Black Stain Root Disease - USDA Forest Service - U.S. Department ...

Black Stain Root Disease - USDA Forest Service - U.S. Department ...

Black Stain Root Disease - USDA Forest Service - U.S. Department ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Black</strong> <strong>Stain</strong> <strong>Root</strong> <strong>Disease</strong><br />

Mortality centers in pinyon<br />

Pathogen—<strong>Black</strong> stain root disease is caused by the fungus Leptographium wageneri var. wageneri. This variety<br />

infects only pinyons, including two-needle as well as singleleaf pinyon in other Regions.<br />

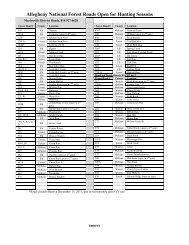

Hosts—The disease causes expanding patches of<br />

mortality in many pinyon stands of the western<br />

slope of the southern and middle Rocky Mountains<br />

as far north as Idaho (figs. 1-2). It has not been<br />

found east of the Continental Divide. Two other<br />

varieties do not occur in this Region: L. wageneri<br />

var. ponderosum infects lodgepole, Jeffrey, and<br />

ponderosa pine; and L. wageneri var. pseudotsugae<br />

infects Douglas-fir. Both those varieties occur<br />

primarily in the northern Rocky Mountains, British<br />

Columbia, and Pacific coast states.<br />

Signs and Symptoms—In advanced disease,<br />

foliage is sparse and sometimes chlorotic (yellow).<br />

A mortality center is often evident, with old snags<br />

near the center, recent mortality farther out, and<br />

symptomatic, live trees at the edge (fig. 1).<br />

Figure 1. Dead and dying pinyon near the edge of a mortality center caused<br />

by black stain root disease. The smaller trees in the foreground may not be<br />

affected yet because their smaller root systems are not yet contacting infected<br />

roots. Photo: Jim Worrall, <strong>USDA</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Service</strong>.<br />

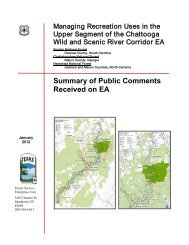

An intense black stain can be found in<br />

wood of the roots, root collar, and often<br />

the lower stem. Unlike the pattern<br />

of blue stain, which progresses radially<br />

along the rays to the inner sapwood,<br />

black stain progresses longitudinally<br />

and somewhat tangentially. Longitudinally,<br />

it forms long streaks following<br />

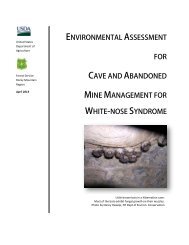

the wood grain (fig. 3). In cross section,<br />

it appears as arcs following short<br />

segments of annual rings (fig. 4).<br />

<strong>Disease</strong> Cycle—Unlike blue-stain<br />

fungi, which colonize rays, this pathogen<br />

colonizes the tracheids (waterconducting<br />

and structural elements) of<br />

the sapwood and causes a wilt disease.<br />

It aggressively invades living wood of<br />

the roots, root collar, and lower stem<br />

until trees are killed. It does not decay<br />

wood.<br />

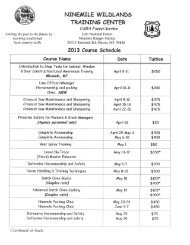

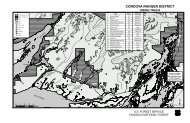

Figure 2. Distribution of black stain root disease in Colorado (from Landis and Helburg 1976)<br />

Where roots grow closely together, the fungus can grow from tree to tree. In this way, mortality centers expand.<br />

Rate of radial expansion of disease centers in pinyon is about 3.3-6.6 ft (1-2 m) per year, but they do not expand<br />

indefinitely. It is not clear why expansion eventually ceases.<br />

<strong>Forest</strong> Health Protection Rocky Mountain Region • 2011

<strong>Black</strong> <strong>Stain</strong> <strong>Root</strong> <strong>Disease</strong> - page 2<br />

