nomination by the Government of Australia - Sydney Opera House

nomination by the Government of Australia - Sydney Opera House

nomination by the Government of Australia - Sydney Opera House

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE<br />

NOMINATION BY THE GOVERNMENT OF AUSTRALIA<br />

FOR INSCRIPTION ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST 2006

© Commonwealth <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong> 2006<br />

This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under<br />

<strong>the</strong> Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced <strong>by</strong> any process<br />

without prior written permission from <strong>the</strong> Commonwealth, available<br />

from <strong>the</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>Government</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Environment<br />

and Heritage.<br />

Published <strong>by</strong>:<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>Government</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Environment and Heritage<br />

GPO Box 787<br />

Canberra ACT 2601<br />

National Library <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong> Cataloguing-in-Publication data:<br />

Commonwealth <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong><br />

<strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> <strong>nomination</strong> <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Government</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong><br />

for inscription on <strong>the</strong> World Heritage List<br />

Bibliography<br />

ISBN 0 642 55218 5<br />

I. Heritage<br />

II. Architecture<br />

III. Building and Construction<br />

Designed <strong>by</strong> Impress Design, <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

Printed <strong>by</strong> Allied Graphics

SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE<br />

NOMINATION BY THE GOVERNMENT OF AUSTRALIA<br />

OF THE SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE FOR INSCRIPTION<br />

ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST 2006<br />

PREPARED BY THE AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT AND THE NEW SOUTH WALES GOVERNMENT

CONTENTS<br />

PREFACE 4<br />

1. IDENTIFICATION OF THE PROPERTY 5<br />

1.A Country .....................................................7<br />

1.B State, province or region ...............................7<br />

1.C Name <strong>of</strong> property ........................................7<br />

1.D Geographical coordinates to <strong>the</strong> nearest second 7<br />

Property description .....................................7<br />

1.E Maps and plans ..........................................8<br />

1.F Area <strong>of</strong> nominated property and proposed<br />

buffer zone ................................................8<br />

2. DESCRIPTION 11<br />

2.A Description <strong>of</strong> property ................................ 13<br />

2.B History and development ............................. 20<br />

3. JUSTIFICATION FOR INSCRIPTION 25<br />

3.A Criteria under which inscription is proposed and<br />

justifi cation for inscription ............................. 27<br />

3.B Proposed statement <strong>of</strong> outstanding<br />

universal value .......................................... 44<br />

3.C Comparative analysis ................................. 46<br />

3.D Integrity and au<strong>the</strong>nticity .............................. 53<br />

4. STATE OF CONSERVATION AND FACTORS<br />

AFFECTING THE PROPERTY 57<br />

4.A Present state <strong>of</strong> conservation ....................... 59<br />

4.B Factors affecting <strong>the</strong> property ........................ 59<br />

(i) Development pressures .......................... 59<br />

(ii) Environmental pressures ......................... 60<br />

(iii) Natural disasters and risk preparedness ....... 61<br />

(iv) Visitor/tourism pressures .......................... 61<br />

(v) Number <strong>of</strong> inhabitants within <strong>the</strong> property<br />

and <strong>the</strong> buffer zone ................................. 62<br />

5. PROTECTION AND MANAGEMENT OF<br />

THE PROPERTY 63<br />

5.A Ownership ............................................... 65<br />

5.B Protective designation ................................ 65<br />

5.C Means <strong>of</strong> implementing protective measures .... 67<br />

5.D Existing plans related to municipality and region<br />

in which <strong>the</strong> proposed property is located ....... 68<br />

5.E Property management plan or o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

management system .................................. 70<br />

5.F Sources and levels <strong>of</strong> fi nance ....................... 72<br />

5.G Sources <strong>of</strong> expertise and training in conservation<br />

and management techniques ....................... 72<br />

5.H Visitor facilities and statistics ......................... 73<br />

5.I Policies and programs related to <strong>the</strong> presentation<br />

and promotion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> property ....................... 74<br />

5.J Staffi ng levels (pr<strong>of</strong>essional, technical,<br />

maintenance) ........................................... 74<br />

6. MONITORING 75<br />

6.A Key indicators for measuring state <strong>of</strong><br />

conservation ............................................. 77<br />

6.B Administrative arrangements for<br />

monitoring property .................................... 79<br />

6.C Results <strong>of</strong> previous reporting exercises ........... 80<br />

7. DOCUMENTATION 81<br />

7.A Photographs, slides, image inventory and<br />

authorisation table and o<strong>the</strong>r audiovisual<br />

materials ................................................. 83<br />

7.B Texts relating to protective designation, copies<br />

<strong>of</strong> property management plans or documented<br />

management systems and extracts <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

plans relevant to <strong>the</strong> property .................... 85<br />

7.C Form and date <strong>of</strong> most recent records or<br />

inventory <strong>of</strong> property ................................... 85<br />

7.D Address where inventory, records and archives<br />

are held .................................................. 86<br />

7.E Bibliography ............................................. 86<br />

8. CONTACT INFORMATION 93<br />

8.A Preparer .................................................. 95<br />

8.B Offi cial local institution/agency ...................... 95<br />

8.C O<strong>the</strong>r local institutions ................................. 96<br />

8.D Offi cial web address ................................... 96<br />

9. SIGNATURE ON BEHALF OF THE<br />

STATE PARTY 98<br />

10. APPENDICES 99<br />

10.A Biographies <strong>of</strong> Jørn Utzon and Ove Arup........ 101<br />

10.B List <strong>of</strong> illustrations ..................................... 107<br />

10.C Acknowledgments .................................... 110<br />

10.D Timeline <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong><br />

and its site ............................................. 112<br />

10.E Plans, sections and elevations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> .......................................... 113

4<br />

PREFACE<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> is pleased to present <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> for inscription on <strong>the</strong> World<br />

Heritage List. The <strong>nomination</strong> has been prepared jointly <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>Government</strong><br />

and <strong>the</strong> State <strong>Government</strong> <strong>of</strong> New South Wales. Many o<strong>the</strong>rs have assisted in <strong>the</strong><br />

preparation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>nomination</strong> and <strong>the</strong>ir assistance is gratefully acknowledged.<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> is an extraordinary building set in a stunning harbour. Since<br />

its inception it has captured <strong>the</strong> imagination <strong>of</strong> people <strong>the</strong> world over and has become<br />

a cultural symbol not only <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city in which it stands but <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n nation.<br />

This place is an outstanding human creation, an infl uential masterpiece <strong>of</strong> architecture<br />

that has unifi ed landscape and architecture in one monument.

