Leonhard Euler, a German princess and topology O18

Leonhard Euler, a German princess and topology O18

Leonhard Euler, a German princess and topology O18

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>O18</strong><br />

<strong>Leonhard</strong> <strong>Euler</strong>, a <strong>German</strong> <strong>princess</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>topology</strong><br />

P. Pieranski<br />

1<br />

Laboratoire de Physique des Solids, Université Paris-Sud, 91405, Orsay, France<br />

“Lisez <strong>Euler</strong>, lisez <strong>Euler</strong>, c’est notre maître à tous »<br />

Pierre-Simon Laplace<br />

The 36 Topical Meeting on Liquid Crystals in Magdeburg gives me a marvellous pretext to<br />

share with you my admiration to <strong>Leonhard</strong> <strong>Euler</strong>, a scientific genius from the Age of Enlightenment.<br />

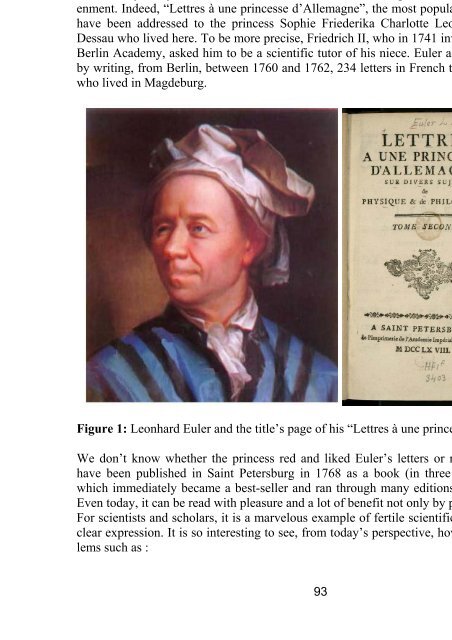

Indeed, “Lettres à une <strong>princess</strong>e d’Allemagne”, the most popular of <strong>Euler</strong>’s writings,<br />

have been addressed to the <strong>princess</strong> Sophie Friederika Charlotte Leopoldine von Anhalt-<br />

Dessau who lived here. To be more precise, Friedrich II, who in 1741 invited <strong>Euler</strong> to join the<br />

Berlin Academy, asked him to be a scientific tutor of his niece. <strong>Euler</strong> accomplished this task<br />

by writing, from Berlin, between 1760 <strong>and</strong> 1762, 234 letters in French to the <strong>princess</strong> Sophie<br />

who lived in Magdeburg.<br />

Figure 1: <strong>Leonhard</strong> <strong>Euler</strong> <strong>and</strong> the title’s page of his “Lettres à une <strong>princess</strong>e d’Allemagne”.<br />

We don’t know whether the <strong>princess</strong> red <strong>and</strong> liked <strong>Euler</strong>’s letters or not. Fortunately, they<br />

have been published in Saint Petersburg in 1768 as a book (in three volumes) (see fig.1)<br />

which immediately became a best-seller <strong>and</strong> ran through many editions [1] <strong>and</strong> translations.<br />

Even today, it can be read with pleasure <strong>and</strong> a lot of benefit not only by <strong>princess</strong>es.<br />

For scientists <strong>and</strong> scholars, it is a marvelous example of fertile scientific thought process <strong>and</strong><br />

clear expression. It is so interesting to see, from today’s perspective, how <strong>Euler</strong> tackled problems<br />

such as :<br />

93

<strong>O18</strong><br />

1. concepts of space, time or reference frame,<br />

2. the nature of sound, its speed or its production by vibrating cords <strong>and</strong> membranes,<br />

3. the nature of light <strong>and</strong> its speed, laws of reflection <strong>and</strong> refraction <strong>and</strong> their use in optical<br />

instruments such as eye, telescopes or microscopes,<br />

4. the Newton’s law of the universal gravitation <strong>and</strong> its application to the motions of planets<br />

<strong>and</strong> comets as well as for explanation of tides<br />

5. laws of the fluid’s flows <strong>and</strong> their application for sailing of ships,<br />

6. the nature of magnetism <strong>and</strong> electricity<br />

7. etc<br />

The lecture of “Lettres ...“ encouraged me to look for other <strong>Euler</strong>’s writings <strong>and</strong> a striking<br />

surprise was waiting for me. Following William Dunham [2], “<strong>Euler</strong> was a veritable Niagara,<br />

one who wrote mathematics faster then most people can absorb it“. Indeed, <strong>Euler</strong>s was<br />

the most prolific mathematician <strong>and</strong> natural scientist of all time. He wrote about 900 papers<br />

<strong>and</strong> books (about 800 pages per year). Publication of his collected works entitled “Opera Omnia“<br />

started in 1911 <strong>and</strong> is still going on. It counts about 80 volumes divided into four series :<br />

