Contents - MUP-Extras

Contents - MUP-Extras Contents - MUP-Extras

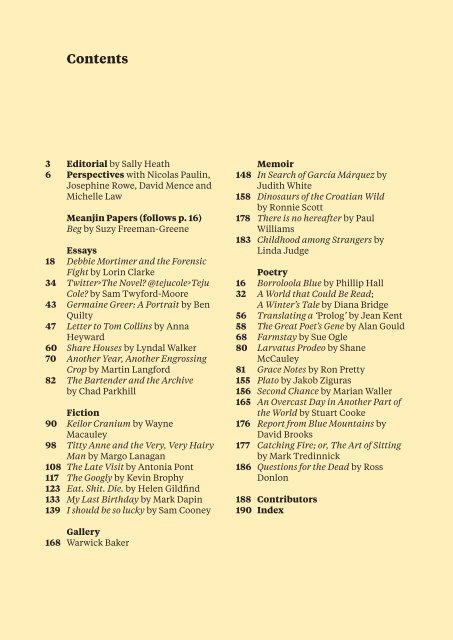

Contents 3 Editorial by Sally Heath 6 Perspectives with Nicolas Paulin, Josephine Rowe, David Mence and Michelle Law Meanjin Papers (follows p. 16) Beg by Suzy Freeman-Greene Essays 18 Debbie Mortimer and the Forensic Fight by Lorin Clarke 34 Twitter>The Novel? @tejucole>Teju Cole? by Sam Twyford-Moore 43 Germaine Greer: A Portrait by Ben Quilty 47 Letter to Tom Collins by Anna Heyward 60 Share Houses by Lyndal Walker 70 Another Year, Another Engrossing Crop by Martin Langford 82 The Bartender and the Archive by Chad Parkhill Fiction 90 Keilor Cranium by Wayne Macauley 98 Titty Anne and the Very, Very Hairy Man by Margo Lanagan 108 The Late Visit by Antonia Pont 117 The Googly by Kevin Brophy 123 Eat. Shit. Die. by Helen Gildfind 133 My Last Birthday by Mark Dapin 139 I should be so lucky by Sam Cooney Gallery 168 Warwick Baker Memoir 148 In Search of García Márquez by Judith White 158 Dinosaurs of the Croatian Wild by Ronnie Scott 178 There is no hereafter by Paul Williams 183 Childhood among Strangers by Linda Judge Poetry 16 Borroloola Blue by Phillip Hall 32 A World that Could Be Read; A Winter’s Tale by Diana Bridge 56 Translating a ‘Prolog’ by Jean Kent 58 The Great Poet’s Gene by Alan Gould 68 Farmstay by Sue Ogle 80 Larvatus Prodeo by Shane McCauley 81 Grace Notes by Ron Pretty 155 Plato by Jakob Ziguras 156 Second Chance by Marian Waller 165 An Overcast Day in Another Part of the World by Stuart Cooke 176 Report from Blue Mountains by David Brooks 177 Catching Fire; or, The Art of Sitting by Mark Tredinnick 186 Questions for the Dead by Ross Donlon 188 Contributors 190 Index Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 1 6/11/12 9:20 AM

- Page 2 and 3: Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 2 6/11/12 9

- Page 4 and 5: Meanjin Editor Sally Heath heath@un

- Page 6 and 7: Perspectives Game over for Space Ju

- Page 8 and 9: Perspectives Astrophysics (RSAA) at

- Page 10 and 11: Perspectives researched and transla

- Page 12 and 13: Perspectives fabrications and consp

- Page 14 and 15: Perspectives ‘How about both?’

- Page 16 and 17: Borroloola Blue Phillip Hall All ar

- Page 18 and 19: Debbie Mortimer and the Forensic Fi

- Page 20 and 21: Debbie Mortimer and the Forensic Fi

- Page 22 and 23: Debbie Mortimer and the Forensic Fi

- Page 24 and 25: Debbie Mortimer and the Forensic Fi

- Page 26 and 27: Debbie Mortimer and the Forensic Fi

- Page 28 and 29: Debbie Mortimer and the Forensic Fi

- Page 30 and 31: Debbie Mortimer and the Forensic Fi

- Page 32 and 33: A World that Could Be Read Diana Br

- Page 34 and 35: Twitter>The Novel? @tejucole>Teju C

- Page 36 and 37: Twitter>The Novel? @tejucole>Teju C

- Page 38 and 39: Twitter>The Novel? @tejucole>Teju C

- Page 40 and 41: Twitter>The Novel? @tejucole>Teju C

- Page 42 and 43: Twitter>The Novel? @tejucole>Teju C

- Page 44 and 45: Germaine Greer: A Portrait Ben Quil

- Page 46 and 47: Germaine Greer: A Portrait Ben Quil

- Page 48 and 49: Letter to Tom Collins Anna Heyward

- Page 50 and 51: Letter to Tom Collins Anna Heyward

<strong>Contents</strong><br />

3 Editorial by Sally Heath<br />

6 Perspectives with Nicolas Paulin,<br />

Josephine Rowe, David Mence and<br />

Michelle Law<br />

Meanjin Papers (follows p. 16)<br />

Beg by Suzy Freeman-Greene<br />

Essays<br />

18 Debbie Mortimer and the Forensic<br />

Fight by Lorin Clarke<br />

34 Twitter>The Novel? @tejucole>Teju<br />

Cole? by Sam Twyford-Moore<br />

43 Germaine Greer: A Portrait by Ben<br />

Quilty<br />

47 Letter to Tom Collins by Anna<br />

Heyward<br />

60 Share Houses by Lyndal Walker<br />

70 Another Year, Another Engrossing<br />

Crop by Martin Langford<br />

82 The Bartender and the Archive<br />

by Chad Parkhill<br />

Fiction<br />

90 Keilor Cranium by Wayne<br />

Macauley<br />

98 Titty Anne and the Very, Very Hairy<br />

Man by Margo Lanagan<br />

108 The Late Visit by Antonia Pont<br />

117 The Googly by Kevin Brophy<br />

123 Eat. Shit. Die. by Helen Gildfind<br />

133 My Last Birthday by Mark Dapin<br />

139 I should be so lucky by Sam Cooney<br />

Gallery<br />

168 Warwick Baker<br />

Memoir<br />

148 In Search of García Márquez by<br />

Judith White<br />

158 Dinosaurs of the Croatian Wild<br />

by Ronnie Scott<br />

178 There is no hereafter by Paul<br />

Williams<br />

183 Childhood among Strangers by<br />

Linda Judge<br />

Poetry<br />

16 Borroloola Blue by Phillip Hall<br />

32 A World that Could Be Read;<br />

A Winter’s Tale by Diana Bridge<br />

56 Translating a ‘Prolog’ by Jean Kent<br />

58 The Great Poet’s Gene by Alan Gould<br />

68 Farmstay by Sue Ogle<br />

80 Larvatus Prodeo by Shane<br />

McCauley<br />

81 Grace Notes by Ron Pretty<br />

155 Plato by Jakob Ziguras<br />

156 Second Chance by Marian Waller<br />

165 An Overcast Day in Another Part of<br />

the World by Stuart Cooke<br />

176 Report from Blue Mountains by<br />

David Brooks<br />

177 Catching Fire; or, The Art of Sitting<br />

by Mark Tredinnick<br />

186 Questions for the Dead by Ross<br />

Donlon<br />

188 Contributors<br />

190 Index<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 1 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 2 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Editorial<br />

Sally Heath<br />

Ben Quilty, by Germaine Greer, 2009<br />

ThaT journalism ‘musT shine a lighT inTo dark places’ is an overworked<br />

and unhelpful cliché. Sometimes the work of journalists does not produce<br />

a floodlit exposition of good or evil; instead, it often fixes on the more<br />

intellectually and morally intriguing questions found in the shadows.<br />

At the Melbourne Writers Festival this year, the incomparable David Grann<br />

spoke of this often-overlooked aspect of the work of investigative writers. The<br />

award-winning New Yorker staff writer and author said whenever he begins a<br />

story he doesn’t know what he will find. Nothing is simple or uni-dimensional,<br />

even the ‘facts’ he uncovers are complex, nuanced and ‘theory laden’.<br />

Exposing this deeper truth is the heart of his journalism. ‘Transparency is<br />

important. Readers must know where the information came from. And where<br />

there is doubt, the doubt must remain in the story.’ This, he said, ‘is more<br />

truthful reporting’.<br />

It was timely to hear this from such a brilliant practitioner at a moment<br />

when the Meanjin Papers was struggling with the same issues in a piece you<br />

will find in this issue titled ‘Beg’.<br />

Journalist Suzy Freeman-Greene spent twelve months observing,<br />

investigating and thinking about begging in one of Australia’s large capital<br />

cities. It forced her to observe herself and her city as much as it did her nominal<br />

subjects, the people asking for money. Her language changed when she<br />

spoke to beggars. She found she had no consistent reaction. Their sex, their<br />

supplicant signs, their personal stories influenced her response, as did the<br />

weather, what she was doing and the company she was in. Her uncertainty and<br />

inconsistency—her doubts—are a strength of her story.<br />

As Freeman-Greene writes, her anxieties are not unique or particularly<br />

novel. But her year-long project did make her look anew at the people holding<br />

out a cap, cup or hand; they may be in desperate straits or shysters, but now,<br />

to her, they are no longer invisible. And despite the rational argument that<br />

poverty might best be tackled through other means, Freeman-Greene found<br />

that sometimes, in the more awkward shadows of hard reality, it is good to<br />

give a little.<br />

This year’s Meanjin Dorothy Porter Poetry Award goes to ‘An Overcast Day in<br />

