View - ResearchGate

View - ResearchGate

View - ResearchGate

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

EDITORIALS<br />

Towards evidence-based dementia screening in Australia<br />

Zoe Terpening, John R Hodges and Nicholas J Cordato<br />

Effective dementia care depends on early and accurate diagnosis<br />

t is predicted that over the next 40 years there will be a<br />

fourfold increase in the prevalence of dementia in Australia, as<br />

well as considerably more people with milder forms of cognitive<br />

impairment. 1 To date, despite extensive research, no effective<br />

treatment for established dementia is available. As a result,<br />

taskforce policymakers conclude that there is insufficient evidence<br />

at present to warrant routine screening for dementia syndromes. 2,3<br />

However, emerging evidence shows that early non-pharmacological<br />

intervention can improve cognitive outcomes for patients with<br />

milder forms of cognitive impairment and those at risk of<br />

cognitive decline. 4 Early diagnosis also enables patients to plan,<br />

with their caregivers, for the future, and deal with matters such as<br />

enduring power of attorney authorisation, before they lose the<br />

capacity to do so. Over two-thirds of people who notice symptoms<br />

of cognitive decline consult a physician for evaluation. 5 However,<br />

up to 90% of mild cases are missed at the initial primary care<br />

assessment. 6,7 I<br />

So how can we improve early detection of cognitive<br />

impairment, and what evidence base do we have for dementia<br />

screening in Australia?<br />

A diagnosis of dementia relies on a full mental status assessment,<br />

with comprehensive history taking and physical examination. Presently,<br />

detailed neuropsychological testing is the gold-standard tool<br />

for objectively evaluating the magnitude and pattern of cognitive<br />

decline. However, neuropsychological evaluation is costly, timeconsuming<br />

and not generally available as only specialist psychologists<br />

can do it. Consequently, general practitioners and specialist<br />

60 MJA • Volume 194 Number 2 • 17 January 2011<br />

physicians, who evaluate most patients presenting with cognitive<br />

complaints, administer brief screening instruments such as the minimental<br />

state examination (MMSE) to assess cognition. In Australia,<br />

the use of such instruments has been propagated by guidelines for<br />

prescribing acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. The MMSE has many<br />

documented and widely appreciated shortcomings. It lacks diagnostic<br />

specificity and is insensitive to patient variables such as extreme<br />

levels of education, premorbid ability and poor command of<br />

English. 8 It has also been criticised for its unsystematic and atheoretical<br />

construction, and its poor ability to detect milder forms of<br />

cognitive impairment. 8,9<br />

The idea that any brief screening tool would have sufficient<br />

sensitivity and specificity to diagnose dementia is unrealistic. However,<br />

when used as an adjunct to a good clinical history, a more<br />

accurate instrument, particularly one that can be serially administered,<br />

would potentially increase the reliability of diagnosis. A recent<br />

review of screening instruments available for mild cognitive impairment<br />

concluded that there are more useful screening tools than the<br />

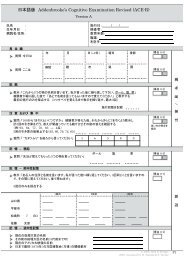

MMSE. 10 Some are in use in Australia, including the Addenbrooke’s<br />

Cognitive Examination – Revised (ACE-R); the Alzheimer’s Disease<br />

Assessment Scale — cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog); and the Montreal<br />

Cognitive Assessment battery. In addition, there are other<br />

screening instruments specifically validated for use in Australia,<br />

such as the General Practitioner assessment of Cognition (GPCog)<br />

and Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS).

