by women, during<br />

the period “when painting in watercolours was a necessary<br />

accomplishment of every young lady who aspired to elegance and<br />

taste” (Hardie, English coloured Books, p. 123).<br />

The approximate date of this unique album derives from the<br />

watermark of the manuscript list of flowers bound in at front, which<br />

is dated 1828.<br />

295

70<br />

296<br />

296. TAKAHASHI, G[oro]. Short Biographies of Emineni<br />

[sic] <strong>Japanese</strong> in Ancient and Modern Times each with a<br />

characteristic Illustration. Tokyo, Kyushundo, 1890. £2,000<br />

8vo. 2 vols. Original wrappers, string ties, printed title labels to<br />

upper wrappers; both vols. pp. [ii, English text including an<br />

“Advertisement”] + [40] + [ii, <strong>Japanese</strong> text]; both vols. 10 doublepage<br />

hand-coloured wood-engraved portraits, with ownership<br />

inscriptions to the wrappers in chinese calligraphy of chiang Yee,<br />

who wrote travel books as “The Silent Traveller”; slight soiling to<br />

wrappers, else a near-fine copy.<br />

first editions. Both volumes have the same advertisement stating<br />

that this is the second volume of a run of 10 which would<br />

complement another 10-volume series entitled “The pictorial<br />

descriptions of a Hundred famous places of Japan”. However, the<br />

text and the illustrations in each volume are different. We have been<br />

able to trace only the first volume of the “Eminent <strong>Japanese</strong>” series<br />

in other libraries (Yale and the British Library) and have been unable<br />

to tell whether the series was ever completed, which makes this set<br />

extremely unusual and interesting.<br />

The biography for each person covers 2 leaves of text before and<br />

after the illustration for that person. The illustrations themselves,<br />

each signed by the <strong>Japanese</strong> artist, offer “characteristic” portrayals<br />

by setting the person within a scene of importance in their life. The<br />

subjects in the first volume comprise The Emperor nintoku, prince<br />

Shotoku, Sugawara no Michizane, Taira no Masakado, Minamoto<br />

no Yoritomo, Madenokoji fujifusa, Aoto fujitsuna, Murasaki<br />

Shikibu, Iwakura Tomomi and Yui no Shosetsu. The second volume<br />

describes Yamatotake no Mikoto, Jingu Kogu, Takenouchi no<br />

Sukune, Wage no Kiyomaro, Minamoto no Yoshie, Taira no<br />

Shigemori, Hojo Tokimune, Kusunoki Masashige, Kato Kiyamasa<br />

and Saigo Takamori.<br />

Not found in Wenckstern’s Bibliography of the <strong>Japanese</strong> empire.<br />

