Spagyrical Discovery and Invention - Monoskop

Spagyrical Discovery and Invention - Monoskop

Spagyrical Discovery and Invention - Monoskop

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

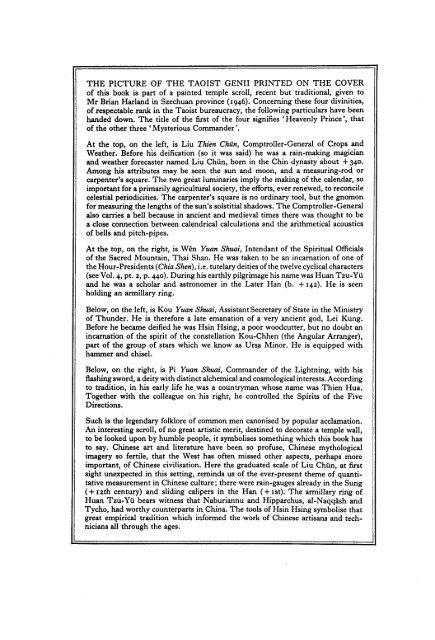

THE PICTURE OF THE TAOIST GENII PRINTED ON THE COVER<br />

of this book is part of a painted temple scroll, recent but traditional, given to<br />

Mr Brian Harl<strong>and</strong> in Szechuan province (1946). Concerning these four divinities,<br />

of respectable rank in the Taoist bureaucracy, the following particulars have been<br />

h<strong>and</strong>ed down. The title of the first of the four signifies 'Heavenly Prince', that<br />

of the other thzee ' Mysterious Comm<strong>and</strong>er'.<br />

At the top, on the left, is Liu Thien ChUn, Comptroller-General of Crops <strong>and</strong><br />

Weather. Before his deification (so it was said) he was a rain-making magician<br />

<strong>and</strong> weather forecaster named Liu Chiin, born in the Chin dynasty about + 340.<br />

Among his attributes may be seen the sun <strong>and</strong> moon, <strong>and</strong> a measuring-rod or<br />

carpenter's square. The two great luminaries imply the making of the calendar, so<br />

important for a primarily agricultural society, the efforts, ever renewed, to reconcile<br />

SCIENCE AND CIVILISATION<br />

IN CHINA<br />

Among the Chinese frequent examples are to be found of<br />

discoveries, especially in the arts, which other nations made<br />

independently whereas the Chinese had come upon them.<br />

long before.<br />

WILLEM TEN RHIJNE<br />

De Arthritide ( + 1683)<br />

And if we look so far as the Sun-rising, <strong>and</strong> hear Paulus<br />

Venetus what he reporteth of the uttermost Angle <strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong><br />

thereof, wee shall finde that those Nations have sent out,<br />

<strong>and</strong> not received, lent knowledge, <strong>and</strong> not borrowed it<br />

from the West. For the farther East (to this day) the more<br />

civill, the farther West the more salvage.<br />

SIR WALTER RALEIGH<br />

'History of the World', + 1614 (+ 1652)<br />

Pt. I, Bk. I, ch~ 7, § 10, sect. 4, p. 98<br />

I take my own intelligence as my teacher.<br />

A-NI-KO, mastert..artisan of Nepal,<br />

addressing the emperor Shih Tsu, + 1263<br />

(Yuan Shih, ch. 203, p. I2a)<br />

I hear, <strong>and</strong> I forget.<br />

I see, <strong>and</strong> I remember.<br />

I do, <strong>and</strong> I underst<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Ten thous<strong>and</strong> words are not worth one seeing.<br />

Chinese proverbs.<br />

I am not yet so lost in lexicography, as to forget that words<br />

are the daughters of earth, <strong>and</strong> that things are the sons of<br />

heaven.<br />

SAMUEL JOHNSON<br />

Preface to his 'Dictionary of the<br />

English Language' ( + 1755)<br />

By studying the organic patterns of heaven <strong>and</strong> earth a fool<br />

can become a sage.<br />

So by watching the times <strong>and</strong> seasons of natural phenomena<br />

we can become true philosophers.<br />

LI CHHUAN<br />

Yin Fu Ching (c. +735)

SCIENCE AND<br />

CIVILISATION IN<br />

CHINA<br />

BY<br />

JOSEPH NEEDHAM, F.R.S., F.B.A.<br />

SOMETIME MASTER OF GONVILLE AND CAIUS COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE<br />

FOREIGN MEMBER OF ACADEMIA SINICA<br />

With the collaboration of<br />

HO PING-YU, PH.D.<br />

PROFESSOR OF CHINESE AT GRIFFITH<br />

UNIVERSITY, BRISBANE<br />

<strong>and</strong><br />

LU GWEI-DJEN, PH.D.<br />

FELLOW OF ROBINSON COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE<br />

<strong>and</strong> a contribution by<br />

NATHAN SIVIN, PH.D.<br />

PROFESSOR OF CHINESE IN THE UNIVERSITY OF<br />

PENNSYLVANIA, PHILADELPHIA<br />

VOLUME 5<br />

CHEMISTRY AND CHEMICAL<br />

TECHNOLOGY<br />

PART IV: SPAGYRICAL DISCOVERY AND<br />

INVENTION: APPARATUS, THEORIES AND GIFTS<br />

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS<br />

CAMBRIDGE<br />

LONDON NEW YORK NEW ROCHELLE<br />

MELBOURNE SYDNEY

Published by the Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge<br />

The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, CB2 IRP<br />

32 East 57th Street, New York, NY 10022, USA<br />

296 Beaconsfield Parade, Middle Park, Melbourne 3206, Australia<br />

© Cambridge University Press 1980<br />

Library of Congress catalogue card number: 54-4723<br />

ISBN: 0<br />

521 08573 x<br />

First published 1980<br />

Printed in Great Britain at the<br />

University Press, Cambridge<br />

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data<br />

Needham, Joseph<br />

Science <strong>and</strong> civilisation in China.<br />

Vol. 5: Chemistry <strong>and</strong> chemical technology.<br />

Part 4: <strong>Spagyrical</strong> discovery <strong>and</strong> invention:<br />

apparatus, theories <strong>and</strong> gifts<br />

I. Science - China - History<br />

2. Technology - China - History<br />

1. Title 11. Wang Ling Ill. Lu Gwei-djen<br />

IV. Ho Ping-yii<br />

509'.5 1 Q127·c5 54-4723<br />

ISBN 0 521 08573 x

To<br />

WU HSOEH-CHOU<br />

sometime Director of the Chemical Institute of<br />

Academia Sinica<br />

<strong>and</strong><br />

CHANG TZU-KUNG<br />

sometime Chemical Adviser to the National Resources<br />

Commission<br />

in warmest recollection of long<br />

<strong>and</strong> enlightening discussions at<br />

Kunming <strong>and</strong> Nan-wen-chhiian<br />

1942 to 1946<br />

as also in memory of an earlier friend<br />

LOUIS RAPKINE<br />

-<br />

sometime Professor of Biochemistry at the Institut de<br />

Biologie Physico-Chimique, Paris<br />

in our youth<br />

colleague at the Marine Station at Roscoff<br />

compass-needle for truth <strong>and</strong> social justice<br />

Spinoza redivivus<br />

this volume is dedicated

CONTENTS<br />

List of Illustratz"ons<br />

List of Tables<br />

List of Abbrevz'atz"ons .<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Author's Note .<br />

. page xiii<br />

XXlll<br />

xxv<br />

XXIX<br />

xxxi<br />

33 ALCHEMY AND CHEMISTRY (contz"nued)<br />

page 1<br />

(f) Laboratory apparatus <strong>and</strong> equipment, p. 1<br />

(I) The laboratory bench, p. 10<br />

(2) The stoves lu <strong>and</strong> tsao, p. I I<br />

(3) The reaction-vessels tz"ng (tripod, container, cauldron) <strong>and</strong> kuei (box,<br />

casing, container, aludeI), p. 16<br />

(4) The sealed reaction-vessels shen shih (aludel, lit. magical reactionchamber)<br />

<strong>and</strong> yao fu (chemical pyx), p. 22<br />

(5) Steaming apparatus, water-baths, cooling jackets, condenser tubes <strong>and</strong><br />

temperature stabilisers, p. 26<br />

(6) Sublimation apparatus, p. 44-<br />

(7) Distillation <strong>and</strong> extraction apparatus, p. 55<br />

(i) Destillatio per descensum, p. 55<br />

(ii) The distillation of sea-water, p. 60<br />

(iii) East Asian types of still, p. 6z<br />

(iv) The stills of the Chinese alchemists, p. 68<br />

(v) The evolution of the still, p. 80<br />

(vi) The geographical distribution of still types, p. 103<br />

(8) The coming of Ardent Water, p. 121<br />

(i) The Salernitan quintessence, p. 12Z<br />

(ii) Ming naturalists, p. 13z<br />

(iii) Thang' burnt-wine', p. 141<br />

(iv) Liang 'frozen-out wine', p. 151<br />

(v) From icy mountain to torrid still, p. 155<br />

(vi) Oils in stills; the rose <strong>and</strong> the flame-thrower, p. 158<br />

(9) Laboratory instruments <strong>and</strong> accessory equipment, p. 16z

x<br />

CONTENTS<br />

(g) Reactions in aqueous medium, p. 167<br />

(1) The formation <strong>and</strong> use of a mineral acid, p. I72<br />

(2) 'Nitre' <strong>and</strong> hsiao; the recognition <strong>and</strong> separation of soluble salts, p. 179<br />

(3) Saltpetre <strong>and</strong> copperas as limiting factors in East <strong>and</strong> West, p. 195<br />

