Life Nature Magazine

themed ‘Dusk until Dawn’. These times are to me, some of the most exciting to experience wildlife. When I can make it out of bed in time for dawn, the chorus of birds chattering and singing above me makes the wrestle with my tiredness all worth it. As sun sets, some of the most secretive animals come out of their day time hiding places. Foxes and badgers can be seen by the lucky, and bats’ sonar can be heard with a handy bat detector. The time between dusk and dawn is fascinating too. Whilst most of us are tucked up in bed asleep, many animals are exploiting this quieter period, with multitudes of adaptations allowing them to use the darkness to their advantage. From this issue, many of the original team, including myself, are ‘phasing out’. We’re looking for new team members – see the careers section for more information on how to get involved. Whilst some of us will still be involved in the next issue, we’ll be taking less on, so we’d like to thank

themed ‘Dusk until Dawn’.

These times are to me, some of

the most exciting to experience

wildlife. When I can make it

out of bed in time for dawn,

the chorus of birds chattering

and singing above me makes

the wrestle with my tiredness

all worth it. As sun sets, some of

the most secretive animals come

out of their day time hiding

places. Foxes and badgers can

be seen by the lucky, and bats’

sonar can be heard with a handy

bat detector. The time between

dusk and dawn is fascinating

too. Whilst most of us are

tucked up in bed asleep, many

animals are exploiting this

quieter period, with multitudes

of adaptations allowing them

to use the darkness to their

advantage. From this issue,

many of the original team,

including myself, are ‘phasing

out’. We’re looking for new

team members – see the careers

section for more information

on how to get involved. Whilst

some of us will still be involved

in the next issue, we’ll be taking

less on, so we’d like to thank

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

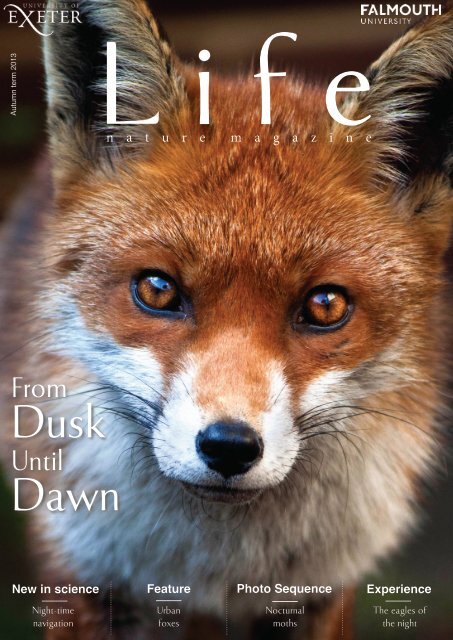

Autumn term 2013<br />

i f e<br />

n a t u r e m a g a z i n e<br />

From<br />

Dusk<br />

Until<br />

Dawn<br />

New in science<br />

Feature<br />

Photo Sequence<br />

Experience<br />

Night-time<br />

navigation<br />

Urban<br />

foxes<br />

Nocturnal<br />

moths<br />

The eagles of<br />

the night

A big THANKS!<br />

We’re looking for a new team to join <strong>Life</strong>, so here’s a massive thank you to everyone who<br />

<br />

Editor in Chief: Roz Evans<br />

Creative Director: Emma Simpson-Wells<br />

Sub-Creative Directors: Georgia Cass & Andy Jackson<br />

Picture Editors: Samuel Jay & Charlotte Sams<br />

Great thanks for input and ongoing advice is owed to:<br />

Felix Smith, Feargus Cooney, Owen Greenwood, Jennifer Weller, Matt Bjerregaard and<br />

