Simon Keenlyside Malcolm Martineau - Barbican

Simon Keenlyside Malcolm Martineau - Barbican

Simon Keenlyside Malcolm Martineau - Barbican

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Simon</strong> <strong>Keenlyside</strong><br />

<strong>Malcolm</strong> <strong>Martineau</strong><br />

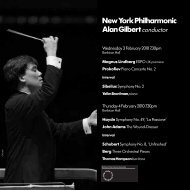

Wednesday 18 December 2013 7.30pm, Hall<br />

Uwe Arens<br />

Schoenberg<br />

Erwartung<br />

Eisler<br />

Spruch 1939<br />

Unter den grünen Pfefferbäumen<br />

In den Hügeln wird Gold gefunden<br />

Diese Stadt hat mich belehrt<br />

Zwei Lieder nach Worten von Pascal<br />

Erinnerung an Eichendorff und Schumann<br />

Verfehlte Liebe<br />

Spruch<br />

Britten<br />

Songs and Proverbs of William Blake<br />

interval 20 minutes<br />

Wolf<br />

Denk’ es, o Seele!<br />

Um Mitternacht<br />

Wie sollte ich heiter bleiben<br />

Auf eine Christblume II<br />

Blumengruss<br />

Lied eines Verliebten<br />

Schubert<br />

Alinde, D904<br />

Der Wanderer, D649<br />

Herbstlied, D502<br />

Verklärung, D59<br />

Brahms<br />

Verzagen, Op 72 No 4<br />

Über die Heide, Op 86 No 4<br />

Nachtigallen schwingen, Op 6 No 6<br />

<strong>Simon</strong> <strong>Keenlyside</strong> baritone<br />

Martin <strong>Martineau</strong> piano<br />

Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc<br />

during the performance. Taking photographs,<br />

capturing images or using recording devices during<br />

a performance is strictly prohibited.<br />

The City of London<br />

Corporation<br />

is the founder and<br />

principal funder of<br />

the <strong>Barbican</strong> Centre<br />

If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know<br />

during your visit. Additional feedback can be given<br />

online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods<br />

located around the foyers.

