Cognition and behaviour in motor neurone disease - ResearchGate

Cognition and behaviour in motor neurone disease - ResearchGate

Cognition and behaviour in motor neurone disease - ResearchGate

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Cognition</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>behaviour</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong><br />

Patricia Lillo <strong>and</strong> John R. Hodges<br />

Neuroscience Research Australia, University of New<br />

South Wales, Sydney, New South of Wales, Australia<br />

Correspondence to Dr Patricia Lillo, Neuroscience<br />

Research Australia, Barker St, R<strong>and</strong>wick, NSW 2031,<br />

Australia<br />

Tel: +612 9399 1803; e-mail: p.lillo@neura.edu.au<br />

Current Op<strong>in</strong>ion <strong>in</strong> Neurology 2010, 23:638–642<br />

Introduction<br />

Motor <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong> (MND) has long been considered<br />

a pure <strong>motor</strong> system <strong>disease</strong>, but recent evidence has led<br />

to its reconceptualization as a multisystem <strong>disease</strong> [1].<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong>ically, up to 50% of patients with MND have cognitive<br />

impairment. Furthermore, 10–15% fulfil criteria<br />

for frontotemporal dementia (FTD) which we have<br />

designated MND-FTD [2]. A similar proportion of<br />

patients with FTD develop MND (FTD-MND) [3].<br />

Pathological f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs also support this overlap: MND<br />

patients <strong>and</strong> a subset of FTD cases have demonstrable<br />

TAR DNA b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong> 43 (TDP-43) <strong>in</strong>clusions [4].<br />

Here we review cognitive <strong>and</strong> <strong>behaviour</strong>al changes <strong>in</strong><br />

patients with MND <strong>in</strong> the context of recent pathological<br />

<strong>and</strong> genetic advances.<br />

Pathological overlap with frontotemporal<br />

dementia<br />

A major advance has been the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g that TDP-43 is the<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>cipal component <strong>in</strong> frontotemporal lobar degeneration<br />

Purpose of review<br />

Motor <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong> has traditionally been considered a pure <strong>motor</strong> syndrome which<br />

spares aspects of cognition <strong>and</strong> <strong>behaviour</strong>, although <strong>in</strong> recent years it has been<br />

suggested that up to 50% of patients with <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong> may develop frontal<br />

dysfunction which, <strong>in</strong> some cases, is severe enough to reach criteria for frontotemporal<br />

dementia. We review the cognitive <strong>and</strong> <strong>behaviour</strong>al changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong><br />

emphasiz<strong>in</strong>g the recent advances.<br />

Recent f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

A major advance <strong>in</strong> pathology has been the recent discovery of TDP-43 <strong>and</strong> FUS<br />

<strong>in</strong>clusions as the key components <strong>in</strong> cases of <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong>, frontotemporal<br />

dementia–<strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong> <strong>and</strong> some cases with pure frontotemporal dementia.<br />

In addition, mutations <strong>in</strong> TARDBP <strong>and</strong> FUS genes have been reported <strong>in</strong> recent years.<br />

Longitud<strong>in</strong>al studies showed that progression of cognitive impairment over the course<br />

of <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong> appears to be mild <strong>and</strong> occurs only <strong>in</strong> a proportion of <strong>motor</strong><br />

<strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong> patients. The presence of cognitive impairment seems to be related to<br />

a faster <strong>disease</strong> <strong>and</strong> a shorter survival.<br />

Summary<br />

Motor <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong> is a multi-system disorder which overlaps with frontotemporal<br />

dementia. Behavioural <strong>and</strong> cognitive changes appear to occur <strong>in</strong> a subset of patients<br />

with <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong>, but the cause of this variability rema<strong>in</strong>s unclear.<br />

Keywords<br />

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, <strong>behaviour</strong>al changes, cognitive impairment,<br />

frontotemporal dementia, <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong><br />

Curr Op<strong>in</strong> Neurol 23:638–642<br />

ß 2010 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s<br />

1350-7540<br />

with ubiquit<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>in</strong>clusions (FTLD-U), currently classified<br />

as FTLD-TDP. The condition is found <strong>in</strong> those<br />

patients who present with FTD but develop frank<br />

MND (FTD-MND), approximately a half of those with<br />

uncomplicated FTD <strong>and</strong> the majority of patients with<br />

both sporadic <strong>and</strong> familial MND. TDP-43 is a nuclear<br />

prote<strong>in</strong> of 43 kDa, which participates <strong>in</strong> various critical<br />

biological processes by b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g DNA <strong>and</strong> RNA. Normally,<br />

it is localized <strong>in</strong> nuclei of neurons <strong>and</strong> glial cells. Pathologically,<br />

normal nuclear TDP-43 sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is absent, <strong>and</strong><br />

cytoplasmic <strong>and</strong> nuclear TDP-43 <strong>in</strong>clusions are detectable<br />