297. THOMAS, Edward. Lafcadio Hearn. Constable and<br />

Company ltd. 1912. £150<br />

Small 8vo. publisher’s green cloth, gilt spine; pp. 91 + 5 [ads.],<br />

frontispiece portrait of Hearn; very bright and clean indeed.<br />

first edition, second impression. Scarce. One of many books of<br />

literary biography produced by Thomas during this period, this is<br />

nonetheless a well-researched and sensitively written account of the<br />

life and work of the journalist and short story writer. Thomas is<br />

particularly strong on Hearn’s role in introducing Western readers<br />

to <strong>Japanese</strong> culture.<br />

297

Henry Sotheran Limited 71<br />

298<br />

299<br />

298. TILLEY, Henry Arthur. Japan, the Amoor, and the<br />

pacific; with notices of other places comprised in a Voyage<br />

of circumnavigation in the Imperial russian corvette<br />

“rynda” in 1858-1860. Smith, elder and Co., 1861. £1,250<br />

8vo. Original green cloth gilt; pp. xii + 405 + 2 (ads.) + 16 (pubs.<br />

list); 8 tinted lithographs; very slightly bumped, else a near-fine<br />

copy.<br />

first edition. The Englishman Tilley served as a language tutor<br />

aboard the russian warship rynda. In September 1858 the corvette<br />

sailed as part of a small russian squadron from Brest bound for the<br />

russian Amoor. The squadron sailed round the cape to Batavia,<br />

putting in at Manila and Shanghai before a lengthy stop in Japan.<br />

Here Tilley was able to observe the recently formed russian enclave<br />

at nagasaki, as well as Yedo (Tokyo). The rynda then sailed on to<br />

the Amoor. Tilley remained there for 3 months and claimed to be<br />

the first Englishman to land there. The rynda put in subsequently<br />

at San francisco before continuing to Hawaii and Tahiti, of which<br />

Tilley gives good descriptions. The squadron finally rounded South<br />

America to reach portsmouth in May 1860. Tilley’s account<br />

provides important early documentary records of the European<br />

settlements in Japan and of the newly founded russian colony in<br />

the Amoor.<br />

Wenckstern i.105.<br />

299. WITH, Karl. Buddhistische plastik in Japan. Wein,<br />

Anton Schroll, 1919. £100<br />

4to. 2 volumes. Original decorated boards, title laid down; pp. 207,<br />

[8], containing 27 plates; 224 of additional plates.<br />

An excellent pictorial scource book of Buddhist statuary.<br />

300. YATES, Ronald E. The Kikkoman chronicles. A<br />

Global company with a <strong>Japanese</strong> Soul New York. McGraw<br />

Hill. 1998 £20<br />

8vo., original cloth with dust wrapper. A fine copy.<br />

first edition.<br />

300

72<br />

Glossary<br />

Azalea<br />

A symbol of temperance, passion and womanhood.<br />

Bamboo<br />

Growing wild throughout Japan, bamboo has long been used in a<br />

variety of ways, from food source to building material. It is an<br />

auspicious plant, and in the Orient is linked with confucian human<br />

virtues. Its evergreen leaves connote ‘constancy’, the evenly spread<br />

nodes signify ‘moderation’, and its bending in the wind implies<br />

‘moral resilience’. combined with animals it has several meanings.<br />

for example, bamboo and the sparrow together signify friendship,<br />

while the bamboo and the tiger imply safety. An image of bamboo<br />

reminds us to be resilient and to stand upright against obstacles.<br />

Bat<br />

A symbol of prosperity and happiness that was imported from<br />

china. The characters for ‘bat’ and ‘good luck’ are pronounced alike<br />

in chinese and <strong>Japanese</strong>.<br />

Boat<br />

It is said that sailing boats bring wealth from beyond the ocean. The<br />

seven lucky gods are often depicted on a treasure ship, a symbol of<br />

good fortune.<br />

Bridge<br />

Signifies a route blessed to take to salvation. A zigzag bridge<br />

prevents evil spirits from crossing, since it was believed ghosts and<br />

evil spirits could only move in straight lines.<br />

Buddha Statue<br />

represents mercy and enlightenment. Statues or images of Buddha<br />

are used as talismans against evil.<br />

Butterfly<br />

Symbolising spring, they are associated with happiness and joy.<br />

favoured for the dual nature of its delicate and elegant symmetry,<br />

and its transcendent evolution from a lowly caterpillar to noble<br />

insect, the butterfly also signifies metamorphosis or transformation.<br />

In <strong>Japanese</strong> lore souls and spirits take the shape of a butterfly,<br />

