From FUS to Fibs: What's New in Frontotemporal ... - IOS Press

From FUS to Fibs: What's New in Frontotemporal ... - IOS Press

From FUS to Fibs: What's New in Frontotemporal ... - IOS Press

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 21 (2010) 349–360 349<br />

DOI 10.3233/JAD-2010-091513<br />

<strong>IOS</strong> <strong>Press</strong><br />

Review<br />

<strong>From</strong> <strong>FUS</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Fibs</strong>: What’s <strong>New</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia?<br />

James R. Burrell a,b and John R. Hodges a,∗<br />

a Pr<strong>in</strong>ce of Wales Medical Research Institute, University of <strong>New</strong> South Wales, Sydney, Australia<br />

b Pr<strong>in</strong>ce of Wales Cl<strong>in</strong>ical School, University of <strong>New</strong> South Wales, Sydney, Australia<br />

Accepted 1 February 2010<br />

Abstract. Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia (FTD) is an important cause of non-Alzheimer’s dementia and is the second most common<br />

cause of young onset dementia. FTD presents with progressive changes <strong>in</strong> behavior and personality (behavioral variant FTD)<br />

or language deficits (also known as primary progressive aphasia), although both commonly coexist. Patients with progressive<br />

aphasia are subclassified accord<strong>in</strong>g <strong>to</strong> the pattern of language deficits <strong>in</strong><strong>to</strong> those with progressive non-fluent aphasia (PNFA)<br />

and semantic dementia (SD). FTD is pathologically heterogeneous, both macroscopically and on a molecular level, with tau<br />

positive, TDP-43 positive, and <strong>FUS</strong> positive <strong>in</strong>traneuronal <strong>in</strong>clusions recognized on immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical analysis. TDP-43<br />

positive <strong>in</strong>clusions are also a feature of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis pathology, corroborat<strong>in</strong>g the observation of overlapp<strong>in</strong>g<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical features between the two conditions and reaffirm<strong>in</strong>g the FTD-ALS disease spectrum. Most FTD cases are sporadic, but an<br />

important m<strong>in</strong>ority is <strong>in</strong>herited <strong>in</strong> an au<strong>to</strong>somal dom<strong>in</strong>ant fashion, most commonly due <strong>to</strong> MAPT or progranul<strong>in</strong> gene mutations.<br />

Familial clusters of FTD and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis are also recognized but poorly unders<strong>to</strong>od. This paper reviews the<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical phenotypes, assessment and treatment of FTD <strong>in</strong> light of recent pathological and genetic discoveries.<br />

Keywords: Behavioral variant FTD, fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia, FTD-ALS, progressive non-fluent aphasia, semantic dementia, tau,<br />

TDP-43<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

The recent demonstration of TAR-DNA b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong><br />

43 (TDP-43) as the constituent of ubiqu<strong>in</strong>tated<br />

<strong>in</strong>traneuronal <strong>in</strong>clusions <strong>in</strong> fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia<br />

(FTD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) has<br />

stimulated a surge of cl<strong>in</strong>ical, pathological, and genetic<br />

research <strong>in</strong><strong>to</strong> these overlapp<strong>in</strong>g entities. FTD is the second<br />

most common cause of young onset dementia after<br />

Alzheimer’s disease [1,2], and three dist<strong>in</strong>ct cl<strong>in</strong>ical<br />

phenotypes of FTD are recognized, each with variable<br />

degrees of progressive behavior and language distur-<br />

∗ Correspondence <strong>to</strong>: Prof. John R. Hodges, Pr<strong>in</strong>ce of Wales<br />

Medical Research Institute, Cnr Barker St and Easy St, Randwick,<br />

Sydney, NSW 2031, Australia. Tel.: +61 2 9399 1132; Fax: +61 2<br />

9399 1005; E-mail: j.hodges@powmri.edu.au.<br />

ISSN 1387-2877/10/$27.50 © 2010 – <strong>IOS</strong> <strong>Press</strong> and the authors. All rights reserved<br />

bance. A proportion of patients with FTD also develop<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical and neurophysiological evidence of mo<strong>to</strong>r<br />

neuron dysfunction and many satisfy the El Escorial<br />

criteria for the diagnosis of ALS [3]. The pathology<br />

of FTD is heterogeneous with variable degrees of focal<br />

frontal and temporal atrophy [4]. Three <strong>in</strong>traneuronal<br />

<strong>in</strong>clusions types have been characterized immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemically<br />

as tau, TDP-43 or fused <strong>in</strong> sarcoma (<strong>FUS</strong>)<br />

positive [5–8]. TDP-43 positive <strong>in</strong>clusions are the most<br />

common type <strong>in</strong> FTD and are also identified <strong>in</strong> the<br />

majority of ALS cases [9,10].<br />

Until recently, FTD was considered a rare cause of<br />

dementia and cl<strong>in</strong>ical dist<strong>in</strong>ction from AD was considered<br />

very difficult [11,12]. Over time, the def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical features of FTD have been elucidated and<br />

three cl<strong>in</strong>ical phenotypes are recognized (see Fig. 1).<br />

The behavioral variant of FTD (bvFTD) is character-

350 J.R. Burrell and J.R. Hodges / <strong>From</strong> <strong>FUS</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Fibs</strong>: What’s <strong>New</strong> <strong>in</strong> Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia?<br />

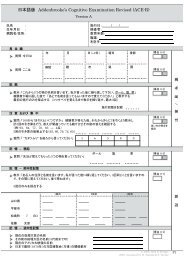

Fig. 1. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Phenotypes of FTD. FTD is subclassified as behavioral variant (bvFTD) if behavior and personality changes predom<strong>in</strong>ate; Tau<br />

(green) and TDP-43 (blue) pathology are equally prevalent. Language variants <strong>in</strong>clude progressive non-fluent aphasia (PNFA), <strong>in</strong> which tau<br />

pathology is most prevalent and semantic dementia (SD), <strong>in</strong> which TDP-43 pathology is almost universal.<br />

Fig. 2. MRI appearances <strong>in</strong> FTD. T1 weighted, coronal MRI images reveal: A) bvFTD – dorsolateral and orbi<strong>to</strong>mesial, bifrontal atrophy, with<br />

dilatation of anterior horns of lateral ventricles (left > right); B) PNFA – moderate temporal atrophy (left > right) with subtle enlargement of<br />

the sylvian fissure due <strong>to</strong> <strong>in</strong>sula atrophy (s<strong>in</strong>gle arrow); C) SD – anterior temporal atrophy, severe on the left (double arrow) and moderate on the<br />

right with associated orbi<strong>to</strong>frontal atrophy.<br />

ized by marked changes <strong>in</strong> behavior and personality,<br />

with relatively preserved language function. Alternatively,<br />

patients with semantic dementia (SD) and progressive<br />

non-fluent aphasia (PNFA) develop progressive<br />

language deficits, with more subtle personality and<br />

behavior changes. FTD is a progressive neurodegenerative<br />

disorder and the median survival from symp<strong>to</strong>m<br />

onset is 6–8 years, but patients with FTD and ALS have<br />

an even worse prognosis [13,14].<br />

This review cannot cover every facet of this rapidly<br />

evolv<strong>in</strong>g field, but rather attempts <strong>to</strong> place the recent<br />

pathological and genetic discoveries with<strong>in</strong> the context<br />

of the cl<strong>in</strong>ical phenotypes of FTD and <strong>to</strong> outl<strong>in</strong>e an<br />

approach <strong>to</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical assessment and treatment.<br />

PATHOLOGY<br />

Focal frontal and temporal atrophy is identified <strong>in</strong><br />

patients with FTD on au<strong>to</strong>psy [4], but the pattern of<br />

atrophy varies significantly among the cl<strong>in</strong>ical phenotypes.<br />

Bilateral mesial and orbi<strong>to</strong>frontal and temporal<br />

atrophy is the characteristic f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> patients with<br />

bvFTD. In SD, anterior and <strong>in</strong>ferior temporal lobe atrophy<br />

is a universal feature, usually worse on the left<br />

than the right [15,16]. There may also be mild frontal<br />

atrophy. In PFNA, left-sided <strong>in</strong>ferior frontal, <strong>in</strong>sula,<br />

and perisylvian atrophy, is characteristic and is often<br />

severe [17].

