Gender Check - ERSTE Stiftung

Gender Check - ERSTE Stiftung

Gender Check - ERSTE Stiftung

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

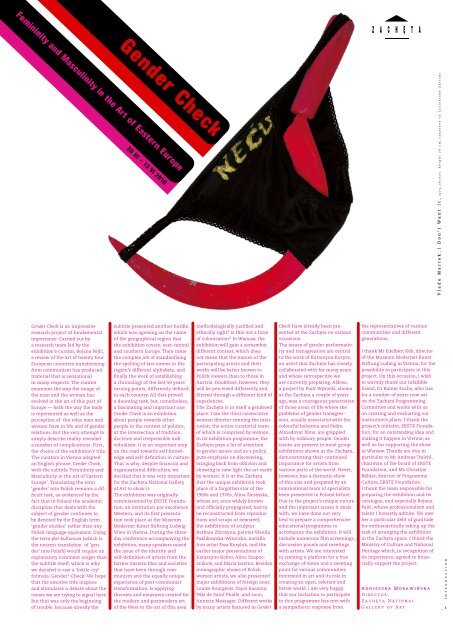

Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe<br />

<strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Check</strong> is an impressive<br />

research project of fundamental<br />

importance. Carried out by<br />

a research team led by the<br />

exhibition’s curator, Bojana Pejić,<br />

a review of the art of twenty four<br />

European countries transforming<br />

from communism has produced<br />

material that is sensational<br />

in many respects. The curator<br />

examines the way the image of<br />

the man and the woman has<br />

evolved in the art of this part of<br />

Europe — both the way the body<br />

is represented as well as the<br />

perception of the roles men and<br />

women have in life and of gender<br />

relations. But the very attempt to<br />

simply describe reality revealed<br />

a number of complications. First,<br />

the choice of the exhibition’s title.<br />

The curators in Vienna adopted<br />

an English phrase, <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Check</strong>,<br />

with the subtitle ‘Femininity and<br />

Masculinity in the Art of Eastern<br />

Europe’. Translating the term<br />

‘gender’ into Polish remains a difficult<br />

task, as evidenced by the<br />

fact that in Poland the academic<br />

discipline that deals with the<br />

subject of gender continues to<br />

be denoted by the English term<br />

‘gender studies’ rather than any<br />

Polish-language equivalent. Using<br />

the term płeć kulturowa (which is<br />

the nearest translation of ‘gender’<br />

into Polish) would require an<br />

explanatory comment longer than<br />

the subtitle itself, which is why<br />

we decided to use a ‘battle-cry’<br />

formula: <strong>Gender</strong>? <strong>Check</strong>! We hope<br />

that the emotive title inspires<br />

and stimulates a debate about the<br />

issues we are trying to signal here.<br />

But that was only the beginning<br />

of trouble, because already the<br />

<strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Check</strong><br />

20 III – 13 VI 2010<br />

subtitle presented another hurdle,<br />

which was agreeing on the name<br />

of the geographical region that<br />

the exhibition covers: east-central<br />

and southern Europe. Then came<br />

the complex job of standardising<br />

the spelling of last names in the<br />

region’s different alphabets, and<br />

finally the work of establishing<br />

a chronology of the last 50 years’<br />

turning points, differently defined<br />

in each country. All that proved<br />

a daunting task, but, nonetheless,<br />

a fascinating and important one.<br />

<strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Check</strong> is an exhibition<br />

about people towards other<br />

people in the context of politics,<br />

at the intersection of tradition,<br />

doctrine and irrepressible individualism.<br />

It is an important step<br />

on the road towards self-knowledge<br />

and self-definition in culture.<br />

That is why, despite financial and<br />

organisational difficulties, we<br />

decided that it was very important<br />

for the Zachęta National Gallery<br />

of Art to show it.<br />

The exhibition was originally<br />

commissioned by <strong>ERSTE</strong> Foundation,<br />

an institution par excellence<br />

Western, and its first presentation<br />

took place at the Museum<br />

Moderner Kunst <strong>Stiftung</strong> Ludwig<br />

Wien in Vienna. During the threeday<br />

conference accompanying the<br />

exhibition, many speakers raised<br />

the issue of the identity and<br />

self-definition of artists from the<br />

former Eastern bloc and societies<br />

that have been through communism<br />

and the equally unique<br />

experience of post-communist<br />

transformation. Is applying<br />

theories and measures created for<br />

the modern and postmodern art<br />

of the West to the art of this area<br />

methodologically justified and<br />

ethically right? Is this not a form<br />

of colonisation? In Warsaw, the<br />

exhibition will gain a somewhat<br />

different context, which does<br />

not mean that the names of the<br />

participating artists and their<br />

works will be better known to<br />

Polish viewers than to those in<br />

Austria. Doubtless, however, they<br />

will be perceived differently and<br />

filtered through a different kind of<br />

experiences.<br />

The Zachęta is in itself a gendered<br />

place: I am the third consecutive<br />

woman director running the institution,<br />

the entire curatorial team<br />

of which is comprised by women.<br />

In its exhibition programme, the<br />

Zachęta pays a lot of attention<br />

to gender issues and as a policy,<br />

puts emphasis on discovering,<br />

bringing back from oblivion and<br />

showing in new light the art made<br />

by women. It is at the Zachęta<br />

that the unique exhibition took<br />

place of a forgotten star of the<br />

1960s and 1970s, Alina Ślesińska,<br />

whose art, once widely known<br />

and officially propagated, had to<br />

be reconstructed from reproductions<br />

and scraps of newsreel;<br />

the exhibitions of sculptor<br />

Barbara Zbrożyna, painter Wanda<br />

Paklikowska-Winnicka, installation<br />

artist Ewa Kuryluk, and the<br />

earlier major presentations of<br />

Katarzyna Kobro, Alina Szapocznikow,<br />

and Maria Jarema. Besides<br />

monographic shows of Polish<br />

women artists, we also presented<br />

major exhibitions of foreign ones:<br />

Louise Bourgeois, Yayoi Kusama,<br />

Niki de Saint Phalle, and soon,<br />

Annette Messager. Different works<br />

by many artists featured in <strong>Gender</strong><br />

<strong>Check</strong> have already been presented<br />

at the Zachęta on various<br />

occasions.<br />

The issues of gender performativity<br />

and transgression are central<br />

to the work of Katarzyna Kozyra,<br />

an artist that Zachęta has closely<br />

collaborated with for many years<br />

and whose retrospective we<br />

are currently preparing. Aldona,<br />

a project by Piotr Wysocki, shown<br />

at the Zachęta a couple of years<br />

ago, was a courageous penetration<br />

of those areas of life where the<br />

problems of gender transgression,<br />

usually associated with the<br />

colourful bohemia and Pedro<br />

Almodovar films, are grappled<br />

with by ordinary people. <strong>Gender</strong><br />

issues are present in most group<br />

exhibitions shown at the Zachęta,<br />

demonstrating their continued<br />

importance for artists from<br />

various parts of the world. Never,<br />

however, has a thematic show<br />

of this size and prepared by an<br />

international team of specialists<br />

been presented in Poland before.<br />

Due to the project’s unique nature<br />

and the important issues it deals<br />

with, we have done our very<br />

best to prepare a comprehensive<br />

educational programme to<br />

accompany the exhibition. It will<br />

include numerous film screenings,<br />

discussion panels and meetings<br />

with artists. We are interested<br />

in creating a platform for a free<br />

exchange of views and a meeting<br />

point for various communities<br />

interested in art and its role in<br />

creating an open, tolerant and<br />

better world. I am very happy<br />

that our invitation to participate<br />

in this programme has met with<br />

a sympathetic response from<br />

the representatives of various<br />

communities and different<br />

generations.<br />

I thank Mr Edelbert Köb, director<br />

of the Museum Moderner Kunst<br />

<strong>Stiftung</strong> Ludwig in Vienna, for the<br />

possibility to participate in this<br />

project. On this occasion, I wish<br />

to warmly thank our infallible<br />

friend, Dr Rainer Fuchs, who has<br />

for a number of years now sat<br />

on the Zachęta Programming<br />

Committee and works with us<br />

on creating and evaluating our<br />

institution’s plans. I thank the<br />

project’s initiator, <strong>ERSTE</strong> Foundation,<br />

for an outstanding idea and<br />

making it happen in Vienna, as<br />

well as for supporting the show<br />

in Warsaw. Thanks are due in<br />

particular to Mr Andreas Treichl,<br />

chairman of the board of <strong>ERSTE</strong><br />

Foundation, and Ms Christine<br />

Böhler, director of Programme<br />

Culture, <strong>ERSTE</strong> Foundation.<br />

I thank the team responsible for<br />

preparing the exhibition and its<br />

catalogue, and especially Bojana<br />

Pejić, whose professionalism and<br />

talent I honestly admire. We owe<br />

her a particular debt of gratitude<br />

for enthusiastically taking up the<br />

task of arranging the exhibition<br />

in the Zachęta space. I thank the<br />

Ministry of Culture and National<br />

Heritage which, in recognition of<br />

its importance, agreed to financially<br />

support the project.<br />

Agnieszka Morawińska<br />

Director,<br />

Z a c h ę t a N a t i o n a l<br />

Gallery of Art<br />

V l a d o M a r t e k _ I D o n ’ t W a n t I t _ 1 9 7 9 _ o b j e c t , h e i g h t 2 9 c m _ c o u r t e s y o f C o l l e z i o n e Z a t t o n i<br />

Introduction<br />

_ 1

artists<br />

2_<br />

Artists<br />

•<br />

•<br />

• Abakanowicz Magdalena (Poland) born 1930 in Falenty, lives and works in Warsaw<br />

• Abramović Marina (Serbia) born 1946 in Belgrade, lives and works in Amsterdam and New York<br />

• Agolli Rovena (Albania) born 1976 in Tirana, lives and works in Monterey, USA<br />

• Anđelić-Galić Gordana (Bosnia and Herzegovina) born 1949 in Mostar, lives and works in Sarajevo<br />

• Antoshina Tatyana (Russia) born 1959 in Krasnoyarsk, lives and works in Moscow<br />

• Arakelyan Anita (Armenia) born 1964 in Yerevan, lives and works in Yerevan<br />

• Arevshatyan Arevik (Armenia) born 1957 in Yerevan, lives and works in Yerevan<br />

• Baba Corneliu (Romania) 1906–1997. Born in Craiova, Romania, lived and worked in Bucharest<br />

• Bajević Maja (Bosnia and Herzegovina) born 1967 in Sarajevo, lives and works in Sarajevo, Berlin<br />

and Paris<br />

• Balčus Arnis (Latvia) born 1978 in Riga, lives and works in Riga and London<br />

• Baranovici Ana (Moldova) 1906–2001. Born in Tighina, lived and worked in Chişinãu<br />

• Bartuszová Mária (Slovakia) 1936–1996. Born in Prague, lived and worked in Prague<br />

• Vika Begalska (Ukraina) born 1975 w Dnepropietrowsk, lives and works in Moscow<br />

• Benczúr Emese (Hungary) born 1969 in Budapest, lives and works in Budapest<br />

• Beqiri Sokol (Kosovo) born 1964 in Pejë, lives and works in Pejë<br />

• Bereś Jerzy (Poland) born 1930 in Nowy Sącz, lives and works in Cracow<br />

• Berhidi Mária (Hungary) born 1953 in Budapest, lives and works in Budapest<br />

• Bočkayová Klára (Slovakia) born 1948 in Martin, lives and works in Bratislava and Stupava<br />

• Brǎtescu Geta (Romania) born 1926 in Ploieşti, lives and works in Bucharest<br />

• Brendel Micha (Germany) born 1959 in Weida / Thüringen, lives and works in Berlin<br />

• Brković Ozana (Montenegro) born 1975 in Podgorica, lives and works in Podgorica<br />

• Bromová Veronika (Czech Republic) born 1966 in Prague, lives and works in Prague<br />

• Bubelytė Violeta (Lithuania) born 1956 in Vilnius, lives and works in Vilnius<br />

• Čapovska Violeta (Macedonia) born 1967 in Skopje, lives and works in Melbourne<br />

• Chernysheva Olga (Russia) born 1962 in Moscow, lives and works in Moscow<br />

• Chisa Anetta Mona (Slovakia) born 1975 in Nadlak, Romania, lives and works in Bratislava and Prague<br />

• Chkadua Eteri (Georgia) born 1965 in Tbilisi, lives and works in New York; Kingston, Jamaica<br />

and Tbilisi<br />

• Chogoshvili Levan (Georgia) born 1953 in Tbilisi, lives and works in Tbilisi<br />

• Croitoru Alexandra (Romania) born 1975 in Bucharest, lives and works in Bucharest<br />

• C.U.K.T (Poland) Robert Mikołaj Jurkowski, Maciej Sienkiewicz, Rafał Ewertowski, Jacek Niegoda,<br />

Piotr Wyrzykowski, Artur Kozdrowski (established in 1995, acts in Gdańsk)<br />

• Daučíková Anna (Slovakia) born 1950 in Bratislava, lives and works in Bratislava<br />

• Delimar Vlasta (Croatia) born 1956 in Zagreb, lives and works in Zagreb<br />

• Dér András (Hungary) born 1954 in Budapest, lives and works in Budapest<br />

• Dopitová Milena (Czech Republic) born 1963 in Sternberk, lives and works in Prague<br />

• Drozdik Orshi (Hungary) born 1946 in Abda, lives and works in Budapest and New York<br />

• Dzividzinska Zenta (Latvia) born 1944 in the district of Code, lives and works in Riga<br />

• Eperjesi Ágnes (Hungary) born 1964 in Budapest, lives and works in Budapest<br />

• Falender Barbara (Poland) born 1947 in Wrocław, lives and works in Warsaw<br />

• Fangor Wojciech (Poland) born 1922 in Warsaw, lives and works in Warsaw<br />

• Filová Eva (Slovakia) born 1968 in Bratislava, lives and works in Bratislava<br />

• Fischer Vera (Croatia) 1925–2009. Born in Zagreb, lived and worked in Zagreb<br />

• Gábor Imre (Hungary) born 1960 in Dunaújváros, lives and works in Budapest<br />

• Gabriel Else (Germany) born 1962 in Halberstadt, lives and works in Berlin<br />

• Galántai György (Hungary) born 1941 in Bikacs, lives and works in Budapest<br />

• Gelguda Ugnius (Lithuania) born 1977 in Vilnius, lives and works in Vilnius<br />

• Gerlovina Rimma (Russia) born 1951 in Moscow, lives and works in New York<br />

• Gerlovin Valery (Russia) born 1945 in Moscow, lives and works in New York<br />

• Georgieva Alla (Bulgaria) born 1957 in Kharkov, Ukraine, lives and works in Sofia<br />

• Gorlova Lyudmila (Russia) born 1968 in Moscow, lives and works in Moscow<br />

• Górna Katarzyna (Poland) born 1968 in Warsaw, lives and works in Warsaw<br />

• Gotovac Tomislav (Croatia) born 1937 in Sombor, Serbia, lives and works in Zagreb<br />

• Grigorescu Ion (Romania) born 1945 in Bucharest, lives and works in Bucharest<br />

• Grīnbergs Andris (Latvia) born 1946 in Riga, lives and works in Riga<br />

• Group F.F.F.F. (Estonia) Kaire Rannik, Kristi Paap, Berit Teeäär, Ketli Tiitsar, Maria Valdma<br />

1996–2005, members of the group live and work in Tallinn<br />

• Grubić Igor (Croatia) born 1969 in Zagreb, lives and works in Zagreb<br />

• Gržinić Marina (Slovenia) born 1958 in Rijeka, Croatia, lives and works in Ljubljana and Vienna<br />

• Gustowska Izabella (Poland) born 1948 in Poznań, lives and works in Poznań<br />

• Gyenis Tibor (Hungary) born 1970 in Pécs, lives and works in Budapest<br />

• Hadžifejzović Jusuf (Bosnia and Herzegovina) born 1956 in Prijepolje, Serbia, lives and works in<br />

Sarajevo and Antwerp<br />

• Hajas Tibor (Hungary) 1946–1980. Born in Budapest, lived and worked in Budapest<br />

• Hampel Angela (Germany) born 1956 in Räckelwitz, lives and works in Dresden<br />

• Harxhi-Koci Merita (Kosovo) born 1969 in Pejë, lives and works in Prishtina<br />

• Heinrihsone Helēna (Latvia) born 1948 in Riga, lives and works in Riga<br />

• Iltnere Ieva (Latvia) born 1957 in Riga, lives and works in Riga<br />

• Iveković Sanja (Croatia) born 1949 in Zagreb, lives and works in Zagreb<br />

• Jabłońska Elżbieta (Poland) born 1970 in Olsztyn, lives and works in Bydgoszcz<br />

• Kalentz Armine (Armenia) 1920–2007, lived and worked in Yerevan, Aleppo, Syria and Beirut, Lebanon<br />

• Kaljo Kai (Estonia) born 1959 in Tallinn, lives and works in Tallinn<br />

• Kamerić Šejla (Bosnia and Herzegovina) born 1976 in Sarajevo, lives and works in Sarajevo<br />

and Berlin<br />

• Keserü Ilona (Hungary) born 1933 in Pécs, lives and works in Pécs<br />

• Khomenko Olesya (Ukraine) born 1980 in Kiev, lives and works in Kiev<br />

• Kobro Katarzyna (Poland) 1898–1951. Born in Moscow, lived and worked in Łódź<br />

• Kobzdej Aleksander (Poland) 1920–1972. Born in Olesko, Ukraine, lived and worked in Warsaw<br />

• Kolářová Běla (Czech Republic) born 1923 in Terezin, lives and works in Prague and Paris<br />

• Korņetskis Mihails (Latvia) 1926–2005, lived and worked in Riga<br />

• Korolkiewicz Łukasz (Poland) born 1948 in Warsaw, lives and works in Warsaw<br />

• Kovshar Anna (Belarus) born 1977 in Minsk, lives and works in Minsk and Prague<br />

• Kovylina Elena (Russia) born 1971 in Moscow, lives and works in Moscow<br />

• Kozyra Katarzyna (Poland) born 1963 in Warsaw, lives in Warsaw and Berlin<br />

• Krasauskas Stasys (Lithuania) 1929–1977. Born in Kaunas, lived and worked in Vilnius<br />

