United Nations Human Rights Council - Harvard Model United Nations

United Nations Human Rights Council - Harvard Model United Nations

United Nations Human Rights Council - Harvard Model United Nations

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong><br />

<strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

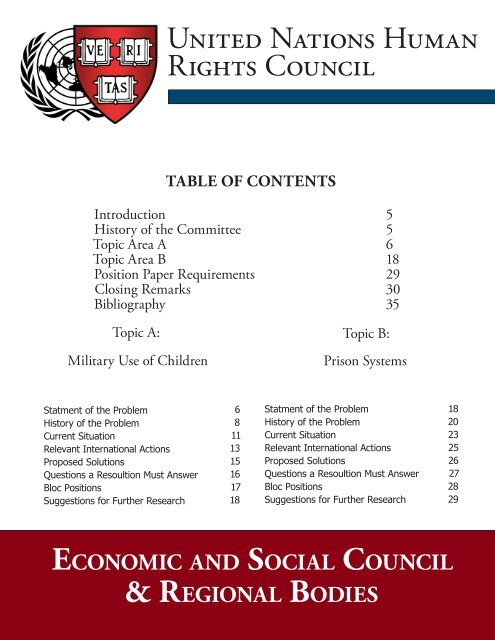

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Introduction 5<br />

History of the Committee 5<br />

Topic Area A 6<br />

Topic Area B 18<br />

Position Paper Requirements 29<br />

Closing Remarks 30<br />

Bibliography 35<br />

Topic A:<br />

Topic B:<br />

Military Use of Children<br />

Prison Systems<br />

Statment of the Problem<br />

History of the Problem<br />

Current Situation<br />

Relevant International Actions<br />

Proposed Solutions<br />

Questions a Resoultion Must Answer<br />

Bloc Positions<br />

Suggestions for Further Research<br />

6<br />

8<br />

11<br />

13<br />

15<br />

16<br />

17<br />

18<br />

Statment of the Problem<br />

History of the Problem<br />

Current Situation<br />

Relevant International Actions<br />

Proposed Solutions<br />

Questions a Resoultion Must Answer<br />

Bloc Positions<br />

Suggestions for Further Research<br />

18<br />

20<br />

23<br />

25<br />

26<br />

27<br />

28<br />

29<br />

Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong><br />

& Regional Bodies

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

<strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> 2012<br />

A Letter From the Secretary General<br />

Dear Delegates,<br />

Hunter M. Richard<br />

Secretary-General<br />

Stephanie N. Oviedo<br />

Director-General<br />

Ana Choi<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Administration<br />

Ainsley Faux<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Business<br />

Alexandra M. Harsacky<br />

Comptroller<br />

Sofia Hou<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Innovation and Technology<br />

Juliana Cherston<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

General Assembly<br />

Ethan Lyle<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong><br />

Charlene S. Wong<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Specialized Agencies<br />

I could not be more honored to welcome you to the fifty-ninth session of <strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>Model</strong><br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong>. Our entire staff of 205 <strong>Harvard</strong> undergraduates is eager to join with you<br />

this January at the Sheraton Boston for an exciting weekend of debate, diplomacy, and<br />

cultural exchange. You and your 3,000 fellow delegates join a long legacy of individuals<br />

passionate about international affairs and about the pressing issues confronting our World.<br />

Founded in 1927 as <strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>Model</strong> League of <strong>Nations</strong>, our organization has evolved<br />

into one of America’s oldest, largest, and most international <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> simulations.<br />

Drawing from this rich history, <strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> has strived to emphasize<br />

and promote the unique impact of the UN and its mandates in the eradication of<br />

humanity’s greatest problems. Despite its difficulties and often-unfortunate image in the<br />

press, the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> is truly a global body with representation of 193-member states<br />

and is the closest the World has ever achieved to a “Parliament of Man.”<br />

At HMUN, we strive to recreate this body and the international environment it fosters<br />

through our emphasis on welcoming more and more international delegations to our<br />

conference each year. For the fifty-ninth session, HMUN is proud to welcome delegations<br />

from over 35 countries to share their experiences with others from across the World. Not<br />

only can you debate global issues in committee, but also discuss the China-US relations<br />

with a delegate hailing from Shanghai or EU economic policy with a delegate from<br />

Germany. I encourage you to go above and beyond research and discussions within your<br />

committee to learn from your fellow delegates.<br />

In this guide, you are about to embark on a valuable intellectual endeavor. Your committee<br />

director has worked tirelessly to research and compile this extensive background guide.<br />

Please use it as a foundation in your own research for committee and to contribute to<br />

your debates and final resolutions. I wish you the best of luck in your preparation and in<br />

committee this January.<br />

Sincerely,<br />

59 Shepard Street, Box 205<br />

Cambridge, MA 02138<br />

Voice: (617)-398-0772<br />

Fax: (617) 588-0285<br />

Email: info@harvardmun.org<br />

www.harvardmun.org<br />

Hunter Richard<br />

Secretary-General<br />

<strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong><br />

secgen@harvardmun.org<br />

22 Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> Specialized & Regional Agencies Bodies

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

<strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> 2012<br />

Dear Delegates of the Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> & Regional Bodies,<br />

It is my distinct honor and high privilege to welcome you to the Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> &<br />

Regional Bodies organ of <strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>United</strong> Nation’s 59th session.<br />

Hunter M. Richard<br />

Secretary-General<br />

Stephanie N. Oviedo<br />

Director-General<br />

Ana Choi<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Administration<br />

Ainsley Faux<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Business<br />

Alexandra M. Harsacky<br />

Comptroller<br />

Sofia Hou<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Innovation and Technology<br />

Juliana Cherston<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

General Assembly<br />

Ethan Lyle<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong><br />

Charlene S. Wong<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Specialized Agencies<br />

The Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> occupies a unique position within the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong>’ history.<br />

While questions of security were of primary concern at the time when the UN Charter was drafted,<br />

the final version set out a critical role for ECOSOC. World leaders in 1945, it seems, understood<br />

that global peace absolutely requires social stability and economic growth in order to truly last. This<br />

daunting mission carries on into the present day for the Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong>. At HMUN,<br />

our organ also incorporates a collection of Regional Bodies that bring more localized debates to the<br />

forefront. These committees are entrusted with the critical task of exploring regional dialogues on a<br />

wide array of issues for which larger and more generalized UN bodies simply cannot do justice to.<br />

Our organ for HMUN 2012 is ambitious in its scope: our committees will jump from the League<br />

of <strong>Nations</strong> in pre-World War II Europe to the dawn of the year 2100 and the complex problems it<br />

will bring. Our organ is diverse not only in time, but also in topics, with modern day discussions<br />

on human rights, development, and many pressing regional issues. This session, we will even set out<br />

to incorporate the unique contributions of Non-Governmental Organizations into the Economic<br />

and Social <strong>Council</strong> & Regional Bodies organ, with the hope that they bring a fresh perspective to<br />

our substantive discussions.<br />

I could not be more excited to invite you to join us in January for what will most certainly be an<br />

amazing experience. The members of staff for our organ this year are some of the most intelligent<br />

and dedicated individuals I have ever met. They have been working tirelessly for months and will<br />

continue to make preparations as we quickly approach January 26th, 2012. I am confident you will<br />

come to appreciate them greatly, just as I have learned to in my time with them thus far. I know<br />

the Assistant Directors, Moderators, and committee Directors cannot wait to meet each and every<br />

one of you!<br />

At <strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong>, we set out to tackle meaningful issues that world leaders have<br />

struggled mightily to resolve. Our challenge is considerable. And yet, HMUN 2012 will be one<br />

of the fondest memories we will come to share. Meeting friends—old and new—hailing from<br />

different cities, states, and continents is a profound experience. I wish you the best of luck in your<br />

preparations for HMUN, and please do not hesitate to contact me with any questions or concerns<br />

you may have along the way. Opening Ceremonies will be here before you know it. Get ready.<br />