J.R. Burrell and J.R. Hodges / <strong>From</strong> <strong>FUS</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Fibs</strong>: What’s <strong>New</strong> <strong>in</strong> Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia? 351<br />

Microscopically, FTLD is characterized by microvacuolation<br />

and neuronal loss, with variable degrees<br />

of white matter myel<strong>in</strong> loss and astrocytic gliosis<br />

[4], and <strong>in</strong>traneuronal as well as <strong>in</strong>traglial <strong>in</strong>clusions.<br />

The use of immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g has<br />

revolutionized the field and allows further categorization<br />

of the molecular pathology. Tau positive <strong>in</strong>clusions<br />

are present <strong>in</strong> approximately 40% of FTLD cases<br />

and the rema<strong>in</strong>der are tau negative but ubiquit<strong>in</strong> positive<br />

[18]. Tau positive cases can be characterized biochemically<br />

as either predom<strong>in</strong>antly three microtubule<br />

b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g repeats tau (3R tau) or four microtubule b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g<br />

repeat (4R tau), with further subclassification based<br />

on established morphologic criteria [4,19]. TDP-43<br />

accounts for the majority of the ubiquit<strong>in</strong> positive cases<br />

and more than half of all FTD cases overall, but<br />

a m<strong>in</strong>ority FTD cases are both tau and TDP-43 negative<br />

[10]. Very recently, <strong>FUS</strong> positive <strong>in</strong>clusions have<br />

been demonstrated <strong>in</strong> these cases [6]. The search for<br />

<strong>FUS</strong> pathology was only <strong>in</strong>itiated after <strong>FUS</strong> gene mutations<br />

were identified <strong>in</strong> cases of familial ALS, further<br />

emphasiz<strong>in</strong>g the l<strong>in</strong>ks between FTD and MND [20–<br />

23]. Ubiquit<strong>in</strong> positive, TDP-43 negative <strong>in</strong>clusions<br />

have recently been demonstrated <strong>in</strong> patients with ALS<br />

due <strong>to</strong> mutations of <strong>FUS</strong> [24]. TDP-43 and <strong>FUS</strong> are<br />

RNA process<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong>s, however, the l<strong>in</strong>k between<br />

these mutations and disease pathogenesis has not yet<br />

been elucidated [25].<br />

The cl<strong>in</strong>ical phenotypes are associated with specific<br />

molecular pathologies <strong>to</strong> variable degrees. Tau positive<br />

and TDP-43 positive <strong>in</strong>clusions are equally prevalent <strong>in</strong><br />

patients with bvFTD, whereas SD as well as FTD cases<br />

with coexistent ALS, are almost exclusively associated<br />

with TDP-43 pathology, although the distribution of<br />

<strong>in</strong>clusions differs between phenotypes [15,19,26,27].<br />

In PNFA, tau positive <strong>in</strong>clusions are most commonly<br />

identified and can be further classified his<strong>to</strong>pathologically<br />

as Pick’s disease (PiD) or non-PiD tau [26–28].<br />

The small number of reported <strong>FUS</strong> positive FTD cases<br />

thus far have presented with bvFTD [6,29].<br />

GENETICS<br />

Up <strong>to</strong> 40% of patients with FTD may have a family<br />

his<strong>to</strong>ry of dementia [1,30,31], but the high community<br />

prevalence of non-FTD dementia may account for a<br />

significant proportion of this family his<strong>to</strong>ry. Patients<br />

with an au<strong>to</strong>somal dom<strong>in</strong>ant pattern (several affected<br />

first degree relatives across two generations) are much<br />

rarer, perhaps only account<strong>in</strong>g for 10% of FTD cas-<br />

es [32]. Known mutations can now be demonstrated<br />

<strong>in</strong> the majority of patients with this pattern of <strong>in</strong>heritance.<br />

Overall, mutations of the microtubule associated<br />

phosphoprote<strong>in</strong> tau (MAPT) and the progranul<strong>in</strong><br />

(PRGN) gene each account for 5–11% of <strong>to</strong>tal FTD cases<br />

[32–35]. Although associated with TDP-43 pathology,<br />

PGRN mutations are not usually identified <strong>in</strong> patients<br />

with familial ALS [36]. Mutations of the gene<br />

encod<strong>in</strong>g for TDP-43 (TARBP), recognized as a cause<br />

of familial ALS, have also been identified <strong>in</strong> cases of<br />

FTD-ALS [37], and rarely <strong>in</strong> FTD [38]. Rare genetic<br />

mutations caus<strong>in</strong>g FTD <strong>in</strong>clude valos<strong>in</strong> conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong><br />

(VCP) and charged multivesicular body prote<strong>in</strong> 2B<br />

(CHMP-2B). Mutation <strong>in</strong> the VCP gene causes FTD <strong>in</strong><br />

association with <strong>in</strong>clusion body myopathy and Paget<br />

disease of bone [39], whereas the CHMP-2B gene mutation<br />

is conf<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>to</strong> a large Danish cohort with FTD<br />

and other very rare patients with ALS [40]. In a recent<br />

study of patients with familial ALS due <strong>to</strong> <strong>FUS</strong> mutations,<br />

one mutation carrier presented with FTD [24].<br />

The overall <strong>in</strong>cidence of <strong>FUS</strong> mutations <strong>in</strong> FTD patients<br />

is currently unknown, however, no cases were<br />

identified <strong>in</strong> a recent mutation screen<strong>in</strong>g study of 225<br />

FTD patients [32].<br />

In addition <strong>to</strong> au<strong>to</strong>somal dom<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>in</strong>heritance of<br />

FTD, familial clusters of FTD and ALS are reported.<br />

With<strong>in</strong> these clusters, one <strong>in</strong>dividual may develop FTD<br />

and another ALS, or a third <strong>in</strong>dividual may develop<br />

FTD and subsequently ALS. Several l<strong>in</strong>kage studies of<br />

FTD-ALS clusters have <strong>in</strong>dicated a common locus <strong>in</strong><br />

the region of chromosome 9p13.2–21.3 [41–44], but<br />

the responsible gene has not yet been identified.<br />

CLINICAL PHENOTYPES OF FTD<br />

Behavioral variant FTD<br />

Approximately half of patients with FTD present<br />

with the bvFTD [45]. The symp<strong>to</strong>m profile reflects progressive<br />

dis<strong>in</strong>tegration of the neural circuits <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong><br />

social cognition, emotion regulation, motivation, and<br />

decision mak<strong>in</strong>g [46–48]. The orbi<strong>to</strong>mesial frontal cortex,<br />

<strong>in</strong>sula, and amygdala are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly recognized<br />

as key structures undergo<strong>in</strong>g degeneration [49]. The<br />

behavioral and personality changes of bvFTD develop<br />

<strong>in</strong>sidiously and may <strong>in</strong>itially be mistaken for symp<strong>to</strong>ms<br />

of depression [50,51]. Over time, symp<strong>to</strong>ms accumulate<br />

and become more obvious. Patients usually lack<br />

<strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong><strong>to</strong> their cognitive symp<strong>to</strong>ms and often dismiss<br />

carer or family concerns as unfounded. Apathy is al-

352 J.R. Burrell and J.R. Hodges / <strong>From</strong> <strong>FUS</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Fibs</strong>: What’s <strong>New</strong> <strong>in</strong> Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia?<br />

most universal and manifests as <strong>in</strong>ertia, reduced motivation,<br />

lack of <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> previous hobbies, and progressive<br />

social isolation. Dis<strong>in</strong>hibition often coexists<br />

with apathy, and may manifest as impulsive actions,<br />

tactless or sexually <strong>in</strong>appropriate remarks, and socially<br />

embarrass<strong>in</strong>g behavior. Changes <strong>in</strong> eat<strong>in</strong>g habits are<br />

common, with a narrowed reper<strong>to</strong>ire of favored foods<br />

and meals. Patients may become glut<strong>to</strong>nous with food<br />

hoarded and even snatched from others. Excessive<br />

weight ga<strong>in</strong> is common. Repetitive or stereotypic behaviors<br />

may be apparent and patients may perseverate,<br />

frequently repeat<strong>in</strong>g phrases, s<strong>to</strong>ries or favorite jokes.<br />

Patients often lack empathy and an <strong>in</strong>appropriately subdued<br />

grief reaction is a common early symp<strong>to</strong>m. Mental<br />

rigidity is common and patients may have difficulty<br />

adapt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>to</strong> new situations or rout<strong>in</strong>es. Psychotic<br />

features (delusions and or halluc<strong>in</strong>ations) are relatively<br />

unusual overall [52], but <strong>in</strong> cases of FTD associated<br />

with ALS psychotic features have been reported <strong>in</strong> up<br />

<strong>to</strong> 50% of patients [53]. Uncommonly, patients may<br />

present with symp<strong>to</strong>ms suggestive of dementia with<br />

Lewy bodies such as halluc<strong>in</strong>ations, fluctuat<strong>in</strong>g cognition,<br />

and park<strong>in</strong>sonism [54].<br />

Language disturbance may be present, most commonly<br />

characterized by adynamism, but does not dom<strong>in</strong>ate<br />

the cl<strong>in</strong>ical picture. Impaired executive function,<br />

manifest as difficulties <strong>in</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>g, organization, and<br />

goal-sett<strong>in</strong>g, is common. Unlike AD, episodic memory<br />

is preserved <strong>in</strong> the early stages of bvFTD and visuospatial<br />

deficits are not prom<strong>in</strong>ent.<br />

It is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly apparent that not all patients with<br />

the cl<strong>in</strong>ical features of bvFTD actually progress <strong>to</strong> frank<br />

dementia [55]. Such patients are almost always men<br />

and a proportion rema<strong>in</strong> stable over many years or<br />

actually improve [56,57]. Over recent years a number<br />

of features have emerged that dist<strong>in</strong>guish these<br />

non-progressive or phenocopy cases, for example, they<br />

show normal structural and functional imag<strong>in</strong>g bra<strong>in</strong><br />

imag<strong>in</strong>g [55,56,58]. The etiology of the phenocopy<br />

syndrome is a matter of debate. A proportion of patients<br />

appear <strong>to</strong> have a developmental personality disorder<br />

<strong>in</strong> the Asperger’s spectrum (personal observation).<br />

Some may have a chronic low grade mood disorder, but<br />

others rema<strong>in</strong> a mystery.<br />

The most commonly used diagnostic criteria for<br />

bvFTD, the Neary criteria [59], have recently come under<br />

criticism and are currently under review [60]. It is<br />

anticipated that the revised criteria will dist<strong>in</strong>guish possible/probable<br />

and def<strong>in</strong>ite bvFTD, be easier and more<br />

flexible <strong>to</strong> apply with clearer operational def<strong>in</strong>itions,<br />

and will <strong>in</strong>clude imag<strong>in</strong>g and genetic f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