[4]. Five patterns of TDP-43 aggregation are recognized.<br />

Pure MND, type 5, is characterized by cytoplasmic<br />

<strong>in</strong>clusions (ske<strong>in</strong>-like or dense granular), affect<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>cipally<br />

the <strong>motor</strong> cortex, the sp<strong>in</strong>al cord, basal ganglia <strong>and</strong><br />

thalamus. FTD-MND is usually associated with type 2,<br />

which is characterized by neuronal cytoplasmic <strong>in</strong>clusions<br />

<strong>in</strong> superficial <strong>and</strong> deep cortical layers <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

temporal <strong>and</strong> frontal cortices, dentate gyrus, amygdala<br />

<strong>and</strong> subcortical white matter [5 ]. As expected, the degree<br />

of neuronal loss is more <strong>in</strong> FTD-MND than <strong>in</strong> pure MND<br />

<strong>and</strong> affects primarily the anterior c<strong>in</strong>gulate gyrus, substantia<br />

nigra <strong>and</strong> amygdala [6,7].<br />

1350-7540 ß 2010 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s DOI:10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283400b41<br />

Copyright © Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

In addition, another prote<strong>in</strong> called FUS/TLS (fused <strong>in</strong><br />

sarcoma/translated <strong>in</strong>to liposarcoma), a 526-am<strong>in</strong>o-acid<br />

DNA/RNA b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong>, has been very recently<br />

identified <strong>in</strong> pathological cases of FTLD-U without<br />

TDP-43 <strong>in</strong>clusions [8]. The disorder is characterized<br />

by neuronal cytoplasmic <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tra-nuclear <strong>in</strong>clusions<br />

immunoreactive for FUS. This pattern has been also<br />

been found <strong>in</strong> cases with pure MND, MND-FTD <strong>and</strong><br />

cases of <strong>behaviour</strong>al variant FTD [9,10].<br />

Genetics<br />

There has been a recent explosion of knowledge <strong>in</strong> MND<br />

<strong>and</strong> FTD genetics, although the exact relationship<br />

between the identified genes <strong>and</strong> pathology rema<strong>in</strong>s<br />

unclear. A prom<strong>in</strong>ent family history is present <strong>in</strong> around<br />

5–10% of the patients with MND. It is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

note that the Cu–Zn superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1)<br />

mutation, which accounts for 15–20% of autosomal dom<strong>in</strong>ant<br />

familial cases, is characterized by lack of TDP-43<br />

<strong>and</strong> FUS <strong>in</strong>clusions <strong>and</strong> an apparent absence of cognitive<br />

<strong>in</strong>volvement [9,11 ,12].<br />

A second gene now l<strong>in</strong>ked to both familial <strong>and</strong> sporadic<br />

MND is the TAR DNA b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong> (TARDBP) gene<br />

on chromosome 1p36.22, designated ALS10. It is present<br />

<strong>in</strong> 1–3% of MND cases, <strong>and</strong> over 30 mutations have been<br />

identified with an autosomal dom<strong>in</strong>ant pattern of <strong>in</strong>heritance.<br />

Two cases present<strong>in</strong>g with FTD-MND have been<br />

reported; one with language deficits <strong>and</strong> the other with<br />

<strong>behaviour</strong>al impairment. Only one sporadic case with<br />

pure FTD with a TARDBP mutation has, so far, been<br />

reported [11 ,13].<br />

The third group, classified as ALS6, have mutations <strong>in</strong><br />

the fused sarcoma/translocation <strong>in</strong> liposarcoma gene<br />

(FUS/TLS), on chromosome 16q12. Dom<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>and</strong> recessive<br />

mutations have been identified <strong>in</strong> familial <strong>and</strong><br />

sporadic MND cases, <strong>and</strong> one case of sporadic FTD<br />

[11 ,12,14].<br />

Other mutations l<strong>in</strong>ked to MND cases with FTD are<br />

missense mutations <strong>in</strong> angiogen<strong>in</strong> (ANG) gene <strong>and</strong><br />

mutations <strong>in</strong> the p150 subunit of dynact<strong>in</strong> 1 (DCTN1)<br />

gene. In addition, two mutations reported <strong>in</strong> FTD<br />

cases, affect<strong>in</strong>g chromat<strong>in</strong>-modify<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong> 2B<br />

(CHMP2B) <strong>and</strong> progranul<strong>in</strong>e (PGRN) genes, although<br />

uncommon, have been found <strong>in</strong> cases with FTD <strong>and</strong><br />

