the kenai brown bear population on - U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

the kenai brown bear population on - U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

the kenai brown bear population on - U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

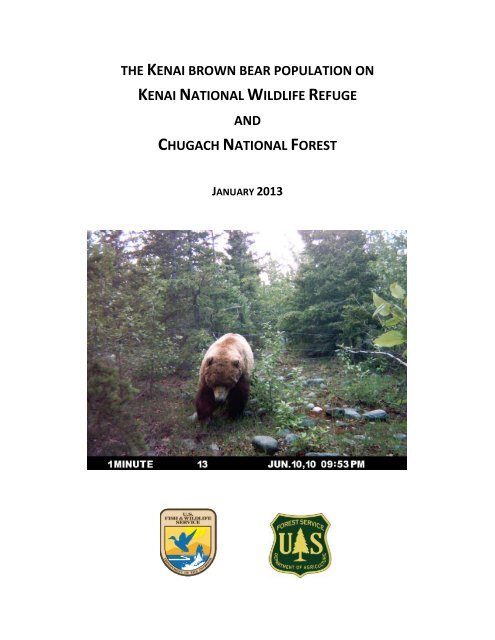

THE KENAI BROWN BEAR POPULATION ON<br />

KENAI NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE<br />

AND<br />

CHUGACH NATIONAL FOREST<br />

JANUARY 2013

THE KENAI BROWN BEAR POPULATION ON<br />

KENAI NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE AND CHUGACH NATIONAL FOREST<br />

January 2013<br />

John M. Mort<strong>on</strong>, Ph.D.<br />

Kenai Nati<strong>on</strong>al <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

U.S. <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Service</strong><br />

P.O. Box 2139<br />

Soldotna, AK 99669<br />

907.260.2815, john_m_mort<strong>on</strong>@fws.gov<br />

Martin Bray<br />

Siuslaw Nati<strong>on</strong>al Forest<br />

U.S. Forest <strong>Service</strong><br />

1130 Forestry Lane<br />

Waldport, OR 97394<br />

541.563.8452, martinbray@fs.fed.us<br />

Gregory D. Hayward, Ph.D.<br />

Alaska Regi<strong>on</strong>, U.S. Forest <strong>Service</strong><br />

161 East 1 st Avenue<br />

Anchorage, AK 99501<br />

907.743.9537, ghayward01@fs.fed.us<br />

Gary C. White, Ph.D. (C<strong>on</strong>sultant)<br />

Department of <strong>Fish</strong>, <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>and</strong> C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> Biology<br />

Colorado State University<br />

Fort Collins, CO 80523<br />

970.491.6678, gary.white@colostate.edu<br />

David Paetkau, Ph.D. (C<strong>on</strong>sultant)<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> Genetics Internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

P.O. Box 274<br />

Nels<strong>on</strong>, BC V1L5P9 Canada<br />

250.352.3563, dpaetkau@wildlifegenetics.ca<br />

2 | P age

ABSTRACT<br />

Field work for a DNA-based, mark-recapture estimate of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai<br />

Nati<strong>on</strong>al <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge <strong>and</strong> Chugach Nati<strong>on</strong>al Forest was c<strong>on</strong>ducted during 1 June–1 July 2010. Bears<br />

were attracted to barbed wire stati<strong>on</strong>s deployed in 145 9km x 9km cells systematically distributed across<br />

11,500 km 2 . Using two Bell 206B helicopters <strong>and</strong> four 2-pers<strong>on</strong> field crews, we deployed <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> stati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

during a 6-day period <strong>and</strong> subsequently revisited <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se stati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> 5 c<strong>on</strong>secutive 5-day trap sessi<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

We collected 11,175 hair samples during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sessi<strong>on</strong>s from both black <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, <strong>and</strong> ano<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r 91<br />

hair samples were collected from o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r sources. Extracted DNA was used to identify individual <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> develop capture histories as input to mark-recapture models. Combined with data from ADFGcollared<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, at least 211 <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s were known to be alive <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Peninsula in 2010. AIC<br />

selecti<strong>on</strong> of DNA-based mark-recapture models, based <strong>on</strong> 99 females <strong>and</strong> 104 males, resulted in an<br />

estimate of 428 (95% lognormal CI = 353–539) <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (including all age classes) <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area.<br />

Extrapolating <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> density estimate of 45.1 <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s per 1,000 km 2 of available habitat <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area to<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Peninsula suggests a peninsula-wide <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> of 624 <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (95% lognormal CI = 504–<br />

772).<br />

Key words: Alaska, <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>, Chugach Nati<strong>on</strong>al Forest, genetics, hair DNA, Kenai Nati<strong>on</strong>al <strong>Wildlife</strong><br />

Refuge, mark-recapture, Pradel model, <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>, Program Mark, Ursus arctos<br />

3 | P age

INTRODUCTION<br />

The grizzly or <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Ursus arctos) <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Peninsula in south-central Alaska is a<br />

keyst<strong>on</strong>e species (IBBST2001). Kenai <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s influence plant distributi<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> abundance through<br />

seed dispersal in feces, transport marine-derived nutrients into terrestrial ecosystems through salm<strong>on</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong> (Hilderbr<strong>and</strong> et al. 2005), <strong>and</strong> possibly regulate ungulate <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s through ne<strong>on</strong>atal<br />

predati<strong>on</strong> under certain c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s (Zager <strong>and</strong> Beecham 2006). Kenai <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s are recognized as a<br />

source of enjoyment by residents <strong>and</strong> visitors, as a source of revenue for commercial wildlife viewing<br />

<strong>and</strong> hunting charters, <strong>and</strong> as a wilderness ic<strong>on</strong> (ADFG 2000).<br />

