Lessons from the land - Indigenous Flora and Fauna Association

Lessons from the land - Indigenous Flora and Fauna Association

Lessons from the land - Indigenous Flora and Fauna Association

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

March 2011 Volume 22 One<br />

A garden for learning <strong>and</strong> teaching Page 2<br />

INDIGENOTES VOLUME 22 NUMBER 1<br />

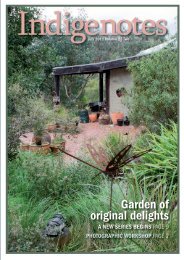

Photo: Brian Bainbridge

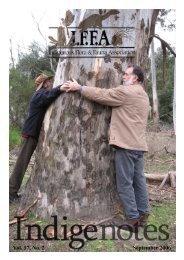

<strong>Lessons</strong> <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong><br />

Gidja Walker tends a beautiful garden that<br />

is a laboratory <strong>and</strong> classroom; a garden for<br />

learning <strong>and</strong> teaching.<br />

ON 28 February 2010, members of IFFA joined<br />

with SPIFFA (<strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Peninsula <strong>Indigenous</strong><br />

<strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Association</strong>) at <strong>the</strong> home garden<br />

of SPIFFA President Gidja Walker, who also teaches<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Conservation <strong>and</strong> L<strong>and</strong> Management Course at<br />

Chisholm TAFE.<br />

Eventually over twenty IFFA <strong>and</strong> SPIFFA members were<br />

circumnavigating Gidja’s house. This took approximately two<br />

hours as each metre held a story or lesson about <strong>the</strong> wider<br />

Peninsula environment. Over a hundred species of indigenous<br />

plants can be found <strong>the</strong>re, including remnants <strong>and</strong> cultivated<br />

plants collected <strong>from</strong> across <strong>the</strong> Peninsula. Tiny dunes <strong>and</strong><br />

wet<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s allow Gidja to grow species <strong>from</strong> a wide range of<br />

vegetation types <strong>and</strong> closely observe germination, pollination,<br />

predation <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r ecological processes.<br />

One ver<strong>and</strong>ah had pots that contained botanical refugees<br />

<strong>from</strong> coastal developments. These are providing clues on how<br />

to save <strong>the</strong>ir wild cousins in remnant bush<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>. A small looper<br />

caterpillar (family Geometridae) was eating <strong>the</strong> leaves of <strong>the</strong><br />

locally rare species of Phyllan<strong>the</strong>s which has many highly toxic<br />

relatives in <strong>the</strong> Spurge family. Instead of removing <strong>the</strong> insect,<br />

Gidja pondered whe<strong>the</strong>r it is a common species, or perhaps a<br />

specialised insect, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>refore as threatened as its food plant.<br />

Some observations were interesting but of unknown<br />

significance. We were shown how Mentha diemenica growing<br />

in <strong>the</strong> garden had white flowers, but when grown in a pot,<br />

<strong>the</strong> same plant has blue flowers. Gidja suggests this is a soil<br />

chemistry effect, like <strong>the</strong> well-known one in Hydrangea. Her<br />

observation of teeming nocturnal insect-life while driving past<br />

thickets of summer-flowering Moonah, Melaleuca lanceolata,<br />

has implications for <strong>the</strong> conservation of insectivorous bats.<br />

The problems caused by habitat fragmentation have made<br />

it crucial to identify vegetation patterns <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> processes<br />

that influence plant germination <strong>and</strong> survival. The Ecological<br />

Vegetation Classes (EVC’s) of <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Peninsula were<br />

once lumped in a basket called ‘Dune Scrub’. These have<br />

since diversified into a medley of EVC’s based on work such<br />

Gidja’s beautifully painted cross sections <strong>and</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>scapes visualise <strong>the</strong> fine<br />

structure of vegetation communities, some of <strong>the</strong>m vanished or relictual.<br />

On a tiny artifical dune grows Native Tobacco. Its presence in<br />

some areas of <strong>the</strong> peninsula suggest locations of significance<br />

for Bunurong men who used <strong>the</strong> plant <strong>and</strong> are likely to have<br />

played a role in its distribution.<br />

as Gidja’s. We were shown a patch of reddish earth where<br />

Argentine ants were bringing underlying heavier ‘terra-rossa’<br />

soils to <strong>the</strong> surface. These are a part of Gidja’s emerging picture<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Peninsula’s plant communities where Coast Banksia,<br />

Banksia integrifolia, dominated grassy wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> in low lying<br />

parts of <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>scape. The str<strong>and</strong>s of evidence used to try to<br />

reconstruct this all but vanished plant community include old<br />

place names, anomalous plant associations <strong>and</strong> observations of<br />

plant succession <strong>and</strong> revegetation performance.<br />

Beautiful watercolour diagrams support Gidja’s <strong>the</strong>oretical<br />

work. It is apparent <strong>the</strong> artistic response stimulates insights<br />

into patterns of geological <strong>and</strong> climatic influences, ecological<br />

processes <strong>and</strong> cultural practices.<br />

At nearby Rye Back beach Gidja pointed to middens<br />

<strong>and</strong> grey layers of s<strong>and</strong> marking ancient fire-pits infiltrating<br />

<strong>the</strong> dunes. Among petrified remains of stumps <strong>and</strong> trees<br />

on <strong>the</strong> beach, we were invited to tour deep time, when <strong>the</strong><br />

Peninsula’s hills overlooked grassy plains of Port Phillip Bay<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bunurong people traded with <strong>the</strong> peoples of nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Tasmania. The many links between <strong>the</strong> cultures<br />

of <strong>the</strong>se people were discussed. Again, Gidja’s<br />

experience of tending plants known to be used<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Bunurong is providing clues for <strong>the</strong>ories<br />

on Bunurong <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> management practices that<br />

may hold keys for living with <strong>and</strong> restoring <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>scapes of <strong>the</strong> present day.<br />

Almost a year later, I still rejoice at <strong>the</strong><br />

memory of a day where SPIFFA <strong>and</strong> IFFA folk<br />

came toge<strong>the</strong>r to be so generously <strong>and</strong> gently<br />

educated in Gidja’s garden.<br />

Thanks to Gidja <strong>and</strong> her family <strong>and</strong> to<br />

SPIFFA for inviting us to <strong>the</strong>ir ‘patch’.<br />

Brian Bainbridge<br />

Gidga shows how <strong>the</strong> proportions of<br />

leaves are an important feature for<br />

distinguishing <strong>the</strong> native Karkalla,<br />

Carpobrotus rossii <strong>from</strong> exotic<br />

species <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> hybrids <strong>the</strong>y form<br />

with Karkalla.<br />

Gidga fears that <strong>the</strong> South African<br />

<strong>and</strong> South American relatives of<br />

this species are causing genetic<br />

‘pollution’. An insidious effect. A<br />

taste test confirmed <strong>the</strong> luscious<br />

texture of <strong>the</strong> native species.<br />

Unfortunately, some hybrids appear<br />

to have entered <strong>the</strong> revegetation<br />

supply stream.<br />

Below: Karkalla, Carpobrotus rossii.<br />

IFFA OUTING<br />

Guided tour of Royal Botanic Garden Cranbourne<br />

Sunday 10 April 10:30 am - 1:30 pm<br />

Join Alex Smart (a member of <strong>the</strong> Friends of <strong>the</strong> RBG<br />