MND [12].<br />

There are clearly more genes to be identified which are<br />

likely to be more common than some of the known<br />

mutations. A significant number of families <strong>in</strong> which<br />

some members have MND, FTD or both have been<br />

l<strong>in</strong>ked to chromosome 9, but the gene responsible<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>s elusive [15].<br />

<strong>Cognition</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>behaviour</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong> Lillo <strong>and</strong> Hodges 639<br />

Development of <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

patients with frontotemporal dementia<br />

Approximately, 15% of the patients with FTD develop<br />

frank MND <strong>in</strong> the course of the <strong>disease</strong> [3,16]. This<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>ical syndrome has a fairly consistent pattern <strong>in</strong> which<br />

rapidly evolv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>behaviour</strong>al <strong>and</strong> cognitive symptoms are<br />

followed after a period of 1–2 years later (sometimes up<br />

to 7 years) by bulbar <strong>and</strong> other signs of <strong>motor</strong> dysfunction<br />

[17,18 ]. The presentation may be with either <strong>behaviour</strong>al<br />

or language impairment, but usually both are<br />

present from the start.<br />

The <strong>behaviour</strong>al changes <strong>in</strong>clude poor <strong>in</strong>sight, lack of<br />

empathy, obsessions <strong>and</strong> tendency to eat sweet food <strong>and</strong><br />

hoard th<strong>in</strong>gs. Periods of apathy alternate with irritability<br />

<strong>and</strong> dis<strong>in</strong>hibition. The language impairment is characterized<br />

by a progressive nonfluent aphasia, lead<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

mutism [17]. A detailed case study of five patients with<br />

marked aphasia <strong>in</strong> association with MND documented a<br />

selective deficit <strong>in</strong> verb process<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g both production<br />

<strong>and</strong> comprehension. These patients were shown<br />

to have pathological <strong>in</strong>volvement of Broca’s area [19].<br />

Neuropsychological assessment often reveals prom<strong>in</strong>ent<br />

frontal/executive dysfunction. Although psychotic<br />

symptoms appear to be <strong>in</strong>frequent <strong>in</strong> FTD, remarkably,<br />

delusionshavebeenreported<strong>in</strong>upto50%ofpatients<br />

with the FTD-MND phenotype. Recent reports have<br />

focused attention on the presence of delusions <strong>in</strong> early<br />

stages of the <strong>disease</strong>, which have been described as<br />

persecutory type, phantom boarder syndrome, erotomania,<br />

bodily <strong>in</strong>vasion <strong>and</strong> delusional pregnancy [18 ,20 ].<br />

The course of the <strong>disease</strong>, with survival from diagnosis of<br />

2–3 years, is certa<strong>in</strong>ly shorter than <strong>in</strong> cases with pure<br />

FTD [18 ].<br />

Executive dysfunction<br />

The greatest body of literature on cognition <strong>in</strong> MND has<br />

related to executive function <strong>and</strong> by implication to prefrontal<br />

lobe abilities [2,21–24] (Table 1). Although estimates<br />

of the prevalence of such deficits range from 10 to<br />

70%, <strong>in</strong> the largest study to date subtle cognitive impairment<br />

was found <strong>in</strong> 50% of 279 patients with sporadic<br />

MND [2].<br />

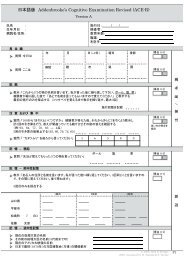

Table 1 Summary of cognitive <strong>and</strong> <strong>behaviour</strong>al changes <strong>in</strong><br />

patients with <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong><br />

Deficits caused by cognitive impairment Behavioural changes<br />

Attention Apathy<br />

Verbal fluency Irritability<br />

Work<strong>in</strong>g memory Lack of empathy<br />

Plann<strong>in</strong>g/organiz<strong>in</strong>g Dis<strong>in</strong>hibition<br />

Mental shift<strong>in</strong>g Compulsions<br />

Stereotyped <strong>behaviour</strong>s<br />

Data from [21–27,28 ].<br />

Copyright © Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

640 Degenerative <strong>and</strong> cognitive <strong>disease</strong>s<br />

The most prom<strong>in</strong>ent deficit reported has been reduction<br />

<strong>in</strong> verbal fluency, which is evident <strong>in</strong> the letter fluency<br />

test [24,25]. This impairment has been associated with<br />

dysfunction of anterior c<strong>in</strong>gulate gyrus <strong>and</strong> middle <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>ferior frontal gyri as demonstrated by functional MRI<br />