Progressive Non-Fluent Aphasia (PNFA)<br />

In PNFA, the present<strong>in</strong>g features reflect the breakdown<br />

of processes vital for effortless verbal communication,<br />

center<strong>in</strong>g on Broca’s area, the anterior <strong>in</strong>sula<br />

and the perisylvian structures. While some patients<br />

have a predom<strong>in</strong>antly mo<strong>to</strong>r speech disorder (or apraxia<br />

of speech), others have ma<strong>in</strong>ly syntactic problems [61].<br />

Their speech is labored and they often stumble over<br />

certa<strong>in</strong> words, make grammatical errors, and have variable<br />

degrees of dysarthria. Word-f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g difficulty and<br />

word pauses are common, further contribut<strong>in</strong>g <strong>to</strong> reduced<br />

speech fluency. Phonemes, the most elemental<br />

components of verbal language, may be <strong>in</strong>appropriately<br />

selected or substituted, and such phonemic errors<br />

and paraphrasias are common. For example, the patient<br />

with PNFA may say “kanbaroo” rather than “kangaroo”<br />

or “wrisk” rather than “whisk”. M<strong>in</strong>or nam<strong>in</strong>g difficulties<br />

are apparent, but the severe anomia as encountered<br />

with SD is not a feature. Word repetition is typically<br />

impaired, particularly when attempt<strong>in</strong>g multisyllabic<br />

words such as “hippopotamus”, “chrysanthemum”,<br />

or “methodist episcopal” but comprehension of word<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g is preserved. Syntax (sentence construction)<br />

may be impaired and patients use simplified grammar<br />

with occasional <strong>in</strong>flectional errors and omissions, but<br />

severe agrammatism is uncommon. Although typically<br />

not reported by patients, sentence comprehension is<br />

often impaired. This is best observed when test<strong>in</strong>g sequenc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

of tasks with more complex sentence structures,<br />

for example “Touch the pen after hand<strong>in</strong>g me the<br />

razor”.<br />

Semantic Dementia (SD)<br />

Although the predom<strong>in</strong>ant features of SD are anomia<br />

and impaired word comprehension, there is breakdown<br />

of the amodal knowledge system, the hub of which is<br />

located <strong>in</strong> the anterior temporal lobe. In contrast <strong>to</strong><br />

PNFA, SD presents with progressive fluent aphasia and<br />

word comprehension deficits. Initially patients may report<br />

“loss of memory for words” or difficulty remember<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the names of people. Anomia, the <strong>in</strong>ability <strong>to</strong><br />

name objects, is an <strong>in</strong>tegral component of SD with<br />

the names of <strong>in</strong>frequently used objects usually affected<br />

first. For example, the patient may be unable <strong>to</strong> name<br />

a stethoscope but is able <strong>to</strong> name a pen. As SD progresses,<br />

the names of more common objects become<br />

difficult <strong>to</strong> produce and patients often resort <strong>to</strong> circumlocutions<br />

<strong>to</strong> express their mean<strong>in</strong>g. For example, when<br />

asked <strong>to</strong> name a can opener, a patient with SD may

J.R. Burrell and J.R. Hodges / <strong>From</strong> <strong>FUS</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Fibs</strong>: What’s <strong>New</strong> <strong>in</strong> Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia? 353<br />

say “it’s a special device for open<strong>in</strong>g cans”, rather than<br />

“a can opener”. As anomia progresses, less frequently<br />

used words are replaced by more common generalizations<br />

such as “th<strong>in</strong>g” or “stuff” and sub-category<br />

nam<strong>in</strong>g becomes more difficult. For example, breeds<br />

of dog such as “beagle”, “labrador” or “poodle” may<br />

all be referred <strong>to</strong> as “dog” and then all four-legged animals<br />

are likely <strong>to</strong> be called “dog” or “cat”. Progressive<br />

deficits <strong>in</strong> word mean<strong>in</strong>g become apparent over time<br />

and can be assessed by ask<strong>in</strong>g the patient <strong>to</strong> “repeat and<br />

def<strong>in</strong>e” a word. Patients with SD are generally able<br />

<strong>to</strong> repeat a word without difficulty, but are unable <strong>to</strong><br />

def<strong>in</strong>e it (“Hippopotamus? What is that? I’m sure I<br />

used <strong>to</strong> know”). Word comprehension difficulties are<br />

also apparent when the patient attempts <strong>to</strong> read. Patients<br />

typically show surface dyslexia, where irregular<br />

English words with specific and unpredictable pronunciation<br />

rules are <strong>in</strong>correctly read aloud [62–64]. For<br />

example, the patient with SD may pronounce the word<br />

“p<strong>in</strong>t” as though it rhymed with “m<strong>in</strong>t”. Other irregular<br />

words such as “soot”, “yacht” or “colonel” also present<br />

difficulties. Although behavioral symp<strong>to</strong>ms are not the<br />

dom<strong>in</strong>ant cl<strong>in</strong>ical feature of SD, a number of changes<br />

<strong>in</strong> personality and behavior are observed. Patients may<br />

become emotionally withdrawn, apathetic, dis<strong>in</strong>hibited,<br />

show stereotyped and rigid behaviors or develop a<br />

preference for sweet foods. Less frequently, patients<br />

with SD develop more right greater than left sided anterior<br />

temporal atrophy, and consequently display several<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>ct cl<strong>in</strong>ical features. Difficulty <strong>in</strong> recogniz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

faces, or prosapagnosia, is frequent and behavioral<br />

symp<strong>to</strong>ms are more common <strong>in</strong> right temporal SD than<br />

<strong>in</strong> classic SD [65–68].<br />

Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (LPA)<br />

Not all cases of primary progressive aphasia can be<br />

neatly classified as either PNFA or SD. In recent years,<br />

a third group of patients with progressive aphasia characterized<br />

by hesitant speech with prom<strong>in</strong>ent word f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g<br />

difficulty, anomia, <strong>in</strong>tact word but impaired sentence<br />

repetition and markedly impaired audi<strong>to</strong>ry verbal<br />

short-term memory has been described [69,70]. This<br />

syndrome, called logopenic progressive aphasia (LPA),<br />

while shar<strong>in</strong>g some cl<strong>in</strong>ical features with PNFA and<br />

SD, appears <strong>to</strong> represent an atypical variant of AD,<br />

rather than a cl<strong>in</strong>ical phenotype of FTD [71].<br />

ASSESSMENT<br />

The bedside or cl<strong>in</strong>ic cognitive assessment <strong>in</strong>volves<br />

a detailed patient and <strong>in</strong>formant <strong>in</strong>terview, simple test<strong>in</strong>g<br />

of cognitive doma<strong>in</strong>s, and a neurological exam<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

[72,73]. It is preferable <strong>to</strong> <strong>in</strong>terview the patient<br />

and <strong>in</strong>formant separately <strong>in</strong> order <strong>to</strong> confirm or<br />

elaborate on elements of the his<strong>to</strong>ry which may prove<br />

sensitive or embarrass<strong>in</strong>g. Even <strong>in</strong> advanced cases an<br />

assessment of <strong>in</strong>sight, spontaneous speech, and social<br />

<strong>in</strong>teraction can usually be attempted. As the <strong>in</strong>terview<br />

proceeds, speech fluency, word-f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g difficulties or<br />

pauses, and phonemic paraphrasias are noted. Other<br />

symp<strong>to</strong>ms such as apraxia or visuospatial disturbance<br />

should also be explored. A family his<strong>to</strong>ry of dementia,<br />

mental illness, or ALS should be sought and clarified<br />

when identified.<br />

Cognition can be assessed surpris<strong>in</strong>gly well <strong>in</strong> the<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ic or at the bedside [72,73]. Nam<strong>in</strong>g and semantic<br />

knowledge should be exam<strong>in</strong>ed us<strong>in</strong>g pictures or,<br />

even better, <strong>to</strong>y animals and household objects, but it is<br />

important <strong>to</strong> use both familiar and less familiar items.<br />

Comprehension of simple commands and grammatical<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g, often mildly abnormal <strong>in</strong> patients with<br />

PNFA, should be exam<strong>in</strong>ed with multi-step commands<br />

such as “Touch the razor and then the scissors” or “Give<br />

me the razor after you have <strong>to</strong>uched the pencil”. S<strong>in</strong>gle<br />

word repetition is often impaired <strong>in</strong> PNFA. In contrast,<br />

patients with SD are generally able <strong>to</strong> repeat but<br />

not def<strong>in</strong>e the word. Read<strong>in</strong>g aloud may reveal surface<br />

dyslexia, a feature of SD. Executive function is<br />

assessed with verbal fluency tests (letter and category),<br />

proverb <strong>in</strong>terpretation, or test<strong>in</strong>g the patient’s ability <strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>hibit alternat<strong>in</strong>g hand movements.<br />

The bedside cognitive assessment should be complemented<br />

with a neuropsychological exam<strong>in</strong>ation, which<br />

is reviewed elsewhere [73,74]. The M<strong>in</strong>i-Mental Status<br />

Exam<strong>in</strong>ation (MMSE), although commonly used <strong>in</strong><br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical practice, it is <strong>in</strong>sensitive <strong>to</strong> the cognitive deficits<br />

encountered <strong>in</strong> FTD [75]. The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive<br />

Exam<strong>in</strong>ation (ACE-R) <strong>in</strong>corporates elements of<br />

the MMSE, but <strong>in</strong>cludes a more thorough assessment of<br />

language (with fluency, nam<strong>in</strong>g, and semantic knowledge<br />

tasks), visuospatial ability, and memory, is effective<br />

<strong>in</strong> the dist<strong>in</strong>ction of FTD from AD [76,77]. The<br />

ACE-R is freely available onl<strong>in</strong>e for cl<strong>in</strong>ical use [78].<br />

