Download your concert programme here - Barbican

Download your concert programme here - Barbican

Download your concert programme here - Barbican

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

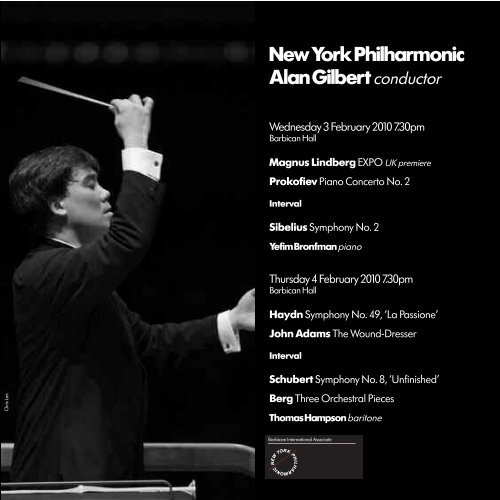

New York Philharmonic<br />

Alan Gilbert conductor<br />

Wednesday 3 February 2010 7.30pm<br />

<strong>Barbican</strong> Hall<br />

Magnus Lindberg EXPO UK premiere<br />

Prokofiev Piano Concerto No. 2<br />

Interval<br />

Sibelius Symphony No. 2<br />

Yefim Bronfman piano<br />

Thursday 4 February 2010 7.30pm<br />

<strong>Barbican</strong> Hall<br />

Haydn Symphony No. 49, ‘La Passione’<br />

John Adams The Wound-Dresser<br />

Interval<br />

Chris Lee<br />

Schubert Symphony No. 8, ‘Unfinished’<br />

Berg Three Orchestral Pieces<br />

Thomas Hampson baritone

Wednesday 3 February<br />

Magnus Lindberg (born 1958)<br />

EXPO (2009) UK premiere<br />

Magnus Lindberg, who is beginning a two-year<br />

appointment as the New York Philharmonic’s composer-inresidence,<br />

emerged on the international music scene in the<br />

1980s, one of a handful of Finnish composers of his<br />

generation that included Kaija Saariaho, Jouni Kaipainen,<br />

and Esa-Pekka Salonen. All four studied with the same<br />

teacher at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, the renowned<br />

composer and pedagogue Paavo Heininen. Lindberg also<br />

worked with another senior eminence of Finnish music, the<br />

composer Einojuhani Rautavaara.<br />

Lindberg and Salonen were close colleagues during their<br />

student years, and together they founded Toimii, an<br />

instrumental ensemble that not only championed modern<br />

music but also helped both composers investigate novel<br />

instrumental possibilities and compositional procedures.<br />

Lindberg was also active as a pianist, appearing in <strong>concert</strong><br />

and on recordings, especially in contemporary repertoire. In<br />

1981 he left Finland for Paris, w<strong>here</strong> he studied with Vinko<br />

Globokar and Gérard Grisey. Other formative training<br />

came from Franco Donatoni (in Siena), Brian Ferneyhough<br />

(in Darmstadt), and at the EMS Electronic Music Studio (in<br />

Stockholm). His work has been honoured with such awards<br />

as the UNESCO International Rostrum for Composers (1982<br />

and 1986), the Prix Italia (1986), the Nordic Council Music<br />

Prize (1988), the Royal Philharmonic Society Prize (1993) and<br />

the Wihuri Sibelius Prize (2003).<br />

During the 1980s Lindberg’s music revealed its composer’s<br />

penchant for complexity, a trait that led him to be<br />

uncompromising in the difficulties he sets before his<br />

musicians. ‘Only the extreme is interesting’, Lindberg<br />

proclaimed. ‘Striving for a balanced totality is nowadays an<br />

impossibility … an original mode of expression can only be<br />

achieved through the marginal – the hypercomplex<br />

combined with the primitive.’ As the decade unrolled,<br />

Lindberg grew increasingly preoccupied with the intricacies<br />

of rhythmic interaction on multiple levels; this led to the<br />

composition, in 1983, of his Zona for solo cello and chamber<br />

ensemble. Zona – Lindberg favours short, single-word titles –<br />

brought his investigations of rhythmic complexity to the<br />

practical limit of the unaided human mind, so for his next<br />

major work, the award-winning Kraft (for orchestra plus an<br />

ancillary ensemble that plays on both traditional musical<br />

instruments and such ‘found’ objects as chair legs and car<br />

springs), he devised a computer program to assist in<br />

generating more meticulous calculations to fuel his<br />

composition. Other computer programs would follow,<br />

always keeping up with advances in technology.<br />

In the course of music history, composers drawn towards<br />

stylistic complexity have often arrived at a breaking-point<br />

and then moved on to a soundworld that (at least from the<br />

outside) appears far simpler. Similarly, following the intense<br />

difficulty of Zona and Kraft Lindberg proceeded to<br />

2

Wednesday 3 February<br />

soundscapes that, in many cases, seem more relaxed and<br />

less insistently close to overload; some might even be<br />

described as smooth or spacious. That said, many of<br />

Lindberg’s scores, even those in the modern ‘classicist’<br />

mode, remain generally vigorous, colourful, dense and<br />

kinetic and, despite the extreme refinement of his<br />

compositional method, his scores manage to sound very<br />

spontaneous.<br />

Although he has worked in a variety of genres, Lindberg has<br />

carved out a particular reputation as a composer of<br />

orchestral music. ‘The orchestra’, he has declared, ‘is my<br />

favourite instrument.’ Symphonic works of the past decade<br />

or so include Feria (whose American premiere was given by<br />

the New York Philharmonic in 1997, conducted by Jukka-<br />

Pekka Saraste), a Concerto for Orchestra (2002) and<br />

<strong>concert</strong>os for cello (1999), clarinet (2002) and violin (2006).<br />