therefore they are seen as the personification of a dead or living<br />

person’s soul. Often associated with traditional Shinto weddings,<br />

two butterflies dancing about one another symbolise marital<br />

happiness.<br />

Camellia<br />

The camellia is known as the flower that brings spring. It has long<br />

been regarded as a symbol of longevity, love, happy marriage,<br />

fortune, victory and happiness.<br />

Camphor trees<br />

Often gracing Shinto shrines, their stature, compelling aroma, and<br />

long life provide an appropriate symbolic meaning of longevity and<br />

good fortune.<br />

Canna<br />

The flower of passion and respect.<br />

Carp<br />

drawing on a chinese legend of a fish so strong and persistent that<br />

it could leap a waterfall, the Koi’s determination to overcome<br />

obstacles is held to be a fitting example of ambition, strength and<br />

the will to overcome difficulties. With the power to fight its way up<br />

swift streams, it symbolises persistence, bravery and strength as well<br />

as surpassing expectations. It therefore embodies the attributes<br />

desired in boys. The boys’ festival is celebrated on the 5th day of<br />

the 5th month. Balloon carps are hoisted on a long pole set in the<br />

garden or attached to the roof of the house. Usually a carp is flown<br />

for each son. Koi swimming upstream are also interpreted as<br />

showing the philosophy of non-conformism since they do not “go<br />

with the flow”. This signifies independence of the mind. Since they<br />

can live for centuries, Koi are also a symbol of immortality.<br />

Castle<br />

The castle demonstrated the political and military strength and<br />

wealth of the samurais and feudal lords. It is now recognised as a<br />

symbol of strength.<br />

Cat<br />

Statues or images of cats are often placed in <strong>Japanese</strong> shops and<br />

businesses as a lucky charm, in the hope that the establishment will<br />

prosper. The most popular kind of lucky charm in <strong>Japanese</strong> stores<br />

is a figurine which has the shape of a cat waving its paw; the<br />

“Maneki neko”. The cat whether it keeps away pests or attracts<br />

customers, symbolises success and good fortune.

Henry Sotheran Limited 73<br />

Cherry Blossom<br />

The pride of Japan; the coronation of spring breaks out into pink<br />

clouds of blossoms that gradually spread over the land in early April.<br />

Stemming from ancient Shinto beliefs, cherry blossoms have been<br />

historically revered by the <strong>Japanese</strong>. cherry blossom or “sakura” is<br />

generally believed to be a corruption of the word “sakuya”<br />

(blooming) from the name of a mythical princess who is enshrined<br />

on the top of Mt fuji. Her name literally means “tree-flowersblooming-princess”,<br />

because she dropped from heaven onto a cherry<br />

tree. Ever since its close connection with Shinto, the cherry blossom<br />

has been considered the most spiritually pure of flowers. They<br />

transform the country into a fairyland which has given Japan its<br />

floral name of “The Land of the cherry-Blossom”. As symbols of<br />

the beauty and purity of life and of how quickly it fades away, they<br />

remind us all to live and enjoy life to the full.<br />

Chrysanthemum<br />

Is one of the four noble flowers (the others being the plum blossom,<br />

the orchid, and bamboo). The flower of autumn meditation and<br />

fullness, it symbolizes not only a long life but also a complete and<br />

content one. Since it blooms after summer, it is associated with<br />

aspects of autumn such as relaxation after the harvest season and<br />

periods of quiet contemplation. It can also symbolise sanctuary and<br />

refuge. The chrysanthemum’s link to longevity draws from its<br />

physical appearance. circular and symmetric with centric rays, it is<br />

a solar symbol associated with life, longevity and Japan itself. As a<br />

symbol of the nation, the emperor of Japan adopted it as his crest<br />

and it is depicted on the Imperial Seal.<br />

Cockerel<br />

A symbol of potency and power because of its propensity for<br />

fighting.<br />

Crane<br />

One of the three major mystical animals, together with the dragon<br />

and the tortoise. Its chief symbolic meaning is long life. With their<br />

lifespan of some thirty years, cranes were thought to live not just<br />

decades but thousands of years, becoming virtually synonymous<br />

with immortality. At <strong>Japanese</strong> weddings it is a symbol of loyalty.<br />