1PART 1. IDENTIFICATION OF THE PROPERTY<br />

5

1.A COUNTRY<br />

Country – <strong>Australia</strong><br />

1.B STATE, PROVINCE OR REGION<br />

State – New South Wales<br />

1.C NAME OF PROPERTY<br />

<strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong><br />

1.D GEOGRAPHICAL COORDINATES TO THE NEAREST SECOND<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> is located on Bennelong Point at East Circular Quay in <strong>the</strong><br />

city <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong>, in <strong>the</strong> state <strong>of</strong> New South Wales, on <strong>the</strong> south-east coast <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>,<br />

at latitude 33° 51’ 35” S and longitude 151°12’ 50” E.<br />

Property description<br />

The description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> property is detailed below:<br />

•<br />

•<br />

Lot 5 in Deposited Plan 775888 at Bennelong Point, Parish <strong>of</strong> St. James, county<br />

<strong>of</strong> Cumberland, city <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong>; and<br />

Lot 4 in Deposited Plan 787933 at Circular Quay East, Parish <strong>of</strong> St. James, county<br />

<strong>of</strong> Cumberland, city <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong>.<br />

7

8<br />

Part 1. Identifi cation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> property<br />

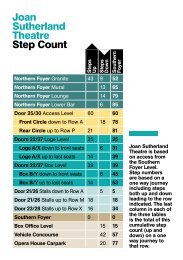

1.E MAPS AND PLANS<br />

Plans are provided at Figures 1.2, 1.3 and 1.4.<br />

WA<br />

Figure 1.2 Location map<br />

NT<br />

SA<br />

1.F AREA OF NOMINATED PROPERTY<br />

AND PROPOSED BUFFER ZONE<br />

Area <strong>of</strong> nominated property: 5.8 hectares<br />

Buffer zone: 438.1 hectares<br />

Total: 443.9 hectares<br />

The map below shows <strong>the</strong> location <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

within <strong>Australia</strong>.<br />

VIC<br />

QLD<br />

TAS<br />

NSW<br />

ACT<br />

SYDNEY<br />

N

The topographic map shows <strong>the</strong> location <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> and buffer zone within <strong>the</strong> city <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong>.<br />

The scale is 1:25 000. In <strong>the</strong> event that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> is inscribed on <strong>the</strong> World Heritage List,<br />

a buffer zone designed to protect its World Heritage<br />

values in relation to its setting on <strong>Sydney</strong> Harbour will<br />

come into effect.<br />

WAVERTON<br />

Berrys<br />

Bay<br />

GOAT<br />

ISLAND<br />

ULTIMO<br />

Darling Harbour<br />

McMAHONS POINT<br />

NORTH SYDNEY<br />

LAVENDER BAY<br />

DAWES POINT<br />

MILLERS POINT<br />

Lavender<br />

Bay<br />

THE<br />

ROCKS<br />

<strong>Sydney</strong><br />

Harbour<br />

Bridge<br />

SYDNEY<br />

MILSONS POINT<br />

<strong>Sydney</strong><br />

Cove<br />

Circular Quay<br />

Figure 1.3 Topographic map <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> site and buffer zone<br />

The buffer zone centres on <strong>the</strong> inner waters <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Sydney</strong> Harbour. It includes places around <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

Harbour within a radius <strong>of</strong> 2.5 kilometres that have<br />

been identifi ed as <strong>of</strong>fering critical views to and from<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> that contribute to its World<br />

Heritage signifi cance. See Part 5D for information on<br />

<strong>the</strong> proposed buffer zone.<br />

KIRRIBILLI<br />

Bennelong<br />

Point<br />

SYDNEY<br />

OPERA<br />

HOUSE<br />

Farm<br />

Cove<br />

Royal<br />

Botanical<br />

Gardens<br />

DARLINGHURST<br />

NEUTRAL BAY<br />

Neutral<br />

Bay<br />

Careening<br />

Cove<br />

WOOLLOOMOOLOO<br />

Wooloomooloo Bay<br />

Shell<br />

Cove<br />

POTTS<br />

POINT<br />

CREMORNE<br />

0 25 50m<br />

KEY<br />

<strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> site boundary<br />

Buffer zone<br />

CREMORNE POINT<br />

FORT<br />

DENISON<br />

Elizabeth<br />

Bay<br />

Mosman<br />

Bay<br />

ELIZABETH BAY<br />

RUSHCUTTERS BAY<br />

N<br />

9

10 Part 1. Identifi cation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> property<br />

The following site plan shows <strong>the</strong> property boundary<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> under <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong><br />

<strong>House</strong> Trust Act 1961 (NSW). The boundary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

World Heritage <strong>nomination</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong><br />

encompasses land on Bennelong Point owned <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Government</strong> <strong>of</strong> New South Wales and managed <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> Trust. The extent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> site is<br />

shown <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong> red boundary line.<br />

Additional plans, sections and elevations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> are provided at Appendix 10.E.<br />

0 25 50m<br />

Figure 1.4 Site plan<br />

N<br />

SYDNEY COVE<br />

Western Broadwalk<br />

Lower Forecourt<br />

Drama<br />

Theatre u<br />

Playhouse<br />

u<br />

Studio u<br />

SYDNEY HARBOUR<br />

Concert<br />

Hall<br />

Shells<br />

Restaurant<br />

Forecourt<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Broadwalk<br />

Podium Steps<br />

<strong>Opera</strong><br />

Theatre<br />

Shells<br />

Eastern Broadwalk<br />

Royal Botanic Gardens<br />

t Utzon Room<br />

<strong>Government</strong> <strong>House</strong><br />

FARM COVE<br />

Man ’O War<br />

Jetty

PART 2. DESCRIPTION<br />

11

The sun did not know how beautiful its light was, until<br />

it was refl ected <strong>of</strong>f this building (Louis Kahn quoted in<br />

Utzon 2002: 18).<br />

2.A DESCRIPTION OF PROPERTY<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> is a masterpiece <strong>of</strong> late modern architecture and an iconic<br />

building <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 20th century. It is admired internationally and treasured <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong> people <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Australia</strong>. Created <strong>by</strong> an architect who had been an avid sailor and understood <strong>the</strong> sea,<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> inhabits <strong>the</strong> world-famous maritime location on <strong>Sydney</strong> Harbour<br />

with such grace that it appears that <strong>the</strong> building belongs <strong>the</strong>re naturally. The massive<br />

concrete sculptural shells that form <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong>’s ro<strong>of</strong> appear like billowing<br />

sails fi lled <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong> sea winds with <strong>the</strong> sunlight and cloud shadows playing across <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

shining white surfaces. As its Danish architect Jørn Utzon envisaged, it is like a Gothic<br />

ca<strong>the</strong>dral that people will never tire <strong>of</strong> and ‘never be fi nished with’ (Utzon 1965a: 49).<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> represents a rare and outstanding architectural achievement:<br />

structural engineering that stretched <strong>the</strong> boundaries <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> possible and sculptural<br />

architectural forms that raise <strong>the</strong> human spirit. It not only represents <strong>the</strong> masterwork<br />

<strong>of</strong> Utzon but also <strong>the</strong> exceptional collaborative achievements <strong>of</strong> engineers, building<br />

contractors and o<strong>the</strong>r architects. The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> is unique as a great building<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world that functions as a world-class performing arts centre, a great urban<br />

sculpture and a public venue for community activities and tourism. This monumental<br />

building has become a symbol <strong>of</strong> its city and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n nation. The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong><br />

<strong>House</strong> ‘is not a simple entity… [but] alive with citizens and urbanity’ (Domicelj 2005).<br />

The outstanding natural beauty <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> setting <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> is intrinsic to<br />

its signifi cance. The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> is situated at <strong>the</strong> tip <strong>of</strong> a prominent peninsula<br />

projecting into <strong>Sydney</strong> Harbour (known as Bennelong Point) and within close proximity<br />

to <strong>the</strong> Royal Botanic Gardens and <strong>the</strong> world famous <strong>Sydney</strong> Harbour Bridge. Bennelong<br />