• Krašovec Metka (Slovenia) born 1941 in Ljubljana, lives and works in Ljubljana<br />

• Kulik Zofia (Poland) born 1947 in Wrocław, lives and works in Łomianki<br />

• Kuryluk Ewa (Poland) born 1946 in Krakow, lives and works in Paris<br />

• Ladik Katalin (Serbia) born 1942 in Novi Sad, lives and works in Budapest<br />

• Lahovsky Stjepan (Croatia) 1902–1989. Born in Donji Miholjac, lived and worked in Zagreb<br />

• Lapin Leonhard (Estonia) born 1947 in Räpina, lives and works in Tallinn<br />

• Lehocká Denisa (Slovakia) born 1971 in Trenčín, lives and works in Bratislava<br />

• Liankevich Andrei (Belarus) born 1981 in Grodno, lives and works in Minsk<br />

• Libera Zbigniew (Poland) born 1959 in Pabianice, lives and works in Prague and Warsaw<br />

• LN Women’s League (Latvia) LN sieviešu līga (Latvian National Women’s League Project) was founded<br />

in 1997. Curator of the Project: Inga Šteimane. Members: Ingrīda Zābere, Ilze<br />

Breidaka, Kristīne Keire, Izolda Cēsniece, Silja Pogule<br />

• Logar Lojze (Slovenia) born 1944 in Mežica, lives and works in Ljubljana<br />

• Logina Zenta (Latvia) 1908–1983. Born in Riga, lived and worked in Riga<br />

• Makhukov Oleksandr (Ukraine) 1911–1996. Born in Lugansk, lived and worked in Lugansk<br />

• Māliņa Sarmīte (Latvia) born 1960 in Anīkste, lives and works in Riga<br />

• Maliqi Dren (Kosovo) born 1981 in Prishtina, lives and works in Prishtina<br />

• Mamyshev-Monroe Vladislav (Russia) born 1969 in Leningrad, lives and works in Moscow<br />

• Mamzeta Monika (Poland) born 1972 in Warsaw, lives and works in Warsaw<br />

• Margit Anna (Hungary) 1913–1991. Born in Budapest, lived and worked in Budapest<br />

• Martek Vlado (Croatia) born 1951 in Zagreb, lives and works in Zagreb<br />

• Marušič Živko (Slovenia) born 1945 in Colorno, Italy, lives and works in Koper<br />

• Matić Goranka (Serbia) born 1949 in Maribor, Slovenia, lives and works in Belgrade<br />

• Mattheuer Wolfgang (Germany) 1927–2004. Born in Reichenbach / Vogtland, lived and worked in Leipzig<br />

• Maurer Dóra (Hungary) born 1937 in Budapest, lives and works in Budapest and Vienna<br />

• Michelkevičiūtė Snieguolė (Lithuania) born 1953 in Kaunas, lives and works in Kaunas<br />

• Mikhailov Boris (Ukraine) born 1938 in Kharkov, lives and works in Berlin and Kharkov<br />

• Mlčoch Jan (Czech Republic) born 1953 in Prague, lives and works in Prague<br />

• Modzelewski Jarosław (Poland) born 1955 in Warsaw, lives and works in Warsaw<br />

• Mozūraitė-Klemkienė Jadvyga (Lithuania) born 1923 in Kaunas, lives and works in Kaunas<br />

• Mulliqi Muslim (Kosovo) 1934–1998. Born in Gjakova, lived and worked in Prishtina<br />

• Mujezinović Ismet (Bosnia and Herzegovina) 1907–1984. Born in Tuzla, lived and worked in Tuzla<br />

• Mutsu Marju (Estonia) 1941–1980. Born in Tallinn, lived and worked in Tallinn<br />

• Natalia LL (Lach Lachowicz) (Poland) born 1937 in Żywiec, lives and works in Wrocław<br />

• Nagy Kriszta (Hungary) born 1972 in Szolnok, lives and works in Budapest<br />

• Neagu Paul (Romania) 1938–2004. Born in Bucharest, lived and worked in London<br />

• Németh Hajnal (Hungary) born 1972 in Szony, lives and works in Berlin<br />

• Németh Ilona (Slovakia) born 1963 in Dunajská Streda, lives and works in Dunajská Streda<br />

• Nerkararyan Arax (Armenia) born 1960 in Gyumri, lives and works in Gyumri/Yerevan<br />

• Niesiołowski Tymon (Poland) 1882–1965. Born in Lwow, Ukraine, lived and worked in Vilnius and Thorn<br />

• Nikšić Damir (Bosnia and Herzegovina) born 1970 in Sarajevo, lives and works in Stockholm<br />

• OHO Group (Slovenia) David Nez, Milenko Matanovič, Drago Dellabernardina, 1966–1971, acted<br />

in Ljubljana<br />

• Ostojić Tanja (Serbia) born 1972 in Užice, lives and works in Berlin<br />

• Pągowska Teresa (Poland) 1926–2007. Born in Warsaw, lived and worked in Warsaw<br />

• Paripović Neša (Serbia) born 1942 in Belgrade, lives and works in Belgrade<br />

• Partum Ewa (Poland) born 1945 in Grodzisk Mazowiecki, lives and works in Berlin<br />

• Pauer Gyula (Hungary) born 1941 in Budapest, lives and works in Budapest<br />

• Pauļuka Felicita (Latvia) born 1925 in Riga, lives and works in Riga<br />

• Pavićević Milija (Montenegro) born 1950 in Cetinje, lives and works in Cetinje<br />

• Perjovschi Lia (Romania) born 1961 in Sibiu, lives and works in Bucharest<br />

• Petrović Zora (Serbia) 1894–1962. Born in Dobrica, lived and worked in Belgrade<br />

• Petrova Galina (Lithuania) born 1927 in Astrakhan, Russia, lives and works in Vilnius<br />

• Pinińska-Bereś Maria (Poland) 1931–1999. Born in Poznań, lived and worked in Kraków<br />

• Põder Anu (Estonia) born 1947 in Kanepi, lives and works in Tallinn<br />

• Pogačar Tadej (Slovenia) born 1960 in Ljubljana, lives and works in Ljubljana<br />

• Preda Sânc Marilena (Romania) born 1955 in Bucharest, lives and works in Bucharest<br />

• Prvulović Nadežda (Serbia) born 1930 in Dubrovnik, Croatia, lives and works in Richmond and<br />

New York<br />

• Qehaja Nurhan (Kosovo) born 1981 in Prishtina, lives and works in Prishtina<br />

• Radić Jelena (Serbia) born 1978 in Pančevo, lives and works in Belgrade<br />

• Raidpere Mark (Estonia) born 1975 in Tallinn, lives and works in Tallinn<br />

• Rakauskaitė Eglė (Lithuania) born 1967 in Vilnius, lives and works in Vilnius<br />

• RASSIM (Bulgaria) born 1972 in Orehovitsa, lives and works in Sofia<br />

• Rosenstein Erna (Poland) 1913–2004. Born in Lwow lived and worked in Kraków and Warsaw<br />

• Rossa Boryana (Bulgaria) born 1972 in Sofia, lives and works in Sofia and Troy, USA<br />

• Rousseva Lilyana (Bulgaria) 1932–2009. Born in Ruse, lived and worked in Sofia<br />

• Roussev Svetlin (Bulgaria) born 1933 in Pleven, lives and works in Sofia<br />

• Rožanskaitė Marija Teresė (Lithuania) 1933–2007. Born in Linkuva, lived and worked in Vilnius<br />

• Runge Sirje (Estonia) born 1950, lives and works in Tallinn<br />

• Rusu-Ciobanu Valentina (Moldova) born 1920 in Chişinãu, lives and works in Chişinãu<br />

• Sadovskaia Varvara (Moldova) born 1922 in Suhaya Greblya, Ukraine, lives and works in Chişinãu<br />

and St. Petersburg<br />

• Ságlová Zorka (Czech Republic) 1942–2003. Born in Humpolec, lived and worked in Prague<br />

• Sakulowski Horst (Germany) born 1943 in Saalfeld, lives and works in Weida<br />

• Sala Anri (Albania) born 1974 in Tirana, lives and works in Paris and Berlin<br />

• Šaltenis Arvydas (Lithuania) born 1944 in Klevėnai, lives and works in Vilnius<br />

• Sambolec Duba (Slovenia) born 1949 in Ljubljana, lives and works in Trondheim, Norway<br />

• Sauka Šarūnas (Lithuania) born 1958 in Vilnius, lives and works in Dusetos, Lithuania<br />

• Schlegel Christine (Germany) born 1950 in Crossen, lives and works in Dresden<br />

• Schleime Cornelia (Germany) born 1953 in Berlin (East), lives and works in Berlin<br />

• Shkololli Erzen (Kosovo) born 1976 in Pejë, lives and works in Prishtina and Berlin<br />

• Šimotová Adriena (Czech Republic) born 1926 in Prague, lives and works in Prague<br />

• Sinkó Károly (Hungary) 1910–1967. Born in Budapest, lived and worked in Budapest<br />

• Skade Fritz (Germany) 1898–1971. Born in Döhlen near Dresden, lived and worked in Dresden<br />

• Skudutis Mindaugas (Lithuania) born 1948 in Antagavė, lives and works in Vilnius<br />