Among his most recent works is Seht die Sonne (‘Behold the<br />

Sun’), jointly commissioned by the Berlin Philharmonic and<br />

the San Francisco Symphony, and described in the Financial<br />

Times as ‘an extravagant and glittering piece on a grand<br />

scale’. These scores reveal Lindberg’s increasing interest in<br />

presenting clear-cut melody, sometimes even of a folkish tint,<br />

underscoring that even after composing some 80 works he<br />

continues to develop an idiosyncratic path of personal<br />

creative discovery.<br />

About EXPO – Magnus Lindberg’s first work written for the<br />

New York Philharmonic and also the first piece that Alan<br />

Gilbert conducted as the Orchestra’s Music Director, on<br />

16 September 2009 – the composer has offered the<br />

following thoughts:<br />

‘The title is self-explanatory; it’s the exposition of Alan’s<br />

season. I work with extremely strong contrasts, setting up<br />

some contrasts between super-fast and super-slow music<br />

and then a strange amalgam between these poles. It’s a<br />

piece built on qualities I find so gorgeous in Alan’s way of<br />

making music – absolute technical and physical straightness,<br />

no mystery around the rational part of it, and then on top of<br />

that the highly irrational and mysterious part of how you<br />

actually put music together.<br />

Given the brevity of the piece – 9 or 10 minutes – I thought a<br />

pithy word such as “EXPO” would make a fitting title;<br />

besides, I like the sound of the word. A work of any length<br />

must have a trajectory, a sense of direction and logic about<br />

the way it evolves. I have tried to establish a musical<br />

language to communicate this drama. As short as EXPO is,<br />

t<strong>here</strong> are more than 10 tempo markings, resulting in a<br />

feeling of great tension and energy in the orchestra.’<br />

Programme note © James M. Keller, New York Philharmonic<br />

Program Annotator<br />

3

Wednesday 3 February<br />

Sergey Prokofiev (1891–1953)<br />

Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 16 (1912–13)<br />

1 Andantino<br />

2 Scherzo: Vivace<br />

3 Intermezzo: Allegro moderato<br />

4 Allegro tempestoso<br />

Yefim Bronfman piano<br />

Prokofiev was a born show-off and a born competitor, and<br />

his music demonstrates that time and again – not necessarily<br />

in aggressive or unpleasant ways, though that side of his<br />

nature certainly surfaced from time to time, but rather in his<br />

fondness for telling stories, for casting magic spells, for<br />

demonstrating gymnastic, sporty and especially balletic<br />

prowess. Those are all qualities calculated to hold an<br />

audience in thrall, and they combined to make him a natural<br />

for the <strong>concert</strong>o medium.<br />

His Second Piano Concerto gives the fullest possible rein to<br />

all these gifts. He composed it in 1912–13, just before his<br />

graduation from the St Petersburg Conservatoire, primarily<br />

as a vehicle for his own virtuosity, and many would rate it by<br />

some distance the most technically demanding of all<br />

<strong>concert</strong>os in the standard repertoire. Though Prokofiev never<br />

admitted as much, it would not be surprising had he been<br />

deliberately aiming to outdo Rachmaninov’s massive Third<br />

Concerto, which was published and first performed in Russia<br />

in 1910. Prokofiev’s score was destroyed by fire at the time of<br />

the 1917–21 Civil War in the early days of Bolshevik rule. He<br />

reconstructed and reorchestrated it in his voluntary exile,<br />

during a stay in Bavaria in 1923.<br />

The deceptively lulling first theme is marked narrante<br />

(narrating), just as Rachmaninov’s plainer opening theme<br />

could easily have been. But this story proves to be not one of<br />

Rachmaninovian nostalgia and longing, nor of heroism and<br />

triumph, nor even one in which the soloist becomes<br />

emotionally embroiled. Rather it is in essence a fairytale,<br />

populated by larger- and stranger-than-life characters,<br />

unfolding in a world of mythical castles, potentates,<br />

hobgoblins and sundry grotesques. It asks us to suspend<br />

disbelief and look on in childlike awe.<br />

4

Wednesday 3 February<br />

The pianist is cast in the role of spell-master and illusionistin-chief,<br />

conjuring up undreamt-of beings and making<br />

them dance to his tunes, sometimes commanding the whole<br />

charade to cease so that he can take every role himself, as in<br />

the hypertrophic first-movement cadenza. Like the massive<br />

cadenza in the original version of Rachmaninov’s Third, this<br />

one occupies the structural place of a sonata recapitulation.<br />

The opening theme then closes the narrative frame,<br />

providing just a few seconds of calm for the soloist to<br />

regain composure.<br />

Then we are straight into a two-and-a-half-minute perpetualmotion<br />

Scherzo, consisting of no fewer than 1504 continuous<br />

semiquavers, challengingly laid out in parallel motion<br />

between the hands. Here the soloist doubles, in effect, as<br />

juggler and contortionist. The third movement is nominally an<br />

Intermezzo, but in character it comes across more like a<br />

grotesque march. Its extravagant gestures reminded<br />

Sviatoslav Richter of ‘a dragon devouring its young’, though<br />

when all is said and done perhaps this is only a pantomime<br />

dragon.<br />

For all the hand-flinging antics in the finale’s early stages, it<br />

contains more reflective episodes than the previous two<br />

movements. Two of these episodes have the makings of solo<br />

cadenzas, but neither grows to the monstrous dimensions of<br />

their counterpart in the first movement. Prokofiev was rarely<br />

one to strain himself unduly over such matters as structural<br />

transition, but the way he lets the second solo episode<br />

edge back towards the main theme is a compositional<br />

masterstroke. However, t<strong>here</strong> is nothing particularly subtle<br />

about the last few pages, which return us to the main business<br />

of neo-Lisztian acrobatics.<br />

Programme note © David Fanning<br />

INTERVAL<br />

5

Wednesday 3 February<br />

Jean Sibelius (1865–1957)<br />

Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 43 (1901–2)<br />

1 Allegretto<br />

2 Tempo andante, ma rubato<br />

3 Vivacissimo –<br />

4 Finale: Allegro moderato<br />

Sketches for the Second Symphony date back to Sibelius’s<br />

visit to Italy in early 1901. At the time he was contemplating<br />

various ambitious projects, none of which would come to<br />

fruition, including a four-movement tone-poem based on the<br />

Don Juan story and a setting of Dante’s Divina Commedia.<br />

His sketched ideas found their way instead into the slow<br />

movement of the symphony.<br />

The trip to Italy had come about at the suggestion of<br />

Sibelius’s friend, the amateur musician Axel Carpelan, who<br />

around this time raised money to allow Sibelius to relinquish<br />

his duties at the Helsinki Conservatoire and devote himself<br />

to the composition of the Second Symphony. When the<br />

composer returned to Finland for the summer and autumn<br />

of 1901, he still found the task an arduous one, but the work<br />

was essentially complete by November. Extensive revisions<br />

delayed the first performance (in Helsinki under the<br />

composer’s direction) first to January the following year, then<br />

again to 8 March. From that moment on, however, the<br />

symphony enjoyed unparalleled success in Finland, and it<br />

was soon to provide Sibelius with a major breakthrough in<br />

Germany, the kind of thing many Scandinavian composers<br />

(including Sibelius’s exact contemporary in Denmark, Carl<br />

Nielsen) craved, yet never achieved.<br />

Early reactions to the symphony read into it a portrayal of<br />

Finnish resistance to Russification. The country had indeed<br />

been under Russian rule since 1809, and the dispensation<br />

under the last of the Romanov tsars was far from liberal.<br />

Sibelius was certainly a good patriot and happy to voice his<br />

solidarity with national aspirations; and the defiant-heroic<br />

tone of his finale seems to invite extra-musical interpretation<br />

on these lines. Yet when Finnish commentators persisted as<br />

late as 1945 in writing of this as a ‘Liberation Symphony’, he<br />

issued emphatic disclaimers.<br />

What defines the originality of the work, and arguably has<br />

helped it retain its extraordinary popularity, is something<br />

more abstract, yet ultimately more potent, than any<br />

hypothetical political message, namely its exploratory<br />

6

Wednesday 3 February<br />

attitude to musical motion. This is at its most striking in the<br />

moderately paced first movement, which poses all sorts of<br />

questions and t<strong>here</strong>fore offers conductors considerable<br />

latitude in interpretation. Is the very opening an<br />

accompaniment or a theme, for example? Is its basic pulse<br />

defined by the steadily throbbing crotchets or by their<br />

broader melodic ascent? As the music unfolds, w<strong>here</strong> are the<br />