Claire Young.<br />

Gemma Malenoir is a 20 year old student, studying<br />

in her third year of BA (Hons) Marine and Natural History<br />

Photography, at Falmouth University, Cornwall. Check out<br />

her work at:<br />

www.gemmamalenoir.carbonmade.com<br />

2

FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

From Dusk Until Dawn...<br />

Contents<br />

The third issue of <strong>Life</strong> is<br />

themed ‘Dusk until Dawn’.<br />

These times are to me, some of<br />

the most exciting to experience<br />

wildlife. When I can make it<br />

out of bed in time for dawn,<br />

the chorus of birds chattering<br />

and singing above me makes<br />

the wrestle with my tiredness<br />

all worth it. As sun sets, some of<br />

the most secretive animals come<br />

out of their day time hiding<br />

places. Foxes and badgers can<br />

be seen by the lucky, and bats’<br />

sonar can be heard with a handy<br />

bat detector. The time between<br />

dusk and dawn is fascinating<br />

too. Whilst most of us are<br />

tucked up in bed asleep, many<br />

animals are exploiting this<br />

quieter period, with multitudes<br />

of adaptations allowing them<br />

to use the darkness to their<br />

advantage. From this issue,<br />

many of the original team,<br />

including myself, are ‘phasing<br />

out’. We’re looking for new<br />

team members – see the careers<br />

section for more information<br />

on how to get involved. Whilst<br />

some of us will still be involved<br />

in the next issue, we’ll be taking<br />

less on, so we’d like to thank<br />

<br />

few issues so warmly. We’ve had<br />

an amazing time making it and<br />

we hope that it continues from<br />

strength to strength!<br />

Enjoy!<br />

Roz Evans, Editior in Chief<br />

4 Image of the issue<br />

Exeter Research<br />

6 Garden snails go viral<br />

New in science<br />

8 Iron beaks and magnetic eyes<br />

10 Swiftly rising at dawn and dusk<br />

Evolution<br />

12 Coevolution of bats and moths<br />

Photograph sequence<br />

of the issue<br />

14 Moths at twilight<br />

<br />

18 Ageing badgers<br />

Experience<br />

20 Eagle owls up close<br />

Feature<br />

22 Urban foxes<br />

Opinion<br />

24 Light pollution<br />

25 An Exeter SWAN<br />

News & Reviews<br />

26 News & events<br />

Want more <strong>Life</strong> over the christmas<br />

break? Keep up to date with the latest in<br />

nature...<br />

facebook.com/pages/<br />

<strong>Life</strong>-<strong>Nature</strong>-<strong>Magazine</strong><br />

Careers<br />

28 Careers & volunteering<br />

<br />

30 Mammal tracks ID<br />

twitter.com/<strong>Life</strong><strong>Nature</strong>Mag<br />

Also keep an eye out for our new website<br />

www.lifenaturemagazine.co.uk ...coming soon!<br />

3

Image of the Issue: Tim Hunt, www.timhuntphotography.co.uk

EXETER RESEARCH FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

Speedy snails<br />

shot to fame<br />

On a chilly night in May, in the walled<br />

garden at the Penryn campus, the<br />

temporal and spatial movements of<br />

garden snails were recorded by University<br />

of Exeter undergraduate researches, led<br />

by Assosiate Professor of Ecology Dave<br />

Hodgson. The study reached international<br />

fame and became a youtube sensation,<br />

thanks to the glowing garden snails that<br />

took part.<br />

The lungworm species Angiostrongylus<br />

vasorum, is a type of parasitic<br />

<br />

foxes. It causes illness in dogs and if left<br />

untreated, it can be fatal. It is suspected<br />

that the larvae are inadvertently ingested<br />

by canines through consumption of these<br />

unappetising gastropods from grass or<br />

on chew-toys; the lungworm life cycle<br />

completes when eggs are passed from the<br />

dog in fecal matter ready to be taken on<br />

by the intermediary garden hosts once<br />

again. The research commissioned by<br />

Bayer as part of their ‘Be Lungworm<br />

Aware’ campaign aimed to understand the<br />

distribution, movement and habits of snails<br />

within a typical garden environment in<br />

order to develop better protection for dogs<br />

from this now endemic problem.<br />

Over 450 snails were collected on the<br />

Penryn campus or within 30km of the<br />

surrounding area. They were numbered,<br />

then either marked with UV paint or<br />

<br />

their shell. Those from campus had their<br />

initial collection location GPS tagged to<br />

see if they were able to return ‘home’ at a<br />

later date. The snails were then released at<br />

dusk from one location and a professional<br />

<br />

<br />

time-lapse photography and a UV cannon.<br />

Measurements were taken every 30 minutes<br />

to determine the distance and direction<br />

of the snails movement, with further data<br />

collected over the ensuing hours and in<br />

the following weeks. The visual results<br />

were stunning; see the video on YouTube<br />

under ‘Lungworm snail experiment’. More<br />

interestingly, insights into their speed and<br />

distribution became apparent. With speed<br />

records for land-snails only previously<br />

found within the Guinness Book of<br />

World Records, the team discovered that<br />

snails move at a blistering pace… of<br />

approximately 32cm per hour, with top<br />

speeds of 100cm per hour. Okay, so it may<br />

not be blistering but it’s faster than it seems<br />

when watching these slippery invertebrates<br />

<br />

snail can easily cover the entire distance<br />

of the average UK garden in one night,<br />

<br />

mate, or seek refuge inside a pet’s beloved<br />

squeaky toy.<br />

After releasing the snails at dusk, they<br />

<br />

of the study and it was within this time<br />

frame that the greatest speeds were<br />

recorded. It’s possible that keeping the<br />

<br />

<br />

6

EXETER RESEARCH FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

be due to the onset of daylight hours<br />

stimulating the snails to retreat into their<br />

shells to avoid predation or dehydration<br />

and thereby slowing down in the morning.<br />

Interestingly, a small number of snails<br />

moved at much greater speeds than others<br />

and were more likely to create their own<br />

<br />

of other snails showed preference to<br />

crawling upon slime already laid down<br />

by another. Exploratory behaviour was<br />

noted across the group, pointing towards<br />

a preference for snails to hide at the base<br />

of trees, in long grass, or near to a water<br />

source – indicating that it is important to<br />

be aware of outside water sources that your<br />

dog drinks from, or long grasses that it<br />

explores. Snails were often seen to change<br />

direction often, meaning the average<br />

garden could harbour hundreds of possibly<br />

eliminating all snails from your garden,<br />

but be aware of what your dog is picking<br />

up, and check their toys and bowls for any<br />

signs of snails. Clean these items often,<br />

and don’t leave them out overnight for<br />

inquisitive snails to hide underneath. Pick<br />

up your dog’s poo – if a dog is infected,<br />

you might not know it, and leaving poo<br />

can help the spread of the lungworm.<br />

Moving forward with the observations<br />

Images: First two from the left: Dan Blumgart, Right: Emma<br />

Simpson-Wells, Cut-out: Kieran Hollingsworth.<br />

Dr Hodgson’s favourite<br />

moments from the media<br />

frenzy include:<br />

1. Whilst being interviewed on BBC<br />

Breakfast being asked by a viewer<br />

whether snail slime was hallucinogenic<br />

and whether she should take her snaillicking<br />

daughter to hospital.<br />

2. Seeing a German newspaper with<br />

the headline “Schnelle Schnecken!”<br />

3. Earning a Drivetime car sticker from<br />

Simon Mayo’s Radio 2 show.<br />

infected snails. Very few snails<br />

‘returned home’, not being<br />

recorded back at their initial<br />

collection site. A lack of<br />

returning snails may not put<br />

paid to the homing instinct<br />

<br />

were encountered relocating<br />

snails in daylight and rapidly<br />

growing foliage.<br />

The study went viral and<br />

appeared in 32 UK national<br />

newspapers and magazines,<br />

155 national and international<br />

TV and radio stations, 276<br />

news websites, reaching global<br />

audiences in the millions; the<br />

last count on YouTube showed<br />

more than 43,500 hits!<br />

We aren’t advocating<br />

made so far, Dr. Hodgson hopes to look<br />

into the re-use of slime trails by snails to<br />

minimise energy costs, and to look into the<br />

<br />

the mucus itself. Watch this space. Slowly.<br />

Written by Linday Leyden, Alumnus<br />

at The University of Exeter, Cornwall<br />

Campus.<br />

7

CAREERS THE WEIRD & WONDERFUL SUMMER ISSUE<br />

Images: Pond dipping, Kevin Murphy; Kieth Leeves, http://www.cornwallwhaleanddolphinwatching.co.uk<br />

28

NEW IN SCIENCE FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

Magnetic eyes and iron beaks:<br />

<br />

Image: Lauren Stevens, 2013; Diagrams: Georgia Cass, 2013.<br />

Finding your way in the dark is always a challenge. Whether you’re a bat<br />

catching insects in a dense tropical rainforest, or a badger digging your sett<br />

in an English woodland, sensitivity in darkness is essential to your survival.<br />