The 16-km wide isthmus that separates <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 24,300 km 2 Kenai Peninsula from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> adjacent mainl<strong>and</strong><br />

presumably restricts <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> emigrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> immigrati<strong>on</strong>. Talbot et al. (2009) verified that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Kenai <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> is indeed insular, significantly differentiated from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> nearby Anchorage<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong> showing less genetic diversity than mainl<strong>and</strong> Alaskan <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s, based <strong>on</strong> both microsatellite loci <strong>and</strong> mitoch<strong>on</strong>drial DNA c<strong>on</strong>trol regi<strong>on</strong> data.<br />

The Kenai Peninsula is also <strong>on</strong>e of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fastest urbanizing areas in Alaska, with ~10,000 new residents<br />

added every decade since 1960 (U.S. Census Bureau). Over this same 50-year period, Kenai <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

killed in defense of life or property (DLP) have increased from

<strong>and</strong> Chugach Nati<strong>on</strong>al Forest. Sec<strong>on</strong>dary objectives included determining <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sex ratio <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

minimum <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> occurring within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se two Federal c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> units. We c<strong>on</strong>ducted<br />

our study in June, shortly after <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s have left mostly high-elevati<strong>on</strong> dens (Goldstein et al. 2010)<br />

but before most salm<strong>on</strong> have returned to streams <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Peninsula (Jacobs 1989). C<strong>on</strong>sequently,<br />

we included covariates to test our apriori hypo<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ses that capture rates increased with elevati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

were unaffected by proximity to anadromous fish streams at this time of year. We tested for geographic<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> closure by modeling capture rate as functi<strong>on</strong>s of distance to edge of sample frame <strong>and</strong><br />

distance to apparent open edge (Boulanger <strong>and</strong> McLellan 2001). We applied <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pradel model (1996) to<br />

fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r test assumpti<strong>on</strong>s of both geographic <strong>and</strong> demographic closure (i.e., negligible change in birth<br />

<strong>and</strong> death rates) during our study.<br />

METHODS<br />

Study area<br />

The Kenai Peninsula juts into <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Gulf of Alaska, embraced <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> west by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Cook Inlet <strong>and</strong> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> east<br />

by Prince William Sound (Figure 1). Elevati<strong>on</strong>s range from sea level to 2,015 m in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Mountains.<br />

Biodiversity is unusually high for this latitude because of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> juxtapositi<strong>on</strong> of two biomes <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

peninsula: <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn fringe of Sitka spruce-dominated (Picea sitchensis) coastal rainforest <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

eastern flank of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Mountains, <strong>and</strong> transiti<strong>on</strong>al boreal forest to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> west. The latter forest types<br />

include white (P. glauca), black (P. mariana), <strong>and</strong> Lutz (P. X Lutzii) spruces with an admixture of aspen<br />

(Populus tremuloides) <strong>and</strong> birch (Betula neoalaskana)(Table 1). Extensive Sphagnum peatl<strong>and</strong>s are<br />

interspersed am<strong>on</strong>g spruce in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Lowl<strong>and</strong>s. Lichen-dominated tundra replaces mountain<br />

hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana) <strong>and</strong> sub-alpine shrub above treeline.<br />

The study area includes 11,700 km 2 of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> peninsula <strong>on</strong> l<strong>and</strong>s administered by Kenai Nati<strong>on</strong>al <strong>Wildlife</strong><br />

Refuge <strong>and</strong> Chugach Nati<strong>on</strong>al Forest (Figs. 1,2). The area is bounded in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> north <strong>and</strong> northwest by<br />

Cook Inlet <strong>and</strong> Turnagain Arm, in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> east by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Sargent Icefield, in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> south by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Harding Icefield<br />

<strong>and</strong> Wosnesenski-Grewingk Glacier complex, <strong>and</strong> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> west by Refuge boundaries. The study area<br />

includes 127 (1,390 km) of 250 named streams identified <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Peninsula in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Catalog of<br />

Waters Important for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Spawning, Rearing or Migrati<strong>on</strong> of Anadromous <strong>Fish</strong>es<br />

(http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/sf/SARR/AWC/).<br />

With <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> excepti<strong>on</strong> of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> southwest corner of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> peninsula (i.e., south of Caribou Hills), <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area<br />

effectively includes all known <strong>and</strong> modeled areas of <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> habitati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> peninsula (IBBST<br />

2001). On average, 87% (SE = 0.03) of 144,024 telemetry locati<strong>on</strong>s from 125 <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> adult <strong>and</strong><br />

subadult females radio-collared by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> IBBST during 1987-2005 were <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area (Fig. 3).<br />

Excluding all telemetry locati<strong>on</strong>s collected after 1 July reduces <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> data set to 7,413 locati<strong>on</strong>s from 114<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> females; 11 females (9%) were never <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sample frame during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> period when this<br />

study was c<strong>on</strong>ducted. The proporti<strong>on</strong> of telemetry points <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sample frame, averaged for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 114<br />

females, was 84% (SE = 0.03); 75 of 114 females were <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sample frame during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> entire sampling<br />

5 | P age

window. Similarly, of 74 <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> females for which den sites are known from 1996-2003, 84%<br />

denned at least <strong>on</strong>ce <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area (Figure 2).<br />

Study design<br />

We n<strong>on</strong>invasively collected <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> (<strong>and</strong> black; Ursus americanus) <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> hairs at barbed-wire stati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

subjectively placed within 145 9km x 9km cells systematically arrayed across <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area (Figure 4).<br />

After an initial 6-day deployment period, we employed a rotating panel design in which five panels of 29<br />

cells each were revisited <strong>on</strong> five c<strong>on</strong>secutive 5-day trap sessi<strong>on</strong>s. All cells were visited by two-pers<strong>on</strong><br />

field crews transported by Bell 206-B Jet Ranger helicopters over 31 c<strong>on</strong>secutive days from 1 June–1 July<br />

2010. Field crews <strong>and</strong> helicopters were stati<strong>on</strong>ed in Soldotna <strong>and</strong> Moose Pass (Figure 1).<br />