[25]. Written rather verbal fluency has been exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong><br />

patients with significant dysarthria [24]. Attention (verbal<br />

series attention test <strong>and</strong> paced auditory serial addition<br />

test), work<strong>in</strong>g memory (reverse digit span test), plann<strong>in</strong>g<br />

(Tower of Hanoi) <strong>and</strong> cognitive flexibility (Wiscons<strong>in</strong><br />

card sort<strong>in</strong>g test) may also be impaired [21–24]. As<br />

impaired performance on neuropsychological assessment<br />

can be confounded by <strong>motor</strong> dysfunction, a recent study<br />

assessed executive function with a <strong>motor</strong>-free test. In this<br />

study, the performance of MND patients <strong>and</strong> controls<br />

was compared us<strong>in</strong>g the Medication Schedul<strong>in</strong>g Task,<br />

which <strong>in</strong>cludes plann<strong>in</strong>g, multitask<strong>in</strong>g, mental set shift<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>and</strong> delay<strong>in</strong>g response components. The participants<br />

were asked to assemble a daily safe scheme for the<br />

adm<strong>in</strong>istration of the medication. Despite correction<br />

for <strong>motor</strong> disability, MND patients performed worse than<br />

the control group [26].<br />

Behavioural symptoms<br />

A range of <strong>behaviour</strong>al symptoms that parallel those<br />

found <strong>in</strong> FTD have been reported although, as with<br />

cognitive dysfunction, estimates of prevalence vary considerably.<br />

Apathy has been consistently found to be the<br />

most common feature. For <strong>in</strong>stance, one study reported<br />

apathy <strong>in</strong> 55% of MND patients, which correlated with<br />

deficits <strong>in</strong> verbal fluency but not with physical disability,<br />

mood disturbances or respiratory function [27]. A study<br />

on 225 MND patients, which used the Frontal Systems<br />

Behaviour Scale (FrSBe) designed to evaluate apathy,<br />

executive dysfunction <strong>and</strong> dis<strong>in</strong>hibition, showed an<br />

elevation <strong>in</strong> the total FrSBe score <strong>in</strong> a quarter of cases<br />

<strong>and</strong> over a third of cases had impairment <strong>in</strong> at least one<br />

<strong>behaviour</strong>al doma<strong>in</strong>. Patients with cognitive impairment<br />

had greater <strong>behaviour</strong>al changes, although the two<br />

doma<strong>in</strong>s were partially <strong>in</strong>dependent [28 ]. F<strong>in</strong>ally, two<br />

<strong>in</strong>formant-based <strong>behaviour</strong>al <strong>in</strong>terview surveys showed<br />

that patients with MND may also present <strong>in</strong>discrim<strong>in</strong>ate<br />

eat<strong>in</strong>g, gluttony, compulsions <strong>and</strong> <strong>behaviour</strong>al stereotypes<br />

[29,30] (see Table 1).<br />

Memory<br />

A majority of the studies assess<strong>in</strong>g memory have shown<br />

greater impairment of immediate recall than with recognition<br />

tasks, suggest<strong>in</strong>g a retrieval disturbance secondary<br />

to prefrontal dysfunction [21,31]. A recent meta-analysis<br />

of studies to date concluded that some aspects of memory<br />

are consistently impaired, notably immediate <strong>and</strong><br />

delayed visual memory <strong>and</strong> immediate verbal memory.<br />

The pattern is <strong>in</strong> keep<strong>in</strong>g with frontal lobe dysfunction,<br />

but <strong>in</strong>volvement of temporal lobe structures could not be<br />

discounted because of the effect size [32 ].<br />

Language<br />

Language assessment presents particular problems <strong>in</strong><br />

patients with dysarthria, but even allow<strong>in</strong>g for this it<br />

seems that significant aphasia occurs <strong>in</strong> a proportion of<br />

patients with MND <strong>and</strong> may be more common <strong>in</strong><br />

patients with bulbar onset <strong>disease</strong> [33]. The most commonly<br />

identified deficits have been reduced speech<br />

output <strong>and</strong> anomia [17,34]. Some patients develop significant<br />

aphasia designated progressive nonfluent aphasia<br />

with agrammatism <strong>in</strong> production <strong>and</strong> impaired syntactic<br />

comprehension. Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, a higher order disturbance<br />

of <strong>motor</strong> speech, apraxia of speech, has been reported <strong>in</strong><br />

patients with bulbar onset <strong>disease</strong>, frequently associated<br />

with spastic or mixed spastic–flaccid dysarthria [35].<br />

Emotional process<strong>in</strong>g<br />

The fact that emotion process<strong>in</strong>g is severely <strong>and</strong> consistently<br />

compromised <strong>in</strong> patients with FTD [36] has underst<strong>and</strong>ably<br />

led a number of <strong>in</strong>vestigators to study this<br />

aspect of social cognition <strong>in</strong> MND. Impaired recognition<br />

of emotional faces was found <strong>in</strong> a group of bulbar MND<br />

patients [37]. A selective deficit <strong>in</strong> the recognition of<br />

threat stimuli through faces has also been reported, which<br />

parallels that seen <strong>in</strong> patients with amygdala damage [38].<br />

