Spotlight: Nick Joerling shifts gears Techno File - Ceramic Arts Daily

Spotlight: Nick Joerling shifts gears Techno File - Ceramic Arts Daily

Spotlight: Nick Joerling shifts gears Techno File - Ceramic Arts Daily

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

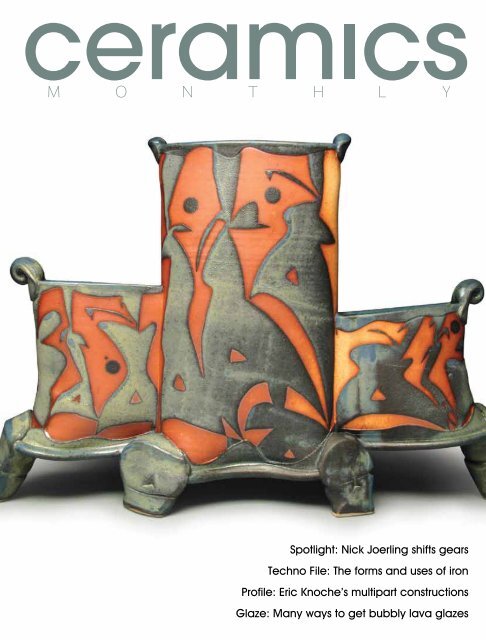

<strong>Spotlight</strong>: <strong>Nick</strong> <strong>Joerling</strong> <strong>shifts</strong> <strong>gears</strong><br />

<strong>Techno</strong> <strong>File</strong>: The forms and uses of iron<br />

Profile: Eric Knoche’s multipart constructions<br />

Glaze: Many ways to get bubbly lava glazes

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 1

2 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org

Manufacturer of the Famous GEIL Downdraft Gas Kiln Presents<br />

The NEW State-of-the-Art<br />

Front-loading Electric Kiln<br />

Model EHW-12<br />

• 12 cu. ft. (27” W x 27” D x 36” H)<br />

• 3 zone controller (Bartlett Controller<br />

may be mounted remotely)<br />

• Built-in vent system<br />

• Geil Guard coating<br />

• Ventilated Shell<br />

• Cone 10 (2350 Deg. F)<br />

• Door Safety Interlock<br />

• Drawer-type elements that connect in<br />

the rear of the kiln<br />

$7,500<br />

FOB Huntington Beach, CA<br />

Easy Change<br />

Element System<br />

If you can open a drawer, you can<br />

change these elements.<br />

• NO Pins<br />

• NO Rods<br />

• NO Sagging<br />

See this kiln at NCECA - Booths 413, 415, 417<br />

GEIL KILNS<br />

www.kilns.com 800 • 887 • 4345 geil@kilns.com<br />

GEIL Firing Workshop in May • Check Our Website for Details<br />

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 3

4 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 5

6 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

m o n t h l y<br />

Publisher Charles Spahr<br />

Editorial<br />

editorial@ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

telephone: (614) 794-5867<br />

fax: (614) 891-8960<br />

editor Sherman Hall<br />

associate editor Jessica Knapp<br />

assistant editor Holly Goring<br />

editorial assistant Erin Pfeifer<br />

technical editor Dave Finkelnburg<br />

online editor Jennifer Poellot Harnetty<br />

Advertising/Classifieds<br />

advertising@ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

telephone: (614) 794-5834<br />

fax: (614) 891-8960<br />

classifieds@ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

telephone: (614) 794-5843<br />

advertising manager Mona Thiel<br />

advertising services Jan Moloney<br />

Marketing<br />

telephone: (614) 794-5809<br />

marketing manager Steve Hecker<br />

Subscriptions/Circulation<br />

customer service: (800) 342-3594<br />

ceramicsmonthly@pubservice.com<br />

Design/Production<br />

production editor Cyndy Griffith<br />

production assistant Kevin Davison<br />

design Boismier John Design<br />

Editorial and advertising offices<br />

600 Cleveland Ave., Suite 210<br />

Westerville, Ohio 43082<br />

Editorial Advisory Board<br />

Linda Arbuckle; Professor, <strong>Ceramic</strong>s, Univ. of Florida<br />

Scott Bennett; Sculptor, Birmingham, Alabama<br />

Val Cushing; Studio Potter, New York<br />

Dick Lehman; Studio Potter, Indiana<br />

Meira Mathison; Director, Metchosin Art School, Canada<br />

Bernard Pucker; Director, Pucker Gallery, Boston<br />

Phil Rogers; Potter and Author, Wales<br />

Jan Schachter; Potter, California<br />

Mark Shapiro; Worthington, Massachusetts<br />

Susan York; Santa Fe, New Mexico<br />

<strong>Ceramic</strong>s Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is published monthly,<br />

except July and August, by <strong>Ceramic</strong> Publications Company; a<br />

subsidiary of The American <strong>Ceramic</strong> Society, 600 Cleveland Ave.,<br />

Suite 210, Westerville, Ohio 43082; www.ceramics.org. Periodicals<br />

postage paid at Westerville, Ohio, and additional mailing offices.<br />

Opinions expressed are those of the contributors and do<br />

not necessarily represent those of the editors or The American<br />

<strong>Ceramic</strong> Society.<br />

The publisher makes no claim as to the food safety of published<br />

glaze recipes. Readers should refer to MSDS (material safety<br />

data sheets) for all raw materials, and should take all appropriate<br />

recommended safety measures, according to toxicity ratings.<br />

subscription rates: One year $34.95, two years $59.95.<br />

Canada: One year $40, two years $75. International: One year<br />

$60, two years $99.<br />

back issues: When available, back issues are $7.50 each,<br />

plus $3 shipping/handling; $8 for expedited shipping (UPS<br />

2-day air); and $9 for shipping outside North America. Allow<br />

4–6 weeks for delivery.<br />

change of address: Please give us four weeks advance<br />

notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new<br />

address to: <strong>Ceramic</strong>s Monthly, Circulation Department, P.O. Box<br />