Cranbourne) for a special tour of <strong>the</strong> indigenous garden area<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> main constructed garden.<br />

There is a small charge to enter <strong>the</strong> main gardens.<br />

Meet at Stringybark Picnic area at 10.30 am<br />

Sunday 10 April.<br />

Please bring a picnic lunch. We hope to get to see <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Brown B<strong>and</strong>icoots, who are often visitors to <strong>the</strong> garden.<br />

Registrations essential –please contact Linda Bradburn<br />

(9416 7184 or activities@iffa.org.au).<br />

Directions to RBG Cranbourne<br />

http://www.rbg.vic.gov.au/rbg-cranbourne/directions<br />

By car. The best way to travel to Royal Botanic Gardens<br />

Cranbourne is by car or private coach.<br />

From Melbourne, drive down <strong>the</strong> Monash Freeway (M1) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n<br />

turn off at <strong>the</strong> South Gipps<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> Freeway (M420). Signs will be<br />

for Cranbourne <strong>and</strong> Phillip Is<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>.<br />

The next turn-off with signs to Cranbourne <strong>and</strong> Phillip Is<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong><br />

takes you onto <strong>the</strong> South Gipps<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> Highway (still <strong>the</strong> M420).<br />

Take this exit <strong>and</strong> follow <strong>the</strong> South Gipps<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> Highway, through<br />

<strong>the</strong> town of Cranbourne.<br />

On <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn side you will see signs pointing to <strong>the</strong> turn-off<br />

for <strong>the</strong> Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Australian<br />

Garden. The turn-off is located approximately 500 m past <strong>the</strong><br />

Cranbourne Racecourse.<br />

This trip will take approximately 50 minutes <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> Melbourne<br />

CBD.<br />

Access address<br />

Cnr Ballarto Road <strong>and</strong> Botanic Drive Cranbourne<br />

(off South Gipps<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> Highway)<br />

Melway Ref: 133 K10<br />

2 INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC INDIGENOTES VOLUME 22 NUMBER 1<br />

3

Book Review. What’s ‘Natural’? SPIFFA 20 years on . . .<br />

The Victorian Bush<br />

Its ‘original <strong>and</strong> natural’ condition<br />

By Ron Hateley<br />

Polybractea Press, South Melbourne 2010<br />

209 pp softback<br />

This book is a caution for those trying to make<br />

decisions on native vegetation management or<br />

restoration based on concepts of what <strong>the</strong> ‘original<br />

<strong>and</strong> natural’ state of <strong>the</strong> vegetation was. The earliest<br />

accounts <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> historical records are brought toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

to argue that many assumptions of forest managers <strong>and</strong><br />

ecological restorationists may be false.<br />

Hately is a Forestry lecturer, who has taken a<br />

sabbatical to investgate his nagging doubts about some<br />

of his teachings. Primary targets of <strong>the</strong> book are <strong>the</strong><br />

assumptions that prior to settlement, forests were in some<br />

kind of pristine state, <strong>and</strong> that Aboriginal burning practices in<br />

forests (as opposed to wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s or grass<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s) reduced fuel<br />

loads <strong>and</strong> kept <strong>the</strong>m open <strong>and</strong> ‘park like’.<br />

Through quotes <strong>from</strong> early settlers <strong>and</strong> explorers Hateley<br />

demonstrates that Victoria’s native vegetation was in a state<br />

of flux, that forests were subject to disturbance <strong>from</strong> extreme<br />

wea<strong>the</strong>r events (including tornadoes, extreme snowfalls, hail<br />

<strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r storm damage) occasional fires probably caused by<br />

lightning, <strong>and</strong> at least in parts supported extensive populations<br />

of parasitic plants like dodder laurels <strong>and</strong> mistletoe. In many<br />

areas <strong>the</strong> forest floor was littered with dead wood <strong>and</strong> densely<br />

shrubby.<br />

Unfortunately for a book discussing Aboriginal burning<br />

practices, it seems <strong>the</strong>re was no consultation with local<br />

indigenous communities to find out what <strong>the</strong>y knew about<br />

<strong>the</strong>se issues, <strong>and</strong> so <strong>the</strong> evidence is entirely based on European<br />

settlers accounts.<br />

“I conclude that [<strong>the</strong> burning practices of]<br />

Victorian Aboriginals did not have such a<br />

major effect on our forests, compared with<br />

<strong>the</strong> plains <strong>and</strong> wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s . . . <strong>the</strong> mountain<br />

forests of Victoria seem to me to have mainly<br />

been shaped by drought, fires caused by<br />

lighting, winds, hailstorms, snowstorms . . .<br />

<strong>and</strong> by medium term climatic cycles.”<br />

The historical accounts Hately quotes do seem to indicate<br />

that forests were infrequently used by <strong>the</strong> Aboriginal people,<br />

<strong>and</strong> that Aboriginal burning practices should not be used<br />

to justify fuel reduction burning of forests. Accounts of<br />

Aboriginal burning in forests all end up reling on interstate,<br />

mostly nor<strong>the</strong>rn Australian accounts, whereas Victorian<br />

accounts suggest little evidence of regular <strong>and</strong> widespread<br />

Aboriginal burning in forests.<br />

A strong <strong>the</strong>me emerging <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> accounts of Aboriginal<br />

burning is how <strong>the</strong>y used fire to harass <strong>and</strong> discourage<br />

explorers <strong>and</strong> early settlers. Also signal fires were lit to<br />

communicate<br />

over long<br />

distances <strong>the</strong><br />

presence of<br />

<strong>the</strong> foreigners.<br />

Early accounts<br />

of Aboriginal fire<br />

need <strong>the</strong>refore to<br />

be interpreted very<br />

carefully because <strong>the</strong><br />

observers were probably<br />

reporting higher than<br />

normal fire frequencies.<br />

Hately does not doubt<br />

that fire was used by<br />

<strong>the</strong> indigenous people to<br />

manage smaller areas of<br />

wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>and</strong> grass<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>.<br />