First the poetry, then the song<br />

Prima la musica e poi le parole, ‘First the music<br />

and then the words’, is the title of an 18thcentury<br />

libretto by Giambattista Casti, set to<br />

music by Antonio Salieri and, in the 1930s,<br />

the starting-point for Stefan Zweig when<br />

he began work on the libretto for Richard<br />

Strauss’s Capriccio. In Strauss’s case everyone<br />

knows that the phrase is ironic; the words may<br />

be the starting-point but it’s the music that<br />

matters. (Would anyone today willingly endure<br />

one of those long evenings when Richard<br />

Wagner read his latest ‘poem’ to a company<br />

of unswerving enthusiasts or an afternoon<br />

recitation of Piave’s libretto for La traviata?)<br />

However, when a composer turns his talents to<br />

Lieder, mélodies or songs, can we be as certain<br />

that it’s the music first and then the words? For<br />

one thing, with just a handful of exceptions,<br />

the poems that composers have chosen to<br />

set to music were written to stand alone. And<br />

for another it’s the writer who catches the<br />

imagination of the musician and suggests the<br />

music. Prima la poesia. Indeed, one of the<br />

pleasures of a recital such as this evening’s is to<br />

see where a writer/poet leads a musician. The<br />

art of the song would seem to be a genuine<br />

dialogue, rather than a struggle for artistic<br />

supremacy between the musician and the poet.<br />

That said, not all poets whose work is set to<br />

music are great, or even good poets. And<br />

while there are composers with tin ears when<br />

it comes to choosing poetry, they somehow<br />

sometimes polish dull metal into musical silver.<br />

That’s the miracle of Schubert’s Winterreise and<br />

of so many of Richard Strauss’s early songs.<br />

Arnold Schoenberg<br />

The text for Schoenberg’s Erwartung was<br />

written by a poet who spoke for and to a<br />

whole generation of German-speaking<br />

composers. Richard Strauss, Reger, Zemlinsky,<br />

Webern and Kurt Weill as well as Schoenberg<br />

all set Richard Dehmel’s words to music.<br />

His appeal was simple: he was radical in his<br />

politics, a champion of workers’ rights, and<br />

he was fiercely critical of the well-mannered<br />

hypocrisy about human sexuality that<br />

characterised late 19th-century German society.<br />

Love that dared to speak its name in all shapes<br />

and sizes was his principal song, the fulfilment<br />

of desires which encouraged men and women<br />

to unloose the artificial constraints of straitlaced<br />

bourgeois society. Dehmel was twice<br />

prosecuted for obscenity and blasphemy and his<br />

collection Weib und Welt (‘Woman and World’),<br />

published in 1896, was condemned to be burnt.<br />

Three years later Schoenberg set Erwartung<br />

from Weib und Welt to music, together with<br />

two other Dehmel poems; and we shouldn’t<br />

be surprised that the lush late Romantic style<br />

of these songs’ music seems to anticipate<br />

that of the wordless tone-poem Verklärte<br />

2

Nacht, since that string sextet took its cue from<br />

another of the poems in the same collection.<br />

Dehmel’s feelings for man and woman in<br />

nature and the excitement that attends erotic<br />

anticipation (Erwartung) are condensed into<br />

just 20 lines, with each of the five verses a<br />

chapter in the story of a lover waiting for a<br />

sign to enter the red villa by the sea-green<br />

pond. There’s something almost painterly,<br />

and Expressionist, in the poem’s eye for<br />

colour, while the varied rhyme-scheme<br />

only racks up the sexual excitement.<br />

Hanns Eisler<br />

Hanns Eisler studied with Schoenberg for four<br />

years in the early 1920s and was the first of the<br />

composer’s disciples to adopt serialism as a way<br />

of composing. But as a member of the German<br />

Communist Party Eisler was also encouraged to<br />

write music that would be readily understood<br />

by a popular audience. In Berlin by 1925, the<br />

composer embraced jazz and cabaret music<br />

and his music became increasingly political –<br />

to the evident dismay of his former teacher.<br />

Eisler also met Bertolt Brecht in Berlin,<br />

with whom he would collaborate for the<br />

rest of his life, in exile in the USA during<br />

the Second World War and then back in<br />

East Berlin, as it became after 1945.<br />

Unter den grünen Pfefferbäumen, Diese Stadt<br />

hat mich belehrt and In den Hügeln wird Gold<br />

gefunden are three of Brecht’s Hollywood<br />

Elegies, sardonic reflections on the City of the<br />

Angels, where ‘Paradise and hell-fire are the<br />

same city’, written when the poet/playwright and<br />

the composer were living in exile in Los Angeles.<br />

If Brecht’s pungent verse repays a debt<br />

to popular ballads the tone is entirely the<br />

playwright’s. In Spruch – Spruch meaning<br />

proverb – and Spruch 1939, there’s that<br />

knowingness about the ways of the world<br />

that fills the plays, particularly The Good<br />

Person of Szechwan. In den finsteren Zeiten is<br />

truly a proverb for the year that the Second<br />

World War in Europe began. ‘In the dark<br />

times will there also be singing? Yes, there<br />

will also be singing about the dark times.’<br />

Setting Brecht’s poetry may not have been that<br />

much of a choice for Hanns Eisler, joined as<br />

they were at the creative hip in Germany and<br />

then Hollywood, where both Eisler and Brecht<br />

worked on Fritz Lang’s movie Hangmen Also<br />

Die, for which Eisler was nominated for an<br />

Oscar in 1944, and then back in Berlin at the<br />

Berliner Ensemble. Yet there’s an unmistakably<br />

Brechtian tone to both of the passages that<br />

Eisler set from Pascal, Despite these miseries<br />

and The only thing. However, no one can fault<br />

this composer’s taste in setting Eichendorff’s<br />

fragment Erinnerung an Eichendorff und<br />

Schumann and Heine’s infinitely sad lyric about<br />

wasted love, Verfehlte Liebe. Here the composer<br />

is nothing if not his own man as he relishes a<br />

sense of mordant regret present in both writers.<br />

Benjamin Britten<br />

No 20th-century English composer sets<br />

words with more respect for their sounds<br />

and sense than Benjamin Britten. In Britten’s<br />

hands English is no longer die Sprache ohne<br />

Musik! Indeed, almost single-handedly he<br />

banishes that ancient canaille that language<br />

loses its musicality when set to music.<br />

One of the treats to be seen at a centenary<br />

exhibition this summer in the new Britten–Pears<br />

Archive in Aldeburgh was the composer’s copy<br />

of Robert Lowell’s translation of Racine’s tragedy<br />

Phèdre with the composer’s annotations on the<br />

page as he prepared the text that would become<br />

his late cantata Phaedra. An engagement with<br />

the text was clear, but there was also a sense<br />

of one artist inhabiting the words of another.<br />

So we should not be surprised that the shelves<br />

of the Red House where Britten and Peter Pears<br />

lived in Aldeburgh were packed with poetry<br />

3 Programme notes

ooks, reflecting this composer’s lifelong<br />

love for English poetry in particular. As early<br />

as 1935, when he was just into his twenties,<br />

Britten had made a setting of William Blake’s<br />

chilling account of unacknowledged rage in<br />

A Poison Tree, while his darkly erotic version<br />

of The Sick Rose is one of the most disturbing<br />

movements in that early masterpiece, the<br />

Serenade for tenor, horn and strings of 1943.<br />

Twenty years later Britten returned to William<br />

Blake when he began work on Songs and<br />

Proverbs of William Blake, in which settings of<br />

poems from Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of<br />

Experience are punctuated by epigrams from<br />

the undated Proverbs of Hell. Blake’s full title for<br />

the 1794 joint edition of the Songs provides us<br />

with a more than a hint of what these poems<br />

meant to the composer: Songs of Innocence<br />

and of Experience Showing the Two Contrary<br />

States of the Human Soul. We are divided<br />

against ourselves by ‘mind-forg’d manacles’ and<br />

constrained from personal fulfilment by custom<br />

and practice in a society where ‘Prisons are built<br />

with stones of Law [and] brothels with bricks of<br />

Religion’. Blake’s identification of innocence with<br />

childhood surely spoke to a composer whose<br />

abiding theme is the betrayal of innocence.<br />