15699, North Hollywood, CA 91615-5699.<br />

contributors: Writing and photographic guidelines<br />

are available online at www.ceramicsmonthly.org.<br />

indexing: Visit the <strong>Ceramic</strong>s Monthly website at<br />

www.ceramicsmonthly.org to search an index of article titles and<br />

artists’ names. Feature articles are also indexed in the Art Index,<br />

daai (design and applied arts index).<br />

copies: Authorization to photocopy items for internal<br />

or personal use beyond the limits of Sections 107 or 108 of<br />

the U.S. Copyright Law is granted by The American <strong>Ceramic</strong><br />

Society, ISSN 0009-0328, provided that the appropriate fee<br />

is paid directly to Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222<br />

Rosewood Dr., Danvers, MA 01923, USA; (978) 750-8400;<br />

www.copyright.com. Prior to photocopying items for classroom<br />

use, please contact Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.<br />

This consent does not extend to copying items for general<br />

distribution, or for advertising or promotional purposes, or to<br />

republishing items in whole or in part in any work in any format.<br />

Please direct republication or special copying permission requests<br />

to the Publisher, The <strong>Ceramic</strong> Publications Company; a subsidiary<br />

of The American <strong>Ceramic</strong> Society, 600 Cleveland Ave., Suite 210,<br />

Westerville, Ohio 43082, USA.<br />

postmaster: Send address changes to <strong>Ceramic</strong>s Monthly,<br />

P.O. Box 15699, North Hollywood, CA 91615-5699. Form 3579<br />

requested.<br />

Copyright © 2011, The <strong>Ceramic</strong> Publications Company; a subsidiary<br />

of The American <strong>Ceramic</strong> Society. All rights reserved.<br />

www.ceramicsmonthly.org

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 7

contents<br />

march 2011 volume 59, number 3<br />

8 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

22<br />

editorial<br />

10 From the Editor Sherman Hall<br />

12 letters<br />

techno file<br />

14 All About Iron by John Britt<br />

Iron can be many things—many of which are not brown.<br />

tips and tools<br />

16 Rolling Reclaim by Donna Jones<br />

Saving clay and saving space are both great ideas.<br />

exposure<br />

18 Current Exhibitions<br />

glaze<br />

50 Silicon Carbide: the Stuff of Stars by Mark Chatterley<br />

For those of you who don’t think bubbles and craters are glaze flaws.<br />

reviews<br />

58 Embracing Personal Expressions<br />

in Contemporary Japanese tea Wares<br />

Exhibitions at Musee Tomo in Tokyo and the Craft Gallery in the National<br />

Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. Reviewed by Naomi Tsukamoto<br />

60 A System of Generosity: John GradeÕ s Circuit<br />

at Davidson Galleries in Seattle, Washington, and Cynthia Reeves Gallery<br />

in New York City. Reviewed by Ben Waterman<br />

resources<br />

77 Call for Entries<br />

Information on submitting work for exhibitions, fairs, and festivals.<br />

78 Classifieds<br />

Looking to buy? Looking to Sell? Look no further.<br />

79 Index to Advertisers<br />

spotlight<br />

80 nick <strong>Joerling</strong> Shifts Gears<br />

Why would someone change what is arguably a very successful,<br />

established body of work in order to move in another direction?

clay culture<br />

26 one hundred Jars<br />

Daniel Johnston’s 90-cubic-foot kiln transformed 11,000 pounds of clay, 25 gallons of<br />

glaze and slip, 30 cords of wood, and 800 pounds of salt into 100 large glazed jars—<br />

for just one sale.<br />

28 low high-tech<br />

As it turns out, clay (specifically porcelain) is the perfect material for making a<br />

gramophone that amplifies your iPod.<br />

30 Pots in Action<br />

Making a living from your work not only takes tremendous skill but also creative<br />

marketing. Ayumi Horie has embraced elements of social networking to build a record<br />

of off-the-cuff action shots of her work. The result is both humorous and smart.<br />

32 the Periodic table of Videos<br />

Science videos featuring common elements that are also near and dear to our studios,<br />

which discuss their various properties as they relate to everyday life, or life in the lab.<br />

studio visit<br />

34 lorna meaden, Durango, Colorado<br />

How one potter scraped and planned and labored to carve out a life making pots.<br />

features<br />

38 An Unsaid Quality by Janet Koplos<br />

A retrospective exhibition of Toshiko Takaezu’s work prompts this discussion of the<br />

relationship between depth and brevity, stillness and meaning.<br />

44 minkyu lee: hidden Structure Revealed by David Damkoehler<br />

A ceramic sculptor focuses on defining the parts of his work that are not actually<br />

there, encouraging viewers to complete the work in their minds.<br />

48 mFA Factor: University of South Carolina<br />

A three-year program with teaching assistant opportunities as well as job placement.<br />

52 Eric Knoche: Points of Connection by Katey Schultz<br />

What might seem like separate bodies of work to the casual observer actually<br />

form a consistent pursuit of ideas and expression for this potter and sculptor.<br />

monthly methods Buried in Fire by Eric Knoche<br />

57 Paul Soldner, 1921Ð2 010 by Doug Casebeer<br />

One of the great pioneers of modern studio practice and ceramic exploration,<br />

and arguably one of the most well-respected and well-known ceramics teachers<br />

of our time, leaves a legacy of individuality, freedom of creative exploration, and<br />

artistic honesty.<br />

cover: Compound pocket vase, 12 in. (30 cm) in height,<br />

thrown and altered stoneware with resist glaze decoration,<br />

by <strong>Nick</strong> <strong>Joerling</strong>, Penland, North Carolina; page 80.<br />