(4) The precipitation of metallic copper from its salts by iron, p. 201<br />

(5) The role of bacterial enzyme actions, p. 204<br />

(6) Geodes <strong>and</strong> fertility potions, p. 205<br />

(7) Stabilised lacquer latex <strong>and</strong> perpetual youth, p. 207<br />

(h) The theoretical background of elixir alchemy [with Nathan Sivin], p. 210<br />

(1) Introduction, p. 210<br />

(i) Areas of uncertainty, p. 21 I<br />

(ii) Alchemical ideas <strong>and</strong> Taoist revelations, p. 212<br />

(2) The spectrum of alchemy, p. 220<br />

(3) The role of time, p. 221<br />

(i) The organic development of minerals <strong>and</strong> metals, p. 223<br />

(ii) Planetary correspondences, the First Law of Chinese physics, <strong>and</strong><br />

inductive causation, p. 225<br />

(iii) Time as the essential parameter of mineral growth, p. 231<br />

(iv) The subterranean evolution of the natural elixir, p. 236<br />

(4) The alchemist as accelerator of cosmic process, p. 242<br />

(i) Emphasis on process in theoretical alchemy, p. 248<br />

(ii) Prototypal two-element processes, p. 251<br />

(iii) Correspondences in duration, p. 264-<br />

(iv) Fire phasing, p. 266<br />

(5) Cosmic correspondences embodied in apparatus, p. 271<br />

(i) Arrangements for microcosmic circulation, p. 281<br />

(ii) Spatially oriented systems, p. 286<br />

(iii) Chaos <strong>and</strong> the egg, p. 292<br />

(6) Proto-chemical anticipations, p. 298<br />

(i) Numerology <strong>and</strong> gravimetry, p. 300<br />

(ii) Theories of categories, p. 305<br />

(i) Comparative macrobiotics, p. 323<br />

(1) China <strong>and</strong> the Hellenistic world, p. 324<br />

(i) ParaIlelisms of dating, p. 324-<br />

(ii) The first occurrence of the term 'chemistry', p. 339

CONTENTS<br />

Xl<br />

(iii) The origins of the root' chem-', p. 346<br />

(iv) Parallelisms of content, p. 355<br />

(v) Parallelisms of symbol, p. 374<br />

(2) China <strong>and</strong> the Arabic world, p. 388<br />

(i) Arabic alchemy in rise <strong>and</strong> decline, p. 309<br />

(ii) The meeting of the streams, p. 408<br />

(iii) Material influences, p. 429<br />

(iv) Theoretical influences, p. 453<br />

(v) The name <strong>and</strong> concept of 'elixir', p. 472<br />

(J) Macrobiotics in the Western world, p. 491<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHIES .<br />

5 10<br />

Abbreviations, p. 5 I I<br />

A. Chinese <strong>and</strong> Japanese books before + 1800, p. 519<br />

Concordance for Tao Tsang books <strong>and</strong> tractates, P:571<br />

B. Chinese <strong>and</strong> Japanese books <strong>and</strong> journal articles since + 1800, p. 574<br />

C. Books <strong>and</strong> journal articles in Western languages, p. 596<br />

GENERAL INDEX .<br />

Table of Chinese Dynasties.<br />

Summary of the Contents of Volume 5<br />

Romanisation Conversion Table

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS<br />

1374 Stove platform from Kan Chhi Shih-liu Chuan Chin Tan (Sung).<br />

1375 Stove platforms from Tan Fang Hsu Chih ( + 1163)<br />

1376 Stove platform from Yun Chi Chhi Chhien (+ 1022)<br />

1377 The 'inverted-moon stove' from Chin Tan Ta Yao Thu (+ 1333)<br />

. 1378 Stove depicted in Yun Chi Chhi Chhien (+ 1022) .<br />

page 10<br />

page II<br />

page II<br />

page 13<br />

page 13<br />

1379 Stoves drawn in Thai-ChiChen-Jen Tsa Tan Yao Fang (a text probably<br />

of the Sung) . page 13<br />

1380a, b Pottery stove designed to heat four containers at one time, in an<br />

excavated tomb of the Thang period, c. + 760 page 14<br />

1380c A bronze 'hot-plate' of the - 11th century, for warming sacrificial<br />

wine in liturgical vessels . page 15<br />

Reproduced by permission of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York<br />

1381 Gold reaction-vessel, a drawing from Yun Chi Chhi Chhien (+ 1022) page 17<br />

1382 Covered reaction-vessel, a drawing from the same work page 17<br />

1383 ' Suspended-womb' reaction-vessel, also with three legs, from Chin<br />

Tan Ta Yao Thu (+ 1333) page 17<br />

1384 Aludel from the Kan Chhi Shih-liu Chuan Chin Tan (Sung) page 18<br />

1385 Furnace <strong>and</strong> reaction-vessel, from Chhien Hung Chia Keng . .. (+ 808<br />

or later) . page 18<br />

1386 Types of aludels <strong>and</strong> reaction-vessels from Thai-Chi Chen-Jen ...<br />

(probably Sung) page 19<br />

1387 Reaction-chamber from the King Tao Chi ( + 1144 or later) page 19<br />

1388 'Precious vase' probably of Thang date page 20<br />

Reproduced by permission of the Provincial Historical Museum, Thaiyuan, Shansi<br />

1389 Bronze reaction-vessel (ting) with clamp h<strong>and</strong>le mechanism to permit<br />

tight sealing. From the tomb of Liu Sheng (d. - 113) at Manchheng<br />

• : page 2 I<br />

1390 Reaction-chamber from the Chin Hua Chhung Pi Tan Ching Pi Chih<br />

( + 1225) . page 22<br />

1391 Reconstruction of the yao1u 'bomb' from the Thai-Chhing Shih Pi Chi<br />

(Liang, + 6th century, or earlier) . page 22 _<br />

1392 A bronze tui, possibly used as a reaction-vessel, Chou period, c. - 6th<br />

century, from Chia-ko-chuang, near Thangshan in Hopei page 23

XIV<br />

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS<br />

1393 Bronze tui, usable as a reaction-vessel, Chou period, between - 493<br />

<strong>and</strong> - #7, from the tomb of a Marquis of Tshai, near Shou-hsien<br />

in Anhui. page 24<br />

1394 Stoppered aludel of silver, from the hoard of the son of Li Shou-Li,<br />

buried at Sian in + 756 . page 25<br />

1395 Neolithic pottery vessels connected with the origins of chemical<br />

apparatus, all from the - 3rd millennium page 26<br />

1396 Three-lobed spouted jug (ii) of red pottery, from a neolithic site at<br />

Shih-chia-ho in Thien-men Hsien, Hupei, c. - 2000 page 26<br />

1397 A li vessel of grey pottery, in the style of the Hsiao-thun culture,<br />

excavated from neolithic levels at Erh-li-kang, near Chengchow in<br />

Honan, dating from the - 23rd to the - 20th century page 27<br />

1398 Tripod vessel (ting) of coarse dark grey pottery, from a neolithic site at<br />

Shih-chia-ho in Thien-men Hsien, Hupei page 28<br />

1399 Bronze hsien of the Shang period, c. - 1300 page 28<br />

1400 Early Chou bronze hsien, c. - 1I00, photographed to show the grating<br />

page 29<br />

Reproduced by permission of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto<br />

1401 Bronze tseng, i.e. an apparatus of two separate vessels with a grating<br />

between them, <strong>and</strong> fitting well together. From a tomb of the - 4th or<br />

- 3rd century at Chao-ku near Hui-hsien in Honan pale 29<br />

1402 Bronze ting with well moulded water-seal rim, c. - 500, from Huanghsien<br />

page 30<br />

1403 Characteristic pickling pot in common use in China, usually in red<br />

pottery, with annular water-seal for maintaining almost anaerobic<br />

conditions page 30<br />

1404 Tomb-model of stove <strong>and</strong> steamer from Chhangsha; Earlier Han<br />

period, - 2nd or - 1st century page 31<br />

1405 Tomb-model of stove, <strong>and</strong> chimney with roof, from a Later Han<br />

grave at Chhangchow<br />

page 3 I<br />

1406 Elaborately ornamented water-bath, with grate underneath, in bronze,<br />

of middle or late Chou date (c. - 6th century) page 32<br />

Reproduced by permission from the Sumitomo Collection, Kyoto<br />

1407 Diagram of furnace with condenser, from the Huan Tan Chou Hou<br />

Chueh, a Thang text of the + 9th century page 34-<br />

1408 Stove <strong>and</strong> steamer-support, from Chin Hua Chhung Pi Tan Ching . .. ,<br />

a Sung text, + 1225 page 34

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS<br />

-1409 Water-cooled reaction-vessel from the Chin Hua Chhung Pi Tan<br />

Ching . .., + 1225. The upper reservoir is prolonged into a blind<br />

finger below, so that the cold water can moderate the temperature<br />

of the reaction proceeding in the chamber page 36<br />

1410 Water-cooled reaction-vessel, from the same work (+ 1225). The<br />

central tube descending from the cooling reservoir is enlarged into<br />

a single bulb . page 37<br />

1411 Water-cooled reaction-vessel, from the same work (+ 1225). The<br />

central tube has two bulbs flattened like radiator fins page 38<br />

1412 Water-cooled reaction-vessel, from the same work (+ 1225). The central<br />

tube_ connects the cooling reservoir with a peripheral water-jacket in<br />

the wall of the reaction chamber. page 38<br />

1413 Water-cooled reaction-vessel, from the same work (+ 1225). Here the<br />

peripheral water-jacket is provided with a filling tube at one side aswell<br />

as the connection with the cooling reservoir through the central<br />

tube page 39<br />

1414 Water-cooled reaction-vessel, from the same work (+ 1225). There is no<br />

central tube, <strong>and</strong> the cooling reservoir connects directly with the<br />