Point is fl anked <strong>by</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> Cove, Farm Cove and Macquarie Street (Figures 2.2 and 2.3).<br />

These sites saw <strong>the</strong> fi rst settlement, farming and governing endeavours <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> colony in<br />

<strong>the</strong> late 18th and early 19th centuries. Known as ‘Jubgalee’ <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong> traditional Aboriginal<br />

custodians (<strong>the</strong> Cadigal people), Bennelong Point was a meeting place <strong>of</strong> Aboriginal and<br />

European people during <strong>the</strong> early years <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> colony.<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> is an exceptional building composition. Its architectural form<br />

comprises three groups <strong>of</strong> interlocking vaulted ‘shells’, set upon a vast terraced platform<br />

(‘<strong>the</strong> podium’) and surrounded <strong>by</strong> terrace areas that function as pedestrian concourses<br />

(see Figure 1.4). The shells are faced in glazed <strong>of</strong>f-white tiles while <strong>the</strong> podium is clad in<br />

earth-toned, reconstituted granite panels. The two main halls are arranged side <strong>by</strong> side,<br />

oriented north-south with <strong>the</strong>ir axes slightly inclined. The auditoria are carved out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

high north end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> podium so that <strong>the</strong>y face south, towards <strong>the</strong> city, with <strong>the</strong> stage<br />

areas positioned between <strong>the</strong>m and <strong>the</strong> entrance foyers. The north and south ends <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> shells are hung with topaz glass walls that project diagonally outwards to form foyers,<br />

<strong>of</strong>fering views from inside and outside. The tallest shell reaches <strong>the</strong> height <strong>of</strong> a 20-storey<br />

building above <strong>the</strong> water. The shell structures cover nearly two hectares and <strong>the</strong> whole<br />

site is nearly six hectares (Figure 2.4).<br />

13

14<br />

Part 2. Description<br />

2.2<br />

The complex includes more than 1000 rooms, most <strong>of</strong><br />

which are located within <strong>the</strong> podium, as are virtually all<br />

<strong>the</strong> technical functions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> performing arts centre.<br />

The public spaces and promenades have a majestic<br />

quality, endowed <strong>by</strong> powerful structural forms and<br />

enhanced <strong>by</strong> vistas across <strong>the</strong> harbour and <strong>the</strong> Royal<br />

Botanic Gardens (Kerr 2003: 32). Strolling along <strong>the</strong><br />

open broadwalks surrounding <strong>the</strong> building, <strong>the</strong> public<br />

can experience <strong>the</strong> harbour setting <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong>, <strong>by</strong> day or night. The performing arts<br />

centre presents itself as an extraordinary sculpture in<br />

a magnifi cent city waterscape. Utzon envisaged that<br />

entering <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> would be a journey<br />

or transition, one that would intensify appreciation <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> man-made performance landscape. For those<br />

who climb <strong>the</strong> stairs rising from <strong>the</strong> forecourt to <strong>the</strong><br />

vast podium, <strong>the</strong> journey culminates on <strong>the</strong> top <strong>of</strong> a<br />

plateau where <strong>the</strong> audience meets <strong>the</strong> performers, in<br />

<strong>the</strong> ancient tradition <strong>of</strong> a procession culminating in a<br />

festival. Alternatively, those who enter via <strong>the</strong> covered<br />

lower concourse move upwards through <strong>the</strong> ‘austere,<br />

low-lit, linear spaces <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stairway and booking hall<br />

under concrete beams <strong>of</strong> unusual span and form’ in<br />

a transition that resembles ‘passing from a low nar<strong>the</strong>x<br />

or crypt to a grand Gothic ca<strong>the</strong>dral—light, airy and<br />

with a tall sculptural rib vault above’ (Utzon 2002: 9;<br />

Kerr 2003: 17).<br />

Figure 2.2 <strong>Sydney</strong> Harbour from 6,000 metres, 1972<br />

Figure 2.3 The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> projects into <strong>the</strong><br />

harbour with <strong>the</strong> central business district <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city behind.<br />

The Royal Botanic Gardens are directly to <strong>the</strong> south and<br />

Circular Quay, <strong>the</strong> hub <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong>’s domestic maritime<br />

transport system, is to <strong>the</strong> west.<br />

2.3 2.4<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> does not operate solely as<br />

a venue for opera, but as a multi-purpose venue that<br />

hosts a wide range <strong>of</strong> performing arts and community<br />

activities. These include classical and contemporary<br />

music, ballet, opera, drama and dance, events for<br />

children, outdoor activities and functions <strong>of</strong> all kinds.<br />

It is used as a venue <strong>by</strong> a wide range <strong>of</strong> organisations<br />

including performing arts companies, commercial<br />

promoters, schools, community groups, corporations,<br />

individuals and government agencies. Since its<br />

opening in 1973 over 45 million people have attended<br />

more than 100 000 performances at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong><br />

<strong>House</strong> and it is estimated that well over 100 million<br />

people have visited <strong>the</strong> site.<br />

Figure 2.4 The three groups <strong>of</strong> interlocking shells <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> are set on a vast terraced<br />

platform, 1979.

2.5<br />

Elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> and its site<br />

(1957–1973)<br />

… nowhere had anyone dared a monumentality<br />

on <strong>the</strong> scale <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> great platform and tiled<br />

vaults soaring fi fteen stories into <strong>the</strong> air<br />

(Weston 2002: 182).<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> was designed <strong>by</strong> Utzon<br />

and completed <strong>by</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n architects Hall Todd &<br />

Littlemore, with Peter Hall as <strong>the</strong> principal designer.<br />

The engineers were Ove Arup & Partners and <strong>the</strong><br />

building contractors were Civil & Civic for stage 1 and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Hornibrook Group for stages 2 and 3 (known as<br />

M.R. Hornibrook for stage 2). Utzon was re-engaged in<br />

1999 to design and oversee <strong>the</strong> future evolution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong>.<br />

The podium with its concourses, steps and forecourt<br />

The podium, with its origins in <strong>the</strong> ancient<br />

architectural idea <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> raised platform,<br />

becomes in <strong>Sydney</strong> a continuation and<br />

evocation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> local natural terrain, building<br />

as landscape, in a manner similar in intention<br />

to that <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r great Nordic architects, notably<br />

Asplund, Aalto and Pietilä (Carter 2005).<br />

Figure 2.5 Tsunami relief concert on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong><br />

<strong>House</strong> forecourt, 2005<br />

The base <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> rises up as a<br />

massive monolith <strong>of</strong> reinforced concrete, a grand<br />

granite-clad podium. Its monumental scale forms an<br />

artifi cial promontory that <strong>of</strong>fers continuity with <strong>the</strong><br />

harbour-side landscape. The podium measures 183<br />

metres <strong>by</strong> 95 metres rising to 25 metres above sea<br />

level and was <strong>the</strong> largest concrete form in <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

hemisphere in <strong>the</strong> 1960s (Murray 2004: 25). The<br />

podium lends a ceremonial aspect to <strong>the</strong> site and has<br />

been likened to a great stage or an altar <strong>of</strong> a majestic<br />

church. The inspiration for Utzon’s design came from<br />

Mayan monuments, Chinese temples and Islamic<br />

mosques. Just as <strong>the</strong> stone platform <strong>of</strong> Mayan temples<br />

allowed worshipers to escape <strong>the</strong> jungle, <strong>the</strong> podium<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> invites patrons and visitors<br />

to escape <strong>the</strong> city to a vantage point where <strong>the</strong>y can<br />

explore <strong>the</strong> magnifi cent vistas and experience <strong>the</strong><br />

building (Figure 2.6). Utzon’s visits to <strong>the</strong> Mayan ruins<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico inspired his design<br />

for <strong>the</strong> podium and <strong>the</strong> wide stairs leading up to it:<br />