Exploitation of the darkest hours has led<br />

to a huge range of adaptations designed<br />

to increase an animal’s ability to<br />

navigate at night. Purely nocturnal creatures<br />

tend to sport more obvious adaptations to<br />

living in darkness; the giant eyes of the bush<br />

baby are a prime example. However, for<br />

those who need to be active night and day,<br />

migrating birds for example, the transition<br />

can be tricky.<br />

Initial research suggested that birds, such as<br />

homing pigeons, use landmarks imprinted<br />

<br />

Other birds like European robins are known<br />

to use a combination of landmarks and the<br />

position of the sun and stars as a guide.<br />

Recent studies have had some fascinating<br />

insights into how birds on the wing navigate<br />

at night. It has now been suggested that<br />

the retinas in the eyes of migratory birds<br />

are in fact able to not only detect light, but<br />

<br />

<br />

wintering and breeding grounds. Such an<br />

anatomical feature requires incredible levels<br />

of sensitivity and detection of light at low<br />

levels, and unfortunately, doesn’t come with<br />

a simple explanation. How can the retina<br />

detect the magnetic pull of the earth? Two<br />

main theories have developed.<br />

Light-dependent navigation<br />

One such theory involves blue-light-sensitive<br />

photoproteins known as cryptochromes.<br />

Some scientists believe these molecules to be<br />

key in the detection of the earth’s magnetic<br />

<br />

magnetoreceptors at a bird’s disposal. The<br />

cryptochromes, of which birds are known<br />

<br />

send the information along ganglion nerve<br />

cells to the brain, where it can be processed<br />

into directional information that the bird can<br />

respond to. These ganglion cells have been<br />

found to be particularly active in migratory<br />

birds such as garden warblers and European<br />

robins when tested under moonlightstrength<br />

white light. Although this ‘compass’<br />

is dependent on the presence of light, it is<br />

extremely sensitive and has been found to<br />

function at light intensities equivalent to<br />

that of a ‘partly clouded moonless night’.<br />

Impressive, when you consider your<br />

<br />

unfamiliar, lightless expanses.<br />

In addition, an area in the front of the brain,<br />

known as ‘Cluster-N’ has been shown to<br />

be highly active when birds are orientating<br />

through night-time migration. The lightdependent<br />

information is transmitted from<br />

the retina in the eye to Cluster-N, which<br />

is activated under low light intensities.<br />

Studies on European robins have shown<br />

that deactivation of this cluster renders their<br />

magnetic compass useless.<br />

Magnetite-based navigation<br />

Another theory on the ability of migratory<br />

birds to navigate at night involves iron<br />

deposits, found in the upper beak of several<br />

bird species. The migration distance of these<br />

birds range widely from year-round residents<br />

such as pigeons, to long-distance transequatorial<br />

migrants like garden warblers, and<br />

it is therefore thought that iron deposits will<br />

occur in most bird species.<br />

The iron-rich mineral structures were<br />

initially thought to act literally as magnets,<br />

with the metal aligning with the magnetic<br />

pull of the earth. This information was<br />

thought to then be relayed to the brain<br />

by the trigeminal nerve; a primary nerve<br />

connecting the face and brain. Despite<br />

this, experiments severing the trigeminal<br />

nerve found that the birds’ sense of<br />

<br />

recent experiments have severed the nerve<br />

and subsequently relocated the birds up<br />

to 1000km east of their original starting<br />

point. This study showed that cutting the<br />

<br />

their sense of location; birds would continue<br />

as if they had never been moved, and end<br />

up lost, rather than readjusting their course.<br />

It seems therefore that the iron-deposits<br />

<br />

‘compass sense’ - sense of direction, of a bird,<br />

<br />

their sense of location.<br />

Neither of these theories provides a complete<br />

explanation of how birds navigate at night.<br />

As with many aspects of biology, it is likely<br />

that no one theory can explain all of the<br />

variation in the adaptations that we see.<br />

Essentially it seems probable that both<br />

the light-dependent and magnetite-based<br />

theories work together; depending on the<br />

light available both mechanisms will work<br />

to send directional information to the brain,<br />

with the iron-based clusters only activated at<br />

low light intensities.<br />

The avian eye and<br />

the magnet effect<br />

Directional information provided by<br />

<br />

the bird’s eye by chryptochromes. It is<br />

thought that light absorption generates<br />

radical pairs within chryptochromes<br />

in the retina which are determined by<br />

molecule orientation in relation to the<br />

<br />

iris<br />

lens<br />

cornea<br />

The earth’s<br />

<br />

gives migrating<br />

birds their sense<br />

of direction, or<br />

‘compass sense’.<br />

N<br />

retina<br />

optic nerve<br />

So next time you’re following your Sat-Nav<br />

in the dark, or wandering home from the<br />

pub late at night, spare a thought for these<br />

<br />

miles a year whilst using nothing but their<br />

fantastically clever, built-in GPS.<br />

Georgia Cass, Alumnus of<br />

the University of Exeter,<br />

Cornwall Campus<br />

9

NEW IN SCIENCE FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

Image: Kostya Pazyuk<br />

Swiftly rising at<br />

dusk and dawn<br />

Common swifts (Apus apus) rarely settle on the ground. So rarely, that<br />

their family was named ‘apodidae’, from the ancient Greek ‘without feet’.<br />

<br />

are rapid and constant. It is therefore vital for their survival to gather as<br />

<br />

Without Google maps and the weather forecast on your smart phone,<br />

how would you understand the day ahead?<br />

You’ve probably seen swifts darting<br />

around our summer skies and<br />

heard their loud screaming calls in<br />

the evenings and early mornings, these<br />

elements are all generally part of social<br />

<br />

that towards the end of these nighttime<br />

‘screaming parties’, swifts climb<br />

<br />

originally assumed the ascent was to locate<br />

<br />

sleep, but developments show that swifts<br />

do not appear to select optimal wind-<br />

<br />

Additionally, a secondary, identical ascent<br />

has been discovered at dawn, when they<br />

<br />

An ascent at dusk to<br />

locate optimal sleeping<br />

altitudes now seems<br />

unlikely; an identical<br />

ascent happens again<br />

at dawn.<br />

So what is this costly climb all about?<br />

<br />

would you do to get a better look at where<br />

you are? Climbing a tree would give<br />

<br />

true of swifts? Adriaan Dokter and his<br />

team decided it was time to answer these<br />

<br />

Doppler weather radars are typically used<br />

to measure the movements and intensity<br />

<br />

birds leave characteristic signatures from<br />

<br />

allowed Dokter to investigate the timing<br />

<br />

altitudes in order to uncover the purpose<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

at twilight, isochronally from sunset and<br />

<br />

According to Google, twilight is a cult<br />

vampire-romance novel, but in its original<br />

context it’s a rather unique and useful<br />

<br />

no longer visible in the sky at dusk, or<br />

just before it becomes visible at dawn,<br />

sunlight still scatters through the upper<br />

atmosphere, illuminating the lower for a<br />

<br />

of illumination provides crucial cues for a<br />

<br />

cover, the nocturnal to start foraging and<br />

even for zooplankton to alter their position<br />

in the water column to account for<br />

<br />

however, hold potential for more than an<br />

<br />

landscape features, light polarization and<br />

stars makes it an information rich period<br />

of time, with the visual cues of both day<br />

<br />

Unable to link the height of the ascent to<br />

environmental parameters, Dokter suggests<br />

that these ascents are akin to looking up<br />

the weather forecast online before deciding<br />

<br />

create their very own weather forecast and<br />

map linked to distant landmarks, helping<br />

them to locate suitable areas for foraging<br />

or sleeping and to navigate within them<br />

<br />

to accurately assess weather conditions<br />

where you are currently and where you<br />

will be in the next few hours is clearly<br />

very useful when relying heavily on a diet<br />

<br />

When whizzing around as swiftly as<br />

a swift, building a picture of the best<br />

directions prevents them from travelling<br />

<br />

needs just two trips to higher altitudes<br />

to get a good look around, leaving more<br />

<br />

Swifts can create their<br />

very own weather<br />

forecast linked to distant<br />

landmarks, helping them<br />

to locate suitable areas<br />

for foraging.<br />

<br />

navigate when their sight is hindered by<br />

darkness, and you may remember the<br />

dung beetle’s nighttime escapades using<br />

the milky-way as a compass from the<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

with discoveries like these pushing the<br />

boundaries of animal senses beyond our<br />

<br />

Dokter and his team have plans to more<br />

closely link individual behaviour with<br />

the daily variation in visibility in order to<br />

better understand the vertical movement<br />

<br />

Emma Simpson-Wells,<br />

Alumnus of the University of<br />

Exeter, Cornwall Campus.

Moths:<br />

by Laura Richardson

White ermine (Diaphora mendica) – This moth was found during<br />

one of EcoSocs Moth Monitoring mornings and was a highlight<br />

for all. One of the most glamorous looking of all the moths, it is<br />

as if it is wearing Cruella Deville’s coat. During the early hours of<br />

the morning moths are docile creatures and are only fully active<br />

once they are warmed. They achieve this quickly by shivering

◀<br />

Peach blossom<br />

(Thyatira batis)<br />

– Peach blossoms<br />

are easily one of our<br />

most attractive moth<br />

species because of<br />

their wonderful pink<br />

blotches. This individual<br />

(along with the Puss<br />

moth pictured below)<br />

was found during the<br />

Bioblitz that took place<br />

on Tremough campus<br />

and at Argal and College<br />

Reservoirs in June.<br />

Collecting them from<br />

the traps was a mad<br />

rush that morning; as<br />

the heavens opened<br />

and the thunder and<br />

lightning commenced,<br />

it felt more like a rescue<br />

mission! I’m happy to<br />

report there were no<br />

casualties.<br />

◀<br />

Poplar hawkmoth (Laothoe populi) - When opening a moth<br />

trap or over turning an egg box (which are placed in the traps<br />

to give the moths something to rest on and shelter in) you never<br />

<br />

be beautiful, and sometimes they can be gigantic! With a 70mm<br />

wings span, poplar hawkmoths are one of the great gems of the<br />

moth trap treasure chest.<br />

Puss moth (Cerura vinula) – For this photograph I<br />

chose a low angle to put me on the same level as the<br />

moth and put two of its best features in the frame; puss moths<br />

have incredible, long, furry legs that stretch out in front of them<br />

when they rest on branches. The fur that covers them is what<br />

inspired their cat-like name. The second feature shown is the<br />

<br />

sometimes potential mates.<br />

◀

◀<br />

Peppered moth (Biston betularia) – This species is often used as an example of natural selection and also as a<br />

pollution indicator. In areas where pollution is high the bark of trees and walls are darker and so darker Peppered<br />