Also associated with the qualities of honour and wisdom, cranes<br />

were believed to be intermediaries between heaven and earth, a<br />

messenger of the gods to humans, thus symbolising the spiritual<br />

ability to enter a higher state of consciousness. furthermore, the<br />

crane also represents a lasting soaring spirit, health, and happiness.<br />

Their white bodies stand for purity and their red heads denote<br />

vitality.<br />

Crow<br />

The crow represents filial devotion and is also associated with<br />

chinese astrological and cosmic philosophy. It is said that a threelegged<br />

crow (yatagarasu) lives in the sun. In <strong>Japanese</strong> art crows are<br />

therefore depicted with the sun as a background. A white heron and<br />

a black crow are symbolic of day and night.<br />

Daffodil (Narcissus)<br />

represents respect and hospitality.<br />

Dahlia<br />

represents dignity and elegance.<br />

Dove<br />

Although the dove is a messenger of the God of war (Hachiman), it<br />

is also considered a symbol of peace as in the west. As messengers<br />

of Hachiman they were sent out primarily to avert conflict.<br />

Dragon<br />

As symbols of wisdom, strength, goodness and longevity, an<br />

impressive representation of a dragon can be of tremendous positive<br />

benefit to the owner. first in the hierarchy of mythical creatures in<br />

Japan, the dragon was one of the four animals symbolising the<br />

cardinal points associated with the east; the dragon stood for sunrise,<br />

spring and fertility. dragons were benevolent spirits associated with<br />

happiness and prosperity, and unlike European dragons, were kind<br />

to humans.<br />

Duck<br />

An auspicious symbol in <strong>Japanese</strong> literature and poetry, an image<br />

of a duck endows prints with an aura of good luck. They primarily<br />

represent happiness in marriage and fidelity.<br />

Falcon<br />

A symbol of regal power, as it became a favourite pastime of the<br />

aristocracy and samurai to hunt with falcons. It is also a symbol of<br />

keen endeavour and success, as well as boldness.<br />

Fans<br />

The fan stands for many things. The <strong>Japanese</strong> believe that the handle<br />

of the fan symbolises the beginning of life and the ribs are for the<br />

roads of life going out in all directions. It also symbolises friendship,<br />

respect and good wishes and is a gift that is given to people on<br />

special occasions.

74<br />

Fern<br />

represents long life, and happiness in marriage. Its leaves are white<br />

on one side and black on the other, which stands for honesty and<br />

sincerity.<br />

Firefly<br />

fireflies symbolise the summer and they have been a metaphor for<br />

passionate love in poetry since the 8th century. Their eerie lights are<br />

also thought to be the altered form of the souls of soldiers who have<br />

died in war.<br />

Four Noble Flowers<br />

The chrysanthemum, the plum blossom, the orchid, and bamboo.<br />

Frog<br />

The frog is thought of as good luck for travellers. Images or charms<br />

in the shape of frogs were worn during long voyages to assure<br />

safety, particularly across water. The <strong>Japanese</strong> word for frog is<br />

“kaeru”, which sounds like the word “return.” Travellers carry a<br />

small frog amulet with the intent of returning safely home.<br />

Gardenia<br />

This flower represents happiness, elegance, and sophistication.<br />

Gladioli<br />

Gladioli represent preparedness, strength, splendid beauty and love<br />

at first sight.<br />

Goose<br />

The geese on their migration journey during autumn, when the<br />

weather begins to turn cold and plants wither for the winter. This<br />

suggests the Buddhist idea that everything in life is impermanent,<br />

and that all plants and animals are born, reproduce, die, and decay.<br />

They are also a chinese emblem of caution. Wild geese normally<br />

fly in a straight line. When the line is broken it suggests that there<br />

are unusual circumstances beneath them.<br />

Heron<br />

The heron has the habit of standing perfectly still and is therefore<br />

emblematic of Buddhist meditation. Often depicted among lotus<br />

leaves, standing on one leg (it never stirs up the mud), it symbolises<br />

Buddhist purity. Associated with the black crow, it suggests day and<br />

night, good and evil.<br />

Hibiscus<br />

represents continually rejuvenating youth, beauty and bravery.<br />

Hydrangea<br />

The hydrangea is a symbol expressing love, gratitude, and enlightenment.<br />

It is said that the observer can easily get lost in its abundance of beautiful<br />

