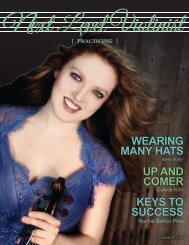

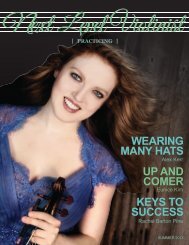

Next Level Bassist Practicing Edition

Articles by David Allen Moore and Rufus Reid, interviews with Jonathan Borden (Buffalo Philharmonic), Dan Carson (Principal, Alabama Symphony), and Alex Jacobsen (National Symphony). Free sheet music by Ranaan Meyer, gear reviews, and more!

Articles by David Allen Moore and Rufus Reid, interviews with Jonathan Borden (Buffalo Philharmonic), Dan Carson (Principal, Alabama Symphony), and Alex Jacobsen (National Symphony). Free sheet music by Ranaan Meyer, gear reviews, and more!

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The<br />

ext evel<br />

N L<br />

The Practice Issue<br />

Rufus Reid<br />

shares valuable insight into how<br />

to get the most out of<br />

your practice sessions.<br />

Fall 2013<br />

assist<br />

David Allen Moore<br />

gives you a cohesive and<br />

easy plan to follow in order<br />

to gain the most effective<br />

results from practice.

2 • <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist<br />

ext evel<br />

N L<br />

Letter from the Publisher<br />

Practice covers a surprisingly large amount of our lives as musicians. What do I mean by that? Well,<br />

whether you’re in the practice room, or walking around thinking about how to get better, you are still<br />

practicing. Practice can be done with the instrument, away from the instrument, and it has an on and<br />

off switch (even though sometimes, you have to force yourself to press it!) As a bass player, you have<br />

time to excel on the instrument, trying things out, experimenting to decide if an idea works or not. You<br />

may also be implementing a design that you already know works. You will ultimately spend thousands<br />

of hours practicing intonation, rhythm, new music, improvisation, feel, awareness — the sky is the limit.<br />

Away from the instrument, you should find yourself thinking about practice.<br />

In this edition on practicing, you will find a variety of approaches to very specific aspects of double bass<br />

playing. The information contained may run against your own knowledge, or things you have heard in<br />

your studies, but every word in these pages is excellent and worthwhile. Your challenge is to test these<br />

approaches and see how they can help you improve.<br />

I found my own way of practicing through years of playing the bass, collaboration, study, listening to<br />

trusted mentors, listening to non-musicians, and our old friends, trial and error. Like everything else on<br />

the bass, it falls to you as the individual to put the pieces together. You have to figure out what works for<br />

you! Personally, I’ve always thought of myself as something of a doctor, diagnosing where problems lie<br />

and deciding how to improve the situation. What medicine do I need to make the thing I’m working on<br />

better?<br />

Finally, a word about technology. There are a thousand supplies at your disposal as a musician today.<br />

The metronome, video, recording on your computer or phone, the list goes on and on….These devices<br />

can offer perspective. Outside perspectives are so important for feedback — this isn’t just about playing<br />

for others, it’s about using the “tools of self-reliance” to aid in your growth. I’m going<br />

to go out on a limb here and say if you aren’t using, or learning to use, those<br />

tools in your practice, you’re probably not maximizing the time you’re spending!<br />

No matter what you get out of this particular edition of The <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> <strong>Bassist</strong>, remember<br />

to take an individual approach to your own practice, and use it to better<br />

yourself at all times.<br />

It’s my job here to restate that this is supplemental information, like a library book<br />

or encyclopedia. This is not a substitute for real life experience, but if it can help<br />

you find more solutions for practicing, as you progress as a double bass player<br />

into your career, then I’ll see you on the <strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong>!<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

Publisher<br />

assist

Sta<br />

Publisher • Founder<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

Editor • Sales<br />

Brent Edmondson<br />

Copyeditor • Layout<br />

Jessica Arnold<br />

johnson<br />

string instrument<br />

VIOLINS, VIOLAS, CELLOS, BASSES & GUITARS<br />

www.johnsonstring.com<br />

THE BASS SHOP<br />

26 Fox Road<br />

Waltham, MA 02451<br />

800-359-9351<br />

<br />

susanwilsonphoto.com<br />

Contents<br />

Feature Stories<br />

To Practice or Not to Practice? 9<br />

By Rufus Reid<br />

Make Practice Perfect 20<br />

By David Allen Moore<br />

Exclusive Interviews<br />

Getting There 3<br />

With Jonathan Borden,<br />

Dan Carson, and Alex Jacobsen<br />

Additional Features<br />

Transition and Stronger 15, 18<br />

Music by Ranaan Meyer<br />

<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong> <strong>Bassist</strong> Review: 24<br />

DPA d:vote 4099B<br />

By Ranaan Meyer<br />

<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist • 3

Getting<br />

There<br />

An NLB<br />

Exclusive<br />

Interview<br />

Feature!<br />

Auditions can make or break your career.<br />

From practice routine to mindset and everywhere in between, some of the industry’s<br />

brightest rising stars give their most valuable advice and discuss the strategies<br />