peripheral water-jacket at one point on its circumference above. page 40<br />

1415 Water-cooled reaction-vessel, from the same work (+ 1225). Cooling<br />

reservoir,- central tube, <strong>and</strong> two water-jackets in the form of hoods,<br />

but no peripheral cold-water walls . page 41<br />

1416 Water-cooled reaction-vessel, from the same work (+ 1225). Cooling<br />

reservoir with complete water-jacket horseshoe-shaped in crosssection<br />

but continuing under the floor of the chamber page 42<br />

1417 Water-cooled reaction-vessel, from the same work (+ 1225). Cooling<br />

reservoir prolonged below into three meridional tubes passing<br />

around the chamber <strong>and</strong> meeting at the bottom page 42<br />

1418 A sublimatory vessel in the shape of a narrow-mouthed ting, from the<br />

Hsiu Lien Ta Tan Yao Chih (Sung) page 45<br />

1419 Traditional Thaiwanese sublimatories for camphor page 45<br />

1420 Camphor sublimation with steam as carried out in Japan, from the<br />

Nihon Sankai Meibutsu Zue ( + 1754) page 46<br />

1421 Camphor still of Japanese type as used in Thaiwan (Davidson) .<br />

1422 Traditional sublimation-distillation apparatus for camphor used m<br />

South China . page 48<br />

1423 Diagram to illustrate the operation of this apparatus<br />

1424 Bronze' rainbow teng' of Later Han date ( + 1st or + 2nd century)<br />

xv<br />

page 48<br />

page 50

XVI<br />

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS<br />

1425 Cross-section of another example of this apparatus, found at Chhangsha<br />

<strong>and</strong> dating from the Early Han period, c. - 1st century . page 50<br />

1426 Figurine of an amphisbaena of two-headed serpent, probably personifying<br />

the rainbow <strong>and</strong> representing a visible rain-bringing dragon,<br />

generally beneficent page 52<br />

Reproduced by permission of Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto<br />

1427 Rainbow teng with only one side-tube, Sung in date, but the bronze<br />

inlaid in Chhin or Han style . page 52<br />

Reproduced by permission of the British Museum<br />

1428 Modern still for the purification of mercury in high vacuum, lined<br />

with glass <strong>and</strong> porcelain to prevent contact with the metal page 53<br />

1429 Single-tube rainbow teng in the form of a serving-maid holding a<br />

lamp, from the tomb of Liu Sheng, Prince Ching of Chung-shan,<br />

d. - II3 ' page 54<br />

1430 Bamboo tube for descensory distillation of mercury, from Ta- Tung<br />

Lien Chen Pao Ching . .. (Thang) . page 56<br />

1431 Stove arranged for descensory distillation; drawings from the Kan<br />

Chhi Shih-liu Chuan Chin Tan, a Sung work . page 56<br />

1432 Furnace arranged for descensory distillation, ,from the Chhien Hung<br />

Chia Keng ... of + 808 (Thang). . '-', . . . . page 58<br />

1433 'Pomegranate' flask (an ambix) used in descensory distillation, from<br />

Chin Hua Chhung Pi Tan Ching Pi Chih of + 1225 (Sung) page 58<br />

1434 Mercury distillation per descensum depicted in the Cheng Lei Pen Tshao<br />

of + 1249 (Sung) page 59<br />

1435 Condensing the distillate from sea-water in a suspended fleece, an<br />

ancient method illustrated by Conrad Gesner 10 his Thesaurus<br />

Euonymus Philiatri (+ 1555) . page 61<br />

1436 The' Mongolian' still (Hommel) page 62<br />

1437 The' Chinese' still (Hommel) page 63<br />

1438 Alcohol still at Tung-cheng in Anhui (Hommel), showing the external<br />

appearance of a traditional Chinese distillation apparatus page 64<br />

1439 Pewter cooling reservoir or condenser vessel of a traditional liquor still,<br />

photographed upside down, at Lin-chiang in Chiangsi (Hommd) page 64<br />

1440 Pev.1:er catch-bowl <strong>and</strong> side-tube of a traditional liquor still, photographed<br />

upside down, at Lin-chiang in Chiangsi (Hommel) page 65<br />

. 1441 Traditional Chinese liquor still at Chia-chia-chuang Commune, Shansi<br />

page 65<br />

1442 Traditional still from the Nung Hsiieh Tsuan Yao (1901) by Fu Tseng-<br />

Hsiang . page 66

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS<br />

XVll<br />

1443 A wine-distilling scene from the frescoes at the cave-temples ofWan-fohsia<br />

(Yii-lin-khu) in' Kansu, dating from the Hsi-Hsia period<br />

( + 1032 to + 1227) . page 66<br />

1444 A late + 18th-century coloured MS. drawing of a Chinese wine still page 67<br />

Reproduced by permission of the Victoria <strong>and</strong> Albert Museum<br />

1445 Traditional-style drawing of a Chinese liquor distillery<br />

1446 East Asian stills from the Tan Fang Hsu Chih of + 1163 (Sung) .<br />

page 68<br />

page 69<br />

1447 Another Chinese apparatus from Chih-Chhuan Chen-Jen Chiao<br />

Ching Shu, ascribed to the Chin period ( + 3rd or + 4th century), but<br />

more probably Thang ( + 8th or + 9th) . page 72<br />

1448 East Asian stills from Chin Hua Chhung Pi Tan Ching Pi Chih of<br />

+ 1225 (Sung) page 73<br />

1449 One of the forms of the herotakis (reflux distillation) apparatus of the<br />

Greek proto-chemists page 74<br />

1450 Sherwood Taylor's conjectural reconstruction of the long type of<br />

herotakis apparatus . page 75<br />

1451 A drawing from the Liber Florum Geberti, a pre-Geberian Arabic-<br />

Byzantine MS. in Latin, probably of the + 13th century. page 77<br />

1452 Mercury still from the Tan Fang Hsu Chih of + 1163 (Sung) page 77<br />

1453 A retort still for mercury, from Thien Kung Khai Wu ( + 1637) by Sung<br />

Ying-Hsing page 78<br />

1454 Chart to illustrate the evolution of the still . page 81<br />

1455 Distillation <strong>and</strong> extraction apparatus from pre-Akkadian times in<br />

Northern Mesopotamia, c. - 4th <strong>and</strong> - 3rd millennia (Levey). page 82<br />

1456 Aludel with annular shelf used by the Arabic alchemists as a sublimatory<br />

or 'still', from a text of al-Kati (+ 1034). page 83<br />

1457 Aludels with annular shelves or gutters, from a late + 13th-century<br />

MS. of Geber, Summa Perfectionis Magisterii . page 83<br />

1458 Illustration of Hellenistic apparatus from MS. Paris 2327, a copy made<br />

in + 1478 of the proto-chemical Corpus in Greek compiled by<br />

Michael Psellus in the + 11th century, <strong>and</strong> containing material from<br />

the ± 1st century onwards page 84<br />

1459 Page from a + 14th-century MS. of the Turba <strong>and</strong> of Geberian<br />

writings . page 85<br />

Reproduced by permission of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge<br />

1460 Distillation equipment fround at Taxila in the Punjab, India, <strong>and</strong><br />

dating from the ± 1st century. page 87

XVlll<br />

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS<br />

1461 Hellenistic still with no guttered still-head but a single side-tube of<br />

large diameter leading to a receiver-the first of all Western 'retorts'<br />

page 88<br />

1462 Drawing of a retort in a Syriac MS. copied in the + 16th century but<br />

containing material going back to the + 1St century, <strong>and</strong> much from<br />

the + 2nd to the + 6th . page 88<br />

1463 A dibikos or Hellenistic still with two side-tubes<br />

1464 The same as reconstructed by Sherwood Taylor.<br />

1465 The earliest representation of a Moor's head cooling bath, a drawing by<br />

Leonardo da Vinci, c. + 1485 . page 90<br />

1466 The Moor's head condenser as depicted by Conrad Gesner (De<br />

Remediis Secretis, + 1569) page 90<br />

1467 The elegant picture of the Moor's head in Mattioli's De Ratione<br />

Distill<strong>and</strong>i, + 1570 .<br />

page 9 I<br />

1468 Bladder still-head cooler, from Gesner's De Remediis Secretis, + 15~ page 92<br />

1469 Reconstruction by Ladislao Reti of the dephlegmator described by<br />

Taddeo Alderotti in his Consilia MedicinaJia (late + 13th century) page 92<br />

1470 The oldest representation of a water-cooling condenser surrounding<br />

the side-tube between the still <strong>and</strong> the receiver, in a MS. of + 1420<br />

by J ohannes Wenod de Veteri Castro page 94<br />

1471 A form of Moor's head described by Hieronymus Brunschwyk soon<br />

after + 1500 in Liber de Arte Distill<strong>and</strong>i de Compositis (1st ed.,<br />

+ 15 12) . page 94<br />

1472 An early drawing of a dephlegmator arranged for fractionation, from<br />

a Bavarian MS. dated + 1519 . page 95<br />

Reproduced by pennission of the Jagellonian Library, Cracow<br />

1473 a A complex dephlegmator of five vessels depicted by Conrad Gesner in<br />

+ 1552, from De Remediis Secretis (+ 1569) page 96<br />

1473 b Dephlegmator from the Kriiuterbuch of Adam Lonicerus (+ 1578) page 96<br />

1473c Conjectural design of the most ancient Mongolian-Chinese still type page 96<br />

