Teacher Learning in a Community of Practice: A Case Study of ...

Teacher Learning in a Community of Practice: A Case Study of ... Teacher Learning in a Community of Practice: A Case Study of ...

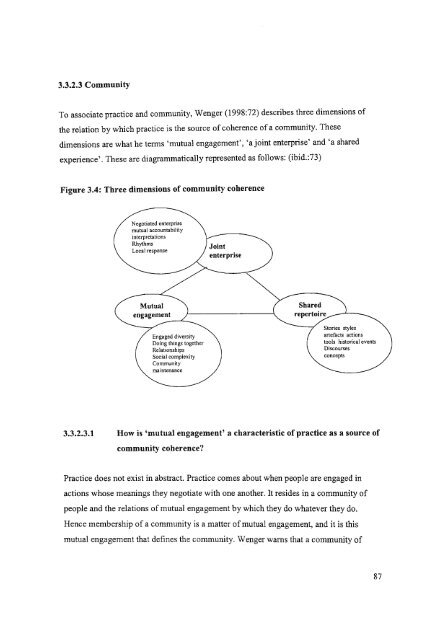

3.3.2.3 Community To associate practice and community, Wenger (1998:72) describes three dimensions of the relation by which practice is the source ofcoherence ofa community. These dimensions are what he tenns 'mutual engagement', 'a joint enterprise' and 'a shared experience'. These are diagrammatically represented as follows: (ibid.:73) Figure 3.4: Three dimensions of community coherence Negotiated enterprise mutual accountability interpretations Rhythms LocaI response Mutual engagement Engaged diversity Doing things together Relationships Social complexity Community maintenance Stories styles artefacts actions tools historical events Discourses concepts 3.3.2.3.1 How is 'mutual engagement' a characteristic of practice as a source of community coherence? Practice does not exist in abstract. Practice comes about when people are engaged in actions whose meanings they negotiate with one another. It resides in a community of people and the relations ofmutual engagement by which they do whatever they do. Hence membership ofa community is a matter ofmutual engagement, and it is this mutual engagement that defines the community. Wenger warns that a community of 87

practice is not just an aggregate ofpeople and is not a synonym for an arbitrary group, team or network (Wenger 1998). An essential component ofany practice is essentially what it takes to cohere to make mutual engagement possible. Inclusion in what matters is a prerequisite for being engaged in a community's practice. The kind ofcoherence that transforms mutual engagement into a community ofpractice requires concerted effort. Wenger (1998) describes the concept 'community maintenance' as being an 'intrinsic part' ofany practice. However, because it may be much less visible than the more instrumental aspects ofthat practice, it can be easily undervalued or not recognised (ibid.). Proactive steps have to be taken to ensure mutual engagement is transformed into a community of practice (ibid.). Mutual engagement in a community ofpractice does not entail a homogenous grouping; in fact, the mutual engagement in a practice is more productive when there is diversity in the grouping. Not only are members ofa community ofpractice different, but also working together creates differences as well as similarities. In as much as they develop shared ways ofdoing things, members also distinguish themselves or gain a reputation. Each participant in a community ofpractice finds a unique place and gains a unique identity, which is both further integrated and further defined in the course ofengagement in the community ofpractice. ':Homogeneity is neither a requirement for, nor the result of, the development of a community ofpractice" (Wenger 1998:76). Mutual engagement involves not merely the competence of an individual participant but the competence ofall participants. Mutual engagement draws on what participants do and what they know as well as their ability to connect meaningfully to what they do not do and do not know, that is, the ability to connect meaningfully to the contributions and knowledge ofothers. It is therefore important to know how to give and receive help. Developing a shared practice depends on mutual engagement. 88