Early destruction of pests (top predators such as dingoes,<br />

eagles <strong>and</strong> quolls as well as wombats) <strong>and</strong> many o<strong>the</strong>r species<br />

for food, skins or <strong>the</strong> ‘joy’ of hunting mean that unpredictable<br />

changes to vegetation may have resulted. Hately argues that<br />

some of <strong>the</strong>se changes may have been mistaken for changes as<br />

a result of changed fire regimes.<br />

The bulk of <strong>the</strong> book is comprised of quotes with<br />

some narrative to tie <strong>the</strong>m toge<strong>the</strong>r. The conclusions are<br />

understated — one of <strong>the</strong> book’s main conclusions is made<br />

in one paragraph: “I conclude that Victorian Aboriginals did<br />

not have such a major effect on our forests, compared with<br />

<strong>the</strong> plains <strong>and</strong> wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s, which undoubtedly bore deeply<br />

numerous signs of <strong>the</strong>ir traditions, hunting <strong>and</strong> ga<strong>the</strong>ring,<br />

arts <strong>and</strong> craft <strong>and</strong> general <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> management. In contrast <strong>the</strong><br />

mountain forests of Victoria seem to me to have mainly been<br />

shaped by drought, fires caused by lighting, winds, hailstorms,<br />

snowstorms — in o<strong>the</strong>r words extreme wea<strong>the</strong>r events -— <strong>and</strong><br />

by medium term climatic cycles.”<br />

These are important conclusions. More<br />

discussion on <strong>the</strong> implications of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

conclusions would have been welcome.<br />

Hateley also brings toge<strong>the</strong>r quotes<br />

which demonstrate how early in <strong>the</strong><br />

settlement process selective changes to<br />

<strong>the</strong> vegetation were made — intensive<br />

harvesting of Black Wattle <strong>and</strong> Golden<br />

Wattle for tan bark — <strong>and</strong> conversely <strong>the</strong><br />

direct seeding of <strong>the</strong>se species into rail<br />

reserves <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r public <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>. Drooping<br />

Sheoke was targeted in <strong>the</strong> first years of<br />

settlement as it made excellent shingles,<br />

firewood <strong>and</strong> drought fodder. These species<br />

were manipulated so early that it is quite possible that even <strong>the</strong><br />

earliest descriptions of <strong>the</strong> vegetation may not represent what<br />

was ‘originally’ <strong>the</strong>re.<br />

The collection of quotes in this book <strong>from</strong> a diverse range<br />

of sources does make <strong>the</strong> book a valuable resource for those<br />

wanting to underst<strong>and</strong> Victoria’s vegetation. It does a good<br />

job of casting doubt on some important assumptions, <strong>and</strong><br />

although it doesn’t give <strong>the</strong> answers, we have no excuses now<br />

for continuing to rely on <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

Reviewed by Tony Faithfull<br />

In October, <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Peninsula IFFA<br />

celebrated 20 years with a lunch with many of <strong>the</strong><br />

original founding members present.<br />

Going into <strong>the</strong>ir 21st year, <strong>the</strong> group is more dynamic<br />

than ever, particularly in organising <strong>and</strong> offering<br />

community educational programs <strong>and</strong> helping to fill some<br />

of <strong>the</strong> holes in environmental education provision <strong>and</strong><br />

availability.<br />

In 2010 SPIFFA contributed in <strong>the</strong> following areas:<br />

SITE MANAGEMENT<br />

• Ongoing h<strong>and</strong>s-on management of <strong>the</strong> Cook Street block<br />

on <strong>the</strong> flank of Arthurs Seat.<br />

Environmental advocacy<br />

• Monitoring shire planning issues <strong>and</strong> commenting where<br />

appropriate;<br />

• Commenting on various shire <strong>and</strong> DSE public <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong><br />

management, fire <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r plans;<br />

• Supporting community attempts to hold public project<br />

authorities to account for lack of process, cursory<br />

ecological considerations <strong>and</strong> remediation failings;<br />

• Providing advice to members (<strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs through <strong>the</strong><br />

SPIFFA website, which averages around 35 visitors a<br />

day);<br />

• Informational networking on local <strong>and</strong> regional<br />

environmental issues through <strong>the</strong> mailing list.<br />

Education<br />

• SPIFFA provided around 110 contact teaching hours of<br />

environmental education <strong>and</strong> training, much of it free<br />

<strong>and</strong> all on a non-profit basis;<br />

• Won a grant <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> Fouress foundation to provide a<br />

series of free workshops;<br />

• Hosted <strong>the</strong> intensive Habitat Management Course for 25<br />

participants;<br />

• Hosted Dr Graeme Lorimer’s grasses ID workshop free<br />

for 16 participants;<br />

• Gidja Walker guided several free group walk <strong>and</strong> talks;<br />

• Has arranged to provide local ecological orientation <strong>and</strong><br />

information resource training for local school teachers;<br />

• Helped o<strong>the</strong>r educational efforts through presentation<br />

equipment loans, projector, screen etc;<br />

• Published SPIFFA newsletters in both hard copy <strong>and</strong><br />

on-line versions;<br />

• Continued to add new natural systems links to <strong>the</strong><br />

website links resource;<br />

• Circulated <strong>and</strong> promoted local natural systems printed<br />

information resources.<br />

IFFA congratulates SPIFFA on its very successful 20 years.<br />

(Adapted <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> SPIFFA newsletter)<br />

Hoverfly savours Trachymene<br />

composita at <strong>the</strong> Greenlink<br />

S<strong>and</strong>belt nursery in January<br />

Surf to see<br />

Here’s your chance to put a short summary of<br />

your favourite project on <strong>the</strong> web for all to see.<br />

The national journal Ecological Management &<br />

Restoration (EMR) (see www.blackwellpublishing.<br />

com/journals/emr/) is calling for very short summaries<br />

(i.e. 300 words, it can be stretched a bit) on any interesting<br />

ecosystem management or restoration project in Australia, i.e.<br />

projects that are already showing good results.<br />

These will be published on a new website which will be part<br />

of <strong>the</strong> journal’s permanent publication output.<br />

There is no limit to <strong>the</strong> number of short summaries of case<br />

studies that EMR can publish — <strong>and</strong> now that <strong>the</strong>y are on <strong>the</strong><br />

web — we can include a couple of coloured photo or maps<br />

per summary.<br />

All you need to do is email me something <strong>and</strong> we can see<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r it will meet <strong>the</strong> criteria. If it does, I can help edit it<br />

down to 300 words for publication <strong>and</strong> help you select photos.<br />

(See specifications below.)<br />

If you have a range of projects that qualify, that is even<br />

better. Please send a few if you like <strong>and</strong> we can group <strong>the</strong>m<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r!.<br />

Please submit your drafts or ideas for summaries as<br />

soon as possible so you can catch <strong>the</strong> launch in April. Later<br />

submissions are also fine, as we will be regularly updating <strong>the</strong><br />

website.’<br />

Tein McDonald<br />

teinm@ozemail.com.au<br />

4 INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC INDIGENOTES VOLUME 22 NUMBER 1<br />

5

School frog pond <strong>and</strong><br />

bush tucker garden<br />

Beginnings<br />

The idea for <strong>the</strong> frog pond <strong>and</strong> bush tucker<br />

garden came out of <strong>the</strong> Sustainability Framework<br />

that Brunswick East Primary School (BEPS) is<br />

working through to gain 5-star accreditation as a<br />

Sustainable School.<br />

The site at <strong>the</strong> bottom of <strong>the</strong> Colourful Playground on <strong>the</strong><br />

north side of <strong>the</strong> school was chosen as it was closest to Jones<br />