Longitud<strong>in</strong>al studies<br />

A key question unanswered from cross-sectional studies<br />

is whether cognitive dysfunction rema<strong>in</strong>s conf<strong>in</strong>ed to a<br />

subset of patients with MND whose condition worsens<br />

over time or alternatively whether all patients with MND<br />

eventually develop cognitive or <strong>behaviour</strong>al changes.<br />

Longitud<strong>in</strong>al studies have found cognitive dysfunction<br />

early <strong>in</strong> the course of the <strong>disease</strong>, on the basis of verbal<br />

fluency deficits [39] particularly <strong>in</strong> those with bulbar<br />

onset <strong>disease</strong> [40], although this has not been a universal<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g [41,42 ].<br />

Progression of cognitive impairment over the course of<br />

MND appears to be mild. Older patients, <strong>and</strong> those with<br />

more rapidly progress<strong>in</strong>g <strong>disease</strong>, may be more predisposed<br />

to cognitive impairment, which, <strong>in</strong> turn, contributes<br />

to a shorter survival [42 ].<br />

Neuroimag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

The pr<strong>in</strong>cipal role of neuroimag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> MND has been to<br />

exclude alternative diagnoses, although <strong>in</strong> more recent<br />

years new techniques have been used to assess the<br />

<strong>in</strong>tegrity of both the <strong>motor</strong> system <strong>and</strong> the extra <strong>motor</strong><br />

regions.<br />

Copyright © Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Structural MRI has established that those with subtle<br />

cognitive or <strong>behaviour</strong>al impairment showed grey matter<br />

loss <strong>in</strong> frontal, parietal <strong>and</strong> limbic regions [43 ]. As<br />

expected, patients with MND-FTD have atrophy of<br />

frontotemporal lobes <strong>and</strong> hyper<strong>in</strong>tensity of subcortical<br />

white matter <strong>in</strong> medial anterior temporal lobe, similar to<br />

that seen <strong>in</strong> patients with pure FTD [44,45].<br />

A comparison of MND <strong>and</strong> MND-FTD patient groups<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g voxel-based morphometry showed a similar pattern<br />

of grey matter atrophy <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g bilateral <strong>motor</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

pre<strong>motor</strong> cortices, superior, middle <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ferior frontal<br />

gyri, superior temporal gyri, temporal poles <strong>and</strong> left<br />

posterior thalamus that was, as predicted, greater <strong>in</strong><br />

the MND-FTD group [46].<br />

Functional MRI (fMRI) studies have shown reduced<br />

activation of the middle <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ferior frontal gyri <strong>and</strong><br />

anterior c<strong>in</strong>gulate gyrus <strong>in</strong> MND patients dur<strong>in</strong>g letter<br />

fluency tasks [29]. Deficits on word fluency <strong>and</strong> confrontation<br />

nam<strong>in</strong>g have been shown to correlate with<br />

impaired activation of the prefrontal region (Broca area),<br />

temporal, parietal <strong>and</strong> occipital lobes [29,43 ].<br />

A few recent studies have exam<strong>in</strong>ed the relationship<br />

between social process<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> regions of bra<strong>in</strong> activation<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g fMRI. One study demonstrated that patients with<br />

MND present<strong>in</strong>g altered sensitivity to social–emotional<br />

clues had an <strong>in</strong>creased response <strong>in</strong> the right supramarg<strong>in</strong>al<br />

area [47]. Another showed that impaired emotional<br />

process <strong>in</strong> ALS patients was related to right hemisphere<br />

dysfunction [48].<br />

Conclusion<br />

Recent advances <strong>in</strong> genetics <strong>and</strong> pathology have led to<br />

the concept of MND as a multisystem disorder which<br />

overlaps with frontotemporal dementia. The assessment<br />

of patients with MND is challeng<strong>in</strong>g, due to the <strong>motor</strong><br />

disability <strong>and</strong> the variability of the cl<strong>in</strong>ical phenotype. It<br />

appears that changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>behaviour</strong> <strong>and</strong> cognition, notably<br />

executive function, language <strong>and</strong> emotional process<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

occurs only <strong>in</strong> a subset of patients, but the cause of this<br />

variability <strong>in</strong> the cl<strong>in</strong>ical phenotype rema<strong>in</strong>s unclear.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The study was supported by the Australian Research Council<br />

