OnStage - Goodman Theatre

OnStage - Goodman Theatre OnStage - Goodman Theatre

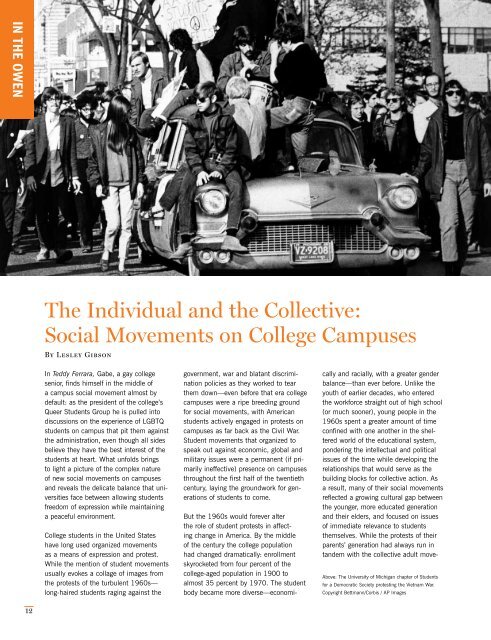

IN THE OWEN The Individual and the Collective: Social Movements on College Campuses By Lesley Gibson In Teddy Ferrara, Gabe, a gay college senior, finds himself in the middle of a campus social movement almost by default: as the president of the college’s Queer Students Group he is pulled into discussions on the experience of LGBTQ students on campus that pit them against the administration, even though all sides believe they have the best interest of the students at heart. What unfolds brings to light a picture of the complex nature of new social movements on campuses and reveals the delicate balance that universities face between allowing students freedom of expression while maintaining a peaceful environment. College students in the United States have long used organized movements as a means of expression and protest. While the mention of student movements usually evokes a collage of images from the protests of the turbulent 1960s— long-haired students raging against the government, war and blatant discrimination policies as they worked to tear them down—even before that era college campuses were a ripe breeding ground for social movements, with American students actively engaged in protests on campuses as far back as the Civil War. Student movements that organized to speak out against economic, global and military issues were a permanent (if primarily ineffective) presence on campuses throughout the first half of the twentieth century, laying the groundwork for generations of students to come. But the 1960s would forever alter the role of student protests in affecting change in America. By the middle of the century the college population had changed dramatically: enrollment skyrocketed from four percent of the college-aged population in 1900 to almost 35 percent by 1970. The student body became more diverse—economically and racially, with a greater gender balance—than ever before. Unlike the youth of earlier decades, who entered the workforce straight out of high school (or much sooner), young people in the 1960s spent a greater amount of time confined with one another in the sheltered world of the educational system, pondering the intellectual and political issues of the time while developing the relationships that would serve as the building blocks for collective action. As a result, many of their social movements reflected a growing cultural gap between the younger, more educated generation and their elders, and focused on issues of immediate relevance to students themselves. While the protests of their parents’ generation had always run in tandem with the collective adult move- Above: The University of Michigan chapter of Students for a Democratic Society protesting the Vietnam War. Copyright Bettmann/Corbis / AP Images 12

The young are particularly likely to be drawn into a movement that represents an unconventional or unexplored aspect of their identity, and these types of social identity movements thrive on college campuses where self-discovery and freedom of expression are paramount. ments of their time, like advocating for workers’ rights, students in the 1960s fought for reform both in public policies that affected their generation, as well as issues relevant to campus life: they spoke out against the Vietnam War and its toll on their generation and pushed back against restrictions on personal freedom (particularly for women) and civil liberties imposed by institutions that saw it as their responsibility to provide students with moral guidance as well as an education. The student movements of the 1960s achieved mixed results, but they successfully established student protests as a permanent tool with which to achieve social and political change. And after the turbulent protests of the 1960s retreated into the history books, a whole new type of social movement begin to take over college campuses. While student movements through the end of the 1960s tended to focus on achieving specific changes within an institution—whether it be a university or the government—the new social movements that have emerged in later decades focus primarily on cultural issues and advocate for change within a society. These movements are typically built around a single broad theme, and strive to create a cultural environment that embraces the values and individuals that these groups represent, with the greater goal of achieving mainstream acceptance of a marginalized group or fringe issue. Often they form on behalf of a group of individuals with a shared common identity, like feminists or LGBTQ individuals, and work to alter the perception of that demographic both within the greater culture and within individual group members themselves. In such movements the goal is threefold: to clearly define the identity of their members on their own terms; to create an environment in which individuals can thrive as their most authentic, uninhibited selves; and to advocate for mainstream acceptance of new or unconventional lifestyles. Since the intention is to change the culture within a community rather than at an institutional level, new social movements are often built through grassroots micromobilization, with recruitment dependent on social networks and informal existing relationships among individuals of the group in question. Usually movements form spontaneously through the convergence of individuals with a common identity, and establish solidarity as individual members’ own sense of identity develops in tandem with the group identity as the collective struggles to boldly accept itself and define “who we are” as a group within a society. Often, the movements are so closely tied to the public identity of a demographic that participation is assumed, as Debra Friedman and Doug McAdam outline in their essay “Collective Identity and Activism: Networks, Choices, and the Life of a Social Movement”: “Most movements do not arise because isolated individuals choose to join the struggle. Rather, established groups redefine group membership to include commitment to the movement as one of its obligations; the threatened loss of member status is usually sufficient to produce high rates of participation. As a result, the movement is largely spared the need to provide selective incentives to attract participants.” The young are particularly likely to be drawn into a movement that represents an unconventional or unexplored aspect of their identity, and these types of social identity movements thrive on college campuses where self-discovery and freedom of expression are paramount. And although most universities aim to encourage self-discovery in students, social movements on campuses have always experienced push-back from administrators as the balance between allowing free speech and permitting destructive or distracting behavior on campus is continually in negotiation. Some universities implement “speech codes” that define the terms under which an institution permits various forms of demonstration and protest. While these codes are created as a well-intended tool to limit conflict and violence on campus, a 2011 study by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education found that up to 65 percent of the colleges had inadvertently created policies that violated the Constitution’s protection of free speech. (Public universities are prohibited from limiting nondestructive free speech, while private institutions are granted more freedom with their speech codes.) And while students are free to organize and demonstrate as they choose, often even peaceful movements come into conflict with contemporary university administrations hesitant to draw attention to any degree of discontent on campus. New Work Fast Fact Between 2004 and 2011, the Goodman’s New Stages series offered staged readings of 45 new plays. Of these, 34—including Teddy Ferrara—have gone on to full productions at the Goodman or elsewhere to date. Goodman Theatre would like to thank all New Work donors for their help in making this program possible. 13