At the heart – and literally so – of Songs and<br />

Proverbs of William Blake is one of the most<br />

compelling and mysterious of the poet’s lyrics,<br />

The Tyger. ‘What immortal hand or eye, Could<br />

frame thy fearful symmetry?’. How could a<br />

caring creator create the tiger and the lamb?<br />

For Blake, and perhaps Britten too, joy and<br />

terror co-exist in creation. And if the lamb in<br />

the poem conjures up a world of pastoral<br />

innocence, the tiger seems to have been forged<br />

in some divine industrial smithy. Yet next in this<br />

cycle of songs comes the proverb ‘The tygers of<br />

wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction’!<br />

Britten’s response to the ambiguities of Blake’s<br />

verse is to alternate a dislocating chromaticism<br />

with music that is tonally straightforward.<br />

Innocence and experience written into the score,<br />

words and music singing the same song.<br />

Hugo Wolf<br />

Hugo Wolf’s creative life was fast and furious. In<br />

just three years, from 1888 to1891, he composed<br />

over 200 songs that recreate the relationship<br />

between words and music to take account of<br />

the Wagnerian tonal revolution and thus renew<br />

the German Lieder tradition. These songs,<br />

with their carefully wrought introductions,<br />

extended postludes and shifting tonality are<br />

often music dramas in miniature. And their<br />

‘librettists’ can be numbered among the<br />

greatest German lyric poets of the 19th century:<br />

Eichendorff, Mörike and, above all, Goethe.<br />

Johann Wolfgang Goethe, prodigious in his<br />

literary achievements, attracted almost every<br />

serious Lieder composer from Schubert to the<br />

beginning of the last century. Goethe’s lyric<br />

poetry seems to distil the essence of German<br />

Humanism, blending a delight in the natural<br />

world with searching introspection; and always<br />

in an elegant but straightforward language<br />

that seems made for the composer. Indeed,<br />

Goethe himself observed that no lyric poem<br />

was really complete until it was set to music. ‘But<br />

then’, as he said, ‘something unique happens.’<br />

And so it does in Blumengruss, composed<br />

in December 1888, with Wolf building his<br />

song around a short but persistent theme<br />

that mirrors the lover who has stooped<br />

tausendmal – a thousand times – to gather<br />

flowers for a garland for the beloved which<br />

then he has clasped a hundred thousand<br />

times to his breast. And there’s more than a<br />

hint of resignation at the end, suggesting that<br />

this garland is all that he will get to hug.<br />

Wie sollte ich heiter bleiben comes from the last<br />

collection of poetry that Goethe worked on,<br />

the West-östlicher Divan (‘West-Eastern Divan’),<br />

12 books of poetry written between 1814 and<br />

1819 which were inspired by the Persian poet<br />

Hafez, whom Goethe had read in a translation<br />

by Joseph von Hammer. The style of these<br />

poems is quite different from Goethe’s earlier<br />

work, being a mixture of arguments, parables<br />

and religious thoughts that bring together East<br />

and West. Wie sollte ich heiter bleiben is taken<br />

from the ‘Book of Zuleika’ and is of thoughts of<br />

love that the poet is finding it hard to express.<br />

‘When she enticed me to her, There was need<br />

of words. And my tongue faltered, So my quill<br />

did too.’ Wolf matches the this pair of conflicting<br />

desires in his piano part and for once there is a<br />

happy ending to the song, at least musically.<br />

Eduard Mörike belongs to the generation of<br />

German poets after Goethe, although his lyrics<br />

are often compared to the older writers. Born in<br />

1804 he studied theology at Tübingen University<br />

becoming a Lutheran pastor, a career that<br />

held little charm for him. So in 1834 he retired<br />

and devoted the remaining 41 years of his life<br />

4

to literature. His language is plain and simple<br />

and his humour down-to-earth. Yet if Mörike’s<br />

poetry seems genial, sometimes bucolic, there<br />

is also a dark edge to many of his poems,<br />

reminding the reader of a deep wound that<br />

seems to have been caused by his falling in love<br />

and being rejected by Maria Mayer, a barmaid<br />

who belonged to an itinerant religious sect<br />

whom he had met at the age of 19. So Denk’<br />

es, o Seele! invites us to think on the rose bush<br />

that will grow on our grave and the two black<br />

horses that will pull our hearse. A poem that<br />

shines in its modesty which Wolf, ever sensitive<br />

to the nuances of a text, matches with silences.<br />

Um Mitternacht is one of Eduard Mörike’s<br />

greatest poems, complete with the arch-<br />

Romantic imagery of mountains, rushing streams<br />

and dark blue skies at the end of a day. So Wolf<br />

begins his setting with a rocking lullaby theme<br />

that somehow slides into sleep in the postlude.<br />

In Auf eine Christblume II, Mörike remembers<br />

for a second time a Christmas rose that he had<br />

come upon in a churchyard. He transplanted<br />

it to a window box where a wind uprooted<br />

the plant. These simple things lead the poet<br />

to a poem on a butterfly ‘that one day over<br />

hill and dale will shake its velvet wings in<br />

spring nights’. But is this is a meditation on the<br />

sleeping soul suddenly awakened? Wolf builds<br />

his song from a two-bar cell for the piano<br />

marked ‘very tender and throughout pp’. An<br />

immaculate match between words and music.<br />

Lied eines Verliebten is a lover’s song with a<br />

twist, a tale with a sting. The lover wakes with<br />

an aching heart before first light, envying the<br />

carefree fisherman or the miller’s lad still asleep<br />

before their happy working day begins. The<br />

lover tosses and turns in Wolf’s part for the<br />

pianist’s left hand. But the chromatic tonality<br />

suggests that there’s self-pity in this lover’s<br />

lament. As Goethe said, something unique has<br />

happened when Mörike’s words meet music.<br />

Franz Schubert<br />

Schubert is the stone on which all German<br />

Lieder composers have stubbed their toes<br />

since his death in 1828 at the age of just 31.<br />

And you could argue that the choices of poets<br />

made by Schubert would influence the next two<br />

generations of German composers. If Schubert<br />

selected poetry that he admired, he also set<br />

lyrics that he liked, including the work of his<br />

friends. The poem Alinde was written by Johann<br />

Friedrich Rochlitz, a poet, novelist and journalist<br />

from Leipzig, who met Schubert in Vienna in<br />

1822 and who became an enthusiastic supporter<br />

of the composer’s music. Schubert repaid the<br />

compliment and dedicated the completed<br />

song to Rochlitz. If the poem is conventional,<br />

the musical setting is elegantly well matched.<br />

This is a gift of friendship that might be read<br />

and sung in any salon with artistic ambitions.<br />

Friedrich Schlegel is one of the founding fathers<br />

of German Romanticism, a literary critic,<br />

philosopher, philologist and poet, who had a<br />

profound effect on Samuel Taylor Coleridge<br />

and thus upon English Romanticism. Together<br />

with his wife Dorothea – the daughter of the<br />

philosopher Moses Mendelssohn and aunt of<br />

Felix Mendelssohn – and his younger brother<br />

Wilhelm – he established the cultural precedents<br />

for Romanticism and many of its themes and<br />

topics. It was Friedrich Schlegel who declared<br />

that ‘Romantic poetry is a progressive universal<br />

poetry’.<br />

Der Wanderer, not to be confused with the<br />

song with the same title that provided the<br />

chief theme for Schubert’s Wanderer-Fantasie,<br />

is the introductory poem to the second<br />

part of Schlegel’s collection Abendröte.<br />

And if Schubert’s other poet’s ‘wanderers’<br />

are Romantic outsiders, at odds with their<br />

surroundings – as in Winterreise – Schlegel’s<br />

traveller is at one with the world. Here, travelling<br />

is a kind of freedom and not an escape<br />

from heavy days and endless troubles.<br />

Herbstlied was composed in 1816 but had to<br />

wait until 1872 for publication. It is the bestknown<br />

of the settings that the composer made<br />

of poems by Johann Gaudenz Freiherr von<br />

Salis-Seewis, a soldier with literary ambitions.<br />

Salis-Seewis served in the Swiss Guards in Paris<br />

until the Revolution in 1789, and is said to have<br />