The Mayan platform gave a new, cosmic<br />

dimension to <strong>the</strong> terrace <strong>by</strong> placing <strong>the</strong><br />

Indians in touch with <strong>the</strong> sky and an expanded<br />

universe above <strong>the</strong> jungle… It was Utzon’s<br />

conclusion that such stone jungle platforms<br />

were instruments for restoring <strong>the</strong> lost horizon<br />

(Drew 1999: 75–76).<br />

15

16<br />

Part 2. Description<br />

2.6 2.7 2.8<br />

The forecourt is a vast open space from which people<br />

ascend <strong>the</strong> stairs to <strong>the</strong> podium. Utzon’s vision was<br />

that <strong>the</strong> forecourt would be adaptable and function as a<br />

‘ga<strong>the</strong>ring place, a town square and outdoor auditorium’<br />

(Utzon 2002: 10). The forecourt is a focus for diverse<br />

and spectacular festivals and public events such as <strong>the</strong><br />

2000 Olympic Games and New Year’s Eve celebrations.<br />

Utzon’s design created spectacular and dramatic<br />

sculptural elevations. The podium steps, which lead<br />

up from <strong>the</strong> forecourt to <strong>the</strong> two main performance<br />

venues, are a great ceremonial stairway nearly 100<br />

metres wide and two storeys high. Visitors as well as<br />

patrons are welcome to ascend <strong>the</strong> stairway to view<br />

<strong>the</strong> spectacle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city, bridge and harbour. The<br />

podium steps rest on prestressed folded concrete<br />

beams spanning 49 metres that created one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

largest prestressed concrete spans in <strong>the</strong> world at<br />

<strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> construction in <strong>the</strong> 1960s. These beams<br />

form <strong>the</strong> low-lit and sculpturally beautiful ceiling to <strong>the</strong><br />

lower concourse which provides covered access to <strong>the</strong><br />

performance venues.<br />

Utzon’s design created an unconventional performing<br />

arts building in <strong>the</strong> way that it separated <strong>the</strong><br />

performance and technical functions. The two main<br />

performance venues were placed beneath <strong>the</strong> vaulted<br />

ro<strong>of</strong> shells, side <strong>by</strong> side upon <strong>the</strong> podium, while all<br />

<strong>the</strong> back-stage facilities and technical equipment for<br />

servicing <strong>the</strong>se were hidden within <strong>the</strong> podium.<br />

The idea has been to let <strong>the</strong> platform cut<br />

through like a knife, and separate primary and<br />

secondary functions completely. On top <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

platform <strong>the</strong> spectators receive <strong>the</strong> completed<br />

work <strong>of</strong> art and beneath <strong>the</strong> platform every<br />

preparation for it takes place (Utzon quoted in<br />

DEST & DUAP 1996: 62).<br />

Figure 2.6 The architectural idea <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> platform, utilised<br />

<strong>by</strong> Utzon at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong>, was inspired <strong>by</strong><br />

great architectural traditions including <strong>the</strong> temples <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Yucatan peninsula.<br />

This was a major departure from <strong>the</strong> traditional<br />

image and functioning <strong>of</strong> a performing arts centre<br />

and required <strong>the</strong> modifi cation <strong>of</strong> established internal<br />

circulation patterns, technical spaces, mechanical<br />

services and seating arrangements (Tombesi 2005, see<br />

upper fl oor plan, Appendix 10.D). Elevators were used<br />

to enable access from below and to transport stage<br />

sets from within <strong>the</strong> podium.<br />

The vaulted ro<strong>of</strong> shells (‘<strong>the</strong> shells’)<br />

The audience and <strong>the</strong> performance itself, all<br />

taking place on top <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plateau, should<br />

be covered with a ‘light’ sculptural ro<strong>of</strong>,<br />

emphasising <strong>the</strong> heavy mass <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plateau<br />

below (Utzon 2002: 9).<br />

The vaulted ro<strong>of</strong> shells with <strong>the</strong>ir glistening white<br />

tiled skin set amidst <strong>the</strong> grand waterscape setting<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> Harbour are an exceptional architectural<br />

element. Utzon originally conceived <strong>the</strong>m as ‘singlelayer,<br />

rib-reinforced parabolic shells’ but <strong>the</strong>y had to be<br />

refi ned during <strong>the</strong> design, engineering and construction<br />

process. The eventual design solution turned <strong>the</strong> shells<br />

into ‘arched vaults’ (Weston 2002: 130–132). The<br />

established usage continues to refer to <strong>the</strong>m as ‘shells’.<br />

Designed <strong>by</strong> Utzon in collaboration with Ove Arup<br />

& Partners, <strong>the</strong> fi nal shape <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shells was derived<br />

from <strong>the</strong> surface <strong>of</strong> a single imagined sphere, some 75<br />

metres in diameter. This geometry gives <strong>the</strong> building<br />

great coherence as well as allowing its construction<br />

to benefi t from <strong>the</strong> economies <strong>of</strong> prefabrication.<br />

Constructed ingeniously and laboriously <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Hornibrook Group, each shell is composed <strong>of</strong> precast<br />

rib segments radiating from a concrete pedestal<br />

and rising to a ridge beam. The ribs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shells are<br />

covered with chevron-shaped, precast concrete tile lids<br />

– <strong>the</strong> shallow dishes clad with ceramic tiles.<br />

Figure 2.7 The forecourt is a ‘ga<strong>the</strong>ring place, a town<br />

square and outdoor auditorium.’<br />

Figure 2.8 As <strong>the</strong> focal point <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong><br />

<strong>House</strong> is used as a centrepiece for public celebrations, 2004.

2.9<br />

The main areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shells are covered in white glossy<br />

tiles with matt tiles edging each segment. This creates<br />

a beautiful and ever-changing effect so that <strong>the</strong> building<br />

shines without creating a mirror effect. The tiles change<br />

colour according to <strong>the</strong> light and <strong>the</strong> perspective and<br />

can be anything from salmon pink, ochre, <strong>the</strong> palest <strong>of</strong><br />

violets and cream or ghostly white. The white glazed<br />

shells draw ‘attention to <strong>the</strong>ir identity as a freestanding<br />

sculpture’ (Drew 1999). The tiled surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shells is<br />

described in detail in Part 3.A.<br />

The two main shell structures cover <strong>the</strong> two main<br />

performance venues, known as <strong>the</strong> Concert Hall<br />

and <strong>Opera</strong> Theatre. The third set <strong>of</strong> shells that<br />

overlooks <strong>Sydney</strong> Cove was designed specially to<br />

house a restaurant.<br />

2.10 2.11<br />

Figure 2.9 The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> in its harbour setting,<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> Day 1988<br />

Figure 2.10 The shells <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong><br />