Another Part of the World’ by Stuart Cooke (Meanjin, no. 4, p. 165). Our thanks<br />

to judges Andrea Goldsmith and Kristin Henry. Please go to the Meanjin<br />

website to read the judges’ comments and a list of the three commended poets.<br />

And the newly published Meanjin Anthology can be purchased in bookstores<br />

or via the <strong>MUP</strong> website, .<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 3 6/11/12 9:20 AM<br />

3

Meanjin<br />

Editor<br />

Sally Heath<br />

heath@unimelb.edu.au<br />

Associate Editor<br />

Zora Sanders<br />

zsanders@unimelb.edu.au<br />

Meanjin Assistant<br />

Catherine McInnis<br />

Poetry Editor<br />

Judith Beveridge<br />

Poetry Critic<br />

Martin Langford<br />

Design<br />

Jenny Grigg<br />

www.jennygrigg.com<br />

Typesetting<br />

Patrick Cannon<br />

Copyeditor<br />

Richard McGregor<br />

Proofreaders<br />

Natalie Book, Richard McGregor<br />

Website Designer<br />

Inventive Labs/Golden Grouse<br />

Interns<br />

James Douglas, Jessica Szwarcbord,<br />

Sarah Weston, Elyse Wurm<br />

Patron<br />

Chris Wallace-Crabbe<br />

Editorial Advisory Board<br />

Louise Adler, Alison Croggon, Kate Darian-Smith,<br />

David Gaunt, Richard Glover, Jenny Grigg, Brian Johns,<br />

Hilary McPhee, David Malouf and Lindsay Tanner<br />

Founding Editor<br />

Clem Christesen (1911–2003; editor 1940–74).<br />

Meanjin was founded in 1940. The name, pronounced<br />

mee-an-jin, is derived from an Aboriginal word for the<br />

spike of land on which Brisbane sits. The magazine moved<br />

to Melbourne in 1945 at the invitation of the University<br />

of Melbourne, which continues to be Meanjin’s principal<br />

sponsor. In 2008 Meanjin became an imprint of Melbourne<br />

University Publishing Ltd.<br />

Subscriptions<br />

Contact the Meanjin office or subscribe online<br />

at our website.<br />

Where to find us<br />

Postal address: Meanjin, Level 1, 11–15 Argyle Place,<br />

Carlton, Victoria 3053 Australia<br />

Telephone: (+61 3) 9342 0317<br />

Fax: (+61 3) 9342 0399<br />

Email: meanjin@unimelb.edu.au<br />

Website: www.meanjin.com.au<br />

Twitter: www.twitter.com/Meanjin<br />

Facebook: www.facebook.com/Meanjin<br />

Contributions<br />

Meanjin has converted the full backfile of Meanjin issues<br />

(1940– ) into scanned pages that can be accessed via the<br />

digital publishing house Informit (http://www.informit.com.<br />

au). All creative works, articles and reviews converted to<br />

electronic format will be correctly attributed and will appear<br />

as published. Copyright will remain with the authors, and<br />

the material cannot be further republished without authorial<br />

permission. Meanjin will honour any requests to withdraw<br />

material from electronic publication. If any author does not<br />

wish their work to appear in this format, they should contact<br />

Meanjin immediately and their material will be withdrawn.<br />

Printed and bound by Ligare<br />

Distributed by Random House<br />

Print Post Approved PP341403 0002<br />

AU ISSN 0025-6293<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 4 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Perspectives<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 5 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Perspectives<br />

Game over for Space Junk?<br />

Nicolas Paulin<br />

In 1997 an Oklahoma woman<br />

famously reported being hit by<br />

a piece of falling space junk—that<br />

random collection of leftover parts<br />

from old spacecraft, satellites,<br />

rockets and missiles. She emerged<br />

unharmed, but the incident focused<br />

public attention on the dangers of<br />

what might lie beyond clear blue<br />

skies. While this particular variety<br />

of pollution might be invisible to<br />

the naked eye, thousands of tonnes<br />

of junk (known technically as space<br />

debris or orbital debris) now bob<br />

around above our heads. All of it is<br />

destined to fall back into the Earth’s<br />

atmosphere. While some of the<br />

larger components fall into the sea<br />

or onto land, the vast majority of<br />

debris will burn up harmlessly in<br />

the atmosphere and disintegrate,<br />

meaning that the likelihood of<br />

space junk ever causing bodily<br />

harm to human beings remains<br />

remote. 1 But for the space industry<br />

the risk of collision between space<br />

junk and useful objects is all too<br />

real, threatening the satellite<br />

technologies on which we depend<br />

and endangering space missions.<br />

When even a small particle of junk<br />

hits a working spacecraft, it can<br />

cause extensive damage and even<br />

compromise an entire mission. The<br />

problem is fast turning into a crisis. 2<br />

6<br />

1 When an old US satellite fell to Earth in 2011, NASA put the<br />

chances of it falling on a human at 1 in 3200, while a specific<br />

individual’s odds came out at 1 in 22 trillion. NASA estimates<br />

that one catalogued piece of space junk falls to Earth every<br />

day, mostly into the oceans or sparsely populated regions<br />

such as northern Canada, outback Australia or Siberia.<br />

2 In 2010 President Barack Obama released the United States’<br />

new national space policy, calling for better international<br />

cooperation on space junk tracking and removal. In addition<br />

to the need for more innovative technology, national security<br />

pressures and country-based ownership laws for space junk<br />

are among the biggest hurdles to space junk removal.<br />

Over the past half-century of<br />

space exploration, scientists have<br />

imagined a number of solutions to<br />

clean up the mess—from giant nets to<br />

space sticky tape and purpose-built<br />

garbage collection vessels. None is<br />

operational today, due in large part to<br />

doubts about effectiveness and value<br />

for money. But in 2011 a consortium<br />

of scientists and engineers based<br />

at Mount Stromlo Observatory in<br />

Canberra embarked on a gamechanger<br />

using new high-power laser<br />

and optics technology. If successful,<br />

the work would improve the accuracy<br />

of space debris tracking and clean<br />

up the most harmful layers of space<br />

debris within a decade.<br />

Laser removal of space litter is not<br />

a new idea, but transforming theory<br />

into a marketable technology is a<br />

significant challenge for the space<br />

industry. In the 1990s US scientists<br />

developed the first theories for<br />

removal of space debris using groundbased<br />

lasers. However, the US project<br />

lacked the key technological advances<br />

required in lasers, telescopes,<br />

electronics and adaptive optics (a<br />

key technology used to overcome the<br />

effects of atmospheric air turbulence<br />

on laser beams and thus improve their<br />

focus on a particular target).<br />

Today that technology is ready.<br />

Building on its experience with largescale<br />

international projects including<br />

the Giant Magellan Telescope, the<br />

Research School of Astronomy and<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 6 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Satellite laser ranging from EOS Space<br />

Centre at Mount Stromlo Observatory,<br />

Canberra, photograph by EOS Space<br />

Systems, 2011<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 7 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Perspectives<br />