Federation Fellowship, FF0776229 (Prof. Hodges) <strong>and</strong> CONICYT<br />

scholarship (Government of Chile) (Dr Lillo).<br />

J.R.H. serves on editorial boards of Aphasiology, Cognitive Neuropsychiatry,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Cognitive Neuropsychology; receives royalties from<br />

publication of Cognitive Assessment for Cl<strong>in</strong>icians (Oxford University<br />

Press, 2007) <strong>and</strong> Frontotemporal Dementia Syndromes (Cambridge<br />

University Press, 2007) <strong>and</strong> receives fellowship support from the<br />

Australian Research Council Federation.<br />

Thanks to Dr James Burrell, MBBS (Hons), for his assistance with<br />

proofread<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

<strong>Cognition</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>behaviour</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong> Lillo <strong>and</strong> Hodges 641<br />

References <strong>and</strong> recommended read<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Papers of particular <strong>in</strong>terest, published with<strong>in</strong> the annual period of review, have<br />

been highlighted as<br />

of special <strong>in</strong>terest<br />

of outst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terest<br />

Additional references related to this topic can also be found <strong>in</strong> the Current<br />

World Literature section <strong>in</strong> this issue (p. 708).<br />

1 Geser F, Br<strong>and</strong>meir NJ, Kwong LK, et al. Evidence of multisystem disorder <strong>in</strong><br />

whole-bra<strong>in</strong> map of pathological TDP-43 <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch<br />

Neurol 2008; 65:636–641.<br />

2 R<strong>in</strong>gholz GM, Appel SH, Bradshaw M, et al. Prevalence <strong>and</strong> patterns of<br />

cognitive impairment <strong>in</strong> sporadic ALS. Neurology 2005; 65:586–590.<br />

3 Lomen-Hoerth C, Anderson T, Miller B. The overlap of amyotrophic lateral<br />

sclerosis <strong>and</strong> frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2002; 59:1077–1079.<br />

4 Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, et al. Ubiquit<strong>in</strong>ated TDP-43 <strong>in</strong><br />

frontotemporal lobar degeneration <strong>and</strong> amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science<br />

2006; 314:130–133.<br />

5 Geser F, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis <strong>and</strong><br />

frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a spectrum of TDP-43 prote<strong>in</strong>opathies.<br />

Neuropathology 2010; 30:103–112.<br />

A complete description of the pathology <strong>in</strong> MND with specific emphasis on the<br />

distribution of TDP-43 <strong>in</strong>clusions.<br />

6 Kersaitis C, Halliday GM, Xuereb JH, et al. Ubiquit<strong>in</strong>-positive <strong>in</strong>clusions <strong>and</strong><br />

progression of pathology <strong>in</strong> frontotemporal dementia <strong>and</strong> <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong><br />

<strong>disease</strong> identifies a group with ma<strong>in</strong>ly early pathology. Neuropathol Appl<br />

Neurobiol 2006; 32:83–91.<br />

7 Geser F, Mart<strong>in</strong>ez-Lage M, Rob<strong>in</strong>son J, et al. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical <strong>and</strong> pathological<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>uum of multisystem TDP-43 prote<strong>in</strong>opathies. Arch Neurol 2009;<br />

66:180–189.<br />

8 Neumann M, Rademakers R, Roeber S, et al. A new subtype of frontotemporal<br />

lobar degeneration with FUS pathology. Bra<strong>in</strong> 2009; 132:2922–2931.<br />

9 Deng HX, Zhai H, Bigio EH, et al. FUS-immunoreactive <strong>in</strong>clusions are a<br />

common feature <strong>in</strong> sporadic <strong>and</strong> non-SOD1 familial amyotrophic lateral<br />

sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2010; 67:739–748.<br />

10 Urw<strong>in</strong> H, Josephs KA, Rohrer JD, et al. FUS pathology def<strong>in</strong>es the majority of<br />

tau- <strong>and</strong> TDP-43-negative frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol<br />

2010; 120:33–41.<br />

11 Dion PA, Daoud H, Rouleau GA. Genetics of <strong>motor</strong> neuron disorders: new<br />

<strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong>to pathogenic mechanisms. Nat Rev Genet 2009; 10:769–782.<br />

An excellent update on the genetic f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs across <strong>motor</strong> neuron <strong>disease</strong> with a<br />

brief <strong>and</strong> clear explanation of the pathogenic mechanism <strong>and</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical presentation.<br />

