Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

IN THE ALBERT<br />

Where the Truth Lies:<br />

Memoir and Memory<br />

By Neena Arndt<br />

“How often do we tell our own life<br />

story? How often do we adjust, embellish,<br />

make sly cuts? And the longer life<br />

goes on, the fewer are those around to<br />

challenge our account, to remind us<br />

that our life is not our life, merely the<br />

story we have told about our life. Told to<br />

others, but—mainly—to ourselves.”<br />

–Julian Barnes, The Sense of an Ending<br />

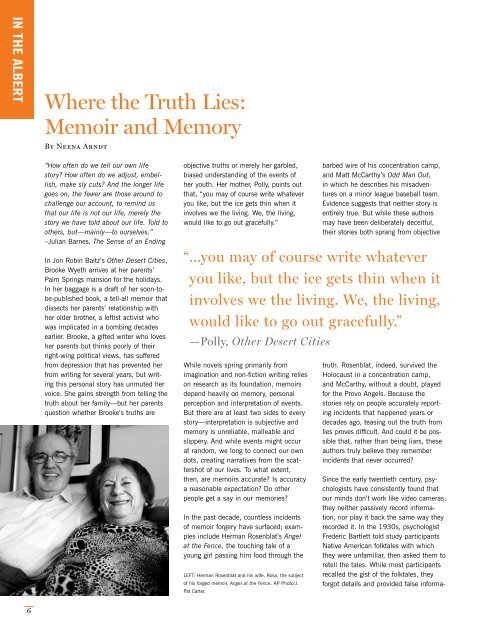

In Jon Robin Baitz’s Other Desert Cities,<br />

Brooke Wyeth arrives at her parents’<br />

Palm Springs mansion for the holidays.<br />

In her baggage is a draft of her soon-tobe-published<br />

book, a tell-all memoir that<br />

dissects her parents’ relationship with<br />

her older brother, a leftist activist who<br />

was implicated in a bombing decades<br />

earlier. Brooke, a gifted writer who loves<br />

her parents but thinks poorly of their<br />

right-wing political views, has suffered<br />

from depression that has prevented her<br />

from writing for several years, but writing<br />

this personal story has unmuted her<br />

voice. She gains strength from telling the<br />

truth about her family—but her parents<br />

question whether Brooke’s truths are<br />

objective truths or merely her garbled,<br />

biased understanding of the events of<br />

her youth. Her mother, Polly, points out<br />

that, “you may of course write whatever<br />

you like, but the ice gets thin when it<br />

involves we the living. We, the living,<br />

would like to go out gracefully.”<br />

While novels spring primarily from<br />

imagination and non-fiction writing relies<br />

on research as its foundation, memoirs<br />

depend heavily on memory, personal<br />

perception and interpretation of events.<br />

But there are at least two sides to every<br />

story—interpretation is subjective and<br />

memory is unreliable, malleable and<br />

slippery. And while events might occur<br />

at random, we long to connect our own<br />

dots, creating narratives from the scattershot<br />

of our lives. To what extent,<br />

then, are memoirs accurate? Is accuracy<br />

a reasonable expectation? Do other<br />

people get a say in our memories?<br />

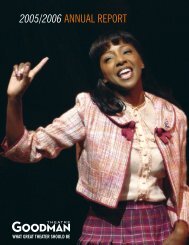

In the past decade, countless incidents<br />

of memoir forgery have surfaced; examples<br />

include Herman Rosenblat’s Angel<br />

at the Fence, the touching tale of a<br />

young girl passing him food through the<br />

barbed wire of his concentration camp,<br />

and Matt McCarthy’s Odd Man Out,<br />

in which he describes his misadventures<br />

on a minor league baseball team.<br />

Evidence suggests that neither story is<br />

entirely true. But while these authors<br />

may have been deliberately deceitful,<br />

their stories both sprang from objective<br />

“...you may of course write whatever<br />

you like, but the ice gets thin when it<br />

involves we the living. We, the living,<br />

would like to go out gracefully.”<br />

—Polly, Other Desert Cities<br />

LEFT: Herman Rosenblat and his wife, Rosa, the subject<br />

of his forged memoir, Angel at the Fence. AP Photo/J.<br />

Pat Carter.<br />

truth. Rosenblat, indeed, survived the<br />

Holocaust in a concentration camp,<br />

and McCarthy, without a doubt, played<br />

for the Provo Angels. Because the<br />

stories rely on people accurately reporting<br />

incidents that happened years or<br />

decades ago, teasing out the truth from<br />

lies proves difficult. And could it be possible<br />

that, rather than being liars, these<br />

authors truly believe they remember<br />

incidents that never occurred?<br />

Since the early twentieth century, psychologists<br />

have consistently found that<br />

our minds don’t work like video cameras;<br />

they neither passively record information,<br />

nor play it back the same way they<br />

recorded it. In the 1930s, psychologist<br />

Frederic Bartlett told study participants<br />

Native American folktales with which<br />

they were unfamiliar, then asked them to<br />

retell the tales. While most participants<br />

recalled the gist of the folktales, they<br />

forgot details and provided false informa-<br />

6