Traditional neuropsychological assessments are not<br />

particularly sensitive <strong>to</strong> the deficits <strong>in</strong> social cognition<br />

encountered <strong>in</strong> patients with FTD, especially early<br />

bvFTD [79]. However, a new generation of tasks test<strong>in</strong>g<br />

complex decision mak<strong>in</strong>g [80,81],emotion process-

354 J.R. Burrell and J.R. Hodges / <strong>From</strong> <strong>FUS</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Fibs</strong>: What’s <strong>New</strong> <strong>in</strong> Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia?<br />

<strong>in</strong>g [49,82,83], sarcasm detection [49,84], and “Theory<br />

of M<strong>in</strong>d” [80,85] have been developed <strong>to</strong> address this.<br />

Similarly, new tasks have been developed <strong>to</strong> demonstrate<br />

and characterize the speech output and semantic<br />

deficits encountered <strong>in</strong> PNFA and SD [86].<br />

Physical exam<strong>in</strong>ation may be normal <strong>in</strong> patients with<br />

FTD. In some cases of bvFTD, or rarely PNFA, features<br />

of mo<strong>to</strong>r neurone dysfunction such as hyper-reflexia,<br />

muscle wast<strong>in</strong>g, weakness, fasciculations, or dysarthria<br />

may be detected [3]. Other patients, particularly those<br />

with PNFA, may demonstrate the park<strong>in</strong>sonian features<br />

of corticobasal syndrome or progressive supranuclear<br />

palsy such as rigidity, bradyk<strong>in</strong>esia, gait disturbance,<br />

and eye movement abnormalities [87–90].<br />

NEUROIMAGING<br />

Neuroimag<strong>in</strong>g has been <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly applied <strong>to</strong> the<br />

assessment of patients with FTD. Structural imag<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

most typically with magnetic resonance imag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

(MRI), reveals relatively well circumscribed, but varied,<br />

frontal and temporal lobe atrophy. The distribution<br />

of frontal and temporal atrophy observed on MRI correlates<br />

with the cl<strong>in</strong>ical phenotype [91]. In bvFTD, bilateral<br />

frontal and temporal atrophy is encountered [58],<br />

with the orbi<strong>to</strong>frontal cortex, superior frontal gyrus,<br />

temporal pole, <strong>in</strong>sula, en<strong>to</strong>rh<strong>in</strong>al cortex, hippocampus,<br />

and the head of the caudate affected [92,93]. Sophisticated<br />

MRI imag<strong>in</strong>g techniques have identified dysfunction<br />

of differ<strong>in</strong>g neural circuits <strong>in</strong> FTD phenotypes [94],<br />

and selective vulnerabilities of specific circuits may<br />

underp<strong>in</strong> the cl<strong>in</strong>ical features and distribution of neuropathologic<br />

appearance of FTD [95]. For example,<br />

selective atrophy of the anterior c<strong>in</strong>gulate cortex and<br />

anterior <strong>in</strong>sula, correspond<strong>in</strong>g with the location of von<br />

Economo neurons – a unique neuron type identified<br />

<strong>in</strong> humans and higher primates, has been identified <strong>in</strong><br />

early bvFTD us<strong>in</strong>g MR techniques [96]. The neural<br />

correlates of behavioral symp<strong>to</strong>ms have been studied<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g voxel based morphometry. For example, apathy<br />

has been associated with atrophy of right dorsolateral<br />

frontal structures, whereas dis<strong>in</strong>hibition has been<br />

associated with grey matter loss of the right temporal<br />

lobe, particularly of the amygdala and hippocampus<br />

[97]. White matter changes on diffusion tensor<br />

imag<strong>in</strong>g (DTI) have also been correlated with symp<strong>to</strong>ms<br />

<strong>in</strong> bvFTD. For example, the superior longitud<strong>in</strong>al<br />

fasciculus has been l<strong>in</strong>ked with behavioral symp<strong>to</strong>ms<br />

<strong>in</strong> bvFTD [98].<br />

In PNFA, atrophy is most marked <strong>in</strong> the left superior<br />

temporal and <strong>in</strong>ferior frontal lobes, as well as<br />

the left <strong>in</strong>sula [17,99,100]. SD is characterized by<br />

asymmetrical temporal lobe atrophy (worse on the left<br />

than the right) with atrophy of the perirh<strong>in</strong>al cortex,<br />

as well as the parahippocampal, fusiform, and <strong>in</strong>ferior<br />

temporal gyri [17,99]. Functional imag<strong>in</strong>g with<br />

F 18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission <strong>to</strong>mography<br />

(FDG-PET) <strong>in</strong> FTD reveals frontal and temporal hypometabolism,<br />

and FDG-PET is a useful adjunct <strong>in</strong> the<br />

dist<strong>in</strong>ction of FTD from other dementias [101–103].<br />

Recently, the use of carbon 11-labeled Pittsburgh compound<br />

B positron emission <strong>to</strong>mography (PiB-PET) has<br />

been used <strong>to</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>guish atypical presentations of AD<br />

from FTD [99]. Patients with AD pathology demonstrate<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased PiB b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g, but patients with FTD do<br />

not [71,104,105]. Positron emission <strong>to</strong>mography ligands<br />

<strong>to</strong> detect tau, TDP-43, or <strong>FUS</strong> pathology are not<br />

currently available.<br />

TREATMENT<br />

Currently there are no disease specific treatment <strong>in</strong>terventions<br />

for FTD. Consequently, treatment largely<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>s supportive and <strong>in</strong>volves a comb<strong>in</strong>ation of<br />

non-pharmacological and pharmacological measures,<br />

aimed at reduc<strong>in</strong>g the effect of troublesome behaviors<br />

[106]. The impact of FTD on family members is<br />

enormous with high levels of stress and burden [107,<br />

108]. Carer education and support are essential and<br />

have been enhanced by the publication of a free booklet,<br />

“Understand<strong>in</strong>g Younger Onset Dementia” [78].<br />

The role of pharmacological <strong>in</strong>terventions <strong>in</strong> FTD rema<strong>in</strong>s<br />

uncerta<strong>in</strong>, and only small and often conflict<strong>in</strong>g<br />

treatment trials have been conducted thus far. Selective<br />

sero<strong>to</strong>n<strong>in</strong> reuptake <strong>in</strong>hibi<strong>to</strong>rs (SSRIs) such as paroxet<strong>in</strong>e<br />

have been used <strong>to</strong> treat dis<strong>in</strong>hibition and challeng<strong>in</strong>g<br />

behaviors, but evidence for their use rema<strong>in</strong>s contradic<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

[109,110]. Atypical antipsychotics such as<br />

olanzep<strong>in</strong>e have been used for behaviors unresponsive<br />

<strong>to</strong> SSRIs or <strong>in</strong> patients with prom<strong>in</strong>ent delusions [111].<br />

Antichol<strong>in</strong>esterase <strong>in</strong>hibi<strong>to</strong>rs, the ma<strong>in</strong>stay of AD therapy,<br />

do not have an established role <strong>in</strong> the treatment of<br />

FTD. One study reported improvement <strong>in</strong> measures of<br />

behavioral disturbance and carer stress with rivastigm<strong>in</strong>e<br />

[112], however, deterioration <strong>in</strong> neuropsychiatric<br />

symp<strong>to</strong>ms without cognitive improvement was demonstrated<br />

with donepezil [113].

J.R. Burrell and J.R. Hodges / <strong>From</strong> <strong>FUS</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Fibs</strong>: What’s <strong>New</strong> <strong>in</strong> Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia? 355<br />

Table 1<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong>ical features of FTD phenotypes<br />

Characteristic Behavioral FTD (bvFTD) Progressive Non-Fluent Aphasia<br />

(PNFA)<br />

Heritability ++ + +/-<br />

Behavior – Severe Apathy<br />

– Dis<strong>in</strong>hibition<br />

– Reduced empathy<br />

– Stereotyped behavior and perseveration<br />

– Changed food preference,<br />

weight ga<strong>in</strong><br />

– Literal proverb <strong>in</strong>terpretation<br />

– Mental rigidity<br />

– Executive dysfunction<br />

– Relatively preserved <strong>in</strong> early<br />

stages<br />

Language – Adynamism – Non-Fluent speech<br />

– Hesitancy<br />

– Apraxia of Speech<br />

– Phoenemic errors<br />

– Syntactic errors<br />

– Mild anomia<br />

– Impaired s<strong>in</strong>gle word and sentence<br />

repetition<br />

MRI features – Frontal atrophy<br />

– Orbi<strong>to</strong>mesial<br />

– Temporal atrophy<br />

– Temporal pole<br />

– Hippocampus<br />

– Amygdala<br />

– Caudate (head)<br />

– Severe left temporal atrophy ∗<br />

– Perisylvian<br />

% Tau positive cases < 50% 70% < 10%<br />

% TDP-43 cases < 50% 30% > 90%<br />

% <strong>FUS</strong> positive cases 5–10% Unknown Unknown<br />

∗ Features of the right temporal variant of SD.<br />

OUTSTANDING ISSUES<br />

Although disease specific treatments for FTD are not<br />

available, the development of anti-tau therapies <strong>in</strong> the<br />

context of AD holds promise for future FTD therapeutics<br />

[114]. Should specific anti-tau or anti-TDP-43<br />

therapies be developed, the ability <strong>to</strong> predict underly<strong>in</strong>g<br />

neuropathologic processes at an early stage will become<br />

crucial [115]. Careful ref<strong>in</strong>ement of FTD phenotypes<br />

is one attempt <strong>to</strong> achieve this. For <strong>in</strong>stance,<br />

it is clear that SD is associated with TDP-43 pathology<br />

[116] but has very low heritability and gene mutations<br />

are consequently rare [32]. PNFA, by contrast,<br />

appears <strong>to</strong> be more commonly associated with<br />

tau pathology, especially when apraxia of speech is<br />

present [117]. Sensitive and specific biomarkers are<br />

clearly needed. CSF biomarkers such as <strong>to</strong>tal tau and<br />

ratios of tau <strong>to</strong> amyloid-β42 have been demonstrated <strong>to</strong><br />

dist<strong>in</strong>guish FTD from AD <strong>in</strong> vivo [118,119], but their<br />

utility <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual cases is unproven. Serum TDP-<br />