been a particular favourite of Marie-Antoinette.<br />

A Wanderjahr through Germany that included<br />

meetings with Herder, Goethe, Schiller and the<br />

poet Wieland in Weimar turned his mind to an<br />

early Romantic style of writing which combined<br />

a deep appreciation of nature with a love of<br />

Heimat. His poetry has an elegiac quality that<br />

surely appealed to Schubert. Autumn is indeed<br />

a time for melancholy, ‘when red leaves fall,<br />

grey mists surge [and] the wind blows colder.’<br />

It was Johann Gottfried Herder himself who<br />

provided the text for Schubert’s Verklärung. But<br />

5 Programme notes

the words are not his. The text is a translation<br />

of Alexander Pope’s poem Transfiguration,<br />

which ends with the celebrated couplet ‘O<br />

grave, where is thy victory? O death, where is<br />

thy sting?’ taken from St Paul’s First Letter to the<br />

Corinthians and which haunted 19th-century<br />

hymn writers. It was from the philosopher<br />

Immanuel Kant, who had taught Herder, that<br />

the younger German writer had acquired his<br />

love of Pope. We can only guess at Schubert’s<br />

reaction to the source of the poem he set as<br />

Verklärung, but its sentiment – exaltation at the<br />

defeat of death – must surely have appealed to<br />

a composer so conscious of his own mortality.<br />

Johannes Brahms<br />

Brahms does not always feel like a natural<br />

songwriter, despite the fact that he composed<br />

over 200 Lieder. There’s little sense of his songs<br />

spilling out from his imagination as they did<br />

for his mentor Schumann. There’s something<br />

hard-earned about this composer’s songs, they<br />

can feel ‘worked’ rather than spontaneous. And<br />

there’s the all-pervading feeling of autumn in<br />

many of them. That may perhaps say something<br />

generally about Brahms as a composer<br />

although Schoenberg would describe him as<br />

the ‘conservative revolutionary’. However, in<br />

no way does it diminish the quality of his best<br />

songs, in which the piano part is invariably at the<br />

service of the poem. And Brahms undoubtedly<br />

had an ear for poetry from his earliest years.<br />

Verzagen (‘Despondency’) was published as one<br />

of a group of four songs in 1877. This gloomy<br />

poem was by the art historian Karl Lemcke who,<br />

after studying and teaching at Heidelberg,<br />

moved to Munich in 1871 where he became a<br />

member of the circle of writers known as Die<br />

Krokodile, taking the nickname ‘Hyena’. Unlike<br />

others of their German generation, notably<br />

the Junges Deutschland Group, the Crocodiles<br />

abjured politics in their poetry. For them it was a<br />

holy art that took its cue from classical, medieval<br />

and even Oriental models. And by the time<br />

Lemcke arrived in Munich there was an odour<br />

of late-Romantic angst in the group’s work<br />

that would surely have appealed to the stoic in<br />

Brahms. As Lemcke writes: ‘Du ungestümes Herz<br />

sei still Und gib dich doch zur Ruh’ (You, unruly<br />

heart, be silent, And surrender yourself to rest).<br />

In Über die Heide, published as one of a set of<br />

six songs in 1882, Brahms returned to his roots<br />

in Northern Germany. Theodor Storm was one<br />

of the most prominent 19th-century German<br />

Realist writers. He was also a child of the same<br />

North Sea plain that had nurtured a young<br />

Brahms, and over the course of 50 novellas and<br />

his poetry, Storm celebrates the austere beauty<br />

of this landscape, the mud flats that seem to<br />

stretch for ever, the sea that constantly threatens<br />

and the hard-won pastures. It is the simplicity of<br />

this vision that makes Über die Heide (‘Over the<br />

heath’), such a fine poem and Brahms rises to<br />

the challenge of setting it to music magnificently.<br />

Nachtigallen schwingen is among the earliest<br />

of Brahms’s songs, from a group of six that<br />

were published in 1853 when the composer<br />

was just 20. Steeped in Romantic writers such<br />

as Eichendorff, Heine and E T A Hoffmann, he<br />

would have also have read August Heinrich<br />

Hoffmann, one of the most popular German<br />

poets in the middle years of the 19th century.<br />

Progressive in his politics, Hoffmann wrote poetry<br />

that can be read as a harbinger of the 1848<br />

revolutions, and indeed it was he who wrote<br />

the words for what has become the German<br />

national anthem. But what his contemporaries<br />

admired in his poetry was the plain and<br />

unadorned manner in which he gave expression<br />

to the ‘passions and aspirations of daily life’.<br />

These virtues are present in Nachtigallen<br />

schwingen. These nightingales are no figment<br />

of the Romantic poet’s overheated imagination,<br />

no ‘immortal birds … not born for death’, but<br />

a simple natural miracle. And by the end of<br />

Brahms’s song, words are just about superfluous:<br />

the music has worked its own magic with them.<br />

Programme note © Christopher Cook<br />

6

Texts<br />

Arnold Schoenberg<br />

Erwartung, Op. 2 No. 1<br />

Aus dem meergrünen Teiche<br />

Neben der roten Villa<br />

Unter der toten Eiche<br />

Scheint der Mond.<br />

Wo ihr dunkles Abbild<br />

Durch das Wasser greift,<br />

Steht ein Mann und streift<br />

Einen Ring von seiner Hand.<br />

Drei Opale blinken;<br />

Durch die bleichen Steine<br />

Schwimmen rot und grüne<br />

Funken und versinken.<br />

Und er küsst sie, und<br />

Seine Augen leuchten<br />

Wie der meergrüne Grund:<br />

Ein Fenster tut sich auf.<br />

Aus der roten Villa<br />

Neben der toten Eiche<br />

Winkt ihm eine bleiche<br />

Frauenhand.<br />

Richard Dehmel (1863–1920)<br />

Hanns Eisler<br />

Spruch 1939<br />

In den finsteren Zeiten,<br />

wird da noch gesungen werden?<br />

Ja! Da wird gesungen werden<br />

von den finsteren Zeiten.<br />

Unter den grünen Pfefferbäumen<br />

Unter den grünen Pfefferbaümen<br />

Gehen die Musiker auf den Strich, zwei und zwei<br />

Mit den Schreibern. Bach<br />

Hat ein Strichquartett im Täschen. Dante schwenkt<br />

Den dürren Hintern.<br />

In den Hügeln wird Gold gefunden<br />

In den Hügeln wird Gold gefunden.<br />

An der Küste findet man Öl.<br />

Expectation<br />

From the sea-green pond<br />

near the red villa<br />

beneath the dead oak<br />

shines the moon.<br />

Where her dark reflection<br />

stretches out through the water<br />

stands a man and takes<br />

a ring from his hand.<br />

Three opals glitter;<br />

through the pale stones<br />

swim red and green<br />

sparks and sink.<br />

And he kisses her,<br />

and his eyes shine<br />

like the sea-green ground:<br />

a window is opened.<br />

From the red villa<br />

near the dead oak<br />

a lady’s hand<br />

waves to him<br />

Proverb 1939<br />

In the dark times<br />

will there also be singing?<br />

Yes, there will also be singing<br />

about the dark times.<br />

Underneath the green pepper trees<br />

Underneath the green pepper trees, daily<br />

the composers are on the beat, two by two<br />

with the writers. Bach<br />

writes concertos for the strumpet. Dante wriggles<br />

his shrivelled arsehole.<br />

In the hills are the gold prospectors<br />

In the hills are the gold prospectors.<br />

By the sea you come upon oil.<br />

7 Texts

Grössere Vermögen<br />

Bringen die Träume vom Glück,<br />

Die man hier auf Zelluloid schreibt.<br />

Diese Stadt hat mich belehrt<br />

Diese Stadt Hollywood hat mich belehrt<br />

Paradies und Hölle können eine Stadt sein.<br />

Für die Mittellosen<br />

Ist das Paradies die Hölle.<br />

Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956)<br />

Greater fortunes far<br />

are won from those dreams of happiness<br />

which are kept on celluloid spools.<br />

This city has made me realise<br />

This city of Hollywood has made me realise:<br />

Paradise and hell-fire are the same city.<br />

For the unsuccessful<br />

Paradise itself serves as hell-fire.<br />

Translations by John Willett<br />

Zwei Lieder nach Worten von Pascal<br />

Despite these miseries<br />

Despite these miseries, man wishes to be happy,<br />

and only wishes to be happy, and cannot wish not<br />

to be so. But how will he set about it? To be happy<br />

he would have to make himself immortal. But,<br />

not being able to do so, it has occurred to him to<br />

prevent himself from thinking of death.<br />

The only thing<br />

The only thing which consoles us for our miseries<br />

is diversion, and yet this is the greatest of our<br />