- Page 1 and 2: January - March 2013 The Personal a

- Page 3 and 4: IN THE ALBERT From the Artistic Dir

- Page 5 and 6: not permit me to do: to write about

- Page 7 and 8: LEFT: Rachel Griffiths and Thomas S

- Page 9 and 10: RIGHT: Dr. Elizabeth Loftus deliver

- Page 11 and 12: IN THE OWEN A Conversation with Chr

- Page 13: ABOVE: Michael Goldsmith and Grant

- Page 17 and 18: AT THE GOODMAN Coming This Spring:

- Page 19 and 20: IN THE WINGS GeNarrations: Stories

- Page 21 and 22: Cocktails and Conversation On Octob

- Page 23 and 24: Center Stage Above: Cherie and Ken

IN THE OWEN<br />

The Individual and the Collective:<br />

Social Movements on College Campuses<br />

By Lesley Gibson<br />

In Teddy Ferrara, Gabe, a gay college<br />

senior, finds himself in the middle of<br />

a campus social movement almost by<br />

default: as the president of the college’s<br />

Queer Students Group he is pulled into<br />

discussions on the experience of LGBTQ<br />

students on campus that pit them against<br />

the administration, even though all sides<br />

believe they have the best interest of the<br />

students at heart. What unfolds brings<br />

to light a picture of the complex nature<br />

of new social movements on campuses<br />

and reveals the delicate balance that universities<br />

face between allowing students<br />

freedom of expression while maintaining<br />

a peaceful environment.<br />

College students in the United States<br />

have long used organized movements<br />

as a means of expression and protest.<br />

While the mention of student movements<br />

usually evokes a collage of images from<br />

the protests of the turbulent 1960s—<br />

long-haired students raging against the<br />

government, war and blatant discrimination<br />

policies as they worked to tear<br />

them down—even before that era college<br />

campuses were a ripe breeding ground<br />

for social movements, with American<br />

students actively engaged in protests on<br />

campuses as far back as the Civil War.<br />

Student movements that organized to<br />

speak out against economic, global and<br />

military issues were a permanent (if primarily<br />

ineffective) presence on campuses<br />

throughout the first half of the twentieth<br />

century, laying the groundwork for generations<br />

of students to come.<br />

But the 1960s would forever alter<br />

the role of student protests in affecting<br />

change in America. By the middle<br />

of the century the college population<br />

had changed dramatically: enrollment<br />

skyrocketed from four percent of the<br />

college-aged population in 1900 to<br />

almost 35 percent by 1970. The student<br />

body became more diverse—economically<br />

and racially, with a greater gender<br />

balance—than ever before. Unlike the<br />

youth of earlier decades, who entered<br />

the workforce straight out of high school<br />

(or much sooner), young people in the<br />

1960s spent a greater amount of time<br />

confined with one another in the sheltered<br />

world of the educational system,<br />

pondering the intellectual and political<br />

issues of the time while developing the<br />

relationships that would serve as the<br />

building blocks for collective action. As<br />

a result, many of their social movements<br />

reflected a growing cultural gap between<br />

the younger, more educated generation<br />

and their elders, and focused on issues<br />

of immediate relevance to students<br />

themselves. While the protests of their<br />

parents’ generation had always run in<br />

tandem with the collective adult move-<br />

Above: The University of Michigan chapter of Students<br />

for a Democratic Society protesting the Vietnam War.<br />

Copyright Bettmann/Corbis / AP Images<br />

12