Park pond <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Merri Creek where we hope frogs will<br />

migrate <strong>from</strong>, <strong>and</strong> we could use water <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> newly installed<br />

rainwater tanks to fill <strong>the</strong> pond during dry seasons.<br />

Heavy Gardening groups <strong>from</strong> grades 4, 5 <strong>and</strong> 6 began<br />

preparing <strong>the</strong> site in term 2, 2009, clearing posts, pruning<br />

trees <strong>and</strong> measuring <strong>the</strong> area for <strong>the</strong> design.<br />

Parents contributed <strong>the</strong>ir skills through surveying <strong>the</strong> site,<br />

<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>scape design, construction <strong>and</strong> grant writing.<br />

BEPS was successful in applying for <strong>and</strong> receiving two<br />

grants through L<strong>and</strong>care, one for <strong>the</strong> Frog Pond <strong>and</strong> one for<br />

a Bush Tucker Garden. The grants contributed two thous<strong>and</strong><br />

dollars to <strong>the</strong> cost of construction <strong>and</strong> materials.<br />

Construction<br />

An excavator came in during Term 2 holidays <strong>and</strong> dug<br />

<strong>the</strong> frog pond<br />

<strong>and</strong> moved<br />

soil <strong>and</strong> rocks.<br />

Construction<br />

continued through<br />

Term 3 with <strong>the</strong><br />

Light <strong>and</strong> Heavy<br />

Gardening groups<br />

<strong>from</strong> grades 4, 5<br />

<strong>and</strong> 6 creating <strong>the</strong><br />

paths <strong>and</strong> pond<br />

surround, putting<br />

up bamboo<br />

fencing, moving<br />

mulch for <strong>the</strong><br />

path surfaces,<br />

turning <strong>the</strong> soil for garden beds,<br />

weeding <strong>and</strong> digging posts for<br />

<strong>the</strong> fence.<br />

The frog pond <strong>and</strong><br />

habitat link in<br />

February 2011.<br />

Planting<br />

This part of <strong>the</strong> project involved <strong>the</strong> whole<br />

school. The frog incursion run by Waterwatch<br />

happened in Week 8 <strong>the</strong>n all classes came out<br />

during <strong>the</strong> following week to plant <strong>the</strong> bush tucker<br />

garden around <strong>the</strong> frog pond.<br />

Preparation for <strong>the</strong> planting started in Term 2<br />

when a number of classes propagated <strong>from</strong> seed<br />

<strong>the</strong> Murnong (Yam Daisy) that used to flourish<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Merri Creek catchment <strong>and</strong> was a staple food of <strong>the</strong><br />

indigenous peoples. The seeds germinated <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> seedlings<br />

were planted along with o<strong>the</strong>r plants purchased for <strong>the</strong> garden<br />

<strong>and</strong> water plants for <strong>the</strong> frog pond.<br />

With help <strong>from</strong> parents, over 400 plants were put in<br />

during our planting week, including Chocolate Lilies,<br />

Kangaroo Grass, Spiny-headed Mat Rush <strong>and</strong> Nardoo. The<br />

emphasis was on indigenous plants <strong>and</strong> ones that could be<br />

used for food, tools or materials.<br />

Filling <strong>the</strong> pond<br />

The frog pond was initially filled <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> rain water tanks<br />

attached to <strong>the</strong> school’s toilet block. The pond will continue<br />

to be filled <strong>from</strong> this source, as required, as <strong>the</strong>re is no natural<br />

run-off into <strong>the</strong> pond. During <strong>the</strong> heavy rain Melbourne<br />

has received recently, <strong>the</strong> pond has flooded <strong>the</strong> surrounding<br />

plantings (Centipedia cunninghamii, Isolepis<br />

nodosa, Mentha australis, Triglochin procera<br />

<strong>and</strong> Microphyllum crispatum).<br />

No frogs have made <strong>the</strong> pond <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

home, as yet, but it is a great talking point<br />

amongst <strong>the</strong> children about when <strong>the</strong>y will<br />

arrive. There is a very vocal Pobblebonk<br />

population in a nearby pond who may<br />

need to exp<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir territory due to ideal<br />

breeding conditions.<br />

We are hopeful!<br />

The enthusiasm of<br />

<strong>the</strong> children has been<br />

wonderful to see. The<br />

addition of a small, safe<br />

body of water in <strong>the</strong> school<br />

grounds has added an<br />

experience for many of <strong>the</strong><br />

children <strong>the</strong>y may not have<br />

regularly.<br />

The school passes on<br />

a very big thank you to<br />

Jane Beve<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>er <strong>from</strong><br />

Waterwatch whose initial<br />

advice <strong>and</strong> ongoing interest<br />

has been invaluable, also<br />

a very big thank you to<br />

Dave Crawford <strong>from</strong><br />

MECCARG for advice on <strong>the</strong> Murnong, <strong>and</strong> thank you to<br />

<strong>the</strong> staff at MCMC <strong>and</strong> VINC for advice on our indigenous<br />

plants.<br />

IFFA congratulates everyone who contributed to <strong>the</strong> new<br />

garden <strong>and</strong> frog pond at <strong>the</strong> school.<br />

Photos <strong>and</strong> text by Tania Sloan<br />

Clockwise <strong>from</strong> top left: Finger flower, Cheiran<strong>the</strong>ra cyanea; Chocolate<br />

Lily, Arthropodium strictum, with a weed Quaking Grass, Briza maxima;<br />

Blue Pincushions, Brunonia australis; Fringe Lily, Thysanotus tuberosus;<br />

Sticky Everlasting, Xerochrysum viscosum.<br />

Observations <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> Great Victorian Bike Ride<br />

Each year <strong>the</strong> GVBR travels through rural Victoria, mostly<br />

on quiet roads. Though most participants view this ride<br />

as an end in itself, it also allows <strong>the</strong> riders to view <strong>the</strong><br />

countryside in some detail (compared to travelling <strong>the</strong><br />

same roads by car). In particular <strong>the</strong> rider gets to see around<br />

600kms of roadside verges, important refuges of Victoria’s<br />

remnant vegetation.<br />

In 2010 <strong>the</strong> ride started <strong>from</strong> Yarrawonga <strong>and</strong> finished at<br />

Marysville. The first overnight stop was at Dookie where <strong>the</strong> Seed<br />