miseries. For it is this which principally hinders<br />

us from reflecting upon ourselves, and which<br />

makes us insensibly ruin ourselves. Without this<br />

we should be in a state of weariness, and this<br />

weariness would spur us to seek a more solid<br />

means of escaping from it. But diversions amuse<br />

us and lead us unconsciously to death.<br />

Blaise Pascal (1623–62)<br />

Erinnerung an Eichendorff und Schumann<br />

Aus der Heimat hinter den Blitzen rot,<br />

Da kommen die Wolken her.<br />

Aber Vater und Mutter sind lange tot,<br />

Es kennt mich dort niemand mehr.<br />

Joseph von Eichendorff (1788–1857)<br />

Verfehlte Liebe<br />

Zuweilen dünkt es mich, als trübe<br />

Geheime Sehnsucht deinen Blick.<br />

Ich kenn es wohl, dein Missgeschick.<br />

Verfehltes Leben, verfehlte Liebe.<br />

Du blickst so traurig, wiedergeben<br />

Kann ich dir nicht die Jugendzeit.<br />

Unheilbar ist dein Herzleid:<br />

Verfehlte Liebe, verfehlte Leben.<br />

Heinrich Heine (1797–1856)<br />

Souvenir of Eichendorff and Schumann<br />

From my homeland, beyond those streaks of red,<br />

that is where all the clouds appear.<br />

But my mother and father are long since dead<br />

and nobody knows me here.<br />

Translation by John Willett<br />

Wasted love<br />

Sometimes it seems to me that<br />

a secret longing dimmed your glance.<br />

I know your sorrow well.<br />

Wasted life, wasted love.<br />

You look so sad, I cannot<br />

give you back your youth.<br />

Incurable is your pain:<br />

wasted love, wasted life.<br />

Translation by Lindsay Craig<br />

8

Spruch<br />

Dies ist nun alles und ist nicht genug.<br />

Doch sagt es euch vielleicht, ich bin noch da.<br />

Dem gleich ich, der den Backstein mit sich trug<br />

Der Welt zu zeigen, wie sein Haus aussah.<br />

Bertolt Brecht<br />

Benjamin Britten<br />

Songs and Proverbs of William Blake<br />

Proverb I<br />

The pride of the peacock is the glory of God.<br />

The lust of the goat is the bounty of God.<br />

The wrath of the lion is the wisdom of God.<br />

The nakedness of woman is the work of God.<br />

London<br />

I wander thro’ each charter’d street,<br />

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow<br />

And mark in every face I meet<br />

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.<br />

In every cry of every Man,<br />

In every Infant’s cry of fear,<br />

In every voice, in every ban,<br />

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear.<br />

How the Chimney-sweeper’s cry<br />

Every black’ning Church appalls,<br />

And the hapless Soldier’s sigh<br />

Runs in blood down Palace walls.<br />

But most thro’ midnight streets I hear<br />

How the youthful Harlot’s curse<br />

Blasts the new-born Infant’s tear<br />

And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse.<br />

Proverb II<br />

Prisons are built with stones of Law,<br />

Brothels with bricks of Religion.<br />

The Chimney-Sweeper<br />

A little black thing among the snow,<br />

Crying weep weep in notes of woe!<br />

Where are thy father and mother? say?<br />

They are both gone up to the church to pray.<br />

Because I was happy upon the heath,<br />

And smil’d among the winter’s snow<br />

They clothed me in the clothes of death,<br />

And taught me to sing the notes of woe.<br />

Proverb<br />

This, then, is all. It’s not enough, I know.<br />

At least I’m still alive, as you may see.<br />

I’m like the man who took a brick to show<br />

how beautiful his house used once to be.<br />

Translation by John Willett<br />

9 Texts

And because I am happy and dance and sing<br />

They think they have done me no injury,<br />

And are gone to praise God and his Priest<br />

and King<br />

Who make up a heaven of our misery.<br />

Proverb III<br />

The bird a nest, the spider a web, man friendship.<br />

A Poison Tree<br />

I was angry with my friend:<br />

I told my wrath, my wrath did end.<br />

I was angry with my foe:<br />

I told it not, my wrath did grow.<br />

And I water’d it in fears,<br />

Night and morning with my tears;<br />

And I sunned it with smiles,<br />

And with soft deceitful wiles.<br />

And it grew both day and night,<br />

Till it bore an apple bright.<br />

And my foe beheld it shine,<br />

And he knew that it was mine.<br />

And into my garden stole<br />

When the night had veil’d the pole,<br />

In the morning glad I see<br />

My foe outstretch’d beneath the tree.<br />

Proverb IV<br />

Think in the morning. Act in the noon. Eat in the<br />

evening. Sleep in the night.<br />

The Tyger<br />

Tyger! Tyger! burning bright<br />

In the forests of the night:<br />

What immortal hand or eye<br />

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?<br />

In what distant deeps or skies<br />

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?<br />

On what wings dare he aspire?<br />

What the hand dare seize the fire?<br />

And what shoulder, and what art,<br />

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?<br />

And when thy heart began to beat,<br />

What dread hand? and what dread feet?<br />

When the stars threw down their spears,<br />

And water’d heaven with their tears,<br />

Did he smile his work to see?<br />

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?<br />

Tyger! Tyger! burning bright<br />

In the forests of the night:<br />

What immortal hand or eye<br />

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?<br />

Proverb V<br />

The tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of<br />

instruction.<br />

If the fool would persist in his folly he would<br />

become wise.<br />

If others had not been foolish, we should be so.<br />

The Fly<br />

Little Fly,<br />

Thy summer’s play<br />

My thoughtless hand<br />

Has brush’d away.<br />

Am not I<br />

A fly like thee?<br />

Or art not thou<br />

A man like me?<br />

For I dance<br />

And drink and sing:<br />

Till some blind hand<br />

Shall brush my wing.<br />

If thought is life<br />

And strength and breath<br />

And the want<br />

Of thought is death;<br />

Then am I<br />

A happy fly,<br />

If I live,<br />

Or if I die.<br />

Proverb VI<br />

The hours of folly are measur’d by the clock; but<br />

of wisdom, no clock can measure.<br />

The busy bee has no time for sorrow.<br />

Eternity is in love with the productions of time.<br />

What the hammer? what the chain?<br />

In what furnace was thy brain?<br />

What the anvil? what dread grasp<br />

Dare its deadly terrors clasp?<br />

10

Ah, Sun-flower<br />

Ah, Sun-flower! weary of time,<br />

Who countest the steps of the Sun;<br />

Seeking after that sweet golden clime,<br />

Where the traveller’s journey is done:<br />

Where the Youth pined away with desire,<br />

And the pale Virgin shrouded in snow,<br />

Arise from their graves and aspire<br />

Where my Sun-flower wishes to go.<br />

Proverb VII<br />

To see a World in a Grain of Sand,<br />

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,<br />

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand,<br />

And Eternity in an hour.<br />

Every Night and every Morn<br />

Every Night and every Morn<br />

Some to Misery are Born.<br />

Every Morn and every Night<br />

Some are Born to sweet delight.<br />

Some are Born to sweet delight,<br />

Some are Born to Endless Night.<br />

We are led to Believe a Lie<br />

When we see not Thro’ the Eye,<br />

Which was Born in a Night, to perish in a Night,<br />

When the Soul Slept in Beams of Light.<br />

God Appears and God is Light<br />

To those poor Souls who dwell in Night,<br />

But does a Human Form Display<br />

To those who Dwell in Realms of Day.<br />

William Blake (1757–1827)<br />

interval: 20 minutes<br />

11 Texts

Hugo Wolf<br />

Mörike Lieder: No 39 Denk’ es, o Seele!<br />

Ein Tännlein grünet wo,<br />

Wer weiss, im Walde,<br />

Ein Rosenstrauch, wer sagt,<br />

In welchem Garten?<br />

Sie sind erlesen schon,<br />

Denk’ es, o Seele,<br />

Auf deinem Grab zu wurzeln<br />

Und zu wachsen.<br />

Zwei schwarze Rösslein weiden<br />

Auf der Wiese,<br />

Sie kehren heim zur Stadt<br />

In muntern Sprüngen.<br />

Sie werden schrittweis gehn<br />

Mit deiner Leiche;<br />

Vielleicht, vielleicht noch eh<br />

An ihren Hufen<br />

Das Eisen los wird,<br />

Das ich blitzen sehe!<br />

Consider, O soul<br />

A little fir-tree flourishes,<br />

who knows where, in the wood;<br />

a rosebush, who can tell<br />

in what garden?<br />

They are selected already,<br />

consider, O soul,<br />

to take root and grow<br />

on your grave.<br />

Two young black horses graze<br />