The glass walls<br />

Utzon wanted <strong>the</strong> walls to be expressed as<br />

a hanging curtain, a kind <strong>of</strong> glass waterfall<br />

that swings out as it descends to form a<br />

canopy over <strong>the</strong> lounge terraces and foyer<br />

entrances. Indeed, <strong>the</strong> north terraces are really<br />

great verandas with a glass canopy cover<br />

overlooking <strong>the</strong> harbour (Drew 1999).<br />

The glass walls <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> are a special<br />

feature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> building. They were constructed according<br />

to architect Peter Hall’s modifi ed design, which is<br />

described more fully in Part 3.A. The open end and sides<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shells are fi lled <strong>by</strong> hanging glass curtain walls. The<br />

topaz glazed infi ll between <strong>the</strong> shells and <strong>the</strong> podium<br />

was built as a continuous laminated glass surface with<br />

facetted folds tied to a structure <strong>of</strong> steel mullions. ‘A<br />

special feature is <strong>the</strong> canting out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lowest sheets,<br />

which allows views out without refl ections’ (Ken Woolley<br />

quoted in DEST & DUAP 1996: 70).<br />

Figure 2.11 Inside <strong>the</strong> smallest shell is a restaurant.<br />

17

18<br />

Part 2. Description<br />

The glass walls fl ood <strong>the</strong> building with sunlight and<br />

open it to <strong>the</strong> evening views <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city and harbour.<br />

Visitors <strong>of</strong>ten stand in <strong>the</strong> foyers under <strong>the</strong> shells<br />

mesmerised <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong> towering glass walls and intrigued<br />

at how <strong>the</strong> walls are held upright.<br />

Performance halls<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> has two main performance<br />

halls, <strong>the</strong> Concert Hall and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> Theatre. Utzon<br />

likened <strong>the</strong> relationship between <strong>the</strong> performance<br />

spaces and <strong>the</strong> shells to <strong>the</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> a walnut:<br />

‘<strong>the</strong> walnut’s hard shell’ protects <strong>the</strong> kernel’s ‘slightly<br />

wobbled form’ (Murphy 2004: 10–12). His original<br />

design conceived <strong>the</strong> halls as being largely constructed<br />

<strong>of</strong> plywood and hanging independently within <strong>the</strong><br />

vaulted shells so that <strong>the</strong>ir forms could be adapted to<br />

create <strong>the</strong> best acoustical performance. During <strong>the</strong><br />

fi nal design and construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> halls after Utzon’s<br />

departure in 1966, plywood was used in only one <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> halls.<br />

The Concert Hall is <strong>the</strong> largest performance space <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> and accommodates up to<br />

2700 people. Fitted high on <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn wall behind<br />

<strong>the</strong> stage is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> largest mechanical-action pipe<br />

organs in <strong>the</strong> world (Murray 2004: 135). Birch plywood,<br />

formed into radiating ribs on <strong>the</strong> suspended hollow<br />

raft ceiling, extends down <strong>the</strong> walls to meet laminated<br />

brush-box linings that match <strong>the</strong> fl oor.<br />

The <strong>Opera</strong> Theatre is <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> base for <strong>Opera</strong><br />

<strong>Australia</strong> and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n Ballet, and a regular venue<br />

for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> Dance Company. Its walls and ceiling<br />

are painted black and <strong>the</strong> fl oor is brush-box timber.<br />

2.12 2.13 2.14<br />

Figure 2.12 The glass walls to <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn foyers<br />

Figure 2.13 Model <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> in Utzon’s<br />

studio, 1966<br />

The Drama Theatre, <strong>the</strong> Playhouse and <strong>the</strong> Studio were<br />

developed as new performance spaces after Utzon’s<br />

departure. They are located in <strong>the</strong> podium.<br />

Public and back <strong>of</strong> house interiors<br />

Peter Hall’s design for <strong>the</strong> interiors used different<br />

fi nishes to distinguish <strong>the</strong> various spaces in <strong>the</strong><br />

building. Utzon regarded <strong>the</strong> foyers as ‘outside’ spaces,<br />

designed to be seen clearly through <strong>the</strong> glass walls.<br />

In keeping with Utzon’s vision <strong>the</strong> foyer fabric was<br />

designed with <strong>the</strong> same natural palette <strong>of</strong> textures and<br />

colours as <strong>the</strong> exterior. Off-form concrete painted white<br />

was used for <strong>the</strong> internal podium walls. O<strong>the</strong>r spaces<br />

that were to be used heavily <strong>by</strong> patrons, visitors, artists<br />

and staff were fi nished in <strong>the</strong> same white birch veneer<br />

as <strong>the</strong> Concert Hall.<br />

The veneer, which was applied to ply panels moulded<br />

to a shallow ‘U’ shape, was used in various forms to<br />

conceal services, absorb sound and accommodate<br />

<strong>the</strong> changing geometry in <strong>the</strong> building. Affectionately<br />

known as ‘wobblies’, <strong>the</strong> panels were used throughout<br />

<strong>the</strong> complex, most notably in <strong>the</strong> Drama Theatre and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Playhouse and <strong>the</strong>ir foyers, <strong>the</strong> major corridor<br />

systems and toilet facilities. The white birch veneer in<br />

its various forms brought visual unity to <strong>the</strong> performers’<br />

and staff spaces within <strong>the</strong> podium (Kerr 2003: 70).<br />

Figure 2.14 The interior <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Concert Hall

2.15 2.16<br />

Utzon Room<br />

The Utzon Room is a multi-purpose venue overlooking<br />

Farm Cove that is used for music recitals, productions<br />

for children, lecture programs and functions. Formerly<br />

<strong>the</strong> Reception Hall, <strong>the</strong> room was transformed in 2004<br />

under Utzon’s design guidance in association with<br />

his architect son, Jan Utzon, and <strong>Australia</strong>n architect<br />

Richard Johnson. It was <strong>the</strong> fi rst project in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong>’s upgrade program after Utzon was<br />

re-engaged to work on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong><br />

in 1999 (see Part 3.D for information on Utzon’s reengagement).<br />

The room was renamed in <strong>the</strong> architect’s<br />

honour and is presented as an au<strong>the</strong>ntic Utzon interior,<br />

both in its structure and interior design.<br />

The room is enlivened <strong>by</strong> a specially commissioned<br />

tapestry designed <strong>by</strong> Jørn Utzon and woven in<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong> Victorian Tapestry Workshop under<br />

<strong>the</strong> supervision <strong>of</strong> his daughter Lin Utzon, a renowned<br />

textile artist.<br />

To improve <strong>the</strong> room’s acoustics Utzon<br />

has designed a tapestry inspired <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Hamburg Symphonies <strong>of</strong> Carl Philipp Emanuel<br />

Bach. The originality <strong>of</strong> Bach’s symphonies<br />

has infl uenced generations <strong>of</strong> composers,<br />

and Utzon’s design transforms <strong>the</strong> music’s<br />

unexpected contrasts and silences into an<br />

optical experience … Measuring 14 metres in<br />

length, <strong>the</strong> tapestry is visible externally through<br />

<strong>the</strong> long window <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> podium’s side, so<br />

inscribing <strong>the</strong> façade symbolically with <strong>the</strong><br />

representation <strong>of</strong> music and connecting it with<br />

<strong>the</strong> life <strong>of</strong> its interiors (Murphy 2004: 13).<br />