52<br />

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 9

from the editor<br />

respond to shall@ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

Well, here we are, folks, at the relaunch issue<br />

of <strong>Ceramic</strong>s Monthly. Most of you know by<br />

now that we have been working on this for<br />

quite some time, and it would be redundant<br />

for me to list all of the things we have tweaked<br />

and shuffled in order to arrive here (you can<br />

read my letter from last month if you want<br />

the list), so I suggest you dive right<br />

in, flip through and have a good<br />

look. Honestly, anything I would<br />

have to say about the merits of this<br />

issue matters very little at this point.<br />

All the work has been done, the tests<br />

have been run, everything was formed,<br />

dried, glazed, and fired, and here we<br />

are at the unloading of the kiln: fingers<br />

crossed, held breath, slightly increased<br />

heart rate, feeling the lid hoping it’s<br />

just cool enough to open, peeking at<br />

the top shelf, telling ourselves not to<br />

jump to any conclusions, retracing<br />

all of our steps in loading, trying to<br />

keep our unrealistic expectations in<br />

check while still believing that this<br />

will be the one.<br />

Of course, like anyone who really<br />

knows how to have a good kiln opening,<br />

we’ve already opened the kiln,<br />

put the seconds back in the studio<br />

for reglazing, taken a hammer to the<br />

duds, and gathered what we think are<br />

the best mix of pieces and laid them<br />

out for the sale. Come on, it’s not a trick, it’s<br />

just good marketing—best foot forward and<br />

all that. We do this in the honest hope that<br />

you find that one piece you are looking for,<br />

even if you don’t know what it is yet. We hope<br />

that a few things may pleasantly surprise you,<br />

and make you look twice. And we understand<br />

that some of our work may not quite jive with<br />

your expectations or preferences, but we trust<br />

that you will let us know and tell us why.<br />

I suppose the difference here (aside from<br />

the most obvious differences between a kiln<br />

and a magazine) is that you’ve signed up for<br />

ten firings a year—so we will continue to test<br />

and tweak, like any good clay geek, adjusting<br />

and improving in small ways as we go. Heck,<br />

10 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

we even take the occasional commission, so<br />

let us know if you are looking for something<br />

specific. My email is right up there at the top<br />

of the page, just a click away.<br />

And for those of you who will look<br />

at what we are doing with an eye toward<br />

submitting content, our writing and photo-<br />

graphic guidelines have been updated, and<br />

we welcome ideas and pitches for articles,<br />

departments, topics, tips, glazes, exhibitions,<br />

artists, trends, or just interesting events and<br />

people that affect the culture of clay. Just go<br />

to www.ceramicsmonthly.org and click on the<br />

“Submit Content” link.<br />

As I’ve said before, and as you may have<br />

noticed from the volume number on the contents<br />

page, this is the 59th continuous year<br />

<strong>Ceramic</strong>s Monthly has been in publication,<br />

and that is a lot of history and legacy that, if<br />

not respected, can push against a relaunch like<br />

this. So part of our process was to look back<br />

through the archives and track our history<br />

to make sure that, as we move forward into<br />

what CM will become, we respect and value<br />

the reasons we are where we are. And at the<br />

end of the day, those reasons all come down<br />

to you—I mean us—I mean people working<br />

in clay. I was a reader of CM long before I<br />

ever worked here. I think I may even have<br />

been a reader of CM before I worked in clay,<br />

When redesigning the content, as well as the look and feel, for the new <strong>Ceramic</strong>s Monthly, we made sure<br />

to keep the history and legacy of the publication in mind—all the way back to the first issue in 1953.<br />

Turns out, people have been smart about clay for a long time!<br />

thanks to my high school art teacher having<br />

it around the classroom. So, of course I think<br />

we have arrived at a wonderful combination<br />

of what has always been good about CM and<br />

what it can be moving forward, but I’ll say<br />

again that this will only be true if you play<br />

your part in this dialog. Those of us here on<br />

staff have begun the process—we’ve laid out<br />

the results from the first firing—and we now<br />

await our critique.