Sincerely,<br />

59 Shepard Street, Box 205<br />

Cambridge, MA 02138<br />

Voice: (617)-398-0772<br />

Fax: (617) 588-0285<br />

Email: info@harvardmun.org<br />

www.harvardmun.org<br />

Ethan Lyle<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> & Regional Bodies<br />

ecosoc@harvardmun.org<br />

Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> & Regional Bodies<br />

3

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

<strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> 2012<br />

Dear Delegates,<br />

Hunter M. Richard<br />

Secretary-General<br />

Stephanie N. Oviedo<br />

Director-General<br />

Ana Choi<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Administration<br />

Ainsley Faux<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Business<br />

Alexandra M. Harsacky<br />

Comptroller<br />

Sofia Hou<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Innovation and Technology<br />

Juliana Cherston<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

General Assembly<br />

Ethan Lyle<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong><br />

Charlene S. Wong<br />

Under-Secretary-General<br />

Specialized Agencies<br />

Welcome to Boston and the 59th session of <strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong>! My name is Lisa<br />

Wang, and I will be your director for the <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong>. Growing up in East Brunswick,<br />

NJ, I began <strong>Model</strong> UN and Congress conferences in high school, taking on roles from Antonin<br />

Scalia in the Supreme Court, to the <strong>United</strong> States in the Security <strong>Council</strong>, to Count Vincent<br />

Benedetti in the 19th century French Cabinet. The experiences inspired me to select my current<br />

concentration, Government—a mixture unique to <strong>Harvard</strong> of international relations, political<br />

science, economics, and social science. I am also seeking a secondary field in Ethnic Studies, which<br />

incorporates migration, race, and human rights issues.<br />

Aside from HMUN, I also chaired the Security <strong>Council</strong> at <strong>Model</strong> Security <strong>Council</strong>, an introductory<br />

conference held for freshmen in the fall. In March, I will be traveling to Vancouver, Canada to<br />

chair INTERPOL at WorldMUN, one of <strong>Harvard</strong>’s college <strong>Model</strong> UN conferences. I also direct<br />

the Constitutional Convention at <strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>Model</strong> Congress and tutor Boston-area immigrants in<br />

preparation for the U.S. Citizenship exam. Outside of class, I work as a research assistant, take<br />

dance classes, and try to explore as much of Boston as possible.<br />

For four days, we will be simulating the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong> in discussion<br />

of two vital topics affecting every nation on the globe: the military use of children and prisoners’<br />

rights. Though I have been interested in both topics since serving in our high school chapter of<br />

Amnesty International, my experience this past summer interning at the Legal Aid Society of<br />

New York City has truly brought these topics to a head. Assisting attorneys representing juvenile<br />

delinquents as well as children suffering abuse and neglect by their parents, I was exposed to the<br />

inherent need to protect children and adults from being exploited not only as victims in a stateless<br />

society but also as criminals subject wholly to a state’s jurisdiction. Though HRC typically takes a<br />

proactive and rights-based approach to these issues, it is important, especially on the latter issue, to<br />

evaluate the countering needs for societal protection, economic efficiency, and justice into account<br />

to the greatest extent possible, while still advocating and protecting children’s and prisoners’ rights<br />

on an international level.<br />

While approaching these topics with the necessary finesse and prudence will be challenging, I have<br />

confidence that this session will be able to resolve several unanswered questions on both fronts by<br />

collaborating across blocs and incorporating the solutions and ideas of as many players as possible.<br />

Best of luck during your research and preparation process! I hope this guide will be useful to get<br />

you versed in the basics of both topics. In the meantime, do not hesitate to contact me with any<br />

questions or to introduce yourselves!<br />

Warmest regards,<br />

59 Shepard Street, Box 205<br />

Cambridge, MA 02138<br />

Voice: (617)-398-0772<br />

Fax: (617) 588-0285<br />

Email: info@harvardmun.org<br />

www.harvardmun.org<br />

Lisa Wang<br />

Director, <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

hrc@harvardmun.org<br />

44 Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> Specialized & Regional Agencies Bodies

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Topic A: The Military Use of Children<br />

Amnesty International reports that 350,000 children<br />

under the age of eighteen are serving in direct combat<br />

action. In over twenty countries, more than 1.1 million<br />

children under the age of fifteen are used as porters, sex<br />

slaves, guards, spies and land mine testers. Robbed of an<br />

education and thus the hope for a better future, these<br />

children grow into adults that perpetuate the cycle of<br />

violence in war-torn countries. Gripped in a society of<br />

perpetual conflict, the only adults that they can trust to<br />

provide food, water, and shelter are military, paramilitary,<br />

and guerilla soldiers. They are often forced to kill their<br />

family members and commit devastating atrocities such<br />

as forced labor, rape, and torture. Clearly, the physical,<br />

psychological, and social damage can be insurmountable.<br />

While this is certainly a pressing security issue, it is above<br />

all a moral one. The UN Convention on the <strong>Rights</strong><br />

of the Child explicitly bans the use of child soldiers<br />

but this practice continues to be rampant. The abuse<br />

of these children’s rights needs to be addressed by the<br />

international community immediately in the light of a<br />

growing number of international civil conflicts in the<br />

post-Cold War era.<br />

Topic B: Prison Systems<br />

Despite being frequently relegated to domestic<br />

jurisdiction, the human rights abuses of civil and<br />

military prisoners warrants international discussion on<br />

the types of treatment acceptable under various human<br />

rights protocols (including the Universal Declaration<br />

of <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong>; the International Covenant on Civil<br />

and Political <strong>Rights</strong>; and the Convention against Torture<br />

and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment<br />

or Punishment). In prisons, jails, juvenile facilities, and<br />

immigration detention centers around the world, brutal<br />

practices are observed in the name of national security<br />

and the “common good.” Recent accusations of torture<br />

have been directed at countries as varied as the <strong>United</strong><br />

States, France, Afghanistan, China, Angola, Israel,<br />

and Brazil (to name a few). Several questions can be<br />

addressed under this topic. Broadly, what has been the<br />

historical development of international prisoners’ rights?<br />

Is it an appropriate time now for an international bill of<br />

prisoners’ rights? If so, states should be prepared to address<br />

the following specific questions: How should pregnant<br />

women be treated while imprisoned? What should the<br />

voting rights of ex-prisoners be and who should determine<br />

them? Should immigrants in detention have access to the<br />

same kinds of rights as prisoners (e.g. access to lawyers)?<br />

What is a fair way to implement petitions and reviews for<br />

parole? What should be the global consensus on capital<br />

punishment, in particular for subgroups such as juvenile<br />

delinquents, mentally disabled prisoners, the elderly, and<br />

pregnant women? In the end, the main theme of this<br />

discussion is: “Should we develop an international code<br />

of standard for prison treatment? Is this expression of<br />

human rights feasible and/or needed at an international<br />

level?” And where do we draw the tenuous line between<br />

human dignity and international security?<br />

HISTORY OF THE COMMITTEE<br />

From the ashes of World War II, the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong><br />

was created in 1945 to provide a platform for dialogue<br />

between countries in order to prevent future wars. A<br />

year later, the UN Commission for <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong><br />