they used before stepping in front of the screen.<br />

NLB: How do you decide which auditions to take? Do you<br />

have a preference of named-chair vs. section auditions?<br />

Dan Carson: I had never taken an audition before, and my<br />

teachers kept telling me that I should “get one out of the way”<br />

before my junior year. I didn’t end up doing one last year,<br />

but I knew that auditioning for IU orchestra seating and<br />

summer festivals weren’t the same experience as a professional<br />

audition. I needed to go out and get exposure to the<br />

real world. It wasn’t necessarily that Alabama was holding<br />

a Principal audition, but it was an orchestra at a level I was<br />

comfortable with approaching so I decided to take it on.<br />

Alex Jacobsen: Since I was in school, distance was a big priority.<br />

I didn’t want to drop a lot of money on something<br />

I wasn’t very condent in while I was still developing the<br />

“package,” my way of presenting myself at auditions. Another<br />

big consideration was the size of the list, and how that<br />

t into what I was doing at the time. I don’t want to destroy<br />

myself for nothing! As a student, I was into any audition I<br />

could get my hands on. I didn’t say things like, “I can’t see<br />

myself in this orchestra.” I just wanted to throw myself into<br />

something. Eventually, I would like to perhaps play principal<br />

in an orchestra because I enjoy sitting in the front and<br />

making decisions. Ultimately, a principal still needs to play<br />

with the section, so the skill sets have a lot of crossover, and<br />

I’m excited to play in any position.<br />

NLB: What sort of prep work did you do for this audition?<br />

Was it dierent from other auditions you’ve taken? How was<br />

it dierent from your routine when not preparing for auditions?<br />

Jonathan Borden: I got the list about ve weeks before<br />

hand, and used a system of A, B, and C-lists based on how<br />

well I knew the excerpts. I focused on the least familiar excerpts:<br />

my “C”-list rst, and tried to build all the repertoire<br />

towards an “A”-list level. I wanted to get all of my decisions<br />

about ngerings and bowings – as well as musical decisions<br />

– to a good level as early as possible. About two weeks before<br />

the audition process, I started trying to really practice the<br />

performance element; I played for a lot of people, gave mock<br />

auditions at school, pulling people into my practice room all<br />

the time to get feedback. I had only taken the Boston Symphony<br />

audition previously and the approach was a little different.<br />

I felt more comfortable with the whole process and<br />

was able to rene the approach – I specically knew I needed<br />

to develop the performance aspect of the audition and was<br />

able to focus on how I would play when I got on stage. I<br />

spent some time on keeping cool in the moment.<br />

AJ: In my previous auditions, there was a lot of variety of<br />

approach. I would divide my list into three sections and basically<br />

do a lot of non-musical planning of my preparation.<br />

In this audition, I decided to do everything I could to make<br />

each excerpt sound as good as possible right away. In the<br />

past, I’ve allowed intonation or tone issues to go by for a day<br />

or a week, but I wanted to eliminate that tendency. A month<br />

out, I wanted to make sure I captured the essence of each<br />

excerpt so I would be used to that at the actual audition.<br />

DC: I nd that my practice techniques are perhaps a bit lacking<br />

in variety, but about 85 percent of my time is spent working<br />

things up with the metronome. You have to really take<br />

a passage down to the fastest tempo you can play perfectly,<br />

which for me is usually quite slow. I start speeding up and as<br />

soon as it doesn’t feel perfect anymore, back down from that<br />

tempo and work out the issues. It’s very methodical, and I<br />

try to be a very logical thinker. Most of the practicing I do<br />

seems very black-and-white. Recording myself was another

great resource. Sometimes it’s hard, and I didn’t always want<br />

to listen to myself, but it’s really for the best.<br />

NLB: How do you deal with nerves the day of?<br />

JB: At my Boston audition, the nerves really hit me on stage.<br />

I tried playing for a variety of people leading up to that audition,<br />

having read that you should do that. I even played a<br />

few times for my studio behind a screen. ey would try to<br />

mess me up by throwing a chair or something meant to break<br />

my focus! All that preparation was great, but when I got on<br />

stage, I still had a nervous reaction. I don’t think I played as<br />

well as I could have because of the nerves. I learned so much<br />

by just taking that audition. People will say that the best way<br />

to get rid of nerves is to just play for people, but the best way<br />

is really just to play a lot of auditions. e experience put me<br />

on the right track. First, I needed an audition to understand<br />

what it would be like in the moment, and then I developed<br />

several breathing techniques. e two books by Don Greene<br />

(Performance Success and Audition Success) and e Inner<br />

Game of Tennis all helped me understand the mental state I<br />

needed to be in to have success and play well. Instead of just<br />

playing for people, I went through a structured mental warmup<br />

routine before playing. I was getting in the right state<br />

of mind rst. When I got to the audition, I had this routine<br />

that I could fall back on to feel comfortable.<br />

I think that it’s a worthwhile goal to learn how to<br />

master your nerves and be in control of your body. I learned<br />

a lot from it.<br />

DC: What I’ve been telling people is that I was really taking<br />

this audition for practice in the rst place. I wanted to<br />

experience the type of nervous reactions that people always<br />

talk about when discussing auditions. In the nals, my bow<br />

was just bouncing everywhere and my right hand could not<br />

stay still! It was frustrating but it was also exactly what I was<br />

trying to discover by taking an audition. I went in not expecting<br />

anything, and I would say that is almost the best way<br />

to handle nerves. e approach of being condent in what<br />

I have to oer and trying to enjoy myself playing because I<br />

love music is better than worrying about playing a certain<br />

excerpt better than someone else. If you are trying to make<br />

some great music, you won’t be a slave to nerves.<br />

NLB: Now that you’ve won your job, what’s next? How often<br />

and for what are you practicing now?<br />

DC: I was initially inclined to take a break from auditioning,<br />

but a lot of people in my life have encouraged me to continue<br />

auditioning right now – especially for other principal positions.<br />

I am in good shape, and it would be great to nd some<br />

momentum from this success into another. I don’t think that<br />

section positions are o-limits by any means, but one of the<br />

reasons I wasn’t hesitant to take the position in Alabama is<br />

because I’ve been told that winning a principal job with experience<br />

as a principal is easier than simply winning that job<br />

outright. Detroit and Vancouver are a bit too soon on the<br />

horizon, but soon enough I think I will be back out there on<br />

the scene.<br />

AJ: At this point, I have a lot of the orchestra parts for next<br />

season and I’m going to be practicing them quite a bit. I<br />

have a probationary period ahead of me and I want to be<br />

completely on top of my game, not slowing anyone down. I<br />

think the main focus of my practice is making sure I know<br />

what I have to do to play well in a very nice orchestra. I felt<br />

like I really stepped up my game for the audition, playing at<br />

a higher level than I normally play. It’s vital that I keep my<br />

game at that level from now on, making it the new normal.<br />

It’s always good to keep Bach on the plate too – it’s really<br />

pretty scales and a great way to keep everything sharp.<br />

JB: I’ve spent so much time in school working on excerpts<br />

– I really tunnel-visioned the whole audition process. I want<br />

to work on some more solo repertoire. I’m giving a senior<br />

recital next year at Juilliard, and I’ll be working on some<br />

Bach, sonatas, and other things. I’d love to develop my solo<br />

playing to the same level as my excerpt playing. Juilliard was<br />

great at negotiating a way for me to nish my degree and<br />

start playing with Bualo in January. I’m really glad to be<br />

entering my career with a bachelor’s degree. Many people<br />

have master’s degrees and a degree is a must have these days.<br />

NLB: What was the one moment you had studying bass that<br />

changed everything for you? Was there a word from a teacher,<br />

or a fellow student, or a specic turning point?<br />

AJ: ere was one point in high school when I wasn’t really<br />

practicing very much. I showed up to a lesson, and my<br />

teacher asked if I had worked on the rep he gave me. Aer<br />

I played a bit, he came over to my bass and just laughed. In<br />

between the feet of my bridge was a spiderweb and the spider<br />

was just hanging out there. It could not have been more<br />

obvious I hadn’t touched my bass all week, and at that point<br />

I felt really embarrassed. My teacher called my mom and<br />

told her I could have been making so much more progress<br />

if I worked at it. It was an existential “oh crap” moment because<br />

I identied myself as a bass player. I realized I could<br />

either coast or actually try to apply myself. It wasn’t just that<br />

moment, but that was a very vivid memory to spur me on to<br />

where I am today.<br />

JB: I was on the fence for a while. I didn’t really choose<br />

to be serious until the summer aer my junior year in high<br />

school. I was at Bowdoin and I got really inspired by Kurt<br />

Muroki – watching him play and seeing what he was capable<br />

(Continued on Page 6)