on the pasture,<br />

they return back to town<br />

with lively leaps.<br />

They will go step by step<br />

with your corpse;<br />

perhaps, perhaps even before<br />

on their hooves<br />

the shoe gets loose,<br />

that I can see sparkle.<br />

Translation by Jakob Kellner<br />

No 19 Um Mitternacht<br />

Gelassen stieg die Nacht ans Land,<br />

Lehnt träumend an der Berge Wand,<br />

Ihr Auge sieht die goldne Waage nun<br />

Der Zeit in gleichen Schalen stille ruhn;<br />

Und kecker rauschen die Quellen hervor,<br />

Sie singen der Mutter, der Nacht, ins Ohr<br />

Vom Tage, vom heute gewesenen Tage.<br />

Das uralt alte Schlummerlied,<br />

Sie achtets nicht, sie ist es müd;<br />

Ihr klingt des Himmels Bläue süsser noch,<br />

Der flüchtgen Stunden gleichgeschwungnes Joch.<br />

Doch immer behalten die Quellen das Wort,<br />

Es singen die Wasser im Schlafe noch fort<br />

Vom Tage, vom heute gewesenen Tage.<br />

Eduard Mörike (1804–75)<br />

At midnight<br />

The night ascends calmly over the land,<br />

leaning dreamily against the<br />

wall of the mountain,<br />

its eyes now resting on the golden scales<br />

of time, in a similar poise of quiet peace;<br />

and boldly murmur the springs,<br />

singing to Mother Night, in her ear,<br />

of the day that was today.<br />

To the ancient lullaby<br />

she pays no attention; she is weary.<br />

To her, the blue heaven sounds sweeter,<br />

the curved yoke of fleeing hours.<br />

Yet the springs keep murmuring,<br />

and the water keeps singing in slumber<br />

of the day that was today.<br />

Translation by Emily Ezust<br />

Wie sollte ich heiter bleiben<br />

Wie sollte ich heiter bleiben,<br />

Entfernt von Tag und Licht?<br />

Nun aber will ich schreiben,<br />

Und trinken mag ich nicht.<br />

Wenn sie mich an sich lockte,<br />

War Rede nicht im Brauch,<br />

Und wie die Zunge stockte,<br />

So stockt die Feder auch.<br />

How could I remain cheerful<br />

How could I remain cheerful,<br />

when parted from day and light?<br />

But now I shall write,<br />

and do not wish to drink.<br />

When she enticed me to her,<br />

there was no need of words;<br />

and as my tongue faltered,<br />

so my quill did too.<br />

12

Nur zu! geliebter Schenke,<br />

Den Becher fülle still!<br />

Ich sage nur: Gedenke!<br />

Schon weiss man, was ich will.<br />

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832)<br />

Mörike Lieder: No 21 Auf eine Christblume II<br />

Im Winterboden schläft, ein Blumenkeim,<br />

Der Schmetterling, der einst um Busch und Hügel<br />

In Frühlingsnächten wiegt den samtnen Flügel;<br />

Nie soll er kosten deinen Honigseim.<br />

Wer aber weiss, ob nicht sein zarter Geist,<br />

Wenn jede Zier des Sommers hingesunken,<br />

Dereinst, von deinem leisen Dufte trunken,<br />

Mir unsichtbar, dich blühende umkreist?<br />

Eduard Mörike<br />

Blumengruss<br />

Der Strauss, den ich gepflücket,<br />

Grüsse dich vieltausendmal!<br />

Ich habe mich oft gebücket,<br />

Ach, wohl eintausendmal,<br />

Und ihn ans Herz gedrücket<br />

Wie hunderttausendmal!<br />

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe<br />

Mörike Lieder: No 43 Lied eines Verliebten<br />

In aller Früh, ach, lang vor Tag,<br />

Weckt mich mein Herz, an dich zu denken,<br />

Da doch gesunde Jugend schlafen mag.<br />

Hell ist mein Aug um Mitternacht,<br />

Heller als frühe Morgenglocken:<br />

Wann hättst du je am Tage mein gedacht?<br />

Wär ich ein Fischer, stünd ich auf,<br />

Trüge mein Netz hinab zum Flusse,<br />

Trüg herzlich froh die Fische zum Verkauf.<br />

In der Mühle, bei Licht, der Mühlerknecht<br />

Tummelt sich, alle Gänge klappern;<br />

So rüstig Treiben wär mir eben recht!<br />

Weh, aber ich! o armer Tropf!<br />

Muss auf dem Lager mich müssig grämen,<br />

Ein ungebärdig Mutterkind im Kopf.<br />

Eduard Mörike<br />

But come, dear Saki,<br />

fill my cup in silence!<br />

I’ve only to say: ‘Remember!’<br />

And my meaning is clear.<br />

On a Christmas rose II<br />

There sleeps within the wintry ground,<br />

flower-seed-like,<br />

The butterfly that one day over hill and dale<br />

will flutter its velvet wings in spring nights.<br />

Never shall it taste your viscous honey.<br />

But who knows if perhaps its gentle ghost,<br />

when summer’s loveliness has faded,<br />

Might some day, dizzy with your faint fragrance,<br />

circle, unseen by me, around you as you flower?<br />

Flower greeting<br />

May this garland I have gathered<br />

greet you many thousand times!<br />

I have often stooped down,<br />

ah, at least a thousand times,<br />

and pressed it to my heart<br />

something like a hundred thousand!<br />

Lover’s song<br />

At first dawn, ah! long before day,<br />

my heart wakes me to think of you,<br />

when healthy lads still are sleeping.<br />

My eyes are bright at midnight,<br />

brighter than early morning bells:<br />

when did you ever think of me by day?<br />

If I were a fisherman, I’d get up,<br />

carry my net down to the river,<br />

happily carry the fish to market.<br />

At first light the miller’s lad<br />

is hard at work, the machinery clatters;<br />

such hearty work would suit me well!<br />

But I poor wretch<br />

must lie idly grieving on my bed,<br />

obsessed with that unruly girl!<br />

Translations by Richard Stokes<br />

13 Texts

Franz Schubert<br />

Alinde, D904<br />

Die Sonne sinkt ins tiefe Meer,<br />

Da wollte sie kommen.<br />

Geruhig trabt der Schnitter einher,<br />

Mir ist’s beklommen.<br />

‘Hast, Schnitter, mein Liebchen nicht gesehn?<br />

Alinde, Alinde!’<br />

‘Zu Weib und Kindern muss ich gehn,<br />

Kann nicht nach andern Dirnen sehn;<br />

Sie warten mein unter der Linde.’<br />

Der Mond betritt die Himmelsbahn,<br />

Noch will sie nicht kommen.<br />

Dort legt der Fischer das Fahrzeug an,<br />

Mir ist’s beklommen.<br />

‘Hast, Fischer, mein Liebchen nicht gesehn?<br />

Alinde, Alinde!’<br />

‘Muss suchen, wie mir die Reusen stehn,<br />

Hab nimmer Zeit nach Jungfern zu gehn,<br />

Schau, welch einen Fang ich finde.’<br />

Die lichten Sterne ziehn herauf,<br />

Noch will sie nicht kommen.<br />

Dort eilt der Jäger in rüstigem Lauf,<br />

Mir ist’s beklommen.<br />

‘Hast, Jäger, mein Liebchen nicht gesehn?<br />

Alinde, Alinde!’<br />

‘Muss nach dem bräunlichen Rehbock gehn,<br />

Hab nimmer Lust nach Mädeln zu sehn;<br />

Dort schleicht er im Abendwinde.’<br />

In schwarzer Nacht steht hier der Hain,<br />

Noch will sie nicht kommen.<br />

Von allen Lebendgen irr ich allein,<br />

Bang und beklommen.<br />

‘Dir, Echo, darf ich mein Leid gestehn:<br />

Alinde, Alinde!’<br />

‘Alinde,’ liess Echo leise herüberwehn;<br />

Da sah ich sie mir zur Seite stehn:<br />

‘Du suchtest so treu, nun finde!’<br />

Alinde<br />

The sun sinks into the deep ocean,<br />

she was due to come.<br />

Calmly the reaper walks by.<br />

My heart is heavy.<br />

‘Reaper, have you not seen my love?<br />

Alinda! Alinda!’<br />

‘I must go to my wife and children,<br />

I cannot look for other girls.<br />

They are waiting for me beneath the linden tree.’<br />

The moon entered its heavenly course,<br />

she still does not come.<br />

There a fisherman lands his boat.<br />

My heart is heavy.<br />

‘Fisherman, have you not seen my love?<br />

Alinda! Alinda!’<br />

‘I must see how my oyster baskets are,<br />

I never have time to chase after girls;<br />

look what a catch I have!’<br />

The bright stars appear,<br />

she still does not come.<br />

The huntsman rides swiftly along.<br />

My heart is heavy.<br />

‘Huntsman, have you not seen my love?<br />

Alinda! Alinda!’<br />

‘I must go after the brown roebuck,<br />

I never care to look for girls;<br />

there he goes in the evening breeze!’<br />

The grove lies here in blackest night,<br />

she still does not come.<br />

I wander alone, away from all mankind,<br />

anxious and troubled.<br />

‘To you, Echo, I confess my sorrow:<br />

Alinda! Alinda!’<br />

‘Alinda’, came the soft echo;<br />

Then I saw her at my side.<br />

‘You searched so faithfully. Now you find me.’<br />

Johann Friedrich Rochlitz (1769–1842)<br />

14<br />

Der Wanderer, D649<br />

Wie deutlich des Mondes Licht<br />

Zu mir spricht,<br />

Mich beseelend zu der Reise:<br />

‘Folge treu dem alten Gleise,<br />

Wähle keine Heimat nicht.<br />

Ew’ge Plage<br />

Bringen sonst die schweren Tage;<br />

The traveller<br />

How clearly the moon’s light<br />

speaks to me,<br />

inspiring me on my journey:<br />

‘Follow faithfully the old track,<br />

choose nowhere as your home,<br />

lest bad times<br />

bring endless cares.