1474 Coiled serpentine side-tube descending through a reservoir of cold<br />

water, from Gesner's De Remediis Secretis (+ 1569). page 99<br />

1475 Solar still for purifying water page 99<br />

1476 Apparatus for the continuous extraction of plant or other material at the<br />

boiling temperature of the solvent . page 100<br />

1477 The Mongolian <strong>and</strong> Chinese stills in modern chemical practice. page 101<br />

1478 Mongolian <strong>and</strong> Chinese principles in molecular stills. page r02<br />

1479 The Mongol still in folk use; the can of the Crimean Cossacks for<br />

distilling arak from kumiss page 104

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS<br />

XIX<br />

1480 Forms of still in use among Siberian peoples for arak. page 105<br />

1481 A combination of Chinese <strong>and</strong> Western designs: the extraction<br />

apparatus for materia medica used among the Algerians . page 106<br />

1482 A Tarasco still from the Lake Patzcuaro region in Mexico . page 106<br />

1483 Zapotec still, also from Mexico, one of a series set along a bench-like<br />

stove page 107<br />

1484 Part of a Chinese still used by the Cora <strong>and</strong> Tarasco Indians in Mexico<br />

page 108<br />

1485a A Mongol still used by the Huichol Indians in Mexico page 109<br />

1485 b 'Trifid' pottery vessel from the Colima culture of north-western<br />

Mexico, c. - 1450 . page 109<br />

1486 Western-type still with cooling-barrel condenser on the side-tube used<br />

for the distillation of arak by the Wotjaks in Siberia page 112<br />

1487 a Reconstruction of the' pot <strong>and</strong> gun-barrel' still described in the Chil<br />

Chia Pi Yung Shih Lei Chhilan Chi of + 1301. page 113<br />

1487 b Still of Hellenistic type used in China for the industrial preparation of<br />

essential oil of cassia, from the leaves <strong>and</strong> flowers of Cinnamomum<br />

Cassia page I 13<br />

1488a Japanese rangaku or + 18th-century pharmaceutical extractor still page 114<br />

1488b Cross-section of the same. page 114<br />

1489 Chinese industrial still of Western type for the distillation of kao-liang<br />

wme page 115<br />

1490 Cross-section of a chhi kuo for cooking foods in water just condensed<br />

from steam, without loss of volatile flavouring subst~hces page I 16<br />

1491 Japanese industrial still for peppermint oil. page 116<br />

1492 Triple still for peppermint oil, also from a Japanese source. page 117<br />

1493 Vietnamese industrial still for the essential oils of star anise, Illicium<br />

verum page I 18<br />

1494a Vietnamese alcohol still .<br />

page 119<br />

1494b Another Vietnamese alcohol still<br />

page 119<br />

1495 Chinese industrial still for star anise oil (pai chio yu) page I 19<br />

1496 ' Rosenhut' still for alcohol distillation, from Puff von Schrick's book,<br />

first published in + 1478. page 125<br />

1497 The mastarion or 'cold-still' of Zosimus page 126<br />

1498<br />

1499<br />

Glass still-head of mastarion type from Egypt, datable from the + 5th<br />

to the + 8th century page 126<br />

Reproduced by permission of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto<br />

Drawings of stills in al-Kindi's Kitiib Kimiyii' al-'Itr wa'I-Taf'idiit<br />

(Book of Perfume Chemistry <strong>and</strong> Distillations) page 127

xx<br />

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS<br />

1500 A' Moor's head' still from a Moorish l<strong>and</strong>, cross-section of the Algerian<br />

steam distillation apparatus described by Hilton-Simpson page 130<br />

1501 Steam distillation apparatus of compact form in tinned copper from<br />

Fez in Morocco page 130<br />

1502 Wen Ti, ruler of the State of Wei in the Three Kingdoms period,<br />

pictured with his colleagues of the States of Shu <strong>and</strong> Wu in a MS. of<br />

+ 1314, the Jiimi'al-Taw~rikh (Collection of Histories) by Rashid<br />

ai-Din al-Hamdani, the Chinese portion of which was completed in<br />

+ 130 4 . page I38<br />

Reproduced by permission of the Royal Asiatic Society, London<br />

1503 Modern alcohol vat still for fen chiu at Hsing-hua Tshun, Shansi page ISO<br />

1504 Modern vat stills at Shao-hsing, Chekiang . page 150<br />

1505 Pestle <strong>and</strong> mortar, from the Tan Fang Hsii Chih of + 1163. page 163<br />

1506 Cast-iron pestle <strong>and</strong> mortar, Later Han in date, from a tomb at Yang-tzu<br />

Shan near Chhcngtu excavated in 1957 .<br />

page I63<br />

1507 Bronze pestle <strong>and</strong> mortar, Hsin or Later Han in date, found during the<br />

construction of the Chhengtu-Kunming Railway page 164<br />

1508 Collapsible ladle in silver, part of the hoard of the son of Li Shou-Li,<br />

probably buried in + 756, at Sian . page 164<br />

1509 Origins of the gas bubbler or Woulfe bottle; typical Chinese tobacco<br />

water-pipes page 165<br />

1510 Double-mouthed kundika pot or bottle, of buff clay with ying-chhing<br />

(shadow blue) glaze; Indian in form but Thang in date . page 166<br />

Reproduced by permission of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto<br />

1511 The saltpetre ( nitre) industry at Ho-chien-fu, showing the removal of<br />

the percolated earth, with old percolating jars in the foreground page 193<br />

1512 A saltpetre works in Japan, from the Nihon no Sangyo Gijutsu (Industrial<br />

Arts <strong>and</strong> Technology in Old Japan) by Oya Shin'ichi page 193<br />

1513 A Japanese ferrous sulphate works, from the Nihon Sankai Meibutsu Zue<br />

(Illustrations of Processes <strong>and</strong> Manufactures), + 1754 page 200<br />

1514 A geode (yii yii liang) from ferrugineous clay; a page of the Ching Lei<br />

Pen Tshao (Reorganised Pharmacopoeia) of + 1249. page 206<br />

1515 The Five Elements <strong>and</strong> the Yin <strong>and</strong> Yang as phases of a cyclical process<br />

page 226<br />

1516 Diagram to illustrate the conception of' time-controlling substances'<br />

page 244<br />

1517 Fire-distances prescribed in the Thai- Wet' Ling Shu Tzu- Wen Lang-Kan<br />

Hua Tan Shen Chen Shang Ching (Divinely Written Exalted Spiritual<br />

Realisation Manual in Purple Script on the Lang-Kan (Gem) Radiant<br />

Elixir; a Thai-W ei Scripture), a text of the late + 4th century page 269

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS<br />

XXI<br />

1518 Chhen Shao-Wei's linear fire-phasing system, from his Chhi Fan Ling<br />

Sha Lun (On Numinous Cinnabar Seven Times Cyclically Transformed),<br />

c. + 713 . page 272<br />

1519a Meng Hsii's two-variable phasing system, from Chin Hua Chhung Pi<br />

Tan Ching Pi Chih ( + 1225) . page 276<br />

1519b Two of the Twelve Hour-Presidents (Spirits of the Double-hours).<br />

A pair of Han tiles . page 280<br />

Reproduced by permission of the Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh<br />

1520 A page from Chao Nai-An's Chhien Hung Chia King Chih Pao Chi<br />

Chhing (Complete Compendium on the Perfected Treasure of Lead,<br />

Mercury, Wood <strong>and</strong> Metal). Perhaps Thang ( + 808) in date, but more<br />

probably Wu Tai or Sung page 283<br />

1521 Tshao Yuan-Yii's reconstruction of a mediaeval Taoist alchemical<br />

laboratory in a cave page 290<br />

1522 Drawings of native cinnabar from the Ching Lei Pen Tshao of + 1249<br />

page 300<br />

1523 Chhen Shao-Wei's mercury yields from different varieties of cinnabar<br />

page 304<br />

1524 A representation of the' gold-digging ants' of Asia, from the + 1481<br />

Augsburg edition of M<strong>and</strong>eville's 'Travels' page 338<br />

1525 Hellenistic Ouroboros. A representation from MS. Marcianus 299,<br />

fo1. 188v. page 375<br />

1526 Hellenistic Ouroboros. Another representation, from Paris MS. 2327,<br />

fo1. 196 (in Olympiodorus, late + 5th century) page 375<br />

1527 Hellenistic Ouroboros on a Gnostic gem, one of the many Abraxas<br />

talismans. Date ± 1st century, contemporary with ps-Cleopatra. page 375<br />

1528 Examples ofthe Chinese Ouroboros . pages 382-3<br />

(a) Reproduced by permission of the British Museum<br />

(b) Reproduced by permission of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities,<br />

Stockholm<br />

(c) Reproduced by permission of the Musee Guimet, Paris<br />

(d) Reproduced by permission from the collection of Mrs Brenda Seligman<br />

(e) Reproduced by permission from the Eumorphopoulos Collection in the<br />

British Museum<br />

1529 A painting by Tung Chhi-Chhang ( + 1555 to + 1636), one of the first<br />

Chinese painters to try the European style. St Thomas of the lndies,<br />

who in the apocryphal Acts of Thomas had an encounter with an<br />

Ouroboros page 383<br />

1530 A Chinese Turba Philosophorum, from Shen Hsien Thung Chien. page 400<br />

1531 a Map to show the communication routes, mainly overl<strong>and</strong>, between the<br />

Chinese <strong>and</strong> Arabic culture-areas, as also the relation between<br />

Chinese, Iranian <strong>and</strong> Eastern Mediterranean l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> cities . pages 406-7

XXll<br />

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS<br />

1531 b Statuette of a Persian or Arabic merchant, Thang in date.<br />

Reproduced by pennission of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto<br />

1532 Evidence of the close relations between China <strong>and</strong> the Islamic countries<br />

in the Sung; a silver ewer of West Asian character. page 422<br />

1533 Yin <strong>and</strong> Yang (the Moon <strong>and</strong> the Sun) as controllers of the Six Metals,<br />

an illustration from an Arabic MS. of AM al-Qasim al-' Iraqi, c.<br />

+ 1280 • page 458<br />

Reproduced by permission of the British Museum<br />

1534 Chart of the 'Ilm al-Mizan (Science of the Balance) of the Jibirian<br />

Corpus . page 460<br />

1535 The tours of the god Thai I through the spaces of the universe represented<br />

by the nine cells of the magic square of three; from the Thang<br />

<strong>and</strong> Sung liturgical encyclopaedia Tao Fa Hui Yuan page 466<br />