Using expert judgment (see criteria below), we a priori selected primary <strong>and</strong> sec<strong>on</strong>dary sites within each<br />

cell <strong>on</strong> which to place hair stati<strong>on</strong>s; <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> final coordinates were frequently adjusted in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> field to better<br />

reflect in situ c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s. If hair samples were not obtained by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> end of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> third trap sessi<strong>on</strong>, we<br />

ei<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r moved <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> trap to ano<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r site within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cell or added a sec<strong>on</strong>d trap to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cell. In additi<strong>on</strong> to<br />

hair samples collected at stati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> grid, we supplemented sampling with hair collected at a<br />

permitted black <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> baiting stati<strong>on</strong> (for hunting), <strong>on</strong> rub trees, <strong>and</strong> from live <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s h<strong>and</strong>led during<br />

collaring operati<strong>on</strong>s incidental to this study.<br />

Site selecti<strong>on</strong> for hair sampling stati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Using GIS, we eliminated all l<strong>and</strong>s from sampling that are restricted by ADFG for black <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> baiting: no<br />

baiting within 1 mile of any residence, including seas<strong>on</strong>ally occupied dwellings, developed recreati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

facilities or campgrounds; no baiting within 1/4 mile of any publicly-maintained road, trail, or <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Alaska<br />

Railroad; <strong>and</strong> no baiting within 1/4 mile from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> shoreline of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai, Kasilof <strong>and</strong> Swans<strong>on</strong> Rivers<br />

(including Kenai <strong>and</strong> Skilak Lakes). In total, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se buffered (mostly linear) areas c<strong>on</strong>stituted 16% of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

study area, mostly in relatively high human use areas.<br />

We used <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> following ranked criteria to a priori select two locati<strong>on</strong>s for hair sampling stati<strong>on</strong>s within<br />

each cell from digital ortho quads (DOQs):<br />

1) adequate space for helicopter access;<br />

2) ≥200 m from anthropogenic features (trails, cabins, roads);<br />

3) riparian/wetl<strong>and</strong> corridors associated with stream morphology were given first priority;<br />

4) o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r travel corridors c<strong>on</strong>sidered were associated with disc<strong>on</strong>tinuity between vegetati<strong>on</strong><br />

types, avalanche chutes, shoulders between peaks, <strong>and</strong> ridges; <strong>and</strong><br />

5) o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r things being equal, trying to ensure spatial separati<strong>on</strong> am<strong>on</strong>g sites within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cell.<br />

Hair stati<strong>on</strong>s, sampling <strong>and</strong> processing<br />

Hair was sampled from <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s that stepped over or crawled under barbed wire to investigate a simulated<br />

cache laced with lure (Mowat <strong>and</strong> Strobeck 2000). At each stati<strong>on</strong>, we strung two 30-m l<strong>on</strong>g doublestr<strong>and</strong>ed<br />

barbed wires around ≥ 3 trees or rebar stakes to approximate an equilateral triangle at two<br />

6 | P age

heights (20–30 <strong>and</strong> 60–70 cm above ground) to increase <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> likelihood of sampling both adult <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>and</strong><br />

cubs. Logs, rocks, litter, <strong>and</strong> o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r debris were piled in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> center of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se hair stati<strong>on</strong>s to simulate a<br />

cache. We used ≥ 3 liters of fermented 3:1 cow blood (The Beef Shop, Centralia, WA) <strong>and</strong> pure,<br />

unprocessed fish oil (Kodiak <strong>Fish</strong> Meal Company), respectively, as lure per stati<strong>on</strong> per visit. O<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r<br />

substances (e.g., fruit extract, spice oils, anise) were used to augment lures. Signs were posted to both<br />

warn <strong>and</strong> inform public who may have accidentally encountered <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se sites.<br />

All hair was collected with forceps <strong>and</strong>/or gloves, <strong>and</strong> placed in coin envelopes; <strong>on</strong>e envelope for each<br />

barb cluster. Each coin envelope was bar-coded (Lint<strong>on</strong> Co.) <strong>and</strong> labeled with stati<strong>on</strong> ID, date, barb<br />

number, <strong>and</strong> locati<strong>on</strong> (upper str<strong>and</strong>, lower str<strong>and</strong>). Barbs were burned with a propane torch to remove<br />

any remaining hair after collecti<strong>on</strong>. Any hair <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> ground below barbed wire str<strong>and</strong>s were collected<br />

but not used in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> analysis. Immediately before leaving, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> simulated cache was freshened with more<br />

lure.<br />

Hair was dried overnight in opened envelopes if <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> samples were wet at time of collecti<strong>on</strong>. Hair was<br />

stored at room temperature with desiccant. To minimize DNA degradati<strong>on</strong>, hair samples were sent to<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> lab as so<strong>on</strong> as possible after field work was completed. All unused hair samples (from both <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<strong>and</strong> black <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s) were archived.<br />

Genetic analysis<br />

Bear species identificati<strong>on</strong>, individual genotyping, <strong>and</strong> sex determinati<strong>on</strong> from DNA in hairs were<br />

c<strong>on</strong>ducted by <strong>Wildlife</strong> Genetics Internati<strong>on</strong>al Inc. (Nels<strong>on</strong>, BC) following quality c<strong>on</strong>trol methods<br />

specified in Paetkau (2003) <strong>and</strong> validated through blind testing by Kendall et al. (2009). To reduce costs,<br />

samples were excluded from genetic analysis if <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y c<strong>on</strong>tained no guard hairs with roots, <strong>and</strong> < 5<br />

underfur, or if <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y were clearly from ungulates based <strong>on</strong> appearance. We also excluded over 5,000<br />

guard hair samples that were jet black al<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir entire length, which we felt could be reliably<br />

identified as black <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> hair in this study area. DNA was extracted from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> remaining samples using<br />