Astrophysics (RSAA) at the Australian<br />

National University has established<br />

a specialty in adaptive optics and has<br />

been busy attracting key international<br />

specialists in the process. In early 2011<br />

the RSAA teamed with a commercial<br />

telescope and satellite tracking<br />

company, Electro Optic Systems<br />

(EOS), which was keen to develop a<br />

commercially viable and cost-effective<br />

industrial prototype for tracking<br />

and removing space debris. Using<br />

this new-generation technology, the<br />

consortium is building an instrument<br />

that will locate space junk with a high<br />

level of accuracy. The second phase of<br />

development will test whether highpower<br />

lasers are capable of nudging<br />

debris out of its orbit and back into<br />

the Earth’s atmosphere to combust.<br />

A test model is now in construction<br />

at the Mount Stromlo Observatory,<br />

housed in one of EOS’s large<br />

telescopes. Operational testing on real<br />

space junk is expected to begin by the<br />

end of 2013. If the tests are successful,<br />

Australia could become the first<br />

country to develop a commercially<br />

viable system for space junk removal.<br />

It is no coincidence that the<br />

project targets space junk removal at<br />

low Earth orbit (LEO) and where the<br />

most harmful mass of space junk is<br />

concentrated. Five decades of space<br />

exploration and an unfortunate<br />

series of missile tests and space<br />

accidents in recent years 3 have<br />

created a chain reaction of collisions,<br />

8<br />

3 These events include a 2007 Chinese anti-satellite missile<br />

test, US destruction in 2008 of a defective spy satellite and<br />

a 2009 collision between a defunct Russian satellite and a<br />

working US satellite.<br />

creating an escalating number of<br />

components. The North American<br />

Defence Command, which maintains<br />

the oldest database of space debris,<br />

estimates that there are now 25,000<br />

components of space junk more than<br />

10 centimetres wide (the threshold<br />

for tracking). Of these, it is able to<br />

track only 8000 components, leaving<br />

a high potential for unpredictable<br />

collision. For working spacecraft<br />

obliged to orbit in LEO—such as the<br />

International Space Station, Earth<br />

observation and communication<br />

satellites—damage from small-scale<br />

projectiles is a constant risk, while the<br />

possibility of collision with any debris<br />

more than 10 centimetres wide calls<br />

for full alert and a change of course.<br />

So can Australia claim a world first<br />

in cleaning up the universe? Perhaps<br />

not yet, but watch this space …<br />

International Writing Program,<br />

Iowa City<br />

Josephine Rowe<br />

arrive to languid late summer,<br />

I the Hollywood promise of tall<br />

cornfields, weathered red barns.<br />

Harvest time. Within two hours<br />

of touching down I’m tramping<br />

jet-lagged around the woodlands of<br />

Redbird Farms with my fellow writers:<br />

a kind of get-to-know-you hike,<br />

which precedes the get-to-know-you<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 8 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Perspectives<br />

dinners and the get-to-know-you<br />

parties. We introduce ourselves with<br />

full names and nationalities: Hi, I’m<br />

Bina Shah from Pakistan; I’m Hind<br />

Shoufani from Palestine.<br />

I’m discussing various definitions<br />

of the word ‘tame’ with Moshe Sakal<br />

( from Israel) when I accidentally tread<br />

on a snake. It’s gone almost before<br />

I realise, and I take a baffled little<br />

breath as it disappears.<br />

She didn’t even scream, says<br />

Moshe, as the others catch up. Well,<br />

she’s Australian, someone answers.<br />

The program’s director clinches it<br />

with a story about Gail Jones, who<br />

purportedly spent her childhood<br />

lifting snakes by their tails and<br />

whacking their heads against tree<br />

trunks. I don’t know whether the story<br />

is true, but it doesn’t matter, the die is<br />

cast. Australia: a nation of nonchalant<br />

snake killers.<br />

There are thirty-seven of us,<br />

from thirty-five countries. I am the<br />

youngest. Lynley Hood, from New<br />

Zealand, is the oldest. Zhang Yueran,<br />

from China, is the best selling. But it’s<br />

China, she says dismissively. There<br />

are so many people. Jeremy Tiang,<br />

from Singapore, is the most patient<br />

and the most sharply dressed, always.<br />

We are split between two hotels.<br />

There is the Sheraton, which is like<br />

Sheratons the world over, and there<br />

is Iowa House. Iowa House is dated,<br />

dorm-like. There is a lot of wood-grain<br />

veneer. But my room has a bath, a<br />

desk and a picturesque view of the<br />

Iowa River, a view that becomes more<br />

so as summer ambles into spectacular<br />

Midwestern fall. More importantly,<br />

Iowa House is where Raymond<br />

Carver lived in 1973, the year he and<br />

John Cheever taught at the Writers’<br />

Workshop and drank mercilessly in<br />

Cheever’s room, up on the fourth<br />

floor. Carver lived on the second floor<br />

(our floor) but Cheever never came<br />

down because he was, apparently,<br />

afraid of being mugged in the hallway.<br />

The second-floor hallway has soft<br />

carpet and cream walls decorated<br />

with framed prints of non-challenging<br />

art works. It’s difficult to imagine<br />

it feeling threatening; to me it feels<br />

share-housey, raucous. Somebody is<br />

always awake. Something is always<br />

happening, or about to happen.<br />

Urgent calls on the room to room:<br />

Can you come take a look at my neck?<br />

Can you tell me what I did last night?<br />

I’m okay, I just can’t stand up.<br />

One night X falls asleep in the bath<br />

and floods her hotel room. It isn’t<br />

until the water trickles through to<br />

the first floor that reception rushes<br />

up to unlock the door and lift her<br />

from the overflowing bath. For weeks<br />

afterwards the hallway is lined with<br />

industrial fans, drawing moisture<br />

from air and carpet. Every now and<br />

again someone opens their door<br />

and yells at the fans: I’m trying to<br />

fucking work! Somehow the work<br />

gets done despite the fans. Books are<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 9 6/11/12 9:20 AM<br />

9

Perspectives<br />

researched and translated. Lectures<br />

are written and delivered. YouTube<br />

links to literal video versions of Tears<br />

for Fears songs are widely dispersed,<br />

and untranslatable concepts are<br />

collectively stewed over.<br />

I shape my writing day around<br />

the power plant whistle, which is as<br />

much a part of the ambience as the<br />

industrial fans and the badly wired<br />

fire alarm. But I have a soft spot for<br />

the power plant whistle. It makes<br />

a lonesome, sorrowful noise, like<br />

Bradbury’s fog horn, like a great<br />

mournful whale drifting up the Iowa<br />

River. It blasts several times a day:<br />

morning, lunchtime and end of shift.<br />

At the end-of-shift whistle I close<br />

my laptop and go out to meet the<br />

others at the Mill or Martini’s or the<br />

Fox Head. The bartenders at the Fox<br />

Head are mostly PhD candidates in<br />

philosophy, with impressive facial<br />

hair and loose elbows that make for<br />

generous pours. When I ask for a<br />

glass of tequila and soda I get a glass<br />

of tequila, soda sprinkled over it like<br />

bitters. The jukebox has a great Sam<br />

Cooke selection, and Kevin Bloom,<br />

the gruff South African journalist,<br />

spends a good portion of his per<br />

diem feeding it quarters, playing ‘A<br />

Change Is Gonna Come’. And in this<br />

dimly lit, wood-panelled microcosm,<br />

it’s easy to believe that perhaps it<br />

will. Israel and Palestine are deep<br />

in conversation that steers deftly<br />

away from settlements and two-state<br />

10<br />

solutions. A blind man at the bar<br />

is asking Kevin about apartheid,<br />

listening intently before saying,<br />

‘You’ll have to tell me, because I can’t<br />

tell from your voice. Are you white or<br />

are you black?’<br />

I turn twenty-seven here, dance<br />

around the pool table to Songs: Ohia.<br />

Then everything speeds up. November<br />

comes as a kind of ground rush. Each<br />

morning I stalk up the west lawn<br />

towards the Old Capitol building, my<br />

hair rustling a susurrus in the cold,<br />

as though the trees are shaking their<br />

branches in my ears. Each morning I<br />

wear more layers, watch the squirrels<br />

gather their winter stores with<br />

greater urgency. I should be closing<br />

my account and returning all those<br />

library books.<br />

The Israelis get married on the first<br />

of November. Tel Aviv, gay-friendly<br />

as it is, doesn’t allow same-sex<br />

marriages. Remarkably, Iowa does.<br />

Few of us know the words to ‘Hava<br />

Nagila’, but everybody knows when to<br />

shout Hey! and we do so with verve,<br />

raising Moshe and Dory up on white<br />

dining chairs, Hind contributing<br />

impressive ululations. In a few weeks<br />

Moshe will be excluded from a literary<br />

panel at a festival in Marseilles, at<br />

the request of a Palestinian poet.<br />

We will read news of this, back in our<br />

respective home countries, and it will<br />

affirm what we knew all along: our<br />

little world was not representative of<br />

the larger one.<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 10 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Perspectives<br />

