The Syntax of Givenness Ivona Kucerová

The Syntax of Givenness Ivona Kucerová

The Syntax of Givenness Ivona Kucerová

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

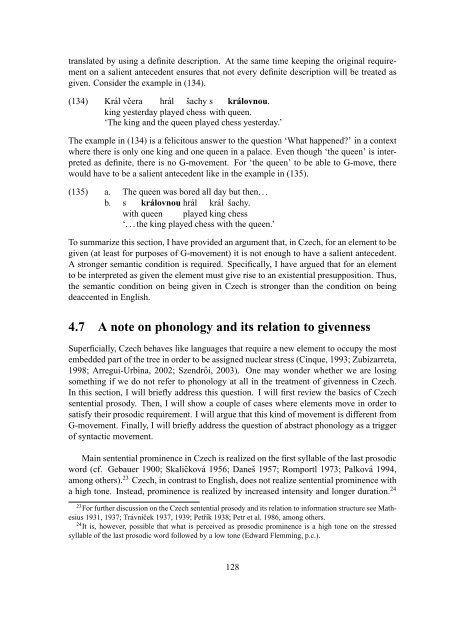

translated by using a definite description. At the same time keeping the original requirement<br />

on a salient antecedent ensures that not every definite description will be treated as<br />

given. Consider the example in (134).<br />

(134) Král včera hrál šachy s královnou.<br />

king yesterday played chess with queen.<br />

‘<strong>The</strong> king and the queen played chess yesterday.’<br />

<strong>The</strong> example in (134) is a felicitous answer to the question ‘What happened?’ in a context<br />

where there is only one king and one queen in a palace. Even though ‘the queen’ is interpreted<br />

as definite, there is no G-movement. For ‘the queen’ to be able to G-move, there<br />

would have to be a salient antecedent like in the example in (135).<br />

(135) a. <strong>The</strong> queen was bored all day but then. . .<br />

b. s královnou hrál král šachy.<br />

with queen played king chess<br />

‘. . . the king played chess with the queen.’<br />

To summarize this section, I have provided an argument that, in Czech, for an element to be<br />

given (at least for purposes <strong>of</strong> G-movement) it is not enough to have a salient antecedent.<br />

A stronger semantic condition is required. Specifically, I have argued that for an element<br />

to be interpreted as given the element must give rise to an existential presupposition. Thus,<br />

the semantic condition on being given in Czech is stronger than the condition on being<br />

deaccented in English.<br />

4.7 A note on phonology and its relation to givenness<br />

Superficially, Czech behaves like languages that require a new element to occupy the most<br />

embedded part <strong>of</strong> the tree in order to be assigned nuclear stress (Cinque, 1993; Zubizarreta,<br />

1998; Arregui-Urbina, 2002; Szendrői, 2003). One may wonder whether we are losing<br />

something if we do not refer to phonology at all in the treatment <strong>of</strong> givenness in Czech.<br />

In this section, I will briefly address this question. I will first review the basics <strong>of</strong> Czech<br />

sentential prosody. <strong>The</strong>n, I will show a couple <strong>of</strong> cases where elements move in order to<br />

satisfy their prosodic requirement. I will argue that this kind <strong>of</strong> movement is different from<br />

G-movement. Finally, I will briefly address the question <strong>of</strong> abstract phonology as a trigger<br />

<strong>of</strong> syntactic movement.<br />

Main sentential prominence in Czech is realized on the first syllable <strong>of</strong> the last prosodic<br />

word (cf. Gebauer 1900; Skaličková 1956; Daneš 1957; Romportl 1973; Palková 1994,<br />

among others). 23 Czech, in contrast to English, does not realize sentential prominence with<br />

a high tone. Instead, prominence is realized by increased intensity and longer duration. 24<br />

23 For further discussion on the Czech sentential prosody and its relation to information structure see Mathesius<br />

1931, 1937; Trávníček 1937, 1939; Petřík 1938; Petr et al. 1986, among others.<br />

24 It is, however, possible that what is perceived as prosodic prominence is a high tone on the stressed<br />

syllable <strong>of</strong> the last prosodic word followed by a low tone (Edward Flemming, p.c.).<br />

128