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 11

letters<br />

email editorial@ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

New Format and Changes<br />

I am looking forward to the new format.<br />

So far, you’re doing a great job with all the<br />

changes. I was one of those potters who used<br />

to just look at the pictures and did very little<br />

reading. Lately, I have been trying to read<br />

the entire magazine. Just having your picture<br />

on the editor’s page makes me feel like you’re<br />

talking directly to me, your reader. The flow<br />

of information from Internet to magazine has<br />

me feeling like I am totally connected to the<br />

ceramic information age. Good to have young<br />

people with such commitment to expanding<br />

our knowledge of ceramics.<br />

Fujie Robesky, Fresno, California<br />

Submerging<br />

I’ve been doing pottery as a hobbyist for about<br />

40 years. Professionally, I was an oncologist,<br />

and I came to pottery after treating a cancer<br />

patient who was a potter. I’ve always grown<br />

lots of potted plants and he faithfully brought<br />

me pots for my plants. After he was in remission,<br />

he said he had something for me in his<br />

truck. I pictured another beautiful pot, but<br />

what he showed me was a potter’s wheel. He<br />

said, “Doc, I’m tired of making pots for you;<br />

now you can make your own damned pots.”<br />

I have always enjoyed your magazine, and<br />

as I sat reviewing CMs from the past year, specifically<br />

the May issue and the Emerging Artist<br />

feature, I could not help but wonder how many<br />

“submerging” hobbyists are out there who have<br />

really nice work that might be presented in<br />

your magazine. Keep up the fine work.<br />

Thomas Sawyer, Orlando, Florida<br />

Variation, Please<br />

I think the Studio Visits are great. It gives the<br />

artist a chance to be published, but I think<br />

that the information should include more<br />

about technique and less about where they<br />

sell. Where they sell is always just about the<br />

same. There should be some interesting tips,<br />

like how they came to do this work, something<br />

that changed and called to them about<br />

their direction, special moments of discovery<br />

about technique. This should all go in the<br />

12 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

Mind section. I feel that the analysis should<br />

refer to the handmade work. It is great to see<br />

the work, but there should be some variation.<br />

Rebecca Fraser, Santa Barbara, California<br />

A Big Picture<br />

Reading January’s Comment “The Poetics of<br />

Analysis: Why It Is Important to Speak and<br />

Write About Your Work,” by Stanton Hunter,<br />

made me think of how tied we are to our 21st<br />

century culture and economy. When I was a<br />

student, my pottery teacher advised me to<br />

exaggerate some feature of my work—lid,<br />

knob, handle, curve—to set my work apart.<br />

He made it clear this was for creative effect,<br />

not usefulness. I consider now that his expectations<br />

may have been exceeded.<br />

We live in an era of unprecedented change,<br />

which we have an uncommon confidence in as<br />

progress. We consider ourselves better, stronger,<br />

more prosperous, and freer than those who<br />

have preceded us (and perhaps we are), but I<br />

am not convinced that we live better lives or<br />

see ourselves in the context of our surroundings<br />

any better than did previous generations.<br />

It seems our culture has forgotten that<br />

rules and boundaries exist, and that they exist<br />

outside the sphere of our interpretation,<br />

spin, and often our learning. Just because our<br />

work receives recognition or excellent reviews<br />

does not mean that the work itself is good or<br />

lasting. Perhaps it is only human nature that<br />

compels us to want to be thought of as rare,<br />

though rarely are we.<br />

One of the salient features of our culture is<br />

the ease with which we discredit and abandon<br />

tradition. But we Americans don’t have much<br />

of a tradition in clay to abandon. Our folk<br />

pottery tradition was relatively short lived<br />

compared to the Asian traditions cultivated<br />

over centuries. What we have abandoned are<br />

any traditions, Asian or Western. Old pots<br />

and old ways of working with clay stand<br />

against our conventional wisdom because<br />

they are impracticable. And so they are.<br />

The problem is that the great pots and<br />

great works in clay exist outside the bounds<br />

of our culture, its priorities, and our ways of<br />

working and living. They may come from<br />

cultures alien to ours, but the hard fact is they<br />

exist and endure not because of their antique<br />

value but because of their power to move and<br />

shape us. They continue to have a power to<br />

change our lives, and it is that kind of power<br />

I don’t see in much of the work produced<br />

by our high-speed petro culture. If what I<br />

am saying is true, then the question we have<br />

failed to ask ourselves is what constitutes this<br />

enduring power, where does it come from,<br />

and how do we acquire it?<br />

There are two things of which I am dead<br />

certain: that most of what is produced by potters<br />

and artists today is an accurate reflection<br />

of current culture and economy; and that,<br />

were the economy to change, our culture<br />

would change and our work would reflect that<br />

change. Consider that we are free, fed, and<br />

mobile in ways that no other generation could<br />

have imagined, and those external forces have<br />

shaped us and our work. Attendant with this<br />

wealth and leisure is the ability to make, own,<br />

use, and appreciate work that is significantly<br />

removed from our predecessors’ understanding<br />

of beauty or functionality. It is important<br />

to remember that this too shall pass, and that<br />

we and our work will soon enough be artifacts<br />

and antiques. That does not mean that what<br />

we do is unimportant, but an accurate sense<br />

of proportion tends to curb an exaggerated<br />

sense of self worth.<br />

If I am advocating for anything it is simply<br />

rest, a bit of peaceful introspection, and<br />

perhaps restraint. If I am advocating against<br />

anything it is the rigid lock step of a culture<br />

that may well be running out of gas.<br />

Ron Newsome, Wadley, Alabama<br />

Corrections<br />

On page 55 of the December issue, we listed<br />

Jill Rowan’s Resist, Exist, Force as 9 inches in<br />

height, when it is actually 9 feet in height.<br />

On page 59 of the January issue, we<br />

published an incorrect website for Andrew<br />

Martin. The correct web address is<br />

www.martinporcelain.com.<br />

Sincere apologies for the mistakes.—Eds.

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 13

techno fIle<br />

all about iron by John Britt<br />

Iron is everywhere in many different forms, but that doesnÕ t mean it has to be boringÑ or even brown.<br />

Defining the Terms<br />

Iron—The fourth most common element in the earth’s crust and the<br />

most common element (in terms of mass) on the planet, comprising<br />

35% of the earth’s core.<br />

Melting Point: 2795°F (1535°C )<br />

Toxicity: Non-toxic<br />

Forms of Iron<br />

Iron oxide is the most common colorant in ceramics. It is so ubiquitous<br />

that it is very difficult to find a material without some iron—it’s found<br />

in almost everything from feldspars to kaolin to ball clays, earthenware<br />

clays, and many colorants. In fact, many materials require expensive<br />

processing to reduce the amount of iron to acceptable levels.<br />

Iron is a very active metal that combines easily with oxygen. That<br />

means it is very sensitive to oxidation and reduction atmospheres,<br />

producing a wide range of glaze colors and effects from off white,<br />

light blue, blue, blue-green, green, olive, amber, yellow, brown,<br />

russet, tea-dust, black, iron saturate, iron spangles, iron crystalline<br />

(goldstone/tiger’s eye), oil spot, hare’s fur, kaki (orange), leopard<br />

spotted kaki, tan, black seto, pigskin tenmoku, shino, gray (Hidashi),<br />

iridescent, silver, gold, etc. Iron also plays a major role in clay bodies,<br />

slips, terra sigillata, and flashing slips.<br />

There are three major forms of iron used in ceramics: red iron oxide<br />

(Fe203), black iron oxide (FeO or Fe3O4), and yellow iron oxide (FeO<br />

(OH)). There are different mesh sizes and grades, and each contains<br />

varying degrees of impurities that can make a significant difference<br />

in the results you get.<br />

The most interesting thing about iron is that it can act both as a<br />

refractory and a flux. As red iron oxide, Fe2O3, it is an amphoteric<br />

(refractory/stabilizer) similar in structure to alumina (Al2O3). But if it is<br />

reduced to black iron oxide (FeO) it acts as a flux similar in structure<br />

to calcium oxide (CaO). What this means is that a tenmoku glaze<br />

with 10% red iron oxide will be a stiff black glaze if fired in oxidation<br />

because the iron oxide acts as a refractory. But, if the same glaze is<br />

fired in reduction that 10% Fe2O3 will be reduced to FeO, changing it<br />

to a flux, which will make it a glossy brown/black glaze that may run.<br />

Another interesting property of iron oxide is that if it is fired in<br />

oxidation it will remain Fe2O3 until it reaches approximately 2250°F<br />

(approximately cone 8) where it will then reduce thermally to Fe3O4<br />

on its way to becoming FeO. The complex iron oxide molecule simply<br />

cannot maintain its state at those temperatures. This results in the<br />

release of an oxygen atom that will bubble to the surface of the hot<br />

glaze and pull a bit of iron with it. When it reaches the surface the<br />

oxygen releases the iron as it leaves the glaze, creating spots with<br />

greater concentrations of iron oxide. This is what creates an oil spot<br />

glaze. This reaction can easily be seen through the spy hole of a kiln<br />

or with draw tiles. There is an obvious and unmistakable bubbling.<br />

If heated further, these spots begin to melt and run down the pot,<br />

creating a distinctive “hare’s fur” effect.<br />

Have a technical topic you want explored further in <strong>Techno</strong> <strong>File</strong>?<br />