(UNCHR) was formed under the Economic and Social<br />

<strong>Council</strong> and given the task of promoting and protecting<br />

human rights around the world. In 2006, the General<br />

Assembly voted overwhelmingly to replace UNCHR<br />

with the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

(UNHRC) through resolution A/RES/60/251, as<br />

UNCHR was heavily criticized for allowing countries<br />

with poor human rights records to become members.<br />

To prevent the same criticism, UNHRC members can<br />

now be removed by the General Assembly (on a 2/3<br />

vote) for “gross and systemic” violations of human rights.<br />

UNHRC is an inter-governmental subsidiary body of<br />

the General Assembly comprising 47 member states<br />

with three-year terms, working closely with the Office of<br />

the High Commissioner for <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> (OHCHR)<br />

to strengthen the promotion and protection of human<br />

rights around the world. One year after holding its first<br />

meeting in Geneva, Switzerland, UNHRC bolstered its<br />

mandate by adopting an institution building-package<br />

with three key elements:<br />

Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> & Regional Bodies<br />

5

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

The Universal Periodic Review (UPR), during<br />

which each of the UN’s 192 member nations will<br />

receive human rights reviews by an HRC Working<br />

Group once every four years, based on reports<br />

from the nation, the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong>, and any<br />

relevant stakeholders such as non-governmental<br />

organizations (NGOs);<br />

An Advisory Committee that serves as UNHRC’s<br />

think tank, producing expertise and advice on<br />

thematic human rights issues;<br />

A Complaints Procedure that allows individuals and<br />

organizations to bring accounts of human rights<br />

violation to the attention of the <strong>Council</strong>, which<br />

will then be collated into reports on gross and<br />

reliably attested violations of human rights and<br />

fundamental freedoms for the <strong>Council</strong> to review.<br />

Aside from performing reviews of nations’ human<br />

rights statuses and receiving complaints from individuals<br />

and organizations, UNHRC also issues resolutions on<br />

human rights violations around the globe. It has been<br />

heavily criticized by the <strong>United</strong> States and various UN<br />

Secretaries General for over-emphasizing Israel’s human<br />

rights violations in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. As of<br />

now, Israel is the only state to have been condemned by<br />

the HRC, which has voted to make an annual review<br />

of Israel’s alleged human rights abuses a permanent<br />

fixture of the <strong>Council</strong>. UNHRC can also establish High-<br />

Level Commissions of Inquiry to probe allegations of<br />

systematic human rights abuse. It did just that for the<br />

2006 Lebanon conflict, establishing an Inquiry into<br />

Israel’s human rights abuses.<br />

Despite the conflict and political finger-pointing,<br />

UNHRC has been successful in many areas of human<br />

rights protection in the past. It has adopted resolutions<br />

in opposition to the “defamation of religion,” as well<br />

as expressed concerns in the linkage between human<br />

rights and climate change through Resolution 10/4.<br />

HRC has sent fact-finding missions to places such as<br />

Cambodia, Angola, and Cuba to find out about human<br />

rights situations on the ground and report back to the<br />

<strong>Council</strong>. It has established Working Groups in the lesserdiscussed<br />

areas of enforced disappearance, indigenous<br />

peoples, right to development, arbitrary detention, and<br />

the use of mercenaries, among others, to delve deeper<br />

into unaccounted issues that nevertheless deserve<br />

international attention and mitigation.<br />

TOPIC A: THE MILITARY USE<br />

OF CHILDREN<br />

Statement of the Problem<br />

Child soldiers are defined by the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong><br />

Children’s Fund (UNICEF) as boys and girls under the<br />

age of 18 who become part of a regular or irregular armed<br />

force or group in any capacity 1 —whether in combat<br />

or support roles. Throughout the world, thousands of<br />

children are used as frontline combatants, saboteurs,<br />

porters, human shields, sex slaves, spies, carriers, “wives,”<br />

cooks, and land-mine testers in arguably the worst<br />

perversion of child labor. 2<br />

In the last decade of warfare, more than two million<br />

children have been killed, a rate of more than 500 a<br />

day, or one every three minutes. 3 Of these two million<br />

deaths, tens of thousands are caused directly by fighting<br />

from bullets, bombs, landmines, machetes, knives,<br />

grenades, and other weapons. 4 Over the same period<br />

of time, half a million children from 87 countries have<br />

been recruited by government forces or armed groups, 5<br />

resulting in significant numbers of child soldiers across<br />

every continent with the exception of Antarctica. 6 Every<br />

year, 300,000 children are coerced or induced to take up<br />

arms for various causes, ranging from civil war, rebellion,<br />

revolt, and insurrection to bandit or guerilla warfare. 7<br />

This number has grown significantly from 200,000 in<br />

1988. 8 Child soldiers are currently serving in over 36<br />

major wars. 9 Another 8,000-10,000 die annually because<br />

of landmines. 10 According to statistics from a situation<br />

update report submitted by Pawan Bimali and Bishnu<br />

Pathak to the Conflict Study Center in 2009, 80% of<br />

conflicts involving child soldiers include combatants<br />

under the age of 15, with some as young as seven or eight,<br />

and 40% of all child soldiers are girls. 11<br />

With the breakdown of many cultural barriers<br />

opposing the use of child soldiers, such victims are<br />

now found globally, with particular prevalence in the<br />

regions of Africa, Asia, and Latin America; they are<br />

also now emerging in the Middle East. 12 As recently as<br />

2005, reports surfaced that the Taliban were using up<br />

to 8,000 children in armed conflict in Afghanistan. 13<br />

Approximately 120,000 of the 300,000 child soldiers<br />

are found in Africa, followed by the Asia-Pacific region<br />

at a distant second with 75,000. Additionally, Africa<br />

has the highest rate of growth in child soldier usage. 14<br />

66 Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> Specialized & Regional Agencies Bodies

Though much of existing literature implies that the<br />

explosion in non-state actor recruitment of child soldiers<br />

is responsible for the dramatic increase in victims,<br />

state recruitment remains high in several conflicts. For<br />

example, the Sudanese civil war of 1993-2002 started<br />

with child soldier use between rebel and government<br />

forces at a ratio of 64:36 respectively, but ended with a<br />

ratio of 24:76. 15<br />

The geographic and historical prevalence of child<br />

soldier usage can be explained by the various advantages<br />

these young combatants confer on a state or non-state<br />

armed group. Compared to adults, children are much<br />

easier to capture, train, and handle. 16 With the advent<br />

and proliferation of small arms, technological barriers<br />

to operation of weaponry by children were removed.<br />

Small weapons are light and cheap—weighing as little<br />

as seven pounds and costing roughly US$6—and are<br />

also easily assembled, loaded, and fired; they can be<br />

used by children as young as ten years old. 17 Children<br />

are also valuable as “cannon fodder,” sent to distract or<br />

divert the enemy when weapons are low. 18 Both state and<br />

non-state actors require strict obedience and discipline<br />

from their soldiers. Young, impressionable, and eager to<br />

please, children are often attractive recruits because of<br />

their loyalty. 19 Children are also more readily available<br />

for unpaid service via easy capture, as well as harder<br />

to spot and kill by the enemy. Some commanders also<br />

believe they are more efficient fighters, benefiting from<br />

the hesitancy shown by enemies who are unsure or<br />

unwilling to harm children in the opposition. 20 For these<br />

reasons, child soldiers are frequently coerced, abducted,<br />

or forcibly recruited into service.<br />

On the other hand, many child soldiers are pulled<br />

into military service and are compelled to volunteer for<br />

a variety of reasons, including political beliefs, religious<br />

obligations, family affiliations, and survival. In a time<br />

of conflict and war, families may offer their children as<br />

soldiers in order to gain physical and economic security.<br />

Or, children orphaned by the war or its accompanying<br />

diseases may enlist just to have a steady source of food,<br />

clothing, and shelter. Children may also join an armed<br />

military group due to peer pressure or an urge to avenge<br />

abuses and atrocities they themselves have experienced<br />

during civil conflict. 21 Traditionally, a majority of children<br />

enlisting for political or religious reasons fall into nonstate<br />

groups, while those seeking economic security will<br />

tend to enlist in state armies. 22<br />

Regardless of whether the child was forced or<br />

volunteered, military service is a violation of children’s<br />

Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> & Regional Bodies<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