QIAGEN DNeasy tissue kits, with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> target of using 10 guard hair roots if available. For guard hairs, we<br />

identified root bulbs under a microscope <strong>and</strong> used <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> bottom 5–10 mm of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> hair for extracti<strong>on</strong>. For<br />

underfur, where d<strong>and</strong>er caught up in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> hair can be a significant source of DNA, clumps of hair were<br />

wound toge<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r <strong>and</strong> placed into <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> first extracti<strong>on</strong> buffer (buffer ATL). In both cases, a warm water<br />

wash was used to remove dirt from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> hairs before placing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>m in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> extracti<strong>on</strong> buffer.<br />

DNA extracts were prescreened with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> marker G10J, both to weed out weak samples <strong>and</strong> to<br />

separate black <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> samples from <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> samples, based <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> exclusive presence of oddnumbered<br />

allele lengths in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> former species <strong>and</strong> even-numbered alleles in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> latter. To identify<br />

individuals, we used 7 microsatellite markers (G1A, G10H, G10J, G1D, G10B, MU50, MU23) with<br />

average heterozygosity > 0.72 in Kenai <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, as well as an amelogenin sex marker.<br />

The multilocus microsatellite analyses were performed in 3 phases. First, an initial pass was made with all<br />

8 markers, including reanalysis of G10J to c<strong>on</strong>trol for sample h<strong>and</strong>ling errors. Samples that produced solid<br />

7 | P age

data for

streams (DTA). For <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se variables, we averaged over all captures of an individual. We also c<strong>on</strong>sidered<br />

thresholds of 4.5 <strong>and</strong> 9 km for DTE, <strong>and</strong> 4.5, 9, 18 <strong>and</strong> 27 km for DTOpenE; i.e., <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> values were<br />

truncated when <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> true value exceeded <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se values. We modeled trapping effort as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> number of<br />

days of hair trap availability during each of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5 occasi<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

To assess <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> potential for use of Pledger heterogeneity models (Pledger 2005) for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5 trapping<br />

occasi<strong>on</strong>s, a binomial distributi<strong>on</strong> restricted to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> positive integers (zero-truncated) was fitted to<br />

capture frequencies for females <strong>and</strong> males separately. This model tested whe<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> observed<br />

frequencies of female <strong>and</strong> male captures could have come from a zero-truncated binomial distributi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

If so, observed heterogeneity was not str<strong>on</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Pledger models were not deemed necessary. If<br />

frequencies did not follow a zero-truncated binomial, Pledger models were deemed necessary <strong>and</strong> were<br />

included during subsequent modeling. Subsequent modeling of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> combined data set c<strong>on</strong>sidered<br />

detecti<strong>on</strong> probabilities for occasi<strong>on</strong> 0 to be sex-specific, since more females than males carried radio<br />

collars <strong>and</strong> were known to be alive <strong>and</strong> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area. The time-varying models c<strong>on</strong>sidered for<br />

occasi<strong>on</strong>s 1– 5 were c<strong>on</strong>stant capture probabilities across time <strong>and</strong> time-specific capture probabilities.<br />

The basic time-<strong>and</strong>-individual-varying models c<strong>on</strong>sidered for occasi<strong>on</strong>s 1 – 5 were <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> time-varying<br />

models plus a sex effect <strong>and</strong> a sex interacti<strong>on</strong>. In additi<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> covariates DTE, DTOpenE, ELEV <strong>and</strong> DTA<br />

were added to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se models, as well as DTE with thresholds of 4.5 km <strong>and</strong> 9 km <strong>and</strong> DTOpenE with<br />

thresholds of 4.5, 9, 18, <strong>and</strong> 27 km. To evaluate time-specific effects <strong>on</strong> detecti<strong>on</strong> probabilities, a fully<br />

time-specific model with 5 parameters <strong>and</strong> a trapping effort model with 2 parameters were used, with<br />

values of 826, 717, 767, 731, <strong>and</strong> 752 hair-snare days for each of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5 occasi<strong>on</strong>s. The Huggins<br />

c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>al likelihood parameterizati<strong>on</strong> (Huggins 1989, 1991; Alho 1990) was used to estimate<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> size as a derived parameter:<br />

N ˆ<br />

=<br />

M t<br />

+ 1<br />

∑<br />

i=<br />

1<br />

1−<br />

6<br />

∏<br />

j=<br />

1<br />

1<br />

(1 −<br />

ˆ<br />

p ij<br />

)<br />

All models assume no behavioral effect of capture; i.e., <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> capture probability of <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s that have been<br />

detected <strong>on</strong>ce does not change for additi<strong>on</strong>al detecti<strong>on</strong>s. Analyses were c<strong>on</strong>ducted with Program MARK<br />

(White <strong>and</strong> Burnham 1999) using informati<strong>on</strong>-<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>oretic model selecti<strong>on</strong> criteria (AIC c ) <strong>and</strong> model<br />

averaging of <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> estimates (Burnham <strong>and</strong> Anders<strong>on</strong> 2002). AICc weights for Pledger models<br />

were computed for just <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> grid-based hair data to fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r assess <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> need for this mixture model<br />

relative to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> suite of models c<strong>on</strong>sidered.<br />

To fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r assess <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> assumpti<strong>on</strong>s of both demographic <strong>and</strong> geographic closure, we c<strong>on</strong>structed 4<br />

models with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pradel data type (Pradel 1996) in Program MARK using just <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5 hair snare sampling<br />

occasi<strong>on</strong>s. Models c<strong>on</strong>sidered were both apparent survival (φ) <strong>and</strong> fecundity (f) estimated, φ fixed to 1<br />

with f estimated, f fixed to 0 with φ estimated, <strong>and</strong> both φ fixed to 1 <strong>and</strong> f fixed to 0.<br />

9 | P age

RESULTS<br />

Field implementati<strong>on</strong><br />

We originally proposed to sample 190 hair stati<strong>on</strong>s deployed in a systematic grid of 8km x 8km cells.<br />

However, it became very apparent <strong>on</strong> Day 1 (1 June) that we would have trouble completing this sample<br />

design. Although we were deploying stati<strong>on</strong>s in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> panel closest to fuel depots, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Moose Pass <strong>and</strong><br />