of really pushed me to try a lot more. It was a combination<br />

of things, but I remember playing Beethoven 9 with him and<br />

it was awe-inspiring to experience that incredible piece in the<br />

orchestra. Aer, I came to Juilliard pre-college and it gave me<br />

a glimpse into conservatory life. When it came to decision<br />

time, I had applied to conservatories and universities. I was<br />

undecided but all those experiences made me feel certain that<br />

I should go to Juilliard and pursue this full time.<br />

NLB: What advice would you give to someone who is in the<br />

beginning or middle of their audition career? Was there a<br />

hopeful thought that kept you going, or something driving<br />

you forward?<br />

DC: I would have to say that having a positive and carefree<br />

attitude will come through in your playing. My mom always<br />

tells me, “row your hat in the ring.” ere were all these<br />

times when I wanted to bail on opportunities like festival auditions<br />

because I didn’t think I was prepared enough. e<br />

only way you know you’re not going to succeed is to not try.<br />

It’s worked out every time for me. You may not know what’s<br />

going to happen, but if you bring your condence and positivity<br />

to everything you do, you have a great chance.<br />

AJ: I heard this quote a long time ago that when you rst<br />

start playing an instrument, the things that come out don’t<br />

match what you have in your mind. You have tastes and likes<br />

or appreciate what a master player is doing, but hearing yourself,<br />

you know it’s not the most amazing thing anyone’s ever<br />

done. It takes years and years to get to that level – there are<br />

still a million things I want to x in my own playing, but just<br />

having patience and not freaking out when things aren’t immediately<br />

going your way is a huge part of development and<br />

something I want to remember going forward. You can’t have<br />

success without patience and dedication. Cut yourself some<br />

slack every now and then. You have to push yourself as hard<br />

as you can, but realize that you’re just a human and everyone<br />

has to work for everything they’ll ever get. Also, having fun<br />

with music – I almost forgot! Playing with dierent people,<br />

nding music you like playing – it’s important to nd a way<br />

to express yourself through music. Jamming, playing something<br />

on piano, it’s important to be able to relax while playing<br />

music and focus at other times. I played a lot of jazz in high<br />

school, although I’m not in the same shape I used to be. I play<br />

piano as well. It’s a nice way to visualize music and to sound<br />

things out. Bass is notoriously dicult to play in tune, so if<br />

you’re looking at something for the rst time, it helps to play<br />

it robotically on piano to get it in your ear.<br />

NLB: Do you have any teaching experience? Did that aect<br />

your career? How? Do you plan to teach now?<br />

JB: My teaching experience is more sparse than I would<br />

like. I’ve been working with the Pre-College division for the<br />

last three years; playing in the orchestra, coaching the players,<br />

and teaching some private lessons as well. I hope to get<br />

more experience in the future. It would be excellent to have<br />

a studio in the future. It would help me learn. One of the<br />

best ways to develop your playing is to explain those things to<br />

someone else.<br />

AJ: I’ve taught a few private lessons here and there, and I also<br />

taught at a camp for 8-14 year-olds that I went to as a little<br />

kid. It was very cool to be on the other side of the fence, conducting<br />

orchestra pieces and trying to communicate to eight<br />

year-olds what I wanted to happen – it was way harder than I<br />

thought it would be! I don’t think teaching has factored into<br />

my orchestral career yet, but I wouldn’t have gone into music<br />

without the great teaching I had, and I would very much like<br />

to pass the baton to the younger generation going forward.<br />

at’s how I learned and how I got so much out of music.<br />

With teaching, you can see a subject from a totally dierent<br />

angle. Watching someone in a lesson struggle with something<br />

I have experienced and overcome, you have to come up with<br />

the answers for them all over again. I really think you can use<br />

those perspectives to improve your own playing too. It’s like<br />

a recording in that way. If not essential, teaching is extremely<br />

important to musical development.<br />

NLB: Do you have any excerpts or solos for auditions that<br />

you feel extra comfortable with? Anything you want to be on<br />

a list because you’ll nail it?<br />

JB: I’ve always felt very good about my Koussevitzky concerto.<br />

In terms of all the solos you can play for auditions, it’s easy<br />

to negotiate, easy to be expressive on. I nd that the pressure<br />

helps me be extra-expressive, too. It’s perhaps the best choice<br />

available to us. In terms of excerpts, Beethoven 9 letter M<br />

is a fun one. It’s pretty tough, but I know I can play it well<br />

and I can have fun with it on stage. I’ve always liked the rst<br />

movement of Mozart 35. All the excerpts I feel I can groove<br />

to are friendly. Tchaikovsky 4 isn’t too dicult, and it’s fun to<br />

play loud!<br />

DC: I was inclined to say, “No, I don’t feel comfortable with<br />

any of them.” (He laughs.) But I feel that the rst movement<br />

of Brahms 1 at Letter E really caters to some of my strengths.<br />

It is a comfortable loud dynamic and it aords a lot of opportunities<br />

for big vibrato. I’ve been really developing that into<br />

one of my strengths as well. It’s at a moderate tempo so I don’t<br />

feel tense while playing it. Pieces like Mozart 35 are always<br />

risky for tension, even when they’re under my ngers. I’ve<br />

found over the past few years that there are certain excerpts<br />

that have been barriers for me. A couple years ago, it was rehearsal<br />

9 in Ein Heldenleben, but performing it at Aspen this<br />

past summer, I found a magical something about playing it. I<br />

feel like a contender with that one now! Now, I work on Mozart<br />

35 day-in and day-out, and while it’s my current barrier, I

know that I’m going to nd the way to negotiate it.<br />

AJ: Mahler 2 rst page is my favorite excerpt – it’s really,<br />

really loud and then really, really quiet, and very rhythmic –<br />

all these things are my strong suits. I really enjoy being very<br />

intense and, not metronomic, but incredibly insistent. One<br />

thing that Joe Conyers told me leading up to this was that he<br />