rights as outlined in several international documents.<br />

Article 38 of the UN Convention on the <strong>Rights</strong> of the<br />

Child (CRC) obligates State parties to “take all feasible<br />

measures to ensure that persons who have not attained the<br />

age of fifteen years do not take a direct part in hostilities”<br />

and to “ensure protection and care of children who are<br />

affected by armed conflict.” Article 39 further requires<br />

State Parties to promote recovery and reintegration<br />

of children affected by armed conflict. 23 In addition,<br />

the Convention requires State parties to take effective<br />

measures to abolish social practices that are prejudicial<br />

to children’s health, which as the UN argues, would<br />

“necessarily include practices that put children in harm’s<br />

way in the context of armed conflict.” The 1998 Rome<br />

Statue of the International Criminal Court classifies the<br />

use of children under 15 by armed groups in intentional<br />

attacks as war crimes. 24 All these documents agree that<br />

the core rights of the child include the right to education,<br />

play and recreation, and love and care. Even if they are<br />

trained and indoctrinated by their armed recruiters,<br />

these children do not experience a holistic education that<br />

allows them to become sufficiently prepared to make<br />

their own decisions in life. An armed existence not only<br />

necessarily robs them of their right to recreation but also<br />

affects their view on their own rights to relaxation and<br />

leisure later on in life. Often physically separated from<br />

their families, child soldiers are stripped of their right to<br />

familial love and care. 25<br />

Not only does armed conflict violate children’s<br />

rights, but it also severely impacts children physically,<br />

psychologically, and socially. War has a vastly more<br />

detrimental impact on children than on adults, as it<br />

strips away the traditional protection of family, society,<br />

and law that children rely on during peacetime. 26 The<br />

physical drains in a child soldier’s life include: taxing<br />

and strenuous activities such as carrying heavy objects<br />

and traveling far distances; exposure to harsh conditions<br />

and the elements; hunger; and lack of sleep and rest. 27<br />

Meanwhile, psychological stresses from family separation,<br />

military involvement, becoming wounded, witnessing<br />

deaths, torture, and constant worry have long-lasting<br />

consequences. As child soldiers, living in a dangerous and<br />

suspenseful environment induces much stress on mental<br />

health, causing former child soldiers to report episodes<br />

of paranoia that still afflict them long after their days on<br />

the battlefield are over. 28 Reports of former child soldiers<br />

suffering from alcoholism, emotional disturbance, and<br />

criminality are not uncommon. 29 Further symptoms<br />

range from introversion and isolation to depression,<br />

7

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

headaches, and phobias. 30 When children are forced<br />

to train in preparation for a kill, they tend to become<br />

more antagonized and emotionally distraught than their<br />

adult counterparts. 31 These psychological symptoms are<br />

compounded by poverty and create far more serious,<br />

long-lasting consequences on the child’s overall mental<br />

health than those a child experiencing regular Post-<br />

Traumatic Stress Disorder in a western context would<br />

encounter. 32 The life of a child soldier is also particularly<br />

difficult for girls, who often suffer from horrendous<br />

crimes like rape and sexual assault, in addition to<br />

menstruation in unsanitary conditions, limited freedom<br />

of movement, and disproportionate physical demands<br />

from adults that tend to ignore their gender. They are<br />

generally assigned more non-combative duties and have<br />

less ability to advance through the military ranks than<br />

their male counterparts. 33<br />

The military use of children afflicts an entire society<br />

by perpetuating violence and hindering development. It<br />

has long been understood that socialization of violence in<br />

youth creates a generation of violent adults that perpetuate<br />

the instability in a nation. 34 Loss of childhood innocence<br />

and education as well as the horrific experience of being<br />

forced from their homes and into combat cut deep into<br />

children’s psyche. The results of this can be loss of trust,<br />

aggressive behavior, and tendency toward revenge, which<br />

can manifest in another cycle of violence. 35 Exposure to<br />

violence and experience with firearms severely shifts the<br />

psychological make-up of child soldiers from children<br />

raised under a less harsh social environment. 36 Once a<br />

nation’s children have learned to accept violence as a<br />

fact of life and comfortably use firearms for security and<br />

power, the foundations of a violent society have been laid<br />

and will be difficult to eradicate.<br />

History of the Problem<br />

EARLY EXAMPLES<br />

The earliest examples of the military use of children<br />

go back to the wars of antiquity. Children living in the<br />

Mediterranean basin were frequently employed as aides,<br />

charioteers, and armor bearers. Their use was detailed in<br />

the Bible, Egyptian Art, and Greek Mythology. Though<br />

Ancient Roman practice forbade the use of youths under<br />

age 16, young boys were still often found on the battlefield<br />

in various conquests in the Roman Kingdom, which<br />

lasted from 753 to 509 BC. The Spartans of Ancient<br />

Greece, as a very militarized society prominent from 546<br />

to 371 BC, separated boys from their families to undergo<br />

military training at the age of seven. Centuries later,<br />

medieval Europe in the 1200s and 1300s continued these<br />

earlier practices by hiring thousands of boys as young as<br />

twelve to become “squires.” Though these youths rarely<br />

saw combat action, they tragically were sold into slavery<br />

when wars abated. 37<br />

19 TH CENTURY<br />

The 19 th century witnessed a more systematic<br />

recruitment, training, and indoctrination of youths<br />

by various military leaders to advance their ambitions.<br />

French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte practiced routine<br />

and systematic recruiting of boys around age fifteen<br />

during the early 1800s. Napoleon’s armies swelled with<br />

youths as young as twelve, and the young navy cadets<br />

were called “powder monkeys.” 38 Similarly, in 1827, Tsar<br />

Nicholas II of Russia put forth an annual conscription<br />

quota for Jewish males aged 12-25, requiring them to<br />

serve for 25 years. Recruits under the age of 18 were placed<br />

into special training as “Cantonists” until 18, when they<br />

were considered battle-ready. After being dispatched to<br />

the battalions where they would receive training, many<br />

would die en route due to torture or starvation. While<br />

training them, Tsar Nicholas II took care to indoctrinate<br />

the surviving young Jewish boys and forcibly baptized<br />

them in the “Russian” religion, or Orthodox Christianity,<br />

to ensure their loyalty. 39<br />

Other examples of 19 th century child soldier use<br />

did not stem from ambitious dictators, but rather the<br />

legitimate desire to defend or maintain one’s homeland.<br />

In 1861, US President Abraham Lincoln allowed<br />

soldiers under age 18 to enlist in the Union Army<br />

during the American Civil War. During its attempted<br />

unification in the early 19 th century, Nepal did not<br />

have any systematically organized state armed forces<br />

in the battlefields. Overwhelmed by the huge and<br />

well-equipped British army, all local people (including<br />

children, women, and the elderly) in war zones served as<br />

irregular battalions in the defense of Nepal.<br />

20 TH CENTURY<br />

The practice of child soldiering skyrocketed in the<br />

20 th century. The most memorable example of child<br />

soldier usage in the past century was the Hitler Jugend<br />

(Youth) in the closing days of World War II (1939-1945),<br />

where 1,000 children aged 10-18 were responsible for<br />

combat and various support services. Remnants of the<br />

organization at the close of the war were mowed down by<br />

Russian forces, though the survivors were not prosecuted<br />

by the international community. 40 During China’s<br />

88 Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> Specialized & Regional Agencies Bodies