Figure 2.15 The approach to <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atres from <strong>the</strong><br />

lower concourse<br />

Figure 2.16 Jørn Utzon with Norman Gillespie, Chief<br />

Executive Offi cer <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> Trust, and<br />

Utzon’s design for <strong>the</strong> tapestry for <strong>the</strong> Utzon Room<br />

Western loggia<br />

The creation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> western loggia is <strong>the</strong> fi rst major<br />

structural work to <strong>the</strong> exterior <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> building since <strong>the</strong><br />

opening <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong>. It was designed<br />

<strong>by</strong> Utzon following his re-engagement with <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> in 1999. The western loggia comprises<br />

a colonnade (45 metres long and fi ve metres wide)<br />

opening into <strong>the</strong> western side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> podium facing<br />

towards <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> Harbour Bridge. Nine openings<br />

have been created to open up <strong>the</strong> foyers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Drama<br />

Theatre, <strong>the</strong> Studio and <strong>the</strong> Playhouse to natural light<br />

and to allow access to harbour and city views (Hale &<br />

Macdonald 2005: 18–19). New bar and food facilities<br />

facing <strong>Sydney</strong> Harbour Bridge will create an impressive<br />

outdoor place for visitors to enjoy <strong>the</strong> building in its<br />

harbour setting.<br />

Utzon’s design for <strong>the</strong> western loggia was inspired<br />

<strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong> colonnades found in Mayan temples, which<br />

were one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> original design sources for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong>. The western loggia also reinforces<br />

Utzon’s initial design <strong>by</strong> connecting <strong>the</strong> foyers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

lower performance venues to <strong>the</strong> harbour setting, as<br />

is <strong>the</strong> case with <strong>the</strong> upper performance venues (<strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> Theatre and <strong>the</strong> Concert Hall).<br />

2.18<br />

2.17<br />

Figure 2.17 The recently refurbished Utzon Room, 2004<br />

Figure 2.18 The new loggia to <strong>the</strong> western elevation<br />

19

20<br />

Part 2. Description<br />

2.19<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>r detail concerning <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong><br />

A comprehensive description and evaluation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> complex and its elements,<br />

including <strong>the</strong>ir level <strong>of</strong> heritage signifi cance, are outlined<br />

in James Semple Kerr’s <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong>: a plan<br />

for <strong>the</strong> conservation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> and<br />

its site (referred to as ‘<strong>the</strong> Conservation Plan (SOH)’ in<br />

this <strong>nomination</strong>). A virtual tour <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong><br />

<strong>House</strong> is available on its web site at .<br />

Additional information on <strong>the</strong> elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> that represent some variations to Utzon’s<br />

original design concept (such as <strong>the</strong> glass walls and<br />

<strong>the</strong> interiors) is given in <strong>the</strong> Conservation Plan (SOH)<br />

and in Part 3.D. The Conservation Plan (SOH) and <strong>the</strong><br />

virtual tour (CD format) are provided as accompanying<br />

documentation to this <strong>nomination</strong>.<br />

2.20 2.21<br />

Figure 2.19 Utzon’s original competition drawing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> east<br />

elevation, 1956<br />

Figure 2.20 Utzon’s original competition drawing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

north elevation, 1956<br />

2.B HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT<br />

The history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> is as<br />

extraordinary and complex as <strong>the</strong> building. It is a<br />

story <strong>of</strong> vision, courage, belief, dedication, challenge,<br />

controversy and triumph. Its many remarkable<br />

elements include <strong>the</strong> submission <strong>of</strong> a visionary design<br />

that <strong>the</strong> judges courageously selected as winner; <strong>the</strong><br />

collaborative partnership <strong>of</strong> architect and engineer that<br />

triumphed over enormous odds to produce a solution<br />

to <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shells that was as groundbreaking<br />

as <strong>the</strong> design was ingenious; <strong>the</strong> breach<br />

created <strong>by</strong> Utzon’s departure from <strong>the</strong> project in 1966<br />

in <strong>the</strong> face <strong>of</strong> controversial cost and time overruns;<br />

and Utzon’s re-engagement with his project three<br />

decades later to oversee future changes to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong>.<br />

Figure 2.21 Utzon’s competition drawing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> podium<br />

looking towards <strong>the</strong> major and minor halls, 1956

2.22<br />

Figure 2.22 The front page <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> Morning Herald,<br />

30 January 1957<br />

21

22<br />

Part 2. Description<br />

2.23<br />

International design competition 1956<br />

A major cultural centre for <strong>Sydney</strong> and its siting at<br />

Bennelong Point had been discussed since <strong>the</strong> 1940s.<br />

Eugene Goossens, <strong>the</strong> British-born conductor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Sydney</strong> Symphony Orchestra, fi rst proposed this site<br />

in 1948, a recommendation that was later accepted <strong>by</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> New South Wales Premier, John Joseph Cahill. In<br />

1956 <strong>the</strong> New South Wales <strong>Government</strong> called an openended<br />

international design competition and appointed<br />

an independent jury, ra<strong>the</strong>r than commissioning a<br />

local fi rm. The competition brief provided broad<br />

specifi cations to attract <strong>the</strong> best design talent in <strong>the</strong><br />

world. Open to all architects from around <strong>the</strong> globe, it<br />

did not specify design parameters or set a cost limit.<br />

The main requirement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> competition brief was a<br />

design for a dual function building with two performance<br />

halls. The competition generated enormous interest<br />

in <strong>Australia</strong> and overseas: 933 architects registered <strong>of</strong><br />

whom 233 (mostly from overseas) submitted a design<br />

on a strictly anonymous basis (Messent 1997: 60–99).<br />

2.24<br />

The New South Wales <strong>Government</strong>’s decision<br />

to commission Utzon as <strong>the</strong> sole architect was<br />

unexpected, bold and visionary. There was scepticism<br />

as to whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> structure could be built given Utzon’s<br />

limited experience, <strong>the</strong> rudimentary and unique design<br />

concept and <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> any engineering advice.<br />

The competition drawings were largely diagrammatic,<br />

<strong>the</strong> design had not been fully costed and nei<strong>the</strong>r Utzon<br />

nor <strong>the</strong> jury had consulted a structural engineer (Murray<br />

2004: 13).<br />

Utzon’s design concept included unprecedented<br />

architectural forms and demanded solutions that<br />

required new technologies and materials. Utzon was<br />

only 38 years old and while he was starting to gain<br />

a reputation as an innovative designer he had just a<br />

handful <strong>of</strong> small-scale works to his credit. This was<br />

quite young for an architect to tackle such a large and<br />

complex building, particularly given <strong>the</strong> failure <strong>of</strong> several<br />

talented but inexperienced winners <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r international<br />

competitions (Weston 2002: 119). The New South<br />

Wales <strong>Government</strong> also faced public pressure to select<br />

an <strong>Australia</strong>n architect.<br />

Figure 2.23 One <strong>of</strong> Utzon’s original competition drawings, 1956<br />

Figure 2.24 The competition judges with <strong>the</strong> design, from left to<br />

right: renowned English architect Leslie Martin; Cobden Parkes (NSW<br />

<strong>Government</strong> Architect); eminent American-based Finnish architect<br />

Eero Saarinen, and H Ingham Ashworth, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Architecture,<br />

University <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong>.