Soldotna helicopters logged 6.9 <strong>and</strong> 7.5 hours in flight time, respectively. On Day 2 (2 June), we<br />

decreased <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> number of hair stati<strong>on</strong>s from 190 to 145 by increasing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cell size to 9km x 9km.<br />

However, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> overall spatial footprint of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> panels was not decreased, <strong>and</strong> it was reflected in flight<br />

times of 7.2 <strong>and</strong> 7.3 hours for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Moose Pass <strong>and</strong> Soldotna helicopters, respectively. C<strong>on</strong>sequently, <strong>on</strong><br />

Day 3 (3 June), we completely reshuffled <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> panels, clustering cells around fixed <strong>and</strong> mobile fuel depots<br />

to reduce daily flight time (Figure 4). We had lost irretrievable time by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n, so <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> initial deployment of<br />

stati<strong>on</strong>s required 6 (ra<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r than 5) days, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>reby extending <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sampling period through 1 July.<br />

Despite an unusually rainy <strong>and</strong> cold June in 2010, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sampling schedule for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> panels was sustainable<br />

after we established <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 9 km x 9 km grid array (Figure 4). A stati<strong>on</strong> was never deployed in cell 141<br />

because of persistent snow cover early, <strong>and</strong> poor wea<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r later in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study. Due to a prol<strong>on</strong>ged period<br />

of inclement wea<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r in Prince William Sound, we were unable to sample 6 cells<br />

(116,135,136,137,145,146) in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> same panel (Figure 4, panel E) during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2 nd revisit; cell 135 was also<br />

not sampled during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 4 th revisit for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> same reas<strong>on</strong>. Visits to a cell were occasi<strong>on</strong>ally delayed due to<br />

poor wea<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r or an unusually persistent <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> but, with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> excepti<strong>on</strong> of above 6 cells, all cells were<br />

sampled before <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> next scheduled visit.<br />

Hair samples<br />

We collected 11,175 samples of <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong> black <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> hair from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 144 primary stati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> 7<br />

sec<strong>on</strong>dary stati<strong>on</strong>s. The 1 st revisit had <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> lowest return (1,550 samples) presumably because trap<br />

sessi<strong>on</strong> length varied from 1–9 days due to modificati<strong>on</strong>s to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> grid design during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> first 3 days of<br />

deployment. However, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> number of samples collected exceeded 2,100 for each of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r 4 revisit<br />

sessi<strong>on</strong>s, each averaging 5 days.<br />

In additi<strong>on</strong> to hair samples collected at hair stati<strong>on</strong>s with lures, 91 samples were collected from rub<br />

trees by USFS staff at Quartz Creek <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>fluence of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai <strong>and</strong> Russian Rivers, <strong>and</strong> by a USFWS<br />

technician who collected samples from his permitted black <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> baiting stati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Lowl<strong>and</strong>s.<br />

In total, 11,266 hair samples were c<strong>on</strong>sidered in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se analyses.<br />

Genotypes<br />

DNA was extracted from 2,671 of 11,266 samples. This subset included 224 extracti<strong>on</strong>s of samples that<br />

were visually classified as black <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> samples, starting with 50 samples that were extracted specifically<br />

to test <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> visual species identificati<strong>on</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n adding 174 samples that were extracted at a later<br />

date for an occupancy analysis that will be <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> subject of a future report. Some of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se 224 samples<br />

failed during genetic analysis, but <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> successful samples all had odd numbered alleles at G10J,<br />

10 | P age

c<strong>on</strong>firming <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> accuracy of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> visual species identificati<strong>on</strong>s as black <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s. The prescreen process with<br />

marker G10J produced high c<strong>on</strong>fidence, even-numbered scores indicating <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s for 1,226 of<br />

2,671 samples, which went <strong>on</strong> to genotyping with 8 markers. During multilocus genotyping, 1,034<br />

samples produced high-c<strong>on</strong>fidence scores for all 8 markers, <strong>and</strong> were <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>refore used for individual<br />

identificati<strong>on</strong>. There were 211 unique multilocus genotypes represented by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1,034 successful <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> samples, of which 166 were identified from hair collected <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sample frame. Of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 211 unique<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (i.e., excluding ADFG <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s), 47 were detected in ≥ 2 sessi<strong>on</strong>s, 5 were detected in 1 sessi<strong>on</strong><br />

but also identified in o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r studies or n<strong>on</strong>study samples, 114 were captured <strong>on</strong>ce, 11 were captured<br />

<strong>on</strong>ly in n<strong>on</strong>study samples, <strong>and</strong> 34 were not captured but previously identified in o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r studies or<br />

n<strong>on</strong>study samples.<br />

Based <strong>on</strong> sex <strong>and</strong> perfect matches at 6–9 loci, 32 of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s were identified as previously h<strong>and</strong>led<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s by ADFG or <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> IBBST. Six of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> previously h<strong>and</strong>led individuals were males, captured by ADFG or<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> IBBST during radio-collaring operati<strong>on</strong>s that targeted females. Five of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 34 radio-collared <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> females (15%) known to be <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sample frame immediately before or during June 2010 were<br />

matched with genotypes identified by hair sampling.<br />

Species identity was c<strong>on</strong>firmed through a clustering analysis based <strong>on</strong> 6 microsatellite markers,<br />

excluding G10J to ensure independence of tests. Bears with even- <strong>and</strong> odd-numbered G10J alleles<br />

formed 2 discrete clusters, c<strong>on</strong>firming that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> G10J data had accurately separated species.<br />

Genotyping errors normally create pairs of genotype from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> same individual that mismatch at 1<br />

marker (Paetkau 2003). Following error-checking <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re was <strong>on</strong>ly 1 such pair am<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 211 <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

genotypes that we recognized, <strong>and</strong> this pair was solidly c<strong>on</strong>firmed, first through reanalysis of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

mismatching marker, <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>n through analysis of 16 additi<strong>on</strong>al markers, several of which mismatched.<br />