- Page 51 and 52: Learning is social in nature (Putma

- Page 53 and 54: Constant reflection on and understa

- Page 55 and 56: Teachers drew on their membership i

- Page 57 and 58: The above arguments about the lack

- Page 59 and 60: change. She highlights the importan

- Page 61 and 62: Differences in the cultures oflearn

- Page 63 and 64: persons and is not considered solel

- Page 65 and 66: and offers insights into how learni

- Page 67 and 68: America. Goodson (1992) and Calderh

- Page 69 and 70: learned meaning and value for them

- Page 71 and 72: 'accommodation' and intimates that

- Page 73 and 74: staffroom and a 'pragmatic' teacher

- Page 75 and 76: Davisson (1984), Lumsden and Scott

- Page 77 and 78: directive in that it guides choices

- Page 79 and 80: economic discourse, the economics p

- Page 81 and 82: • Understand and promote the impo

- Page 83 and 84: 2.7 CONCLUSION This chapter began b

- Page 85 and 86: (Walford 2001; Anderson 1999). With

- Page 87 and 88: • It places value on the research

- Page 89 and 90: The main research question in this

- Page 91 and 92: Lave and Wenger emphasise the centr

- Page 93 and 94: 3.3.2 The Work ofWenger (1998): Com

- Page 95 and 96: agree with the way it takes place o

- Page 97 and 98: Figure 3.3: Refined intersection of

- Page 99 and 100: eflecting. The ability of a communi

- Page 101: object to something that in reality

- Page 105 and 106: system or institution and the influ

- Page 107 and 108: 3.3.2.4 Learning Practice has to be

- Page 109 and 110: new possibilities for meaning. Brok

- Page 111 and 112: These characteristics indicate that

- Page 113 and 114: engage with one another and acknowl

- Page 115 and 116: A structural model ofa community of

- Page 117 and 118: who were regarded as peripheral. A

- Page 119 and 120: Ideally I would have wanted teacher

- Page 121 and 122: they represent key ingredients in s

- Page 123 and 124: that the Wenger framework presents

- Page 125 and 126: more useful and effective than part

- Page 127 and 128: 3.6 CONCLUSION This chapter provide

- Page 129 and 130: • While my professional input int

- Page 131 and 132: • Cycle ofhypothesis and theory b

- Page 133 and 134: observer played themselves out. A c

- Page 135 and 136: organised events and linked communi

- Page 137 and 138: In keeping with ethnographic princi

- Page 139 and 140: In this qualitative study, my inter

- Page 141 and 142: collection. He questions whether co

- Page 143 and 144: physical context, the complex body

- Page 145 and 146: completed, final text: rather, they

- Page 147 and 148: the teacher over classroom events (

- Page 149: 'connoisseurship'. I realised that

3.3.2.3 <strong>Community</strong><br />

To associate practice and community, Wenger (1998:72) describes three dimensions <strong>of</strong><br />

the relation by which practice is the source <strong>of</strong>coherence <strong>of</strong>a community. These<br />

dimensions are what he tenns 'mutual engagement', 'a jo<strong>in</strong>t enterprise' and 'a shared<br />

experience'. These are diagrammatically represented as follows: (ibid.:73)<br />

Figure 3.4: Three dimensions <strong>of</strong> community coherence<br />

Negotiated enterprise<br />

mutual accountability<br />

<strong>in</strong>terpretations<br />

Rhythms<br />

LocaI response<br />

Mutual<br />

engagement<br />

Engaged diversity<br />

Do<strong>in</strong>g th<strong>in</strong>gs together<br />

Relationships<br />

Social complexity<br />

<strong>Community</strong><br />

ma<strong>in</strong>tenance<br />

Stories styles<br />

artefacts actions<br />

tools historical events<br />

Discourses<br />

concepts<br />

3.3.2.3.1 How is 'mutual engagement' a characteristic <strong>of</strong> practice as a source <strong>of</strong><br />

community coherence?<br />

<strong>Practice</strong> does not exist <strong>in</strong> abstract. <strong>Practice</strong> comes about when people are engaged <strong>in</strong><br />

actions whose mean<strong>in</strong>gs they negotiate with one another. It resides <strong>in</strong> a community <strong>of</strong><br />

people and the relations <strong>of</strong>mutual engagement by which they do whatever they do.<br />

Hence membership <strong>of</strong>a community is a matter <strong>of</strong>mutual engagement, and it is this<br />

mutual engagement that def<strong>in</strong>es the community. Wenger warns that a community <strong>of</strong><br />

87