The Syntax of Givenness Ivona Kucerová

The Syntax of Givenness Ivona Kucerová

The Syntax of Givenness Ivona Kucerová

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

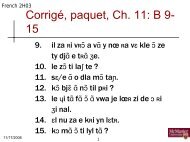

(23) What can be understood as new?<br />

a. (i) What did Marie give to Pavel?<br />

(ii) Marie dala Pavlovi [facku] New ←− slap<br />

b. (i) What did Marie give to whom?<br />

(ii) Marie dala [Pavlovi facku] New ←− Pavel a slap<br />

c. (i) What did Marie do?<br />

(ii) Marie [dala Pavlovi facku] New ←− gave Pavel a slap<br />

d. (i) What happened?<br />

(ii) [Marie dala Pavlovi facku] New ←− Marie gave Pavel a slap<br />

In contrast, if an utterance contains any deviance from the basic order, then such an utterance<br />

is infelicitous in an all-new context. It means that if any reordering takes place,<br />

at least one constituent must be α G , i.e., introduced in the previous discourse. In other<br />

words, any reordering limits the number <strong>of</strong> structural positions in which we can identify<br />

the partition between given and new. For example, in a derived word order, as in (24), there<br />

is only one felicitous interpretation <strong>of</strong> the information structure. More precisely, only the<br />

rightmost constituent can be interpreted as new (non-G). In this particular case, it is the<br />

indirect object Pavel. Thus, in (24) there is only one possible partition between given and<br />

new, in contrast to (22) that is compatible with several partitions, as schematized in (25).<br />

(24) Focus Projection within a derived word order:<br />

a. Marie dala facku [Pavlovi] New ←− S V DO || IO t DO<br />

b. #Marie dala [facku Pavlovi] New<br />

c. #Marie [dala facku Pavlovi] New<br />

d. #[Marie dala facku Pavlovi] New<br />

(25) a. Marie dala facku || Pavlovi.<br />

b. (||) Marie (||) dala (||) Pavlovi (||) facku.<br />

What we can learn from the observed pattern is that in basic word order there is a relative<br />

freedom in what parts <strong>of</strong> the utterance can be interpreted as new and what parts can be interpreted<br />

as given. As I have already anticipated in the previous discussion <strong>of</strong> G-movement,<br />

this pattern can be described in the following manner: whatever is interpreted as given cannot<br />

be linearly preceded by anything interpreted as new.<br />

Let’s now turn to the question <strong>of</strong> how exactly the multiple partition effect follows from<br />

our system. To see that, we will look at a very simple case: a transitive clause that has no<br />

modifiers, only a subject, a verb, and an object. Consider first the case where the subject is<br />

the only given element. As we already know, the resulting word order is SVO, as seen in<br />

(26) and (27). 16<br />

(26) a. Subject-G verb Object ←−<br />

b. #Object verb Subject-G<br />

16 I use here examples with potom ‘then, afterward’ instead <strong>of</strong> a wh-question. <strong>The</strong> reason is that potom<br />

creates a natural context where only the subject is presupposed/given. For reasons that are not clear to me, it<br />

is difficult to obtain the same pragmatic effect with a wh-question.<br />

19