<br />

exposed to predators. This is the opposite in less polluted areas (such as Cornwall). As an areas air quality changes over<br />

time so does the colour of the local peppered moth population.<br />

◀

IN THE FIELD FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

Images: Clare Greenwood, 2013. Illustration: Chris Beirne, 2013.<br />

16<br />

Old timers:<br />

<br />

Chris Beirne<br />

I’m suddenly startled by a rasping bark<br />

ringing out across the wooded valley,<br />

in the semi-darkness of this warm<br />

summers evening. The call sounds like it<br />

might belong to a large and vicious predator<br />

and if you believed the local tales, you<br />

would know that a ‘big cat’ stalks this area<br />

of forest. Thankfully, my common sense<br />

intervenes. I am not in a wild and isolated<br />

fragment of the Amazonian rainforest but<br />

sat on a fallen beech tree just three and a half<br />

kilometres from the M5 in Woodchester<br />

Park, Gloucestershire, and the vicious<br />

caller is in fact, a roe deer. I am trying to<br />

catch a glimpse of the notorious nocturnal<br />

mammal that is present here in abundance<br />

- the European badger. Badgers live<br />

in large underground networks<br />

of tunnels called setts; in<br />

this location and many<br />

others in the<br />

south of<br />

England, they live communally with other<br />

badgers in social groups. As the barking roe<br />

deer moves away all is quiet and my mind<br />

begins to wander again.<br />

I have been studying badgers for the last<br />

two years in order to understand the aging<br />

process. On the surface of it, that sounds<br />

pretty strange. Why would you study badgers<br />

in order to understand how things age?<br />

First and foremost, humans are far too long<br />

lived to collect data on during the timescale<br />

of a normal PhD (3 to 4 years), so I would<br />

be looking at less than 5% of an individual’s<br />

lifespan. Secondly, most of what we have<br />

learnt about ageing comes from laboratory<br />

strains of rats and mice. Such organisms are<br />

highly inbred to ensure that each individual<br />

is as genetically identical to each other as<br />

possible and they are reared in exactly the<br />

<br />

experiments are repeatable. However, it’s<br />

the variation in ageing rates that make it<br />

<br />

all, everyone gets old, but why do some<br />

people get old faster than others? Working<br />

on a wild population of mammals - such as<br />

badgers - embraces the variation that might<br />

be important in determining how long an<br />

individual lives and how fast it ages.<br />

Everyone gets old, but why do some people get old faster<br />

than others? Working on a wild population of mammals<br />

- such as badgers - embraces the variation that might be<br />

important in determining how long an individual lives<br />

As badgers have a highly tuned sense of<br />

smell I have positioned myself downwind<br />

from one of the larger setts within the aptly<br />

named ‘Beech social group’. After such a<br />

warm summer, the leaf litter is tinder dry,<br />

so if there are badgers on the move I should<br />

hear them well before I see them. Sure<br />

<br />

to hear the rustling of leaves further up the<br />

<br />

one badger up there, there’s a whole group<br />

of them! Despite the proximity of the noise,<br />

the darkness leaves me sightless.<br />

The Food and Environment Research<br />

Agency (FERA) have been trapping the<br />

badgers in and around Woodchester Park<br />

for over thirty seven years in order to<br />

understand how bovine tuberculosis (bTB),<br />

a disease particularly damaging to the<br />

cattle farming industry, spreads between<br />

groups of badgers under natural conditions.<br />

<br />

given a unique tattoo in order to identify<br />

each individual and on each subsequent<br />

occasion the badger is caught, it is tested<br />

for bTB. I also take a small blood sample<br />

from each badger in order to take back<br />

to the University’s Molecular Genetics<br />

Lab and measure each badgers telomere<br />

length. A telomere is a region of repeating<br />

‘TTAGGG’ nucleotide sequence at the end<br />

of each chromosome which protects the<br />

vital gene coding regions of DNA from<br />

degradation. In humans, and some species<br />

of birds, telomeres are at their longest at<br />

birth then steadily reduce in length as they<br />

are eroded by cell division and the ‘wear<br />

and tear’ of everyday life. Telomere length<br />

is positively associated with the number<br />

of times a cell can divide, the longer they<br />

are the more times a cell can divide in<br />

culture. As such telomere length has been<br />

suggested to act as a molecular clock<br />

which determines your biological age.<br />

However most of the telomere research<br />

conducted to date has been performed on<br />

animals grown in controlled conditions. I<br />

<br />

important determinants of longevity<br />

in wild populations under natural<br />

conditions.<br />

Just as I am starting to lose all<br />

hope of spotting a badger, I hear<br />

a rustle to my left. A solitary<br />

badger ambles out of the darkness<br />

and takes me by surprise. It stops<br />

<br />

way and that, searching for<br />

earthworms. It is impossible to<br />

tell in the half light but I hope it is<br />

badger “L54” or his brother “L56”<br />

who have been captured every<br />

year here since they were born in<br />

the year 2000. I know for a fact<br />

they both have cataracts, and most<br />

likely arthritis to boot. Before my<br />

<br />

makes them live so long. Is it super<br />

long telomeres, good genes, or<br />

have they simply ridden out their<br />

luck for the last thirteen years?<br />

Suddenly the wind shifts and the badger<br />

stops in its tracks. As soon as it catches a<br />

<br />

<br />

from whence it came.<br />

Chris Beirne uses his<br />

knowledge of molecular<br />

techniques to understand<br />

the proccesses which cause<br />

the individual differences<br />

in ageing rates, working<br />

with the Centre for Ecology<br />

and Conservation at Exeter<br />

Cornwall Campus.

EVOLUTION FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

<br />

night sky:<br />

<br />

<br />

The discovery that bats use sonar – a process of producing sound and using the echoes bouncing back from objects to<br />

<br />

Illustrations: left: Aimee Jewitt Harris , right: Samuel Jay Chessel<br />

One of<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Theretra nessus<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

18

EVOLUTION FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

Bats have evolved many different adaptations, their skull shape determines their<br />