1536 Directions for a Taoist ritual dance symbolising the circling of the<br />

Great Bear (pei tou) in the heavens; from the Thai-Shang Chu Kuo<br />

Chiu Min Tsung Chen Pi Yao (+ I I 16) . page 467<br />

1537 Esoteric objects still extant from the collections of Rudolf n in Prague<br />

page 489<br />

1538 Chart to illustrate the multi-focal origins of proto-chemistry page 504

LIST OF TABLES<br />

114 Names <strong>and</strong> details of Tao Tsang texts useful in the study of chemical<br />

apparatus . pages 2-3<br />

115 Technical terms of operations pages 4-'7<br />

116 Order of operations in the elixir preparation of the Chin /fua Chhung Pi<br />

Tan Ching Pi Chih, ch. 2 (TT907) . page 43<br />

117 General scheme of the passages in the Huai Nan Tzu book about the<br />

growth <strong>and</strong> development of minerals <strong>and</strong> metals in the earth page 225<br />

118 Chhen Shao-Wei's helical fire-phasing system page 273<br />

119 Yan Tsai's helical fire-phasing system . page 274<br />

Symbolic correlations of the Five Minerals page 287<br />

Symbolic correspondences of four metals <strong>and</strong> minerals page 290<br />

120 Chemical categories from the Wu Hsiang Lei Pi Yao page 320<br />

Symbolic correlations among the $llbians page 428<br />

Life-expectancy at birth in Europe, + 1300 to 1950 page 508

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS<br />

The following abbreviations are used in the text <strong>and</strong> footnotes. For abbreviations used<br />

for journals <strong>and</strong> similar publications in the bibliographies, see pp. 5 I I ff.<br />

B<br />

CC<br />

CCIF<br />

CCYF<br />

CHS<br />

CJC<br />

CLPT<br />

CSHK<br />

CTPS<br />

EB<br />

HCCC<br />

HCSS<br />

HFT<br />

HHPT<br />

HHS<br />

HNT<br />

ICK<br />

Bretschneider, E. (1), Botanicon Sinicum.<br />

Chia Tsu-Chang & Chia Tsu-Shan (1), Chung-Kuo Chih Wu Thu<br />

Chien (Illustrated Dictionary of Chinese Flora), 1958.<br />

Sun Ssu-Mo, Chhien Chin I Fang (Supplement to the Thous<strong>and</strong><br />

Golden Remedies), between + 660 <strong>and</strong> + 680.<br />

Sun Ssu-Mo, Chhien Chin Yao Fang (Thous<strong>and</strong> Golden Remedies),<br />

between +650 <strong>and</strong> +659.<br />

Pan Ku (<strong>and</strong> Pan Chao), Chhien Han Shu (History of the Former<br />

Han Dynasty), c. + 100.<br />

Juan Yuan, Chhou Jen Chuan (Biographies of Mathematicians <strong>and</strong><br />

Astronomers), + 1799. With continuations by Lo Shih-Lin, Chu<br />

Kho-Pao <strong>and</strong> Huang Chung-Chiin. In HCCC, chs. 159ff.<br />

Thang Shen-Wei et al. (ed.), CMng Lei Pen Tshao (Reorganised<br />

Pharmacopoeia), ed. of + 1249.<br />

Yen Kho-Chiin (ed.), Chhiian Shang-Ku San-Tai Chhin Han San<br />

Kuo Liu Chhao Wen (Complete Collection of prose literature<br />

(including fragments) from remote antiquity through the Chhin<br />

<strong>and</strong> Han Dynasties, the Three Kingdoms, <strong>and</strong> the Six Dynasties),<br />

1836.<br />

Fu Chin-Chhiian (ed.), Cheng Tao Pi Shu Shih Chung (Ten Types<br />

of Secret Books on the Verification of the Tao), early 19th cent.<br />

Encyclopaedia Britanmca.<br />

Yen Chieh (ed.), Huang Chhing Ching Chieh (monographs by Chhing<br />

scholars on classical subjects), 1829, contd. 1860.<br />

Hsiu Chen Shih Shu (Ten Books on the Regeneration of the Primary<br />

Vitalities, physiological alchemy), c. + 1250.<br />

Han Fei, Han Fei Tzu (Book of Master Han Fei), early - 3rd cent.<br />

Su Ching et al. (ed.), Hsin Hsiu Pen Tshao (Newly Improved<br />

Pharmacopoeia), + 659.<br />

Fan Yeh & Ssuma Piao, Hou Han Shu (History of the Later Han<br />

Dynasty), +450.<br />

Liu An et al., HuaiNan Tzu (Book of the Prince of Huai-Nan), - 120.<br />

Taki Mototane, I Chi Khao (Iseki-kO) (Comprehensive Annotated<br />

Bibliography of Chinese Medical Literature [Lost or Still Existing]),<br />

finished c. 1825, pr. 1831; repr. Tokyo 1933, Shanghai 1936.

XXVI<br />

ITCM<br />

K<br />

KCCY<br />

KHTT<br />

Kr<br />

LPC<br />

LS<br />

MCPT<br />

N<br />

NCCS<br />

NCNA<br />

PPT/NP<br />

PPTjWP<br />

PTKM<br />

PWYF<br />

R<br />

RBS<br />

RP<br />

SI<br />

SC<br />

SF<br />

SHC<br />

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS<br />

Wang Khen-Thang & Chu Wen-Chen (ed.), I Tkung Cklng Mo<br />

Ckkiian (Complete Collection of Works on Medicine <strong>and</strong><br />

Sphygmology), + 1601.<br />

Karlgren, B. (I), Grammata Serica (dictionary giving the ancient<br />

forms <strong>and</strong> phonetic values of Chinese characters).<br />

Chhen Yuan-Lung, Ko Chih Ching Yuan (Mirror of Scientific <strong>and</strong><br />

Technological Origins), an encyclopaedia of + 1735.<br />

Chang Yii-Shu (ed.), Khang-Hsi Tzu Tien (Imperial Dictionary of<br />

the Khang-Hsi reign-period), + 1716.<br />

Kraus, P., Le Corpus des Ecrits Jiibiri'ens (MemQires de I'Institut<br />

d'Egypte, 1943, vol. 44, pp. 1-214).<br />

Lung Po-Chien (1), Hsien Tshun Pen Tshao Shu Lu (Bibliographical<br />

Study of Extant Pharmacopoeias <strong>and</strong> Treatises on Natural History<br />

from all Periods).<br />

Tseng Tshao (ed.), Lei Shuo (Classified Commonplace-Book),<br />

+ II3 6.<br />

Shen Kua, Ming Chhi Pi Than (Dream Pool Essays), + 1089.<br />

Nanjio, B., A Catalogue of the Chinese Translations of the Buddhist<br />

Tripifaka, with index by Ross (3).<br />

Hsii Kuang-Chhi, Nung Cheng Chhiian Shu (Complete Treatise on<br />

Agriculture), + 1639.<br />

New China News Agency.<br />

Ko Hung, Pao Phu Tzu (Nei Phien) (Book of the Preservation-of<br />

Solidarity Master; Inner Chapters), c. + 320.<br />

Idem (Wai Phien), the Outer Chapters.<br />

Li Shih-Chen, Pen Tshao Kang Mu (The Great Pharmacopoeia),<br />

+ 1596.<br />

Chang Yii-Shu (ed.), Phei Wen Yiin. Fu (encyclopaedia), + 1711.<br />

Read, Bernard E. et al., Indexes, translations <strong>and</strong> precis of certain<br />

chapters of the Pen Tshao Kang Mu of Li Shih-Chen. If the reference<br />

is to a plant see Read (I); if to a mammalsee Read (2); if to a<br />

bird see Read (3); if to a reptile see Read (4 or 5); if to a mollusc<br />

see Read (5); if to a fish see Read (6); if to an insect see Read (7).<br />

Revue Bibliographique de Sinoiogie.<br />

Read & Pak (I), Index, translation <strong>and</strong> precis of the mineralogical<br />

chapters in the Pen Tshao Kang Mu.<br />

Stein Collection of Tunhuang MSS, British Museum, London,<br />

catalogue number.<br />

Ssuma Chhien, Shih Chi (Historical Records), c. - 90.<br />

Thao Tsung-I (ed.), ShuQ Fu (Florilegium of (Unofficial) Literature).<br />

c. + 1368.<br />

Shan Hat' Ching (Classic of the Mountains <strong>and</strong> Rivers), Chou <strong>and</strong><br />