main points of structural articulation, apart from the<br />

extremely characteristic theme (first heard on declamatory<br />

woodwind) beginning with a long held note and ending in<br />

a flurry of short ones? Leaving all these issues undecided,<br />

the music evolves in an improvisatory succession of moods,<br />

rarely emotional or dramatic on the surface, but all in a<br />

state of becoming and carried along as though by forces<br />

of nature.<br />

The two central movements are again remarkable for their<br />

economy of means and concealed structural energy. The<br />

dark-hued slow movement is built around an introspective<br />

melody for bassoons (marked ‘lugubriously’) and quiet,<br />

chorale-like phrases in the strings, those ideas being spaced<br />

by more of the accelerations that have already marked the<br />

first movement.<br />

The scherzo then contrasts a whirlwind of agitated stringwriting<br />

with a heartfelt trio section led off by the oboe;<br />

displaying a fine instinct for symphonic proportion, Sibelius<br />

curtails this trio, so that its recurrence after the repeat of the<br />

scherzo will not sound jaded. Even more effectively, this<br />

recurrence leads straight on to the finale rather than back to<br />

a final statement of the scherzo – in broad terms following<br />

the model of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Now the<br />

redemptive tone promised by the quasi-religious ideas of the<br />

slow movement at last comes out into the open. And while the<br />

finale itself may be open to criticism for its relatively<br />

conventional imagery and structure, it is nothing if not bold in<br />

its attempt to measure up to Beethovenian (and other)<br />

precedents.<br />

Programme note © David Fanning<br />

7

Thursday 4 February<br />

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809)<br />

Symphony No. 49 in F minor, ‘La Passione’, Hob. I:49 (1768)<br />

1 Adagio<br />

2 Allegro di molto<br />

3 Menuet<br />

4 Finale: Presto<br />

Dated 1768, ‘La Passione’ is one of the most famous of a<br />

whole series of minor-mode Haydn symphonies from around<br />

1770. Some commentators have postulated – with no<br />

biographical evidence – that this outbreak of minor-key<br />

angst was prompted by a ‘romantic crisis’. In any case,<br />

Haydn was the least confessional of composers. Far more<br />

convincing is the notion that, like other composers, including<br />

J. B. Vanhal, Carlo d’Ordoñez (Austrian, despite his name)<br />

and the teenage Mozart (in his ‘little’ G minor Symphony,<br />

K183), Haydn was eager to explore the potential for tragic or<br />

stormy expression in a symphonic language that, thanks<br />

above all to Haydn himself, was rapidly developing in<br />

complexity and expressive power. This proliferation of minorkey<br />

symphonies has spawned the term Sturm und Drang<br />

(literally ‘Storm and Surge’, but more commonly rendered as<br />

‘Storm and Stress’), after a blood-and-thunder play on the<br />

American Revolution by Maximilian Klinger – a convenient<br />

enough stylistic label, though the official Sturm und Drang<br />

literary movement, kickstarted by Goethe’s rampaging 1773<br />

drama Götz von Berlichingen and his sensational novel Die<br />

Leiden des jungen Werther, lay in the future.<br />

‘La Passione’ is the last of Haydn’s symphonies to adopt the<br />

old sonata da chiesa (church sonata) pattern – ie, beginning<br />

with a slow movement. It is also his only symphony to retain<br />

the minor mode for each of the four movements; this,<br />

together with its lean, acerbic orchestral palette (strings plus<br />

oboes and horns, the latter used as a sombre or ominous<br />

backdrop), gives the work an almost unremitting bleakness.<br />

As with so many Haydn symphonies, the origins of the<br />

nickname are obscure, though one story has it that the work<br />

was first performed on Good Friday in the Esterházys’<br />

Eisenstadt palace. Certainly, the title fits the opening Adagio,<br />

with its mournful, burdened tread evocative of the via crucis.<br />

The initial motif (C–D flat–B flat–C) pervades each of the four<br />

movements, a pointer to Haydn’s growing interest in cyclic<br />

integration. The unexpected entry of the recapitulation,<br />

quietly reasserting F minor when the preceding bar led us to<br />

expect a chord of C minor, is paralleled by the underprepared<br />

recapitulations in both the second movement and<br />

the finale – all instances of Haydn’s sophisticated and (<strong>here</strong>)<br />

disquieting play with his listeners’ expectations.<br />

In the hectic, angular Allegro di molto, even more than in the<br />

Adagio, thematic development and variation spill far beyond<br />

the so-called ‘development’; as so often with Haydn, the<br />

recapitulation is not so much a restatement as a fiercely<br />

compressed reinterpretation of earlier events. The gravely<br />

beautiful Menuet has its own formal surprise in the 12-bar<br />

coda, which introduces a new sighing figure that deepens the<br />

mood of sorrowful resignation. By contrast, the trio, with its<br />

gleaming high horns, provides the one point of repose – and<br />

the sole appearance of F major – in the whole symphony.<br />

The driving, desperate finale revives the second movement’s<br />

Sturm und Drang with a laconic explosiveness of its own.<br />

Programme note © Richard Wigmore<br />

8

Thursday 4 February<br />

John Adams (born 1947)<br />

The Wound-Dresser (1988)<br />

Thomas Hampson baritone<br />

John Adams may have started out as a minimalist, but it has<br />

been a long time since he graduated from that description<br />

to become one of America’s most widely performed<br />

composers of <strong>concert</strong> music, a distinction he achieved thanks<br />

