draft manuscript - Linguistics - University of California, Berkeley

draft manuscript - Linguistics - University of California, Berkeley

draft manuscript - Linguistics - University of California, Berkeley

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

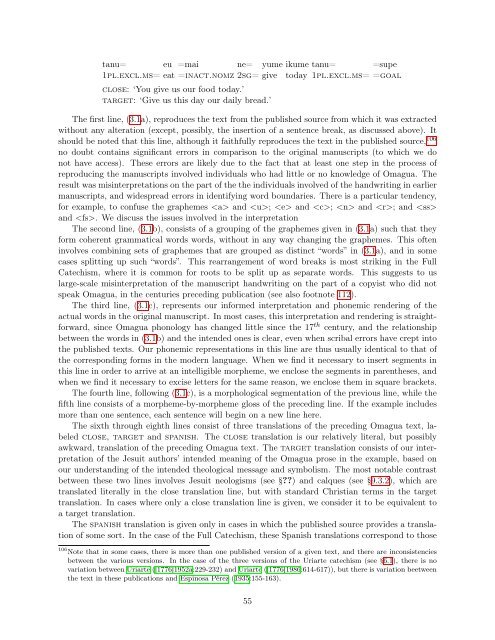

tanu= eu =mai ne= yume ikume tanu= =supe<br />

1pl.excl.ms= eat =inact.nomz 2sg= give today 1pl.excl.ms= =goal<br />

close: ‘You give us our food today.’<br />

target: ‘Give us this day our daily bread.’<br />

The first line, (3.1a), reproduces the text from the published source from which it was extracted<br />

without any alteration (except, possibly, the insertion <strong>of</strong> a sentence break, as discussed above). It<br />

should be noted that this line, although it faithfully reproduces the text in the published source, 106<br />

no doubt contains significant errors in comparison to the original <strong>manuscript</strong>s (to which we do<br />

not have access). These errors are likely due to the fact that at least one step in the process <strong>of</strong><br />

reproducing the <strong>manuscript</strong>s involved individuals who had little or no knowledge <strong>of</strong> Omagua. The<br />

result was misinterpretations on the part <strong>of</strong> the the individuals involved <strong>of</strong> the handwriting in earlier<br />

<strong>manuscript</strong>s, and widespread errors in identifying word boundaries. There is a particular tendency,<br />

for example, to confuse the graphemes and ; and ; and ; and <br />

and . We discuss the issues involved in the interpretation<br />

The second line, (3.1b), consists <strong>of</strong> a grouping <strong>of</strong> the graphemes given in (3.1a) such that they<br />

form coherent grammatical words words, without in any way changing the graphemes. This <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

involves combining sets <strong>of</strong> graphemes that are grouped as distinct “words” in (3.1a), and in some<br />

cases splitting up such “words”. This rearrangement <strong>of</strong> word breaks is most striking in the Full<br />

Catechism, where it is common for roots to be split up as separate words. This suggests to us<br />

large-scale misinterpretation <strong>of</strong> the <strong>manuscript</strong> handwriting on the part <strong>of</strong> a copyist who did not<br />

speak Omagua, in the centuries preceding publication (see also footnote 112).<br />

The third line, (3.1c), represents our informed interpretation and phonemic rendering <strong>of</strong> the<br />

actual words in the original <strong>manuscript</strong>. In most cases, this interpretation and rendering is straightforward,<br />

since Omagua phonology has changed little since the 17 th century, and the relationship<br />

between the words in (3.1b) and the intended ones is clear, even when scribal errors have crept into<br />

the published texts. Our phonemic representations in this line are thus usually identical to that <strong>of</strong><br />

the corresponding forms in the modern language. When we find it necessary to insert segments in<br />

this line in order to arrive at an intelligible morpheme, we enclose the segments in parentheses, and<br />

when we find it necessary to excise letters for the same reason, we enclose them in square brackets.<br />

The fourth line, following (3.1c), is a morphological segmentation <strong>of</strong> the previous line, while the<br />

fifth line consists <strong>of</strong> a morpheme-by-morpheme gloss <strong>of</strong> the preceding line. If the example includes<br />

more than one sentence, each sentence will begin on a new line here.<br />

The sixth through eighth lines consist <strong>of</strong> three translations <strong>of</strong> the preceding Omagua text, labeled<br />

close, target and spanish. The close translation is our relatively literal, but possibly<br />

awkward, translation <strong>of</strong> the preceding Omagua text. The target translation consists <strong>of</strong> our interpretation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Jesuit authors’ intended meaning <strong>of</strong> the Omagua prose in the example, based on<br />

our understanding <strong>of</strong> the intended theological message and symbolism. The most notable contrast<br />

between these two lines involves Jesuit neologisms (see §??) and calques (see §9.3.2), which are<br />

translated literally in the close translation line, but with standard Christian terms in the target<br />

translation. In cases where only a close translation line is given, we consider it to be equivalent to<br />

a target translation.<br />

The spanish translation is given only in cases in which the published source provides a translation<br />

<strong>of</strong> some sort. In the case <strong>of</strong> the Full Catechism, these Spanish translations correspond to those<br />

106 Note that in some cases, there is more than one published version <strong>of</strong> a given text, and there are inconsistencies<br />

between the various versions. In the case <strong>of</strong> the three versions <strong>of</strong> the Uriarte catechism (see §6.1), there is no<br />

variation between Uriarte ([1776]1952a:229-232) and Uriarte ([1776]1986:614-617)), but there is variation beetween<br />

the text in these publications and Espinosa Pérez (1935:155-163).<br />

55