2.25<br />

Yet <strong>the</strong>re was a spirit <strong>of</strong> adventure and willingness to<br />

explore new ideas in <strong>the</strong> postwar years in <strong>Australia</strong>.<br />

There was an impetus in some circles to transform<br />

<strong>Sydney</strong> into a new cultural metropolis and this<br />

escalated following <strong>the</strong> decision to hold <strong>the</strong> 1956<br />

Olympic Games in Melbourne (Murray 2004: 2). Ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

key driving force behind <strong>the</strong> genesis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> was Premier Cahill’s strong commitment<br />

to create <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> as a ‘People’s<br />

Palace’ (Weston 2002: 114).<br />

Construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong><br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> is <strong>of</strong>ten thought <strong>of</strong> as<br />

being constructed in three stages and this is useful in<br />

understanding <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> three key elements<br />

<strong>of</strong> its architectural composition: <strong>the</strong> podium (stage 1:<br />

1958–1961), <strong>the</strong> vaulted shells (stage 2: 1962–1967)<br />

and <strong>the</strong> glass walls and interiors (stage 3: 1967–1973).<br />

Architect Jørn Utzon conceived <strong>the</strong> overall design<br />

and supervised <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> podium and<br />

<strong>the</strong> vaulted shells. The glass walls and interiors were<br />

designed and <strong>the</strong>ir construction supervised <strong>by</strong> architect<br />

Peter Hall supported <strong>by</strong> Lionel Todd and David<br />

Littlemore in conjunction with <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>n New South<br />

Wales <strong>Government</strong> Architect, Ted Farmer. Peter Hall<br />

was in conversation with Utzon on various aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> design for at least 18 months following his<br />

departure (Hall 1967). Ove Arup & Partners provided<br />

<strong>the</strong> engineering expertise for all three stages <strong>of</strong><br />

construction, working with building contractors<br />

Civil & Civic on stage 1 and <strong>the</strong> Hornibrook Group on<br />

stages 2 and 3.<br />

Design and construction were closely intertwined and<br />

this was a distinctive feature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong><br />

<strong>House</strong>. Utzon’s unique design toge<strong>the</strong>r with his<br />

radical approach to <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> building<br />

fostered an exceptional collaborative and innovative<br />

environment. His collaborative model marked a break<br />

from conventional architectural practice at <strong>the</strong> time.<br />

The separation <strong>of</strong> architecture and engineering that had<br />

begun in <strong>the</strong> 19th century was not responsive to <strong>the</strong><br />

complex nature <strong>of</strong> modern architecture. The striving for<br />

new architectural forms using new materials demanded<br />

new methodologies and architects in some countries<br />

had started seeking more creative input from engineers.<br />

Utzon took this one step fur<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> distinctive<br />

approach he employed for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong>.<br />

This is described in more detail in Part 3.A.<br />

The scale <strong>of</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong><br />

was enormous. Over 30 000 cubic metres <strong>of</strong> rock<br />

and soil had to be removed from <strong>the</strong> site and <strong>the</strong><br />

construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shell structure required <strong>the</strong> world’s<br />

largest crane. The design solution and construction <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> shell structure took eight years to complete and <strong>the</strong><br />

development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> special ceramic tiles for <strong>the</strong> shells<br />

took over three years.<br />

Figure 2.25 Peter Hall, Lionel Todd and David Littlemore Figure 2.26 Ove Arup’s team from left to right: Mick Lewis,<br />

Ove Arup and Jack Zunz on site<br />

2.26<br />

23

24<br />

Part 2. Description<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> literally became a testing<br />

laboratory and a vast, open-air precasting factory.<br />

Examples <strong>of</strong> engineering and technological feats and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r innovations are described in Part 3.A.<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> took 16 years to build at an<br />

estimated cost <strong>of</strong> A$102 million. This was six years<br />

longer than scheduled and 10 times more than its<br />

original estimated cost (Murray 2004: xv). Weston<br />

points out that it was miraculous that Utzon was given<br />

so much freedom to explore, experiment and succeed<br />

in building <strong>the</strong> structure at all (Weston 2002: 184).<br />

Certainly it was expensive and diffi cult to build,<br />

but so were Gothic ca<strong>the</strong>drals and many<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r major buildings, and part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir appeal<br />

is <strong>the</strong> feeling <strong>of</strong> embodied energy and effort<br />

expended in achieving a great work … [But] as<br />

<strong>the</strong> fi rst and still unrivalled modern ‘blockbuster<br />

building’, it must have paid for itself many<br />

times over <strong>by</strong> giving <strong>Sydney</strong> and <strong>Australia</strong> an<br />

unrivalled and instantly recognisable emblem—<br />

‘<strong>the</strong> greatest public-relations building since <strong>the</strong><br />

pyramids’ to quote an <strong>Australia</strong>n MP (Weston<br />

2002: 184).<br />

Probably <strong>the</strong> most signifi cant feature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

whole <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> story is <strong>the</strong><br />

astonishing reality that in a modern society with<br />

all its checks and balances, its accountants<br />

and accountability, its budgets and budgetary<br />

controls, a folly <strong>of</strong> this scale could be<br />

contemplated. In o<strong>the</strong>r words it is nothing<br />

short <strong>of</strong> miraculous that it happened at all<br />

(Zunz 1973: 2).<br />

2.27 2.28<br />

Figure 2.27 Paul Robeson sings to <strong>the</strong> construction workers<br />

in 1960<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> as a performing<br />

arts centre<br />

Many famous artistic performers from <strong>Australia</strong> and<br />

overseas have been associated with <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong>. The fi rst performance at <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> took place in 1960, long before it<br />

<strong>of</strong>fi cially opened, when <strong>the</strong> American actor and singer<br />

Paul Robeson climbed onto <strong>the</strong> scaffolding at <strong>the</strong><br />

construction site to sing to <strong>the</strong> workers. Thirteen<br />

years later <strong>the</strong> fi rst <strong>of</strong>fi cial performance was given<br />

in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> Theatre on 28 September 1973 <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>Opera</strong> Company. On 20 October 1973 <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> was <strong>of</strong>fi cially opened <strong>by</strong> Queen<br />

Elizabeth II. During <strong>the</strong> period immediately after <strong>the</strong><br />

opening some 300 journalists arrived from all over <strong>the</strong><br />

world ‘to see if <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> was to be a<br />

white elephant or a sacred cow’ (Kerr 1993: 25). A Los<br />

Angeles correspondent wrote:<br />

This, without question, must be <strong>the</strong> most<br />

innovative, <strong>the</strong> most daring, <strong>the</strong> most dramatic<br />

and in many ways, <strong>the</strong> most beautifully<br />

constructed home for <strong>the</strong> lyric and related<br />

muses in modern times (Kerr 1993: 25).<br />

A timeline <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> is at<br />

Appendix 10.D.<br />

Figure 2.28 Aerial view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> during<br />

its opening on 20 October 1973

25<br />

3PART 3. JUSTIFICATION FOR INSCRIPTION

… we’re here to nudge forward <strong>the</strong> frontiers <strong>of</strong><br />

science (Utzon quoted in Murray 2004: 152).<br />

3.A CRITERIA UNDER WHICH INSCRIPTION IS PROPOSED<br />

AND JUSTIFICATION FOR INSCRIPTION<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> fulfi ls <strong>the</strong> defi nition <strong>of</strong> ‘monument’ according to Article 1 <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> World Heritage Convention (UNESCO 1972) as an architectural work <strong>of</strong> outstanding<br />

universal value from <strong>the</strong> point <strong>of</strong> view <strong>of</strong> both art and science. The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong><br />