to a style in which musical richness and stylistic variety are<br />

deeply connected to the mainstream impetuses of classical<br />

music. He grew up studying clarinet and became so<br />

accomplished that he occasionally performed with the<br />

Boston Symphony Orchestra. At Harvard he studied<br />

composition with a starry list of teachers that included Leon<br />

Kirchner, Earl Kim, Roger Sessions, Harold Shapero, and<br />

David Del Tredici. After that, armed with a copy of John<br />

Cage’s book Silence (a graduation gift from his parents), he<br />

left the ‘eastern establishment’ for the relative aesthetic<br />

liberation of the West Coast. He arrived in California in 1971<br />

and has been based in the Bay Area ever since. During his<br />

first decade t<strong>here</strong> Adams explored an evolving fascination<br />

with the repetitive momentum of minimalism, but by 1981 he<br />

was describing himself as ‘a minimalist who is bored with<br />

minimalism’.<br />

Among Adams’s most internationally acclaimed works are<br />

his operas, which characteristically address the personal<br />

stories behind momentous political or historical events: Nixon<br />

in China (1987, which considers Richard Nixon’s historic 1972<br />

meeting with Mao Tse-tung), The Death of Klinghoffer (1990,<br />

inspired by the hijacking, five years earlier, of the cruise ship<br />

Achille Lauro), I Was Looking at the Ceiling and Then I Saw<br />

the Sky (1995, a ‘song play’ set in the aftermath of the 1994<br />

Los Angeles earthquake), and Doctor Atomic (premiered in<br />

2005, involving the testing of the first atomic bomb, and<br />

which Alan Gilbert led to great acclaim at the Metropolitan<br />

Opera in 2008). Adams’s most recent opera, A Flowering<br />

Tree (2006), returns to more classic operatic territory, setting<br />

a South Indian folktale that involves personal transformations<br />

and moral choices. In some of these scores, as in many of his<br />

instrumental compositions, one finds the confluence of<br />

popular and classical styles, the mixing of high and low<br />

aesthetics, which reflects the breadth of his inspiration and his<br />

comprehensive language.<br />

In 2003 Adams succeeded Pierre Boulez as composer-inresidence<br />

at Carnegie Hall, remaining in the post until 2007,<br />

and in 2009 he became creative chair of the Los Angeles<br />

Philharmonic. In addition to his activities as a composer, he<br />

has grown increasingly active as a conductor, and has led<br />

9

Thursday 4 February<br />

many of the world’s most distinguished orchestras in<br />

<strong>programme</strong>s that mix his own works with compositions by<br />

figures as diverse as Debussy, Stravinsky, Ravel, Zappa, Ives,<br />

Reich, Glass and Ellington. The New York Philharmonic<br />

spotlighted him in a Composer’s Week dedicated to his music<br />

in 1997, but for many listeners his most memorable<br />

connection with the orchestra was the unveiling of his On the<br />

Transmigration of Souls, a meditation on the attacks of 11<br />

September, 2001, which the orchestra co-commissioned and<br />

then premiered at the outset of the 2002 season, and whose<br />

subsequent recording won three Grammy awards, while the<br />

work itself garnered a Pulitzer Prize for its composer.<br />

In 2008 John Adams published Hallelujah Junction, a<br />

compelling book of memoirs and commentary on American<br />

musical life. T<strong>here</strong>, we read that The Wound-Dresser ‘began<br />

as a plan to set prose cameos from Walt Whitman’s account<br />

of his Civil War days in [his prose collection] Specimen Days’.<br />

The texts, which involved Whitman’s service in military<br />

hospitals, ‘made me think of the stories I had heard from San<br />

Francisco friends, many of them gay, who had lost partners<br />

and loved ones to the plague of AIDS that, in 1989, was still<br />

devastating the country’. They also related to ‘the memory of<br />

a more personal story, that of the long, slow decline of my<br />

father from Alzheimer’s disease … [and] my mother’s<br />

struggle and the devotion with which she nursed him’.<br />

‘Instead of setting Specimen Days’, he reported, ‘I chose The<br />

Wound-Dresser, a poem that is both graphic and tender,<br />

perhaps the most intimate recollection of what Whitman<br />

experienced in his years of selfless work as a nurse and<br />

caregiver in the hospitals that surrounded wartime<br />

Washington.’<br />

Programme note © James M. Keller, New York Philharmonic<br />

Program Annotator<br />

INTERVAL<br />

10

Thursday 4 February<br />

The Wound-Dresser<br />

Bearing the bandages, water and sponge,<br />

Straight and swift to my wounded I go,<br />

W<strong>here</strong> they lie on the ground after the battle brought in,<br />

W<strong>here</strong> their priceless blood reddens the grass the ground,<br />

Or to the rows of the hospital tent, or under the roof’d<br />

hospital,<br />

To the long rows of cots up and down each side I return,<br />

To each and all one after another I draw near, not one do<br />

I miss,<br />

An attendant follows holding a tray, he carries a refuse pail,<br />

Soon to be fill’d with clotted rags and blood, emptied, and<br />

fill’d again.<br />

I onward go, I stop,<br />

With hinged knees and steady hand to dress wounds,<br />

I am firm with each, the pangs are sharp yet unavoidable,<br />

One turns to me his appealing eyes – poor boy! I never<br />

knew you,<br />

Yet I think I could not refuse this moment to die for you, if that<br />

would save you.<br />

On, on I go, (open doors of time! open hospital doors!)<br />

The crush’d head I dress (poor crazed hand tear not the<br />

bandage away),<br />

The neck of the cavalry-man with the bullet through and<br />

through I examine,<br />

Hard the breathing rattles, quite glazed already the eye,<br />

yet life struggles hard,<br />

(Come sweet death! be persuaded O beautiful death!<br />

In mercy come quickly.)<br />

I dress a wound in the side, deep, deep,<br />

But a day or two more, for see the frame all wasted<br />

and sinking,<br />

And the yellow-blue countenance see.<br />

I dress the perforated shoulder, the foot with the<br />

bullet-wound,<br />

Cleanse the one with a gnawing and putrid gangrene,<br />

so sickening, so offensive,<br />

While the attendant stands behind aside me holding the tray<br />

and pail.<br />

I am faithful, I do not give out,<br />

The fractur’d thigh, the knee, the wound in the abdomen,<br />

These and more I dress with impassive hand, (yet deep in my<br />

breast a fire, a burning flame.)<br />

Thus in silence in dreams’ projections,<br />

Returning, resuming, I thread my way through the hospitals,<br />

The hurt and wounded I pacify with soothing hand,<br />

I sit by the restless all the dark night, some are so young,<br />

Some suffer so much, I recall the experience sweet and sad,<br />

(Many a soldier’s loving arms about this neck have cross’d<br />

and rested,<br />

Many a soldier’s kiss dwells on these bearded lips.)<br />

Walt Whitman (1819–92)<br />

From the stump of the arm, the amputated hand,<br />

I undo the clotted lint, remove the slough, wash off the matter<br />

and blood,<br />

Back on his pillow the soldier bends with curv’d neck and<br />

side-falling head,<br />

His eyes are closed, his face is pale, he dares not look on the<br />

bloody stump,<br />

And has not yet look’d on it.<br />

11

Thursday 4 February<br />

Franz Schubert (1797–1828)<br />

Symphony No. 8 in B minor, ‘Unfinished’, D759 (1822)<br />

1 Allegro moderato<br />

2 Andante con moto<br />

The years 1818 to 1822–3 were critical ones for Schubert,<br />

creatively and personally. Between February 1818, the month<br />

he completed his Sixth Symphony, and November 1822,<br />

when he embarked on the ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy, he began<br />