Fort zu andern<br />

Sollst du wechseln, sollst du wandern,<br />

Leicht entfliehend jeder Klage.’<br />

Sanfte Ebb’ und hohe Flut,<br />

Tief im Mut,<br />

Wandr’ ich so im Dunkeln weiter,<br />

Steige mutig, singe heiter,<br />

Und die Welt erscheint mir gut.<br />

Alles reine<br />

Seh’ ich mild im Widerscheine,<br />

Nichts verworren<br />

In des Tages Glut verdorren:<br />

Froh umgeben, doch alleine.<br />

Friedrich von Schlegel (1772–1829)<br />

Herbstlied, D502<br />

Bunt sind schon die Wälder,<br />

Gelb die Stoppelfelder,<br />

Und der Herbst beginnt.<br />

Rote Blätter fallen,<br />

Graue Nebel wallen,<br />

Kühler weht der Wind.<br />

Wie die volle Traube<br />

Aus dem Rebenlaube<br />

Purpurfarbig strahlt!<br />

Am Geländer reifen<br />

Pfirsiche mit Streifen<br />

Rot und weiss bemalt.<br />

Sieh, wie hier die Dirne<br />

Emsig Pflaum’ und Birne<br />

In ihr Körbchen legt;<br />

Dort, mit leichten Schritten<br />

Jene goldne Quitten<br />

In den Landhof trägt!<br />

Flinke Träger springen,<br />

Und die Mädchen singen,<br />

Alles jubelt froh!<br />

Bunte Bänder schweben<br />

Zwischen hohen Reben<br />

Auf dem Hut von Stroh.<br />

Johann Gaudenz Freiherr von Salis-Seewis<br />

(1762–1834)<br />

Verklärung, D59<br />

Lebensfunke, vom Himmel entglüht,<br />

Der sich loszuwinden müht!<br />

Zitternd-kühn, vor Sehnen leidend,<br />

Gern und doch mit Schmerzen scheidend –<br />

End’, o end’ den Kampf, Natur!<br />

Sanft ins Leben.<br />

You will move on, and go forth<br />

to other places,<br />

lightly casting off all grief.’<br />

Thus, with gentle ebb and swelling flow<br />

deep within my soul,<br />

I walk on in the darkness.<br />

I climb boldly, singing merrily,<br />

and the world seems good to me.<br />

I see all things clearly<br />

in their gentle reflection.<br />

Nothing is blurred<br />

or withered in the heat of the day:<br />

there is joy all around, yet I am alone.<br />

Autumn song<br />

The woods are already brightly coloured,<br />

the fields of stubble yellow,<br />

and autumn is here.<br />

Red leaves fall,<br />

grey mists surge,<br />

the wind blows colder.<br />

How purple shines<br />

the plump grape<br />

from the vine leaves!<br />

On the espalier<br />

peaches ripen<br />

painted with red and white streaks.<br />

Look how busily the maiden here<br />

gathers plums and pears<br />

in her basket;<br />

look how that one there,<br />

with light steps,<br />

carries golden quinces to the house.<br />

The lads dance nimbly<br />

and the girls sing;<br />

all shout for joy.<br />

Amid the tall vines<br />

coloured ribbons flutter<br />

on hats of straw.<br />

Translations by Richard Wigmore<br />

Transfiguration<br />

Vital spark of heav’nly flame!<br />

Quit, O quit this mortal frame:<br />

Trembling, hoping, ling’ring, flying,<br />

O the pain, the bliss of dying!<br />

Cease, fond Nature, cease thy strife,<br />

And let me languish into life.<br />

15 Texts

Aufwärts schweben<br />

Sanft hinschwinden lass mich nur.<br />

Horch! mir lispeln Geister zu:<br />

‘Schwester-Seele, komm zur Ruh!’<br />

Ziehet was mich sanft von innen?<br />

Was ist’s, was mir meine Sinnen<br />

Mir den Hauch zu rauben droht?<br />

Seele, sprich, ist das der Tod?<br />

Die Welt entweicht! sie ist nicht mehr!<br />

Engel-Einklang um mich her!<br />

Ich schweb’ im Morgenrot! –<br />

Leiht, o leiht mir eure Schwingen:<br />

Ihr Bruder-Geister, helft mir singen:<br />

‘O Grab, wo ist dein Sieg?<br />

Wo ist dein Pfeil, o Tod?<br />

Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803)<br />

Hark! they whisper; angels say,<br />

Sister Spirit, come away!<br />

What is this absorbs me quite?<br />

Steals my senses, shuts my sight,<br />

Drowns my spirits, draws my breath?<br />

Tell me, my soul, can this be death?<br />

The world recedes; it disappears!<br />

Heav’n opens on my eyes! my ears<br />

with sounds seraphic ring!<br />

Lend, lend your wings! I mount! I fly!<br />

O Grave! where is thy victory?<br />

O Death! where is thy sting?<br />

Alexander Pope (1688–1744)<br />

Johannes Brahms<br />

Fünf Gesänge, Op 72: No 4 Verzagen<br />

Ich sitz’ am Strande der rauschenden See<br />

Und suche dort nach Ruh’,<br />

Ich schaue dem Treiben der Wogen<br />

Mit dumpfer Ergebung zu.<br />

Die Wogen rauschen zum Strande hin,<br />

Sie schäumen und vergeh’n,<br />

Die Wolken, die Winde darüber,<br />

Die kommen und verweh’n.<br />

Du ungestümes Herz, sei still<br />

Und gib dich doch zur Ruh’;<br />

Du sollst mit Winden und Wogen<br />

Dich trösten – was weinest du?<br />

Despondency<br />

I sit by the shore of the raging sea<br />

Searching there for rest,<br />

I gaze at the waves’ motion<br />

in numb resignation.<br />

The waves crash on the shore,<br />

they foam and vanish,<br />

the clouds, the winds above,<br />

they come and go.<br />

You, unruly heart, be silent<br />

and surrender yourself to rest;<br />

you should find comfort<br />

in winds and waves – why are you weeping?<br />

Karl Lemcke (1831–1913)<br />

Sechs Lieder, Op 86: No 4 Über die Heide<br />

Über die Heide hallet mein Schritt;<br />

Dumpf aus der Erde wandert es mit.<br />

Herbst ist gekommen, Frühling ist weit,<br />

Gab es denn einmal selige Zeit?<br />

Brauende Nebel geisten umher,<br />

Schwarz ist das Kraut und der Himmel so leer.<br />

Wär ich nur hier nicht gegangen im Mai!<br />

Leben und Liebe – wie flog es vorbei!<br />

Over the heath<br />

Over the heath my steps resound;<br />

muffled sounds from the earth wander with me.<br />

Autumn has come, Spring is far distant,<br />

did rapture once really exist?<br />

Swirling mists ghost about,<br />

the heather is black and the sky so empty.<br />

Had I never wandered here in May!<br />

Life and love – how they flew by!<br />

Theodor Storm (1817–88)<br />

16

Sechs Gesänge, Op 6:<br />

No 6 Nachtigallen schwingen<br />

Nachtigallen schwingen<br />

Lustig ihr Gefieder,<br />

Nachtigallen singen<br />

Ihre alten Lieder,<br />

Und die Blumen alle,<br />

Sie erwachen wieder<br />

Bei dem Klang und Schalle<br />

Aller dieser Lieder.<br />

Und meine Sehnsucht wird zur Nachtigall<br />

Und fliegt in die blühende Welt hinein,<br />

Und graft bei den Blumen überall,<br />

Wo mag doch mein mein Blümchen sein?<br />

Und die Nachtigallen<br />

Schwingen ihren Reigen<br />

Unter Laubeshallen<br />

wischen Blütenzweigen,<br />

Vor den Blumen allen<br />

Aber ich muss scheweigen,<br />

Unter ihnen steh ich<br />

Traurig sinnend still;<br />

Eine Blume seh ich,<br />

Die nicht blühen will.<br />

Hoffmann von Fallersleben (1798–1874)<br />

<strong>Barbican</strong> Classical Music Podcasts<br />

Stream or download our <strong>Barbican</strong> Classical Music<br />

Podcasts for exclusive interviews with the world’s greatest<br />

classical stars. Recent artists include Ian Bostridge, Harry<br />

Christophers, Maxim Vengerov, Joyce DiDonato and<br />

many more.<br />

Available on iTunes, Soundcloud and the <strong>Barbican</strong> website<br />

Nightingales joyfully flutter<br />

Nightingales joyfully<br />

flutter their feathers,<br />

nightingales sing<br />

their old songs,<br />

and the flowers<br />

wake again<br />

at the tones and sounds<br />

of all these songs.<br />

And my longing becomes a nightingale<br />

and flies out into the blossoming world,<br />

and asks everywhere of every flower,<br />

where might my own floweret be?<br />

And the nightingales<br />

flutter their dances<br />

beneath leafy arbours<br />

among blossoming boughs,<br />

but I must keep silent<br />

about all the flowers,<br />

I stand among them<br />

sadly lost in silent thought;<br />

I see a flower<br />

that does not wish to bloom.<br />

Translations by Richard Stokes<br />

17 Texts

About the<br />

performers<br />

Uwe Arens<br />

<strong>Simon</strong> <strong>Keenlyside</strong><br />

<strong>Simon</strong> <strong>Keenlyside</strong> baritone<br />

<strong>Simon</strong> <strong>Keenlyside</strong> was born in London. He made<br />