Bank provided a tour of <strong>the</strong>ir facility. It was fascinating to see<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir harvesting equipment (for Austrodanthonia <strong>and</strong> Themeda),<br />

drying racks <strong>and</strong> bulk bags of grasses packaged for VicRoads<br />

(to be sprayed on road cuttings). The small <strong>and</strong> dedicated staff<br />

seem to be operating under an extreme funding shortfall, with<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir refrigeration equipment broken down <strong>and</strong> unable to be<br />

repaired. The area was notable for some excellent st<strong>and</strong>s of<br />

Dianella longifolia, Austrostipa, Chrysocephalum, Arthropodium<br />

strictum <strong>and</strong> Themeda. Possibly <strong>the</strong> best spots for wildflowers<br />

were between Yea <strong>and</strong> Eildon where I stopped to photograph<br />

Thysanotus, Chamaescilla <strong>and</strong> Arthropodium.<br />

Apart <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> GVBR, I also rode <strong>the</strong> Ballarat to Skipton rail<br />

trail <strong>and</strong> was impressed with <strong>the</strong> amount of remnant vegetation<br />

along <strong>the</strong> route. Large patches of Burchardia, Dianella, Craspedia<br />

were present, as well as many orchids such as Thelymitra in flower.<br />

Perhaps cycling will become a mainstream activity among field<br />

naturalists?<br />

Doug Scott<br />

Member of Whitehorse Community <strong>Indigenous</strong> Plants Project.<br />

6<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC INDIGENOTES VOLUME 22 NUMBER 1<br />

7

Looking after <strong>the</strong> bush<br />

Natural regeneration is better than planting<br />

Jeff Yugovic<br />

Well-intended but inappropriate planting<br />

has occurred within native vegetation for many<br />

years. However, planting has become more of<br />

an issue recently due to <strong>the</strong> Native Vegetation<br />

Management Framework (NRE 2002) which<br />

is Victorian government policy requiring an<br />

‘offset’ for legally permitted clearing of native<br />

vegetation.<br />

Offsets usually include ‘recruitment’ plants which are<br />

in practice mostly planted ra<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

obtained by natural regeneration, although<br />

natural regeneration is allowable under <strong>the</strong><br />

policy. Where planting occurs within native<br />

vegetation it is referred to as ‘supplementary<br />

planting’.<br />

Inappropriate planting reduces <strong>the</strong><br />

ecological integrity of native vegetation. If<br />

it is an offset site this only adds to <strong>the</strong> total<br />

impact given that <strong>the</strong> site generating <strong>the</strong> offset<br />

was cleared in <strong>the</strong> first place. Consequently,<br />

remnant native vegetation is under significant<br />

threat <strong>from</strong> poorly conceived or applied offsets<br />

throughout Victoria. Here I give examples of<br />

adverse impacts followed by a discussion on<br />

how to avoid this problem, which is basically<br />

to avoid planting in native vegetation except in<br />

certain circumstances. Native vegetation is best<br />

managed by weeding <strong>and</strong> facilitating natural<br />

regeneration.<br />

Inappropriate species<br />

Recently I came across a conservation<br />

reserve south-east of Melbourne supporting<br />

grassy wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>, swampy wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>and</strong> swamp scrub<br />

vegetation. From <strong>the</strong> age of some trees, planting appears to<br />

have been going on for some years. As part of an offset for<br />

vegetation cleared elsewhere, plants were also recently planted<br />

within part of <strong>the</strong> reserve. These plantings were placed within<br />

plastic tree guards, which at least made <strong>the</strong>m easy to recognise.<br />

Unfortunately, few or none of <strong>the</strong> plantings were<br />

appropriate. In particular, species that do not naturally occur<br />

in <strong>the</strong> reserve were planted, including Messmate Stringybark<br />

Facilitated natural recruitment<br />

is <strong>the</strong> preferred means of<br />

obtaining new plants<br />

Eucalyptus obliqua (Figure 1). Some E. obliqua seedlings<br />

were planted below existing mature Silver-leaf Stringybark,<br />

Eucalyptus cephalocarpa, <strong>and</strong> Swamp Gum, Eucalyptus ovata.<br />

Such plantings below or near existing trees compete with <strong>and</strong><br />

stress <strong>the</strong>se trees, or else fail <strong>and</strong> waste resources. They also<br />

undermine <strong>the</strong> ecological integrity of <strong>the</strong> site, turning it into a<br />

plantation ra<strong>the</strong>r than au<strong>the</strong>ntic self-sown natural vegetation<br />

that has undergone natural selection.<br />

Species that occur within <strong>the</strong> reserve were also planted<br />

outside <strong>the</strong>ir natural habitat within <strong>the</strong> reserve, such as<br />

Common Tussock-grass, Poa labillardierei, in grassy wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong><br />

where none naturally occurs. Not surprisingly many of <strong>the</strong><br />

plantings died, particularly <strong>the</strong> Poa as it needs more moisture<br />

than is generally available in grassy wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>, especially<br />

during drought. The correct Poa for <strong>the</strong> site is Soft Tussockgrass,<br />

Poa morrisii, which is already present.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r reserve in sou<strong>the</strong>rn Melbourne was identified as<br />

an offset site for clearing elsewhere. In this case <strong>the</strong> natural<br />

vegetation is plains grassy wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> dominated by River Redgum,<br />

Eucalyptus camaldulensis. The proposal was to extensively<br />

Figure 1. Messmate Stringybark planted where it does not naturally occur.<br />

plant <strong>the</strong> reserve with shrubs. Firstly some of <strong>the</strong>se shrubs do<br />

not naturally occur in this plant community in this area, <strong>and</strong><br />

secondly <strong>the</strong> vegetation is a grassy wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> not a shrubby<br />

wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>and</strong> such plantings may stress <strong>the</strong> existing trees.<br />

Fortunately <strong>the</strong> management agency recognised <strong>the</strong> risk <strong>and</strong><br />

prevented <strong>the</strong> planting. Many more sites are subject to such<br />

disastrous proposals.<br />

Naturally treeless grass<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s are often at risk of misguided<br />

tree planting, in both nor<strong>the</strong>rn <strong>and</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn Victoria, for<br />

example in a flora reserve near Echuca, where tree planting<br />

has occurred, possibly over endangered Red Swainson-pea,<br />

Swainsona plagiotropis.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r issues<br />

There are o<strong>the</strong>r issues with planting besides introducing<br />

species that are not site-indigenous.<br />

The identity of plants used in planting can be an issue. The<br />

species may not be <strong>the</strong> one intended due to misidentification<br />

during <strong>the</strong> collection of propagation material or some o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

mistake in <strong>the</strong> nursery. A classic example is <strong>the</strong> planting of<br />

South African Angled Pigface, Carpobrotus aequilaterus, instead<br />

of Karkalla (Pigface), Carpobrotus rossii, in coastal revegetation.<br />

Angled Pigface is widely naturalised as a result.<br />

The provenance of species, even if <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>the</strong> correct<br />

species for <strong>the</strong> site, can be an issue. Non-Victorian forms of<br />