Semantic Dementia (SD)<br />

– Preference for sweet foods, (late)<br />

– Apathy (late)*<br />

– Dis<strong>in</strong>hibition (late)*<br />

– Impaired facial recognition*<br />

– Fluent speech<br />

– Severe anomia<br />

– Circumlocutions <strong>to</strong> express mean<strong>in</strong>g<br />

– Surface dyslexia<br />

– Normal word and sentence repetition<br />

– Bilateral anterior temporal atrophy<br />

(usually left > right)<br />

– Perirh<strong>in</strong>al cortex<br />

– Fusiform gyrus<br />

– Inferior temporal gyrus<br />

43 has also been studied as a potential biomarker for<br />

FTD and ALS [120–122]. Serum progranul<strong>in</strong> levels,<br />

which are low <strong>in</strong> patients with PGRN mutations [123],<br />

may provide a useful screen<strong>in</strong>g test for these mutations.<br />

PET and MRI imag<strong>in</strong>g may support the cl<strong>in</strong>ical<br />

diagnosis of FTD, <strong>to</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>guish FTD from AD<br />

and <strong>to</strong> aid FTD phenotype classification [99,102,124,<br />

125]. Accurate prediction of underly<strong>in</strong>g pathology is<br />

likely <strong>to</strong> require a comb<strong>in</strong>ed approach us<strong>in</strong>g a range of<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigative techniques.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

Developments <strong>in</strong> the field of FTD are proceed<strong>in</strong>g<br />

rapidly. Consequently, efforts <strong>to</strong> revise the diagnostic<br />

criteria, tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><strong>to</strong> account cl<strong>in</strong>ical features, genetic,<br />

imag<strong>in</strong>g, and pathologic characteristics are underway.<br />

The revised criteria will hopefully allow the dist<strong>in</strong>ction<br />

of “phenocopy” FTD patients from those with progres-

356 J.R. Burrell and J.R. Hodges / <strong>From</strong> <strong>FUS</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Fibs</strong>: What’s <strong>New</strong> <strong>in</strong> Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia?<br />

sive dementia. The shared cl<strong>in</strong>ical, genetic, and pathological<br />

features of FTD and ALS have provided new<br />

<strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong><strong>to</strong> both disorders which <strong>to</strong>gether form a s<strong>in</strong>gle<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>icopathological spectrum. Although tau positive<br />

<strong>in</strong>traneuronal <strong>in</strong>clusions were identified <strong>in</strong>itially,<br />

TDP-43 positive <strong>in</strong>clusions are now recognized as the<br />

most frequent underly<strong>in</strong>g his<strong>to</strong>pathology <strong>in</strong> FTD and<br />

ALS. The observed familial clusters of FTD and ALS<br />

have not yet been def<strong>in</strong>itively expla<strong>in</strong>ed. Furthermore,<br />

the <strong>in</strong>cidence of subcl<strong>in</strong>ical mo<strong>to</strong>r dysfunction <strong>in</strong> FTD,<br />

or cognitive symp<strong>to</strong>ms <strong>in</strong> ALS, has not yet been def<strong>in</strong>itively<br />

established and is the subject of further study.<br />

The comb<strong>in</strong>ation of FTD and ALS is associated with<br />

a poorer prognosis, but whether the prognosis of TDP-<br />

43 positive cases differs significantly from tau positive<br />

FTD cases rema<strong>in</strong>s controversial. Moreover, the role<br />

of neuropsychologic exam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> the assessment of<br />

ALS patients is yet <strong>to</strong> be established. The need for<br />

suitable biomarkers <strong>in</strong> life of dist<strong>in</strong>ctive pathological<br />

entities, and their relationship <strong>to</strong> prognosis, is clear and<br />

will be necessary for the future development of disease<br />

specific treatments.<br />

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

Dr. James R. Burrell gratefully acknowledges the<br />

support of the National Health and Medical Research<br />

Council of Australia and the Mo<strong>to</strong>r Neurone Disease<br />

Research Institute of Australia.<br />

Professor John R. Hodges is <strong>in</strong> receipt of an Australian<br />

Research Council Federation Fellowship Grant.<br />

Authors’ dislcosures available onl<strong>in</strong>e (http://www.jalz.com/disclosures/view.php?id=317).<br />

REFERENCES<br />

[1] Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, Hodges JR (2002) The<br />

prevalence of fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia. Neurology 58, 1615-<br />

1621.<br />

[2] Rosso SM, Kaat LD, Baks T, Joosse M, de Kon<strong>in</strong>g I, Pijnenburg<br />

Y, de Jong D, Dooijes D, Kamphorst W, Ravid R,<br />

Niermeijer MF, Verheij F, Kremer HP, Scheltens P, van Duijn<br />

CM, Heut<strong>in</strong>k P, van Swieten JC (2003) Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia<br />

<strong>in</strong> The Netherlands: patient characteristics and prevalence<br />

estimates from a population-based study. Bra<strong>in</strong> 126,<br />

2016-2022.<br />

[3] Lomen-Hoerth C, Anderson T, Miller B (2002) The overlap<br />

of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia.<br />

Neurology 59, 1077-9.<br />

[4] Cairns N, Bigio E, Mackenzie I, Neumann M, Lee V, Hatanpaa<br />

K, White C, Schneider J, Gr<strong>in</strong>berg L, Halliday G, Duyckaerts<br />

C, Lowe J, Holm I, Tolnay M, Okamo<strong>to</strong> K, Yokoo<br />

H, Murayama S, Woulfe J, Muñoz D, Dickson D, Ince P,<br />

Trojanowski J, Mann D (2007) Neuropathologic diagnostic<br />

and nosologic criteria for fron<strong>to</strong>temporal lobar degeneration:<br />

consensus of the Consortium for Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Lobar Degeneration.<br />

Acta Neuropathol 114, 5-22.<br />

[5] Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi<br />

MC, Chou TT, Bruce J, Schuck T, Grossman M, Clark<br />

CM, McCluskey LF, Miller BL, Masliah E, Mackenzie IR,<br />

Feldman H, Feiden W, Kretzschmar HA, Trojanowski JQ,<br />

Lee VM (2006) Ubiquit<strong>in</strong>ated TDP-43 <strong>in</strong> fron<strong>to</strong>temporal lobar<br />

degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science<br />

314, 130-133.<br />

[6] Neumann M, Rademakers R, Roeber S, Baker M, Kretzschmar<br />

HA, Mackenzie IRA (2009) A new subtype of fron<strong>to</strong>temporal<br />

lobar degeneration with <strong>FUS</strong> pathology. Bra<strong>in</strong><br />

132, 2922-2931.<br />

[7] Taniguchi S, McDonagh AM, Picker<strong>in</strong>g-Brown SM, Umeda<br />

Y, Iwatsubo T, Hasegawa M, Mann DMA (2004) The neuropathology<br />

of fron<strong>to</strong>temporal lobar degeneration with respect<br />

<strong>to</strong> the cy<strong>to</strong>logical and biochemical characteristics of<br />

tau prote<strong>in</strong>. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 30, 1-18.<br />

[8] Mott RT, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, Zhukareva V, Lee<br />

VM, Forman M, Van Deerl<strong>in</strong> V, Erv<strong>in</strong> JF, Wang D, Schmechel<br />

DE, Hulette CM (2005) Neuropathologic, biochemical, and<br />

molecular characterization of the fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementias.<br />

J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 64, 420-428.<br />

[9] Geser F, Mart<strong>in</strong>ez-Lage M, Rob<strong>in</strong>son J, Uryu K, Neumann<br />

M, Brandmeir NJ, Xie SX, Kwong LK, Elman L, McCluskey<br />

L, Clark CM, Malunda J, Miller BL, Zimmerman EA, Qian<br />

J, Van Deerl<strong>in</strong> V, Grossman M, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ<br />

(2009) Cl<strong>in</strong>ical and Pathological Cont<strong>in</strong>uum of Multisystem<br />

TDP-43 Prote<strong>in</strong>opathies. Arch Neurol 66, 180-189.<br />

[10] Mackenzie IRA, Foti D, Woulfe J, Hurwitz TA (2008)<br />

Atypical fron<strong>to</strong>temporal lobar degeneration with ubiquit<strong>in</strong>positive,<br />

TDP-43-negative neuronal <strong>in</strong>clusions. Bra<strong>in</strong> 131,<br />

1282-1293.<br />

[11] Mendez MF, Selwood A, Mastri AR, Frey WH (1993) Pick’s<br />

disease versus Alzheimer’s disease: A comparison of cl<strong>in</strong>ical<br />

characteristics. Neurology 43, 289-292.<br />

[12] Varma AR, Snowden JS, Lloyd JJ, Talbot PR, Mann DMA,<br />

Neary D (1999) Evaluation of the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria<br />

<strong>in</strong> the differentiation of Alzheimer’s disease and fron<strong>to</strong>temporal<br />

dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 66, 184-188.<br />

[13] Hodges JR, Davies R, Xuereb J, Kril J, Halliday G (2003)<br />

Survival <strong>in</strong> fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia. Neurology 61, 349-54.<br />