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

Global Distribution of Child Soldier Use (Source: Radda Barnen for Sweedish Save the Children; <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> Watch)<br />

Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), Mao Ze Dong utilized<br />

children for revolutionary purposes. Red Guards aged<br />

eight to fifteen were responsible for the most heinous<br />

acts, including the capture, torture, and murder of adult<br />

civilians deemed “enemies of the revolution.” In addition,<br />

African independence movements were accomplished<br />

with the aid of child soldiers. In particular, Angola and<br />

Mozambique enlisted several children in the 1970s to<br />

achieve colonial independence. 41<br />

Since the end of the Cold War, a rise in intrastate<br />

conflict has resulted in warfare impacting children<br />

in unprecedented ways. 42 Many young teens fought<br />

in the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) in the war for<br />

independence against the Serbs in 1997-98. Many<br />

children went on to join other Albanian rebel groups,<br />

serving in both the Liberation Army of Presevo and<br />

the Albanian National Liberation Army. 43 The Lord’s<br />

Resistance Army (LRA) of Uganda—a sectarian religious<br />

and military group operating in northern Uganda—<br />

frequently abducts children from villages and forces<br />

them into conscription to engage in armed rebellion<br />

against the national government. 44 Reports from former<br />

child soldiers reveal shocking living conditions, sexual<br />

exploitation, and general squalidness. 45<br />

The civil war in Sierra Leone lasted from 1991-2001<br />

and resulted in the forced recruitment of 15,000-22,000<br />

children from their villages, who were then funneled<br />

into military conscription; about half were between the<br />

ages of 8 and 14. 46 The few that voluntarily joined rebel<br />

forces spoke frequently of the need to seek revenge for<br />

lost parents or environmental destruction; those who<br />

joined government forces spoke of honor and defense<br />

of their homeland. 47 Many were obliged into sexual<br />

slavery or taking alcohol and drugs. After the conflict<br />

abated, short-term Disarmament, Demobilization, and<br />

Reintegration (DDR) programs were implemented, but<br />

long-term problems in education still persist and need<br />

to be addressed. 48 Additionally, Sierra Leone’s fractured<br />

family system due to the war would require ex-child<br />

combatants to reintegrate into society without a “home”<br />

or a “family” to return to. 49<br />

The Sudanese civil war was also fraught with the<br />

forced recruitment of child soldiers by both government<br />

forces and the Sudan People Liberation Army (SPLA).<br />

Government forces, in addition to training youth in<br />

only 14 days to prepare them for combat on the front<br />

lines, engaged in the practice of selling child slaves from<br />

marginalized areas in the southern part of Sudan. 50 Many<br />

of these Sudanese child soldiers are orphaned and elected<br />

to join in the fighting to satisfy their basic needs and to<br />

avenge the deaths of their parents, who were often killed<br />

in front of them by the enemy. 51<br />

Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> & Regional Bodies<br />

9

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

INTERNATIONAL ATTEMPTS TO MITIGATE<br />

CHILD SOLDIER USE<br />

The Geneva Conventions of 1949 were the first step<br />

towards the protection of civilians and other special<br />

groups during times of armed conflict. The original<br />

Geneva Convention had four Parts; in particular, Part III<br />

described the special category of “protected persons” in<br />

time of war, though the definition of “children” varies. 52<br />

In 1977, the two additional Protocols to the original<br />

four Conventions were drafted. Protocol I applied to the<br />

protection of victims of international armed conflicts,<br />

reaffirming the original Geneva Convention while<br />

clarifying certain provisions based on developments in<br />

modern international warfare. Protocol II applied to<br />

victims of internal armed conflict, taking the original<br />

Convention beyond the quite limiting scope of wars<br />

of “international character,” as conflicts were originally<br />

defined. Specifically, Article 77 states that all Parties shall<br />

“take all feasible measures in order that children who have<br />

not attained the age of 15 years do not take a direct part<br />

in hostilities.” Additionally, if a child is captured in war,<br />

“they shall continue to benefit from the special protection<br />

accorded by this Article.” 53<br />

In the 1980s, children became increasingly<br />

victimized by armed conflict, and thus, legislation that<br />

dealt explicitly with the problem became necessary. The<br />

UN Convention on the <strong>Rights</strong> of the Child (CRC)<br />

makes children’s best interest a primary consideration for<br />

all government bodies. An almost universally accepted<br />

human rights instrument, the CRC is ratified by all<br />

states except for the <strong>United</strong> States and Somalia. Its most<br />

relevant article to the case of the military use of children<br />

is article 38(2) which reads: “States Parties shall take all<br />

feasible measures to ensure that persons who have not<br />

attained the age of 15 years do not take a direct part<br />

in hostilities.” 54 Many states have taken this provision<br />

further by ratifying the convention under the proviso<br />

that the mandatory minimum age should be 18. 55<br />

In 1998, significant advances were achieved when<br />

the International Criminal Court declared that the use of<br />

children under 15 in military conflict a war crime under<br />

its Rome Statute. 56 In this treaty, the delegates agree to<br />

prohibit not only children’s direct participation in warfare,<br />

but also their active participation in military activities<br />

such as sabotage, reconnaissance, spying and the use of<br />

children as decoys, messengers, or at security (military)<br />

checkpoints. It also prohibits the use of children in direct<br />

support of efforts to carry supplies to the front line and<br />

defines sexual slavery as a crime against humanity. 57 A<br />

year later, the International Labour Organization Worst<br />

Forms of Child Labour Convention (1999) prohibited<br />

forced or compulsory recruitment of children under 18<br />

for use in combat. 58 Article 3(a) defines the worst forms<br />

of child labor as “all forms of slavery or practices similar<br />

to slavery, such as the sale and trafficking of children,<br />

debt bondage and serfdom and forced or compulsory<br />

labor, including forced or compulsory recruitment of<br />

children for use in armed conflict.” 59 The African Union<br />

followed suit with its African Charter on the <strong>Rights</strong> and<br />

Welfare of the Child (1999), which prohibits recruitment<br />

or participation in direct hostilities of anyone under 18. 60<br />

It is the only regional treaty in the world that deals with<br />

the issue of child soldiers. 61<br />

With the turn of the century, even greater efforts were<br />

channeled by international bodies and states to address<br />

this increasingly visible issue. In 2000, the International<br />

Conference on War Affected Children: From Words<br />