Spiny-headed Mat-rush, Lom<strong>and</strong>ra longifolia, are often seen<br />

in plantings <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y perform poorly in drought conditions,<br />

affecting <strong>the</strong> reputation of indigenous plants. The provenance<br />

should be <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> same or similar geology <strong>and</strong> climate.<br />

The issue of local versus non local provenance has long<br />

been debated (see Hufford & Mazer (2003) <strong>and</strong> McKay<br />

et al. (2005)). However, that debate important as it<br />

is, assumes <strong>the</strong> actual species are correct for <strong>the</strong> site<br />

(site-indigenous). This article makes <strong>the</strong> point that <strong>the</strong><br />

species <strong>the</strong>mselves can be inappropriate, which is more<br />

fundamental than <strong>the</strong> provenance question.<br />

Site preparation for planting can be damaging to<br />

existing native vegetation. Spraying <strong>and</strong> mulching can<br />

kill or smo<strong>the</strong>r native plants, native grasses frequently<br />

being affected. This is also likely to promote weeds.<br />

One site in sou<strong>the</strong>rn Melbourne was heavily mulched,<br />

killing wallaby-grass, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n planted with Manna<br />

Gum, Eucalyptus vimimalis, where only Swamp Gum,<br />

Eucalyptus ovata, naturally occurs. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, seedlings were<br />

planted below <strong>the</strong> canopy of <strong>the</strong> existing trees, where <strong>the</strong>y will<br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r die or compete with <strong>the</strong> trees.<br />

Spraying herbicide during <strong>the</strong> maintenance of plantings<br />

can damage existing indigenous species. For example in one<br />

reserve herbicide was applied around <strong>the</strong> plantings (Figure 2)<br />

Figure 2. Sprayed, now dead, indigenous Weeping Grass around a planting.<br />

apparently even where one of <strong>the</strong> plants was dead <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> tree<br />

guard had fallen over. This killed areas of indigenous Weeping<br />

Grass, Microlaena stipoides. Weeds such as Panic Veldt-grass,<br />

Ehrharta erecta, subsequently established within <strong>the</strong> bare areas,<br />

increasing <strong>the</strong> impact.<br />

In many cases planted tubestock contains nursery weeds<br />

in <strong>the</strong> tube soil <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>se can be introduced into native<br />

vegetation. Common nursery weeds often found in tubestock<br />

include G<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>ular Willow-herb, Epilobium ciliatum, Creeping<br />

Wood-sorrel, Oxalis corniculata, <strong>and</strong> Annual Meadow-grass,<br />

Poa annua. Good nursery management should prevent this.<br />

The genetic quality of propagated material may be an issue<br />

but it is poorly understood. Eucalypt seed collected <strong>from</strong> a<br />

single isolated tree is likely to have a high proportion of inbred<br />

seed. If <strong>the</strong>y germinate, inbred seedlings of species with a high<br />

‘genetic load’ of mutations are likely to be weak <strong>and</strong> would<br />

tend to die out in nature, but in optimal nursery conditions<br />

<strong>the</strong>y may survive <strong>and</strong> be planted out. Nursery propagation can<br />

<strong>the</strong>refore bypass <strong>the</strong> early stages of <strong>the</strong> plant life cycle which<br />

are an important part of natural selection.<br />

We would not allow unsupervised<br />

people into <strong>the</strong> art gallery to restore<br />

<strong>the</strong> collection with polyfilla <strong>and</strong> dulux,<br />

we should not allow botched attempts<br />

at bush<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> restoration<br />

Natural recruitment is better than planting<br />

Natural recruitment is preferred to planting because <strong>the</strong><br />

result is au<strong>the</strong>ntic site-indigenous native vegetation that has<br />

undergone natural selection ra<strong>the</strong>r than an anthropogenic<br />

plantation.<br />

Inappropriate planting related to <strong>the</strong> Native Vegetation<br />

Management Framework could be averted<br />

if <strong>the</strong> recruitment were to be obtained by<br />

natural regeneration only, which is allowable<br />

under <strong>the</strong> Framework but not usually<br />

undertaken. This would mean that <strong>the</strong> plants<br />

are site-indigenous, assuming <strong>the</strong>y are not<br />

<strong>the</strong> progeny of wrong plantings <strong>the</strong>mselves.<br />

However, some sites do not need additional<br />

plants, such as many grassy wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>s where<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is already too much biomass due to<br />

lack of fire or grazing, <strong>and</strong> additional plants<br />

may fur<strong>the</strong>r shade out species diversity. There<br />

are also implications for fauna as <strong>the</strong> habitat<br />

becomes more woody <strong>and</strong> overgrown.<br />

Planting is usually undertaken ra<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

facilitated natural recruitment, <strong>and</strong> seedlings<br />

in tree guards are now all too familiar within<br />

bush<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>. It is simpler <strong>and</strong> sometimes<br />

cheaper to plant ra<strong>the</strong>r than to manage a site<br />

over several years to facilitate recruitment.<br />

This is called ‘tree guard dreaming’ by<br />

botanist Geoff Carr.<br />

When planting is appropriate<br />

Revegetation (planting or direct seeding) on cleared<br />

<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> with predominantly introduced vegetation does not<br />

affect existing native vegetation, but <strong>the</strong> species should be<br />

site-indigenous. If a site is next to native vegetation, natural<br />

colonisation is preferred to planting.<br />

Supplementary planting (or direct seeding) within<br />

native vegetation can be appropriate where <strong>the</strong>re is little or<br />

no potential for natural recruitment of <strong>the</strong> species, ei<strong>the</strong>r<br />

where (a) <strong>the</strong> species is site-extinct or (b) appropriate site<br />

management has not resulted in regeneration <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> species<br />

is not waiting for a natural episodic event such as flood or fire.<br />

8 INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC INDIGENOTES VOLUME 22 NUMBER 1<br />

9

Alternatively <strong>the</strong>re may be a <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> protection reason<br />

where vegetation cover is needed in <strong>the</strong> short term,<br />

for example planting site-indigenous scramblers on<br />

a slope exposed by woody weed removal.<br />

Amenity <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>scape plantings of locally indigenous species<br />

are fine <strong>and</strong> appropriate around infrastructure such as<br />

buildings <strong>and</strong> carparks, but plantings within <strong>the</strong> core of a<br />

reserve should be strictly site-indigenous. A clear distinction<br />

should be made between locally indigenous species, which<br />

may occur in any plant community in <strong>the</strong> local area, <strong>and</strong> siteindigenous<br />

species, which are indigenous to <strong>the</strong> site itself.<br />

Site-indigenous principle<br />

Where planting is within introduced vegetation, or where<br />

planting within native vegetation is appropriate (as above),<br />

it should be site-indigenous o<strong>the</strong>rwise <strong>the</strong> result is strictly<br />