There were also 8 pairs of multilocus <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> genotypes that matched at 6 of 8 markers, each of<br />

which was c<strong>on</strong>firmed through reanalysis of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> mismatching markers. Extensive blind testing has shown<br />

that this protocol effectively prevents <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> recogniti<strong>on</strong> of false individuals through genotyping error<br />

(Kendall et al. 2009).<br />

In additi<strong>on</strong> to providing reassurances about genotyping errors, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> observati<strong>on</strong> of just 1 pair of <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s whose genotypes matched at 7 of 8 markers indicates a low probability that we sampled any pair<br />

of <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s with identical 8-locus genotypes. This is because matches at all 8 markers are roughly 10 times<br />

less likely than matches at 7 of 8 markers, just as matches at 6 of 8 markers are more comm<strong>on</strong> than<br />

matches at 7 markers (Paetkau 2003).<br />

Radio-collared female <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

We located 30 radio-collared female <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s during 5 days of aerial tracking from 26 June–4 July<br />

2010. We combined <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se locati<strong>on</strong>s with telemetry data received from ADFG in March 2012 which<br />

represented data collected during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study but previously unavailable. Toge<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> samples of radio-<br />

11 | P age

collared female <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s provided geographic locati<strong>on</strong>s of 39 females known to be alive in June<br />

2010 <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Peninsula; 5 were not <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sample frame (Figure 6).<br />

Populati<strong>on</strong> estimati<strong>on</strong><br />

All sources of informati<strong>on</strong> for <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Peninsula in June 2010 identified 243 <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, of which 211 were identified genetically <strong>and</strong> 32 had been h<strong>and</strong>led by ADFG but were not<br />

detected during n<strong>on</strong>-invasive hair sampling. After eliminating <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (n = 40) for which <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re were no<br />

geographic coordinates, ei<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r because <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y were not located (if collared) or were sampled outside <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

study area, we c<strong>on</strong>sidered 203 <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (99 females, 104 males) for analysis. Of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se 203 individuals, 65<br />

females <strong>and</strong> 101 males were detected at hair stati<strong>on</strong>s, 5 females <strong>and</strong> 3 males were detected at rub<br />

trees, <strong>and</strong> 29 females were known to be alive <strong>and</strong> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sample frame during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study period.<br />

Occasi<strong>on</strong> 0 was composed of 41 <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s known to be alive <strong>and</strong> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sample frame during <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

study, including 34 collared females <strong>and</strong> 7 <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s captured <strong>on</strong> rub trees [note: 1 sow was both collared<br />

<strong>and</strong> detected <strong>on</strong> a rub tree].<br />

Capture frequencies of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s detected <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> sample frame (n = 166) were 3 detecti<strong>on</strong>s (3 females,<br />

5 males), 2 detecti<strong>on</strong>s (17 females, 21 males), <strong>and</strong> 1 detecti<strong>on</strong> (45 females, 75 males). The zerotruncated<br />

binomial fit to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se frequencies suggested no lack of fit (P = 0.959 females, P = 0.791 for<br />

males). Fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> AICc weight for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> time-specific Pledger model for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> grid-based hair data was<br />

<strong>on</strong>ly 0.0054, <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 3-parameter Pledger mixture model (no time variati<strong>on</strong>) received no weight, so<br />

Pledger models were not c<strong>on</strong>sidered in subsequent analyses. With <strong>on</strong>ly 5 occasi<strong>on</strong>s, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> level of<br />

individual heterogeneity has to be relatively high (i.e., at least a few animals captured <strong>on</strong> all 5 occasi<strong>on</strong>s)<br />

before <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pledger mixture models perform reas<strong>on</strong>ably.<br />

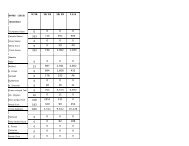

Estimates of capture probabilities tended to increase with each successive trap sessi<strong>on</strong> (Table 4) despite<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> fact that <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s were exposed to traps for approximately <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> same time period (~ 5 days) during each<br />

of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5 occasi<strong>on</strong>s. C<strong>on</strong>sequently, model selecti<strong>on</strong> results (Table 2) suggested that a time-specific model<br />

was necessary to explain <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> variati<strong>on</strong> in detecti<strong>on</strong> probabilities for occasi<strong>on</strong>s 1–5, <strong>and</strong> that an additive<br />

sex effect was needed to explain differences between sexes. These effects resulted in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> base model of<br />

{sex*p(0), sex+p(t)}. ELEV <strong>and</strong> DTE covariates were useful predictors of detecti<strong>on</strong> probabilities when<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se covariates were added to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> base model {sex*p(0), sex+p(t)}, although DTE did not improve up<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> base model. Detecti<strong>on</strong> probabilities declined with ELEV (Figure 7) <strong>and</strong> increased with smaller DTE<br />

values (Figure 8); i.e., <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s closer to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> edge had higher detecti<strong>on</strong> probabilities. When DTA <strong>and</strong><br />

DTOpenE were added to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> base model {sex*p(0), sex+p(t)}, as well as truncated values of DTE <strong>and</strong><br />

DTOpenE, n<strong>on</strong>e of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> models produced smaller AIC c values than <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> base model. Model averaging of<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> estimates (Table 3) suggests that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re were 428 (95% lognormal CI = 353–539) <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s of all ages <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area in June 2010, of which 215 were females <strong>and</strong> 213 were males.<br />

The model weights for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 4 Pradel models c<strong>on</strong>sidered (Table 5) show that 98% of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> AICc weight is <strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> model with φ fixed to 1 <strong>and</strong> f fixed to 0. That is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> model best supported assumes no emigrati<strong>on</strong> or<br />