tries to make every excerpt his favorite excerpt – don’t have a<br />

nemesis on your list! at was a big part of my preparation.<br />

e committee was going to hear everything on the list and<br />

I needed to be ready for that no matter what.<br />

I constantly freak out about Mozart 35, the rst<br />

movement. It’s really easy to not get that excerpt exactly<br />

right. e fourth movement…Well I’ve worked on it so<br />

much because I used to hate it, so that’s more comfortable<br />

now. But when you look at the rst movement, there are<br />

all these octaves that will sound wrong if they’re not exactly<br />

right, followed by trills in the low register. ese are things I<br />

have to work on a lot to feel comfortable.<br />

NLB: How does an orchestra job t in with your career<br />

goals? Did you always want the job, did you grow to love it,<br />

do you want to use it as a platform for something else?<br />

JB: Getting a job – any job – has always been at the forefront<br />

of my mind. Now that I have that, I’d like to collaborate as<br />

much as possible. Once I’m settled in, I’d love to give more<br />

recitals and participate in more chamber music. It’s hard to<br />

say whatever else is down the road, but I’m open to the possibility!<br />

AJ: I’ve never had a job before so this is the beginning of a<br />

very new phase for me. Right now, I feel like I already know<br />

how to play in orchestra, but i want to build those skills as<br />

much as I can. I would like to play principal at some point<br />

in my life, but I’m sure I could be happy playing in National<br />

for the rest of my life. Well, I’m assuming, because I haven’t<br />

actually played there yet! If the opportunity ever came up, I<br />

wouldn’t turn it down, but all that is still a long way down the<br />

road. I’m focused on what’s immediately ahead.<br />

NLB: Final thoughts?<br />

DC: I’d have to take the Nike slogan: Just Do It. e only<br />

way you know you’re not going to win is by not doing it!<br />

JB: Everything that I’ve done in school has been leading<br />

up to this. All the non-professional auditions have all been<br />

geared towards preparing me for an orchestral audition. I<br />

don’t want to generalize, but it seems that many people want<br />

to put o auditioning until they feel ready. I started preparing<br />

for the Bualo audition when I rst arrived at school!<br />

Get excerpts under your belt, start thinking about the con-<br />

certi and Bach movements that you will need to play in a few<br />

years. Take strategic summer festival auditions that include<br />

repertoire you haven’t seen yet, and plan out your future over<br />

a long period of time. Get your hands on some lists, nd out<br />

what might be asked of you. Take nearby auditions. You<br />

have to get used to doing this. If you feel good with your<br />

playing, the bar isn’t so impossibly high that you shouldn’t<br />

try!<br />

AJ: Patience and enjoying music are two incredibly important<br />

ingredients to a successful music career. I haven’t exactly<br />

started my own career yet, but music is totally awesome<br />

and musicians are blessed to be able to devote their lives to<br />

something so beautiful and wonderful. e audition mentality<br />

is opposed to the fundamental nature of music, which<br />

is about openness and sharing and feelings. at’s more like<br />

real life, where auditions make you worry about out-playing<br />

someone, outrunning the bear. e real test of an audition is<br />

to have technical mastery and a personality. You have to develop<br />

them both – they’re really two sides of the same coin.<br />

Hal Robinson has always told me that he likes to develop<br />

musicality in his playing as early in his approach to a new<br />

piece as possible, because you can’t really accomplish anything<br />

without caring about it.<br />

Raised in Ridgeeld, CT, Jonathan<br />

Borden is entering his nal year of<br />

undergraduate studies at the Juilliard<br />

School studying under Albert Laszlo.<br />

He has appeared with the Tanglewood<br />

Music Center, the Pacic Music<br />

Festival, the Aspen Music Festival<br />

and School, and the Sarasota Music<br />

Festival. He will begin with the Buffalo<br />

Philharmonic in January 2014.<br />

Alex Jacobsen, from Albuquerque,<br />

New Mexico, began studying bass at<br />

age 14 with Mark Tatum. When he<br />

was 18, he was accepted into the Curtis<br />

institute of Music where he studied<br />

with Hal Robinson and Edgar Meyer.<br />

He has attended Brevard Music Center,<br />

Aspen Music Festival and School, and<br />

the Verbier Festival.<br />

Daniel Carson started the bass in his<br />

fourth grade music class and has been<br />

playing for 11 years. He has studied<br />

with numerous teachers, including<br />

Andy Anderson, Jason Heath, Lawrence<br />

Hurst, and, most recently, Bruce<br />

Bransby.<br />

<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist • 7

Welcome<br />

Kurt Muroki<br />

Double Bass<br />

More<br />

Professor Muroki<br />

will join the string<br />

faculty this fall.<br />

than 180 artist-teachers<br />

and scholars comprise an extraordinary<br />

faculty at a world-class conservatory<br />

with the academic resources of a<br />

major research university, all within<br />

one of the most beautiful university<br />

campus settings.<br />

STRING FACULTY<br />

Atar Arad, Viola<br />

Ik–Hwan Bae, Chamber Music, Violin<br />

Joshua Bell, Violin (adjunct)<br />

Sibbi Bernhardsson, Violin, Pacica Quartet<br />

Bruce Bransby, Double Bass<br />

Emilio Colon, Violoncello<br />

Jorja Fleezanis, Violin, Orchestral Studies<br />

Mauricio Fuks, Violin<br />

Simin Ganatra, Violin, Pacica Quartet<br />

Edward Gazouleas, Viola<br />

Grigory Kalinovsky, Violin<br />

Mark Kaplan, Violin<br />

Alexander Kerr, Violin<br />

Eric Kim, Violoncello<br />

CONGRATULATIONS<br />

to alumnus Dan<br />

Carson on his recent<br />

appointment as<br />

principal bass with<br />

the Alabama<br />

Symphony.<br />

Kevork Mardirossian, Violin<br />

Kurt Muroki, Double Bass<br />

Stanley Ritchie, Violin<br />

Masumi Per Rostad, Viola,<br />

Pacica Quartet<br />

Peter Stumpf, Violoncello<br />

Joseph Swensen, Violin (visiting)<br />

Brandon Vamos, Violoncello,<br />

Pacica Quartet<br />

Stephen Wyrczynski, Viola (chair)<br />

Mimi Zweig, Violin and Viola<br />

CONGRATULATIONS<br />

to Professor Emeritus<br />

Lawrence Hurst on his<br />

recent Distinguished<br />

Achievement Award<br />

given by the<br />

International Society<br />

of <strong>Bassist</strong>s.<br />

2014 AUDITION DATES<br />

Jan. 17 & 18 | Feb. 7 & 8 | March 7 & 8<br />

For a complete list of Jacobs School<br />

faculty, please go to music.indiana.edu.