12 Millecamps S, Salachas F, Cazeneuve C, et al. SOD1, ANG, VAPB, TARDBP,<br />

<strong>and</strong> FUS mutations <strong>in</strong> familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: genotype–<br />

phenotype correlations. J Med Genet 2010; 47:554–560.<br />

13 Benajiba L, Le Ber I, Camuzat A, et al. TARDBP mutations <strong>in</strong> motoneuron<br />

<strong>disease</strong> with frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Ann Neurol 2009; 65:470–<br />

473.<br />

14 Van Langenhove T, van der Zee J, Sleegers K, et al. Genetic contribution of<br />

FUS to frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 2010; 74:366–371.<br />

15 Boxer AL, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, et al. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical, neuroimag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> neuropathological<br />

features of a new chromosome 9p-l<strong>in</strong>ked FTD-ALS family.<br />

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010; Jun 10 [Epub ahead of pr<strong>in</strong>t].<br />

16 Lomen-Hoerth C. Characterization of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis <strong>and</strong> frontotemporal<br />

dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2004; 17:337–341.<br />

17 Bak TH, Hodges JR. Motor <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong>, dementia <strong>and</strong> aphasia: co<strong>in</strong>cidence,<br />

co-occurrence or cont<strong>in</strong>uum? J Neurol 2001; 248:260–270.<br />

18 Lillo P, Garc<strong>in</strong> B, Hornberger M, et al. Neurobehavioral features <strong>in</strong> frontotemporal<br />

dementia with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2010;<br />

67:826–830.<br />

Provides <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g data compar<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>behaviour</strong>al symptoms of patients with<br />

FTD-MND vs. bvFTD <strong>and</strong> survival.<br />

19 Bak TH, O’Donovan DG, Xuereb JH, et al. Selective impairment of verb<br />

process<strong>in</strong>g associated with pathological changes <strong>in</strong> Brodmann areas 44 <strong>and</strong><br />

45 <strong>in</strong> the <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong>-dementia-aphasia syndrome. Bra<strong>in</strong> 2001;<br />

124:103–120.<br />

20 Loy CT, Kril JJ, Trollor JN, et al. The case of a 48 year-old woman with bizarre<br />

<strong>and</strong> complex delusions. Nat Rev Neurol 2010; 6:175–179.<br />

An unusual case with an excellent cl<strong>in</strong>ico-pathological correlation.<br />

21 Phukan J, Pender NP, Hardiman O. Cognitive impairment <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic<br />

lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2007; 6:994–1003.<br />

22 Woolley SC, Katz JS. Cognitive <strong>and</strong> behavioral impairment <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic<br />

lateral sclerosis. Phys Med Rehabil Cl<strong>in</strong> N Am 2008; 19:607–617.<br />

Copyright © Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

642 Degenerative <strong>and</strong> cognitive <strong>disease</strong>s<br />

23 Murphy JM, Henry RG, Langmore S, et al. Cont<strong>in</strong>uum of frontal lobe<br />

impairment <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2007; 64:530–<br />

534.<br />

24 Abrahams S, Leigh PN, Harvey A, et al. Verbal fluency <strong>and</strong> executive<br />

dysfunction <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Neuropsychologia<br />

25<br />

2000; 38:734–747.<br />

Abrahams S, Goldste<strong>in</strong> LH, Simmons A, et al. Word retrieval <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic<br />

lateral sclerosis: a functional magnetic resonance imag<strong>in</strong>g study. Bra<strong>in</strong> 2004;<br />

127:1507–1517.<br />

26 Stukovnik V, Zidar J, Podnar S, Repovs G. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis<br />

patients show executive impairments on st<strong>and</strong>ard neuropsychological measures<br />

<strong>and</strong> an ecologically valid <strong>motor</strong>-free test of executive functions. J Cl<strong>in</strong><br />

Exp Neuropsychol 2010; 24:1–15.<br />

27 Grossman AB, Woolley-Lev<strong>in</strong>e S, Bradley WG, Miller RG. Detect<strong>in</strong>g neurobehavioral<br />

changes <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler<br />

2007; 8:56–61.<br />

28 Witgert M, Salamone AR, Strutt AM, et al. Frontal-lobe mediated behavioral<br />

dysfunction <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2010; 17:103–<br />

110.<br />

The largest study of <strong>behaviour</strong>al changes <strong>in</strong> MND patients with neuropsychological<br />

correlation.<br />

29 Gibbons ZC, Richardson A, Neary D, Snowden JS. Behaviour <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic<br />

lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2008; 9:67–74.<br />

30 Lillo P, Mioshi E, Zo<strong>in</strong>g MC, et al. How common are <strong>behaviour</strong>al changes <strong>in</strong><br />