12 | P age

immigrati<strong>on</strong>, <strong>and</strong> thus provides fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r evidence that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> hair snare sampling grid can be assumed<br />

geographically <strong>and</strong> demographically closed.<br />

DISCUSSION<br />

This study produced <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> first empirically-based estimate of <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> abundance <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai<br />

Peninsula, Alaska. As with all <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> estimates of vertebrates in remote locati<strong>on</strong>s, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study design<br />

was a compromise am<strong>on</strong>g fiscal c<strong>on</strong>straints, logistics, <strong>and</strong> statistical rigor. The resulting estimate<br />

provides a sound foundati<strong>on</strong> for management agencies <strong>and</strong> o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rs to c<strong>on</strong>sider l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> resource<br />

decisi<strong>on</strong>s. Favorable characteristics of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area combined with a robust survey sample design<br />

al<strong>on</strong>g with careful analysis resulted in an estimate that fit <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> assumpti<strong>on</strong>s for mark-recapture<br />

remarkably well. Despite <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se strengths, applicati<strong>on</strong> of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> results will be most effective if certain<br />

characteristics of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> investigati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> modeling process are understood. Below we examine <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

characteristics of our estimate to clarify interpretati<strong>on</strong> of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> results.<br />

Study design <strong>and</strong> modeling c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Our study design was similar to that used by Poole et al. (2001) to estimate <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> grizzly <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Prophet River in British Columbia. They used a sample frame of 103 9 x 9 km cells <strong>on</strong> an area<br />

slightly smaller than our study area. They used 1 stati<strong>on</strong> within each cell with a single barbed-wire<br />

enclosure, but increased capture rates by moving stati<strong>on</strong>s between each of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5 trap occasi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> by<br />

adding new lures. We chose to increase our capture rates by using 2 barbed-wire str<strong>and</strong>s, using<br />

commercial lures in additi<strong>on</strong> to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cow blood <strong>and</strong> fish oil lure, <strong>and</strong> adding sec<strong>on</strong>dary stati<strong>on</strong>s or moving<br />

stati<strong>on</strong>s within cells but <strong>on</strong>ly when <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> primary site performed poorly. We also improved our <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

estimate by using supplemental DNA sources: ad hoc sampling of rub trees (Boulanger et al. 2008) <strong>and</strong><br />

telemetry data (Boulanger et al. 2002). We chose to tradeoff intensive sampling with smaller cells<br />

(which may have allowed for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> detecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> modeling of individual heterogeneity; Boulanger et al.<br />

2002) for a more extensive sample frame that encompassed virtually all of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> known <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

habitat <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Nati<strong>on</strong>al <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge <strong>and</strong> Chugach Nati<strong>on</strong>al Forest, an area that approximates<br />

70% of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> known <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> habitat <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Peninsula.<br />

The short trap sessi<strong>on</strong> (5 days), <strong>and</strong> c<strong>on</strong>sequently <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>strained sampling window (June), makes our<br />

study unique in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> published literature. Poole et al. (2001) <strong>and</strong> Kendall et al. (2009), for example, used<br />

trap sessi<strong>on</strong>s of 12–14 days. However, both of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>s were inl<strong>and</strong> grizzlies, not salm<strong>on</strong>dependent<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (Hilderbr<strong>and</strong> et al. 1999). C<strong>on</strong>sequently, although we recognized that shorter<br />

trap sessi<strong>on</strong>s might reduce capture rates, we were c<strong>on</strong>cerned that extending <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study into July when<br />

most salm<strong>on</strong> return to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Peninsula would reduce both <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> effectiveness of our lures <strong>and</strong> our<br />

study design (because <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s begin c<strong>on</strong>gregating al<strong>on</strong>g streams; Figure 8b). To test for this characteristic<br />

of our design, we examined capture rates in relati<strong>on</strong> to salm<strong>on</strong> streams -- as expected (given our spring<br />

trapping), distance to anadromous streams did not significantly improve <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> model (Table 2).<br />

13 | P age

The shorter trap sessi<strong>on</strong>s also limited exposure of samples to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> elements which can degrade DNA<br />

samples. Our genotyping success was comparatively high (D. Paetkau, pers. comm.). The short trapping<br />

sessi<strong>on</strong> can be particularly important in DNA-sample quality if <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re is a bias towards samples being<br />

collected shortly after deployment when <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> lure is freshest. Fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rmore, keeping <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> trap sessi<strong>on</strong><br />

short significantly reduced <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cost of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> two helicopters <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir fuel were <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> single<br />

biggest expense. Finally, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> short sampling window provides reas<strong>on</strong>able assurance of demographic<br />

closure (see below).<br />

Per-occasi<strong>on</strong> capture probabilities in our study did not exceed 0.17 for males <strong>and</strong> 0.11 for females (Table<br />

4). These values were slightly lower than <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> mean capture probability of 0.19 per sessi<strong>on</strong> reported by<br />

Poole et al. (2001) <strong>and</strong> generally lower than <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> observed capture probabilities of 0.1–0.25 reported by<br />

Kendall et al. (2009). The low number of trap occasi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> low detecti<strong>on</strong> probabilities have two<br />

negative c<strong>on</strong>sequences. First, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se features result in less precise estimates of abundance. Sec<strong>on</strong>d,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se characteristics make it difficult to apply recently-developed Pledger models. We expect individual<br />

heterogeneity of capture probabilities to exist in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> (i.e., that each animal has its own innate<br />

detecti<strong>on</strong> probability), <strong>and</strong> Pledger models have been dem<strong>on</strong>strated as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> superior choice for<br />

estimating abundance when capture probabilities are heterogeneous. Unfortunately, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pledger<br />

model, as well as all models that include a comp<strong>on</strong>ent to model individual heterogeneity, performs<br />

poorly when <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> data display little individual heterogeneity <strong>and</strong>/or capture probabilities are low.<br />

Therefore, applicati<strong>on</strong> of Pledger models was not appropriate for our data even though we suspect <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

models fit <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> underlying capture process.<br />