and abandoned nearly a dozen large-scale instrumental<br />

works, including the Quartettsatz, D703, and four<br />

symphonies. The most celebrated of these, and the world’s<br />

most famous symphonic torso, is the so-called ‘Unfinished’,<br />

begun in the autumn of 1822 and then set aside at the<br />

beginning of November.<br />

The symphony is shrouded in mystery. Schubert, whose fame<br />

as a writer of songs and partsongs was rapidly growing,<br />

composed it to no commission, with no immediate prospect<br />

of performance, and never mentioned it in his<br />

correspondence. The reasons why he abandoned the score<br />

after orchestrating two movements and sketching a scherzo<br />

and trio have been endlessly debated. Perhaps the<br />

symphony’s non-completion can be attributed to the creative<br />

crisis of 1818–22, when so many torsos testify to Schubert’s<br />

struggles to reconcile the challenge of Beethoven’s middleperiod<br />

works with his own increasingly daring, subjective<br />

vision. According to this theory, after finishing two sublime<br />

movements he was dissatisfied with the scherzo and daunted<br />

by the Beethovenian challenge of creating a finale worthy of<br />

the two completed movements. Or perhaps, as several<br />

biographers have argued, the answer lies in the syphilitic<br />

illness Schubert contracted during the winter of 1822–3 and<br />

its attendant physical and emotional traumas. What we do<br />

know is that in 1823 Schubert passed the manuscript to his<br />

friend Josef Hüttenbrenner, in gratitude for the Diploma of<br />

Honour awarded, at Hüttenbrenner’s behest, by the Styrian<br />

Music Society in Graz. The symphony remained in the<br />

possession of Josef and, subsequently, his brother Anselm,<br />

unknown to the world, until 1865, when the conductor Johann<br />

Herbeck gave the premiere in a <strong>concert</strong> of the Vienna<br />

Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde.<br />

None of Schubert’s earlier instrumental works approaches<br />

the despairing, almost confessional tone of this, the first great<br />

Romantic symphony. The tragic atmosp<strong>here</strong> of the Allegro<br />

moderato is immediately established by the brooding ‘motto’<br />

theme announced pianissimo by unison cellos and basses –<br />

a darkly haunting symphonic opening distantly presaged by<br />

Haydn’s Symphony No. 103, the ‘Drum Roll’. The mood<br />

brightens with the famous ‘second subject’, a transfigured<br />

waltz sounded on the cellos against repeated syncopations<br />

on violas and clarinets. But the idyll is quickly shattered by<br />

volcanic eruptions from the full orchestra and a passage of<br />

strenuous imitation on a phrase from the waltz theme. At the<br />

opening of the development Schubert works the motto into<br />

a protracted, yearning crescendo that generates the most<br />

apocalyptic climax in all his symphonies. The recapitulation<br />

omits the motto, which only returns, with inspired dramatic<br />

timing, at the start of the coda.<br />

After the first movement’s Stygian close, the luminous main<br />

theme of the E major Andante con moto, preceded and<br />

punctuated by a refrain for bassoons, horns and pizzicato<br />

basses, comes as a profound solace. Although the music is<br />

later threatened by tumultuous outbursts so characteristic of<br />

Schubert’s later slow movements, the dominant mood is one<br />

of mysterious serenity. In one of the composer’s most magical<br />

harmonic strokes, the coda conjures an unearthly vision of<br />

A flat major, ppp, before the music glides gently back to the<br />

home key for the tranquil close.<br />

Programme note © Richard Wigmore<br />

12

Thursday 4 February<br />

Alban Berg (1885–1935)<br />

Three Orchestral Pieces, Op. 6 (1913–15)<br />

1 Präludium: Langsam<br />

2 Reigen: Anfangs etwas zögernd – Leicht beschwingt<br />

3 Marsch: Mässiges Marschtempo<br />

Alban Berg did not get off to a promising start. A terrible<br />

student: he had to repeat two separate years of high school<br />

before he could finally graduate. Then, too, a fling with the<br />

family’s kitchen maid led to his becoming a father at the age<br />

of 17. Though passionate about music, he was clearly not cut<br />

out for academic success, and sensibly accepted a position<br />

as an unpaid intern in the civil service.<br />

The decisive step in his eventual career arrived in the<br />

autumn of 1904, when he and Anton Webern signed up for<br />

composition lessons with Arnold Schoenberg, who had<br />

taken out a newspaper advertisement in the hope of<br />

attracting pupils. Schoenberg, who was a little more than<br />

10 years older than Berg and not yet famous, stopped<br />

offering formal classes after a year, frustrated that most of<br />

his pupils showed no aptitude for composition. However,<br />

the talented students – including both Webern and Berg –<br />

stuck with him. Schoenberg seems not to have insisted that<br />

his students adopt his own compositional methods; in<br />

the event, both Webern and Berg developed strikingly<br />

individual voices. Some years later, Webern would write<br />

of Schoenberg’s tutelage:<br />

‘People think Schoenberg teaches his own style and forces<br />

the pupil to adopt it. That is quite untrue – Schoenberg<br />

teaches no style of any kind, he preaches the use neither of<br />

old artistic resources nor of new ones … Schoenberg<br />

demands, above all, that what the pupil writes for his lessons<br />

should not consist of any old notes written down to fill out an<br />

academic form, but should be something achieved as the<br />

result of his need for self-expression. So he must, in fact,<br />

create – even in the musical examples written during the most<br />

primitive initial stages. Whatever Schoenberg explains with<br />

reference to his pupil’s work arises organically from the work<br />

itself; he never has recourse to extraneous theoretical<br />

maxims.’<br />

Berg’s formal studies with Schoenberg continued through<br />

1911. Writing to his publisher in 1911, Schoenberg remarked:<br />

‘Alban Berg is an extraordinarily gifted composer, but the<br />

state he was in when he came to me was such that his<br />

imagination apparently could not work on anything but<br />

Lieder … He was absolutely incapable of writing an<br />

instrumental movement or inventing an instrumental theme.’<br />

13

Thursday 4 February<br />

That shortcoming had been rectified by the time Berg<br />

composed his Three Orchestral Pieces in 1913–15, a work<br />

that demonstrates his fluency in manipulating a huge<br />

orchestra toward an expressive end. The direct inspiration<br />

seems to have come from the premiere of Mahler’s Ninth<br />

Symphony in June 1912, at which Berg was present. One<br />

might fairly say that he picked up w<strong>here</strong> Mahler left off;<br />

Berg’s Three Orchestral Pieces takes Mahlerian<br />

transformation and exaggeration to an extreme, all overlaid<br />

on a structure of traditional dance-types, such as ländler,<br />

waltz and march.<br />

Everything is meticulously organised in these complex<br />

movements, which are unified by the careful interweaving of<br />

thematic material. The combined duration of the first two<br />

pieces perfectly balances that of the third. In fact, the first two<br />

movements were premiered as a pair, with the March only<br />

joining them in performance seven years later; even the<br />

printed score allows that the first two movements may be<br />

presented without the third.<br />

Berg had hoped to present the set on Schoenberg’s 40th<br />

birthday, which fell on 13 September, 1914. But the work<br />

progressed slowly. ‘I keep asking myself, again and again’,<br />

he wrote to his mentor, ‘whether what I express [in this<br />

piece], often brooding over certain bars for days on end,<br />

is any better than my last things.’ At least the first and<br />

third pieces were ready in time, and Berg offered them to<br />

his teacher along with a letter that speaks volumes about<br />

their relationship:<br />

‘My hope to write something … I could dedicate to you<br />

without incurring <strong>your</strong> displeasure has been repeatedly<br />

disappointed for several years … I cannot tell today whether I<br />

have succeeded or failed. Should the latter be the case, then<br />

in <strong>your</strong> fatherly benevolence, Mr Schoenberg, you must take<br />