What did we say to each other,<br />

that last night in the Fox Head,<br />

raising our glasses in moments we<br />

won’t remember? The untranslatable<br />

concepts remain untranslatable. But<br />

we worked at it during those three<br />

months. We got as close as we could.<br />

Cooking for Edward Albee<br />

David Mence<br />

In 2011, as the lucky recipient of<br />

Inscription’s Edward F. Albee<br />

Scholarship, I got to spend a month<br />

researching and writing my play<br />

Entanglement (about the Large<br />

Hadron Collider and the hunt for the<br />

so-called God particle) in Montauk,<br />

New York.<br />

Montauk is roughly three and a<br />

half hours from New York City via<br />

the Long Island Rail Road (familiar<br />

to fans of Eternal Sunshine of the<br />

Spotless Mind). A sleepy little fishing<br />

town perched at the tip of Long<br />

Island, Montauk is home to the<br />

William Flanagan Memorial Creative<br />

Persons Center (‘the Barn’), which<br />

Edward Albee established in 1967<br />

with the proceeds from his play Who’s<br />

Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The Barn<br />

is, as its name suggests, a big New<br />

England–style whitewashed barn<br />

that once served as a stable for the<br />

nearby Montauk Manor (brainchild<br />

of the Gatsbyesque millionaire Carl<br />

Fisher, it opened in 1927 and is still<br />

going strong). These days, the Barn<br />

stables writers and visual artists<br />

and provides them with time and<br />

splendid isolation. Albee generally<br />

keeps a low profile and makes a few<br />

brief, mysterious appearances that<br />

the fellows are left to decipher. Albee<br />

has a droopy snow-white moustache,<br />

a cheeky boyish grin and penetrating<br />

blue eyes and is as sharp as a whip<br />

at eighty-three. He also has a way of<br />

peering down his nose at you as he<br />

listens, which makes you feel small<br />

even though he is, in all probability,<br />

far shorter than you are.<br />

It was over a week before any<br />

of us encountered our host. One of<br />

the writers, hunched over a bowl<br />

of porridge, looked up to see Albee<br />

depositing a handful of mail on the<br />

kitchen bench. ‘Nothing for you,’ he<br />

drawled, ‘better luck next time.’ We<br />

puzzled over this cryptic utterance:<br />

was he referring to the mail, our<br />

creative fortunes, or life in general?<br />

Such simplicity, we decided, from<br />

one of the world’s great masters of<br />

dialogue, must belie hidden depths.<br />

We looked for guidance in Albee’s vast<br />

library (we re-read a number of his<br />

plays) and his formidable collection<br />

of classical LPs (complete recordings<br />

of von Karajan, Rubinstein, Gould)<br />

and yet, rather like a crack squad of<br />

biographers tasked with the life of<br />

Shakespeare, we were merely filling<br />

an evidentiary vacuum with ideas,<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 11 6/11/12 9:20 AM<br />

11

Perspectives<br />

fabrications and conspiracies of our<br />

own making. This palpable absence<br />

soon gave rise to a mild paranoia: it<br />

was absurd, but at times we felt as<br />

though we were being watched (or<br />

watched over), as if America’s greatest<br />

living playwright could give a damn<br />

what we did with our time.<br />

Then came our second encounter.<br />

One of the visual artists was sitting<br />

out the front of the Barn reading a<br />

book when Albee’s moustachioed<br />

face materialised above his page and<br />

said something like, ‘Keep working.’<br />

This again raised a problem for<br />

interpretation: had he meant ‘keep<br />

up the good work’ or more ominously<br />

‘get back to work’? In the face of such<br />

hermeneutic fear and trembling, all<br />

we could do was redouble our artistic<br />

efforts; the visual artist in question<br />

even began to work through the<br />

night. Yet even this was no match<br />

for the sixteen-hour days that,<br />

according to local legend, the Soviet<br />

exile Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn had<br />

worked when he first arrived in New<br />

England. Let alone Albee himself, who<br />

informed us that he was making good<br />

progress on his new play, while some<br />

of us, less than a third his age, were<br />

floundering beneath a sea of false<br />

starts, incoherent storyboards and<br />

poorly executed ideas.<br />

All which may help to explain<br />

why I felt such an overwhelming<br />

desire to cast myself into the Atlantic<br />

Ocean when informed that Albee had<br />

12<br />

decided to come over for dinner …<br />

and I had been nominated head chef.<br />

After hyperventilating into a bag<br />

for a few minutes, I jumped on the<br />

pushbike with the broken pedal and<br />

rushed down to the docks to catch<br />

the fishmonger before close. He had<br />

two bags of mussels left, which was a<br />

stroke of good luck, because mussels<br />

are one of the few things I know how<br />

to cook. Back at the Barn, the mussels<br />

stewed happily in tomato, white<br />

wine, chilli and herbs. There were an<br />

awful lot of them—enough to feed ten<br />

people—so they had to be steamed<br />

in a giant pot. Meanwhile, two<br />

sous-chefs prepared such essential<br />

items as roast potato gratin, sautéed<br />

kale, avocado salad and, for dessert,<br />

apple pie and vanilla ice cream.<br />

Albee arrived at around 7 pm.<br />

Given what a warm, balmy night it<br />

was, he decided we ought to dine<br />

al fresco at the big wooden table.<br />

Luckily, he likes mussels, and took<br />

great pleasure in cracking them and<br />

sucking the gravy out of their shells.<br />

Everything was going according to<br />

plan. But then Albee turned to me<br />

and growled, ‘This one’s not open.’<br />

He popped the offending mussel on<br />

the edge of my plate. Grinning like<br />

an idiot, I picked up the shiny little<br />

shellfish and proceeded to bash it on<br />

the side of the table. ‘No, no,’ he said,<br />

‘don’t do that!’ I sheepishly put it back<br />

and smiled, and he smiled, and said,<br />

‘Some of them want to stay closed.’<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 12 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Perspectives<br />

Leaving<br />

Michelle Law<br />

Mum pulls the ancient songbook<br />

from one of the rubbish bags,<br />

rests a heavy palm on its faded cover<br />

and sighs. The book’s spine is shot,<br />

the pages yellowed. Mum handles this<br />

book with care, periodically taping<br />

and gluing it together. This is done<br />

chiefly to preserve the memory of its<br />

original owner, Jimmy, my youngest<br />

uncle, who killed himself after being<br />

deported from Australia.<br />

We had arrived at Mum’s that<br />

day wearing our grubbiest clothes,<br />

clutching buckets and bags<br />

overflowing with cleaning gear. My<br />

sister Candy had stocked up on gloves<br />

and masks, and my brother Ben had<br />

brought his vacuum cleaner to inhale<br />

the cockroach corpses lying beneath<br />

the couch. Mum had been living in our<br />

childhood home for more than twenty<br />

years, but with the five of us children<br />

long gone, she’d decided to move.<br />

We knew that the process was<br />

going to be arduous because Mum<br />

never threw anything out. Everything<br />

was significant to her; everything had<br />

value—from a rusty pair of gardening<br />

shears (‘They still cut, don’t they?’)<br />

to an unopened calendar from 1999<br />

(‘Some child can make craft out of it’).<br />

If it once had monetary or sentimental<br />

worth, it stayed.<br />

As everyone set to work trashing<br />

outdated newspapers and lobbing<br />

VHS tapes into the skip bag stationed<br />

in the yard, I sat with Mum in the<br />

kitchen, nursing a glass of water.<br />

‘Only you understand how I feel, Mic,’<br />

she said, the book between us on the<br />

dining table.<br />

Living alone with Mum for<br />

seventeen years, I’d learnt to see<br />

how useless objects could become<br />

steeped in symbolism, to the point<br />

where parting with them becomes<br />

excruciating. When I donated a box<br />

of my favourite toys to Lifeline, I<br />

shoved them into the container and<br />

disappeared without a word to the<br />

other side of the house where I could<br />

cry without being heard. I didn’t want<br />

to be on Mum’s side. I didn’t want to<br />

be weak.<br />

Mum’s book was a tome of<br />

Western pop songs that she had<br />

carried with her when she’d migrated<br />

from Malaysia to Hong Kong, and<br />

then from Hong Kong to the Sunshine<br />

Coast. When on the weekends my<br />

sister Tammy swapped from Dad’s<br />

house to Mum’s, the two of us would<br />

lie on the carpet at night with the<br />

ceiling fan whirring, and sooner or<br />

later Mum would enter the living<br />

room with the book clasped reverently<br />

in two hands.<br />

‘Any requests?’ she would ask.<br />

Tammy would lean back on the<br />

makeshift bed she’d constructed from<br />

cushions and bed sheets and close her<br />

eyes. ‘ “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the<br />

Ole Oak Tree” or “Que Será Será”.’<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 13 6/11/12 9:20 AM<br />