Send us your ideas at editorial@ceramicsmonthly.org.<br />

14 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

Iron Glazes<br />

It would be impossible to show all iron glazes in this article but<br />

highlighting a few will give you a glimpse of the wide variety.<br />

ron roy BlaCk<br />

Cone 6<br />

Talc. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3%<br />

Whiting ....................... 6<br />

Ferro Frit 3134 ..................26<br />

F-4 Feldspar ....................21<br />

EPK Kaolin .....................17<br />

Silica .........................27<br />

100 %<br />

Add: Cobalt Carbonate ............ 1%<br />

Red Iron Oxide ............... 9%<br />

Fake ash<br />

Cone 6 reduction<br />

Bone Ash .................... 5.0%<br />

Dolomite .................... 24.5<br />

Gerstley Borate ............... 10.0<br />

Lithium Carbonate ............. 2.0<br />

Strontium Carbonate ........... 9.5<br />

Ball Clay ..................... 21.0<br />

Cedar Heights Red Art .......... 28.0<br />

100.0 %<br />

Chinese CraCkle (kuan)<br />

Cone 10 reduction<br />

Custer Feldspar ..................83%<br />

Whiting ....................... 9<br />

Silica ......................... 8<br />

100 %<br />

Add: Zircopax (optional) ........... 10%<br />

Adding small amounts of red iron oxide to<br />

this feldspathic base and firing in reduction<br />

will result in the following:<br />

Blue Celadon: 0.5%–1.0%<br />

Blue–Green: 1–2%<br />

Olive to Amber: 3–4%<br />

Tenmoku: 5–9%<br />

Iron Saturate: 10–20%<br />

ketChup red (Jayne shatz)<br />

Cone 6 oxidation<br />

Gerstly Borate ...................31%<br />

Talc. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14<br />

Custer Feldspar ..................20<br />

EPK Kaolin ..................... 5<br />

Silica .........................30<br />

100 %<br />

Add: Spanish Red Iron Oxide. . . . . . . . 15%<br />

Works best on dark colored stoneware. If used<br />

on a buff clay body, the red is less intense.

Sources of Iron<br />

Form Chemical<br />

name<br />

red iron oxide Fe2O3<br />

ferric iron,<br />

Hematite<br />

Black iron oxide FeO<br />

ferrous<br />

oxide,<br />

wustite<br />

Yellow Iron Oxide FeO (OH)<br />

ferric oxide<br />

hydrate,<br />

Geothite<br />

umber, Burnt<br />

umber<br />

sienna, Burnt<br />

sienna<br />

*Synthetic and Spanish Varieties<br />

Synthetic Red Iron is produced by calcining black iron oxide particles in an<br />

oxidation atmosphere. They are then jet milled, which produces “micronized”<br />

red iron oxide particles that are approximately 325 mesh. This type of red<br />

iron is very heat stable (up to 1832°F (1000°C). This differs from black iron<br />

oxide, which changes color at 365°F (180°C) from black to brown to red as it<br />

oxidizes. The color of red iron oxide changes from light pinkish to red to dark<br />

purplish red as the particle size increases.<br />

Characteristics Most Common use<br />

Most common form of iron and is a finely ground material<br />

that disperses well in glaze slurries, contains 69.9% Fe in<br />

the chemical formula, sold as:<br />

• Natural Red Iron Oxide or Brown 521 (85% purity)<br />

• Spanish Red Iron Oxide* (83–88% purity )<br />

• Synthetic Red Iron Oxide* (High Purity Red Iron or Red<br />

4284) (96–99% purity). Very fine 325 mesh. Sometimes<br />

sold as the brand name Crocus Martis or Iron Precipitate.<br />

Strongest form of iron, containing 72.3% Fe in the<br />

chemical FeO, sold as:<br />

• Natural Black Iron Oxide (85–95% purity) 100 mesh; is<br />

black in color and has a larger particle size. In glazes it’s<br />

prone to speckling but is easily eliminated by ball milling.<br />

• Synthetic Black Iron Oxide* (99% purity) 325 mesh<br />

Weakest form of iron, containing 62.9% Fe in the chemical<br />

formula, has a high LOI of 12%, sold as:<br />

• Synthetic Iron Oxide* (96% purity) 325 mesh<br />

• Yellow Ochre or Natural Yellow Iron Oxide (35% purity)<br />

contains impurities of calcium carbonate, silica, and<br />

sometimes manganese dioxide<br />

Calcined Umber which is a high-iron ochre material<br />

containing manganese<br />

Calcined Sienna, which is a high-iron ochre material with<br />

less manganese than umber<br />

iron Chromate Cr2FeO4 Contains chrome and iron oxide (ferric chromate); toxic—<br />