the goodwill for the deed.’<br />

Programme note © James M. Keller, New York Philharmonic<br />

Program Annotator<br />

14

about the performers<br />

About the performers<br />

Hayley Sparks<br />

Alan Gilbert conductor<br />

Alan Gilbert began his tenure as Music<br />

Director of the New York Philharmonic<br />

in September 2009, the first native<br />

New Yorker to hold the post. For his<br />

inaugural season he has introduced a<br />

number of new initiatives and artistic<br />

partners: The Marie-Josée Kravis<br />

composer-in-residence, held by<br />

Magnus Lindberg, and artist-inresidence,<br />

held by Thomas Hampson;<br />

an annual three-week festival; and<br />

CONTACT!, the New York<br />

Philharmonic’s new-music series. This<br />

season he led the orchestra on a major<br />

tour of Asia, with debuts in Hanoi and<br />

Abu Dhabi, and he gives world,<br />

American and New York premieres.<br />

Also this season he takes up the first<br />

William Schuman Chair in Musical<br />

Studies at the Juilliard School, a<br />

position that includes coaching,<br />

conducting and performance<br />

masterclasses.<br />

Highlights of last season with the<br />

New York Philharmonic included the<br />

Bernstein anniversary <strong>concert</strong> at<br />

Carnegie Hall and a performance<br />

with the Juilliard Orchestra. In May last<br />

year Alan Gilbert conducted the world<br />

premiere of Peter Lieberson’s The<br />

World in Flower, a New York<br />

Philharmonic commission, and in July<br />

he led the New York Philharmonic<br />

Concerts in the Parks and Free Indoor<br />

Concerts, as well as giving <strong>concert</strong>s at<br />

the Bravo! Vail Valley Music Festival<br />

in Colorado.<br />

In June 2008 he became conductor<br />

laureate of the Royal Stockholm<br />

Philharmonic Orchestra, following his<br />

final <strong>concert</strong> as its chief conductor and<br />

artistic advisor. He has been principal<br />

guest conductor of Hamburg’s NDR<br />

Symphony Orchestra since 2004. He<br />

regularly conducts other leading<br />

orchestras in America and<br />

internationally, including the Boston,<br />

Chicago and San Francisco Symphony<br />

orchestras, the Cleveland and<br />

Philadelphia orchestras, the Berlin<br />

Philharmonic Orchestra, the Bavarian<br />

Radio Symphony Orchestra,<br />

Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw<br />

Orchestra, and Orchestre National de<br />

Lyon. In 2003 he was named the first<br />

music director of Santa Fe Opera.<br />

Alan Gilbert studied at Harvard<br />

University, the Curtis Institute of Music<br />

and the Juilliard School. He was<br />

assistant conductor of the Cleveland<br />

Orchestra from 1995 to 1997. In<br />

November 2008 he made his<br />

acclaimed Metropolitan Opera<br />

debut, conducting John Adams’s<br />

Doctor Atomic.<br />

His recording of Prokofiev’s Scythian<br />

Suite with the Chicago Symphony<br />

Orchestra was nominated for a<br />

Grammy Award in 2008, while his CD<br />

of Mahler’s Symphony No. 9 received<br />

acclaim from the Chicago Tribune and<br />

Gramophone magazine.<br />

15

about the performers<br />

Dario Costa<br />

Yefim Bronfman piano<br />

Yefim Bronfman is widely regarded<br />

as one of the leading virtuoso pianists<br />

performing today. His commanding<br />

technique and exceptional lyrical gifts<br />

have won him consistent critical<br />

acclaim and enthusiastic audiences<br />

worldwide, whether for his solo<br />

recitals, his orchestral engagements<br />

or his rapidly growing catalogue<br />

of recordings.<br />

Orchestral highlights this season<br />

include two performances at the<br />

Tanglewood Festival with the Boston<br />

Symphony Orchestra under James<br />

Levine and Michael Tilson Thomas; an<br />

appearance at the Lucerne Festival<br />

with the Philharmonia Orchestra and<br />

Esa-Pekka Salonen, followed by<br />

<strong>concert</strong>s with the Philharmonia and<br />

Christoph von Dohnányi performing<br />

both Brahms piano <strong>concert</strong>os; multiple<br />

<strong>concert</strong>s with the Vienna Philharmonic<br />

with Zubin Mehta and the Lucerne<br />

Academy Orchestra with Pierre<br />

Boulez; ‘Artiste Étoile’ at the Lucerne<br />

Festival; a recital tour throughout<br />

Japan; and subscription <strong>concert</strong>s with<br />

the Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles<br />

Philharmonic and Philadelphia and<br />

Cleveland orchestras.<br />

Recitals and duos in 2009–10 include<br />

appearances at New York’s Carnegie<br />

Hall; a recital tour of 10 American cities<br />

and performances in Rome, Vienna<br />

and Warsaw.<br />

Born in Tashkent in the Soviet Union in<br />

1958, Yefim Bronfman emigrated to<br />

Israel with his family in 1973, w<strong>here</strong> he<br />

studied with pianist Arie Vardi, head of<br />

the Rubin Academy of Music at Tel Aviv<br />

University. In the USA, he studied at the<br />

Juilliard School, Marlboro, and the<br />

Curtis Institute of Music, and with<br />

Rudolf Firkušný, Leon Fleisher and<br />

Rudolf Serkin. Yefim Bronfman<br />

became an American citizen in 1989.<br />

16

about the performers<br />

Dario Costa<br />

Thomas Hampson baritone<br />

This season Thomas Hampson serves<br />

as both artist-in-residence and<br />

Leonard Bernstein scholar-in-residence<br />

at the New York Philharmonic. In these<br />

roles he will sing three <strong>programme</strong>s<br />

with the orchestra, appear on the<br />

orchestra’s current European tour,<br />

give a recital in Alice Tully Hall, and<br />

present three lectures as part of the<br />

Orchestra’s ‘Insights’ Series.<br />

The renowned American baritone has<br />

performed in the world’s pre-eminent<br />

<strong>concert</strong> halls and opera houses and<br />

with many of today’s leading musicians<br />

and orchestras; he also maintains an<br />

active interest in teaching, music<br />

research and technology. An important<br />

interpreter of German Lieder, he is also<br />

known as a leading proponent of the<br />