to Action, was held in Winnipeg, Canada—a powerful<br />

gathering of interested individuals, relevant organizations,<br />

and former child soldiers that resulted in several strong<br />

outcomes. Subsequently, the Optional Protocol to the<br />

CRC on the use of child volunteers by state actors (2000)<br />

was drafted. It sets the minimum age for compulsory<br />

recruitment or direct participation in hostilities at 18;<br />

calls upon States parties to raise the age for voluntary<br />

recruitment and to provide special protections and<br />

safeguards for those under 18; categorically prohibits<br />

armed groups from recruiting or using in hostilities<br />

anyone under 18; and calls upon States parties to<br />

provide technical cooperation and financial assistance<br />

to help prevent child recruitment and deployment, and<br />

to improve the rehabilitation and social reintegration of<br />

former child soldiers. 62<br />

Additionally, there are several movements led by<br />

non-governmental organizations (NGO) and the general<br />

public aimed at pressuring international bodies and states<br />

to act upon the existing legal framework for protecting<br />

children’s rights. Red Hand Day (February 12 th ) is an<br />

annual commemoration day for current and former<br />

child soldiers. The Coalition to Stop the Use of Child<br />

Soldiers and other organizations frequently organize mass<br />

demonstration activities, such as a walk to symbolize the<br />

distance child soldiers walk daily, or a 25-hour silence to<br />

mark the 25 th year of the Uganda conflict. 63 Increasingly,<br />

these movements are driven by youth, for youth, and<br />

champion former child soldiers as their spokespersons<br />

and advocates.<br />

10 Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> Specialized & Regional Agencies Bodies

Current Situation<br />

TRENDS AND THEMES<br />

Present-day usage of child soldiers is marked by several<br />

global themes, the first of which is the commodification<br />

of the use of child soldiers and its implications for wartorn<br />

countries gripped by violence. Increasingly, there is a<br />

connection between government inadequacy and neglect<br />

and the rise in child soldiering. Studies have noted that<br />

non-state armed groups are starting to offer a semblance<br />

of government by providing basic social services such<br />

as health, education, dispute settlement, and a sense of<br />

protection in areas where the government has failed to<br />

meet with its obligations to its citizens by to provide labor,<br />

housing, food, and education. 64 As a result, children in<br />

war-torn countries ironically turn to non-governmental<br />

armed groups for some form of stability and routine in<br />

their lives.<br />

The 21 st century has also seen strong connections<br />

between the use of child soldiers, the availability of<br />

education, and the level of development in many<br />

nations. In April, 2000, the World Education Forum<br />

identified the conflicts of the 1990s in particular as<br />

major obstacles to the Millennium Development Goal<br />

of providing universal primary education. 65 As scholars<br />

Guy Goodwin-Gill and Ilene Cohn suggest, the act of<br />

voluntary child participation in armed conflict is caused<br />

by poverty, which—enhanced by war—incites families<br />

to enlist their children as combatants to reap the benefits<br />

of looting. 66 A survey of 300 demobilized child soldiers<br />

in the Democratic Republic of Congo revealed that 61%<br />

came from families with no income and more than half<br />

had at least six siblings. 67 In a 2002 study of Filipino<br />

child soldiers by Rufa Cagoco-Guiam, an overwhelming<br />

majority of child soldier respondents came from poor,<br />

economically marginalized communities whose parents<br />

were also involved in armed groups. 68 Though other<br />

scholars do not see such a clear-cut connection between<br />

poverty rates and numbers of child soldiers, it is certain<br />

that states that do not suffer from poverty rarely use child<br />

soldiers. 69<br />

Another emerging trend that gives cause for great<br />

worry is the general acceptance of child soldiering as a<br />

demographic need or a cultural practice. More and more,<br />

the disturbing phenomenon of the acceptance of child<br />

soldiering in Africa as a cultural tradition has emerged,<br />

an outgrowth of the theory of cultural relativism—the<br />

idea that an individual’s activities (such as the use or<br />

recruitment of child soldiers) should be understood in<br />

Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> & Regional Bodies<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

the context of his or her culture. 70 This argument is also<br />

emerging in the Muslim context. According to Islamic<br />

belief, childhood stops at the onset of puberty (14 or 15<br />

years old). At this time, followers are expected to observe<br />

and exercise Islamic teachings—including heeding the<br />

call of holy war. 71 Most of the international human rights<br />

doctrines that guarantee children’s welfare also pertain to<br />

the right to culture, so how does one reconcile conflicting<br />

rights and obligations? In addition, proponents of child<br />

soldiering use the social argument of age structure to<br />

claim that in areas where life spans are shorter, children<br />

graduate to the population’s typical range of adulthood<br />

much sooner and thus become eligible for military<br />

service. Under this claim, it would be unfair to expect a<br />

nation in a time of military attack to be disadvantaged<br />

because it can draw on only a smaller subset of its adult<br />

population for its infantry. 72<br />

The appropriate response to such claims of cultural<br />

relativism lies in two sources of universalism: science and<br />

international human rights law. Scientific studies have<br />

outlined a universal timeline of neurological development<br />

for the human child; no matter what culture, religion,<br />

or background, most children have the same level of<br />

development and maturity at every age point—a fact that<br />

makes a standard minimum age for adulthood based on<br />

scientific measures of mental development appropriate.<br />

As for the question of whether the right to culture or<br />

children’s rights are to be respected, the UN Convention<br />

on the <strong>Rights</strong> of the Child encodes the idea that a child’s<br />

interests are to be given paramount consideration. The<br />

African Union echoed this sentiment by prohibiting<br />

cultural practices that might be prejudicial to a child’s<br />

health or life in its Charter on Children’s <strong>Rights</strong>. 73<br />

Another trend is the prevalence of terrorism and<br />

the ensuing use of children in terrorist activities, which<br />

creates tension between the universal protection of<br />

children and the need to respect cultural practices—<br />

both of which are valuable UN ideals. In Palestine, for<br />

example, Hamas proclaims youth suicide bombers in a<br />

way that wins families enormous respect, and so children<br />

frequently voluntarily join suicide missions. 74 Under<br />

Saddam Hussein’s tyrannical rule, children aged 10-15<br />

underwent intensive three-week military training to<br />

prepare for suicide missions. 75 This issue merits careful<br />

consideration by the <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong> as to<br />