absorption, inhalation, and ingestion<br />

Ferric Chloride/<br />

iron Chloride<br />

iron sulfate<br />

(Copperas)<br />

FeCl3 Water soluble metal salt; toxic—corrosive/caustic, affects<br />

liver, inhalation and ingestion<br />

FeSO4 Water soluble metal salt, soluble form of iron, (aka<br />

Crocus Martis)<br />

Used in glazes, washes, slips, engobes, terra sigillatas,<br />

and clay bodies, used to make celadons, tenmoku,<br />

kaki, iron saturates, etc. (more listed in the text on<br />

page 14)<br />

Normally used from 1–30% in glazes.<br />

Used in glazes, washes, slips, engobes, and terra<br />

sigillatas; used to make celadons, tenmoku, kaki, iron<br />

saturates, etc.<br />

Used in glazes, washes, slips, engobes, terra sigillatas,<br />

and clay bodies; used to make celadons, temmoku,<br />

kaki, iron saturates, etc.; sometimes yellow ochre is<br />

added to porcelain to make “dirty” porcelain (5–9%)<br />

Used in glazes, washes, slips, engobes, terra sigillatas<br />

or claybodies to make a range of reddish-brown<br />

colors; darker than sienna and ochre (yellow iron)<br />

Used to make browns in glazes, washes, slips,<br />

engobes, terra sigillatas or clay bodies<br />

Used to make dark colors in glazes, slips, engobes or<br />

clay bodies; can give gray, brown, and black; can give<br />

pink halos over tin white glazes<br />

Used in low-fire techniques, like pit firing, aluminum<br />

foil saggars, horse hair and raku techniques; also<br />

used in water coloring on porcelain techniques<br />

Salt used in water coloring on porcelain, raku, and<br />

low-fire soda<br />

iron phosphate FePO4 Rarely used but can be used to develop iron red<br />

colors; sometimes used instead of bone ash as a<br />

source of phosphate without the calcium in synthetic<br />

bone ash (TCP or tri-calcium phosphate)<br />

rutile (light, dark,<br />

and granular)<br />

illmenite (powdered<br />

and granular)<br />

TiO2 Most common natural ore of titanium, containing various<br />

impurities including iron ( up to 15%)<br />

FeTiO3 Naturally occurring ore containing iron and titanium, higher<br />

in iron than rutile (when 25% or more iron is present)<br />

iron Clays e.g., Redart, Albany slip, Alberta Slip, Barnard Slip (aka<br />

Blackbird Slip), Michigan slip, Lizella, laterite, and other<br />

assorted earthenware clays<br />

Magnetic iron<br />

oxide<br />

Fe3O4<br />

Magnetite<br />

Iron scale or iron spangles—coarse, hard particles that<br />

resist melting and chemical breakdown<br />

Used in glazes, washes, slips, engobes, and terra<br />

sigillatas to give yellows, tans, greens, blues, and<br />

milky, streaky, mottled textures; also used to produce<br />

crystalline glaze effects<br />

Commonly used to produce speckles in glazes or<br />

clay bodies<br />

Used in glazes, slip glazes, slips, engobes, terra<br />

sigillatas, and claybodies to make a range of reddishbrown<br />

colors<br />

Gives speckles in clay bodies and glazes<br />

Spanish red iron oxide is bacterially ingested iron oxide that is micronized.<br />

The Tierga mines in Spain found that their iron sulfide was inadequate for<br />

steel making (which accounts for 95% of the iron market). After some time<br />

a worker noticed that the iron in a pool of rain water turned a brighter shade<br />

of red after it was heated. This turned out to be caused by a bacterium, that<br />

uses iron sulfide as an energy source. The bacterium changes the state of the<br />

iron, which is then put into evaporative ponds where it forms green crystals.<br />

These are then roasted to produce Spanish red iron oxide.<br />

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 15

tIps and tools<br />

rolling reclaim by<br />

space is a valuable resource to most ceramic artists and that includes potters with a tiny space tucked in<br />

the basement, students with a single table and chair in a classroom, and community art centers like the<br />

one shown here. Reclaiming clay can take over these small spacesÑ but this can help.<br />