To<br />

Practice<br />

or<br />

Not<br />

to<br />

Practice...<br />

By Rufus Reid<br />

<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist • 9

When instrument, any instrument, it is<br />

10 •<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist<br />

we are just beginning to play an<br />

hoped we are told how to correctly hold it, how to make<br />

a sound with it, and that we must practice to play it better.<br />

It is also hoped by your parents and/or teacher that<br />

you become so enchanted with the chosen instrument, you<br />

don’t have to be told to continue practicing. When you<br />

begin to notice that you are improving as a player, the<br />

wonderment of discovery truly begins. Please remember<br />

that you practice for yourself because the reality is that<br />

no one really cares if you practice or not. As we mature,<br />

broadening our practicing and listening habits, continuing<br />

to emulate and imitate our music heroes, this process gives<br />

us a very satisfying feeling by enjoying the mere sound that<br />

you make. After 50 years of playing, I still enjoy the ups<br />

and downs, the frustrations, and the successes that this process<br />

of practicing gives us. I even enjoy just looking at my<br />

bass. :-)<br />

When we are young we practice to become really<br />

good. Perhaps one day, you may become a professional<br />

player. It is my opinion that we all should strive to play at<br />

a professional level. Please let it be understood that playing<br />

at a professional level does not mean you will be nor<br />

have to be that individual who makes his or her living as a<br />

professional musician. Those are two totally different subjects<br />

that do not need to be discussed at this time. I hadn’t<br />

thought for several years about making my livelihood as<br />

a professional musician until it just happened. When that<br />

happens, you still have to continue practicing to maintain<br />

that professional level. Everyone should strive to be one<br />

<br />

work diligently to be the best that you can be, because<br />

that is really all that one can do. That is all that YOU need<br />

to care about. You never know when someone is listening<br />

to you, so make every playing situation its optimum.<br />

When we are younger, we feel we have a lot of time, and<br />

you do, to a degree. What you do not have is time to<br />

waste. Remember, no matter how well you play, there is<br />

always more room to learn more.<br />

I loved playing music all through middle school and<br />

high school. I turned down sports if I had to make a choice.<br />

There has never been anything else I wanted to do, but<br />

this has nothing to with deciding to practice. Personally, it<br />

took me three or four years at the beginning stage of my<br />

playing to be “shocked and truly inspired” to learn the real<br />

reason to practice.<br />

In 1964, I was in Japan as a United States Air Force<br />

Band member as a trumpet player. I listened to jazz records<br />

daily, every opportunity I could get. Two years prior<br />

to being shipped to Japan, I began to teach myself the bass,<br />

because I just loved to hear the sound on the recordings of<br />

Paul Chambers, Percy Heath, Willie Ruff, Sam Jones, and<br />

my hero, Ray Brown. While in Japan, there were many<br />

Jazz concerts being presented in Tokyo. In 1965 I saw Ray<br />

terson<br />

Trio and my life was forever changed. To make a<br />

long story short, I met him after the concert. I was in awe.<br />

His playing was amazing. The recordings I had were fabulous,<br />

but to see him up close was simply, astounding. The<br />

crowd was begging for autographs. He noticed me and<br />

said, “Hold my bass, please!” Can you believe it? I couldn’t<br />

either! I held it ever so tightly. After he signed a zillion autographs,<br />

he then let me walk with him back to his hotel a<br />

couple blocks away. I told him I was in the military band<br />

and asked if I could have a lesson with him. He said yes,<br />

and to come back the next morning at 10am. I was at the<br />

hotel at 9am. I called up to the room promptly at 10am<br />

and he told me his room number and said to come up. As<br />

I walked down the hall toward his room, I heard the sound<br />

of the bass being bowed. He had left the door ajar. When<br />

I knocked, he said, “Come on in!” My heart was beating a<br />

mile a minute. As I entered the room, my mouth hit the<br />

<br />

with the bow! This is “The Ray Brown,” PRACTICING? I<br />

didn’t think he still had to do that! Why? He was at the<br />

top of his game, right? Perhaps so, but, I have come to realize<br />

that is one of the main reasons he continued to be at<br />

the top as “Ray Brown,” who was loved by the Jazz com-<br />

<br />

infectious sound. He also had a reputation to uphold that<br />

only he could tear down. I am convinced that he needed<br />

to satisfy himself, as he was being challenged and was expected<br />

to play well all the time.<br />

There are many ingredients and elements melding<br />

together as one to produce a memorable quality sound.<br />

Tone, pitch, dynamics, harmonic sophistication, buoyant<br />

pulse, rhythmic dexterity, interesting creative bass lines,<br />

and engaging solos, constitute the totality of your sound.<br />

Can you practice each of these? Absolutely!<br />

Begin to love your sound. The sound quality you<br />

you don’t<br />

love your sound, why should I? The reality is that no one<br />

really cares if you practice or not, so why do we do it? We<br />

practice because it is incredibly gratifying and satisfying<br />

when we reach those goals that have been eluding us. Our<br />

challenge is to practice so we can sound and play as well as<br />

we did yesterday. Get that concept under control and this<br />

practicing process will grow leaps and bounds. The name<br />

of the game is to maintain those skills you’ve developed<br />

so they are ready when called upon at any given time! If<br />

you wish to become part of the lineage of any genre, you<br />

must convey to your audience that you have done your<br />

homework and you, most certainly, belong on that stage.<br />

Great musicians play with a memorable sound, excellent<br />

dexterity, great intonation, an incredible sense of time, a

controlled sense of dynamics and phrases, and, most importantly,<br />

savvy of the style.<br />

Is it really necessary to practice Jazz?<br />

As a creative jazz bassist, consider yourself an illusionist,<br />

someone who makes one feel and hear what’s not really<br />

there. The listener becomes so engaged by your performance,<br />

they feel a great pulse, but there is no drummer.<br />

They hear wonderful clear harmony, but there is no piano,<br />

<br />

listening to your presentation without the feeling of missing<br />

something or someone. When you are successful achieving<br />

this, you will be remembered and sought after for the clarity<br />

and control you bring to any ensemble. The mindset I<br />

wish you to develop is:<br />

You are the only rhythmic and harmonic substance<br />

there is! You do not need a piano or drummer! We may<br />

want them to play with us, but you don’t need them for<br />

you to play well. If they are doing their job well, they do<br />

not need you either. We bassists have the unique ability to<br />

immediately sabotage every ensemble we play with if we<br />

lose our focus. Yes! Absolutely! In addition to the attributes<br />

of a great musician, the jazz musician must be capable of<br />

thinking quickly by functionally creating new melodic material<br />

to satisfy the sounds of any given structure or form<br />

<br />

make up structures of compositions. I call these structures<br />

“Musical Playgrounds.” Generally speaking, a playground<br />

is a place where all sorts of sports are played. Each sport<br />

-<br />

<br />

rules, fouling all the time, stepping on the lines, etc., we are<br />

asked not to play. Music making is no different. Learn the<br />

rules to be in control of what comes out of your instrument.<br />

It is not a mystery to become an improvising jazz musician.<br />

You just need to know the rules so you can navigate within<br />

the playground successfully. It is NOT rocket science!<br />

What are the ingredients that make up that chord sound<br />

enth”<br />

of a scale, that makes up a chord. There are only<br />

-<br />

<br />

unto themselves. Learn and internalize each sound along<br />

with their respective scales. The rest of the sounds are slight<br />

<br />

key they are in, they all sound the same. The main difference<br />

from just reading music, is, the improvising jazz player<br />

decides how he/she will play by imagining what are the<br />

possibilities. YOU make all of the decisions of what notes<br />

to play, how many notes, what rhythms to use, what dynamics<br />

to use, etc. Thinking of how you want to sound before<br />

you play is crucial to your success! You must practice<br />

how to think, as well. Learn how to construct satisfying<br />

bass lines. Figure them out at the piano. Sing them in your<br />

head. Learn to play them on your bass by listening to how<br />

they sound. These are the very same sounds that Bach,<br />

<br />

etc. used. The sounds that make up these structures are<br />

called Chord Progressions. The style and how these sounds<br />

are presented is what distinguish the different genres from<br />

one another. There are many excellent books available<br />

niques<br />

to play a successful improvised solo in the jazz style.<br />

I’m a bassist.<br />

Why should I be friendly with the piano?<br />

I am NOT asking you to become a pianist, just learn the<br />

basics of where the notes are related to where they sound<br />

on your bass. I was not told how important the piano is<br />

when I began to play music, particularly when I began to<br />

play the bass. I had a good ear and learned quickly, but<br />

that eventually was not enough to really get inside the<br />

music that I loved so much. I had to learn how to identify<br />

the sounds I heard from the symbols I saw. Whatever kind<br />

of music you wish to play, you will be a better musician if<br />

you become very friendly with the piano. Guaranteed! The<br />

piano is the “orchestra” of sounds. You can “see” what the<br />

chord looks like, as well as hear it. Learning the keyboard<br />

and studying harmony will answer all of the questions of<br />

what makes up a chord sound and its harmonic motion.<br />

This is where you can practice your melodies or the phrases<br />

of the music you are working on by very clearly singing<br />

along in tune. Learn the sounds of the basic chords and<br />

their related scales. This functional knowledge will carry<br />

over onto your instrument because you are hearing these<br />

sounds clearly in your head. Again, no one cares if you<br />

practice, or who your teacher was, or if you take lessons<br />

or not, or how long it took you to get it. What matters is<br />

once you get on the bandstand or stage, all they want is to<br />

hear the music clearly and swinging! When these elements<br />

of good practice are present, they will hear consistent, con-<br />

<br />

bass. What more can one ask?<br />

What to practice?<br />

LISTEN to the individual or individuals who inspire you on<br />

a daily basis. Listen to their choice of notes in the chord<br />

progression. Listen how they hook up with the drummer.<br />

Practice on the CONCEPT of the kind of music you are<br />

attempting to play. CONCENTRATE on all of the nuances<br />

you hear in their playing, i.e. their “time feeling,” their<br />

“choice of notes” in a walking bass line, the “pizzicato<br />

sound” being produced in the right hand. Try to incorporate<br />

and emulate by aurally transcribing everything you<br />

hear. The best way to transcribe is to sing and/or whis-<br />

(Continued on Page 12)