ability to produce sonar either orally or nasally.<br />

<br />

Jamaican fruit bat Artibeus<br />

jamaicensis (nasal sonar)<br />

Greater mouse eared bat<br />

Myotis myotis (oral sonar)<br />

The pressure for both bats and moths to be highly<br />

effective at their own game has escalated into an<br />

evolutionary arms race, with each party continually<br />

updating and fine-tuning their biological weapons.<br />

University, US, have recently<br />

<br />

<br />

against at least four species<br />

of Myotis spp. bats in their<br />

natural habitat in Arizona.<br />

Sonar jamming can give the<br />

moth those essential extra<br />

seconds it needs to escape and<br />

survive.<br />

The pressure for both bats and<br />

<br />

their own game has escalated<br />

into an evolutionary arms race,<br />

with each party continually<br />

<br />

biological weapons. Hunting<br />

with sonar in bats has selected<br />

on moths to avoid predation<br />

<br />

bias in the ability to detect<br />

ultrasound. In turn, the evasive<br />

<br />

use of ultrasound against the<br />

<br />

tuning of sonar techniques<br />

in bats. The Palaearctic pond<br />

bat (Myotis dasycneme) can<br />

switch between the type of<br />

sonar that it uses, alternating<br />

the frequency and pitch of<br />

ultrasonic clicks in response<br />

to moth activity. It can also<br />

<br />

basic trawling along the water<br />

surface to a form of aerial<br />

hawking. Some bats even go<br />

into silent or ‘whispering’<br />

mode when making their<br />

<br />

sneak up on their target. With<br />

each escalation in biological<br />

weaponry, there must be a<br />

greater investment in energy,<br />

physiology and behaviour.<br />

Whether an evolutionary arms<br />

race between bats and moths<br />

will conclude with a winner or<br />

cycle continuously is hard to<br />

<br />

group of insects that make up<br />

insectivorous bats’ diets and<br />

there are many others that<br />

make far easier prey items. In<br />

the meantime, there is plenty<br />

of entertaining research to be<br />

done for curious and creative<br />

biologists eager to follow the<br />

game.<br />

organism to a hunting bat must surely go to<br />

the Tiger moth (Bertholdia trigona), which<br />

produces a series of ultrasonic clicks that<br />

serve to ‘jam’ the signals of hunting bats.<br />

This is an exceptionally tricky and precision<br />

piece of defence as the moth clicks must<br />

<br />

<br />

If successful, moths can disrupt the auditory<br />

<br />

the returning echoes and so ‘jam’ the<br />

sonar signal. Biologists from Wake Forest<br />

Written by Dr<br />

Michelle Taylor,<br />

Associate Research<br />

Fellow at the<br />

University of Exeter,<br />

Cornwall Campus.<br />

19

Asking<br />

for<br />

trouble<br />

In February this year a four-week<br />

old boy was taken to St Thomas’<br />

Hospital after a fox attack left him<br />

with a serious hand injury. Stories<br />

about how dangerous foxes are<br />

appeared in the papers almost<br />

<br />

Johnson went as far as to call them<br />

a “menace”, and understandably,<br />

<br />

really at fault?<br />

Images: Gemma Malenoir 2013<br />

An urban retreat<br />

<strong>Life</strong> in the big city can be tough, and I<br />

don’t just mean for us. Despite being one<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

such as coyotes, Eurasian badgers, raccoons<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

It has been suggested that Vulpes vulpes,<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

A happy home<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Food glorious food<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Urban foxes might<br />

dine on rodents,<br />

<br />

fruit, pets,<br />

<br />

or food<br />

<br />

in<br />

return<br />

for a<br />

<br />

of these<br />

<br />

creatures.<br />

Up to<br />

60% of an<br />

<br />

<br />

The Telegraph has<br />

only managed to find<br />

five UK fox attacks<br />

within the last 11<br />

years, none of which<br />

were fatal.<br />

20

FEATURE FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

be made up of anthropogenic food. The<br />

availability of these food sources all year<br />

round makes it worth the risk of city living.<br />

Are we asking for it?<br />

<br />

since 2010, where two 9-month old girls<br />

received arm and facial wounds. In fact,<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

would go for the neck, not the hand, arm<br />

<br />

comparison to the number of dog attacks,<br />

animals most of us would consider a part<br />

of the family. It is understandable that the<br />

victims’ families are upset, but can we really<br />

<br />

<br />

only 13 - 14% living in urban areas.<br />

After the latest attack, the victim’s parents<br />

<br />

by several politicians. However, wildlife<br />

<br />

<br />

considered that humans are not the only<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Human conduct could be partly to<br />

blame for such attacks. Many households<br />

purposefully leave out food for their garden<br />

visitors, or try to entice them to eat from<br />

the hand. The availability of food so close<br />

to human dwelling is a tasty prospect for<br />

those brave enough to risk close encounters,<br />

but there is a wealth of food available to<br />

them in the urban environment, without<br />

residents providing additional sources. If the<br />

animals become habituated to our presence,<br />

they will no longer feel the need to keep<br />

<br />

could reduce the risk of confrontation.<br />

<br />

<br />

metropolises approach upon their<br />

territories without stopping to consider the<br />

consequences. Our cities don’t stop growing<br />

and when faced with the prospect of die or<br />

adapt, we must surely realise that animals<br />

that can adapt, will.<br />

Written by Jennifer Weller,<br />

second year zoology student<br />

at the University of Exeter,<br />

Cornwall Campus.<br />

21

EXPERIENCE FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

Eagle of<br />

the night<br />

The unexpected roughness of a branch grazing my cheek was a reminder<br />

that I should have worn my glasses. I’m short sighted and when the light<br />

fades it makes it even harder to differentiate between upcoming objects<br />

and simple darkness. We followed on behind Pete, the most surprising<br />

birder I have come across so far.<br />

Image: Marcus Hoare (taken at the New Forest falconry display).<br />

It was only a few days previously, sitting<br />

around a very French farm house table<br />

in the very French farm hamlet that<br />

my family has been visiting since I was<br />

9 months old, that I noticed a tattoo of a<br />

barn swallow on his chunky forearm. “I<br />

don’t think you want to know”, he said<br />

in his very-unfrench-Essex-accent when I<br />

asked him what inspired it. He eventually<br />

relinquished the tale of how, as a young<br />

man, he used to shoot birds to pass the<br />

<br />

his boat. He ended up shooting so many<br />

that he came to feel sorry for the feathered<br />

creatures, and decided to spend the rest of<br />

his life learning as much as he could about<br />

them as a sort of penance.<br />

It was this conversation in which we learnt<br />

that there were Eurasian eagle owls nearby<br />

and that Pete had heard them calling whilst<br />

sitting quietly, waiting for a catch on his<br />

<br />

got really excited and I, unknowing,<br />

was a little confused. A plan was hatched<br />

nonetheless and a few nights later we were<br />

winding our way down to the Dordogne<br />

River in a red and white VW camper, part<br />

of the family since 1987, in pursuit of a<br />

sighting of this elusive eagle owl.<br />

As we followed Pete, he told us what they<br />

sounded like, and we all had a go at an<br />

impersonation, resulting in unsurprisingly<br />

poor attempts to mimic something<br />

unknown. When we reached the water’s<br />

edge we sat uncomfortably on precariously<br />

balanced rocks, and looked to the other<br />

side of the steep, tree lined ravine. We<br />

had binoculars, but as time went on we<br />

started to lose faith in our search, the trees<br />

were dense and where there were patches<br />

of open rock, the sheer width of the<br />

Dordogne made them too far away to pick<br />

<br />

eagle owl sitting amongst the crevices.<br />

The grey-blue hues of dusk turned to<br />

black, and now my eyesight was only as<br />

useless as everybody else’s. We sat talking<br />

in whispers, and joked to each other in<br />

hushed tones that we should try and call<br />

it out of the trees. I let out my best eagle<br />

owl impersonation, blowing through top<br />

teeth pushed against bottom lip, sounding<br />

something a bit like a mournful kazoo.<br />

<br />

then through the quiet came a distant “oh<br />

huu” and we all gasped and fell into hushed<br />

giggles. I could barely believe it and<br />

thought it a coincidence, so I repeated my<br />

kazoo call and sure enough; “oh huu” came<br />

the owl’s reply.<br />

I continued my conversation with the<br />

eagle owl for a while, calling out into the<br />

darkness and listening with anticipation<br />

for its replies to resonate through the<br />

trees. The others tried too, but perhaps<br />

something about the frequency of my<br />

voice hit the right note with my new<br />

friend. I heard it move from the left side<br />

of the forest to the right, and up to the<br />

top of the steep sides of the ravine, but it<br />

<br />

we started talking about stories of how<br />

one owl can take down a sheep or a young<br />

roe deer on their own, and I imagined the<br />

moment of such a giant animal swooping<br />

towards you, talons outstretched. I don’t<br />

feel shame in fearing them; it’s a form of<br />

respect that we can recognise when to keep<br />

our distance. As time went on its replies<br />

got shorter and sharper, it seemed annoyed,<br />

that I, another owl, was in its territory<br />

uninvited and communicating with it out<br />

of turn. I drew our conversation to a close.<br />

Our feet were cold and the hours left to<br />

pack up to return home were dwindling,<br />

so we got up, and with one last hooting<br />

goodbye, we scrambled our way back to<br />

the van.<br />

Written by Roz Evans, 3rd<br />

year Conservation Biology<br />

and Ecology student with the<br />

University of Exeter, Cornwall<br />

Campus.