Utilize the space underneath your tables with a rolling<br />

reclaim table. The top surface of the table is made of a<br />

fiber cement backerboard typically used for tile installations,<br />

which is available at home stores. We use this for all our<br />

tables because it absorbs water, doesn’t warp, and can be<br />

scraped clean over and over with no damage to the surface.<br />

Make a simple frame with a few braces in between to<br />

support the weight of the heavy backerboard and clay, top<br />

with plywood then the cement board. When measuring for<br />

the frame, remember that it needs to fit easily between the<br />

legs of the table above plus allow some extra room for the<br />

casters to roll it into place. Use large casters as the table<br />

with wet clay will be quite heavy. Put sturdy drawer pull<br />

handles on the front to make it easy to pull the table out<br />

and push it back into place. The rolling table also doubles<br />

as a great work surface.<br />

Send your tip and tool ideas, along with plenty of images, to<br />

editorial@ceramicsmonthly.org. If we use your idea, you’ll<br />

receive a complimentary one-year subscription to CM!<br />

16 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

Donna Jones

A Revolutionary Design!<br />

Call for details.<br />

www.baileypottery.com<br />

Bailey Pottery Equip. Corp. PO Box 1577 Kingston NY 12401<br />

www.BaileyPottery.com TOLL FREE (800) 431-6067<br />

Direct: (845) 339-3721 Fax: (845) 339-5530<br />

Bailey “Advanced Logic”<br />

Gas Fired Reduction<br />

Kilns<br />

Bailey has reinvented the automated<br />

reduction process and developed the<br />

most logical, easy-to-use, totally<br />

automated gas fired kiln.<br />

Bailey has designed a new revolutionary<br />

controller for easy-to-use programmable<br />

operation.<br />

This new generation of Bailey<br />

ENERGY SAVER gas kilns produces<br />

consistently reliable & beautiful<br />

reduction or oxidation firings. It can<br />

be manually fired or program fired,<br />

and it even allows delayed starts so<br />

your kiln is at body reduction first thing<br />

in the morning!<br />

Look what you get!<br />

Manual or Program Firing Oxygen Readouts<br />

20 Segments per program 12 Stored Programs<br />

Delayed Start Function Real Time Clock<br />

Multiple Stage Air and Gas Forced Air Uniformity<br />

Set Point or Timed Segment Priority<br />

Automated Damper with decimal entry system<br />

Unlimited Tech Support and Free Training Courses<br />

And there’s much more...<br />

C US<br />

Certified for the<br />

US and Canada.<br />

Professionals Know<br />

the Difference.<br />

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 17

exposure<br />

for complete calendar listings<br />

see www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

1 Persian Jar, 14 in. (36 cm) in height, salt<br />

glazed, 2002. 2 Flattened bottle, 6 in. (15 cm)<br />

in height, reduction fired, 1977. 3 Two round<br />

cups, seedpod motif and fish motif, each<br />

4 in. (10 cm) in height, 1992. All works by<br />

Michael Simon. “Michael Simon” at Northern<br />

Clay Center (www.northernclaycenter.org), in<br />

Minneapolis, Minnesota, March 12–May 1.<br />

18 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

1<br />

3<br />

2

1<br />

4<br />

1 Wayne Branum’s covered jar,<br />

9 in. (23 cm) in height, cone 1 red<br />

clay, white slip with Newman red terra<br />

sigillata, electric fired, 2010. 2 Mark<br />

Pharis’ stacked plates, earthenware,<br />

2010. 3 Sandy Simon’s cream and<br />

sugar, each 3½ in. (9 cm) in diameter,<br />

nichrome wire, clear glaze, porcelain,<br />

reed, “lucky” seed from the Amazon,<br />

2010. 4 Randy Johnston’s tray, 17½ in.<br />

(44.5 cm) in length, stoneware, black<br />

and white slip trailing, wood fired,<br />

2010. “Classmates” at Northern Clay<br />

Center (www.northernclaycenter.org), in<br />

Minneapolis, Minnesota, March 12–May 1.<br />

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 19<br />

2<br />

3

exposure<br />

Left: Steven Godfrey’s Talking<br />

Cardinal Urn, 9 in. (23 cm) in<br />

height, porcelain, glaze, 2010.<br />

Right: Andy Shaw’s place<br />

setting, largest plate is 12<br />

in. (30 cm) in diameter,<br />

porcelain, glaze, 2010.<br />

“Steven Godfrey and Andy<br />

Shaw,” at Santa Fe Clay<br />

(www.santafeclay.com), in<br />

Santa Fe, New Mexico,<br />

March 4–April 9.<br />

20 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

1 Valerie Zimany’s Mori Mori<br />

Tenko Mori (detail), 5 ft.<br />

(1.5 m) in length installed,<br />

wheel-thrown and slip-cast<br />

porcelain, glazes, 2009. 2<br />

Peter Morgan’s Voracious<br />

Wombat, 8 ft. (2.4 m) in<br />

length installed, ceramic<br />

and mixed media, 2009. 3<br />

Blake Williams’ Four Hundred<br />

Square Inches of Orange,<br />

15 ft. 1 in. (4.6 m) in length<br />

installed, porcelain slip-cast<br />

doe skulls, reflective tape,<br />

reflective tacks, 2008. 4 Haejung<br />

Lee’s Hope, 9 ft. (2.7<br />

m) in height, cast porcelain<br />

and mixed media, 2009.<br />

5 Daniel Bare’s Re/Claim;<br />

Cascade, 18 in. (46 cm) in<br />

height, post-consumer found<br />

objects, porcelain, glaze,<br />

2010. “Method: Multiple”<br />

at C. Emerson Fine <strong>Arts</strong><br />

(www.c-emersonfinearts.com),<br />

in St. Petersburg, Florida,<br />

March 29–April 2.

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 21

exposure<br />

1 Ayano Ohmi’s Gate II, side view 52½ in. (1.3 m), earthenware, iron oxide,<br />

2010. “Ayano Ohmi Sculpture” at Ceres Gallery (www.ceresgallery.org) in<br />

New York, New York, March 1–March 26. 2 Derek Weisberg’s Ghosts Waltz<br />

Behind Our Backs, 26 in. (66 cm) in height, ceramic, 2010. Photo: Ira Schrank.<br />

“Auroral Dreaming” at Anno Domini Gallery (www.galleryad.com), in San Jose,<br />

California, through March 19. 3 H.P. Bloomer’s bowl, 10 in. (25 cm) in length,<br />

porcelain, soda-fired, 2010. 4 Chandra DeBuse’s Berry Bowl with Golden<br />

Spoon, 8 in. (20 cm) in length, porcelaneous stoneware, luster, 2010. 5<br />

Ross Hilgers’ Iron Basin, 22 in. (56 cm) in height, clay, 2010. “Beyond the<br />

Brickyard Exhibition” at the Archie Bray Foundation for the <strong>Ceramic</strong> <strong>Arts</strong><br />

(www.archiebray.org) in Helena, Montana through April 2.<br />

22 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

1<br />

2<br />

4<br />

3<br />

5

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 23

exposure<br />

1 Tyler Lotz’s A Cold Ideal, 3 ft. 9 in. (1 m) in length installed, ceramic, acrylic,<br />

foam, steel, hardware, and epoxy, 2010. “Future Vestiges” at Elmhurst Art<br />

Museum (www.elmhurstartmuseum.org), in Elmhurst, Illinois through March 20.<br />

2 Pete Pinnell’s teapot, 8 in. (20 cm) in length, wheel-thrown and altered sodafired<br />

porcelain, brass handle. “<strong>Ceramic</strong>s Visiting Artist Exhibition: Pete Pinnell”<br />

at Workhouse <strong>Arts</strong> Center (www.workhousearts.org), in Lorton, Virginia through<br />

March 27. 3 Suzuki Goro’s Patchwork Teabowl with Gold Inlay, 5½ in. (14 cm)<br />

in length, stoneware, 2010. 4 Shiro Tsujimura’s Kuro Hikidashi Chawan, 4½<br />

in. (11 cm) in length, stoneware, 2010. 5 Koichiro Isezaki’s Green Chawan,<br />

5½ in. (14 cm) in length, stoneware with black slip, hikidashi (removed from<br />

kiln at peak temperature of 2282°F (1250°C)), 2010. “The Elusive Teabowl”<br />

at Lacoste Gallery (www.lacostegallery.com) in Concord, Massachusetts<br />

March 12–April 3. 6 Johannes Nagel’s Archetypes, 6 in. (15 cm) in length, cast<br />

and assembled porcelain, cobalt, gold, fired to 2282°F (1250°C) in oxidation<br />

2010. “Improvisorium” at Kunstforum Solothurn, (www.kunstforum.cc) in<br />

Solothurn, Switzerland through March 27.<br />

24 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

1<br />

6<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 25

clay culture<br />

one hundred jars<br />

In the November 2009 issue of CM, as well as on the cover, we<br />

included the work of Daniel Johnston. At the time, he was mid-way<br />

through a very ambitious project to make 100 large jars in his woodburning<br />

kiln in Seagrove, North Carolina. In October of 2010, the<br />

project came to fruition after five firings in his 90-cubic-foot kiln<br />

transformed 11,000 pounds of local clay, 25 gallons of glaze and<br />

slip, 30 cords of scrap wood, and 800 pounds of salt into 100 large<br />

glazed jars. The pots were numbered in the order of production from<br />

001 through 100. This numbering system allowed a clear tracking of<br />

the artistic evolution, demonstrating an exploration of form through<br />

extended production.<br />

This project, like many of its kind, percolated for a long time<br />

before it actually became reality, and was an amalgamation of ideas<br />

that sprouted from a wide sampling of Johnston’s artistic experiences.<br />

It was largely derived from Johnston’s experience living in Northeast<br />

26 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

All 100 jars sold in 17 minutes, and<br />

Johnston took orders for an additional 70.<br />

1 The line of jars stretched down the road to<br />

the pottery, and each customer was allowed<br />

in, one at at ime, to select the jar they wanted.<br />

2 This is the last kiln load of the five firings it<br />

took to make all 100 jars. 3 All 100 jars were<br />

set out in the yard prior to being moved to the<br />

road for their “lineup.”