EDITORIALS<br />

Recently, the ACE-R was validated for use in an Australian<br />

population. 11 The ACE-R, which incorporates the MMSE, has been<br />

shown to have more diagnostic sophistication, with improved<br />

sensitivity and specificity values, than the MMSE alone. This is not<br />

to say that the ACE-R is without limitations. For instance, it cannot<br />

fully assess some aspects of cognitive function (eg, non-verbal<br />

skills). Furthermore, the ACE-R takes on average 16 minutes to<br />

administer and is therefore unlikely to see much uptake by busy<br />

GPs; however, it could be used by nurses working in general<br />

practices. As with all screening tools, clinicians using the ACE-R in<br />

the primary care setting need to be trained to correctly score and<br />

interpret patients’ ACE-R performances.<br />

Development of effective dementia treatments depends on earlier<br />

and more accurate identification of disease. Cognitive screening tests<br />

will continue to evolve, and may in time be replaced with screening<br />

for disease-related biomarkers. However, such diagnostic biomarkers<br />

have yet to be discovered. With the number of people with<br />

dementia growing each year, the lack of adequately validated<br />

diagnostic tools is a serious concern. Empirical investigations to<br />

further evaluate and validate screening instruments for cognitive<br />

impairment are necessary as we strive to develop effective treatments<br />

for all forms of this debilitating disorder.<br />

Competing interests<br />

Nicholas Cordato has received a grant from the Medical Foundation,<br />

University of Sydney, to research Alzheimer’s disease.<br />

Author details<br />

Zoe Terpening, BPsych(Hons), MSc, DClinNeuropsych, Clinical<br />

Neuropsychologist1 John R Hodges, MD, FRCP, FMedSci, Federation Fellow and Professor<br />

of Cognitive Neurology2 Nicholas J Cordato, MB BS, PhD, FRACP, Senior Staff Specialist in<br />

Aged Care 3<br />

1 Ageing Brain Centre, Brain and Mind Research Institute, University of<br />

Sydney, Sydney, NSW.<br />

2 Prince of Wales Medical Research Institute, Sydney, NSW.<br />

3 Department of Aged Care, St George Hospital and Calvary<br />

Rehabilitation and Geriatric Service, Calvary Health Care, Sydney,<br />

NSW.<br />

Correspondence: zoe.terpening@sydney.edu.au<br />

References<br />

1 Access Economics. Keeping dementia front of mind: incidence and<br />

prevalence 2009–2050. 2009. http://www.accesseconomics.com.au/publicationsreports/getreport.php?report=214&id=272<br />

(accessed Nov<br />

2010).<br />

2 United Kingdom National Screening Committee. Policy database.<br />

Alzheimer’s disease. http://www.screening.nhs.uk/alzheimers (accessed<br />

Dec 2010).<br />

3 Boustani M, Peterson B, Harris R, et al. Screening for dementia. June<br />

2003. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of<br />

Health and Human Services. (AHRQ contract no. 290-97-0011.) http://<br />

www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/prevent/pdfser/dementser.pdf (accessed<br />

Dec 2010).<br />

4 Naismith S, Glozier N, Burke D, et al. Early intervention in cognitive<br />

decline: is there a role for multiple medical or behavioural interventions?<br />

Early Intervent Psychiatry 2009; 3: 19-27.<br />

5 Wilkinson D, Stave C, Keohane D, Vincenzino O. The role of general<br />

practitioners in the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a<br />

multinational survey. J Int Med Res 2004; 32: 149-159.<br />

6 Boustani M, Peterson B, Hanson L, et al. Screening for dementia in<br />

primary care: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services<br />

Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138: 927-937.<br />

7 Valcour VG, Masaki KH, Curb JD, Blanchette PL. The detection of<br />

dementia in the primary care setting. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 2964-<br />

2968.<br />

8 Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The mini-mental state examination: a<br />

comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40: 922-935.<br />

9 Zarit SH, Blazer D, Orrell M, Woods B. Throwing down the gauntlet: can<br />

we do better than the MMSE? Aging Ment Health 2008; 12: 411-412.<br />

10 Lonie JA, Tierney KM, Ebmeier KP. Screening for mild cognitive impairment:<br />

a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009; 24: 902-915.<br />

11 Terpening Z, Cordato N, Hepner I, et al. Utility of the Addenbrooke’s<br />

Cognitive Examination — Revised for the diagnosis of dementia syndromes.<br />

Australasian J Ageing 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-<br />

6612.2010.00446.x [17/08/10] ❏<br />

MJA • Volume 194 Number 2 • 17 January 2011 61