study of American song through his<br />

Hampsong Foundation, which he<br />

founded in 2003.<br />

In addition to his work with the New<br />

York Philharmonic, much of Thomas<br />

Hampson’s 2009–10 season is devoted<br />

to his ‘Song of America’ project.<br />

Collaborating with the Library of<br />

Congress, he is giving recitals and<br />

broadcasts and presenting<br />

masterclasses, educational activities<br />

and exhibitions across the country and<br />

through a new interactive online<br />

resource, www.songofamerica.net.<br />

Other engagements include<br />

Mendelssohn’s Elijah with Kurt Masur<br />

in Leipzig; Verdi’s Ernani and<br />

Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with<br />

Zurich Opera; Verdi’s La traviata at the<br />

Metropolitan Opera; solo recitals<br />

throughout the USA and in many<br />

European capitals; and the galas of<br />

the Vienna Staatsoper and the new<br />

Winspear Opera House in Dallas.<br />

Raised in Spokane, Washington,<br />

Thomas Hampson has an awardwinning<br />

discography of more than<br />

150 CDs. He has been named<br />

Kammersänger of the Vienna<br />

Staatsoper, Chevalier de l’Ordre des<br />

Arts et des Lettres by the Republic of<br />

France; and Special Advisor to the<br />

Study and Performance of Music in<br />

America by Dr James H. Billington,<br />

Librarian of Congress.<br />

17

about the performers<br />

New York Philharmonic<br />

Founded in 1842, the New York<br />

Philharmonic is the oldest symphony<br />

orchestra in the USA and one of the<br />

oldest in the world. Since its inception,<br />

the Philharmonic has played a<br />

leading role in American musical life,<br />

championing the new music of its time<br />

and commissioning or premiering<br />

many important works, from Dvořák’s<br />

Symphony No. 9 and Gershwin’s An<br />

American in Paris (1928) to John<br />

Adams’s Pulitzer Prize-winning On the<br />

Transmigration of Souls and Esa-Pekka<br />

Salonen’s Piano Concerto.<br />

Alan Gilbert became Music Director at<br />

the start of this season, succeeding<br />

Lorin Maazel in a distinguished line of<br />

musicians that has included Kurt<br />

Masur, Leonard Bernstein, Zubin<br />

Mehta, Pierre Boulez, Gustav Mahler,<br />

Bruno Walter and Arturo Toscanini.<br />

Over the past century the Philharmonic<br />

has become renowned around the<br />

globe, having appeared in 429 cities in<br />

61 countries on five continents. In<br />

February 2008 the Philharmonic made<br />

a historic visit to Pyongyang,<br />

Democratic People’s Republic of Korea<br />

– the first performance t<strong>here</strong> by an<br />

American orchestra and for which the<br />

Philharmonic received the 2008<br />

Common Ground Award for Cultural<br />

Diplomacy.<br />

Long a media pioneer, the orchestra<br />

began radio broadcasts in 1922, and is<br />

currently represented by The New York<br />

Philharmonic This Week, syndicated<br />

nationally 52 weeks per year, streamed<br />

on the orchestra’s website, nyphil.org,<br />

and carried on Sirius XM Radio.<br />

On television, in the 1950s and 1960s,<br />

the orchestra inspired a generation of<br />

music lovers through Leonard<br />

Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts,<br />

telecast on CBS, and its presence on<br />

television has continued with annual<br />

appearances on Live from Lincoln<br />

Center. The internet has expanded the<br />

orchestra’s reach still further, and in<br />

2006 it became the first major<br />

American orchestra to offer<br />

downloadable <strong>concert</strong>s, recorded live;<br />

and in November 2009, became the<br />

first orchestra to offer an iTunes Pass.<br />

Credit Suisse, the exclusive global<br />

sponsor of the New York Philharmonic,<br />

supports the orchestra’s activities at<br />

home in New York, nationally in the<br />

USA, and around the world. The<br />

current European tour will be the fifth<br />

one under the aegis of Credit Suisse,<br />

and the second in Europe.<br />

NEW YORK<br />

PHILHARMONIC<br />

18

about the performers<br />

Alan Schindler<br />

19

about the performers<br />

New York Philharmonic<br />

Music Director<br />

Alan Gilbert<br />

Assistant Conductor<br />

Daniel Boico<br />

Laureate Conductor<br />

1943–90<br />

Leonard Bernstein<br />

Music Director Emeritus<br />

Kurt Masur<br />

Violin<br />

Glenn Dicterow Concertmaster<br />

The Charles E. Culpeper Chair<br />

Sheryl Staples Principal<br />

Associate Concertmaster<br />

The Elizabeth G. Beinecke Chair<br />

Michelle Kim<br />

Assistant Concertmaster<br />

The William Petschek Family Chair<br />

Enrico Di Cecco<br />

Carol Webb<br />

Yoko Takebe<br />

Minyoung Chang<br />

Hae-Young Ham<br />

The Mr and Mrs Timothy M. George<br />

Chair<br />

Lisa GiHae Kim +<br />

Kuan-Cheng Lu<br />

Newton Mansfield<br />

Kerry McDermott<br />

Anna Rabinova<br />

Charles Rex<br />

The Shirley Bacot Shamel Chair<br />

Fiona Simon<br />

Sharon Yamada<br />

Elizabeth Zeltser +<br />

Yulia Ziskel +<br />

Marc Ginsberg Principal<br />

Lisa Kim *<br />

In memory of Laura Mitchell<br />

Soohyun Kwon<br />

The Joan and Joel I. Picket Chair<br />

Duoming Ba<br />

Mark Schmoockler +<br />

Na Sun<br />

Vladimir Tsypin<br />

Stephanie Jeong ++<br />

Shan Jiang ++<br />

Marta Krechkovsky ++<br />

Krzysztof Kuznik ++<br />

Setsuko Nagata ++<br />

Sarah O’Boyle ++<br />

Suzanne Ornstein ++<br />

Jungsun Yoo ++<br />

Viola<br />

Cynthia Phelps Principal<br />

The Mr and Mrs Frederick P. Rose Chair<br />

Rebecca Young *+<br />

Irene Breslaw **<br />

The Norma and Lloyd Chazen Chair<br />

Dorian Rence<br />

Katherine Greene<br />

The Mr and Mrs William J. McDonough<br />

Chair<br />

Dawn Hannay<br />

Vivek Kamath<br />

Peter Kenote<br />

Barry Lehr<br />

Kenneth Mirkin +<br />

Judith Nelson<br />

Robert Rinehart<br />

The Mr and Mrs G. Chris Andersen Chair<br />

Maurycy Banaszek ++<br />

Mark Holloway ++<br />

Cello<br />

Carter Brey Principal<br />

The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Chair<br />