• Skulme Džemma (Latvia) born 1925 in Riga, lives and works in Riga<br />

• Šmid Aina (Slovenia) born 1957 in Ljubljana, lives and works in Ljubljana<br />

• Sobczyk Marek (Poland) born 1955 in Warsaw, lives and works in Warsaw<br />

• Šonta Virginijus (Lithuania) 1952–1992. Born in Panevėžys, lived and worked in Kaunas and Vilnius<br />

• Stančič Zora (Slovenia) born 1956 in Štrbe, Bosnia and Hercegovina, lives and works in Ljubljana<br />

• Stilinović Sven (Croatia) born 1956 in Zagreb, lives and works in Rijeka<br />

• Stötzer Gabriele (Germany) born 1953 in Emleben, lives and works in Erfurt and Utrecht<br />

• Stupica Gabrijel (Slovenia) 1913–1990. Born in Dražgoše, lived and worked in Ljubljana<br />

• Szabó Ágnes (Hungary) born 1969 in Győr, lives and works in Budapest<br />

• Szapocznikow Alina (Poland) 1926–1973. Born in Kalisz, lived and worked in Paris<br />

• Szenes Zsuzsa (Hungary) 1931–2001. Born in Budapest, lived and worked in Budapest<br />

• Szépfalvi Ágnes (Hungary) born 1965 in Budapest, lives and works in Budapest<br />

• Szilas Győző (Hungary) 1921–1998. Born in Újpest, lived and worked in Budapest<br />

• The Factory of Found Clothes (Russia) Gluklya — Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya born 1968 in Leningrad,<br />

Tsaplya — Olga Egorova born 1968 in Khabarovsk, founded in 1996 by Gluklya.<br />

They live and work in St. Petersburg<br />

• Tihemets Evi (Estonia) born 1932 in Tapa, lives and works in Tallinn<br />

• Tkáčová Lucia (Slovakia) born 1977 in Banská Štiavnica, lives and works in Bratislava<br />

• Todosijević Raša (Serbia) born 1945 in Belgrade, lives and works in Belgrade<br />

• Tolj Slaven (Croatia) born 1964 in Dubrovnik, lives and works in Dubrovnik<br />

• Tomašević Jelena (Montenegro) born 1974 in Podgorica, lives and works in Podgorica<br />

• Tomić Milica (Serbia) born 1960 in Belgrade, lives and works in Belgrade<br />

• Tralla Mare (Estonia) born 1967 in Tallinn, lives and works in Tallinn and London<br />

• Ujj Zsuzsi (Hungary) born 1959 in Veszprém, lives and works in Budapest<br />

• Urbonas Gediminas (Lithuania) born 1966 in Vilnius, lives and works in Vilnius; Trondheim, Norway<br />

and Boston<br />

• Urbonas Nomeda (Lithuania) born 1968 in Kaunas, lives and works in Vilnius; Trondheim, Norway<br />

and Boston<br />

• Vainstein Moysey (Ukraine) 1940–1981 born in Donetsk region, lived and worked in Kiev<br />

• Vangeli Žaneta (Macedonia) born 1963 in Bitola, lives and works in Skopje<br />

• Varl Petra (Slovenia) born 1965 in Ljubljana, lives and works in Ljubljana and Maribor<br />

• Vashkevich Ruslan (Belarus) born 1966 in Minsk, lives and works in Minsk<br />

• Válová Jitka (Czech Republic) born 1922 in Kladno, lives and works in Kladno<br />

• Veiverytė Sofija (Lithuania) 1926–2009. Born in Naujatrobiai, lived and worked in Vilnius<br />

• Vesović Mio (Croatia) born 1953 in Gornja Dobrinja, lives and works in Zagreb<br />

• Woisnitza Karla (Germany) born 1952 in Rüdersdorf, lives and works in Berlin<br />

• Wójcik Julita (Poland) born 1971 in Gdańsk, lives and works in Gdańsk<br />

• Womacka Walter (Germany) born 1925 in Obergeorgenthal, Czech Republic, lives and works in Berlin<br />

• Yudin Oleksandr (Ukraine) born 1934 in Moscow, Russia, lives and works in Kiev<br />

• Zaretzky Viktor (Ukraine) 1925–1990. Born in Sumy region, lived and worked in Kiev<br />

• Zariņa Aija (Latvia) born 1954 in Saukas of Jēkabpils, district, lives and works in Riga<br />

• Zariņš Indulis (Latvia) 1929–1997. Born in Riga, lived and worked in Riga<br />

• Żebrowska Alicja (Poland) born 1956 in Zakopane, lives and works in Kraków<br />

• Želibská Jana (Slovakia) born 1941 in Olomouc, Czech Republic, lives and works in Bratislava<br />

• Ziegler Doris (Germany) born 1949 in Weimar, lives and works in Leipzig<br />

• Žvegelj Janja (Slovenia) born 1967 in Ljubljana, lives and works in Ljubljana

I Floor_<br />

1_<br />

2_<br />

3_<br />

4_<br />

pArt II_<br />

GEndEr ChECk.<br />

FEMInInIty<br />

And MAsCulInIty<br />

In thE Art<br />

oF EAstErn EuropE_<br />

pArt I<br />

<strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Check</strong> is the first comprehensive<br />

survey of Eastern<br />

European art dealing with gender<br />

roles. Showcasing more than 200<br />

artists, who employ a variety of<br />

media, and covering a time-span<br />

of about half a century, <strong>Gender</strong><br />

<strong>Check</strong> paints a diverse picture of<br />

a chapter of art history which<br />

until now has remained largely<br />

unknown.<br />

Twenty years after the fall of the<br />

Berlin Wall, the exhibition traces<br />

the changes in the representation<br />

of male and female gender<br />

roles via thematically organized<br />

sections. In early examples of<br />

Social Realistic art the ‘heroes<br />

and heroines of labour’ are<br />

practically ubiquitous. These<br />

depictions of male and female<br />

workers illustrate the communist<br />

rulers’ claim that they were<br />

building a gender-neutral society<br />

— a claim that in unofficial art<br />

from that period is exposed as<br />

a lie. After an era dominated by<br />

the collective utopian visions<br />

imposed by the state, there<br />

followed a long period — lasting<br />

right up to the end of communism<br />

— when, with many<br />

regional differences and hobbled<br />

by a great many setbacks,<br />

individualism and liberalism<br />

found precarious footholds,<br />

pArt III_<br />

making possible the free spaces<br />

required for non-conformist art<br />

to flourish. From the 1970s on,<br />

this growing self-confidence is<br />

reflected in a new focus on the<br />

body and in an openly flaunted<br />

sexuality that calls into question<br />

heterosexual norms and heroic<br />

ideals of masculinity. With the<br />

fall of the Berlin Wall and the<br />

subsequent ascendancy of consumerism,<br />

new freedoms were<br />

gained which, however, were accompanied<br />

by neo-conservative<br />

constraints with regard to gender<br />

roles. Chauvinism, militarism<br />

and hostility towards minorities<br />

are some of the negative facets<br />

of the post-communist era that<br />

the artists presented here cast<br />

a critical light on.<br />

1_prIVAtE rEAlItIEs,<br />

pErsonAl rEsIstAnCEs<br />

The family with its inherent<br />

heterosexual normativity is a<br />

topic much favoured by official<br />

socialism. Where those artists<br />

who were excluded from the<br />

official art discourse did address<br />

this issue at all, they tended<br />

to set off the private, domestic<br />

sphere against the gender<br />

roles imposed by the state. A<br />

critical stance towards socialist<br />

power and communist ideology<br />

could also find an outlet in the<br />

deconstruction of the official<br />

rituals by means of which the<br />

state celebrated itself. The artists<br />

1_ 2_ 3_<br />

cast a bilious glance at stateorganized<br />

mass events or they<br />

take up a decidedly anti-militarist<br />

position, pointing out the<br />

problematic nature of the army<br />

and the madness of the arms race.<br />

2_hEroInEs oF Work:<br />

EMAnCIpAtIon<br />

And dIsContEnt<br />

Ever since the days of the October<br />

Revolution, women’s liberation<br />

occupied a prominent place on<br />

the communist agenda. When<br />

after the end of World War II the<br />

communist parties seized power<br />

in the countries of Eastern Europe,<br />

women’s position in society was<br />

improved in various ways. Yet despite<br />

bringing in a number of<br />

seminal laws — women’s right to<br />

vote, equal rights at work, access<br />

to (higher) education and paid<br />

maternity leave — the communist<br />

rulers did not get even close to<br />

resolving the ‘women question’.<br />

The exhibition features a number<br />

of paintings extolling women<br />

as ‘heroines of socialist labour’.<br />

Other works, however, suggest<br />

that even though a new age<br />

seemed to be dawning as far as<br />

women’s political and economic<br />

status was concerned, things did<br />

not in truth change all that much.<br />

Thus, in some of the exhibits<br />

a discontent about having from<br />

now on to carry the double burden<br />

of public and domestic work finds<br />

eloquent expression.<br />

1_Boris Mikhailov (Ukraine), from the Suzi et cetera cycle, 1960s’, photograph, courtesy of the artist © VBK Wien, 2009<br />

2_Michails Korneckis (Latvia), Let’s Go Girls, 1959, oil on canvas, coll. The Latvian National Museum of Art, Riga © Normundus Braslins<br />