Other varieties of the pathogen are transmitted long distances by<br />

insect vectors, primarily root weevils and bark beetles. The vectors<br />

are attracted to dying roots, so the disease is associated with<br />

stand disturbance, especially thinning and road construction. As<br />

the insects burrow into the soil looking for those roots, they tend<br />

to graze on intermingled roots of other trees, thereby inoculating<br />

the pathogen. A vector has not been identified in pinyon, but it is<br />

strongly suspected that there is one and that the relationship to<br />

stand disturbance is similar to that of the disease caused by the<br />

other varieties.<br />

Fruiting of the fungus is almost microscopic and difficult to observe<br />

in the field. Minute black stalks are formed in cavities under<br />

the bark, such as insect galleries. Sticky masses of spores are<br />

produced on the stalks. Insects that contact the fruiting structures<br />

are readily coated with spores.<br />

Impact—In Colorado, disease frequency is clearly associated with<br />

soil depth, precipitation, site quality, and tree size and density.<br />

Stands with large or dense trees may facilitate root-to-root spread<br />

of the pathogen because of more frequent root contacts. However,<br />

rate of disease expansion was not related to density in one study.<br />

Because the pathogen is restricted to pinyon, mixed stands inhibit<br />

tree-to-tree spread of the disease.<br />

In the Rocky Mountains, the disease is most active in southwestern<br />

Colorado, especially in the Four Corners area, but it occurs all<br />

along the Western Slope (fig. 2). Over the long term, black stain is<br />

an important disturbance agent in regulating structure and composition<br />

of pinyon-juniper stands. It creates structural heterogeneity<br />

in the forest, with openings that provide habitat diversity for other<br />

plants and animals. In this sense, the disease promotes old-growth<br />

characteristics of pinyon-juniper stands.<br />

The pathogen dies quickly after host tissue dies and after a stand<br />

replacing fire. <strong>Disease</strong> inci dence then increases with time since<br />

regeneration. Just as fire makes the disease less likely, the disease<br />

makes fire more likely. One of the major impacts of the disease<br />

is an increase in dead fuels. Thus, a fire-disease feedback loop<br />

can be envisioned that contributes to disease reduction and forest<br />

regeneration. The pinyon engraver commonly attacks trees with<br />

black stain. Under endemic beetle populations, black-stain centers<br />

are probably a major source of beetles.<br />

Figure 3. <strong>Black</strong> stain in the lower stem of diseased pinyon.<br />

Stem with the wood exposed in tangential view. Photo: Jim<br />

Worrall, <strong>USDA</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Service</strong>.<br />

Figure 4. <strong>Black</strong> stain in the lower stem of diseased pinyon.<br />

Stem with the wood exposed in transverse view. Photo: Jim<br />

Worrall, <strong>USDA</strong> <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Service</strong>.<br />

Management—No control approach has been effective in pinyon. Cutting and burning killed or symptomatic trees<br />

does nothing to stop the disease, but because pinyon engraver often invades diseased trees before death, sanitation<br />

may be effective in preventing beetle outbreaks. Any replanting should be with species other than pinyon. Trenching<br />

around a disease center to sever all media through which the pathogen may grow has been attempted but<br />

was unsuccessful, probably because the pathogen is often in at least two trees beyond the last symptomatic one.<br />

<strong>Forest</strong> Health Protection Rocky Mountain Region • 2011

<strong>Black</strong> <strong>Stain</strong> <strong>Root</strong> <strong>Disease</strong> - page 3<br />

Another approach is removing all pinyon from in and around disease centers, waiting four years, and replanting<br />

pinyon. This could be effective because the pathogen does not survive long in roots once they are dead. If implemented,<br />

at least three healthy-looking trees beyond the center should be removed.<br />

Any discretionary pinyon cutting would best be done in the fall or winter. Vectors of the other forms of black stain<br />

root disease, which are attracted to fresh cuts, are active in spring and early summer; presumably, the same is true<br />

of the pinyon form.<br />

1. Hessburg, P.F.; Goheen, D.J.; Bega, R.V. 1995. <strong>Black</strong> stain root disease of conifers. <strong>Forest</strong> Insect and <strong>Disease</strong> Leaflet 145<br />

(revised). Washington, DC: U.S. <strong>Department</strong> of Agriculture, <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Service</strong>. 9 p. Online: http://www.fs.fed.us/r6/nr/fid/fidls/<br />

fidl-145.pdf.<br />

2. James, R.L.; Lister, C.K. 1978. Insect and disease conditions of pinyon pine and Utah juniper in Mesa Verde National Park,<br />

Colorado. Biological Evaluation R2-78-4. Lakewood, CO: U.S. <strong>Department</strong> of Agriculture, <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Service</strong>, Rocky Mountain<br />

Region, <strong>Forest</strong> Insect and <strong>Disease</strong> Management.<br />

3. Kearns, H.S.J.; Jacobi, W.R. 2005. Impacts of black stain root disease in recently formed mortality centers in the piñonjuniper<br />

woodlands of southwestern Colorado. Canadian Journal of <strong>Forest</strong> Research 35:461-471.<br />

4. Landis, T.D.; Helburg, L.B. 1976. <strong>Black</strong> stain root disease of pinyon pine in Colorado. Plant <strong>Disease</strong> Reporter 60:713-717.<br />

5. Witcosky, J.J.; Schowalter, T.D.; Hansen, E.M. 1986. Hylastes nigrinus (Coleoptera: Scolytidae), Pissodes fasciatus, and<br />

Steremnius carinatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) as vectors of black stain root disease of Douglas-fir. Environmental<br />

Entomology (15):1090-1095.<br />

<strong>Forest</strong> Health Protection Rocky Mountain Region • 2011