[14] Roberson ED, Hesse JH, Rose KD, Slama H, Johnson JK,<br />

Yaffe K, Forman MS, Miller CA, Trojanowski JQ, Kramer<br />

JH, Miller BL (2005) Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia progresses <strong>to</strong><br />

death faster than Alzheimer disease. Neurology 65, 719-725.<br />

[15] Snowden J, Neary D, Mann D (2007) Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal lobar<br />

degeneration: cl<strong>in</strong>ical and pathological relationships. Acta<br />

Neuropathol 114, 31-38.<br />

[16] Hodges JR Patterson K (2007) Semantic dementia: a unique<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>icopathological syndrome. Lancet Neurol 6, 1004-1014.<br />

[17] Rohrer JD, Warren JD, Modat M, Ridgway GR, Douiri A,<br />

Rossor MN, Oursel<strong>in</strong> S, Fox NC (2009) Patterns of cortical<br />

th<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the language variants of fron<strong>to</strong>temporal lobar<br />

degeneration. Neurology 72, 1562-1569.<br />

[18] Josephs KA, Hol<strong>to</strong>n JL, Rossor MN, Godbolt AK, Ozawa T,<br />

Strand K, Khan N, Al-Sarraj S, Revesz T (2004) Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal<br />

lobar degeneration and ubiquit<strong>in</strong> immunohis<strong>to</strong>chemistry.<br />

Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 30, 369-373.<br />

[19] Neumann M, Tolnay M, Mackenzie IR (2009) The Molecular<br />

Basis of Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia. Expert Rev Mol Med 11,<br />

e23.

J.R. Burrell and J.R. Hodges / <strong>From</strong> <strong>FUS</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Fibs</strong>: What’s <strong>New</strong> <strong>in</strong> Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia? 357<br />

[20] Belzil VV, Valdmanis PN, Dion PA, Daoud H, Kabashi E,<br />

Noreau A, Gauthier J, for the S2D team, H<strong>in</strong>ce P, Desjarlais<br />

A, Bouchard J-, Lacomblez L, Salachas F, Pradat P-, Camu<br />

W, Me<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ger V, Dupre N, Rouleau GA (2009) Mutations <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>FUS</strong> cause FALS and SALS <strong>in</strong> French and French Canadian<br />

populations. Neurology 73, 1176-1179.<br />

[21] Ticozzi N, Silani V, LeClerc AL, Keagle P, Gellera C, Ratti<br />

A, Taroni F, Kwiatkowski TJ, McKenna-Yasek DM, Sapp<br />

PC, Brown RH, Landers JE (2009) Analysis of <strong>FUS</strong> gene<br />

mutation <strong>in</strong> familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with<strong>in</strong> an<br />

Italian cohort. Neurology 73, 1180-1185.<br />

[22] Kwiatkowski TJ, Bosco DA, LeClerc AL, Tamrazian E, Vanderburg<br />

CR, Russ C, Davis A, Gilchrist J, Kasarskis EJ,<br />

Munsat T, Valdmanis P, Rouleau GA, Hosler BA, Cortelli<br />

P, de Jong PJ, Yosh<strong>in</strong>aga Y, Ha<strong>in</strong>es JL, Pericak-Vance MA,<br />

Yan J, Ticozzi N, Siddique T, McKenna-Yasek D, Sapp PC,<br />

Horvitz HR, Landers JE, Brown RH (2009) Mutations <strong>in</strong><br />

the <strong>FUS</strong>/TLS gene on chromosome 16 cause familial amyotrophic<br />

lateral sclerosis. Science 323, 1205-1208.<br />

[23] Vance C, Rogelj B, Hor<strong>to</strong>bágyi T, De Vos KJ, Nishimura AL,<br />

Sreedharan J, Hu X, Smith B, Ruddy D, Wright P, Ganesal<strong>in</strong>gam<br />

J, Williams KL, Tripathi V, Al-Saraj S, Al-Chalabi<br />

A, Leigh PN, Blair IP, Nicholson G, de Belleroche J, Gallo J,<br />

Miller CC, Shaw CE (2009) Mutations <strong>in</strong> <strong>FUS</strong>, an RNA process<strong>in</strong>g<br />

prote<strong>in</strong>, cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis<br />

type 6. Science 323, 1208-1211.<br />

[24] Blair IP, Williams KL, Warraich ST, Durnall JC, Thoeng AD,<br />

Manavis J, Blumbergs PC, Vucic S, Kiernan MC, Nicholson<br />

GA (2009) <strong>FUS</strong> mutations <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic lateral sclerosis:<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical, pathological, neurophysiological and genetic<br />

analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, <strong>in</strong> press.<br />

[25] Lagier-Tourenne C Cleveland DW (2009) Reth<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g ALS:<br />

The <strong>FUS</strong> about TDP-43. Cell 136, 1001-1004.<br />

[26] Shi J, Shaw C, Plessis D, Richardson A, Bailey K, Julien<br />

C, S<strong>to</strong>pford C, Thompson J, Varma A, Craufurd D, Tian J,<br />

Picker<strong>in</strong>g-Brown S, Neary D, Snowden J, Mann D (2005)<br />

His<strong>to</strong>pathological changes underly<strong>in</strong>g fron<strong>to</strong>temporal lobar<br />

degeneration with cl<strong>in</strong>icopathological correlation. Acta Neuropathol<br />

110, 501-512.<br />

[27] Hodges JR, Davies RR, Xuereb JH, Casey B, Broe M, Bak<br />

TH, Kril JJ, Halliday GM (2004) Cl<strong>in</strong>icopathological correlates<br />

<strong>in</strong> fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia. Ann Neurol 56, 399-406.<br />

[28] Lladó A, Sánchez-Valle R, Rey MJ, Ezquerra M, Tolosa<br />

E, Ferrer I, Mol<strong>in</strong>uevo JL (2008) Cl<strong>in</strong>icopathological and<br />

genetic correlates of fron<strong>to</strong>temporal lobar degeneration and<br />

corticobasal degeneration. J Neurol 255, 488-494.<br />

[29] Seelaar H, Klijnsma K, de Kon<strong>in</strong>g I, van der Lugt A, Chiu W,<br />

Azmani A, Rozemuller A, van Swieten J (2010) Frequency<br />

of ubiquit<strong>in</strong> and <strong>FUS</strong>-positive, TDP-43-negative fron<strong>to</strong>temporal<br />

lobar degeneration. J Neurol 257, 747-753.<br />

[30] Rosso SM, Kaat LD, Baks T, Joosse M, de Kon<strong>in</strong>g I, Pijnenburg<br />

Y, de Jong D, Dooijes D, Kamphorst W, Ravid R,<br />

Niermeijer MF, Verheij F, Kremer HP, Scheltens P, van Duijn<br />

CM, Heut<strong>in</strong>k P, van Swieten JC (2003) Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia<br />

<strong>in</strong> The Netherlands: patient characteristics and prevalence<br />

estimates from a population-based study. Bra<strong>in</strong> 126,<br />

2016-2022.<br />

[31] Stevens M, van Duijn C, Kamphorst W, de Knijff P, Heut<strong>in</strong>k<br />

P, van Gool W, Scheltens P, Ravid R, Oostra B, Niermeijer M,<br />

van Swieten J (1998) Familial aggregation <strong>in</strong> fron<strong>to</strong>temporal<br />

dementia. Neurology 50, 1541-1545.<br />

[32] Rohrer JD, Guerreiro R, Vandrovcova J, Uphill J, Reiman D,<br />

Beck J, Isaacs AM, Authier A, Ferrari R, Fox NC, Mackenzie<br />

I, Warren JD, de Silva R, Hol<strong>to</strong>n J, Revesz T, Hardy J, Mead<br />

S, Rossor MN (2009) The heritability and genetics of fron<strong>to</strong>temporal<br />

lobar degeneration. Neurology 73, 1451-1456.<br />

[33] Seelaar H, Kamphorst W, Rosso SM, Azmani A, Masdjedi<br />

R, de Kon<strong>in</strong>g I, Maat-Kievit JA, Anar B, Kaat LD, Breedveld<br />

GJ, Dooijes D, Rozemuller JM, Bronner IF, Rizzu P, van<br />

Swieten JC (2008) Dist<strong>in</strong>ct genetic forms of fron<strong>to</strong>temporal<br />

dementia. Neurology 71, 1220-1226.<br />

[34] Poorkaj P, Grossman M, Ste<strong>in</strong>bart E, Payami H, Sadovnick A,<br />

Nochl<strong>in</strong> D, Tabira T, Trojanowski JQ, Borson S, Galasko D,<br />

Reich S, Qu<strong>in</strong>n B, Schellenberg G, Bird TD (2001) Frequency<br />

of Tau Gene Mutations <strong>in</strong> Familial and Sporadic Cases of<br />

Non-Alzheimer Dementia. Arch Neurol 58, 383-387.<br />

[35] Gass J, Cannon A, Mackenzie IR, Boeve B, Baker M, Adamson<br />

J, Crook R, Melquist S, Kuntz K, Petersen R, Josephs<br />

K, Picker<strong>in</strong>g-Brown SM, Graff-Radford N, Uitti R, Dickson<br />

D, Wszolek Z, Gonzalez J, Beach TG, Bigio E, Johnson N,<br />

We<strong>in</strong>traub S, Mesulam M, White CL, Woodruff B, Caselli<br />

R, Hsiung G, Feldman H, Knopman D, Hut<strong>to</strong>n M, Rademakers<br />

R (2006) Mutations <strong>in</strong> progranul<strong>in</strong> are a major cause of<br />

ubiquit<strong>in</strong>-positive fron<strong>to</strong>temporal lobar degeneration. Hum<br />