tle along with the recording. Eventually try playing along<br />

with the recording. To archive your transcription, write it<br />

<br />

soon be frustrating, in my opinion. You must begin to truly<br />

listen to the sounds coming out of your instrument. Play<br />

everything “slowly and distinctly” so you can hear every-<br />

<br />

that will develop CONSISTENCY in everything you do. If<br />

you are fortunate to have a teacher, practice your assignments.<br />

There are tons of things to practice that tend to<br />

overwhelm us. It is so daunting, we keep putting all of it<br />

off until the next day and, quite often, that day, unfortunately,<br />

never comes. Isolate what is absolutely necessary<br />

and then do half of it, everyday. These are good habits to<br />

form.<br />

When to Practice?<br />

There are four types of practice options, physical,<br />

mental, vocal, visual. As your playing becomes<br />

more mature, practice times will vary, but the four<br />

options are always there for you. The most important<br />

time to physically practice is when you are the<br />

freshest, whenever you think that is for you. Generally<br />

speaking, it is when you wake up after a good<br />

night’s sleep or nap! :-)<br />

Can you practice without the instrument?<br />

Absolutely! The mental, vocal, and visual options are available<br />

to you anytime away from your instrument. In some<br />

respects, I feel these options will help you from wasting precious<br />

time. The visual option will help you overcome the<br />

challenges you may have counting rhythms. When learning<br />

a new song, learn the melody. Then learn the “BIG”<br />

letters of the chord symbol. First, without your instrument,<br />

take a blank manuscript paper. Mark out the appropriate<br />

number of measures with the correct chord symbol<br />

over the top of the staff lines. With a pencil and an eraser,<br />

<br />

notes that represent the sound the chord symbols require<br />

for the song. Use the notes from the chord and/or the notes<br />

<br />

the entire form, play what you have written on your bass.<br />

<br />

<br />

time you will have to contemplate what you have written<br />

and make edits to your satisfaction on the content of your<br />

line. In a real playing situation, you CANNOT STOP and<br />

go back to change something you didn’t like while playing.<br />

Third, continue this process until you are completely<br />

<br />

without stopping. Concentrate on a good time feeling and<br />

good intonation. Generally speaking, reading rhythms in<br />

a designated tempo is more challenging than reading the<br />

notes for many young and inexperienced players. These<br />

two components must be played simultaneously in the<br />

correct tempo to make the phrase musically acceptable.<br />

<br />

comfortable tempo using a metronome. SLOWLY tap on<br />

<br />

able to tap it correctly in the desired tempo. <strong>Next</strong>, SING<br />

the notes. Yes, I said SING! When I am learning or working<br />

on a new melody or phrase, I sing it in my car while driving.<br />

I sing some of the best solos ever in my car. :-) You can<br />

too, if you try! Sing the phrase or passage IN TUNE with<br />

the correct rhythm in the manner you would like to play<br />

it. If you cannot sing it in tune, you will probably not play<br />

it in tune either. Using the piano, sing along as you play<br />

The reality is that no one really cares if you<br />

practice or not, so why do we do it? We<br />

practice because it is incredibly gratifying<br />

and satisfying when we reach those goals<br />

that have been eluding us.<br />

the notes. If you get into the habit of using these mental,<br />

vocal, and visual exercises, you will see a marked improvement<br />

in your playing, believe me. I didn’t believe it either<br />

when I heard double bass virtuoso, Gary Karr speak about<br />

this process in one of his workshops. I was amazed how it<br />

helped me get into the piece much more quickly than I<br />

expected and with more clarity, as well. It will get easier as<br />

you incorporate these habits into your daily life.<br />

How much practice?<br />

After you have a few years under your belt of real playing<br />

situations, to what degree you practice will vary considerably.<br />

It will depend on the demands made upon you<br />

on a daily basis personally and professionally. Remember,<br />

one must keep up with a daily maintenance routine with<br />

scales, challenging etudes, and/or snippets of a composition<br />

you just love to play. Be honest with yourself and stick to<br />

that “real” time frame allocated to practice. Time is a precious<br />

commodity. The organization of your daily practice<br />

habit will train you not to waste time and become more<br />

consistent. This consistency and focus you acquire will roll<br />

over into any and all other music you practice and play.<br />

It will not be a one-time experience. Only you can decide<br />

<br />

playing with a more focused attitude for longer periods of<br />

time with excellent results.<br />

That being said, it is my opinion, after two hours of<br />

physical practice, one should rest the body. If something

you that you are doing something incorrectly. I was told a<br />

very long ago to practice in front of a full-length mirror, as<br />

it will become the best teacher you will ever have. I have<br />

found this to be very true. To this day, I use the mirror constantly<br />

monitoring my overall posture, left and right hand<br />

positions while playing. This is a great habit to acquire.<br />

How long to practice daily?<br />

We all wish we could practice all day long, but in reality,<br />

that isn’t going to happen for most of us! It cannot be<br />

said enough. Time is a precious commodity. When we are<br />

young, we think we will have more time later. WRONG!<br />

If you are still in school, you think you have no time to do<br />

what you want. Believe me, it never gets better when you<br />

get older. So, be honest with yourself and search out that<br />

“real” time slot you can actually do without fail everyday.<br />

<br />

Make a weekly calendar of events you wish or need to<br />

accomplish. If you can actually practice focused material<br />

<br />

improvement.<br />

-<br />

<br />

Five minutes doesn’t sound like much, but it is a very long<br />

time only focusing on one single thing! Before you realize it,<br />

over a short period of practicing in smaller chunks of time,<br />

you will have developed a more focused stamina and will<br />

be capable of focusing for longer periods of time. Once you<br />

<br />

<br />

consecutively before moving on to the next musical item<br />

you wish to learn. This process will help you develop the<br />

high level of playing that you expect from yourself. How<br />

you think of yourself will greatly affect how others think of<br />

<br />

and how, before picking up your bass to play a single note.<br />

Will it be a scale, an arpeggio, and a blues bass line? Which<br />

one? How many octaves? What is the tempo? What dy-<br />

<br />

and what string to begin playing. If using the bow, where<br />

are you placing it on the string? If pizzicato, will it be one<br />

<br />

up your bass and begin playing. Try not to stop the process<br />

until you have completed your assignment. If you do<br />

<br />

and continue from that point. This type of preparation is<br />

important to develop, in my opinion.<br />

1st time:<br />

<br />

<br />

sound, accuracy, and desired tempo?<br />

2nd time:<br />

<br />

Pizzicato string crossings, etc.<br />

3rd time:<br />

Concentrate on playing the passage softly throughout!<br />

4th time:<br />

Concentrate on using varying dynamics and vibrato.<br />

5th time:<br />

Concentrate on the musicality of the sound being produced<br />

and on how beautiful you sound making it!<br />

A mature musician is one who has taken the time to study<br />

the tradition of any musical idiom before he/she can truly<br />

conceptualize that music.<br />

<br />

learning something new. Enjoy the discovery.<br />

Rufus Reid’s major professional<br />

career began in Chicago and<br />

continues since 1976 in New<br />

York City. He has toured and recorded<br />

with Eddie Harris, Nancy<br />

Wilson, Harold Land & Bobby<br />

Hutcherson, Lee Konitz, and<br />

countless others. He continues to<br />

enjoy associations with Tim Hagans,<br />

Bob Mintzer, Frank Wess,<br />

Marvin Stamm, Benny Golson.<br />

Rufus Reid is equally<br />

known as an exceptional educator.<br />

Dr. Martin Krivin and Reid<br />

created the Jazz Studies & Performance Program at William<br />

Paterson University. Reid retired aer 20 years, but continues<br />

to teach, conducting Master Classes, workshops, and residencies<br />

around the world.<br />

<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist • 13

ALWAYS ASSUME THAT YOU ARE THE ONLY HARMONIC AND RHYTHM SUBSTANCE.<br />

14 •<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist<br />

The Jazz <strong>Bassist</strong>’s Mindset<br />

Develop a CONCEPT! CONCENTRATE on that concept.<br />

Your CONFIDENCE will you develop CONSISTENCY!<br />

• CONSISTENCY OF<br />

TONE PRODUCTION<br />

• A GREAT PULSE<br />

(Time Feeling)<br />

• INTONATION<br />

• HARMONICE AWARENESS<br />

• REPERTOIRE<br />

• SENSE OF<br />

PHRASE AND DYNAMICS<br />

• • ASSESSMENT<br />

ASSESMENT OF YOUR<br />

MUSICAL SETTING<br />

via Rufus Reid<br />

75% OF YOUR CONCENTRATION<br />

IS “NOT” ON YOU!!<br />

THIS WILL DEVELOP YOUR<br />

“PERIPHERAL HEARING”<br />

YOU<br />

CHORDAL<br />

INSTRUMENTS<br />

PIANO<br />

GUITAR<br />

VIBRAPHONE<br />

SYNTHS<br />

ANY<br />

PERCUSSION<br />

INSTRUMENTS<br />

FRONT LINE<br />

ANY HORN<br />

COMBINATION<br />

A MATURE MUSICIAN IS ONE THAT HAS TAKEN THE TIME TO STUDY THE TRADITION OF<br />

ANY MUSICAL IDIOM BEFORE HE/SHE CAN TRULY CONCEPTUALIZE THAT MUSIC!