3_Wojciech Fangor (Poland), Figures, 1950, oil on canvas, coll. Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi © Wojciech Fangor<br />

4_Galina Petrova (Lithuania), Women, Cleaning Fish, 1969, synthetic tempera on canvas, coll. Lithuanian Art Museum, Vilnius © Galina Petrova<br />

5_Sanja Iveković (Croatia), Personal Cuts, 1982, video, 3’40”, coll. Generali Foundation Collection, Wien © Sanja Iveković<br />

pArt I_<br />

_soCIAlIst<br />

IConosphErE<br />

3_WoMEn At Work,<br />

MEn At Work<br />

The first section of the exhibition<br />

comprises works dealing with<br />

various aspects of everyday life<br />

and social reality in early state<br />

socialism. In the late 1940s,<br />

when the communist regimes<br />

in Eastern Europe were already<br />

firmly established, the new rulers<br />

set out to combat traditional<br />

gender structures by introducing<br />

a number of egalitarian policies.<br />

Thus, women were encouraged<br />

to enter professions that until<br />

then had been exclusively male<br />

domains. The ideal of a genderneutral<br />

working environment<br />

of work was duly celebrated in<br />

a number of ‘official’ paintings<br />

in which men and women could<br />

be seen working harmoniously<br />

side by side. It was during the<br />

era of Socialist Realism that this<br />

utopian vision had its heyday,<br />

but it lived on all through the<br />

1970s. Yet the paintings and<br />

sculpture of socialist realism do<br />

not only testify to the special value<br />

accorded to labour in socialist<br />

societies. The sheer diversity in<br />

the depiction of their protagonists<br />

also provides evidence that in<br />

spite of all the efforts made by the<br />

communist authorities they did<br />

not quite succeed in establishing<br />

homogenous, one-size-fits-all<br />

models of femininity and<br />

masculinity.<br />

4_<br />

5_<br />

4_rEMAkInG thE pAst<br />

AFtEr 1989<br />

After 1989, the socialist past was<br />

revised or completely rewritten<br />

in paintings, photographs and<br />

videos. In some of these works,<br />

the past is seen through the lens<br />

of autobiography, family histories<br />

and childhood memories. In<br />

others, the communist army discipline<br />

is made a laughing-stock<br />

of by showing naked soldiers who<br />

indulge in dancing and heavy<br />

drinking. Some works aim at exposing<br />

the oppressive role played<br />

by the state apparatus with its<br />

methods of surveillance, control<br />

and persecution. The wars in<br />

ex-Yugoslavia and the disintegration<br />

of this state form the subject<br />

of videos that juxtapose images<br />

of a peaceful past with images<br />

of the catastrophes wrought<br />

by war-mongering ideologists.<br />

Another thematic section is<br />

about female anti-fascist activists<br />

and partisans who died in World<br />

War II: celebrated as national<br />

saints under communism, they<br />

were cast into collective oblivion<br />

after 1989.<br />

_Socialist Iconosphere<br />

_ 3

I Floor_<br />

_Negotiating Personal Spaces<br />

4_<br />

pArt I_<br />

5_<br />

6_<br />

7_<br />

GEndEr ChECk.<br />

FEMInInIty<br />

And MAsCulInIty<br />

In thE Art<br />

oF EAstErn EuropE_<br />

pArt II<br />

In the 1970s and 80s many artists<br />

turned to exploring the private<br />

sphere, a withdrawal that is both<br />

symptom of and comment on the<br />

social reality they were confronted<br />

with. While painting certainly remained<br />

the most popular medium,<br />

the growing importance of body<br />

art and performances was accompanied<br />

by an increased interest in<br />

photography, film and video both<br />

as artistic and documentary media.<br />

These technologies were often<br />

used to underline the processual<br />

aspect of art and call into question<br />

the time-honoured notion of the<br />

autonomous and self-contained<br />

work of art.<br />

5_rEprEsEntInG<br />

WoMEn: lAtEnt<br />

FEMInIsM Vs. old<br />

stErEotypEs<br />

The emancipation from the<br />

traditional media made it possible<br />

to redefine femininity with<br />

complete disregard for the then<br />

prevalent norms of representation.<br />

The artists increasingly turn to<br />

the private sphere which to many<br />

was the only space of freedom.<br />

While some of the works exhibited<br />

here reproduce the old, socially<br />

constructed stereotypes of an ideal<br />

femininity, other, more progressive<br />

positions are informed by what<br />

one might call a gentle feminist<br />

resistance. Only very few artists<br />

working in that period opted for<br />

taking up a decidedly feminist<br />

8_<br />

pArt III_<br />

pArt III_<br />

stance. The subject of motherhood<br />

is treated in an intimate, sober,<br />

non-heroic manner, while female<br />

sexuality is seen from a fresh<br />

perspective that breaks with the<br />

cliché of female passivity. Portraits<br />

of both male and female friends<br />

from the art scene give us access<br />

to the artists’ immediate personal<br />

environment. In connection with<br />

a newly awakened self-confidence,<br />

the female nude became a central<br />

point of reference. The fact that in<br />

circles that remained loyal to the<br />

communist state the female nude<br />

was still regarded as the epitome<br />

of an ideal femininity makes the<br />

shift from the male to the female<br />

gaze appear all the more radical.<br />

6_polItICs oF<br />

sElF-rEprEsEntAtIon<br />

Historically, the genre of the<br />

self-portrait has always been the<br />

male artist’s medium of choice for<br />

asserting his identity as sovereign<br />

creator or tortured soul — a legacy<br />

that many male artists working<br />

under state socialism were the<br />

uncritical inheritors of. It is therefore<br />

quite fascinating to observe<br />

the strategies deployed by women<br />

artists in appropriating this genre<br />

and in subverting androcentric<br />

definitions of self-representation.<br />

Here, the self-portrait is not a mirror<br />

that accurately and naturalistically<br />

reflects a static self. For<br />

the women artists displayed here,<br />

the self-portrait rather serves as<br />

a means to constitute themselves<br />

as professional subjects, as artists.<br />

Moreover, these self-portraits<br />

throw a light on the various ways<br />

in which women could answer<br />

the challenge presented by the<br />

complex bundle of gender-coded<br />

roles ascribed to and imposed<br />

upon them. Reactions range<br />

from a militantly expressed<br />

commitment to female sexuality<br />

to a more detached, objective<br />

perspective on the female body.<br />

7_WoMEn ArtIsts<br />

ApproprIAtE<br />

‘unIVErsAl Art’<br />

In most communist countries it<br />

was only after a long and painful<br />

process that abstract art could<br />

eventually find some degree of<br />

acceptance. The 1950s and 60s<br />

witnessed a series of polemics<br />

against abstract art, which was<br />

criticized as ‘formalistic’ and,<br />

worse even, denounced as a cultural<br />

import from the capitalist<br />

west. Yugoslavia was an important<br />

exception in that after the break<br />

with Stalin (1948) abstractionism<br />

was soon embraced as the official<br />

art ideology. The other exception<br />

was Poland, where abstract art<br />

was at least tolerated by the rulers.<br />

For the female artists shown here,<br />

abstractionism was a universal<br />

language that enabled them to<br />

articulate humanist ideals and to<br />

confirm their artistic subjectivity<br />

and freedom. Here, too, they<br />

entered a field that until then had<br />

been the exclusive domain of the<br />

‘male genius’. In these abstract,<br />

non-figurative works one can<br />

make out a variety of subtexts and<br />

hidden sexual and erotic meanings,<br />

so that with hindsight these<br />

examples of supposedly ‘pure’<br />

abstract art appear to be rather<br />

‘crypto-iconic’.<br />

6_ 7_ 8_<br />

10_<br />

9_<br />

8_CouplEs,<br />

rElAtIonshIps, loVEs<br />

The immediate personal environment<br />

of men and women artists<br />

is at the heart of works concerned<br />

with hetero- and homosexual<br />

relationships among the protagonists<br />

of the art scene. Many of the<br />

exhibits shown here hark back to<br />

the classic topos of the artist and<br />

the model, yet in some of them<br />

the traditional assignment of<br />

roles — male artist versus female<br />

model-cum-muse — is rejected.<br />

The subject of love usually follows<br />

a strictly heterosexual pattern,<br />

but the works dealing with samesex<br />

relationships call the validity<br />

of this matrix into question.<br />

While some of the artists incline<br />

toward a slightly romanticized<br />

perspective, others tend to<br />

emphasize the darker sides of<br />

human relationships.<br />

9_hEroIC MAlE<br />

subjECt rEConsIdErEd<br />

Alternative representations<br />

of masculinity undermine the<br />

model of the male hero as it was<br />

promulgated in ‘official’ painting<br />

and sculpture. They also make<br />

a wry comment on the militarism<br />

and the arms race that were such<br />

essential aspects of the cold war<br />

era. The exhibits try to capture<br />

men’s everyday life, moments<br />

of normality. While some artists<br />

use the genre of the portrait,<br />

others explore their masculinity<br />

in a more direct manner trough<br />

performances in which they act as<br />

anti-heroes. In the socialist societies,<br />

the male nude never gained<br />

as much recognition as the female<br />

nude. Maleness as defined by<br />

6_Izabella Gustowska (Poland), Sacrifice I — from the Relative Similarities cycle, 1989–1990, mixed media on canvas, coll. Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu © Izabella Gustowska<br />