CJHan.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS<br />

XXVll<br />

SIC<br />

SKCS<br />

SKCSjTMTY<br />

SNPTC<br />

SSIW<br />

STTH<br />

SYEY<br />

TCTC<br />

TFYK<br />

TKKW<br />

TMITC<br />

TPHMF<br />

TPKC<br />

TPYL<br />

TSCC<br />

TSCCIW<br />

Okanishi Tameto, Sung I-Chhien I Chi Khao (Comprehensive<br />

Annotated Bibliography of Chinese Medical Literature in <strong>and</strong><br />

before the Sung Period). Jen-min Wei-sheng, Peking, 1958.<br />

Ssu Khu Chhuan Shu (Complete Library of the Four Categories),<br />

+ 1782; here the reference is to the tshung-shu collection printed<br />

as a selection from one of the seven imperially commissioned<br />

MSS.<br />

Chi Yiin (ed.), Ssu Khu Chhiian Shu Tsung Mu Thi Yao (Analytical<br />

Catalogue of the Complete Library of the Four Categories), + 1782;<br />

the great bibliographical catalogue of the imperial MS. collection<br />

ordered by the Chhien-Lung emperor in + 1772.<br />

Shen Nung Pen Tshao Ching (Classical Pharmacopoeia of the<br />

Heavenly Husb<strong>and</strong>man), CjHan.<br />

Toktaga (Tho-Tho) et al.; Huang Yii-Chi et al. & Hsii Sung et al.<br />

Sung Shih I Wen Chih, Pu, Fu Phien (A Conflation of the Bibliography<br />

<strong>and</strong> Appended Supplementary Bibliographies of the<br />

History of the Sung Dynasty). Corn. Press, Shanghai, 1957.<br />

Wang Chhi, San Tshai Thu Hui (Universal Encyclopaedia), + 1609.<br />

Mei Piao, Shih Yao Erh Ya (The Literary Expositor of Chemical<br />

Physic; or, Synonymic Dictionary of Minerals <strong>and</strong> Drugs), + 806.<br />

Ssuma Kuang, Tzu Chih Thung Chien (Comprehensive Mirror (of<br />

History) for Aid in Government), + 1084.<br />

Wang Chhin-J 0 & Yang I (eds.), TsM Fu Yuan Kuei (Lessons of the<br />

Archives, encyclopaedia), + 1013.<br />

Sung Ying-Hsing, Thien Kung Khai Wu (The Exploitation of the<br />

Works of Nature), + 1637.<br />

Li Hsien (ed.), Ta Ming I Thung Chih (Comprehensive Geography<br />

of the Ming Empire), + 1461.<br />

Thai-Phing Hui Min Ho Chi Chii Fang (St<strong>and</strong>ard Formularies of the<br />

(Government) Great Peace People's Welfare Pharmacies), + II51.<br />

Li Fang (ed.), Thai-Phing Kuang Chi (Copious Records collected in<br />

the Thai-Phing reign-period), + 978.<br />

Li Fang (ed.), Thai-Phing Yu Lan (the Thai-Phing reign-period<br />

(Sung) Imperial Encyclopaedia), + 983.<br />

Chhen Meng-Lei et al. (ed.), Thu Shu Chi Chheng (the Imperial<br />

Encyclopaedia of + 1726). Index by Giles, L. (2).<br />

References to 1884 ed. given by chapter (chuan) <strong>and</strong> page.<br />

References to 1934 photolitho reproduction given by tsM (vol.)<br />

<strong>and</strong> page.<br />

Liu Hsii et al. & Ouyang Hsiu et al.; Thang Shu Ching Chi I Wen Ho<br />

Chih. A conflation of the Bibliographies of the Chiu Thang Shu<br />

by Liu Hsii (HjChin, + 945) <strong>and</strong> the Hsin Thang Shu by Ouyang<br />

Hsiu & Sung Chhi (Sung, + 1061). Corn. Press, Shanghai, 1956.

XXVlll<br />

TSFY<br />

TT<br />

TTC<br />

TTCY<br />

TW<br />

v<br />

WCTYjCC<br />

YCCC<br />

YHL<br />

YHSF<br />

LIST OF ABBREVIA TIONS<br />

Ku Tsu-Yu, Tu Shih Fang Yii Chi Yao (The Historian's Geographical<br />

Companion), begun before + 1666, finished before<br />

+ 1692, but not printed till the end of the eighteenth century<br />

(1796 to 1821).<br />

Wieger, L. (6), Taolsme, vo1. I, Bibliographie Generale (catalogue of<br />

the works contained in the Taoist Patrology, Tao Tsang).<br />

Tao re Ching (Canon of the Tao <strong>and</strong> its Virtue).<br />

Ho Lung-Hsiang & Pheng Han-Jan (ed.). Tao Tsang Chi Yao<br />

(Essentials of the Taoist Patro!ogy), pr. 1906.<br />

Takakusu, J. & Watanabe, K., Tables du TaishO lssaikyo (nouveHe<br />

edition (Japonaise) du Canon bouddhique chinoise), Indexcatalogue<br />

of the Tripitaka.<br />

Verhaeren, H. (2) (ed.), Catalogue de la Bibliotheque du Pe-T' ang<br />

(the Pei Thang Jesuit Library in Peking).<br />

Tseng Kung-Liang (ed.), Wu Ching Tsung Yao (Chhien Chi),<br />

military encyclopaedia, first section, + 1044.<br />

Chang Chiin-Fang (ed.), Yiin Chi Chhi Chhien (Seven Bamboo<br />

Tablets of the Cloudy Satchel), Taoist collection, + 1022.<br />

Thao Hung-Ching (attrib.), Yao Hsing Lun (Discourse on the<br />

Natures <strong>and</strong> Properties of Drugs).<br />

Ma Kuo-Han (ed.), Yii Han Shan Fang CM I Shu (Jade-Box<br />

Mountain Studio collection of (reconstituted <strong>and</strong> sometimes<br />

fragmentary) Lost Books), 1853.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

LIST OF THOSE WHO HAVE KINDLY READ THROUGH SECTIONS IN DRAFT<br />

The following list, which applies only to Vol. 5, pts 2-5, brings up to date those<br />

printed in Vol. I, pp. 15 if., Vol. 2, p. xxiii, Vol. 3, pp. xxxix if., Vol. 4, pt. I, p. xxi,<br />

Vol. 4, pt. 2, p. xli <strong>and</strong> Vol. 4, pt. 3, pp. xliii if.<br />

Dr F. R. Allchin (Cambridge)<br />

Apparatus (alcohol).<br />

Dr M. R. Bloch (Beersheba)<br />

Nitre.<br />

Prof. Derk Bodde (Philadelphia)<br />

Introductions.<br />

Dr C. S. F. Burnett (Cambridge)<br />

Comparative (Latin).<br />

Dr Anthony Butler (St Andrews)<br />

Solutions.<br />

Mr J. Charles (Cambridge)<br />

Metallurgical chemistry.<br />

Mr W. T. Chase (Washington, D.C.) Apparatus.<br />

Prof. A. G. Debus (Chicago)<br />

Modern chemistry (Mao Hua).<br />

The late Prof. A. F. P. Hulsewe (Leiden) Theories.<br />

Dr Edith Jachimowicz (London)<br />

Comparative (Arabic).<br />

Dr Felix Klein-Franke (London)<br />

Comparative (Arabic).<br />

Mr S. W. K. Morgan (Bristol)<br />

Metallurgy (zinc <strong>and</strong> brass).<br />

The late Prof. Ladislao Reti (Milan) Apparatus (alcohol).<br />

Dr Kristofer M. Schipper (Paris)<br />

Theories.<br />

Prof. R. B. Serjeant (Cambridge)<br />

Apparatus (Arabic).<br />

Mr H. J. Sheppard (Warwick)<br />

Introductions, <strong>and</strong> Comparative<br />

(Hellenistic).<br />

Prof. Cyril Stanley Smith (Cambridge, Mass.) Metallurgy, <strong>and</strong> Theories.<br />

Mr Robert Somers (New Haven, Conn.) Theories.<br />

Dr Michel Strickmann (Kyoto)<br />

Theories.<br />

Dr Mikuhis Teich (Cambridge)<br />

Introductions.<br />

Mr H. G. Thurm (Riidesheim-am-Rhein) Ardent Water.<br />

Mr R. G. Wasson (Danbury, Conn.) Introduction (ethno-mycology).<br />

Prof. R. McLachlan Wilson (St Andrews) Comparative (Gnostic), <strong>and</strong> Theories.<br />

Dr John Winter (Washington, D.C.) Apparatus <strong>and</strong> Lacquer.<br />

Mr James Zimmerman (New Haven, Conn.) Theories.

AUTHOR'S NOTE<br />

I T is now some .sixteen years since the preface for Vol. 4 of this series (Physics <strong>and</strong><br />

Physical Technology) was written; since then much has been done towards the later<br />

volumes. We are now happy to present a further substantial part of Vol. 5 (<strong>Spagyrical</strong><br />

<strong>Discovery</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Invention</strong>), i.e. alchemy <strong>and</strong> early chemistry, which go together with<br />

the arts of peace <strong>and</strong> war, including military <strong>and</strong> textile technology, mining, metallurgy<br />

<strong>and</strong> ceramics. The point of this arrangement was explained in the preface of Vol. 4<br />

(e.g. pt. 3, p. 1). Exigences not of logic but of collaboration are making it obligatory<br />

that these other topics should follow rather than precede the central theme of chemistry,<br />

which here is printed as Vol. 5, parts 2,3,4 <strong>and</strong> 5, leaving parts I <strong>and</strong> 6 to appear at a<br />

later date.<br />

The number of physical volumes (parts) which we are now producing may give the<br />

impression that our work is enlarging according to some form of geometrical progression<br />

or along some exponential curve, but this would be largely an illusion, because<br />

in response to the reactions of many friends we are now making a real effort to publish<br />

in books of less thickness, more convenient for reading. At the same time it is true that<br />

over the years the space required for h<strong>and</strong>ling the history of the diverse sciences in<br />

Chinese culture has proved singularly unpredictable. One could (<strong>and</strong> did) at the outset<br />

arrange the sciences in a logical spectrum (mathematics-astronomy-geology<br />

<strong>and</strong> mineralogy-physics-chemistry-biology) leaving estimated room also for all<br />

the technologies associated with them; but to foresee exactly how much space each<br />

one would claim, that, in the words of the Jacobite blessing, was • quite another thing'.<br />

We ourselves are aware that the disproportionate size of some of our Sections may give<br />

a mis-shapen impression to minds enamoured of classical uniformity, but our material<br />

is not easy to • shape', perhaps not capable of it, <strong>and</strong> appropriately enough we are<br />

constrained to follow the Taoist natural irregularity <strong>and</strong> surprise of a romantic garden<br />

rather than to attempt any compression of our lush growths within the geometrical<br />

confines of a Cartesian parterre. The Taoists would have agreed with Richard Baxter<br />

that • 'tis better to go to heaven disorderly than to be damned in due order'. By some<br />

strange chance our spectrum meant (though I thought at the time that the mathematics<br />

was particularly difficult) that the 'easier' sciences were going to come first, those<br />

where both the basic ideas <strong>and</strong> the available source-materials were relatively clear <strong>and</strong><br />

precise. As we proceeded, two phenomena manifested themselves, first the technological<br />

achievements <strong>and</strong> amplifications proved far more formidable than expected (as<br />

was the case in Vol. 4, pts. 2 <strong>and</strong> 3), <strong>and</strong> secondly we found ourselves getting into<br />

ever deeper water, as the saying is, intellectually (as will fully appear in the Sections<br />

on medicine in Vol. 6).<br />

Alchemy <strong>and</strong> early chemistry, the central subjects of the present volume, exemplified<br />

the second of these difficulties well enough, but they have had others of their own.