13

Perspectives<br />

‘How about both?’ Mum would<br />

flick through the yellowed pages<br />

and open the book to our dog-eared<br />

favourites. As Tammy drifted off to<br />

the sound of Mum’s singing, I’d stare<br />

at the ceiling and think about the<br />

morning, when Dad would swing by<br />

in his Honda and Mum and I would<br />

be alone again.<br />

Jimmy was the seventh and<br />

youngest child in Mum’s family. Mum,<br />

the sixth, and her sister Judy, the<br />

fourth, had arrived in Australia in the<br />

1970s. Both women were newlyweds<br />

who had fled with their husbands<br />

amid fear of Hong Kong’s handover<br />

from British to Chinese rule. Dad had<br />

relatives living in Sydney who assured<br />

him that Australia had a better quality<br />

of life than China. There was space in<br />

Australia, and the people were free.<br />

It was the perfect country to raise<br />

a family. After Mum’s move, most<br />

of her siblings, including Jimmy,<br />

followed suit.<br />

Within a few years, Mum’s siblings<br />

had established themselves on the<br />

Sunshine Coast. Their children were<br />

enrolled at the local school, and<br />

they’d made friends with the regulars<br />

who frequented their restaurants.<br />

But soon the authorities were tipped<br />

off, and they were arrested for<br />

overstaying their tourist visas. After<br />

a brief stint in Villawood, Mum’s<br />

siblings were sent back to Hong<br />

Kong with nothing to their names.<br />

Everything they owned was left with<br />

14<br />

us, stowed away in all the empty<br />

corners of the house.<br />

On the third straight day of<br />

packing, Tammy and I stood in the<br />

garage with Mum, deciding what to do<br />

with the contents of a dusty cardboard<br />

box. Mum was deliberating over<br />

which objects to keep, donate, sell or<br />

throw out. She held up a mouldy soft<br />

toy that had belonged to one of her<br />

nephews and considered it in silence.<br />

Then, after a spell, she placed it in the<br />

mounting ‘keep’ box, alongside the six<br />

other mouldy toys already in there.<br />

Right then I felt with a burning<br />

clarity how lucky I was. How my<br />

parents had sacrificed their own<br />

relationships and ambitions for<br />

me to have a future. How Mum had<br />

allowed her first family to be torn<br />

apart in order for ours to remain<br />

together. How my only real pressing<br />

responsibility now was to lead a happy<br />

life for her sake, and how it was nearly<br />

impossible for me to feel carefree if<br />

she was unhappy.<br />

‘Mum,’ said Tammy firmly. ‘You<br />

can’t fit all this stuff in an apartment<br />

in Brisbane. And we still have about<br />

ten other rooms to pack.’<br />

Mum threw the toy down in a<br />

sudden rage and held her arms stiffly<br />

by her sides. ‘You’re all rushing me!’<br />

she said. ‘Can’t you understand I can<br />

do this myself?’<br />

I stood back and watched Tammy<br />

berate Mum for being irrational.<br />

Growing up with Mum, I’d learnt<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 14 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Perspectives<br />

never to speak back to her, to save<br />

myself a fight. But on this occasion<br />

Tammy received the full brunt of<br />

Mum’s fury and, worst of all, her grief.<br />

By the end of their spat, Tammy was<br />

sobbing. I stood in the background<br />

wringing my hands, unsettled at<br />

seeing an older sibling so helpless.<br />

Mum was unresponsive to her display,<br />

being too immersed in her own<br />

anguish to comprehend Tammy’s.<br />

At some stage a neighbour crossed<br />

the road to ask if everything was<br />

okay. Nobody responded; we were<br />

all speechless. Eventually Tammy<br />

croaked something and the neighbour<br />

left. When we were alone again, Mum<br />

let us have it.<br />

‘These aren’t yours, so don’t<br />

touch them,’ she said in Cantonese,<br />

gathering the toys up in her arms.<br />

‘You’re all spoiled, selfish Australian<br />

kids who don’t understand the true<br />

worth of things.’ She brought up the<br />

events of the previous day, when<br />

we had unknowingly thrown out a<br />

teapot filled with buttons that she’d<br />

cut off clothes that had belonged to<br />

Jimmy. She said that we were killing<br />

her, that if we kept disrespecting<br />

our mother our grandmother would<br />

haunt us.<br />

We packed a cooler bag and headed<br />

to the local park to give Mum space.<br />

Tammy was sniffling during the car<br />

ride there and none of us knew what<br />

we could say to offer comfort. At the<br />

park we found a soft patch of grass in<br />

the shade that wasn’t infested with<br />

ants and set down our lunch supplies<br />

of bread and soft drink. Everyone ate<br />

in silence. It made me uneasy; usually<br />

when we ate together we talked over<br />

each other at the dinner table, with<br />

everyone straining to get a word in.<br />

Then, to break the tension,<br />

someone farted and we all burst<br />

out laughing. Candy curled her arm<br />

around Tammy, who still hadn’t<br />

said a word. Tammy relaxed into<br />

her shoulder. We each dug our toes<br />

into the impossibly green grass<br />

and shielded our eyes against the<br />

glare reflecting off the nearby lake,<br />

where some kids on waterskis were<br />

shrieking. On the pavement a young<br />

girl rattled past on her scooter, calling<br />

for her parents to catch up. They<br />

were ambling close behind in their<br />

thongs, licking ice creams and smiling<br />

benignly. A warm breeze lifted the<br />

curls in the mother’s hair and she<br />

gently slung them back across her<br />

shoulder. We gnawed on our bread<br />

rolls, quietly admiring these scenes<br />

from a distance. When Andrew<br />

received a phone call from Mum,<br />

we packed up our spread and left. M<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 15 6/11/12 9:20 AM<br />

15

Borroloola Blue<br />

Phillip Hall<br />

All around our steel home’s broad bull-nosed verandah<br />

we’d jack-hammered rock, dug garden beds and ponds,<br />

fenced an oasis as we planned for shade, blossoms, wildlife and fruit.<br />

Among the natives we’d cultivated<br />

paw paws, frangipanis, mangos, bananas .... Security<br />

lights drew tree frogs and geckos; a Greek chorus<br />

of bellowed crawks and clicking chick chacks;<br />

an agile profusion alternating with contentment and strife.<br />

But that season, in the Build-up to the Wet,<br />

it was the raucous rocket frogs’ ratchet-like croakings<br />

we noticed most. Each night the males made our ponds<br />

throb with their rapid yapping calls, withdrawing at sunrise<br />

when grass finches postured on the lips of ponds,<br />

flicking their tails and singing a series<br />

of squeezed rasping notes; white-gaped honeyeaters<br />

threaded a path through foliage and blossom<br />

as Papuan cuckoo-shrikes tore paw paws and mangos.<br />

Then one night at the Build-up’s end, as we drank<br />

chardonnay on ice, Yanyula youths ran amok<br />

on ganja, throwing stones and shiaking at our padlocked gates.<br />

It only ended when [sorry name] leapt on our fence,<br />

screaming at stars, before lightly climbing<br />

a power pole like a cabbage tree palm—<br />

an unabashed athleticism electrified<br />

16<br />

in the fall.<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 16 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Essays<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 17 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Debbie Mortimer and<br />

the Forensic Fight<br />

Lorin Clarke<br />

The case ThaT overTurned The gillard governmenT’s Malaysia<br />

solution in August 2011 set the ball rolling in a chain of political events, the<br />

repercussions of which are still being felt. Debbie Mortimer SC was part of<br />

a team of barristers in that case who represented the asylum seekers. For<br />

Mortimer, the unflappable New Zealander who worked with the other lawyers<br />

on the case without expectation of a fee, this was a matter of principle. The<br />

principle for her was that the rule of law should always be upheld. Many<br />

Australians don’t know what the rule of law is, let alone how it might be upheld,<br />

or perhaps even why it should be upheld.<br />

This is partly because the debate on issues of national importance is often<br />

dominated not by those best qualified, with the best information, but by the<br />

media conducting a slanging match with politicians in a time frame that<br />

best suits the news cycle. And the justification for this is that Australia is a<br />

democracy. Before embarking on a discussion of Mortimer’s contribution, it is<br />

instructive to revisit George Megalogenis’s perceptive analysis of the political<br />

climate in the lead-up to the case.<br />

The wrong conversation<br />

In his 2010 Quarterly Essay, ‘Trivial Pursuit’, Megalogenis paints a depressing<br />

picture of the co-dependence between politics and the media in contemporary<br />