<strong>House</strong> meets criterion (i) set out in paragraph 77 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>tional guidelines for <strong>the</strong><br />

implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World Heritage Convention.<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> is a work <strong>of</strong> human creative genius, and a masterful<br />

architectural and engineering achievement. It represents an outstanding conjunction not<br />

only <strong>of</strong> architecture and engineering but also <strong>of</strong> sculpture, landscape design and urban<br />

design. It is an ensemble that has reconfi gured <strong>the</strong> way public architecture can defi ne<br />

a city’s identity in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> an iconic signature building (Goad 2005). It was a turning<br />

point in <strong>the</strong> late Modern Movement, a daring and visionary experiment resulting in an<br />

unparalleled building that defi ed categorisation and found an original style in which to<br />

express civic values in monumental public buildings. The infl uences that resulted in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong>’s unique form include organic natural forms and an eclectic range<br />

<strong>of</strong> aes<strong>the</strong>tic cultural infl uences, brilliantly unifi ed in <strong>the</strong> one sculptural building. This was<br />

made possible through engineering innovation on a grand scale. Moreover, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong>’s signifi cance is intrinsically tied to its harbour-side site. Utzon’s design, an<br />

extraordinarily appropriate response to its site, created an enormously successful urban<br />

focus for <strong>the</strong> city <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> and captured <strong>the</strong> imagination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world. The pioneering<br />

collaborative design approach also set a precedent for best practice in building and <strong>the</strong><br />

engineering research to solve <strong>the</strong> unprecedented challenges was virtually unknown in <strong>the</strong><br />

building industry.<br />

The outstanding universal values <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> are demonstrated in <strong>the</strong><br />

building’s recognition as:<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

3.A (i) a masterpiece <strong>of</strong> late modern architecture;<br />

- multiple strands <strong>of</strong> creativity,<br />

- a great urban sculpture,<br />

- masterful syn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>of</strong> architectural ideas,<br />

3.A (ii) oustanding achievements in structural engineering and technological innovation;<br />

3.A (iii) a world-famous iconic building <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 20th century.<br />

These values are <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> collective genius <strong>of</strong> Utzon and <strong>the</strong> team responsible<br />

for <strong>the</strong> building’s construction.<br />

27

28<br />

Part 3. Justifi cation for inscription<br />

3.2<br />

3.A (i) A masterpiece <strong>of</strong> late modern architecture<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> is a great architectural work<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 20th century. Its values are best demonstrated<br />

through <strong>the</strong> specifi c characteristics <strong>of</strong> its architecture<br />

and will be discussed under <strong>the</strong> following headings:<br />

multiple strands <strong>of</strong> creativity, a great urban sculpture<br />

and a world famous iconic building.<br />

Multiple strands <strong>of</strong> creativity: Utzon and<br />

collective ingenuity<br />

The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> was <strong>the</strong> result primarily <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

creative genius <strong>of</strong> Jørn Utzon, as well as <strong>the</strong> ingenuity<br />

<strong>of</strong> a collaborative team <strong>of</strong> architects, engineers,<br />

building contractors and manufacturers. The <strong>Sydney</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> was acclaimed as ‘a masterpiece—Jørn<br />

Utzon’s masterpiece’ <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong> Pritzker Prize jury in 2003<br />

(Pritzker Prize web page 2005). It is also renowned as<br />

Utzon’s masterwork. Utzon’s unique design concept<br />

and his distinctive approach to <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

building fostered an exceptional collective creativity and<br />

demanded exceptional engineering and technological<br />

feats. Outstanding design and construction solutions<br />

were achieved <strong>by</strong> London-based engineers Ove Arup<br />

& Partners, <strong>Australia</strong>n architects Hall Todd & Littlemore<br />

and many o<strong>the</strong>rs in <strong>the</strong> construction industry.<br />

Figure 3.2 The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> at dusk<br />

Utzon, Ove Arup and engineer Peter Rice were<br />

awarded <strong>the</strong> Royal Institute <strong>of</strong> British Architects’<br />

Gold Medal for Architecture (1978, 1966 and 1992<br />

respectively), which includes among its recipients o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

internationally distinguished architects and engineers<br />

such as Le Corbusier, Pier Luigi Nervi, Oscar Niemeyer<br />

and Frank Gehry. See Appendix 10.A for biographies<br />

<strong>of</strong> Jørn Utzon and Ove Arup.<br />

Utzon’s design represented an exceptional response<br />

to <strong>the</strong> challenges set <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1956 international<br />

competition and clearly marked him out from <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

entrants. His composition was based on a simple<br />

opposition <strong>of</strong> three groups <strong>of</strong> interlocking shell vaults<br />

resting on a heavy terraced platform. The design was<br />

<strong>the</strong> only one that arranged <strong>the</strong> two performance halls<br />

side <strong>by</strong> side—<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r entrants placed <strong>the</strong>m end<br />

to end. This arrangement helped to give <strong>the</strong> building<br />

a sculptural appearance that could be experienced<br />

and appreciated from land, sea and air as one moved<br />

around <strong>the</strong> building. The beautiful shells juxtaposed<br />

against <strong>the</strong> massive podium were radically new and<br />

particularly impressed <strong>the</strong> jury. Utzon’s composition<br />

also created a unique design for a concert hall that<br />

has been described as ‘original to <strong>the</strong> point <strong>of</strong> being<br />

revolutionary … [it] had absolutely no association with<br />

<strong>the</strong> classical design <strong>of</strong> concert halls’ (Danish acoustics<br />

consultant Jordan quoted in Murray 2004: 67).

Utzon’s design modifi ed <strong>the</strong> established internal<br />

circulation patterns, seating layouts and positioning<br />

<strong>of</strong> technological and functional requirements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

conventional arts centre (Tombesi 2005). The design<br />

also provided a highly original response to <strong>the</strong> harbour<br />

setting, inspired <strong>by</strong> <strong>the</strong> site, people and nature toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

with an assortment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>mes refi ned from o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

architecture, particularly ancient forms and styles<br />

(Weston 2004a: 28, 34–35). The jury was impressed<br />

that <strong>the</strong> ‘white sail-like forms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shell vaults relate<br />

as naturally to <strong>the</strong> harbour as <strong>the</strong> sails <strong>of</strong> its yachts’<br />

(Murray 2004: 10). Ano<strong>the</strong>r important aspect was <strong>the</strong><br />

design <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> massive open platform and cave-like<br />

shells to entice visitors to inhabit and explore <strong>the</strong>m<br />

(Weston 2004a: 34–36). The <strong>Sydney</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>House</strong> was<br />

very much designed to be a people’s building. These<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r outstanding elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> design are<br />

described below.<br />

Utzon’s unique design was acclaimed as <strong>the</strong> work<br />

<strong>of</strong> a genius in <strong>Australia</strong> and internationally but it also<br />

attracted critics. The competition jury was convinced<br />

that Utzon’s design was ‘<strong>the</strong> most original and creative<br />

submission … capable <strong>of</strong> being one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> great<br />