Forests Sourcebook - HCV Resource Network

Forests Sourcebook - HCV Resource Network

Forests Sourcebook - HCV Resource Network

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

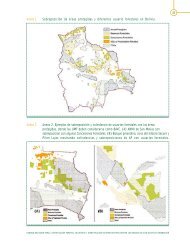

Discussions and proposals on how to set a reference level<br />

have centered around identifying rates of deforestation or<br />

land conversion (historical hectares per year deforested) by<br />

looking at several years of deforestation data (most likely<br />

interpreted from satellite images). The deforestation rates<br />

would then be translated into a greenhouse gas emissions<br />

rate (a reference level). New annual “rates of deforestation”<br />

would be compared against the reference level. A reduction<br />

in the rate of deforestation would, therefore, also translate<br />

into a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, which might<br />

then make the government or entity responsible for getting<br />

emissions reduced eligible for financial compensation.<br />

Countries interested in REDD will need to, among other<br />

things, identify a baseline for carbon emissions and a rate of<br />

forest-cover change. While specific guidance will become<br />

available on determining baselines for forest cover and carbon<br />

emissions, a country will clearly need to be able to set a<br />

target that is based on a reduction from a certain reference<br />

level and quantify how much reduction in deforestation<br />

actually occurred if the government is to get credits. Historical<br />

data and projected deforestation rates will be important<br />

for determining baselines. Appropriately set baselines help<br />

ensure that REDD initiatives are capturing and covering the<br />

costs associated with reduced emissions but not creating<br />

perverse incentives.<br />

National and international reporting obligations.<br />

Countries are obliged to report information related to their<br />

forest sectors to a variety of international and regional conventions,<br />

agreements, and bodies (Braatz 2002). There are<br />

10 international instruments in force relevant to forests. 1<br />

Parties to each of these instruments are asked to report on<br />

measures taken to implement their commitments under<br />

the instrument. In most cases, reporting consists of qualitative<br />

information on activities and means of implementation<br />

(for example, policy, legislative, or institutional measures).<br />

In a few cases, reporting also includes quantitative<br />

biophysical and socioeconomic data on forest resources or<br />

resource use. These reports, and associated efforts to monitor<br />

and assess status and trends in forest resources and progress<br />

in meeting international commitments, help orient national<br />

and international policy deliberations (Braatz 2002).<br />

Accurate and consistent forest information at the global<br />

scale is still needed, specifically information on how much<br />

forest is lost annually and from where. The lack of such<br />

information is partly because previous efforts depended on<br />

inconsistent definitions of forest cover and used methodologies<br />

that could not readily be replicated or were very<br />

expensive and time consuming (see box 7.5).<br />

The concern regarding national reporting burdens has<br />

been acknowledged in international forums for forest dialogue.<br />

Since 2000, various efforts have attempted to harmonize<br />

national reporting on biological diversity (specifically<br />

for CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity), CITES (Convention<br />

on International Traded in Endangered Species),<br />

CMS (Convention on Migratory Species), the Ramsar Convention,<br />

and WHC (World Heritage Convention). In April<br />

2002, CBD, by Decision VI/22, adopted the expanded work<br />

program on forest biological diversity, which included as one<br />

of its activities to “seek ways of streamlining reporting<br />

between the different forest-related processes, in order to<br />

improve the understanding of forest quality change and<br />

improve consistency in reporting on sustainable forest management<br />

(SFM)” (Conference of the Parties [COP] Decision<br />

VI/22). These efforts all require reaching a common understanding<br />

of forest-related concepts, terms, and definitions.<br />

Monitoring framework design. What is being monitored,<br />

how the information will be used and by whom, and<br />

the sustainability of a monitoring system should all inform<br />

its design. Monitoring systems should be designed to be<br />

flexible and able to respond to a dynamic context, which can<br />

change the scope and objective of monitoring. The monitoring<br />

system design must consider the end user and sustainability<br />

of the system. Engagement of end users in the<br />

design and implementation of the system increases their<br />

confidence in the system and ensures its utility.<br />

Measurement framework. A measurement framework is<br />

helpful in designing the monitoring system. A measurement<br />

framework should have goals, criteria (the desirable endpoints),<br />

indicators for each criteria (how well each criteria is<br />

being fulfilled), and approaches (qualitative or quantitative)<br />

for measuring the indicators. The goals and desired outcomes<br />

should guide identification of specific indicators. In<br />

systems that integrate conservation and production, a hierarchy<br />

of goals can be established. Some may be broad, universal<br />

goals and others may be more specific (yet have some<br />

universal applicability).<br />

When choosing a framework, various alternatives that<br />

have been tested and implemented should be considered, as<br />

should new ones. Ideally, preference should be given to the<br />

framework already in use in the country, for example, the<br />

Criteria and Indicators framework used by the nine regional<br />

Criteria and Indicators processes (including the Ministerial<br />

Conference on Protection of <strong>Forests</strong> in Europe), the Driver-<br />

Pressure-State-Impact-Response model, or the Services<br />

Model framework implemented by Millennium Ecosystem<br />

252 CHAPTER 7: MONITORING AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT