Forests Sourcebook - HCV Resource Network

Forests Sourcebook - HCV Resource Network

Forests Sourcebook - HCV Resource Network

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

nity territory into individual plots, which may be attempted<br />

through forest and land use planning exercises, runs the risk<br />

of adversely affecting the livelihoods and social cohesion of<br />

indigenous communities. (See, for example, the Asian<br />

Development Bank-financed poverty assessment for Lao<br />

PDR [State Planning Committee 2000].) Individual tenure<br />

arrangements should be developed with care and only with<br />

the informed participation of the local communities.<br />

Importance of land and long-term resource use<br />

rights. Most Indigenous Peoples see resource use tenure as<br />

essential for their livelihoods and cultural survival. Land<br />

tenure and long-term access to natural resources are<br />

essential for forest-related projects that affect Indigenous<br />

Peoples. Lack of, or insecure, tenure or short-term tenure or<br />

use rights arrangements are likely to prevent positive project<br />

outcomes and intensify degradation of forests. In contrast,<br />

secure land tenure and long-term tenure arrangements are<br />

likely to empower local communities to manage forests in<br />

sustainable ways.<br />

While international law recognizes Indigenous Peoples’<br />

rights to ancestral land and natural resources, and some<br />

countries have begun to recognize these rights in national<br />

law, the situation is far from uniform. Many countries in<br />

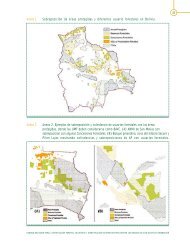

Latin America (for example, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico,<br />

and Nicaragua) and the Philippines have assigned<br />

Indigenous Peoples large territories or enacted legislation<br />

recognizing their rights. Most other countries do not legally<br />

recognize indigenous land and resource use rights, and those<br />

that do, do not always protect such rights in practice. The situation<br />

is compounded by the fact that most indigenous areas<br />

have never been demarcated or titled, or lack documentation<br />

of such official conventions. Accordingly, ancestral lands as<br />

well as areas of current occupation and resource use (if these<br />

differ) are often without legal recognition or protection.<br />

Forest-based projects should support land and long-term<br />

resource use rights of Indigenous Peoples where relevant. In<br />

countries with legislation supporting Indigenous Peoples’ land<br />

and resource use rights, projects should incorporate activities<br />

that formalize and regularize them. Where the customary<br />

lands of Indigenous Peoples are legally under the domain of<br />

the state, or where it is otherwise inappropriate to convert traditional<br />

rights into those of legal ownership, alternative<br />

arrangements should be implemented to grant long-term,<br />

renewable rights of custodianship and use of forest areas to<br />

Indigenous Peoples (see OP 4.10 for more details). Where<br />

Indigenous Peoples are weak relative to private commercial<br />

interests, it may be useful to combine government ownership<br />

of forests with use rights to forest products for Indigenous<br />

Peoples. Such a combination could help to protect Indigenous<br />

Peoples’ interests as well as prevent conversion of forest land to<br />

nonforest uses in the short term. As needed, legal reforms<br />

should also be supported to enhance the recognition of land<br />

and resource use rights of Indigenous Peoples.<br />

Historical and political context to addressing rights.<br />

To address the land and resource use rights of Indigenous<br />

Peoples, it is important to understand the historical and<br />

political context in the country and local area. Indigenous<br />

Peoples have varying cultural values regarding tenure over<br />

forest land and forest products that need to be understood and<br />

addressed in project design. The belief system of some<br />

Indigenous Peoples does not encompass the concept of natural<br />

resource “ownership” at all, which can affect the way they<br />

address customary tenure claims and rights as well as daily<br />

management of resources. Views on individual and collective<br />

tenure also vary. The extent to which tenure rights are linked to<br />

stewardship responsibilities also varies from group to group.<br />

Historical, cultural, and socioeconomic studies combined<br />

with participatory methods and community mapping exercises<br />

can help build a good understanding of local communities,<br />

their cultures, resource use, and customary land and<br />

resource tenure arrangements. They may also help to build<br />

trust and avoid conflicts over land and resource use, provided<br />

that findings are incorporated into project design, including<br />

measures that recognize Indigenous Peoples’ customary<br />

rights and continued access to sustainable resource use.<br />

Use of partnerships for enhancing protection and<br />

sustainability. In the context of CBFM, work with<br />

Indigenous Peoples to enhance efforts to manage forest<br />

resources. Building efforts on current relationships between<br />

the environment and Indigenous Peoples can lead to winwin<br />

situations that enhance the protection of biodiversity<br />

and natural resources and at the same time support the<br />

cultures and sustainable livelihoods of local communities<br />

(see chapter 9, Applying <strong>Forests</strong> Policy OP 4.36, and chapter<br />

12, Applying OP 4.10 on Indigenous Peoples, in section II of<br />

this sourcebook, and note 1.2, Community-Based Forest<br />

Management).<br />

Experience has shown that true partnerships are difficult<br />

to attain for various reasons, such as continued focus on<br />

top-down approaches, conflicting interests, corruption, and<br />

limited capacity. Despite such difficulties, however, collaborative<br />

arrangements are gaining ground quickly because<br />

they can help resolve conflicts, foster learning during implementation,<br />

enhance management of forest resources and<br />

biodiversity, and support the livelihoods and cultures of<br />

44 CHAPTER 1: FORESTS FOR POVERTY REDUCTION