- Page 1 and 2: INTRODUCTION OPPORTUNITIES AND CHAL

- Page 3 and 4: Forest law enforcement and governan

- Page 5 and 6: ■ Protecting vital local and glob

- Page 7 and 8: Figure 3 Commitment from the World

- Page 9 and 10: Figure 6 Regional Distribution of I

- Page 11 and 12: management and biodiversity conserv

- Page 13: PART I Priority Themes and Operatio

- Page 16 and 17: Angelsen and Wunder 2003; and Malli

- Page 18 and 19: harvesting forest products that are

- Page 20 and 21: forest management and ownership hav

- Page 22 and 23: Institutional development of capaci

- Page 24 and 25: Contreras-Hermosilla, A., and M. Si

- Page 26 and 27: Box 1.4 Poverty-Forest Linkages Too

- Page 28 and 29: Box 1.6 An Overview of the Tools fo

- Page 30 and 31: NOTE 1.2 Community-Based Forest Man

- Page 32 and 33: the biophysical resource through fo

- Page 34 and 35: Box 1.12 Andhra Pradesh Community F

- Page 36 and 37: Box 1.14 Community Forestry in Mexi

- Page 38 and 39: World Bank, 1978. Forestry. Sector

- Page 40 and 41: [Indigenous Peoples’] rights of o

- Page 42 and 43: inappropriate. Thus, development pr

- Page 44 and 45: nity territory into individual plot

- Page 46 and 47: LESSONS LEARNED AND RECOMMENDATIONS

- Page 48 and 49: Borrini-Feyerabend, G., M. Pimbert,

- Page 50 and 51: In what are considered public fores

- Page 54 and 55: Box 1.21 Opportunities to Advance C

- Page 56 and 57: NOTE 1.5 Making Markets Work for th

- Page 58 and 59: ■ environmental groups to produce

- Page 60 and 61: Box 1.25 Medicinal Plants as NTFPs

- Page 63 and 64: CHAPTER 2 Engaging the Private Sect

- Page 65 and 66: dred to tens of thousands of new jo

- Page 67 and 68: Box 2.2 Since 1995, Brazilian small

- Page 69 and 70: Macqueen, D., N. Armitage, M. Jaeck

- Page 71 and 72: NOTE 2.1 COMPANY-COMMUNITY PARTNERS

- Page 73 and 74: inputs (communities), and cost savi

- Page 75 and 76: community arrangements, such as eth

- Page 77 and 78: NOTE 2.2 Small and Medium Enterpris

- Page 79 and 80: must be distinguished from products

- Page 81 and 82: overregulation falls most heavily o

- Page 83 and 84: da Amazônia (IPAM) and the Interna

- Page 85 and 86: NOTE 2.3 Innovative Marketing Arran

- Page 87 and 88: Table 2.2 World Bank Projects with

- Page 89 and 90: payments for reforestation can enco

- Page 91: Wunder, S. 2005. “Payments for En

- Page 94 and 95: Box 3.1 Technical Definitions Wood

- Page 96 and 97: Table 3.2 Wood Fuel Data for Select

- Page 98 and 99: ered it important to have the World

- Page 100 and 101: operations (such as community-based

- Page 102 and 103:

also needs to be extended in many c

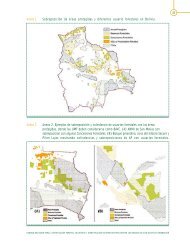

- Page 104 and 105:

NOTE 3.1 Mainstreaming Conservation

- Page 106 and 107:

areas that can be used more intensi

- Page 108 and 109:

Box 3.7 Applying HCVF in Papua New

- Page 110 and 111:

Finally, any existing protections,

- Page 112 and 113:

However, these general rules are se

- Page 114 and 115:

the origin of products from a certi

- Page 116 and 117:

management practices in selected en

- Page 118 and 119:

Reforms) provide the framework for

- Page 120 and 121:

lenges to weak institutions, which

- Page 123 and 124:

CHAPTER 4 Optimizing Forest Functio

- Page 125 and 126:

People and human societies are seen

- Page 127 and 128:

Encourage stakeholder participation

- Page 129 and 130:

Box 4.5 Tradeoffs Framework Used in

- Page 131 and 132:

Sector and Thematic Evaluation, Ope

- Page 133 and 134:

Identify planning team members and

- Page 135 and 136:

Involve relevant stakeholders in de

- Page 137 and 138:

needs of implementing partners and

- Page 139 and 140:

NOTE 4.2 Assessing Outcomes of Land

- Page 141 and 142:

Box 4.13 Possible Indicators for As

- Page 143 and 144:

NOTE 4.3 Using Adaptive Management

- Page 145 and 146:

■ ■ ■ ■ Develop a project p

- Page 147 and 148:

Another important and useful proces

- Page 149 and 150:

theless, it is never too late to st

- Page 151 and 152:

CHAPTER 5 IMPROVING FOREST GOVERNAN

- Page 153 and 154:

Improving forest governance and leg

- Page 155 and 156:

tant part of the World Bank’s con

- Page 157 and 158:

sector with broader governance and

- Page 159 and 160:

NOTE 5.1 Decentralized Forest Manag

- Page 161 and 162:

Assess the overall decentralization

- Page 163 and 164:

Box 5.5 Nicaragua: Asymmetries Betw

- Page 165 and 166:

Parker, A. 1995. “Decentralizatio

- Page 167 and 168:

■ ■ ■ Management of forests (

- Page 169 and 170:

such as designing a transparent con

- Page 171 and 172:

Box 5.11 Citizen Report Cards: Benc

- Page 173 and 174:

NOTE 5.3 Strengthening Legal Framew

- Page 175 and 176:

Box 5.13 Working on the Law with La

- Page 177 and 178:

In addition, the process of public

- Page 179 and 180:

ANNEX 5.3B SIX DRAFTING PRINCIPLES

- Page 181 and 182:

forestry policy or to promote other

- Page 183 and 184:

The most common fiscal incentives i

- Page 185 and 186:

is reasonable to allow the administ

- Page 187 and 188:

ANNEX 5.4A A SUMMARY OF THE DIFFERE

- Page 189 and 190:

NOTE 5.5 ADDRESSING ILLEGAL LOGGING

- Page 191 and 192:

Box 5.17 Measures Specific to Comba

- Page 193 and 194:

■ ■ ■ initially have to compe

- Page 195 and 196:

enterprises may be motivated to joi

- Page 197 and 198:

NOTES 1. This note is based on Worl

- Page 199 and 200:

ANNEX 5.5B TYPICAL CONTEXTS OF ILLE

- Page 201:

Typical contexts Potential drivers

- Page 204 and 205:

Box 6.1 Indonesian Structural Adjus

- Page 206 and 207:

Box 6.2 Upstream Analyses on Energy

- Page 208 and 209:

Box 6.3 Positive Impact of Agrarian

- Page 210 and 211:

Box 6.4 Use of the Rapid CEA Approa

- Page 212 and 213:

———. 2005. “Development Pol

- Page 214 and 215:

NOTE 6.1 Using National Forest Prog

- Page 216 and 217:

Box 6.6 Basic Principles of NFP Pre

- Page 218 and 219:

Implementation. The implementation

- Page 220 and 221:

allow for each country’s differen

- Page 222 and 223:

limited in the coverage and duratio

- Page 224 and 225:

Box 6.12 The Use of DPLs to Support

- Page 226 and 227:

Box 6.13 Using DPLs in Lao PDR for

- Page 228 and 229:

OPCS. 2004. “Good Practice Notes

- Page 230 and 231:

OPERATIONAL ASPECTS Prioritizing th

- Page 232 and 233:

orientation of the DPL operations c

- Page 234 and 235:

Indicators are helpful in these sit

- Page 236 and 237:

ANNEX 6.3A SELECT TOOLS TO ASSIST S

- Page 238 and 239:

NOTE 6.4 Assessing Cross-Sectoral I

- Page 240 and 241:

Box 6.16 The Forests Component in t

- Page 242 and 243:

Considering the above issues, an in

- Page 244 and 245:

Box 6.19 Implementation of the Keny

- Page 246 and 247:

World Bank SEA Web resources: http:

- Page 248 and 249:

Box 7.1 Monitoring Promotes Changes

- Page 250 and 251:

collected via remote sensing rather

- Page 252 and 253:

Discussions and proposals on how to

- Page 254 and 255:

Assessment (www.millenniumassessmen

- Page 256 and 257:

FAO. 2004. “Manual for Environmen

- Page 258 and 259:

■ ■ ■ enables implementation

- Page 260 and 261:

selecting the technology. Technolog

- Page 262 and 263:

USFS Field Guides: www.fia.fs.fed.u

- Page 264 and 265:

Box 7.13 System Architecture of a S

- Page 266 and 267:

Box 7.14 FMIS in Bosnia and Herzego

- Page 268 and 269:

and client-rich system, which would

- Page 270 and 271:

ANNEX 7.2A MODEL TERMS OF REFERENCE

- Page 272 and 273:

■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■

- Page 274 and 275:

NOTE 7.3 Spatial Monitoring of Fore

- Page 276 and 277:

■ ■ ■ ■ Availability of ref

- Page 278 and 279:

Box 7.19 Selecting the Appropriate

- Page 280 and 281:

Table 7.4 Existing Satellite Remote

- Page 282 and 283:

Tropical Ecosystem Environment Obse

- Page 285:

PART II Guidance on Implementing Fo

- Page 288 and 289:

forestry activities was counterprod

- Page 290 and 291:

waterways, or the quantity or quali

- Page 292 and 293:

■ ■ ■ ■ ■ an independent

- Page 294 and 295:

■ In the case of forest harvestin

- Page 296 and 297:

■ ■ harvesting supported by Wor

- Page 298 and 299:

However, some of the World Bank’s

- Page 300 and 301:

■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Examine the

- Page 302 and 303:

Box 9.2 Participation Strategy To m

- Page 304 and 305:

Box 9.5 Process Framework for Invol

- Page 306 and 307:

Box 9.8 Market Analysis A market an

- Page 308 and 309:

“no-project” option); and recom

- Page 310 and 311:

Box 9.16 Environmental Management P

- Page 312 and 313:

■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■

- Page 314 and 315:

the detailed Biodiversidade Brasile

- Page 316 and 317:

■ ■ management plan—prepared

- Page 319 and 320:

CHAPTER 10 Consultation and Communi

- Page 321 and 322:

media, NGOs, other interest groups,

- Page 323 and 324:

Box 10.4 Consultation in the Democr

- Page 325 and 326:

Box 10.6 Elements of Communication

- Page 327 and 328:

Table 10.2 Listening to the Public

- Page 329 and 330:

■ - Preliminary research should i

- Page 331 and 332:

Box 10.8 Managing Risks through Str

- Page 333 and 334:

Bank project cycle related to Commu

- Page 335 and 336:

CHAPTER 11 Forest Certification Ass

- Page 337 and 338:

carried out under a specific certif

- Page 339 and 340:

once more practical experience has

- Page 341 and 342:

ANNEX 11A MODEL TERMS OF REFERENCE

- Page 343 and 344:

ANNEX 11B PROCEDURES AND TERMS OF R

- Page 347 and 348:

CHAPTER 12 Applying OP 4.10 on Indi

- Page 349 and 350:

lack of opportunities relative to o

- Page 351 and 352:

Box 12.2 When a project affects Ind

- Page 353 and 354:

ples receive social and economic be

- Page 355 and 356:

Bank’s supervision team must incl

- Page 357:

ANNEX 12A ELEMENTS OF AN INDIGENOUS

- Page 360 and 361:

forest monitoring, 275b social and

- Page 362 and 363:

FOMAS. See National Forest Sector M

- Page 364 and 365:

and forest certification, 335 toolk

- Page 366 and 367:

applying to Indigenous Peoples, 347

- Page 368 and 369:

strategic partnership, LFI example,

- Page 372:

Eco-Audit Environmental Benefits St