7_Andris Grīnbergs (author of performance), Andrejs Grants (author of photographs) (Latvia), Model and Others, 1988, documentation of performance, photograph, courtesy of the artists © Andris Grīnbergs<br />

8_Marina Abramović (Serbia), Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful, 1975, video, 13’48”, coll. Netherlands Media Institute, Montevideo © Marina Abramović<br />

pArt II_<br />

_nEGotIAtInG<br />

pErsonAl<br />

spACEs<br />

socialism always meant heterosexual<br />

maleness. Homosexuality<br />

was punished as a crime. Thus it<br />

does not come as a surprise that<br />

only very few works dating from<br />

the era of socialism examine<br />

homosexual aspects of maleness.<br />

10_pErForMInG<br />

GEndEr / pErForMInG<br />

thE sElF<br />

When concept art flourished in<br />

the 1970s, many Eastern European<br />

artists (like their counterparts in<br />

the West) began using the new<br />

media in order to explore their<br />

body, their sexuality and their<br />

individuality. All the works shown<br />

here were conceived as series. The<br />

serial nature characterizing these<br />

works not only heightens the<br />

viewer’s awareness of the passing<br />

of time, it also draws attention to<br />

their processual and performative<br />

aspect. The break with traditional<br />

forms of representation and outdated<br />

subject matters is reflected<br />

in the rejection of conventional<br />

artistic genres such as painting or<br />

sculpture. Provisionality and transitoriness<br />

are the new yardsticks<br />

by whose measure the notion<br />

of the autonomous work of art<br />

encapsulating timeless truths<br />

is found wanting.

pArt I_<br />

I Floor_<br />

GEndEr ChECk.<br />

FEMInInIty<br />

And MAsCulInIty<br />

In thE Art<br />

oF EAstErn EuropE_<br />

pArt III<br />

The fall of the Berlin Wall, the disintegration<br />

of the communist regimes<br />

in East and Central Europe and the<br />

USSR, the establishment of the new<br />

states in the early 1990s — all these<br />

historic events shaped an era which<br />

has aptly been called ‘the age of<br />

Lenin in ruins’. The introduction of<br />

liberal democracy and multiparty<br />

systems in these countries went<br />

hand in hand with the introduction<br />

of (or return to) capitalist modes of<br />

production. The post-communist<br />

economic transition period of the<br />

1990s caused mass unemployment,<br />

especially among women, and led<br />

to pauperization on a large scale. In<br />

fact, the social fabric of these new<br />

democratic societies underwent<br />

a rapid process of economic polarization<br />

resulting in the chasm that<br />

today divides the nouveaux riches<br />

from the nouveaux pauvres.<br />

These social transformations<br />

have been critically reflected by<br />

Eastern European artists. The works<br />

displayed in this section of the<br />

exhibition are all informed by such<br />

a critical (sometimes even cynical)<br />

attitude. The artists here presented<br />

deconstruct the nationalist and<br />

neo-conservative value systems<br />

that have made a comeback in the<br />

post-socialist societies. They try<br />

to make visible the interfaces and<br />

affinities between hierarchically<br />

9_<br />

11/12_<br />

11/12_<br />

13_<br />

_ stAIr-<br />

CAsE<br />

pArt II_<br />

Ground Floor_<br />

14_<br />

15_<br />

15_<br />

structured roles and a social order<br />

dominated by capitalism.<br />

11_thE polItICIzAtIon<br />

oF thE prIVAtE<br />

In the 1990s, we first encounter art<br />

that is openly feminist as well as<br />

art taking up the issue of gender<br />

differences. Against the backdrop<br />

of the newly revived patriarchy, the<br />

‘new woman’ is first and foremost<br />

imagined as the mother. This<br />

demotion to the role of the mother<br />

was (and still is) not only high on<br />

the agenda of nationalistic ideologists,<br />

it also had a very practical<br />

reason: women had to stay home<br />

during the period of economic transition<br />

for the simple reason that<br />

they were out of work. Household<br />

matters form a subject that runs<br />

like a red thread through many of<br />

the photographs and videos aiming<br />

at politicizing women’s role in the<br />

private sphere. Some of the works<br />

displayed in this section are about<br />

the crossing of gender borders and<br />

lesbian identity — issues which in<br />

the Eastern European art context<br />

were not tackled until the 1990s.<br />

12_FEMInA:<br />

IdEntIt y, spECtAClE,<br />

MAsquErAdE<br />

In portraits and self-portraits<br />

made after 1989, women artists<br />

CloACkrooM<br />

MAIn hAll<br />

examine female sexuality and<br />

subjectivity. Their approach to<br />

the female body is very different<br />

from that of their colleagues from<br />

the 1970s and 80s, since they are<br />

less interested in the ‘ideal’ body<br />

than in the creatureliness of the<br />

body, its exposedness to decay,<br />

aging and illness. Both in the<br />

self-portraits and in the portraits<br />

of female protagonists, woman’s<br />

‘real’ identity is metaphorically<br />

staged as spectacle and masquerade.<br />

Other works — by male as<br />

well as female artists — rewrite<br />

art history from a feminist<br />

point of view. In many countries<br />

women artists produce works<br />

dealing with female genealogies,<br />

e.g. relationships between mothers<br />

and daughters or between<br />

sisters. Family histories are thus<br />

told along a matrilineal axis.<br />

13_nAtIonAlIsM<br />

And CrItIquE<br />

The foundation of the post-communist<br />

states was preceded by<br />

strong nationalistic movements.<br />

Nationalist ideology was used<br />

as the perfect antidote against<br />

communist ideology. The works<br />

displayed in this section lay bare<br />

nationalism’s fundamentalist and<br />

racist substratum, its masculanism<br />

and its sexism, especially as<br />

these manifested themselves in<br />

the post-Yugoslavian countries<br />

that were involved in the ethnic<br />

wars. Yet even in those countries<br />

pArt III_<br />

_post-CoMMunIst<br />

GEndErsCApEs<br />

that kept out of the wars, nationalist<br />

democracy wears a male<br />

face, since there are practically<br />

no female politicians holding any<br />

of the higher political offices, let<br />

alone the presidential one. Posters<br />

commissioned by political<br />

parties indicate that the female<br />

allegory, which from the mid-<br />

19th century onward embodied<br />

the male ideals of the national<br />

state (e.g. in national monuments),<br />

has gained new currency<br />

after 1989.<br />

14_ConVEntIon<br />

And trAnsGrEssIon<br />

The new socio-political situation<br />

not only called for the invention<br />

of the ‘new woman’ — the<br />

concept of maleness also had to be<br />

revised. Thus, the ‘re-feminization’<br />

and domestication of women<br />

was paralleled by an aggressive<br />

re-masculinization of the public<br />

discourse. Yet most of the works<br />

shown in this section are not<br />

concerned with men’s public roles.<br />

The focus is rather on the private<br />

sphere, with male sexuality being<br />

discussed both from a hetero- and<br />

a homosexual perspective. Some<br />

of the artists subvert the heterosexual<br />

matrix that had remained<br />

unchallenged throughout the<br />

entire era of communism and turn<br />

to the public display of their crossgender<br />

and queer identities. Today,<br />

the term ‘queer’ is used both in<br />

a sexual and a political sense.<br />

15_CApItAl<br />

And GEndEr<br />

10_ 11_ 12_ 13_<br />

14_ 15_ 16_ 17_ 18_<br />

To what extent has women’s<br />

condition changed under the new<br />

democratic regimes? This section<br />

comprises works that deal with<br />

the connections between gender<br />

and capital. In the course of the<br />

social transformations sweeping<br />

over Eastern Europe, the issue of<br />

a new, post-communist femininity<br />

was introduced into the public<br />

debate. While there is a noticeable<br />

tendency to glorify women as<br />

guardians of hearth and home,<br />

the period of perestroika also saw<br />

the emergence of another female<br />

gender role, which, imported<br />

along with democracy, is diametrically<br />

opposed to that of the<br />

mother and housewife: the whore.<br />

The artists presented in this part<br />

of the exhibition are all critically<br />

concerned with issues like sex<br />

work, slave-trade and pornography.<br />

Other works deal with<br />

unemployment and the social<br />

misery rife among women.<br />

9_Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe (Russia), Monroe, 1996, c-print, col. XL Gallery, Moscow © Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe<br />

10_Imre Gábor (Hungary), She Has Been My Wife Since 1992 (To Love, to Fuck & to Die), 2002, photograph, courtesy of the artist © Imre Gábor<br />

11_Elżbieta Jabłońska (Poland), Super Mother, 2002, photograph, courtesy of the artist © Elżbieta Jabłońska<br />

12_Rovena Agolli (Albania), In All My Dreams, It Never Is Quite as It Seems, 2002, digital print, courtesy of the artist © Rovena Agolli<br />

13_Alla Georgeva (Bułgaria), Alla’s Secret. Collection 2000–I, 2000–II, 2000–III, 2000, ink jet prints on paper, aluminium, courtesy of the artist © Alla Georgeva<br />

14_Kriszta Nagy (Hungary), 200.000 Ft, I–VI, 1997, digital print, Collection of Zsolt Somlói and Spengler Katalin, Budapest © Kriszta Nagy<br />