Australia. Two years on, the minority government is still in office, with the<br />

support of crossbenchers, despite a leadership challenge and investigations<br />

into the behaviour of several members of parliament. The two most unpopular<br />

institutions in the country are the federal parliament and the media. This is<br />

partly to do with what Megalogenis calls ‘medium creep’, where the media<br />

have been allowed to run the agenda. ‘There is a collective loss of confidence<br />

at work here,’ says Megalogenis. ‘No one is really sure what voters will say to a<br />

new idea, so government and media ask them first through focus groups. It is<br />

no way to run a national conversation.’ 1 Megalogenis argues that under the<br />

leadership of prime ministers Bob Hawke and then Paul Keating, bold, often<br />

unpopular reform was introduced, which led directly to positive social change.<br />

He urges similar action now. ‘No nation should be so lucky that it delays<br />

reform indefinitely without suffering any consequences,’ he says. 2 The end of<br />

Megalogenis’s essay is perhaps the most disheartening part. Describing the<br />

political culture as ‘both polarised and disengaged’, he claims Australia needs<br />

to relearn how to have a political discussion about how and why to change and<br />

develop as a society. ‘Before they can re-educate the electorate’, he says, ‘they<br />

must first re-train themselves.’ 3 This is all very well, but what do we do in the<br />

18<br />

1 George Megalogenis, ‘Trivial Pursuit:<br />

Leadership at the End of the Reform<br />

Era’, Quarterly Essay, no. 40 (2010),<br />

p. 15.<br />

2 Megalogenis, ‘Trivial Pursuit’, p. 43.<br />

3 Megalogenis, ‘Trivial Pursuit’, p. 80.<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 18 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Debbie Mortimer, photograph by<br />

Mark Chew, 2012<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 19 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Debbie Mortimer and the Forensic Fight Lorin Clarke<br />

meantime? If the news media and the people who represent us in parliament<br />

won’t lead a mature, constructive conversation about what kind of society we<br />

want to be, who will?<br />

Several months after the release of Megalogenis’s essay, Debbie Mortimer<br />

touched on these ideas at an event in Melbourne addressing the prospect of<br />

a bill of rights in Australian law. The event was a Wheeler Centre panel on<br />

human rights as part of Law Week. Mortimer paused on the topic of politicians<br />

pandering to the media machine. ‘It’s interesting to talk about whether<br />

it’s political cowardice or whether it’s a political recognition of a lack of<br />

support in the Australian community,’ she said. ‘They’re not the same thing.’<br />

Contemplating the kind of reform necessary to incorporate a bill of rights into<br />

federal law, Mortimer said, ‘You can do it either through leadership that is<br />

speaking ahead of the community and takes the community with them or you<br />

can talk about recognising that it’s a political move that the community wants.’<br />

Australians, she pointed out, are not marching in the streets over human rights<br />

issues. Like Megalogenis, though, Mortimer held the media partly to blame for<br />

the recent lack of political leadership:<br />

20<br />

4 Debbie Mortimer, ‘Injustice<br />

anywhere: Human Rights in Practice’,<br />

discussion with Alan Attwood, Robert<br />

Stary and Julian Burnside, Wheeler<br />

Centre, 16 May 2011.<br />

5 David Marr, ‘How did this boat get so<br />

close to the coast?’, National Times, 16<br />

December 2010.<br />

It’s the minute you disengage people from that immediate<br />

connection [with the actual people involved] that you enable this<br />

general prejudice, and it doesn’t matter whether you’re talking about<br />

boat people, it doesn’t matter whether you’re talking about same-sex<br />

attracted people—the minute you disengage from that personal<br />

connection, you allow stereotyping to get in. 4<br />

The contention that the ‘polarised and disengaged’ Australian public<br />

has come to distrust change and resent difference prompts the question:<br />

are we just a bunch of reactionaries? For Mortimer, it’s not as simple as that.<br />

In December 2010, Christmas Island locals awoke in the night to a maritime<br />

disaster on their shores. A boat had crashed off the rocks, killing at least<br />

half the asylum seekers on board. 5 The locals, scrambling to help in the<br />

rescue effort, might not have been in favour of allowing asylum seekers into<br />

Australia for processing. They might even have supported Opposition Leader<br />

Tony Abbott’s stated intention to ‘turn back the boats’. That night, though, the<br />

nuances of the political debate were cast aside. That’s because, says Mortimer,<br />

‘Australians are good-hearted people. And what they’re then seeing right in<br />

front of their eyes is another human being in trouble and Australians have no<br />

difficulty responding to that.’<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 20 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Essays<br />

6 Madonna King, interview with<br />

Prime Minister Julia Gillard, ABC<br />

Radio, Brisbane, 2 September 2011.<br />

7 Transcript: Prime Minister Julia<br />

Gillard and Minister Chris Bowen, joint<br />

press conference, 7 May 2011.<br />

8 For every asylum seeker sent to<br />

Malaysia under the scheme, Australia<br />

would accept five processed refugees<br />

from Malaysia, increasing Australia’s<br />

refugee intake by 4000 over four years.<br />

9 Gillard and Bowen, press conference.<br />

10 Enda Curran, ‘Support for<br />

Australian government hits<br />

record low’, Wall Street Journal’s<br />

‘MarketWatch’, 11 July 2011.<br />

11 James Massola, ‘Pressure grows<br />

on Gillard’s leadership’, Australian,<br />

2 September 2011.<br />

12 Matt Johnston, ‘Gillard sunk as<br />

people smugglers cash in on Malaysia<br />

deal’, Herald Sun, 1 September 2011.<br />

What Debbie Mortimer does in the courtroom can be viewed as a systematic<br />

attempt to show Australians the effect of Australian policies on the ‘people<br />

on the margins’. Mortimer’s work as a barrister calls the decision-makers to<br />

account and demonstrates to the public that there are laws designed to protect<br />

them from the kind of abuses of power that can happen when nobody is paying<br />

attention. The media are not the court. The government is not above the<br />

law. And the public, in whose name this circus has been constructed, have a<br />

responsibility too. By drawing our attention to the laws that are being enacted<br />

in our name, Debbie Mortimer indirectly challenges Australians to engage in<br />

a ‘national conversation’ about how we treat the less fortunate members of<br />

Australian society.<br />

The Malaysia case<br />

On 2 September 2011 Australia’s Prime Minister was deflecting what she called<br />

‘fevered speculation’ about her ability to run the country. 6 At issue was the six<br />

to one High Court decision handed down on 31 August that declared invalid<br />

the government’s ‘Malaysia people swap’ deal. This was the deal that had,<br />

only months earlier, been hailed by the government as a triumph of regional<br />

diplomacy in defiance of opportunistic people smugglers. The purpose of the<br />

agreement, according to the government, was to ‘break the people smugglers’<br />

business model’ by sending to Malaysia for processing all asylum seekers who<br />

arrive in Australian territory by boat—placing them ‘at the back of the queue’. 7<br />

In exchange, Australia would take on additional refugees from Malaysia. 8 The<br />

government framed the deal as a clear message to any potential asylum seekers<br />

who saw Australia as a safe haven: ‘From today onwards—fair warning—you do<br />

not have a guarantee of being processed and resettled in Australia.’ 9 According<br />

to the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship, Chris Bowen, the deal was<br />

established ‘on very strong legal grounds’. On the contrary, the High Court<br />

found that Bowen did not have the power to decide to send asylum seekers to<br />

Malaysia. The agreement between Australia and Malaysia was not worth the<br />

paper it was written on.<br />

Midway through 2011, just before the High Court brought down its<br />

decision, support for the government had been, according to Newspoll, at an<br />

all-time low. 10 Now the subeditors were beside themselves. ‘Pressure grows<br />

on Gillard’s leadership,’ screamed the headlines. 11 Melbourne’s Herald Sun<br />

ran with ‘Gillard sunk’. 12 On the ABC’s 7.30 program, reporter Heather Ewart<br />

indicated that dissatisfaction within the ALP ran deep. ‘Talk to anyone in Labor<br />

ranks today, including senior levels of government, and behind the scenes<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 21 6/11/12 9:20 AM<br />

21

Debbie Mortimer and the Forensic Fight Lorin Clarke<br />

13 Heather Ewart, report, ‘Beginning<br />

of the end?’, ABC TV, 7.30, 1 September<br />

2011.<br />

14 Graham Richardson, Radio 3AW,<br />

1 September 2011. Quoted in Ewart,<br />

‘Beginning of the end?’.<br />

15 Gillard and Bowen, press conference.<br />

16 Malcolm Farr, ‘Blaming the ref:<br />

Julia Gillard attacks High Court<br />

they’re all saying the same thing: that the High Court decision is diabolical<br />

for Labor, compounding a now entrenched public perception of government<br />

incompetence.’ 13 When asked in a radio interview whether it was too late for<br />