XXXll<br />

AUTHOR'S NOTE<br />

At one time I almost despaired of ever finding our way successfully through the.<br />

inchoate mass of ideas, <strong>and</strong> the facts so hard to establish, relating to alchemy,<br />

chemistry, metallurgy <strong>and</strong> chemical industry in ancient, medieval <strong>and</strong> traditional<br />

China. The facts indeed were much more difficult to ascertain, <strong>and</strong> also more perplexing<br />

to interpret, than anything encountered in subjects such as astronomy or civil<br />

engineering. And in the end, one must say, we did not get through without cutting<br />

great swathes of briars <strong>and</strong> bracken, as it were, through the muddled thinking <strong>and</strong><br />

confused terminology of the traditional history of alchemy <strong>and</strong> early chemistry in the<br />

West. Here it was indispensable to distinguish alchemy from proto-chemistry <strong>and</strong> to<br />

introduce words of art such as aurifiction, aurifaction <strong>and</strong> macrobiotics. It is also fair<br />

to say that the present subject has been far less well studied <strong>and</strong> understood either by<br />

Westerners or Chinese scholars themselves than fields like astronomy <strong>and</strong> mathematics,<br />

where already in the eighteenth century a Gaubil could do outst<strong>and</strong>ing work,<br />

<strong>and</strong> nearer our own time a Chhen Tsun-Kuei, a de Saussure, <strong>and</strong> a Mikami Yoshio<br />

could set them largely in order. If the study of alchemy <strong>and</strong> early chemistry had<br />

advanced anything like so far, it would be much easier today than it actually is to<br />

differentiate with clarity between the many divergent schools of alchemists at the many<br />

periods, from the - 3rd century to the + 17th, with which we have to deal. More<br />

adequate underst<strong>and</strong>ing would also have been achieved with regard to that crucial<br />

Chinese distinction between inorganic laboratory alchemy <strong>and</strong> physiological alchemy,<br />

the former concerned with elixir preparations of mineral origin, the latter rather with<br />

operations within the adept's own body; a distinction hardly realised to the fun in the<br />

West before the just passed decade. As we shall show in these volumes, there was a<br />

synthesis of these two age-old trends when in iatro-chemistry from the Sung onwards<br />

laboratory methods were applied to physiological substances, producing what we can<br />

only call a proto-biochemistry. But this will be read in its place.<br />

Now a few words on our group of collaborators. Dr Ho Ping-Yli,l since 1972<br />

Professor of Chinese <strong>and</strong> Dean of the Faculty of Asian Studies at Griffith University,<br />

Brisbane, in Queensl<strong>and</strong>, was introduced to readers in Vol. 4 pt. 3, p. Iv; here he has<br />

been responsible for drafting the major part of the sub-section (e) on the history of<br />

alchemy in China. Dr Lu Gwei· DjenZ, my oldest collaborator, dating (in historian's<br />

terms) from 1937, has been involved at all stages of the present volumes, especially<br />

in that seemingly endless mental toil of ours which resulted in the introductory subsections<br />

on concepts, definitions <strong>and</strong> terminology (b), with all that that implies for<br />

theories of alchemy, ideas of immortality, <strong>and</strong> the physiological pathology of the<br />

elixir complex. But her particular domain has been that of physiological alchemy, <strong>and</strong><br />

it was her discoveries, just at the right moment, of what was meant by the three<br />

primary vitalities, mutationist inversion, counter-current flow, <strong>and</strong> such abstruse<br />

matters, which alone permitted the unravelling, at least in the provisional form here<br />

presented (in the relevant sub-section) of that strange <strong>and</strong> unfamiliar system, quasi<br />

Yogistic perhaps, but full of interest for the pre-history of biochemical thought. a<br />

a Some of her findings have appeared separately (Lu Gwei-Djen, 2).<br />

'foJrHi~<br />

• ~fif§';

AUTHOR'S NOTE<br />

XXXlll<br />

A third collaborator is now to be welcomed for the first time, Dr Nathan Sivin,<br />

Professor of Chinese in the University of Pennsylvania at Philadelphia, who has<br />

contributed the sub-section on the general theory of elixir alchemy (h).<br />

Although Prof. Sivin has helped the whole group much by reading over <strong>and</strong><br />

suggesting emendations for all the rest, it is needful to make at this point a proviso<br />

which has not been required in previous volumes. This is that my collaborators cannot<br />

take a collective responsibility for statements, translations or even general nuances,<br />

occurring in parts of the book other than that or those in which they each themselves<br />

directly collaborated. All incoherences <strong>and</strong> contradictions which remain after our long<br />

discussions must be laid at my door, in answer to which I can only say that the state<br />

of the art is as yet very imperfect, that it will certainly be improved by later scholars,<br />

<strong>and</strong> that in the meantime we have done the best we can. If fate had granted to the<br />

four of us the possibility of all working together in one place for half-a-dozen years,<br />

things could have been rather different, but in fact Prof. Ho <strong>and</strong> Prof. Sivin were<br />

never even in Cambridge at one <strong>and</strong> the same time. Thus these volumes have come<br />

into existence the hard way, drafted by different h<strong>and</strong>s at fairly long intervals of time,<br />

<strong>and</strong> still no doubt containing traces of various levels of sophistication <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ing.<br />

a Indeed it would have been reasonable to mark the elixir theory sub-section<br />

'by Nathan Sivin', rather than 'with Nathan Sivin', if it had not been for the fact<br />

that some minor embroideries were offered by me, <strong>and</strong> that a certain part of it, not<br />

perhaps the least interesting, is a revised version of a memoir by Ho Ping-Y ii <strong>and</strong><br />

myself first published in 1959. Lacking the unities of time <strong>and</strong> place, complete credal<br />

unity, . as it were, has been unattainable, but that does not mean that we are not<br />

broadly at one over the main facts <strong>and</strong> problems of the field as a whole; so that<br />

rightly we may be called co-workers.<br />

Besides this I am eager to make certain further acknowledgements. During the<br />

second world war I was instrumental in securing for Cambridge copies of the Tao<br />

Tsang <strong>and</strong> the Tao Tsang Chi Yao. At a somewhat later time (1951-5) Dr Tshao<br />

Thien-Chhin,1 then a Fellow of Caius, made a valuable pioneer study of the alchemical<br />

books in the Taoist Patrology, using a microfilm set in our working collection (now the<br />

East Asian History of Science Library, an educational charity). After his return to the<br />

Biochemical Institute of Academia Sinica, Shanghai, of which he has been in recent<br />

years Vice-Director, these notes were of great help to Dr Ho <strong>and</strong> myself, forming the<br />

ultimate basis for another sub-section (g), on aqueous reactions. Secondly, before he<br />

left Cambridge in 1958, Dr Wang Ling Z accomplished a good work by making an<br />

analytical index of the names <strong>and</strong> synonyms of substances mentioned in the Shih Yao<br />

Erh Ya. Third, when we were faced with the fascinating but difficult study of the<br />

evolution of chemical apparatus in East <strong>and</strong> West, Dr Dorothy Needham put in a<br />

a No less than eight years have now elapsed since Prof. Sivin first drafted the theoretical sub-section<br />

in this volume, <strong>and</strong> it could hardly be expected that during such a period insights <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

would not mature <strong>and</strong> grow. Consequently this material should be supplemented by reference to Sivin<br />

(14), which gives a concise summary of his present views.

xxxiv<br />

AUTHOR'S NOTE<br />

considerable amount of work, including some drafting, in what happened to be<br />

a convenient interval in work on her own book on the history of muscle biochemistry,<br />

Machina Carnis. She has also read all our pages-perhaps the only person in the world<br />

who ever does so!<br />

While readers of sub-sections in typescript <strong>and</strong> proof have not been as numerous,<br />

perhaps, as for previous volumes, a special debt of gratitude is due to Mr J. A. Charles<br />

of St John's College, chemist, metallurgist <strong>and</strong> archaeologist, whose advice to Prof. Ho<br />

<strong>and</strong> myself from the earliest days was extremely precious. Valuable consultations also<br />

took place with Mr H. J. Sheppard of Warwick, especially during his time in<br />

Cambridge as a Schoolmaster-Fellow of Churchill College. The late Dr Ladislao Red<br />

was prodigal in his helpful advice on all aspects of the history of distillation, based on<br />

a lifetime's experience in chemical industry. Dr F. R. Al1chin later communicated to<br />

us valuable unpublished information on the G<strong>and</strong>haran stills of Taxila <strong>and</strong> PushkaHivatL<br />