OPINION FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

The fading night<br />

Some years ago, while hitchhiking around the sparsely populated landscape of Namibia, I was camping in a remote location in<br />

the north of the country. There was no moon that night, and leaving my tent to go to the toilet I was initially overwhelmed by the<br />

incredible display of stars arching overhead, but also by a deep fear. It was so dark, with barely any discernable background glow on<br />

the sky, that the only way to see where the horizon began was by the absence of stars. This was the deepest view of creation I’d ever<br />

had, and yet it felt more claustrophobic than ever, as though the universe was on the verge of collapsing on itself. It was a profound<br />

reminder of how adapted I am to the day, and how successfully we have banished the darkness of night from our experience in the<br />

developed world.<br />

Our remote ancestors in the Mesozoic<br />

were well adapted to nocturnal life,<br />

as many mammals and other animals<br />

are today. The daily cycle of light and dark<br />

are essential in regulating the circadian 24-<br />

hour rhythms of most animals. Humans have<br />

<br />

millennia, but over the past century there has<br />

been an explosion of night illumination with<br />

the advent of electric lighting.<br />

<br />

the most overlooked factor in the complex<br />

web of the causes of biodiversity decline.<br />

<br />

to a reduction in visibility to predators. In a<br />

natural environment these moonless nights<br />

will be exploitable with each lunar cycle,<br />

<br />

opportunities are lost. It’s apparent that<br />

<br />

species in the shadows.<br />

A brief look at a satellite image of the world<br />

at night shows how seriously our densely<br />

<br />

has seen serious declines in numerous animal<br />

populations over the last few decades. Moths<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

last decade, and we are just beginning to<br />

understand the extent to which the problem<br />

<br />

factors, particularly habitat destruction,<br />

<br />

in most population declines, but this is<br />

something that would be so easy to address.<br />

Aside from the obvious issue of wasted<br />

energy, do we really need streetlights to be on<br />

all night, especially on weeknights in rural<br />

villages? It’s comforting for us, and it has<br />

been argued that accidents and crime rates<br />

are lower in areas that are brightly lit, but<br />

Image: NASA, 2013.<br />

of many animals, and there is evidence that<br />

they disrupt the rhythms of birds, insects,<br />

reptiles and numerous other nocturnal<br />

animals. One of the best-studied examples is<br />

that of turtle hatchlings on tropical beaches,<br />

<br />

horizon inland. Under normal circumstances,<br />

hatchlings instinctively orientate away from<br />

the dark silhouette of the horizon towards<br />

the brighter, starry sky, leading them to the<br />

<br />

electric lights, the turtles often head inland,<br />

away from the sea, where they can become<br />

exhausted and disorientated, run over by<br />

<br />

the extra illumination to their advantage.<br />

Light pollution has been linked to population<br />

declines in snakes, disruptions of migrating<br />

birds and bats, amphibians, and invertebrates.<br />

Research suggests that invertebrate activity<br />

and small mammal distribution is increased<br />

on darker, moonless nights, probably due<br />

lights being brighter than stars even at large<br />

distances, the insects become disorientated<br />

and unable to navigate in the darker areas<br />

<br />

night of moths around streetlamps saps the<br />

animals’ energy, and creates an aggregation<br />

of prey for nocturnal insectivorous predators<br />

such as bats, which in turn are more<br />

<br />

accidents. Moths escaping predation will often<br />

land nearby, unable to navigate in the dark<br />

surroundings, leading to a loss of opportunity<br />

for feeding. This process has been referred<br />

<br />

insects are drawn out of suitable habitats<br />

for miles around the light source, leading<br />

to depleted populations in the surrounding<br />

countryside.<br />

The reduction in moth populations may<br />

also be a major factor in the current serious<br />

<br />

are heavily dependent on moths as prey.<br />

we need to spend more energy and money<br />

understanding which lighting types have the<br />

least ecological damage. Thankfully some<br />

local authorities are rolling out testing periods<br />

reducing the amount or type of lighting used,<br />

but this is largely focused on money saving<br />

rather than ecosystem regenerating.<br />

<br />

quietest periods each night would give<br />

wildlife a chance to disperse and resume<br />

it’s normal rhythms of activity, and we<br />

<br />

consumption, enjoying richer biodiversity,<br />

and of course, re-acquainting ourselves with<br />

the darkness which is as much a part of our<br />

circadian rhythm as any other species.<br />

Written by Feargus Cooney,<br />

third year Conservation Biology<br />

and Ecology BSc with the<br />

University of Exeter, Cornwall<br />

Campus.University of Exeter,<br />

24

WOMEN IN SCIENCE FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

Protecting our<br />

future SWANs<br />

As I write, the new undergraduate<br />

students are arriving, ready to embark<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Morgenroth also showed that even at<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Zeya Wagner and Liselle-Fae Jackson<br />

performing PCR technique in<br />

Tremough teaching lab<br />

Acronym Buster:<br />

CEMPS<br />

<br />

CLES<br />

<br />

STEM<br />

Engineering and Maths<br />

SWAN<br />

<br />

Get involved...<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

gender? Do you have any ideas<br />

<br />

undergraduate students gain<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Image: Laura Reddish, 2013.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

my head.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

they even graduate.<br />

Athena SWAN in a<br />

nutshell...<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

and attitudes towards women and removing<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Claire Young,<br />

Student Engagement,<br />

Widening Participation<br />

and Internationalisation<br />

Coordinator at the University<br />

of Exeter.<br />

25

NEWS FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

Badger vaccine<br />

success in Cornwall<br />

A<br />

government-funded badger<br />

vaccination scheme worth £2<br />

million has been granted this month<br />

to prevent the spread of bovine tuberculosis<br />

in the Penwith area of west Cornwall.<br />

This has come as welcome news to nearly<br />

200,000 people who signed an anti-badger<br />

cull petition as well large numbers of<br />

researchers, activists and land owners who<br />

have, for many years, been advocates of<br />

a vaccine over the cull. It has also been<br />

somewhat of a surprise given the recent<br />

culls, ordered by DEFRA, that have begun<br />

in Somerset and Gloucestershire with<br />

another in Dorset planned for next year.<br />

Until recently the favoured course of action<br />

has been controversial culling of badgers<br />

in infected areas; despite extensive studies<br />

failing to show lasting or measurable<br />

<br />

<br />

TB concluded in 2007 that other than<br />

the systematic or virtual elimination<br />

of badgers over very extensive areas - a<br />

realistically impossible task - culling<br />

actually increases the spread of bTB. Once<br />

most badgers are removed from the cull<br />

area, a new territory is opened up that is<br />

exploited by badgers in surrounding areas.<br />

Immigrant badgers are infected from<br />

abandoned setts and surviving infected<br />

individuals increasing badger-badger and<br />

badger-cattle transmission rates. The lower<br />

badger density means that there is greater<br />

movement than before the cull and the<br />

original infection spreads to a larger area.<br />

As Simon King, President of the Wildlife<br />

Trusts, said in an interview on Newsnight<br />

in 2012, “Badgers are not the enemy<br />

here, bovine Tuberculosis is… The way<br />

of countering it is not to kill badgers,<br />

the way of countering it is to get rid of<br />

bTB through vaccination, both with<br />

the badgers and cattle.” Under current<br />

EU legislation, the vaccination of cattle<br />

against bTB is prohibited as a proportion<br />

of individuals treated with the BCG still<br />

test positive in TB diagnostic tests. This<br />

means they cannot be declared free of the<br />

disease for trading purposes. Although<br />

new diagnostic tests are being developed<br />

<br />

and vaccinated individuals, it is likely to<br />

be at least 10 years before any change in<br />

EU legislation will permit any these tests<br />

or any vaccination programmes to be<br />

implemented on cattle.<br />

The Feral Pigeon<br />

Project announces<br />

the launch of<br />

its new app for<br />

Android.<br />

Recently showcased on BBC2’s<br />

hugely popular Winterwatch<br />

show, Adam Rogers founded<br />

the Feral Pigeon Project<br />

with the hope of mapping<br />

the variation in feral pigeon<br />

plumage colours across the<br />

UK.<br />

Most feral animals are<br />

uniform in colour, yet feral<br />

pigeons come in a wide array<br />

of colours - this variation<br />

is thought to be key to this<br />

charismatic bird’s success. He<br />

is asking people to count the<br />

number of pigeons of various<br />

colours and to report them via<br />

the project’s website or with<br />

its new app.<br />

He said, “Pigeons may not be<br />

as glamorous as many of the<br />

exotic animals a person could<br />

choose to study but take the<br />

time to look beneath the<br />

feathers and they’re just as<br />

superbly adapted as any of the<br />

<br />

The Feral Pigeon Project has announced the launch of its new app fo<br />

Android TM<br />

Recently showcased on BBC2's hugely popular Winterwatch show, Adam Rogers founded<br />