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2010; Sep 19 [Epub<br />

ahead of pr<strong>in</strong>t].<br />

31 Mantovan MC, Baggio L, Dalla Barba G, et al. Memory deficits <strong>and</strong> retrieval<br />

processes <strong>in</strong> ALS. Eur J Neurol 2003; 10:221–227.<br />

32 Raaphorst J, de Visser M, L<strong>in</strong>ssen WH, et al. The cognitive profile of<br />

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler<br />

2010; 11:27–37.<br />

First meta-analysis <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a review of neuropsychological assessments.<br />

33 Abrahams S, Goldste<strong>in</strong> LH, AlChalabi A, et al. Relation between cognitive<br />

dysfunction <strong>and</strong> pseudobulbar palsy <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol<br />

Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997; 62:464–472.<br />

34 Bak TH, Hodges JR. The effects of <strong>motor</strong> <strong>neurone</strong> <strong>disease</strong> on language:<br />

further evidence. Bra<strong>in</strong> Lang 2004; 89:354–361.<br />

35 Duffy JR, Peach RK, Str<strong>and</strong> EA. Progressive apraxia of speech as a sign of<br />

<strong>motor</strong> neuron <strong>disease</strong>. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2007; 16:198–208.<br />

36 Lough S, Kipps CM, Treise C, et al. Social reason<strong>in</strong>g, emotion <strong>and</strong> empathy <strong>in</strong><br />

frontotemporal dementia. Neuropsychologia 2006; 44:950–958.<br />

37 Zimmerman EK, Esl<strong>in</strong>ger PJ, Simmons Z, Barrett AM. Emotional perception<br />

deficits <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cogn Behav Neurol 2007; 20:79–<br />

82.<br />

38 Schmolck H, Mosnik D, Schulz P. Rat<strong>in</strong>g the approachability of faces <strong>in</strong> ALS.<br />

Neurology 2007; 69:2232–2235.<br />

39 Abrahams S, Leigh PN, Goldste<strong>in</strong> LH. Cognitive change <strong>in</strong> ALS: a prospective<br />

study. Neurology 2005; 64:1222–1226.<br />

40 Schreiber H, Gaigalat T, Wiedemuth-Catr<strong>in</strong>escu U, et al. Cognitive function <strong>in</strong><br />

bulbar- <strong>and</strong> sp<strong>in</strong>al-onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a longitud<strong>in</strong>al study <strong>in</strong><br />

52 patients. J Neurol 2005; 252:772–781.<br />

41 Rob<strong>in</strong>son KM, Lacey SC, Grugan P, et al. Cognitive function<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> sporadic<br />

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a six month longitud<strong>in</strong>al study. J Neurol Neurosurg<br />

Psychiatry 2006; 77:668–670.<br />

42 Gordon PH, Goetz RR, Rabk<strong>in</strong> JG, et al. A prospective cohort study of<br />

neuropsychological test performance <strong>in</strong> ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2010;<br />

11:312–320.<br />

Analyses the previous longitud<strong>in</strong>al studies <strong>and</strong> br<strong>in</strong>gs analysis on groups of risk for<br />

cognitive impairment <strong>and</strong> shorter survival.<br />

43 Agosta F, Chio A, Cosott<strong>in</strong>i M, et al. The present <strong>and</strong> the future of neuroimag<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010; Apr 1<br />

[Epub ahead of pr<strong>in</strong>t].<br />

A complete review of the neuroimag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>motor</strong> <strong>and</strong> extra<strong>motor</strong> bra<strong>in</strong> areas.<br />

44 Mori H, Yagishita A, Takeda T, Mizutani T. Symmetric temporal abnormalities<br />

on MR imag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with dementia. AJNR Am J<br />

Neuroradiol 2007; 28:1511–1516.<br />

45 Mezzapesa DM, Ceccarelli A, Dicuonzo F, et al. Whole-bra<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> regional<br />

bra<strong>in</strong> atrophy <strong>in</strong> amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007;<br />

28:255–259.<br />

46 Chang JL, Lomen-Hoerth C, Murphy J, et al. A voxel-based morphometry study<br />

of patterns of bra<strong>in</strong> atrophy <strong>in</strong> ALS <strong>and</strong> ALS/FTLD. Neurology 2005; 65:75–<br />

80.<br />

47 Lule D, Diekmann V, Anders S, et al. Bra<strong>in</strong> responses to emotional stimuli <strong>in</strong><br />

patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). J Neurol 2007; 254:519–<br />

527.<br />

48 Palmieri A, Naccarato M, Abrahams S, et al. Right hemisphere dysfunction<br />

<strong>and</strong> emotional process<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> ALS: an fMRI study. J Neurol 2010; Jul 1 [Epub<br />

ahead of pr<strong>in</strong>t].<br />

Copyright © Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.