Subsequently we were able to benefit by an extensive correspondence on<br />

spirit production with l\Ir H. G. Thurm of the Asbach Distillery at Rl1desheim-am<br />

Rhein; while Prof. E. J. Wiesenberg of London guided us with great expertise through<br />

the labyrinths of possible Semitic connections with the origin of the root' chem-'. Few<br />

chemists in Cambridge, by some chance, happen to be interested at the present time in<br />

the history of their subject, but if Dr A. J. Berry <strong>and</strong> Prof. J. R. Partington had lived<br />

we could have profited greatly from their help. With the latter, indeed, we did have<br />

fruitful <strong>and</strong> most friendly contact, but it was in connection mainly with the gunpowder<br />

epic, Prof. Wang Ling <strong>and</strong> I endeavouring, not unsuccessfuIIy, to convince<br />

him of the real <strong>and</strong> major contribution of China in that field; those were days however<br />

before any word of the present volumes had been written. In 1968, wen after it had<br />

been started, there was convened the First Conference of Taoist Studies at the Villa<br />

SerbeUoni at BeIlagio on Lake Coma; Ho Ping-Y 11, N athan Sivin <strong>and</strong> myself were an<br />

of the party, <strong>and</strong> here much stimulus was obtained from that remarkable Tao shin<br />

Kristofer Schipper-hence the unexpected sub-section on liturgiology <strong>and</strong> alchemical<br />

origins in our introductory material (b). In addition to the invaluable advice of many<br />

other colleag"ues in particular areas, we record especially the kindness of Professor<br />

Cyril Stanley Smith in commenting upon the sub-sections on metallurgy (c) <strong>and</strong> on<br />

the theory of elixir alchemy (h). Dr N. Sivin also expresses gratitude to Prof. A. F. P.<br />

Hulsewe <strong>and</strong> his staff for the open-hearted hospitality which they gave him during the<br />

gestation of the latter study, carried out almost entirely at the Sinologisch Instituut,<br />

Leiden.<br />

It is right to record that certain parts of these volumes have been given as lectures<br />

to bodies honouring us by such invitations. Thus various excerpts from the introductory<br />

sub-sections on concepts, terminology <strong>and</strong> definitions, were given for the<br />

Rapkine Lecture at the Pasteur Institute in Paris (1970) <strong>and</strong> the BernaI Lecture at<br />

Birkbeck College in London in the following year. Portions of the historical subsections,<br />

especially that on the coming of modern chemistry, were used for the Ballard<br />

Matthews Lectures of the University of Wales at Bangor. A considerable part of the<br />

physiological alchemy material formed the basis of the Fremantle Lectures at Bailiol

AUTHOR'S NOTE<br />

xxxv<br />

College, Oxford, a <strong>and</strong> had been given more briefly as the Harvey Lecture to the<br />

Harveian Society of London the year before. Four lectures covering the four present<br />

parts of this volume were given at the College de France in Paris at Easter, 1973, in<br />

fulfilment of my duties as Professeur Etranger of that noble institution. Lastly, the<br />

contrasts between Hellenistic proto-chemistry <strong>and</strong> Chinese alchemy, with the spread<br />

of the elixir concept from China throughout the Old World, were expounded at the<br />

Universities of Hongkong <strong>and</strong> at the University of British Columbia at Vancouver,<br />

in 1975; while further aspects of the chemical relationships of the civilisations, east<br />

<strong>and</strong> west, formed the subject of the Bowra Lecture at Wad ham College, Oxford, in<br />

1976.<br />

If there is one question more than any other raised by this present Section 33 on<br />

alchemy <strong>and</strong> early chemistry, now offered to the republic of learning in these volumes,<br />

it is that of human unity <strong>and</strong> continuity. In the light of what is here set forth, can we<br />

allow ourselves to visualise that some day before long we shall be able to write the<br />

history of man's enquiry into chemical phenomena as one single development<br />

throughout the Old World cultures? Granted that there were several different foci of<br />

ancient metallurgy <strong>and</strong> primitive chemical industry, how far was the gradual flowering<br />

of alchemy <strong>and</strong> chemistry a single endeavour, running contagiously from one civilisation<br />

to another?<br />

It is a commonplace of thought that some forms of human experience seem to have<br />

progressed in a more obvious <strong>and</strong> palpable way than others. It might be difficult to<br />

say how Michael Angelo could be considered an improvement on Pheidias, or Dante<br />

on Homer, but it can hardly be questioned that Newton <strong>and</strong> Pasteur <strong>and</strong> Einstein did<br />

really know a great deal more about the natural univers e than Aristotle or Chan g Heng.<br />

This must tell us something about the differences between art <strong>and</strong> religion on one<br />

side <strong>and</strong> science on the other, though no one seems able to explain quite what, but in<br />

any case within the field of natural knowledge we cannot but recognise an evolutionary<br />

development, a real progress, over the ages. The cultures might be many, the languages<br />

diverse, but they all partook of the same quest.<br />

Throughout this series of volumes it has been assumed all along that there is only<br />

one unitary science of Nature, approached more or less closely, built up more or less<br />

successfully <strong>and</strong> continuously, by various groups of mankind from time to time. This<br />

means that one can expect to trace an absolute continuity between the first beginnings<br />

of astronomy <strong>and</strong> medicine in Ancient Babylonia, through the advancing natural<br />

knowledge of medieval China, India, Islam <strong>and</strong> the classical Western world, to the<br />

break-through of late Renaissance Europe when, as has been said, the most effective<br />

method of discovery was itself discovered. Many people probably share this point of<br />

view, but there is another one which I may associate with the name of Oswald<br />

Spengler, the German world-historian of the thirties whose works, especially The<br />

Decline of the West, achieved much popularity for a time. According to him, the<br />

sciences produced by different civilisations were like separate <strong>and</strong> irreconcilable works<br />

a The relevant volume is therefore offered to the Trustees of the late Sir Francis Fremantle's<br />

benefaction in discharge of the duty of publication of his Lectures.

XXXVI<br />

AUTHOR'S NOTE<br />

of art, valid only within their own frames of reference, <strong>and</strong> not subsumable into a<br />

single history <strong>and</strong> a single ever-growing structure.<br />

Anyone who has felt the influence of Spengler retains, I think, some respect for the<br />

picture he drew of the rise <strong>and</strong> fall of particular civilisations <strong>and</strong> cultures, resembling<br />

the birth, flourishing <strong>and</strong> decay of individual biological organisms, in human or animal<br />

life-cycles. Certainly I could not refuse all sympathy for a point of view so like that of<br />

the Taoist philosophers, who always emphasised the cycles of life <strong>and</strong> death in Nature,<br />

a point of view that Chuang Chou himself might weH have shared. Yet while one can<br />

easily see that artistic styles <strong>and</strong> expressions, religious ceremonies <strong>and</strong> doctrines, or<br />

different kinds of music, have tended to be incommensurable; for mathematics,<br />

science <strong>and</strong> technology the case is altered-man has always lived in an environment<br />

essentially constant in its properties, <strong>and</strong> his knowledge of it, if true, must therefore<br />

tend towards a constant structure.<br />

This point would not perhaps need emphasis if certain scholars, in their anxiety to<br />

do justice to the differences between the ancient Egyptian or the medieval Chinese,<br />

Arabic or Indian world-views <strong>and</strong> our own, were not sometimes tempted to foUow<br />

lines of thought which might lead to Spenglerian pessimism. a Pessimism I say,<br />

because of course he did prophesy the decline <strong>and</strong> fall of modern scientific civilisation.<br />

For example, our own collaborator, Nathan Sivin, has often pointed out, quite rightly,<br />

that for medieval <strong>and</strong> traditional China • biology' was not a separated <strong>and</strong> defined<br />

science. One gets its ideas <strong>and</strong> facts from philosophical writings, books on· pharmaceutical<br />

natural history, treatises on agriculture <strong>and</strong> horticulture, monographs on<br />

groups of natural objects, miscellaneous memor<strong>and</strong>a <strong>and</strong> so on. He urged that to<br />

speak without reservations of ' Chinese biology' would be to imply a structure which<br />

historically did not exist, disregarding mental patterns which did exist. Taking such<br />

artificial rubrics too seriously would also imply the natural but perhaps erroneous<br />

assumption that medieval Chinese scientists were asking the same questions about the<br />

living world as their modern counterparts in the West, <strong>and</strong> merely chanced, through<br />

some quirk of national character, language, economics, scientific method or social<br />

structure, to find different answers. On this approach it would not occur to one to<br />

investigate what questions the ancient <strong>and</strong> medieval Chinese scientists themselves<br />

were under the impression that they were asking. A fruitful comparative history of<br />

science would have to be founded not on the counting up of isolated discoveries,<br />

a Just recently a relevant polemical discussion has been going on among geologists. Harrington (I, 2),<br />

who had traced interesting geological insights in Herodotus <strong>and</strong> Isaiah, was taken to task by Could (1),<br />

maintaining that 'science is no march to truth, but a series of conceptual schemes each adaJ>ted to a<br />

prevailing culture', <strong>and</strong> that progress consists in the mutation of these schemes, new coneepts of<br />

creative thinkers resolving anomalies of old theories into new systems of belief. This was evidently a<br />

Kuhnian approach, but no such formulation will adequately account for the gradual percolatton of true<br />

knowledge through the successive civilisations, <strong>and</strong> its general accumulation. Harrington himself, in<br />

his reply (3), maintained that 'there is a singular state of Nature towards which all estimatC$ of reality<br />

converge', <strong>and</strong> therefore that we can <strong>and</strong> should judge the insights of the ancients on the basis of our<br />

own knowledge of Nature, while at the same time making every effort to underst<strong>and</strong> their intellectual<br />

framework. In illustration he took the medieval Chinese appreciation of the meaning of fos$il remains<br />