Julia Gillard to save herself from certain electoral doom after the High Court<br />

decision, former ALP minister Graham Richardson said simply: ‘Oh, yeah,<br />

way too late. There’s no way she can turn this around.’ 14 The Prime Minister<br />

and Minister Bowen, in response to the court’s decision, called a joint press<br />

conference. ‘The easy option’, said Bowen, ‘would be to resign.’ 15<br />

He did not resign. He and the Prime Minister, both clearly irritated, held<br />

firm. The Prime Minister was defiant, issuing a ‘blistering attack’ on the High<br />

Court. 16 Convention dictates that the executive arm of government in Australia<br />

refrain from commenting on the findings of the judiciary, so as to protect the<br />

independence of the courts in what is a system of responsible government.<br />

Extraordinarily, the Prime Minister not only criticised the court, saying it had<br />

‘basically turn[ed] on its head the understanding of the law’, she characterised<br />

the judgment of the Chief Justice, Robert French, as inconsistent. She declared:<br />

‘His Honour Mr Justice French considered comparable legal questions when<br />

he was a judge of the Federal Court and made different decisions to the one<br />

that the High Court made yesterday.’ 17 Gillard was accusing the chief justice<br />

of a mischievous creativity designed to achieve a preferred result. Interpreted<br />

by most commentators as a deliberate attack on the integrity of the judiciary,<br />

the Prime Minister’s comments were also, according to most legal experts<br />

(including those sitting on the High Court), incorrect in law. 18<br />

However spurious the government’s claims about the legal merits of the<br />

case, this suggestion that the court was misusing its power took hold in the<br />

media. Parliamentary secretary David Bradbury was quoted as saying, ‘High<br />

Court justices won’t be the ones who have to take phone calls about boats<br />

crashing into rocks on Christmas Island.’ 19 Thus the court was characterised as<br />

simultaneously conniving and naive. The implication was that those sitting on<br />

the High Court (and, by extension, those working on the case for the asylum<br />

seekers) were putting at risk the lives of the very people they were trying<br />

to protect.<br />

The ‘Malaysia case’ started with a text message from human rights lawyer<br />

David Manne to Debbie Mortimer. ‘Just had a call for help,’ it said. ‘Looks<br />

like expulsions planned for Monday.’ 20 Manne had received word through his<br />

contacts that two asylum seekers in detention on the Australian territory of<br />

Christmas Island needed help. A team of barristers worked with instructing<br />

solicitors from Allens Arthur Robinson and David Manne. The clients in<br />

22<br />

judges for scuttling Malaysia Deal’,<br />

, 1 September 2011.<br />

17 Tom Iggulden, report: Gillard<br />

attacks High Court over ruling, ABC<br />

TV, Lateline, 1 September 2011.<br />

18 Each of the judgments in this<br />

case was based on strict statutory<br />

interpretation. Any suggested<br />

‘inconsistency’ between the Chief<br />

Justice’s judgment in this case and any<br />

other ignores the fact that the question<br />

on which this case turned had never<br />

before been decided in the court.<br />

19 Bradbury spoke on Sky News, as<br />

reported in ‘Offshore processing doubt’,<br />

Canberra Times, 1 September 2011.<br />

20 Tom Hyland, ‘Manne of the<br />

moment’, Age, 4 September 2011.<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 22 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Essays<br />

21 Plaintiff M70/2011 v Minister for<br />

Immigration and Citizenship; Plaintiff<br />

M106 of 2011 v Minister for Immigration<br />

and Citizenship [2011] HCA 32.<br />

22 David Marr, ‘Forget civil liberties,<br />

the defence of the 800 boat people<br />

rests on line-by-line analysis’, National<br />

Times, 23 August 2011.<br />

the case were from Afghanistan. They had arrived at Christmas Island from<br />

Indonesia on 4 August 2011 in a boat called SIEV 258. The asylum seekers<br />

claimed to have well-founded fears of persecution in Afghanistan ‘on<br />

grounds that would, if established, make them “refugees” to whom Australia<br />

owes protection obligations pursuant to the Refugee Convention’, to quote<br />

the court. 21<br />

The team behind the High Court challenge did not entirely escape media<br />

attention. The Melbourne Refugee and Immigration Legal Centre (RILC),<br />

of which Manne is executive director, was subjected to a takedown by the<br />

Australian in an article called ‘He’s the Manne of the moment’. In it, legal<br />

affairs reporter Chris Merritt called the RILC ‘GetUp! on steroids, complete with<br />

law degrees, and all paid for from out [sic] the public purse’. On the other hand,<br />

in the Age, in an article called (he must get this a lot) ‘Manne of the moment’,<br />

the same centre was described as operating ‘from upstairs offices at the scruffy<br />

end of Brunswick Street, Fitzroy’. Thus cast as both grassroots activist and<br />

fat cat lawyer, Manne came to represent the asylum seekers as their unofficial<br />

public advocate.<br />

Debbie Mortimer, meanwhile, was one of their leading advocates in the<br />

courtroom. When asylum seekers enter Australian territory, they invoke<br />

Australia’s protection obligations under international law. They are also<br />

governed by federal law. That law is, from time to time, tested in the courts.<br />

Mortimer’s job is to do the testing. According to commentator David Marr, the<br />

nub of the case was this:<br />

[The asylum-seekers’] defence is being built by close focus on the<br />

legislation, line by line, sub-clause by sub-clause. That’s how<br />

this court likes it. Only occasionally does Mortimer mention the<br />

‘fundamental liberties’ of her clients. Without the protection of the<br />

High Court, she said, ‘what happens to them will happen to them<br />

very quickly and in remote places.’ 22<br />

That focus on the legislation led the court to conclude that the asylum<br />

seekers could not be removed to Malaysia without their claims for refugee<br />

status first being assessed in Australia. Despite assurances from Australian<br />

and Malaysian authorities that the human rights of the asylum seekers would<br />

be protected under the deal, the problem was that there was not yet any legal<br />

protection in place. Unlike Australia, Malaysia was not party to the UN Refugee<br />

Convention of 1951. ‘This is a pointed message by the judiciary,’ said barrister<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 23 6/11/12 9:20 AM<br />

23

Debbie Mortimer and the Forensic Fight Lorin Clarke<br />

Greg Barns in The Drum, ‘that in a democratic society the rule of law must apply<br />

to anyone irrespective of their status as citizen or non-citizen.’ 23 Australia’s<br />

obligations under international law reached further than the government<br />

had thought.<br />

The rule of law advocate<br />

The Malaysia case was by no means the first time an Australian government<br />

had come across Debbie Mortimer. She worked on the case that determined<br />

that the decision-making processes in relation to asylum seekers on Christmas<br />

Island were reviewable by the courts and subject to the laws of natural justice. 24<br />

She worked on countless immigration cases during the Howard era and many<br />

since then. She successfully argued for the reversal of an order to expel two<br />

Kenyan boys from the country. The boys at the centre of the case, Mohammed<br />

and Hassan, neither of them yet eighteen, had stowed away on a boat that had<br />

landed in Australia in 1998. They applied for protection visas once on land and<br />

were rejected by the Refugee Review Tribunal—a decision they were entitled<br />

to appeal. What happened next became the central issue in the legal cases that<br />

followed. Mortimer and her fellow lawyers argued that there was a time period<br />

during which the boys could legally challenge the decision against them, and<br />

that during that period, the government had illegally expelled them from<br />

the country.<br />

The cases make fascinating reading. Mortimer’s clients were put on a<br />

Singapore Airlines flight that suddenly became the subject of a legal battle.<br />

The aeroplane was on the tarmac in Melbourne when Carolyn Graydon, then<br />

a lawyer at RILC, sought Mortimer’s assistance to go to court for an order to<br />

prevent the boys being removed. An order was made by Justice Tony North,<br />

but the plane took off. The question in court then became whether the flight<br />

would be turned around midair, grounded on Australian soil, or whether (as<br />

turned out to be the case) the government would agree to allow the plane to<br />

land in Singapore and the boys to be put straight back on a plane to Australia.<br />

It is unclear from court documents whether the government allowed the<br />

plane to leave the tarmac despite a court order not to do so. Mortimer’s team<br />