whether or not different standards should be set for child<br />

terrorists vs. child soldiers (see case study #1).<br />

11

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

Case Study #1: Guantanamo Bay 76<br />

Trained and disciplined by his father since the<br />

age of 10 to believe in Al Qaeda doctrine, Omar<br />

Khadr joined the organization at the age of 15 and<br />

was sent directly into battle. On July 27, 2002,<br />

U.S. forces launched an attack on a suspected<br />

compound where Khadr was staying. Though<br />

shot three times, Khadr, still alive, was captured<br />

by U.S. forces and brought to Guantanamo Bay.<br />

Seven years later, at the age of 22, Omar has<br />

yet to leave the camp. Nearly blind from the<br />

shrapnel and disabled from his wounds, he has<br />

been interrogated or tortured for information for<br />

a third of his life.<br />

Did the U.S. government violate any international<br />

treaties or protocols by capturing a fifteen year<br />

old prisoner of war?<br />

During interrogation, Omar confessed to<br />

throwing a grenade that killed one U.S. officer<br />

and injured two others. Should these statements<br />

be used against him? If so, in what type of court<br />

system, and with what sorts of protection?<br />

enlisted below the age of 18. In Armies of the Young:<br />

Child Soldiers in War and Terrorism, David M. Rosen<br />

takes a different stance. He criticizes humanitarian<br />

organizations for viewing child soldiers merely as victims.<br />

Instead, he argues, children have their own moral<br />

agency, as demonstrated in case studies of Nazi Germany<br />

and modern day Uganda, when children refused to<br />

be recruited. He uses this to disclaim the automatic<br />

assumption of childhood innocence in child soldier cases,<br />

implying that there is some level of guilt that must be<br />

taken into account. 77<br />

Others make the abstract argument that “children’s<br />

rights” in their current westernized, liberal understanding<br />

are geared toward assuming self-consciousness and<br />

autonomy, which inherently implies that children are<br />

viewed as rational beings capable of moral reasoning.<br />

As such, their guilt is no less than an adult’s when they<br />

choose to join a military and commit violent acts. 78 In<br />

other words, if children are entitled to the same rights<br />

as adults, fair justice and the spirit of equality would<br />

demand that children be held accountable and metered<br />

the same punishments as adults. Opposing scholars<br />

rebut that rights and justice are as much about dialogue,<br />

dependence, and welfare as they are about individualistic<br />

autonomy and reason, and as such, an impartial justice<br />

must recognize and protect a special sphere for children. 79<br />

(See case study #2).<br />

In his affidavit, Omar Khadir named several<br />

instances of torture perpetrated against him<br />

by officials at Guantanamo Bay. Should these<br />

officials be held accountable? If so, at what level<br />

of government and under what international/<br />

national laws? If not, why?<br />

THE QUESTION OF POST-CONFLICT GUILT<br />

The question of post-conflict guilt among child<br />

soldiers is answered by different people in various<br />

ways based on the specific circumstances of the child’s<br />

involvement with armed groups. For example, was the<br />

child forced into recruitment or did he volunteer for<br />

service? If he was forced, what alternative options were<br />

available, and how feasible were they? Did he work under<br />

state or non-state actors? How old is the child? What type<br />

of crime was committed? Traditionally, international<br />

courts have supported the absolutist legal doctrine that<br />

no matter the circumstances, children cannot be found<br />

guilty of any acts they committed during wartime if they<br />

Case Study #2: Uganda 80<br />

February 2004: Heavily armed guerillas from<br />

the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) struck<br />

Barnlooyo camp in a weekend attack, massacring<br />

192 villagers in what officials called one of the<br />

bloodiest atrocities of northern Uganda’s war.<br />

Using mortars and assault rifles, rebels set huts<br />

ablaze with hundreds of residents trapped inside.<br />

Father Sebhat Ayele, a Catholic missionary<br />

from Eritrea, said: “I saw one hut with seven<br />

family members still burning and three people<br />

in the next hut were also burning.” Many of the<br />

rebels, 90% of whom were under the age of 18,<br />

were subsequently captured and killed by the<br />

governmental Ugandan People’s Defense Force<br />

(UPDF).<br />

What was your initial reaction upon reading<br />

about the attack? Did this change when you<br />

12 Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> Specialized & Regional Agencies Bodies

discovered that many of the rebels were children?<br />

If so, how?<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

Did the government violate any international<br />

laws or treaties by capturing and killing the child<br />

soldiers?<br />

If so, where does the justice lie for the 192 victims<br />

of these atrocities?<br />

DISARMAMENT, DEMOBILIZATION,<br />

REHABILITATION, & REINTEGRATION (DDRR)<br />

The question of what to do with former child soldiers<br />

is also fraught with uncertainties and complications.<br />

Traditionally, nations have utilized a Disarmament,<br />

Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) model.<br />

Disarmament strips combatants of their weapons;<br />

Demobilization constitutes the assembly, registration,<br />

and transportation en masse of former child soldiers in<br />

preparation for a return to civilian life; and Reintegration<br />

means social and economic assimilation of former child<br />

soldiers into civilian life. 81 For the purposes of our<br />

discussion, we will take a more comprehensive approach<br />

to DDR advocated by certain scholars, by including a<br />

second “R”, Rehabilitation—the restoration to good<br />

condition using therapy or education.<br />

For their DDRR programs, countries have tried<br />

measures such as amnesty, cash incentives for the<br />

surrender of firearms, livelihood assistance, counseling,<br />

scholarships, and technical training. 82 A general rule for a<br />

comprehensive DDRR program is the inclusion of seven<br />

elements:<br />

Community sensitization<br />

Formal disarmament/demobilization and transition<br />

Tracing and family mediation<br />

Return to family and community with follow up<br />

Ongoing access to health care<br />

Traditional cleansing ceremonies<br />

Schools or skill training. 83<br />

However, gaps in DDRR programs remain due to<br />

fragmented government focus on the program, lack of<br />

child soldier involvement, non-compliance by local<br />

government agencies, and a lack of collaboration and<br />

communication between parties. 84<br />

Child Soldier Tasks and Duties (Source: American Federation<br />

of Teachers)<br />

An issue this committee needs to address is the<br />

inadvertent exclusion of girls from many DDRR programs<br />

because of their classification as non-combatants, which<br />

causes many of them to be re-recruited. 85 Because girls<br />

do not serve in direct combat as often as boys, they do<br />

not qualify for many types of DDRR programs, and yet<br />

their trauma is just as damaging. Additionally, interim<br />

care centers for children transitioning from military<br />

service proved dangerous for girls, as they were housed<br />

with boys that were still learning to control their violent<br />

tendencies. 86 Because girls are often saddled with the<br />

burden of children born in wartime and tend to have<br />

greater psychosocial needs than boys, many sites simply<br />

turn them away because they are not equipped with<br />

child-care or mental health services. 87 In addition, as the<br />

case of Liberian ex-child soldiers demonstrates, disabled<br />

ex-combatants form an additional neglected subgroup<br />

that needs more attention in the overall DDRR process. 88<br />

Many DDRR programs are simply not equipped with the<br />

materials or experience to work with children suffering<br />

from advanced psychiatric or physical disabilities because<br />

of their involvement in conflict.<br />

Relevant International Actions<br />

After a groundbreaking report on child soldiers was<br />

released by Graça Machel in 1996, the UN General<br />

Assembly recommended in 1997 an appointment<br />

of a Special Representative to the Secretary-General<br />

for Children and Armed Conflict. Former Secretary-<br />

General Kofi Annan appointed Olara A. Otunnu to the<br />

position. 89 The Special Representative works with the<br />

Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> & Regional Bodies<br />

13

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

Differing Population Age Structures in Developed v. Developing Countries Affects Child Soldier Usage and Raises the<br />

Argument for State-by-State Minimum Ages for Military Recruitment (Source: <strong>United</strong> States Census)<br />

Security <strong>Council</strong>, HRC, General Assembly, member<br />

states, NGOs, and the public to create policy on the<br />

prevention and DDRR of child soldier usage.<br />

The 1989 Convention on the <strong>Rights</strong> of the Child<br />

was strengthened in 2000 with the Optional Protocol<br />

on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict,<br />

the product of six years of debate in working groups<br />

established by the UN Commission on <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong>.<br />