Mol Genet 15, 2988-3001.<br />

[36] Schymick JC, Yang Y, Andersen PM, Vonsattel JP, Greenway<br />

M, Momeni P, Elder J, Chiò A, Restagno G, Robberecht<br />

W, Dahlberg C, Mukherjee O, Goate A, Graff-Radford N,<br />

Caselli RJ, Hut<strong>to</strong>n M, Gass J, Cannon A, Rademakers R,<br />

S<strong>in</strong>gle<strong>to</strong>n AB, Hardiman O, Rothste<strong>in</strong> J, Hardy J, Traynor BJ<br />

(2007) Progranul<strong>in</strong> mutations and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis<br />

or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia<br />

phenotypes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78, 754-756.<br />

[37] Benajiba L, Le Ber I, Camuzat A, Lacoste M, Thomas-<br />

Anterion C, Couratier P, Legallic S, Salachas F, Hannequ<strong>in</strong><br />

D, Decousus M, Lacomblez L, Guedj E, Golfier V, Camu<br />

W, Dubois B, Campion D, Me<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ger V, Brice A (2009)<br />

TARDBP mutations <strong>in</strong> mo<strong>to</strong>neuron disease with fron<strong>to</strong>temporal<br />

lobar degeneration. Ann Neurol 65, 470-473.<br />

[38] Borroni B, Bonvic<strong>in</strong>i C, Alberici A, Buratti E, Agosti C,<br />

Archetti S, Papetti A, Stuani C, Di Luca M, Gennarelli M,<br />

Padovani A (2009) Mutation with<strong>in</strong> TARDBP leads <strong>to</strong> fron<strong>to</strong>temporal<br />

dementia without mo<strong>to</strong>r neuron disease. Hum<br />

Mutat 30, E974-983.<br />

[39] Watts GDJ, Wymer J, Kovach MJ, Mehta SG, Mumm S,<br />

Darvish D, Pestronk A, Whyte MP, Kimonis VE (2004) Inclusion<br />

body myopathy associated with Paget disease of bone<br />

and fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia is caused by mutant valos<strong>in</strong>conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

prote<strong>in</strong>. Nat Genet 36, 377-381.<br />

[40] Park<strong>in</strong>son N, Ince PG, Smith MO, Highley R, Skib<strong>in</strong>ski G,<br />

Andersen PM, Morrison KE, Pall HS, Hardiman O, Coll<strong>in</strong>ge<br />

J, Shaw PJ, Fisher EC, on behalf of the MRC Proteomics<br />

<strong>in</strong> ALS Study and the FReJA Consortium (2006) ALS phenotypes<br />

with mutations <strong>in</strong> CHMP2B (charged multivesicular<br />

body prote<strong>in</strong> 2B). Neurology 67, 1074-1077.<br />

[41] Hosler BA, Siddique T, Sapp PC, Sailor W, Huang MC, Hossa<strong>in</strong><br />

A, Daube JR, Nance M, Fan C, Kaplan J, Hung W,<br />

McKenna-Yasek D, Ha<strong>in</strong>es JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Horvitz<br />

HR, Brown RH (2000) L<strong>in</strong>kage of Familial Amyotrophic<br />

Lateral Sclerosis With Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia <strong>to</strong> Chromosome<br />

9q21–q22. JAMA 284, 1664-1669.<br />

[42] Morita M, Al-Chalabi A, Andersen PM, Hosler B, Sapp P,<br />

Englund E, Mitchell JE, Habgood JJ, de Belleroche J, Xi J,<br />

Jongjaroenprasert W, Horvitz HR, Gunnarsson L-, Brown RH<br />

(2006) A locus on chromosome 9p confers susceptibility <strong>to</strong><br />

ALS and fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia. Neurology 66, 839-844.<br />

[43] Vance C, Al-Chalabi A, Ruddy D, Smith BN, Hu X, Sreedharan<br />

J, Siddique T, Schelhaas HJ, Kusters B, Troost D, Baas

358 J.R. Burrell and J.R. Hodges / <strong>From</strong> <strong>FUS</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Fibs</strong>: What’s <strong>New</strong> <strong>in</strong> Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia?<br />

F, de Jong V, Shaw CE (2006) Familial amyotrophic lateral<br />

sclerosis with fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia is l<strong>in</strong>ked <strong>to</strong> a locus<br />

on chromosome 9p13.2–21.3. Bra<strong>in</strong> 129, 868-876.<br />

[44] Le Ber I, Camuzat A, Berger E, Hannequ<strong>in</strong> D, Laquerriere<br />

A, Golfier V, Seilhean D, Viennet G, Couratier P, Verpillat P,<br />

Heath S, Camu W, Mart<strong>in</strong>aud O, Lacomblez L, Vercellet<strong>to</strong><br />

M, Salachas F, Sellal F, Didic M, Thomas-Anterion C, Puel<br />

M, Michel B, Besse C, Duyckaerts C, Me<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ger V, Campion<br />

D, Dubois B, Brice A, For the French Research Network<br />

on FTD/FTD-MND (2009) Chromosome 9p-l<strong>in</strong>ked families<br />

with fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia associated with mo<strong>to</strong>r neuron<br />

disease. Neurology 72, 1669-1676.<br />

[45] Johnson JK, Diehl J, Mendez MF, Neuhaus J, Shapira JS,<br />

Forman M, Chute DJ, Roberson ED, Pace-Savitsky C, Neumann<br />

M, Chow TW, Rosen HJ, Förstl H, Kurz A, Miller BL<br />

(2005) Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Lobar Degeneration: Demographic<br />

Characteristics of 353 Patients. Arch Neurol 62, 925-930.<br />

[46] Kipps CM, Mioshi E, Hodges JR (2009) Emotion, social<br />

function<strong>in</strong>g and activities of daily liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> fron<strong>to</strong>temporal<br />

dementia. Neurocase 15, 182-189.<br />

[47] Zamboni G, Huey ED, Krueger F, Nichelli PF, Grafman J<br />

(2008) Apathy and dis<strong>in</strong>hibition <strong>in</strong> fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia:<br />

Insights <strong>in</strong><strong>to</strong> their neural correlates. Neurology 71, 736-742.<br />

[48] Huey ED, Goveia EN, Paviol S, Pard<strong>in</strong>i M, Krueger F, Zamboni<br />

G, Tierney MC, Wassermann EM, Grafman J (2009)<br />

Executive dysfunction <strong>in</strong> fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia and corticobasal<br />

syndrome. Neurology 72, 453-459.<br />

[49] Kipps CM, Nes<strong>to</strong>r PJ, Acosta-Cabronero J, Arnold R, Hodges<br />

JR (2009) Understand<strong>in</strong>g social dysfunction <strong>in</strong> the behavioural<br />

variant of fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia: the role of<br />

emotion and sarcasm process<strong>in</strong>g. Bra<strong>in</strong> 132(Pt3), 592-603.<br />

[50] Gustafson L (1987) Frontal lobe degeneration of non-<br />

Alzheimer type. II. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical picture and differential diagnosis.<br />

Arch Geron<strong>to</strong>l Geriatr 6, 209-223.<br />

[51] Pasquier F, Lebert F, Lavenu I, Guillaume B (1999) The<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical picture of fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia: diagnosis and<br />

follow-up. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 10(Suppl 1), 10-14.<br />

[52] Mendez MF, Shapira JS, Woods RJ, Licht EA, Saul RE<br />

(2008) Psychotic symp<strong>to</strong>ms <strong>in</strong> fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia:<br />

prevalence and review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 25, 206-<br />

211.<br />

[53] Lillo, P, Garc<strong>in</strong>, B, Bak TH, Hornberger M, Hodges JR (2010)<br />

Neurobehavioral features <strong>in</strong> fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia with<br />

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol 67, 826-830.<br />

[54] Claassen DO, Parisi JE, Giann<strong>in</strong>i C, Boeve BF, Dickson<br />

DW, Josephs KA (2008) Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia Mimick<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Dementia With Lewy Bodies. Cogn Behav Neurol 21,<br />

157-163.<br />

[55] Kipps CM, Nes<strong>to</strong>r PJ, Fryer TD, Hodges JR (2007) Behavioural<br />

variant fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia: not all it seems?<br />

Neurocase 13, 237-247.<br />

[56] Davies RR, Kipps CM, Mitchell J, Kril JJ, Halliday GM,<br />

Hodges JR (2006) Progression <strong>in</strong> fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia:<br />

identify<strong>in</strong>g a benign behavioral variant by magnetic resonance<br />

imag<strong>in</strong>g. Arch Neurol 63, 1627-1631.<br />

[57] Hornberger M, Shelley BP, Kipps CM, Piguet O, Hodges<br />

JR (2009) Can progressive and non-progressive behavioural<br />

variant fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia be dist<strong>in</strong>guished at presentation?<br />

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80, 591-593.<br />

[58] Kipps CM, Hodges JR, Fryer TD, Nes<strong>to</strong>r PJ (2009) Comb<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

magnetic resonance imag<strong>in</strong>g and positron emission <strong>to</strong>mography<br />

bra<strong>in</strong> imag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> behavioural variant fron<strong>to</strong>temporal<br />

degeneration: ref<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the cl<strong>in</strong>ical phenotype. Bra<strong>in</strong> 132,<br />

2566-2578.<br />

[59] Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D,<br />

Black S, Freedman M, Kertesz A, Robert PH, Albert M,<br />

Boone K, Miller BL, Cumm<strong>in</strong>gs J, Benson DF (1998) Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal<br />

lobar degeneration: A consensus on cl<strong>in</strong>ical diagnostic<br />

criteria. Neurology 51, 1546-1554.<br />

[60] Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Kipps CM, Johnson JK, Seeley<br />