Transition works on a range in the bass that is extremely useful and should be<br />

incredibly comfortable to play in. If you can master the 1-octave harmonics and the<br />

way you get around them from above and below, this should have a positive eect<br />

on a huge amount of solo literature for the bass. This applies to Bach, concertos and<br />

a host of other pieces both original and transcribed.<br />

Double stops are challenging on the bass, because you need to figure out how how<br />

to distribute bow weight between two strings, as well as finger/arm weight, and you<br />

must manage tension levels very carefully. Harmonics are a good introduction to<br />

this, followed by using one harmonic and one stopped note.<br />

Working on Transition, if you have not done so already, will enable you to become a<br />

much more versatile bass player and add comfort to your thumb position skill set.<br />

- Ranaan Meyer<br />

<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist • 15

16 •<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist

<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist • 17

Stronger is something that will give you a fundamental of rhythm that is extremely important.<br />

The notes start out sporadic and move towards a flow. Get out your metronome and<br />

keep on track, because it will feel like dierent tempi throughout this piece. That’s the thing<br />

I notice about running notes into slower notes. Going from half to quarter to eighth to sixteenth,<br />

you will find yourself adjusting to the metronome based on your perspective of where<br />

the beat is. When you play with people, you will find a dierent set of skills necessary. I know<br />

in playing with Time for Three that we are always pushing ahead, leaning on the front end of<br />

the beat. The metronome is a fundamental, but it isn’t something my group can depend on.<br />

Pay close attention to your tendencies, too - learn whether you tend to speed up or slow down<br />

and decide whether the music is calling for that (certain settings don’t let you do it at all, such<br />

as orchestra playing or auditions).<br />

Finally, I’m introducing a technique that I find revolutionary - moving from a note to a slap<br />

in the space of one sixteenth note, as in measure 6. It will probably feel unusual, maybe a bit<br />

diicult at first. Most slaps in bass playing occur on the eighth note, and it is totally common<br />

to need some time to acclimate to this technique. Once you have it though, you will find it is<br />

extremely helpful, not to mention a lot of fun!<br />

FACULTY<br />

Terell Stafford, Chair,<br />

Instrumental Studies Department<br />

Eduard Schmieder,<br />

L. H. Carnell Professor of Violin,<br />

Artistic Director for Strings<br />

Luis Biava*, Music Director,<br />

Symphony Orchestra<br />

Double Bass<br />

Joseph Conyers*<br />

John Hood*<br />

Robert Kesselman*<br />

Anne Peterson<br />

*Current member of<br />

The Philadelphia Orchestra<br />

For more information, please contact:<br />

215-204-6810 or music@temple.edu<br />

www.temple.edu/boyer<br />

18 •<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist<br />

PROGRAMS<br />

B.M.: Performance<br />

B.M.: Composition<br />

B.M.: Music Education<br />

B.M.: Music History<br />

B.M.: Music Theory<br />

B.M.: Music Therapy<br />

M.M.: Performance<br />

M.M.: Composition<br />

M.M.: Music Education<br />

M.M.: Music History<br />

M.M.: Music Theory<br />

M.M.: String Pedagogy<br />

M.M.T.: Music Therapy<br />

D.M.A.: Performance<br />

Ph.D.: Music Education<br />

Ph.D.: Music Therapy<br />

Professional Studies Certificate<br />

ENSEMBLE OPPORTUNITIES<br />

> Temple University Symphony Orchestra<br />

> Opera Orchestra<br />

> Sinfonia Chamber Orchestra<br />

> Contemporary Music Ensemble<br />

> Early Music Ensemble<br />

> String Chamber Ensembles<br />

Philadelphia, PA<br />

- Ranaan Meyer

S = Slap<br />

H = Hammer On<br />

P = Pull Off<br />

x = muted Note<br />

B = "Bass Bump" Use fist to make a bass drum sound on the body of the bass<br />

x & note stem = slap and play pitch simultaneously<br />

Double Bass<br />

6<br />

9<br />

?#<br />

?#<br />

12<br />

?#<br />

15<br />

?#<br />

18<br />

?#<br />

22<br />

?#<br />

H<br />

?# 4<br />

œ œ ¿ œ<br />

Bass Part Secrets from TF3's Stronger<br />

S<br />

pizz.<br />

∑<br />

¿ j ‰ Œ<br />

H<br />

B B B S mute H<br />

¿ ¿ œ œ S<br />

‰ j ‰ Œ ‰<br />

¿<br />

S S<br />

G D G D G D<br />

G D G D<br />

Copyright © 2013<br />

H<br />

S S<br />

H S S H S S H S S<br />

œ œ ¿ œ<br />

H S S 0 H<br />

œ œ<br />

¿ œ<br />

¿<br />

¿<br />

œ œ<br />

¿ œ<br />

¿<br />

S S 0 H<br />

slap & pitch sim.<br />

¿<br />

œ ‰ œ J ¿<br />

œ œ œ œ ¿<br />

œ œ œ œ ¿<br />

Ó Œ ‰ ≈ ¿ r ¿ j ‰ Œ Ó Œ ¿ j ‰ Œ ¿<br />

¿ ¿ œ œ ¿ œ<br />

¿<br />

¿ ¿ œ œ ¿ œ<br />

œ œ œ œ œ<br />

¿ œ<br />

¿<br />

œ œ œ œ œ<br />

¿ œ<br />

¿<br />

¿<br />

œ Œ<br />

œ œ<br />

¿<br />

¿<br />

S S 0 H<br />

S S 0 H<br />

¿ ¿ œ œ ¿ œ<br />

¿<br />

¿ ¿ œ œ ¿ œ<br />

œ œ œ œ œ œ œ<br />

¿<br />

œ œ<br />

¿ œ<br />

¿<br />

œ œ œ œ ¿<br />

¿<br />

Ranaan Meyer<br />

S S 0 H<br />

S<br />

œ œ œ œ œ<br />

¿ œ<br />

¿<br />

<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

P<br />

¿ ¿<br />

œ<br />

‰ œ<br />

¿ ¿<br />

J r ≈<br />

¿<br />

œ ‰ œ J ¿<br />

œ œ œ œ ¿<br />

¿ ¿<br />

œ œ œ<br />

œ œ œ œ œ œ œ<br />

œ œ¿ œ<br />

¿ œ œ œ œ<br />

¿œ œ ¿ ¿ œ œ # œ œ<br />

¿œ œ ¿ ¿ œ œ nœ œ<br />

¿œ œ ¿ ¿ œ œ<br />

¿œ<br />

œ œ œ ¿ ¿ œ œ œ œ<br />

¿œ œ ¿ ¿ œ œ # œ œ<br />

¿œ œ ¿ œ œ œ œ nœ œ<br />

¿œ œ ¿ ¿ œ œ<br />

¿œ<br />

assist • 19

20 •<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist<br />

MAKE<br />

practice<br />

Perfect<br />

By<br />

David<br />

Allen<br />

Moore

Practice<br />

is universally recognized as<br />

a musician’s primary tool<br />

-<br />

<br />

and hallowed performing venues (see How to get<br />

to Carnegie Hall-<br />

<br />

converse in braggadocios tones about how many<br />

hours they’ve practiced rather than what was ac-<br />

<br />

I hope to share with you a few of the fundamen-<br />

<br />

<br />

practice techniques. Practice is a time to master<br />

<br />

<br />

of practicing itself such that we can be said to be<br />

-<br />

<br />

analysis. In other words: <strong>Practicing</strong> the Practice of<br />

Practice Practice.<br />

Time Management<br />

Before one can even begin to address the content<br />

<br />

conditions that can ensure that the session itself will<br />

-<br />

<br />

on their time. The total<br />

time available in any<br />

given day could be visualized<br />

as an empty jar<br />

that we then begin to<br />

<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

ter<br />

that you pour into the jar once all other space is<br />

<br />

viewed with the same commitment and dedication<br />

ence<br />

is that the practice schedule is self-imposed<br />

and self-motivated.<br />

Practice time needs to be scheduled into a<br />

erence<br />

as demands placed on you by the outside<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

there is the question of how to organize the time<br />

<br />

<br />

about 50 minutes of practice to 10 minutes of rest.<br />

<br />

of the time into three sections: technique (scales/<br />

<br />

solo repertoire. Each section would be roughly the<br />

same duration (for the arithmetically-challenged: in<br />

<br />

minutes rest for each section yielding a total of 2.5<br />

hours practice and 30 minutes of rest.) Proportions<br />

<br />

circumstances (i.e. more time on orchestral reper-<br />

<br />

time to solo rep in preparation for a recital.) Endur-<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