petals, and thus getting lost in higher thought and reaching enlightenment.<br />

due to its versatility, and beauty, the hydrangea makes an excellent thank<br />

you gift to an unsung hero in our lives.<br />

Iris<br />

The collection of 10th century lyrical prose and poems, Tales of ise,<br />

recounts how a heartsick lover composed poetry to a wild iris in<br />

place of his lost love. Since then the iris has come to symbolise<br />

romance and heroism. It is also a potent symbol against evil spirits.<br />

Kozuchi (miracle mallet)<br />

The Kozuchi is a legendary <strong>Japanese</strong> hammer, and translates as<br />

“Small Magic Hammer” or “Miracle Mallet”. The mallet is very<br />

small, and swinging it grants its holder’s wishes. It is a symbol of<br />

good fortune.<br />

Kuniyoshi, Utagawa (c.1797 - April 14, 1861)<br />

Together with Hokusai and Hiroshige, Utagawa Kuniyoshi is known<br />

as one of the greatest <strong>Japanese</strong> printmakers and a master of imaginative<br />

design, dominating the <strong>Japanese</strong> print world of the 19th century. The<br />

son of a silk-dyer, Kuniyoshi was initially involved in his father's<br />

business as a pattern designer, it is said that as a child he was impressed<br />

by ukiy_-e warrior print and by pictures of artisans and commoners<br />

depicted in craftsmen manuals, such as those seen in his later works.<br />

His early works include a series of prints of kabuki actors and warriors,<br />

as well as a series of pictures of beautiful women, known as bijinga,<br />

in which he experimented with large textile patterns and light-andshadow<br />

effects found in Western art. In the 1820s he was finally<br />

accepted into the important ukiy_-e circle, with his first major<br />

commission, ‘One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the popular Suikoden’<br />

based on the popular chinese tale, the Shuihu zhuan. Kuniyoshi<br />

continued to draw many of his subjects from traditional tales of war,<br />

but with an added stress on dreams, ghostly apparitions, omens and<br />

superhuman feats, themes which satisfied the public’s interest in the<br />

ghoulish, exciting and bizarre. In the 1840s Kuniyoshi’s critical view<br />

of the shogunate won him further favour with a politically dissatisfied<br />

public through a series of caricature prints in which disguised actors<br />

and courtesans were portrayed, at a time when illustrations of<br />

courtesans and actors in Ukiy_-e were officially banned. He also<br />

produced more naturalistic works of animals, birds and fish, parodies<br />

of traditional <strong>Japanese</strong> and chinese painting, and a series of landscape<br />

views incorporating Western shading, perspective and pigments. Later,<br />

he experimented radically with composition, magnifying visual<br />

elements in the image for a dramatic, exaggerated and quite modern<br />

effect, still seen today in <strong>Japanese</strong> manga illustrations. The fantastic<br />

and dynamic prints by Kuniyoshi were brought to the fore in a recent<br />

exhibition at the royal Academy and Sotheran’s is very fortunate to<br />

have several of his prints in this exhibition.

Henry Sotheran Limited 75<br />

Lantern<br />

<strong>Japanese</strong> lanterns are used to escort the bride at her wedding, and<br />

are now symbolic of good luck in marriage. They are also necessary<br />

at funeral processions where there must be two or more plain<br />

lanterns at the head, even when the funeral is held in day time, in<br />

order to lead the spirits because the land of the dead is dark and<br />

gloomy. This is why there are so many stone lanterns in shrines.<br />

Lily<br />

A lily is a plant that is used to help you forget your troubles. It is<br />

also known as the bringer of sons so is often given to a woman upon<br />

her marriage.<br />

Lotus<br />