Series I Opera mathematica (In 29 volumes; 30 volume-parts)<br />

Series II Opera mechanica et astronomica (In 31 volumes; 32 volume-parts)<br />

Series III Opera physica, Miscellanea (In 12 volumes)<br />

Series IV A. Commercium epistolicum (10 volumes)<br />

Beside “Opera Omnia“ that can be found in some academic libraries, original versions of <strong>Euler</strong>’s<br />

papers are available as pdf files on Web pages of the <strong>Euler</strong> Archive<br />

(http://www.math.dartmouth.edu/~euler/). The index of this archive counts 866 entries.<br />

For the purpose of my talk here in Magdeburg, I looked for <strong>Euler</strong>’s papers dealing with topological<br />

<strong>and</strong> geometrical properties of surfaces that we use today, for example, for description<br />

of bicontinuous lyotropic phases. For instance, the definition of principal curvatures is due to<br />

<strong>Euler</strong> as it shown in Figure 2.<br />

Figure 2 : <strong>Euler</strong>’s expression for the radius of curvature of surfaces. Quotation from “Recherches<br />

sur la courbure des surfaces“ [3].<br />

94

<strong>O18</strong><br />

It is also interesting (<strong>and</strong> touching) to see (but harder to read) the paper, written in Latin, in<br />

which <strong>Euler</strong> writes for the first time his famous formula relating the number of vortices (numerus<br />

angulorum solidorum), the number of edges (numerus acierum) <strong>and</strong> the number of faces<br />

(numerus hedradum) of polyhedra (see Figure 3).<br />

Figure 3: Quotation from the original <strong>Euler</strong>’s paper on topological properties of polyhedra<br />

[4].<br />

In the <strong>Euler</strong>’s work we fin another source of <strong>topology</strong> - the celebrated problem of “Seven<br />

Kônigsberg’s bridges“ (see Figure. 4) - as well as the first definition of this new branch of<br />

mathematics :<br />

“Besides that part of geometry which deals with quantities <strong>and</strong> has always been studiously<br />

cultivated, there is another branch which is still virtually unknown; this was first mentioned<br />

by Leibniz, who called it the “geometry of position” [geometric situs]. It is concerned, he<br />

says, just with the determination of position <strong>and</strong> the investigation of its properties, <strong>and</strong> for<br />

these goals no quantities are to be considered nor any calculations with quantities used.<br />

However it has not yet been clearly defined what problems belong to this geometry of position<br />

<strong>and</strong> what method must be used to solve them. Hence, when a certain problem was recently<br />

mentioned to me which seemed to belong to geometry but did not ask for the determination of<br />

any quantities <strong>and</strong> did not admit a solution by the calculation of quantities either, I did not<br />

doubt that this belongs to the geometry of position – all the more since in its solution only<br />

positions are considered <strong>and</strong> no use is made of calculations. I propose therefore to explain<br />

here the method which I invented for the solution of this kind of problems, as a specimen of<br />

the geometry of position.”<br />

It is also striking to learn that <strong>Euler</strong> who was born in … Switzerl<strong>and</strong>, in Basel, worked almost<br />

all his life in Russia (Saint Petersburg) <strong>and</strong> Prussia (Berlin) <strong>and</strong> wrote almost all of his papers<br />

in Latin <strong>and</strong> in French. Since that time, things changed a little…<br />

How pleasant is to read in the Letter XLI these words: “Maintenant, je me vois en état<br />

d’expliquer à Votre Altesse (La Princesse Sophie) de quelle manière se fait la vision dans les<br />

yeux des hommes et de tous les animaux, ce qui est sans doute la chose la plus merveilleuse à<br />

laquelle l’esprit humain a pu pénétrer.” !<br />

95

<strong>O18</strong><br />

Figure 4 : The original drawing from the <strong>Euler</strong>’s paper on the problem of “Seven Königsberg’s<br />

bridges”. [5].<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

I would to thank François Rothen for illuminating remarks about <strong>Euler</strong>, Bernoulli’s family<br />

<strong>and</strong> the beauty of pure <strong>and</strong> applied mathematics.<br />

References<br />

[1] <strong>Leonhard</strong> <strong>Euler</strong>, “Lettres à une <strong>princess</strong>e d’Allemagne”, Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires<br />

Rom<strong>and</strong>es, Lausanne 2003 (the last edition in French)<br />

[2] William Durham, “The Master of Us All”, The Mathematical Association of America<br />

1999<br />

[3] <strong>Leonhard</strong> <strong>Euler</strong>, “Recherches sur la courbure des surfaces“, originally published in<br />

Memoires de l'academie des sciences de Berlin 16, 1767, pp. 119-143, Opera Omnia:<br />

Series 1, Volume 28, pp. 1 – 22<br />

[4] <strong>Leonhard</strong> <strong>Euler</strong>, “Elementa doctrinae solidorum“, originally published in Novi<br />

Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Petropolitanae 4, 1758, pp. 109-140, Opera<br />

Omnia: Series 1, Volume 26, pp. 71 – 93<br />

[5] <strong>Leonhard</strong> <strong>Euler</strong>, “Solutio problematis ad Geometriam Situs pertinentis“, originally<br />

published in Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Petropolitanae 8, 1741, p 1736,<br />

Opera Omnia: Series 1, Volume 7, p. 1<br />

96