Eileen Moon *<br />

The Paul and Diane Guenther Chair<br />

Qiang Tu<br />

The Shirley and Jon Brodsky Foundation<br />

Chair<br />

Evangeline Benedetti<br />

Eric Bartlett<br />

The Mr and Mrs James E. Buckman Chair<br />

Elizabeth Dyson<br />

Maria Kitsopoulos<br />

Sumire Kudo<br />

Ru-Pei Yeh<br />

Wei Yu<br />

Susan Babini ++<br />

Wilhelmina Smith ++<br />

Double Bass<br />

Eugene Levinson Principal<br />

The Redfield D. Beckwith Chair<br />

Orin O’Brien<br />

Acting Associate Principal<br />

The Herbert M. Citrin Chair<br />

William Blossom<br />

The Ludmila S. and Carl B. Hess Chair<br />

Randall Butler<br />

David J. Grossman<br />

Satoshi Okamoto<br />

Joel Braun ++<br />

Stephen Sas ++<br />

Rion Wentworth ++<br />

Marilyn Dubow<br />

The Sue and Eugene Mercy, Jr Chair<br />

Martin Eshelman<br />

Quan Ge<br />

Judith Ginsberg +<br />

Myung-Hi Kim +<br />

Hanna Lachert<br />

Hyunju Lee<br />

Daniel Reed<br />

20

about the performers<br />

Flute<br />

Robert Langevin Principal<br />

The Lila Acheson Wallace Chair<br />

Sandra Church *+<br />

Renée Siebert<br />

Mindy Kaufman<br />

Alexandra Sopp ++<br />

Piccolo<br />

Mindy Kaufman<br />

Oboe<br />

Liang Wang Principal<br />

The Alice Tully Chair<br />

Sherry Sylar *+<br />

Robert Botti<br />

Acting Associate Principal<br />

Robert Botti<br />

Keisuke Ikuma ++<br />

Cor Anglais<br />

Thomas Stacy<br />

The Joan and Joel Smilow Chair<br />

Clarinet<br />

Mark Nuccio Acting Principal<br />

The Edna and W. Van Alan Clark Chair<br />

Pascual Martinez Forteza<br />

Acting Associate Principal<br />

The Honey M. Kurtz Family Chair<br />

Alucia Scalzo ++<br />

Amy Zoloto ++<br />

Jonathan Gunn ++<br />

E flat Clarinet<br />

Pascual Martinez Forteza<br />

Bass Clarinet<br />

Amy Zoloto ++<br />

Bassoon<br />

Judith LeClair Principal<br />

The Pels Family Chair<br />

Kim Laskowski *<br />

Roger Nye<br />

Arlen Fast<br />

Contrabassoon<br />

Arlen Fast<br />

Horn<br />

Philip Myers Principal<br />

The Ruth F. and Alan J. Broder Chair<br />

Erik Ralske<br />

Acting Associate Principal<br />

R. Allen Spanjer<br />

Howard Wall<br />

Cara Kizer ++<br />

David Smith ++<br />

Chad Yarbrough ++<br />

Trumpet<br />

Philip Smith Principal<br />

The Paula Levin Chair<br />

Matthew Muckey *<br />

Ethan Bensdorf<br />

Thomas V. Smith<br />

Trombone<br />

Joseph Alessi Principal<br />

The Gurnee F. and Marjorie L. Hart Chair<br />

Amanda Stewart *<br />

David Finlayson<br />

The Donna and Benjamin M. Rosen<br />

Chair<br />

Bass Trombone<br />

James Markey<br />

Tuba<br />

Alan Baer Principal<br />

Timpani<br />

Markus Rhoten Principal<br />

The Carlos Moseley Chair<br />

Peter Wilson ++<br />

Percussion<br />

Christopher S. Lamb Principal<br />

The Constance R. Hoguet Friends of the<br />

Philharmonic Chair<br />

Daniel Druckman *<br />

The Mr and Mrs Ronald J. Ulrich Chair<br />

Erik Charlston ++<br />

David DePeters ++<br />

Joseph Tompkins ++<br />

Harp<br />

Nancy Allen Principal<br />

The Mr and Mrs William T. Knight III Chair<br />

June Han ++<br />

Keyboard section:<br />

In memory of Paul Jacobs<br />

Harpsichord<br />

Lionel Party +<br />

Paolo Bordignon ++<br />

Piano<br />

The Karen and Richard S. LeFrak Chair<br />

Harriet Wingreen +<br />

Jonathan Feldman +<br />

Elizabeth DiFelice ++<br />

Organ<br />

Kent Tritle +<br />

Librarians<br />

Lawrence Tarlow Principal<br />

Sandra Pearson **+<br />

Sara Griffin **<br />

Orchestra Personnel<br />

Manager<br />

Carl R. Schiebler<br />

Stage Representative<br />

Louis J. Patalano<br />

Stage Crew<br />

Fernando Carpio<br />

Joseph Faretta<br />

Robert W. Pierpont<br />

Michael Pupello<br />

Audio Director<br />

Lawrence Rock<br />

* Associate Principal<br />

** Assistant Principal<br />

+ On Leave<br />

++ Replacement/Extra<br />

The New York Philharmonic uses<br />

the revolving seating method for<br />

section string players who are<br />

listed alphabetically in the roster.<br />

21

about the performers<br />

New York Philharmonic<br />

Honorary Members of the<br />

Society<br />

Pierre Boulez<br />

Stanley Drucker<br />

Lorin Maazel<br />

Zubin Mehta<br />

Carlos Moseley<br />

Chairman, Board of<br />

Directors<br />

Gary W. Parr<br />

President and Executive<br />

Director<br />

Zarin Mehta<br />

ADMINISTRATION<br />

Vice President,<br />

Communications<br />

Eric Latzky<br />

Vice President,<br />

Operations<br />

Miki Takebe<br />

Artistic Administrator<br />

John Mangum<br />

Orchestra Personnel<br />

Assistant/Auditions<br />

Coordinator<br />

Nishi Badhwar<br />

Tour Physician<br />

Dr John Cahill<br />

Operations Assistant<br />

James Eng<br />

Assistant to the Music<br />

Director<br />

Joliene R. Ford<br />

Associate Director,<br />

Information Technology<br />

Elizabeth Lee<br />

Operations Manager<br />

Brendan Timins<br />

Instruments made possible, in<br />

part, by The Richard S. and<br />

Karen LeFrak Endowment Fund.<br />

Programmes of the New York<br />

Philharmonic are supported, in<br />

part, by public funds from the<br />

New York State Council on the<br />

Arts, New York City Department<br />

of Cultural Affairs, and the<br />

National Endowment of the Arts.<br />

Programme produced by Harriet Smith; printed by Sharp Print Limited;<br />

advertising by Cabbell (tel. 020 8971 8450)<br />

Please make sure that all digital watch alarms and mobile phones are switched off during the<br />

performance. In accordance with the requirements of the licensing authority, sitting or standing<br />

in any gangway is not permitted. Smoking is not permitted anyw<strong>here</strong> on the <strong>Barbican</strong> premises.<br />

No eating or drinking is allowed in the auditorium. No cameras, tape recorders or any other<br />

recording equipment may be taken into the hall.<br />

<strong>Barbican</strong> Centre<br />

Silk Street, London EC2Y 8DS<br />

Administration 020 7638 4141<br />

Box Office 020 7638 8891<br />

Great Performers Last-Minute Concert<br />

Information Hotline 0845 120 7505<br />

www.barbican.org.uk<br />

22