15_Petra Varl (Slovenia), Zvezda and Odeon, 2010, wall painting, courtesy of the artist © Petra Varl<br />

16_Eva Filová (Slovakia), Without Difference, 2001, installation, milk tetra pack, courtesy of the artist © Tomáš Błoński<br />

17_Veronika Bromová (Czech Republic), Girls Too, 1994, digital altered color duratrans in light box, courtesy of the artist © Veronika Bromová<br />

18_Tanja Ostojić (Serbia), Looking for a Husband with EU paszport, 2000–2005, participatory web project, combined media installation, photograph, book, video CrossingOver (in collaboration with Klemens G.), 7’, courtesy of the artist © Tanja Ostojić<br />

_Post-Communist <strong>Gender</strong>scapes<br />

_ 5

Nazwa rozdziału<br />

6_<br />

_ E M o t I o n A l A n d F A M I l y l I F E I n E A s t E r n - b l o C C I n E M A<br />

_EMotIonAl And FAMIly lIFE<br />

In EAstErn-bloC CInEMA<br />

<strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Check</strong> — the first film-related thing<br />

that comes to mind when one thinks of<br />

gender checking may be the popular crossdressing<br />

comedies that play with body and<br />

gender visibility in cinema (and in society).<br />

Think of Wojciech Pokora disguising<br />

himself as a housemaid in Stanisław<br />

Bareja’s Man — Woman Wanted (1973) or<br />

Eugeniusz Bodo imitating May West in<br />

Leon Trystan’s Neighbours (1937). There is,<br />

of course, a second bottom to those funny<br />

scenes (and perhaps a third one too). The<br />

comedy role of Stanisław/Marysia, played<br />

by Pokora, became a pretext for tongue-incheek<br />

qui pro quos and light homosexual<br />

allusions (in Polish culture, homosexual<br />

themes usually appear under a pretext<br />

and under disguise). At the same time, the<br />

problematic issue of gender meets here<br />

the no less problematic issue of social<br />

class: a husband-come-housemaid is<br />

more useful at home than a husband-art<br />

historian, but the domestic help in the<br />

supposedly emancipated socialistic society<br />

_A review of feature films accompanying<br />

the exhibition <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Check</strong>. Femininity and<br />

Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe<br />

Zachęta, 20 March – 13 June 2010<br />

_18 March_Adventure in Marienstadt<br />

[Przygoda na Mariensztacie], dir. Leonard<br />

Buczkowski, Poland, 1954, 93’ (introduction<br />

by Ewa Toniak, PhD). A mix of popular<br />

romantic comedy with the requirements<br />

of socialist realism. A (not very heated) love<br />

affair serves here above all to promote the<br />

idea of women’s (and men’s) — bricklaying<br />

— work and the beauty of Warsaw (openly)<br />

and the Party (indirectly). As well as youth,<br />

commitment and soc-version emancipation,<br />

as in the (pseudo)folk song: ‘The<br />

machines are riding / Girls on them / And<br />

each as a boy… . Because a girl — is people!’.<br />

_25 March_Daisies [Sedmikrasky], dir.<br />

Věra Chytilová, Czechoslovakia, 1966, 74’<br />

(introduction by Paulina Kwiatkowska).<br />

A hilariously told, anarchic story about two<br />

pretty girls that, craving for demoralisation,<br />

play — on their own terms — with<br />

older and younger men. Described as<br />

a ‘philosophical documentary in the form<br />

of a farce’, the film is one of the most<br />

interesting achievements of the Czech<br />

New Wave.<br />

_1 April_Innocence Unprotected [Nevinost<br />

bez zastite], dir. Dušan Makavejev,<br />

Yugoslavia, 1968, compilation film, 75’<br />

Dušan Makavejev is probably the former<br />

Yugoslavia’s most interesting filmmaker.<br />

After Innocence Unprotected, received as<br />

a provocation, he had to emigrate. The<br />

film is based on a 1941 movie of the<br />

same title, the first Serbian sound film, by<br />

Dragojlub Aleksic, a famous acrobat and<br />

strongman. The film was banned by the<br />

Nazi censors and classified as pro-Nazi<br />

propaganda later on. Makavejev montaged<br />

a popular story about a male hero with<br />

WWII-era documentary footage (some of<br />

has to be a woman. Bodo, in turn, imitated<br />

an American actress whose curvaceous<br />

torso lent the name to WWII-era aircrew<br />

life preserver jackets — only the very Mae<br />

West image was an imitation in itself,<br />

a representation of femininity, super-femininity<br />

embodied. Thus filmic narratives<br />

and the gestures of film characters reflect<br />

social praxes, but also reproduce and copy<br />

them, disseminating them in effect. At the<br />

same time, demonstration is sometimes<br />

destruction and an ostentatious supervisibility<br />

of femininity (masculinity)<br />

exposes them as nothing but constructs.<br />

Belief in the causal power of images was<br />

something that guided socialist-realist<br />

artists — the essence was supposed to<br />

become more marble-like and real bodies<br />

were to model themselves upon the<br />

designed ones, becoming a bit less sexually<br />

different, a bit stronger, channelling<br />

their sexual energy in work. The costume<br />

of a worker or peasant (the latter less<br />

preferred, though), or at least a member<br />

of the Komsomol, covered all that could<br />

be the non-political body (→Adventure in<br />

Marienstadt). Post-socialist realist cinema<br />

— from Warsaw to Moscow and from<br />

it manually coloured by him) — Nazi and<br />

Serbian collaborationist propaganda films,<br />

German military newsreels, but also the<br />

Alexandrov Circus, Aleksic’s performances<br />

and interviews with the members of the<br />

original cast and crew. The compilation<br />

becomes an accusation of both communism<br />

and fascism, but also a reflection on<br />

the process of the creation of a collectiveimagination<br />

hero and on the Yugoslav<br />

culture in its official and popular versions.<br />

The film won the FIPRESCI Award and<br />

the Silver Bear Extraordinary Prize of the<br />

Jury at the 18th Berlin International Film<br />

Festival in 1968.<br />

_8 April_How to Be Loved [Jak być kochaną],<br />

dir. Wojciech Jerzy Has, Poland, 1963, 97’<br />

A psychological drama told from the<br />

viewpoint of a woman who during the<br />

war sacrificed everything to save the<br />

man she loved. A polemical version of<br />

history — heroic, but also taking place in<br />

the private sphere — in which the woman<br />

are strong active and the men weak and<br />

passive. The past is shown through the<br />

retrospections of the main character,<br />

Felicja, now a well-known actress, popular<br />

thanks to her role in a radio soap opera,<br />

through which she fulfils (and promotes)<br />

the ideal of harmonious family life. The<br />

film won the Golden Gate Award for Best<br />

Actress (Barbara Krafftówna), Best Picture<br />

(Wojciech Has) and Best Screenplay<br />

(Kazimierz Brandys) at the San Francisco<br />

International Film Festival in 1963.<br />

_15 April_Ecce Homo Homolka, dir. Jaroslav<br />

Papoušek, Czechoslovakia, 1969, 79’<br />

The film was the full-length debut of the<br />

screenwriter of Forman’s and Passer’s New<br />

Wave movies. In the opening sequence,<br />

a Prague taxi driver and his family on<br />

a weekend outing in the woods run away<br />

frightened upon hearing calls for help.<br />

Then it only gets worse — the plot moves<br />

entirely to a family apartment, in which<br />

the Baltic to the Black Sea (in all those<br />

places where the censors left artists an at<br />

least narrow margin of freedom) — will<br />

unanimously steer towards the private<br />

sphere: intimate emotions and family<br />

issues. The bloc’s film dramas became<br />

either repeatable and bland or did not<br />

show happy families.<br />

The family (though there were exceptions)<br />

was a field where social tensions<br />

could be safely explored. In a way, it<br />

was also the only one, because critically<br />

reviewing the public sphere and openly<br />

polemicising with the official political<br />

rhetoric was not allowed. Nonetheless,<br />

it is in the family and the sphere of<br />

sexuality (→Innocence Unprotected) that<br />

the various aspects of human existence<br />

are all present and the individual meets<br />

the collective: the work (and pay) of<br />

men and women, their consumer and<br />

emotional needs (and their (un)fulfilment)<br />

(→Adoption; A Woman Alone), relationships<br />

between parents and children, spouses<br />

or partners, the politics of the body and<br />

fertility (→4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days),<br />

but also politics in the common sense of<br />

the word, invading privacy in the shape<br />

three generations of men and women<br />

torment each other. All that because the<br />

TV set has gone wrong. The tragicomic<br />

story, a witty portrait of a certain form of<br />

family life, is the first part a trilogy about<br />

the Homolka family.<br />

_22 April_Adoption [Örökbefogadás],<br />

dir. Márta Mészáros, Hungary, 1975, 89’<br />

An unhurried, detail-focused, nuanced<br />

story about Kata, a lonely widow in her 40s<br />

living in the countryside. She still dreams<br />

of having a child, but her married lover<br />

doesn’t like the idea. The situation changes<br />

when Anna, runaway from a nearby assisted<br />

living facility, finds her way to Kata’s<br />

house. The film won the Golden Bear at<br />

the 1975 Berlin International Film Festival.<br />

_29 April_Inner Life [Życie wewnętrzne],<br />

dir. Marek Koterski, Poland, 1986, 86’<br />

Of all the neurotic protagonists of Marek<br />

Koterski’s movies, this one is surely one<br />

of the most interesting. The plot is set in<br />

the claustrophobic space of an apartment<br />

block, its narrow ‘communication passages’<br />

— the corridors and the elevator — and the<br />

main character’s mind. An image of the<br />

disintegration of both public and private<br />

bonds and of emotionality reduced to two<br />

basic instincts: aggression (dominant) and<br />

sex (realised only in the sphere of fantasies<br />

and fear of the ‘night stalker’). The film<br />

won an award for Best Director at the 1987<br />

Polish Film Festival in Gdynia.<br />

_6 May_A Woman Alone [Kobieta samotna],<br />

dir. Agnieszka Holland, Poland, 1981<br />

(premiere 1987), 92’ The main character,<br />

a Wrocław mail carrier (Maria Chwalibóg),<br />

is a member of neither the Party nor<br />

Solidarity and receives no support from<br />

either her family or friends. She raises her<br />

8-year-old son alone. One day she meets<br />

a young disability pensioner (Bogusław<br />

Linda), limping after a coalmine accident.<br />

Both would like to see a radical change in<br />

of war or institutional violence (→How<br />

to Be Loved; Grbavica; Another Way). What<br />

could be shown was determined by the<br />

level of censorship — a ‘thaw’ in Soviet<br />

politics and cinema in the 1950s spawned<br />

protagonists who sometimes gave<br />

precedence to the lyrical (e.g. enamoured)<br />

self over one’s social duties; the perestroika,<br />

in turn, brought a foamy wave<br />

of chernukha [pessimistic neo-naturalism]<br />

art (→Little Vera), under the pressure of<br />

which no stable values held ground.<br />

Cinema accompanied those changes, but<br />

it also helps us to examine them more<br />

closely. When we see working women,<br />

we also see a lack of respect for their<br />

work, low pay and lack of institutional<br />

support (→A Woman Alone). When we see<br />

frustration of men at home, we see their<br />

inability to fulfil themselves in the closed<br />

public field (Jak być kochaną). All that is<br />

left to them are reminiscences of a past<br />

war and their heroic role in it (→Innocence<br />

Unprotected) — sometimes leading to<br />

a new war (→Grbavica).<br />

Showing quickly rechannelled youth<br />

discontent (e.g., paradoxically, Daisies,<br />

1966) or actually young people’s inability<br />

their lives. Holland paints an insightful —<br />

and painful — picture of the life of people<br />

outside the focal point of historic events,<br />

refusing to fit into the simple us-versusthem<br />

divisions, doomed to live a gloomy<br />

existence. The film’s message was so<br />

pessimistic that, despite being censored,<br />

it was shelved for six years. A Woman<br />

Alone won the Special Prize of the Jury for<br />

Agnieszka Holland and Best Actor awards<br />

for the lead role performers at the 1988<br />

Polish Film Festival in Gdynia.<br />

_13 May_Little Vera [Malenkaya Vera],<br />

dir. Vasili Pichul, USSR, 1988, 128’<br />

One of the more interesting, best known<br />

— and most popular — films of the<br />

chernukha, a pessimistic, neo-naturalistic<br />

trend describing the Soviet society of the<br />

perestroika era. Teenage Vera lives in a port<br />

town on the Black Sea. A relationship with<br />

Sergey, a boy met on the beach, gives her<br />

some relief from the family conflicts at<br />

home. Her parents, however, don’t approve<br />

of the boy, who irritates them with his<br />

refusal to be like ‘everyone else’. The film<br />

won numerous awards, including the<br />

FIPRESCI Prize at the 1988 Venice Film<br />

Festival, the European Film Award for Best<br />

Screenwriter in 1989, and the Special Jury<br />

Prize at the 1988 Montreal World Film<br />

Festival.<br />

_20 May_Another Way [Egymasra nezve], dir.<br />

Karoly Makk, Hungary, 1982, 102’<br />

(introduction: Bartosz Żurawiecki). The film<br />

is set during the ‘normalisation’ period<br />

following the 1956 uprising in Hungary and<br />

depicts the three protagonists in confrontation<br />

with history — and their own feelings.<br />

Eva falls in love with the married woman<br />

Livia, who, though not without misgivings,<br />

eventually responds to her love. A lyrical<br />

study of their romance is confronted with<br />

the brutality of public life and language.<br />

A forbidden love is inextricably linked<br />

here to political proscriptions and the<br />

_FIlM<br />

proGrAMME<br />

to rebel and a destruction of the domestic<br />

and family sphere (→Inner Life; Ecce Homo<br />

Homolka; Little Vera), filmmakers were<br />

actually showing a society in a state of<br />

implosion. All attempts of transgression<br />

and non-normative gestures were sternly<br />

punished in it (→Another Way) and the<br />

atrophy of social bonds (→4 Months,<br />

3 Weeks and 2 Days) is reflected in the<br />

disintegration of the stable self (→Inner<br />

Life; A Woman Alone).<br />

When a social explosion took place,<br />

cinema did not explode at all. It opened<br />

itself towards new subjects and new<br />

types of protagonists, but remaining<br />

a step behind the transitions, not so<br />

much redefining the space of the debate<br />

as capturing, like a radar, the changes<br />

taking place in both the public and<br />

private spheres. It has been diagnosing<br />

rather than designing, acting like<br />

a scalpel rather than like a hammer. This<br />

is because a fundamental transformation<br />

requires a radical language on the part<br />

of the medium itself and that is present<br />

more often in the other visual arts.<br />

Iwona Kurz<br />

transgression of social conventions — to<br />

actual borders. The movie features superb<br />

performances by two Polish actors,<br />

Grażyna Szapołowska (Livia) and Jadwiga<br />

Jankowska-Cieślak (Eva, Best Actress at<br />

1982 Cannes Film Festival).<br />

_27 May_4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days [4 luni,<br />

3 săptămâni şi 2 zile], dir. Cristian Mungiu,<br />

Romania–Belgium, 2007, 113’<br />

The plot is set in Romania in the late<br />

1980s and tells the story of Gabita who<br />

decides to have a late abortion, in which<br />

she is being helped by her friend, Otilia. An<br />

illegal abortion becomes here a symbol of<br />

living in a society where everyone who has<br />

any power uses it against others, where<br />

social bonds are a matter of commercial<br />

exchange and emotions a matter of<br />

contract. The film won numerous awards,<br />

including the Golden Palm in Cannes and<br />

the European Film Award in 2007 for Best<br />

Film and Best Director.<br />

_10 June_Grbavica [Esmas Geheimnis<br />

— Grbavica], dir. Jasmila Žbanić, Austria–<br />

Croatia–Germany–Bosnia and Herzegovina,<br />

2006, 90’ (introduction: Bożena Umińska-<br />

-Keff). One of the first films breaking away<br />

with Yugoslav-style self-Balkanisation<br />

à la Kusturica. A lone mother is raising<br />

her 12-year-old daughter, Sara, in the<br />

Sarajevo neighbourhood of Grbavica. The<br />

girl believes her father was a Bosnian hero<br />

whereas in truth she was born as a result<br />

of a rape committed by a Serbian soldier.<br />

The film won the Golden Bear at the 2006<br />

Berlin International Film Festival<br />

Thursdays at 16:00 screenings of films by<br />

Marina Gržinić and Aina Šmid, multimedia<br />

room, entrance through the exhibition<br />

Three Sisters [Tri sestre], video, 1992, 28’<br />

Bilocation [Bilokacija], video, 1990, 12’06’’<br />

Luna 10, video, 1994, 10’35’’<br />

edited by Iwona Kurz

_ l E C t u r E s , M E E t I n G s , d I s C u s s I o n s<br />

_ A r E V I E W o F d o C u M E n t A r y F I l M s<br />

_ G u I d E d t o u r s<br />

_ W o r k s h o p s F o r C h I l d r E n<br />

_lECturEs, MEEtInGs, dIsCussIons<br />

_EduCAtIonAl<br />

proGrAMME<br />

• 20 March (Saturday), 12:00 Meeting with Wojciech Fangor about his 1950 painting Figures, with the participation of Agnieszka Morawińska, PhD (moderator), Ewa Franus,<br />

Katarzyna Murawska-Muthesius, PhD, Ewa Toniak, PhD; meeting will be translated live into English; multimedia room, admission free<br />

• 21 March (Sunday), 12:15 Guided tour by curator Bojana Pejić (in English); main lobby, admission included in ticket price<br />

• 28 March (Sunday), start 11.30 Zachęta goes Wiki; multimedia room, admission free<br />

11.30 – 12.30 Free Culture — Free Art? Discussion panel with the participation of Krzysztof Siewicz, attorney at law, devoted to Creative Commons licences for works of art,<br />

Małgorzata Bogdańska-Krzyżanek (moderator)<br />

12.45 – 14.15 Workshop: creating Wikipedia entries about works in the Zachęta National Gallery of Art collection — led by Masti (Marek Stelmasik) & Przykuta<br />

(Sebastian Skolik)<br />

14.30 –15.30 Guided exhibition tour<br />

15.45 – 17.15 Workshop: Wikipedia Women, Come On! — led by Claudia Snochowska-Gonzales<br />