horticulture ra<strong>the</strong>r than revegetation. Determining what is<br />

site-indigenous has two aspects:<br />

• Firstly it is necessary to determine <strong>the</strong> natural plant<br />

community of <strong>the</strong> site. In <strong>the</strong> terminology of <strong>the</strong> state<br />

government (DSE) this is <strong>the</strong> floristic community of <strong>the</strong><br />

ecological vegetation class (EVC). The DSE biodiversity<br />

interactive map indicates <strong>the</strong> EVCs that occur in <strong>the</strong> local<br />

area, but <strong>the</strong> mapping, whilst it is a valuable introduction, is<br />

not always accurate. Several more EVCs may be present in a<br />

local area than is indicated, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> EVC boundaries may not<br />

be correct, noting <strong>the</strong> mapping is only at 1:100,000. A range<br />

of evidence may be required including observations on <strong>the</strong><br />

existing vegetation of <strong>the</strong> site <strong>and</strong> adjacent sites, interpretation<br />

of geology maps, <strong>and</strong> review of historical survey plans. It is<br />

important that an expert with local knowledge is consulted.<br />

• Secondly it is necessary to determine <strong>the</strong> species composition<br />

of <strong>the</strong> plant community once it is identified. This requires<br />

knowledge of <strong>the</strong> local vegetation as <strong>the</strong>re is no comprehensive<br />

guide for most of Victoria. The EVC benchmarks provided by<br />

DSE are valuable in underst<strong>and</strong>ing EVC vegetation but <strong>the</strong>y<br />

only give a short list of some typical species. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, not<br />

every species within an EVC occurs on every site, for example<br />

Snow Gum Eucalyptus pauciflora has restricted occurrences<br />

within grassy wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>. Some local governments have fairly<br />

accurate EVC planting guides based on detailed analysis of<br />

vegetation data <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir areas, but o<strong>the</strong>rs have little or no<br />

such information.<br />

Assisting migration due to climate change<br />

Species that would ‘migrate’ across <strong>the</strong> <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>scape due to<br />

climate change but are unable to do so because of barriers such<br />

as extensive cleared <strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> could be introduced to new areas.<br />

This has not been undertaken to my knowledge but may be<br />

appropriate in future.<br />

Need for expertise<br />

Consultants who prepare offset management plans <strong>and</strong><br />

bush<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> management contractors who implement <strong>the</strong>se<br />

plans require a high level of training <strong>and</strong> experience in order to<br />

produce ecologically sound plans <strong>and</strong> achieve good results on<br />

<strong>the</strong> ground. Professional development of practitioners in <strong>the</strong>se<br />

areas should be encouraged <strong>and</strong> supported at all times. We<br />

should also forgive (but not forget) management mistakes, as<br />

we all make <strong>the</strong>m at times.<br />

Native vegetation is too valuable to<br />

be subject to inappropriate planting<br />

Dealing with poor attempts at revegetation<br />

Substantial areas of ‘revegetation’ often occur within <strong>and</strong> on<br />

<strong>the</strong> edges of reserves but many of <strong>the</strong> plantings are not <strong>the</strong> original<br />

species of <strong>the</strong> site so strictly speaking <strong>the</strong>se plantings constitute<br />

horticulture <strong>and</strong> not revegetation. Many reserves are too small<br />

to accommodate horticulture <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> emphasis should be on<br />

conservation <strong>and</strong> natural regeneration of <strong>the</strong> native vegetation.<br />

In <strong>the</strong>se cases all planting should cease <strong>and</strong> natural recruitment<br />

should be facilitated to obtain new plants. Conservation reserves<br />

should support au<strong>the</strong>ntic self-sown natural vegetation <strong>and</strong> should<br />

not become gardens or anthropogenic plantations.<br />

Inappropriate plantings <strong>and</strong> progeny of such plantings<br />

should be removed, while site-indigenous plantings <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

progeny should be retained. This requires a good underst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

of <strong>the</strong> distribution of each plant community within an area<br />

<strong>and</strong> species composition of each plant community. In areas<br />

where ‘revegetation’ has taken place a review of <strong>the</strong> revegetation<br />

should be undertaken. The political sensitivity of this issue is<br />

acknowledged as <strong>the</strong>re may be people who have worked hard with<br />

good intentions but whose work has been counterproductive to<br />

conservation due to limited knowledge of <strong>the</strong> vegetation. These<br />

people should participate in reviews <strong>and</strong> in any corrective actions<br />

if possible.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Native vegetation is too valuable to be subject to<br />

inappropriate planting <strong>and</strong> maintenance of plantings. Every<br />

site is unique in terms of its intrinsic site characteristics<br />

(geology, climate, aspect, slope, drainage etc) <strong>and</strong> its site<br />

history (disturbance, colonisation events etc) <strong>and</strong> consequently<br />

in terms of its species composition <strong>and</strong> should be treated<br />

accordingly.<br />

Facilitated natural recruitment is <strong>the</strong> preferred means of<br />

obtaining new plants, with planting a last resort that needs<br />

careful consideration. Vegetation management should be based<br />

on good knowledge of local vegetation <strong>and</strong> its requirements in<br />

order to ensure its ecological integrity.<br />

Patches of remnant native vegetation may be regarded<br />

as local ecological masterpieces of nature. Just as we would<br />

not allow unsupervised people into <strong>the</strong> art gallery to restore<br />

<strong>the</strong> collection with polyfilla <strong>and</strong> dulux, we should not allow<br />

botched attempts at bush<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> restoration. A scientific <strong>and</strong><br />

informed approach to vegetation management is called<br />

for, based on weeding, facilitated natural regeneration <strong>and</strong><br />

appropriate supplementary planting.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Thanks to Steve Sinclair, Matt Dell, Gidja Walker, Jill Anderson <strong>and</strong><br />

Sue McIntyre for comments <strong>and</strong> suggestions.<br />

References<br />

Hufford, K.M. & Mazer, S.J. (2003). Plant ecotypes: genetic<br />

differentiation in <strong>the</strong> age of ecological restoration. Trends in Ecology<br />

<strong>and</strong> Evolution 18: 147–155.<br />

McKay, J.K., Christian, C.E., Harrison, S. & Rice K.J. (2005).‘‘How<br />

local is local?’’ — A review of practical <strong>and</strong> conceptual issues in <strong>the</strong><br />

genetics of restoration. Restoration Ecology 13: 432–440.<br />

NRE (2002). Victoria’s Native Vegetation Management: A Framework<br />

for Action. Department of Natural Resources & Environment, Victoria.<br />

Review<br />

Mistletoes of Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Australia<br />

David Watson<br />

CSIRO Publishing<br />

$49.95<br />

188 pages, colour plates <strong>and</strong> photographs.<br />

Mistletoes are widely misunderstood. I<br />

frequently have to defend <strong>the</strong>se much maligned<br />

plants so I rejoiced at <strong>the</strong> arrival of this charming<br />

<strong>and</strong> intriguing book by David Watson.<br />

The book engages <strong>the</strong> reader on many levels. The largest<br />

part is a description of each of <strong>the</strong> 46 species of mistletoe<br />

found in Australia south of <strong>the</strong> 26th latitude (i.e. a line<br />

running <strong>from</strong> Fraser<br />

Is<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong> in Queens<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong><br />

to Shark Bay in<br />

W.A. <strong>and</strong> following<br />

<strong>the</strong> South Australia/<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Territory<br />

border). This is out of<br />

a total of 91 currently<br />

recognised species in<br />

Australia. These are<br />

attractively presented<br />

double-page accounts<br />

with a watercolour<br />

showing details of <strong>the</strong><br />

plant <strong>and</strong> a page of<br />

text with colour photo<br />

<strong>and</strong> Australia-wide<br />

distribution map.<br />

Chapters on mistletoe<br />

evolution <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

considerable ecological<br />

importance, are<br />

complemented with<br />

fascinating accounts of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir cultural significance<br />

(both Australian <strong>and</strong><br />

overseas) medicinal,<br />

Drooping Mistletoe, Amyema<br />

pendula, distinguished <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

similar Box Mistletoe by <strong>the</strong> way<br />

<strong>the</strong> central flower is stalkless<br />

in each group of three flowers.<br />

One important ecological aspect<br />

of Mistletoes brought out in <strong>the</strong><br />

book is <strong>the</strong> reliable nectar <strong>and</strong><br />

fruit resource that mistletoes<br />

provide. This picture was taken in<br />

Longwood East in September.<br />

culinary <strong>and</strong> even artistic depictions. The book will have<br />

broader appeal than as simply an identification guide.<br />

The ‘darker’ side of mistletoe is covered in a chapter on<br />

management. The origin <strong>and</strong> degree of threat that mistletoe<br />

can present to trees in <strong>the</strong> context of fragmented natural<br />

<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>scapes is defined. Human aversion to <strong>the</strong>ir parasitic ways<br />

has contributed to persecution, often out of all proportion to<br />

specific threat involved. This book will be valuable to those<br />

(in particular in <strong>the</strong> arborist profession) facing <strong>the</strong> dilemma<br />

of trying to balance <strong>the</strong> ecological benefits of retaining<br />

mistletoes <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> inevitable toll this may take on individual<br />

trees. Methods of controlling mistletoe are provided with<br />

advice on seeking to underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> root cause of any<br />

perceived over-abundance. But <strong>the</strong>re are also descriptions<br />

of conservation priorities <strong>and</strong> instructions for planting<br />

mistletoes in patches of restored wood<strong>l<strong>and</strong></strong>: an intriguing<br />

avenue of experimentation.<br />

The book will be enjoyed by anyone interested in our<br />

native environment.<br />

Brian Bainbridge<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Association</strong><br />

Victoria’s biodiversity thriving<br />

<strong>and</strong> valued by all<br />

http://www.iffa.org.au<br />

Incorporated <strong>Association</strong> No: A0015723B<br />

Office Bearers<br />

President: Brian Bainbridge, 7 Jukes Rd Fawkner 3060 (03)<br />

9359 0290(ah) email: president@iffa.org.au<br />

Vice-President: Vanessa Craigie, email: vicepres@iffa.org.au,<br />

phone 94973730 (ah).<br />

Secretary: Michele Arundell PO Box 77, Kallista 3791.<br />

(03) 9755 3347 (ah) email: secretary@iffa.org.au<br />

Treasurer: Ranbir Baath, 0423 274 777.<br />

email: treasurer@iffa.org.au<br />

Committee members: Liz Henry, (03) 9890 4542,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Lawrie Hanson<br />

Public Officer: Peter Wlodarzyck, 0418 317 725<br />

email: publicofficer@iffa.org.au<br />

Events Coordinator: Linda Bradburn, 6 Stephen Street, West<br />

Preston, (03) 9416 7184(ah), email activities@iffa.org.au.<br />

Newsletter Editor: Tony Faithfull, (03) 9386 0264 (ah).<br />

21 Harrison St East Brunswick 3057. editor@iffa.org.au<br />

Webmaster: vacant<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> Nurseries Liaison Officer: vacant<br />

Youth representative: Karen McGregor, email<br />

k.mcgregor3@ugrad.unimelb.edu.au<br />

Fundraising Coordinator: vacant<br />

Ecological Information Coordinator: vacant<br />

Indigenotes is <strong>the</strong> newsletter of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Flora</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Association</strong>.<br />

The views expressed in Indigenotes are not necessarily those<br />

of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Flora</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Fauna</strong> <strong>Association</strong>.<br />

Call for articles<br />

Indigenotes is a newsletter by IFFA members for IFFA members.<br />

Stories, snippets, photos, reports <strong>from</strong> members are always<br />

welcome.<br />

If it’s something you’re doing with flora or fauna or habitat, write it<br />

down <strong>and</strong> send it to IFFA’s editor at editor@iffa.org.au.<br />

Membership<br />

$40 per annum for non-profit organizations,<br />

$50 per annum for corporations,<br />

$25 per annum for individuals, or $20 per annum concession,<br />

$30 per annum for families,<br />

$500 for individual life members or<br />

$700 for family life members.<br />

Membership includes<br />

4 issues of Indigenotes per year,<br />

Occasional freebies or discounts<br />

•<br />

Discount subscription to Ecological Management &<br />

Restoration Journal ($70.40, inc GST)<br />

Membership applications <strong>and</strong> renewals should be sent to <strong>the</strong><br />

Secretary, Post Office Box 77 Kallista 3791.<br />

INDIGENOUS FLORA AND FAUNA ASSOCIATION INC INDIGENOTES VOLUME 22 NUMBER 1<br />

10 11

A Spider Wasp, Turneromyia sp, drags a Huntsman Spider, Isopeda<br />

montana, which it has paralysed into a burrow. The wasp will lay an<br />

egg on <strong>the</strong> spider before filling <strong>the</strong> entrance to <strong>the</strong> burrow. The newly<br />

hatched wasp larva will feed on <strong>the</strong> spider’s body <strong>and</strong> eventually<br />

emerge <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> burrow as a new adult. All this is happening two<br />

metres <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> back door in a suburban back yard in Hughesdale.<br />

29 December 2010. Photos: Mick Connolly<br />

Contents<br />

A garden education 2-3<br />

IFFA excursion details 3<br />

What’s Natural? Book review 4<br />

Snippets5 Looking after <strong>the</strong> bush 8-10<br />

School’s in INDIGENOUS 6 FLORA Mistletoes AND FAUNA book review; ASSOCIATION INC<br />

Biking spin-off 7 contact us 11