Model selecti<strong>on</strong> with AIC is used in our analyses because of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> need to recognize uncertainty in which<br />

models should be used to make inference about <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> size (Burnham <strong>and</strong> Anders<strong>on</strong> 2002). A<br />

wide range of models is presented in Table 2. The “best” model is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> model with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> smallest, or<br />

minimum, AIC value. However, o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r models in Table 2 are “close” to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> minimum model shown at <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

top of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> list. To account for uncertainty am<strong>on</strong>g models, we use model averaging, based <strong>on</strong> model AIC<br />

weights shown in Table 2, to obtain an estimate of <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> size. If we chose to <strong>on</strong>ly present <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

estimates from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> minimum AIC model, we know from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ory <strong>and</strong> simulati<strong>on</strong> that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>fidence<br />

intervals from this model would be unrealistically narrow because a single model cannot account for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

model selecti<strong>on</strong> uncertainty. By taking a weighted average of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> estimates, we have<br />

accounted for model selecti<strong>on</strong> uncertainty in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> results presented in Table 3.<br />

Lognormal c<strong>on</strong>fidence intervals are presented in Table 3 because of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> skewness of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> distributi<strong>on</strong> of<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> estimates. This is a well established approach that accounts for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> firm lower bound <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

number of animals in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> provided by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> number of individuals known to be alive in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. In c<strong>on</strong>trast, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> upper bound is not c<strong>on</strong>strained <strong>and</strong> results in a l<strong>on</strong>g upper tail <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

sampling distributi<strong>on</strong> of <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> estimates.<br />

14 | P age

Populati<strong>on</strong> estimate <strong>and</strong> model assumpti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Based <strong>on</strong> 203 individual genotypes, we estimated that 428 <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s were <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Nati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

<strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge <strong>and</strong> Chugach Nati<strong>on</strong>al Forest in June 2010. Although we detected 41% fewer females<br />

than males, model-averaged <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> estimates show essentially <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> same number by sex (Table 3).<br />

The estimate of females is increased c<strong>on</strong>siderably by accounting for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> females known to be <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

study area but never detected at hair stati<strong>on</strong>s (34 females <strong>and</strong> 3 males were known to be alive <strong>and</strong> <strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area, but never detected at hair stati<strong>on</strong>s). Model-averaged <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> estimates for females<br />

<strong>and</strong> males from just hair stati<strong>on</strong>s were 114 <strong>and</strong> 194, respectively (Table 3). The difference in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

estimates from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> full analysis that included <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s known to be <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area but never<br />

detected at hair stati<strong>on</strong>s, versus <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> analysis of <strong>on</strong>ly hair-snare detecti<strong>on</strong>s, provides some idea of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

bias of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> hair-stati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly data; i.e., not all <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s were sampled by hair stati<strong>on</strong>s with equal probability.<br />

For example, Kendall et al. (2009) found that <strong>on</strong>ly 61% of females <strong>and</strong> 35% of males known to be <strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir study area in nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn M<strong>on</strong>tana were detected by hair traps. However, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> inclusi<strong>on</strong> of data from<br />

previously-h<strong>and</strong>led <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (e.g., radio-collared) <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study area <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s detected by rub trees<br />

decreased <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> bias of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir final estimate, just as <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> inclusi<strong>on</strong> here of <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s known to be <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> study<br />

area has decreased <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> bias of our estimates.<br />

Our evaluati<strong>on</strong> of capture probabilities resulted in a more pr<strong>on</strong>ounced adjustment for females. Females<br />

of all ages had a lower hair stati<strong>on</strong> detecti<strong>on</strong> probability than males, as shown by Figures 7 <strong>and</strong> 8, <strong>and</strong><br />

dem<strong>on</strong>strated by radio-collared subadult <strong>and</strong> adult females known to be in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> but never<br />

detected at hair stati<strong>on</strong>s. The model-averaged estimates for females <strong>and</strong> males from just grid-based<br />

detecti<strong>on</strong>s are 114 <strong>and</strong> 194, respectively; with inclusi<strong>on</strong> of <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s known to be in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

numbers increases to 215 <strong>and</strong> 214. The final estimate for females is almost twice <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estimate from<br />

grid-based data, whereas <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> estimate for males increases <strong>on</strong>ly ~9%. Females were under-represented<br />

in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> grid-based sampling presumably because some cohorts may behave differently (e.g., sows with<br />

cubs of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> year tend to move little during June) <strong>and</strong> because males have almost twice <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> home range<br />

(950 km 2 ) as females (401 km 2 ) <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Peninsula (Jacobs 1989). Fur<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> presence of 34<br />

females in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> analysis that were not detected at hair stati<strong>on</strong>s increases <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> number of females known<br />

to be alive <strong>and</strong>, because <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se 34 <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s were undetected, dem<strong>on</strong>strates <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> lower capture probability<br />

of females. Both of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se effects result in increasing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> estimate.<br />

The estimated 50:50 sex ratio that results from our most robust estimate of abundance is unusual in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> literature. Grizzly <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g> studies elsewhere have generally estimated more adult females<br />

than males, typically 60:40; e.g., Pears<strong>on</strong> (1975), Craighead et al. (1974). One possible interpretati<strong>on</strong> is<br />

that our <str<strong>on</strong>g>populati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> estimate is still biased low for females, even after adjusting <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> modeled estimate<br />

with data from collared <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>and</strong> rub trees. Alternatively, it is also likely that adult female mortality <strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kenai Peninsula may be skewed high. Unpublished ADFG data from 1967-2011 shows that of 122<br />

adult <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g>s killed by humans from sources o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r than hunting (i.e., DLPs, illegal take, road kills,<br />

<strong>and</strong> management kills), 69% were females. Similarly, an analysis of <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> age structure of 256 <str<strong>on</strong>g>brown</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>bear</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

females captured from 1995–1999 suggested that 2- to 6-year old females were underrepresented in<br />

15 | P age