the Feral Pigeon Project with the hope of mapping the variation in feral pigeon plumage<br />

colours across the UK.<br />

Image: Samuel Shrimpton 2013<br />

The treatment of the European badger<br />

(Meles meles) with regards to bovine<br />

tuberculosis (bTB) has long been a topic of<br />

great debate. For over 30 years it has been<br />

known that the badger may contract and<br />

carry the pathogen responsible for bTB,<br />

Mycobacterium bovis, with a subsequent<br />

enquiries instituted by the government<br />

showing transmission of the disease from<br />

cattle to badgers and, more worryingly for<br />

farmers, from badgers to cattle. The high<br />

level of their interaction with cattle makes<br />

the badger a key species in the eradication<br />

of bTB.<br />

<br />

it will need to be carried for at least the<br />

next 6 years at a cost of around £650 per<br />

badger. Not cheap, but with over 30,000<br />

cattle slaughtered throughout the UK in<br />

<br />

cost of bTB to the UK taxpayer in the next<br />

decade predicted to be over £1 billion, the<br />

vaccination programme could be worth it<br />

in the long run.<br />

Written by Will Priestley, Alumnus of the<br />

University of Exeter, Cornwall Campus.<br />

Most feral animals are uniform in colour, yet feral pigeons come in a wide array of colours -‐<br />

The project hopes to uncover<br />

or with its new app.<br />

how pigeons are adapting to<br />

<br />

adapted as any of the African big five."<br />

environment, as well as<br />

helping To download to the spark app visit: people’s<br />

this variation is thought to be key to this charismatic bird's success. He is asking people to<br />

count the number of pigeons of various colours and to report them via the project's website<br />

He said, "Pigeons may not be as glamorous as many of the exotic animals a person could<br />

choose to study but take the time to look beneath the feathers and they're just as superbly<br />

The project hopes to uncover how pigeons are adapting to the influence of our urban<br />

environment, as well as helping to spark people's interest in the natural world.<br />

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=uk.co.hiafi.feralpigeon&hl=en_GB<br />

or scan the following QR code:<br />

To download<br />

the app scan:<br />

www.feralpigeonproject.com<br />

www.feralpigeonproject.com<br />

26

REVIEWS FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

Hotspots of Cornwall<br />

recommended by the editors of <strong>Life</strong><br />

"Tehidy Country Park makes for a sun-dappled<br />

leafy-green haze of a day. Leasuirely follow the<br />

<br />

and fauna residing in the woodland. Keep an<br />

eye out for some natural wood carvings too! ”<br />

- Samuel Jay Chessel, Picture Editor<br />

"Hell’s Mouth is a<br />

beautiful coastal<br />

spot for bird<br />

watching. Fulmars,<br />

razorbills, guillemots<br />

and cormorants<br />

all nest there, and<br />

gannets can be seen<br />

out to sea. Lie on<br />

the grassy cliff and<br />

watch them swoop<br />

around below you! ”<br />

Illustration: Emma Simpson-Wells 2013. Images: chough: Dave Jones, guillemot & tree canopy: Emma Simpson-Wells, bluebells: Roz Evans, dipper: Billy Heaney<br />

- Emma Simpson-<br />

Wells, Creative<br />

Director<br />

“The Lizard, most southerly<br />

point, is amazing in winter<br />

storms but beautiful in the<br />

summer. The wildlife there<br />

is unique and you’re pretty<br />

much guaranteed something<br />

each time you visit!”<br />

- Charli Sams, Picture Editor<br />

"Kennall Vale <strong>Nature</strong><br />

Reserve is a great little<br />

woodland hideaway.<br />

Slightly inland, and with<br />

a big stream running<br />

through there’s<br />

<br />

from dippers, to<br />

woodland anemones<br />

and an impressive<br />

range of fungi!"<br />

-Georgia Cass, Sub-<br />

Creative Director<br />

"I'm a bit in love<br />

with Enys gardens<br />

at the moment.<br />

Although it isn't<br />

wild, it's just<br />

stunning when<br />

you go in bluebell<br />

season, so keep<br />

it on your list as<br />

something to look<br />

forward to until<br />

spring. The whole<br />

place is really well<br />

managed for wildlife<br />

with ponds and<br />

a huge variety of<br />

vegetation. Students<br />

get in for £2 and<br />

there's a tea room<br />

to top it all off!”<br />

- Roz Evans, Editor<br />

in Chief<br />

27

CAREERS FROM DAWN UNTIL DUSK AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

Claire Young: Careers<br />

Interview<br />

BSc Conservation Biology<br />

and Ecology<br />

I have the longest job title<br />

EVER. Such a mouthful: Student<br />

Engagement, Widening Participation and<br />

Internationalisation Coordinator for CLES<br />

Cornwall at the University of Exeter. And<br />

people still don’t know what it means after<br />

I’ve said it!<br />

My job is so varied. Part of<br />

it involves working with current students<br />

to get them engaged in projects we’re<br />

running, as well as supporting them to set<br />

up their own. I also do a huge amount of<br />

outreach work with schools, developing<br />

lessons and teaching kids, trying to inspire<br />

them to get excited about science.<br />

Image Credit: Dave Jones<br />

Having autonomy in<br />

my job and being able to tailor it to my<br />

strengths and what I enjoy. I’m supposed<br />

to be an intern but I’m treated like an<br />

<br />

into the deep end and it has been very<br />

<br />

and I’ve achieved some great things.<br />

Having to convince<br />

people to come to events and take part in<br />

things that I’ve worked so hard on. At every<br />

event I’m always so worried no one will<br />

turn up! They usually do though!<br />

I was an engaged<br />

student myself and did lots of volunteering.<br />

I was also a Student Ambassador which<br />

gave me a lot of experience working with<br />

<br />

massively.<br />

I don’t really<br />

know! I’d love to do a PhD but I’m yet to<br />

<br />

me. I’m open to a most things but I need<br />

something that challenges me!<br />

Want to be part of <strong>Life</strong> <strong>Nature</strong><br />

<strong>Magazine</strong>?<br />

We are looking for a new team<br />

for a new year. So will be<br />

<br />

An Editor-in-chief<br />

Sub Editors<br />

Picture Editors<br />

Content Editors<br />

Layout Designers<br />

Either experienced or just keen<br />

to learn and put in the time!<br />

Must be pro-active!<br />

If you’re interested, e-mail<br />

life@exeter.ac.uk<br />

28

VOLUNTEERING FROM DAWN UNTIL DUSK AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