WW, Mendez MF, Knopman D, Kertesz A, Mesulam M,<br />

Salmon DP, Galasko D, Chow TW, DeCarli C, Hillis A,<br />

Josephs K, Kramer JH, We<strong>in</strong>traub S, Grossman M, Gorno-<br />

Temp<strong>in</strong>i M, Miller BM (2007) Diagnostic criteria for the behavioral<br />

variant of fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia (bvFTD): current<br />

limitations and future directions. Alzheimer Dis Assoc<br />

Disord 21, S14-18.<br />

[61] Knibb JA, Woollams AM, Hodges JR, Patterson K (2009)<br />

Mak<strong>in</strong>g sense of progressive non-fluent aphasia: an analysis<br />

of conversational speech. Bra<strong>in</strong> 132, 2734-2746.<br />

[62] Hodges J, Patterson K, Oxbury S, Funnell E (1992) Semantic<br />

dementia. Progressive fluent aphasia with temporal lobe<br />

atrophy. Bra<strong>in</strong> 115, 1783-1806.<br />

[63] Wilson SM, Brambati SM, Henry RG, Handwerker DA,<br />

Agosta F, Miller BL, Wilk<strong>in</strong>s DP, Ogar JM, Gorno-Temp<strong>in</strong>i<br />

ML (2009) The neural basis of surface dyslexia <strong>in</strong> semantic<br />

dementia. Bra<strong>in</strong> 132, 71-86.<br />

[64] Brambati SM, Ogar J, Neuhaus J, Miller BL, Gorno-Temp<strong>in</strong>i<br />

ML (2009) Read<strong>in</strong>g disorders <strong>in</strong> primary progressive aphasia:<br />

a behavioral and neuroimag<strong>in</strong>g study. Neuropsychologia 47,<br />

1893-1900.<br />

[65] Thompson SA, Patterson K, Hodges JR (2003) Left/right<br />

asymmetry of atrophy <strong>in</strong> semantic dementia: Behavioralcognitive<br />

implications. Neurology 61, 1196-1203.<br />

[66] Chan D, Anderson V, Pijnenburg Y, Whitwell J, Barnes J,<br />

Scahill R, Stevens JM, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, Rossor MN,<br />

Fox NC (2009) The cl<strong>in</strong>ical profile of right temporal lobe<br />

atrophy. Bra<strong>in</strong> 132, 1287-1298.<br />

[67] Seeley WW, Bauer AM, Miller BL, Gorno-Temp<strong>in</strong>i ML,<br />

Kramer JH, We<strong>in</strong>er M, Rosen HJ (2005) The natural his<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

of temporal variant fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia. Neurology 64,<br />

1384-1390.<br />

[68] Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Vemuri<br />

P, Senjem ML, Parisi JE, Ivnik RJ, Dickson DW, Petersen<br />

RC, Jack CR (2009) Two dist<strong>in</strong>ct subtypes of right temporal<br />

variant fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia. Neurology 73, 1443-1450.<br />

[69] Gorno-Temp<strong>in</strong>i ML, Brambati SM, G<strong>in</strong>ex V, Ogar J,<br />

Dronkers NF, Marcone A, Perani D, Garibot<strong>to</strong> V, Cappa SF,<br />

Miller BL (2008) The logopenic/phonological variant of primary<br />

progressive aphasia. Neurology 71, 1227-1234.<br />

[70] Gorno-Temp<strong>in</strong>i ML, Dronkers NF, Rank<strong>in</strong> KP, Ogar JM,<br />

Phengrasamy L, Rosen HJ, Johnson JK, We<strong>in</strong>er MW, Miller<br />

BL (2004) Cognition and ana<strong>to</strong>my <strong>in</strong> three variants of primary<br />

progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 55, 335-346.<br />

[71] Rab<strong>in</strong>ovici GD, Furst AJ, O’Neil JP, Rac<strong>in</strong>e CA, Morm<strong>in</strong>o<br />

EC, Baker SL, Chetty S, Patel P, Pagliaro TA, Klunk WE,<br />

Mathis CA, Rosen HJ, Miller BL, Jagust WJ (2007) 11C-PIB<br />

PET imag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Alzheimer disease and fron<strong>to</strong>temporal lobar<br />

degeneration. Neurology 68, 1205-1212.<br />

[72] Kipps CM Hodges JR (2005) Cognitive assessment for cl<strong>in</strong>icians.<br />

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76(Suppl 1), i22-30.<br />

[73] Hodges JR (2007) Cognitive Assessment for Cl<strong>in</strong>icians, Oxford<br />

University <strong>Press</strong>, USA.<br />

[74] Hodges JR (2007) Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia Syndromes,<br />

Cambridge University <strong>Press</strong>, UK.<br />

[75] Gregory CA, Orrell M, Sahakian B, Hodges JR (1997) Can<br />

fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease be differ-

J.R. Burrell and J.R. Hodges / <strong>From</strong> <strong>FUS</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Fibs</strong>: What’s <strong>New</strong> <strong>in</strong> Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia? 359<br />

entiated us<strong>in</strong>g a brief battery of tests? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry<br />

12, 375-383.<br />

[76] Mathuranath PS, Nes<strong>to</strong>r PJ, Berrios GE, Rakowicz W,<br />

Hodges JR (2000) A brief cognitive test battery <strong>to</strong> differentiate<br />

Alzheimer’s disease and fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia. Neurology<br />

55, 1613-1620.<br />

[77] Mioshi E, Dawson K, Mitchell J, Arnold R, Hodges JR (2006)<br />

The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Exam<strong>in</strong>ation Revised (ACE-<br />

R): a brief cognitive test battery for dementia screen<strong>in</strong>g. Int<br />

J Geriatr Psychiatry 21, 1078-1085.<br />

[78] Frontier: Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia Research Group, http://<br />

www.ftdrg.org/, Accessed 10 March 2010.<br />

[79] Gregory CA, Serra-Mestres J, Hodges JR (1999) Early diagnosis<br />

of the frontal variant of fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia:<br />

how sensitive are standard neuroimag<strong>in</strong>g and neuropsychologic<br />

tests? Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 12,<br />

128-135.<br />

[80] Torralva T, Kipps CM, Hodges JR, Clark L, Bek<strong>in</strong>schte<strong>in</strong><br />

T, Roca M, Calcagno ML, Manes F (2007) The relationship<br />

between affective decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g and theory of m<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong> the<br />

frontal variant of fron<strong>to</strong>-temporal dementia. Neuropsychologia<br />

45, 342-349.<br />

[81] Torralva T, Roca M, Gleichgerrcht E, Bek<strong>in</strong>schte<strong>in</strong> T, Manes<br />

F (2009) A neuropsychological battery <strong>to</strong> detect specific executive<br />

and social cognitive impairments <strong>in</strong> early fron<strong>to</strong>temporal<br />

dementia. Bra<strong>in</strong> 132, 1299-1309.<br />

[82] Keane J, Calder AJ, Hodges JR, Young AW (2002) Face and<br />

emotion process<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> frontal variant fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia.<br />

Neuropsychologia 40, 655-665.<br />

[83] Rank<strong>in</strong> KP, Gorno-Temp<strong>in</strong>i ML, Allison SC, Stanley CM,<br />

Glenn S, We<strong>in</strong>er MW, Miller BL (2006) Structural ana<strong>to</strong>my<br />

of empathy <strong>in</strong> neurodegenerative disease. Bra<strong>in</strong> 129, 2945-<br />

2956.<br />

[84] Rank<strong>in</strong> KP, Salazar A, Gorno-Temp<strong>in</strong>i ML, Sollberger M,<br />

Wilson SM, Pavlic D, Stanley CM, Glenn S, We<strong>in</strong>er MW,<br />

Miller BL (2009) Detect<strong>in</strong>g sarcasm from paral<strong>in</strong>guistic<br />

cues: Ana<strong>to</strong>mic and cognitive correlates <strong>in</strong> neurodegenerative<br />

disease. NeuroImage 47, 2005-2015.<br />

[85] Gregory C, Lough S, S<strong>to</strong>ne V, Erz<strong>in</strong>clioglu S, Mart<strong>in</strong> L,<br />

Baron-Cohen S, Hodges JR (2002) Theory of m<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong><br />

patients with frontal variant fron<strong>to</strong>temporal dementia and<br />

Alzheimer’s disease: theoretical and practical implications.<br />

Bra<strong>in</strong> 125, 752-764.<br />

[86] Hodges JR, Mart<strong>in</strong>os M, Woollams AM, Patterson K, Adlam<br />

AR (2008) Repeat and Po<strong>in</strong>t: differentiat<strong>in</strong>g semantic<br />

dementia from progressive non-fluent aphasia. Cortex 44,<br />

1265-1270.<br />

[87] Diehl-Schmid J, Schulte-Overberg J, Hartmann J, Förstl H,<br />

Kurz A, Häussermann P (2007) Extrapyramidal signs, primitive<br />

reflexes and <strong>in</strong>cont<strong>in</strong>ence <strong>in</strong> fron<strong>to</strong>-temporal dementia.<br />

Eur J Neurol 14, 860-864.<br />

[88] Padovani A, Agosti C, Premi E, Bellelli G, Borroni B<br />

(2007) Extrapyramidal symp<strong>to</strong>ms <strong>in</strong> Fron<strong>to</strong>temporal Dementia:<br />

Prevalence and cl<strong>in</strong>ical correlations. Neurosci Lett 422,<br />

39-42.<br />

[89] Garbutt S, Matl<strong>in</strong> A, Hellmuth J, Schenk AK, Johnson JK,<br />