his operatic debut at the Hamburg State Opera<br />

as Count Almaviva (The Marriage of Figaro).<br />

He appears in all the world’s leading opera<br />

houses and has a particularly close association<br />

with the Metropolitan Opera, New York, the<br />

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, and the<br />

Bavarian and Vienna State Opera houses where<br />

his roles include Prospero (Thomas Adès’s The<br />

Tempest), Posa (Don Carlo), Giorgio Germont<br />

(La traviata), Papageno (The Magic Flute)<br />

and the title-roles in Don Giovanni, Eugene<br />

Onegin, Pelléas et Mélisande, Wozzeck, Billy<br />

Budd, Hamlet, Macbeth and Rigoletto. For his<br />

portrayals of Billy Budd at ENO and Winston<br />

(1984) at the Royal Opera House, he won the<br />

2006 Olivier Award for outstanding achievement<br />

in opera. In 2007 he was given the ECHO Klassik<br />

award for Male Singer of the Year, and in 2011<br />

he was honoured with Musical America’s Vocalist<br />

of the Year Award.<br />

He will return to the Royal Opera House<br />

(Rigoletto), the Vienna State Opera (Count<br />

Almaviva and Rigoletto), the Bayerische<br />

Staatsoper (Ford, Giorgio Germont, Posa, Don<br />

Giovanni and Macbeth) and will make many<br />

further appearances at the Metropolitan Opera.<br />

He enjoys extensive concert work and has sung<br />

under the baton of many of the world’s leading<br />

conductors, appearing with the Chamber<br />

Orchestra of Europe, the City of Birmingham and<br />

London Symphony orchestras, Philharmonia and<br />

Cleveland Orchestras and the Vienna and Berlin<br />

Philharmonic orchestras.<br />

A renowned recitalist, <strong>Simon</strong> <strong>Keenlyside</strong> appears<br />

regularly at the world’s major recital venues.<br />

He has recorded a disc of Schumann Lieder<br />

with Graham Johnson and four recital discs<br />

with <strong>Malcolm</strong> <strong>Martineau</strong>, of Schubert, Strauss,<br />

Brahms, and most recently, an English song disc,<br />

Songs of War, which won a 2012 Gramophone<br />

Award.<br />

He has also recorded Britten’s War Requiem<br />

with the London Symphony Orchestra under<br />

Gianandrea Noseda, Mendelssoh’s Elijah<br />

under Paul McCreesh, Mahler’s Des Knaben<br />

Wunderhorn under Sir <strong>Simon</strong> Rattle, the titlerole<br />

in Don Giovanni under Claudio Abbado,<br />

Carmina burana under Christian Thielemann,<br />

Marcello in La bohème under Riccardo Chailly,<br />

the title-role in Billy Budd under Richard Hickox,<br />

Papageno under Charles Mackerras and Count<br />

Almaviva in the Grammy award-winning The<br />

Marriage of Figaro under René Jacobs.<br />

<strong>Simon</strong> <strong>Keenlyside</strong> was made a CBE in 2003.<br />

18

Russell Duncan<br />

<strong>Malcolm</strong> <strong>Martineau</strong><br />

<strong>Malcolm</strong> <strong>Martineau</strong> piano<br />

<strong>Malcolm</strong> <strong>Martineau</strong> was born in Edinburgh, read<br />

Music at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, and<br />

studied at the Royal College of Music.<br />

Recognised as one of the leading accompanists<br />

of his generation, he has worked with many of<br />

the world’s greatest singers including Sir Thomas<br />

Allen, Dame Janet Baker, Olaf Bär, Barbara<br />

Bonney, Ian Bostridge, Angela Gheorghiu, Susan<br />

Graham, Thomas Hampson, Della Jones, <strong>Simon</strong><br />

<strong>Keenlyside</strong>, Angelika Kirchschlager, Magdalena<br />

KoΩená, Solveig Kringelborn, Jonathan Lemalu,<br />

Dame Felicity Lott, Christopher Maltman, Karita<br />

Mattila, Lisa Milne, Ann Murray, Anna Netrebko,<br />

Anne Sofie von Otter, Joan Rodgers, Amanda<br />

Roocroft, Michael Schade, Frederica von Stade,<br />

Sarah Walker and Bryn Terfel.<br />

He has presented his own series at the Wigmore<br />

Hall (a Britten and a Poulenc series and ‘Decade<br />

by Decade – 100 years of German Song’,<br />

broadcast by the BBC) and at the Edinburgh<br />

Festival (the complete Lieder of Hugo Wolf). He<br />

has appeared throughout Europe (including at<br />

the <strong>Barbican</strong>, Queen Elizabeth Hall and Royal<br />

Opera House; La Scala, Milan; the Châtelet,<br />

Paris; the Liceu, Barcelona; Berlin’s Philharmonie<br />

and Konzerthaus; Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw<br />

and the Vienna Konzerthaus and Musikverein),<br />

North America (including in New York both Alice<br />

Tully Hall and Carnegie Hall), Australia (including<br />

the Sydney Opera House) and at the Aix-en-<br />

Provence, Vienna, Edinburgh, Schubertiade,<br />

Munich and Salzburg festivals.<br />

Recording projects have included Schubert,<br />

Schumann and English song recitals with Bryn<br />

Terfel (for DG); Schubert and Strauss recitals with<br />

<strong>Simon</strong> <strong>Keenlyside</strong> (for EMI); recital recordings<br />

with Angela Gheorghiu and Barbara Bonney<br />

(for Decca), Magdalena KoΩená (for DG),<br />

Della Jones (for Chandos), Susan Bullock (for<br />

Crear Classics), Solveig Kringelborn (for NMA);<br />

Amanda Roocroft (for Onyx); the complete Fauré<br />

songs with Sarah Walker and Tom Krause; the<br />

complete Britten folk songs for Hyperion; the<br />

complete Beethoven folk songs for DG; the<br />

complete Poulenc songs for Signum; and Britten<br />

song-cycles as well as Schubert’s Winterreise with<br />

Florian Boesch for Onyx.<br />

This season’s engagements include appearances<br />

with <strong>Simon</strong> <strong>Keenlyside</strong>, Sarah Connolly, Dorothea<br />

Röschmann, John Mark Ainsley, Christoph<br />

Prégardien, Michael Schade, Thomas Oliemans,<br />

Kate Royal, Christiane Karg, Florian Boesch,<br />

Iestyn Davies and Anne Schwanewilms<br />

He was a given an honorary doctorate by the<br />

Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama<br />

in 2004, and appointed International Fellow of<br />

Accompaniment in 2009.<br />

In 2011 <strong>Malcolm</strong> <strong>Martineau</strong> was Artistic Director<br />

of the Leeds Lieder+ Festival.<br />

19 About the performers

Songs and arias of grace and<br />

power from one of the finest<br />

singers alive. Magdalena Kožená<br />

presents a double portrait of<br />

music from two of the greatest<br />

composers of the 18th century.<br />

barbican.org.uk