The Protocol raises the age for military conscription to<br />

18 and requires states parties to take all feasible measures<br />

to ensure that state forces and nongovernmental armed<br />

groups do not recruit or use persons below 18. It also<br />

promotes international cooperation and assistance in the<br />

rehabilitation and reintegration of former child soldiers. 90<br />

Today, the Protocols are independent from each other<br />

and the CRC, meaning that any state can ratify the<br />

Convention, Protocol I, or Protocol II independently.<br />

In 1997, UNICEF published its Cape Town<br />

Principles and Best Practices on the Recruitment of<br />

Children into the Armed Forces and on Demobilization<br />

and Social Reintegration of Child Soldiers in Africa. A<br />

decade later, A/HRC/RES/11/1 (2009) was passed by<br />

14 Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> Specialized & Regional Agencies Bodies

the HRC, establishing an Open-ended Working Group<br />

to explore the possibility of elaborating an optional<br />

protocol to the Convention on the <strong>Rights</strong> of the Child to<br />

create a reporting procedure. During troop withdrawal<br />

from various international conflicts, UN-negotiated<br />

action plans provided for the demobilization of children<br />

in Uganda (2009) and Afghanistan (2011).<br />

The UN Security <strong>Council</strong> also elaborated on the use of<br />

child soldiers in its Resolutions 1261, 1265, 1296, 1314,<br />

1379, 1460, 1539, 1612. In particular, 1261 (1999),<br />

1265 (1999), and 1296 (2000) deal with the protection<br />

of civilians in armed conflict and have also emphasized<br />

children’s particular vulnerability and need for special<br />

protection. 91 Stressing that children should be a main<br />

priority in the international community, the Security<br />

<strong>Council</strong> also exhorted member states in its resolutions to<br />

incorporate children in any comprehensive strategy for<br />

conflict resolution. 92 Additionally, the Security <strong>Council</strong><br />

goes further to enumerate six grave violations against<br />

children during wartime, and apply these as a basis to<br />

protect children in future conflicts using the appropriate<br />

monitoring and reporting mechanisms:<br />

The killing or maiming of children;<br />

Recruitment or use of child soldiers;<br />

Rape and other forms of sexual violence against<br />

children;<br />

Abduction of children;<br />

Attacks against schools or hospitals; and<br />

Denial of humanitarian access to children. 93<br />

The Department of Peacekeeping Operations,<br />

a body operating under the Security <strong>Council</strong>, is<br />

heavily involved in demobilization of child soldiers in<br />

nearly every peacekeeping mission. For example, the<br />

peacekeeping operation in the Democratic Republic of<br />

Congo, MONUC, works actively with both rebel forces<br />

and the national government to implement existing<br />

demobilization plans, with a particular focus on women<br />

and children. 94<br />

As for recent resolutions, the <strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> High<br />

Commissioner of <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> has established an<br />

Open-ended Working Group to explore the possibility<br />

of allowing communication for the Convention on the<br />

<strong>Rights</strong> of the Child, a process by which individuals can<br />

allege to the HRC that their rights have been violated<br />

under such a convention. Currently, the HRC allows<br />

communication for five human rights treaty bodies. The<br />

Working Group is currently drafting an optional protocol<br />

Economic and Social <strong>Council</strong> & Regional Bodies<br />

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

to the CRC to see if such a procedure can be established.<br />

During its most recent session, the Working Group came<br />

out with a draft proposal—but not without leaving some<br />

unresolved issues:<br />

How should the HRC classify children when they<br />

come before the <strong>Council</strong>—mere dependents or<br />

rights-holding and dignified human beings, or<br />

some mixture of the two?<br />

How do we ensure that the remedies to children’s<br />

suffering under the CRC are directed to the<br />

child and not to his/her representative, parent, or<br />

national government?<br />

Should the child be allowed to express his/her<br />

experience, needs, and expected remedies or should<br />

the best interest of the child be taken foremost into<br />

account? How much weight does the child’s age<br />

and maturity bear into determining the appropriate<br />

approach? 95<br />

Despite its many advances in the protection of<br />

children from armed conflict, much remains to be done<br />

by this session of the HRC.<br />

Proposed Solutions<br />

In peacekeeping operations, monitoring activities,<br />

and UN field operations, child soldiers could be treated<br />

as a distinct and prioritized concern, and agents could<br />

be specially trained in children’s needs. The HRC can<br />

also encourage state and non-state dissidents undergoing<br />

peace talks or negotiations to consider the role of child<br />

soldiers and offer suggestions for DDRR.<br />

To improve DDRR efforts, the international<br />

community has the option of emphasizing the<br />

diversion of resources to the maintenance of education<br />

and psychosocial community initiatives during and<br />

after conflict. This could include a social campaign to<br />

emphasize the benefits of education to children in childheaded<br />

households. During DDRR, there could be more<br />

effective family tracing initiatives to assist internally<br />

displaced children, accompanied with necessary therapy<br />

and counseling to ease the transition to family life.<br />

The HRC and other relevant UN bodies such as<br />

UNICEF could launch and spread a campaign to support<br />

adoption and adherence to the Optional Protocol to the<br />

Convention on the <strong>Rights</strong> of the Child, which raises the<br />

age of recruitment and participation in armed forces to<br />

18.<br />

15

<strong>United</strong> <strong>Nations</strong> <strong>Human</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

On the other hand, many have lamented the myriad<br />

obstacles to holding states accountable for child soldier<br />

use. They argue instead for the imposition of criminal<br />

liability on those who use child soldiers via a provision<br />

of the ICC charter or a regional charter. There have been<br />

some successes in this arena in recent years. The ICC<br />

has issued war crimes for the use of children in armed<br />

combat to armed groups in the Democratic Republic<br />

of Congo (DRC) and Uganda. Additionally, truth<br />

commissions of Sierra Leone, Timor-Leste, and Liberia<br />

have all addressed the issue of child soldiers. 96 Individuals<br />

such as the DRC’s Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, Liberia’s<br />

Charles Taylor, Uganda’s Joseph Kony, and Sierra Leone’s<br />

Alex Tamba Brima are just a few individuals that have<br />

been indicted or sentenced by international courts for<br />

war crimes that include the recruitment and use of<br />

child soldiers. 97 The commissions (for instance the truth<br />

and reconciliation commissions, state restructuring<br />

commission, disappearances investigation commission,<br />

etc.) can be built up in the post conflict period to ensure<br />

social integration for sustainable peace and development.<br />

In efforts to prevent the forced and voluntary<br />

recruitment of child soldiers, special attention should<br />

be given to the social circumstances that exacerbate the<br />

use of child soldiers, including arms transfers, the use<br />

of landmines, and lack of education/healthcare. This can<br />

be done through public awareness events on all scales.<br />

Countries should be encouraged by the UN to withhold<br />

unilateral military assistance to countries that employ<br />

child soldiers.<br />

Less popular or well-accepted solutions have<br />

been proposed. Though they are lauded by some and<br />

dismissed by others, they are worth further exploration<br />

in committee session. This includes the formation of an<br />

international enforcement mechanism for treaties such<br />

as the Convention on the <strong>Rights</strong> of the Child, involving<br />

annual reviews of states and punishments in terms of<br />

fines, sanctions, or removal from human rights bodies<br />

for sustained abuses.<br />

Most importantly, giving children a voice—and<br />

listening to them—will allow children to have a say in<br />

their own protection and in the life of their community<br />

and country. This includes finding nongovernmental<br />

organizations willing to provide free advocacy to former<br />

child soldiers on an individual or class-level basis. 98<br />

Questions a Resolution Must Answer (QARMA)<br />

BASIS FOR INTERNATIONAL CHILDREN’S<br />

RIGHTS<br />

How do earlier human rights documents, especially<br />

those detailing children’s rights, apply in the issue of<br />

the military use of children?<br />

Are children entitled to special rights and protections<br />

because of their age? If so, what are they and why?<br />

Who is responsible for these protections – the state,<br />

the parents, or society at large? If not, on what basis<br />

and with what kinds of implications?<br />

LEGAL ISSUES<br />

Should there be an international standard minimum<br />

age for combat action and/or military support? If so,<br />

at what age should it be? If not, at what level should<br />

the minimum age be established if at all?<br />