(led by barrister Ron Castan), started an action against the then minister<br />

Phillip Ruddock for contempt of court in relation to this conduct. The action<br />

was later settled.<br />

The drama surrounding the case did not end there. Having agreed to put<br />

the Kenyan boys back on a plane to Australia, the government made one<br />

more move that put the boys’ hopes of a temporary sanctuary in Australia<br />

24<br />

23 Greg Barns, ‘Victory for asylum<br />

seekers against legal fiction’, The<br />

Drum, 11 November 2010.<br />

24 Plaintiff M61 /2010E v<br />

Commonwealth of Australia [2010]<br />

HCA 41.<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 24 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Essays<br />

out of reach. Before leaving Singapore on their court-ordered trip home, they<br />

were issued with new visas. Those visas expired in the air on the trip back to<br />

Australia. As soon as the plane hit the ground in Melbourne, Mortimer’s clients<br />

were taken straight to detention. Their status as unaccompanied minors meant<br />

that their guardian, the state, was the very government attempting to deport<br />

them. They were in legal limbo. At this point, Mortimer withdrew from the<br />

case. Subsequent court documents describe how, after efforts to find suitable<br />

guardians for the boys failed, this happened: ‘the applicants lived with Ms<br />

Debra Mortimer, a barrister, who initially represented them’. Mohammed and<br />

Hassan are now Australian citizens.<br />

Despite her involvement in these cases, Mortimer is largely unknown to<br />

the public. She was never involved in student politics or social justice causes<br />

at university. Nor did she turn, as Julian Burnside did, from a Liberal voter<br />

into a human rights advocate. After doing her legal training in a small firm<br />

in Melbourne straight out of law school, Mortimer became an associate to Sir<br />

Gerard Brennan, then chief justice of the High Court. Brennan encouraged<br />

her to become a barrister straightaway, rather than taking the usual route<br />

of building up a client base in practice first. She did so. Now, she has a track<br />

record that includes some of the most high-profile cases in human rights law,<br />

discrimination law and environmental law. She is the head of the Human Rights<br />

Committee at the Victorian Bar. In December 2011 she was the joint recipient of<br />

the Tim McCoy Award for community legal work, the Law Institute of Victoria’s<br />

President’s Award, and the Australian Human Rights Commission Law Award.<br />

Mortimer was also the first woman to be awarded the Law Council of<br />

Australia’s President’s Medal for outstanding contribution to the Australian<br />

legal profession. She was joint winner of the 2012 Victorian Bar’s Public<br />

Interest Award for the Malaysia case. Some of the people she works alongside—<br />

Julian Burnside, David Manne, Robert Stary—are, if not household names,<br />

recognisable in the context of the debate. Mortimer appears in public too—on<br />

panels, in discussions, on radio. As her colleague Richard Niall SC points out,<br />

though, there are two forms of advocacy: advocacy in the courtroom, and<br />

advocacy for change in the community. ‘Debbie has always been more directed<br />

to the former rather than the latter,’ he says. Most of her work takes place<br />

in court.<br />

Nevertheless, one could be forgiven for casting Mortimer as a bolshie<br />

barrister motivated by a desire to oppose the recent right-wing trend in<br />

Australian immigration policy. The ‘Kenyan boys’ case seems, when read in<br />

its sociopolitical context, to be a direct challenge to the hubris of the Howard<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 25 6/11/12 9:20 AM<br />

25

Debbie Mortimer and the Forensic Fight Lorin Clarke<br />

government at the height of its power. The Malaysia case stopped the Gillard<br />

government in its tracks. Conversely, Mortimer’s lack of public profile could be<br />

indicative of a black-letter-law-obsessed book nerd insensitive to the political<br />

repercussions of her work. Her perspective is much more complex than either<br />

stereotype allows. It is, as Niall says, ‘no coincidence’ that she often acts for<br />

clients with no resources. On the other hand, he says, she has acted for ‘many<br />

other entities and organisations and individuals who are also entitled to<br />

representation’ but whose lives do not hang in the balance. She is, he says, first<br />

and foremost a lawyer.<br />

There is one key point Mortimer steadfastly refuses to concede. She insists<br />

she has no agenda. Her work is not politically or personally motivated. She<br />

works, in so far as she can, according to the cab rank principle—where lawyers<br />

take cases as they come rather than picking and choosing. In an interview with<br />

Waleed Aly on ABC radio, Aly attempted to draw Mortimer on whether the<br />

broader political implications of cases such as the Malaysia case were a factor in<br />

the way she undertook her day-to-day work. She didn’t budge. Despite the fact<br />

that her formidable reputation has been formed in part as a result of her work<br />

on human rights cases, she won’t even accept the term ‘human rights advocate’.<br />

Mortimer’s insistence on the executive meeting its own standards of procedural<br />

fairness is simply a position that understands the role of the court as interpreter<br />

of the laws made by the executive. She paused briefly after Aly’s question on<br />

this point and came up with ‘rule of law advocate’ instead.<br />

The idea of advocating for the protection of the rule of law is uncontroversial<br />

in the context of a representative democracy. The rule of law is the idea that<br />

governments should be subjected to the systems of checks and balances that<br />

are designed to protect us all from abuses of power. The section of legislation<br />

on which Mortimer relied in the Malaysia case had been hastily drawn up by<br />

the Howard government. Its swift conception happened in the wake of events<br />

surrounding the arrival in 2001 of the MV Tampa. The government’s response<br />

to this boat full of asylum seekers triggered a series of political dramas just<br />

before a federal election. So this was a government making a law that arguably<br />

did not anticipate the intricacies of the Malaysia case. To Mortimer, this is<br />

irrelevant. ‘All the High Court has done, in my view, is say that the words of the<br />

statute mean what they say.’ 25<br />

The result is that Australia is living up to its obligations under international<br />

and domestic law. What happens next isn’t up to her. ‘How Australia decides<br />

to [live up to its obligations] in the political sphere in terms of a regional<br />

solution, I see as a very different issue from what you do with people who are<br />

26<br />

25 Debbie Mortimer, interview with<br />

Waleed Aly, Radio National Summer<br />

Breakfast, 19 December 2011.<br />

Meanjin_71-4_FINAL.indd 26 6/11/12 9:20 AM

Essays<br />

26 Debbie Mortimer, interview with<br />

Waleed Aly.<br />

27 Mortimer, Wheeler Centre panel.<br />

in Australia and who are, like every other person who is in Australia, entitled to<br />

the protection of the rule of law.’ 26 This is where Mortimer is ‘quite conservative<br />

in some ways,’ she says. ‘You can make a difference if you insist on fairness and<br />

transparency and good decision-making.’ 27 In the wake of the Malaysia case, the<br />

government is again changing the legislation. Fair enough, says Mortimer, that<br />

means the system is working. The government can still be kept in check, either<br />

with another challenge in the courts or by the will of the people.<br />

The forensic fight<br />

Ask Debbie Mortimer what it is that drives her and she admits from the outset<br />

that a lot of it is competitive instinct. Her focus, she says, is on what she calls<br />

‘the forensic fight’ in the courtroom. It’s as though something comes over<br />

her there. She describes coming up against an apparently insurmountable<br />

obstacle in court as exciting; the challenge to her competitive spirit a red rag<br />

to a bull. The question of whether she can win the argument takes over and<br />

she has a reserve of self-confidence and cool-headedness she doesn’t usually<br />

access. ‘I can’t explain where that comes from,’ she says, genuinely baffled.<br />

In social settings Mortimer is self-possessed but understated, closer to shy than<br />

socially dominating. Watchful when listening, she delivers her own words in<br />

full, thoughtfully crafted, grammatically correct sentences that leave no room<br />

for doubt.<br />

Born into a blue-collar family in Auckland, she secured a job in a law library<br />

at the age of fourteen. Fascinated by the criminal cases she read, she decided<br />

there and then to be a lawyer. She is amused and surprised at her own ambition,<br />

which set her apart from the rest of her family, none of whom had ever had<br />

anything to do with the law. She doesn’t know what the people she grew up with<br />

made of her then, or what they might make of her now. That sense she has in<br />

court of not knowing where it comes from—the drive, the confidence and the<br />

gall to stand up to the forensic fight against the odds—seems to have kicked in<br />

at that moment as a fourteen-year-old.<br />

Mortimer does not see herself as a crusader. One of her areas of<br />

specialisation is administrative law, which governs the actions of people who<br />

work for and on behalf of government. Regardless of whether she is hired by<br />

government (which happens regularly, though never by the Department of<br />

Immigration) or by someone seeking to challenge a government, Mortimer<br />

tends to scrutinise government conduct for a living. She never gives the sense<br />

that she’s just doing her job though. Finding holes in contracts or prosecuting<br />