Forests Sourcebook - HCV Resource Network

Forests Sourcebook - HCV Resource Network

Forests Sourcebook - HCV Resource Network

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Box 1.18<br />

Typology of Property Rights<br />

Property rights can be viewed as reflective of social relations.<br />

Property rights are rules that govern relations<br />

between individuals with respect to property and they<br />

should therefore be defined by the community or the<br />

state to which such individuals belong. Property rights<br />

need to be clearly defined, well understood, and<br />

accepted by those who have to abide by them—and<br />

strictly enforced. Property rights need not always confer<br />

full “ownership” and be individual; depending on the<br />

circumstances it may be best if they are bestowed on the<br />

individual, in common, or to the general public. Most<br />

important for sustainable development is that property<br />

rights are deemed secure (van den Brink et al. 2006).<br />

No single typology of tenure or property rights is<br />

universally accepted. Some typologies distinguish<br />

between legal tenure and customary tenure, others<br />

between de facto and de jure rights, while others distinguish<br />

among property regimes. Property rights are also<br />

often seen as a bundle of rights that include the right to<br />

access and withdraw, manage, exclude, and alienate<br />

(Schlager and Ostrom 1992).<br />

Legal tenure is recognized as legitimate under the<br />

policies and laws of the state, while customary tenure is<br />

recognized as legitimate by the traditions and customs<br />

of a society but has not been formally codified in the<br />

law. Customary tenure systems exist in many countries<br />

with significant populations of rural poor, where land<br />

allocation and use are determined through longstanding<br />

“customary” methods that, in many countries,<br />

operate outside the formal legal system. Such customary<br />

tenure systems are dominant in many<br />

indigenous areas where traditional social structures are<br />

largely intact. Customary systems are associated with<br />

traditional land administration institutions and customary<br />

laws that define how rights are governed, allocated,<br />

and preserved. The systems are effective because<br />

they respond to a community’s social, cultural, and<br />

economic needs and because they are enforced by local<br />

leadership. Customary tenure systems typically possess<br />

both collective and individual dimensions. In part, the<br />

collective aspect relates to the community as compared<br />

with outsiders. Internally, the collective element relates<br />

to community land and resources, while the individual<br />

dimension concerns transactions, successions, and<br />

exchanges of family plots between community members.<br />

While it is reasonable to consider that both collective<br />

and individual tenure have their place in forest<br />

activities, introducing individual tenure from outside<br />

includes risks.<br />

There are cases where customary rights have been<br />

legitimized but are still identified as customary rights.<br />

In such cases, the term “customary” helps identify the<br />

origin of the right. De jure rights are given lawful<br />

recognition by formal, legal instrumentalities, while de<br />

facto rights are rights that resource users continuously<br />

work cooperatively to design and enforce.<br />

A common typology of property rights distinguishes<br />

among private, common, and public or state<br />

property rights:<br />

■<br />

■<br />

■<br />

■<br />

Private property rights<br />

– individual or “legal individual” holds most if not<br />

all the rights<br />

– property can be leased under a contract to a third<br />

party<br />

Common property rights<br />

– group (for example, community) holds rights<br />

– group can manage property and exclude others<br />

– rules are important to manage and distribute<br />

resource<br />

Public property or state property rights<br />

State holds the bundle of rights<br />

Open access results from the ineffective exclusion of<br />

nonowners by the entity assigned formal rights of<br />

ownership.<br />

Source: Authors’ compilation using Molnar and Khare (2006) and Jensby (2007).<br />

different set of opportunities for communities to use and<br />

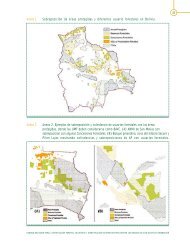

protect their resources with varying outcomes (figure 1.1).<br />

While government statistics and information available<br />

from land administrations are usually a good starting point,<br />

greater insights concerning evidence of historical use and<br />

dependence, as well as customary laws and rights, are often<br />

gathered through participatory mapping.<br />

Importance of pilots. Pilot activities can be important to<br />

expanding the range of possibilities, demonstrating the<br />

viability of rights-based forestry approaches to improve<br />

livelihoods, generate income, or advance conservation. The<br />

objective is to build on a multisectoral analysis of forest<br />

tenure and access without limiting the recognition or<br />

devolution of rights where reform is ongoing.<br />

NOTE 1.4: PROPERTY AND ACCESS RIGHTS 51