Goal Setting<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

what will be prac-<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

ticed in advance<br />

of the actual practice<br />

session. This<br />

can be as little as a<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

will require the purchase of an additional piece of<br />

equipment that may not currently be part of your<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

will provide an invaluable resource for future plan-<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

setting is to always set yourself up to succeed. The<br />

(Continued on Page 22)

simplest and most direct way to accomplish this is<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

your talents would be much more effectively and<br />

<br />

two-word phrase can be applied to the beginning<br />

of any practice session goal to ensure success ev-<br />

-<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

are things that can surely be accomplished as they<br />

don’t presuppose the amount of progress to be<br />

made (if any). The most challenging times during<br />

parent<br />

stasis. I am comforted during these times by<br />

<br />

est<br />

position that they can currently achieve and<br />

<br />

a platform of support. They are to repeat this pro-<br />

ing<br />

that they will have torn off one page of the top<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

with a feeling of accomplishment and momentum<br />

that you can build on rather than feeling that the<br />

<br />

to the bottom of the hill.<br />

C.R.A.F.T. Cycle vs. Vomit Cycle<br />

<br />

<br />

how to go about achieving those goals. Too often<br />

students practice in a manner that I affectionately<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

This glorious procedure is then followed by the implementation<br />

of the ever-popular practice tech-<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

Cing<br />

for/paying attention to before you start play-<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

22 •N L assist<br />

ext evel<br />

<br />

the sheer volume of information coming at you.<br />

R<br />

Analysis: Compare your conception and your re-<br />

<br />

<br />

Fine T<br />

ly<br />

highlight where you need additional input (i.e. assist<br />

in the formulation of questions for your teacher at<br />

<br />

developed concept and are aware of what needs<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Semantics<br />

<br />

but we rarely give much thought to the words and<br />

<br />

the practice room. I feel very fortunate to have<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

we set up for ourselves when dealing with material<br />

<br />

would propose we add to the list of words to avoid is<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

passage or instrumental technique. I suggest that<br />

we rephrase this in a positive and aspirational light:<br />

<br />

dialogue that we have with ourselves during prac-<br />

<br />

ternally<br />

that I wouldn’t say out loud to someone else<br />

during a master class.

Dynamic Forms<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

in order to solve a variety of technical challenges<br />

(not<br />

-<br />

<br />

terns<br />

to achieve desired results. Dance and martial<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

routines. The root of many technical issues involves<br />

<br />

<br />

ing<br />

a large shift. The customary procedure involves<br />

<br />

determined solely by whether or not the target pitch<br />

-<br />

tinued<br />

repetition we will intuitively increase our percentage<br />

of success until it reaches a reliable state.<br />

Redefining Relevant<br />

Strings Faculty<br />

Division of Classical Performance Studies<br />

Violin: <br />

<br />

<br />

Viola: <br />

Cello: <br />

Bass: <br />

Harp: <br />

Explore why we are unique among the finest music schools in the world.<br />

usc.edu/music | facebook.com/uscthornton<br />

<br />

of much frustration in the practice room.<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

etc.)<br />

• The note sounds in tune.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

(Conclusion on Page 25)<br />

Our students define success;<br />

our priority is to get them there.<br />

With a continuing legacy of renowned faculty-artists,<br />

we have a keen eye towards the future and understand<br />

the new paradigms of a career in classical music.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

All this within Los Angeles, the music capital of the<br />

21st century.

A<br />

24 •<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist<br />

NEW FEATURE<br />

Review assist<br />

ext evel<br />

N L<br />

The DPA d:vote 4099B microphone could pretty much<br />

be called my new best friend! Now that’s not to put<br />

down Nick and Zach, my brothers-in-arms in Time<br />

for Three, but that’s mainly because our whole group<br />

uses and loves microphones by DPA. I want to lay<br />

out some of the reasons why this mic is making a<br />

huge difference in my touring life.<br />

One of the bigger challenges of playing live in big<br />

rooms is getting something that resembles your un-<br />

<br />

pickups and more than a few mics before, but the<br />

<br />

an authentic bass sound. Considering my style, it’s<br />

incredible that I’m able to get the best arco and pizz<br />

sound from this one device out of anything I’ve ever<br />

used. I don’t just play on the strings, and I’m happy<br />

to say the mic captures the percussion of hitting,<br />

smacking, or slapping the bass just as well as traditional<br />

playing.<br />

From a traveling musician’s standpoint, the 4099B is<br />

really convenient too. I like the carrying case for its<br />

small size and very safe construction. It currently<br />

slots into a larger case with my other sound gear,<br />

but you can take it with the rest of your rig and not<br />

worry about losing your investment. It’s easy to plug<br />

<br />

in high pressure situations. I have gotten great feedback<br />

from the sound guys and gals I work with too<br />

<br />

is so important! You have to make sure the people in<br />

charge of your sound have the control they need to<br />

be great artists too.<br />

If you are serious about your live sound, the d:vote<br />

4099B by DPA is a must have. Investing in an easyto-use,<br />

incredible sounding, not to mention cool-looking<br />

microphone might be the best choice you make<br />

<br />

-Ranaan Meyer<br />

The stage is set<br />

DPA 4099<br />

for Bass and Cello<br />

Gain without pain<br />

The d:vote 4099 Clip Microphones cover the entire<br />

orchestra, providing highly directional, truly natural sound<br />

and high gain before feedback.<br />

www.dpamicrophones.com/dvote

contact need to move due to the change in regis-<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

your body aware of the starting and ending posi-<br />

<br />

the issue by also trying to transition between them<br />

<br />

step would be to repeat this sequence and actually<br />

<br />

<br />

between notes to fully visualize the new position in<br />

and form.)<br />

curred<br />

when moving from one position to the other<br />

– even if the notes sound in tune (remember: we<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

Final Thoughts<br />

-<br />

-<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

times<br />

they need to be abandoned altogether in<br />

favor of banging your head repeatedly against an<br />

-<br />

<br />

GO<br />

PRACTICE<br />

David Allen Moore is 4th chair double<br />

bass of the Los Angeles Philharmonic<br />

while also serving as a professor<br />

at the USC Thornton School<br />

of Music, the school from which<br />

he graduated in 1993. Moore was<br />

also a member of the Houston<br />

Symphony from 1993-1999. He regularly<br />

performs with San Diego’s<br />

Mainly Mozart Festival and the Los<br />

Angeles Philharmonic’s New Music<br />

Group. He has presented master<br />

classes at Curtis, Juilliard, Rice,<br />

and NEC. His former students are<br />

present in professional orchestras<br />

in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Europe. Moore<br />

is also a faculty member at Domaine Forget, the summer<br />

music festival in Québec, Canada.<br />

<strong>Next</strong> <strong>Level</strong><br />

assist • 25