Forests Sourcebook - HCV Resource Network

Forests Sourcebook - HCV Resource Network

Forests Sourcebook - HCV Resource Network

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

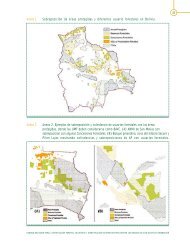

Box 5.6<br />

Participation and Transparency<br />

in Bolivia<br />

To ensure increased transparency in government<br />

decisions, the Public Forest Administration is<br />

empowered to consult with various groups of civil<br />

society. After decentralization and the reorganization<br />

of the forest sector administration, forest<br />

resources decisions are no longer at the exclusive<br />

discretion of bureaucrats, but are instead subject<br />

to public scrutiny and made with public participation.<br />

Thus, open auctions govern the allocation of<br />

all new concession contracts. Open auctions also<br />

rule the sale of confiscated forest products and<br />

equipment. Regulations allow the cancellation of<br />

previously granted rights only with due process,<br />

guaranteeing people’s rights and fostering a balance<br />

between regulators and the regulated. Moreover,<br />

the forest administration must submit<br />

reports to the government twice a year, hold public<br />

hearings once a year to explain work carried<br />

out, and provide an opportunity for the public to<br />

raise questions about performance. Any citizen<br />

can freely request copies of official documents.<br />

Source: Contreras-Hermosilla and Vargas Rios 2002.<br />

responsibilities and commensurate resources and authority<br />

are essential for quality decentralized governance. The problems<br />

faced by the rapid forest decentralization processes in<br />

Indonesia illustrate the importance of achieving a clear distribution<br />

of authority and responsibilities for various forest<br />

management functions (licensing, forest concessions, classification<br />

of forests) between the levels of government and<br />

between governments and civil society and private sector<br />

institutions (Boccucci and Jurgens 2006.<br />

Bureaucratic resistance to change. Decentralization in<br />

India (Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh), Guatemala<br />

(Elias and Wittman 2004), Nicaragua (Larson 2001), and<br />

other countries shows that government executives are generally<br />

opposed to sharing power and resources with lower<br />

levels of government. Even when transfer of certain powers<br />

is mandated by law, in practice this has meant granting<br />

autonomy to manage only the least significant resources,<br />

keeping decisions about the use of the most valuable ones at<br />

higher levels. Furthermore, higher levels of government<br />

commonly have a tendency to maintain control over financial<br />

resources, thus effectively shaping the actions of lower<br />

levels of government or of local communities and other<br />

interest groups that require financial backing. This resistance<br />

to sharing power is one of the most critical threats to<br />

effective forest decentralization. In most cases, tackling this<br />

obstacle entails twin efforts aimed at (i) raising awareness of<br />

government officials based on clear and sound intellectual<br />

discourse and (ii) identification and support of key agents<br />

of change, as in Indonesia. Systems of institutional incentives<br />

must be geared toward rewarding progress in decentralization<br />

processes. This can be facilitated by democratic<br />

decision making schemes that enhance downward accountability<br />

of local government officials to local populations.<br />

(Resistance to change is also addressed in note 5.2, Reforming<br />

Forest Institutions).<br />

Capacity building. Another lesson of experience is that lack<br />

of local capacity is often used as an excuse for reducing the pace<br />

of forest decentralization or for recentralizing. However, local<br />

capacity is unlikely to ever be created unless decentralization<br />

takes place. Thus, implementation of forest decentralization<br />

programs may require education and training programs for<br />

local governments and civil society institutions expected to<br />

play a role in the decentralized management of forest resources<br />

(World Bank 2004). If significant responsibility for forest<br />

resource management is transferred to local institutions, as in<br />

Indonesia, technical assistance will be required. Planning such<br />

assistance will require an institutional analysis of demands and<br />

capacities of the various levels of government and a coherent<br />

plan to fill in gaps. Improving the knowledge base and managerial<br />

capacity are long-term undertakings that may require<br />

sustained support for extended periods. As emphasized by a<br />

project in Nicaragua, World Bank interventions should pilot<br />

decentralization initiatives and be designed as a series of sequential<br />

building blocks as institutional and managerial capacity<br />

gradually develops over long periods (World Bank 1998).<br />

SELECTED READINGS<br />

Manor, J. 1999. The Political Economy of Democratic Decentralization.<br />

Washington, DC: World Bank.<br />

Kaimowitz, D., C. Vallejos, P. Pacheco, and R. Lopez. 1998.<br />

“Municipal Governments and Forest Management in<br />

Lowland Bolivia.” Journal of Environment and Development<br />

7 (1): 45–59.<br />

Larson, A., P. Pacheco, F. Toni, and M. Vallejo. 2006.<br />

Exclusión e Inclusión en la Forestería Latinoamericana.<br />

¿Hacia Dónde va la Decentralización? La Paz, Bolivia:<br />

CIFOR/IDRC.<br />

Ribot, J. C. 2002. “Democratic Decentralization of Natural<br />

<strong>Resource</strong>s. Institutionalising Popular Participation.”<br />

World <strong>Resource</strong>s Institute, Washington, DC.<br />

164 CHAPTER 5: IMPROVING FOREST GOVERNANCE