Sea Watch Foundation:<br />

New Quay<br />

Blue Reef Aquarium:<br />

Newquay<br />

Where & who?<br />

I am currently completing a seven week internship with Sea Watch<br />

Foundation in New Quay, Wales.<br />

Tasks and responsibilities<br />

Land surveys consisted of sitting on New Quay pier and counting the<br />

dolphins seen in the bay. The boat surveys involved recording cetaceans and<br />

the environment, such as sea state, and GPS coordinates. If dolphins were<br />

<br />

When groups of dolphins were spotted, behaviour forms were also<br />

used, along with the use of the hydrophone to record the dolphins<br />

<br />

through sightings and inputting data.<br />

Highlights<br />

I was able to hear the dolphins communicating through a variety of clicks<br />

and whistle through the hydrophone. This gave me an insight into the<br />

dolphin’s lives that not many people get.<br />

Lowlights<br />

I don’t really have a lowlight as I have never worked with marine mammals<br />

before. I was continuously learning not only about cetaceans, but also about<br />

the marine environment.<br />

Would you recommend it to others?<br />

<br />

to get involved with marine mammals.<br />

Where & who?<br />

I worked in Newquay’s Blue Reef Aquarium, with the<br />

volunteering being mainly run by Lee Charnock, one<br />

of the aquarium display team.<br />

Tasks and responsibilities<br />

My main tasks were to get the aquarium ready to<br />

receive visitors in the morning, which included soaping<br />

the octopus tank to keep it from fogging up with<br />

condensation. I would also run checks on the tanks<br />

including temperature and water quality. Feeding the<br />

<br />

main task, as well as going out to local rock pools and<br />

rivers to catch live food.<br />

Highlights<br />

It would have to be either feeding or playing with the<br />

octopus. Hand feeding cayman, logger head turtles<br />

and sharks was pretty cool, though having an octopus<br />

latching onto your arms is a pretty amazing feeling.<br />

Lowlights<br />

<br />

morning and having to clean the glass on over 50 tanks,<br />

especially the low glass, being 6 foot 5 tall.<br />

Would you recommend it to others?<br />

<br />

beach in Newquay, in the summer heat!<br />

Cost<br />

The only cost was petrol to and from where I was<br />

staying, so if you live close it would be all sweet.<br />

<br />

Yeah to a certain extent, helping the aquarium is always<br />

<br />

<br />

helped me in my exploitation of the sea module in 2nd<br />

year.<br />

Cost<br />

<br />

<br />

around New Quay.<br />

<br />

<br />

There have been many papers published from data volunteers helped to<br />

<br />

Do you think it will be helpful for your future career prospects?<br />

I believe it will. You learn so much, not only how to collect data out in the<br />

<br />

to input it onto databases. It also opens up opportunities to work in other<br />

<br />

Jess Cripps<br />

Do you think it will be helpful for your future<br />

career prospects?<br />

Well I’m now working in another aquarium closer to<br />

home after telling them about my Newquay experience<br />

in the summer, so it looks like it’s helping already!<br />

George Clayden<br />

29

ON YOUR DOORSTEP FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

Wildlife Watch<br />

October:<br />

Red Deer<br />

October is the peak of the red deer<br />

Cervus elaphus rut. Usually segregated,<br />

congregating into large single sex herds<br />

in open country, in the breeding season<br />

the stags return to the home rage of the<br />

hind deer creating large mixed groups.<br />

Males compete to win access to a group<br />

of females and by protecting their<br />

‘harem’, the dominant male will receive<br />

exclusive rights to mate with them.<br />

November:<br />

Thrushes<br />

By November visiting<br />

thrushes can be seen in large<br />

<br />

<br />

along hedgerows. Common<br />

migrants include redwing<br />

turdus iliacus<br />

turdus pilaris, most of the ones<br />

we see in Cornwall would<br />

have crossed the north sea,<br />

on passage from Scandinavia.<br />

They overwinter in the UK,<br />

departing in early spring.<br />

Redwings are easily spotted<br />

on the Tremough Campus, so<br />

keep your eyes peeled.<br />

Seals<br />

By November grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) colonies are bustling with their<br />

Phoca vitulina,<br />

pups much earlier in June-July. Grey seal pups moult their thick, white coat<br />

after three weeks, at this point their mothers will end their starvation period,<br />

leaving the pups to fend for themselves. Godrevy head in Hayle is a good<br />

place for seeing the new families interact.<br />

Image: red deer: Beth Arkwright, red wing, Hannah Walker;<br />

merveille du jour, Guy Freeman; seal pup, Liselle Fae Jackson;<br />

waxwing, Felix Smith; fungi, Charlotte Sams; moss, Claire Young.<br />

Moths<br />

<br />

moths, the Merveille du<br />

Jour Dichonia aprilina can<br />

be seen on the wing from<br />

late September to October.<br />

Although scarce, it is<br />

widespread, often occurring<br />

in woodland, hedgerows<br />

and gardens around the<br />

UK, in particular those<br />

with high numbers of oaks<br />

- their larval food plant. It<br />

is one of our most beautiful<br />

moths, especially when<br />

newly emerged.<br />

Fungi<br />

October is the month fungal<br />

diversity peaks, with the majority<br />

of the seasonal mushrooms<br />

fruiting. This is a great time<br />

to get into wild foraging as<br />

<br />

<br />

mushrooms emerge. But forage<br />

with caution; many poisonous<br />

species also thrive in October.<br />

These include the unmistakeable<br />

Amanita muscaria<br />

(pictured), as well as species<br />

which are confusingly similar to<br />

edible specimens; false chanterelle<br />

Hygrophoropis aurantiaca can<br />

cause some people serious harm<br />

and looks almost identical to<br />

other edible chanterelles.<br />

December:<br />

Moss<br />

In December when the<br />

temperatures drop really<br />

low, water everywhere<br />

can freeze, causing quite<br />

a spectacle in some<br />

places. Moss has a high<br />

water content, and lives<br />

in damp spots. The soft<br />

moss beds we are used<br />

to are transformed in<br />

to crunchy, icicle laden,<br />

glistening green walls.<br />

Waxwings<br />

During harsh winters, large<br />

<br />

Bombycilla garrulous are forced<br />

south, leaving northern and<br />

central Europe where they<br />

overwinter and visit the UK.<br />

They often make it as far south<br />

as Cornwall, and can be seen<br />

frequenting gardens and car<br />

parks in Falmouth, foraging on<br />

hawthorn Crategus monogyna<br />

and rowan Sorbus aucuparia<br />

berries.<br />

Written by Fraser Bell, MSc<br />

Applied Ecology Alumnus.

ON YOUR DOORSTEP FROM DUSK UNTIL DAWN AUTUMN ISSUE<br />

Illustration: Wynona Legg 2013<br />

Adaptations of a....<br />

<br />

<br />

to avoid detection by predators and insect prey.<br />

Nightjar<br />

<br />

retina enhances the nightjars’ vision<br />

at night by improving the light<br />

gathering ability of the eye.<br />

Big white patches on the ends of males’ wings<br />

<br />

territorial displays. Enthusiasts might take two<br />

handkerchiefs and wave them at arms length, to<br />

attract the attention of a territorial male.<br />

The beak is wider than it is long, opening<br />

widely in both directions providing a wide<br />

<br />

Their brown feathers create an illusion of a pile of<br />

leaves or a dead log, blending in perfectly with their<br />

<br />

for the times when they leave their nests.<br />

Image: Mozambique Nightjar, Jared Wilson-Aggarwal<br />

9

If you want to write for<br />

i f e<br />

n a t u r e m a g a z i n e<br />

The theme for the spring term’s issue is:<br />

Anthropogenesis...<br />

Just send us a short summary of your idea for an article or a<br />

photographic sequence to: life@exeter.ac.uk<br />

With thanks to our readers and supporters, The<br />

University of Exeter and University of Falmouth.<br />

Credit: Emma Simpson-Wells 2013