1<br />

3<br />

Thailand in the village of Phon Bok, where he worked with Thai<br />

potters producing big jars on a large scale, but as we all know, making<br />

is one thing and selling is another. The jar project was intended<br />

to show how large pots can be produced in North Carolina using<br />

the South East Asian model. In this way, Johnston created a bit<br />

of a social experiment as well as an artistic and physical challenge.<br />

Would the pottery-buying public, even in a place with as rich a<br />

ceramic history as North Carolina, support pots that spring from<br />

a function that is rooted in a different culture (the water jars of<br />

Thailand)? The short answer: Yes. At 11am on October 22, 2010,<br />

all 100 jars sold in 17 minutes, and Johnston took orders for an<br />

additional 70 large jars. Here’s to more of the same, Daniel!<br />

To see more images of the project from start to finish, and to learn<br />

more about Daniel Johnston, go to www.danieljohnstonpottery.com.<br />

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 27<br />

2

clay culture<br />

low high-tech by<br />

28 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

Peter Wray<br />

<strong>Ceramic</strong> Tech Today (www.ceramics.org/ceramictechtoday) brings us this intersection of art, sound, and science.<br />

I sense a trend emerging. Lately we’ve seen a growing number of ceramic speakers that<br />

evoke the Nipper side of the old RCA logo. Now its a pleasure to present a speaker<br />

that represents the other half.<br />

Science + Son (www.scienceandsons.com) has developed three generations<br />

of the Phonophone passive amplification speakers. Their<br />

website states that, “Through passive amplification alone, these<br />

unique pieces instantly transform any personal music player<br />

and earbuds into a sculptural audio console.<br />

“Without the use of external power or batteries, the<br />

Phonofone inventively exploits the virtues of horn<br />

acoustics to boost the audio output of standard<br />

earphones to up to 55 decibels (or roughly the<br />

maximum volume of laptop speakers).<br />

“Upon connecting active earphones to the<br />

Phonofone their trebly buzzing is instantly<br />

and profoundly transformed into a warm,<br />

rich, and resonant sound.<br />

“The Phonofone is constructed entirely<br />

from ceramic. Not only environmentally<br />

low impact, ceramics are inherently rigid<br />

and resonant, lending themselves well to<br />

this application.”<br />

The Phononphone II will<br />

work with just about any<br />

MP3 player. It stands<br />

20 in. (51 cm) in height,<br />

and sells for $600. The<br />

diagram to the right<br />

shows a little more<br />

about what’s going<br />

on acoustically.

The Florida Holocaust Museum Welcomes<br />

While attending the conference please visit<br />

Peace/War, Survival/Extinction:<br />

An Artist’s Plea for Sanity<br />

On view March 11, 2011 – May 30, 2011<br />

Artwork by ceramic sculptor Richard Notkin including<br />

finely-crafted teapots, a tile-mural, an installation and<br />

other objects.<br />

Symbol-rich sculptures provide a social commentary<br />

on the human condition, war, and man’s inhumanity to<br />

man while embracing a strong visual aesthetic.<br />

Open <strong>Daily</strong> - 10 am to 5 pm<br />

September 1st through May 31st - Thursday evenings until 8 pm<br />

Last admission is an hour and a half before closing<br />

55 Fifth Street South | St. Petersburg, Florida 33701 | 727.820.0100<br />

www.flholocaustmuseum.org<br />

Richard Notkin; “Heart Teapot: Hostage/Metamorphosis IV”<br />

Yixing Series (alternate view) 2006Stoneware, luster, 7” x 12 1/4” x 6”<br />

Media Sponsor:<br />

Proud Partner:<br />

Work by:<br />

Brendan Tang<br />

<strong>Ceramic</strong> Residencies and Workshops<br />

in CANADA’s newest studios.<br />

Application Deadline: April 15, 2011<br />

medalta.org/miair<br />

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 29

clay culture<br />

pots in action<br />

Making a living from your work not only takes tremendous skill but these days it demands some fairly<br />

creative marketing as well. ayumi Horie has done just that by bridging the typical website pot shot with<br />

the casual, off-the-cuff action shot seen on blogs or social networking sites. the result is both humorous<br />

and smart, not to mention a tour around globe looking at great pots.<br />

“Pots in Action began five years ago as a crowd-sourcing<br />

project designed to document where my handmade pots<br />

went after the studio and how people really use them,”<br />

says Horie. “I was tired of seeing pottery on neutral<br />

graded backgrounds; I wanted to see them sloppy with<br />

sauce or balanced on a car dashboard or in a dirty sink.<br />

The earliest pictures were strictly candid, but over time<br />

they shifted to more creative and orchestrated scenes<br />

where some people even took pots with them on vacations<br />

abroad. With the invention of Google maps, it got<br />

even better. I could plot pictures and users could then<br />

zoom in and out of cities, states, and countries, pinpointing<br />

geographically where a photographic moment in time<br />

occurred. The interactivity of Google Maps made the<br />

outreach of handmade pots feel even broader, because<br />

suddenly we could all identify the regional flavor of each<br />

image, on top of all its idiosyncrasies. Last summer, an<br />

online photo contest garnered more images for the community<br />

project and helped underscore how relevant and<br />

important handmade pots are to many people around<br />

the world.”<br />

Top: Interactive Google Map from Ayumi Horie’s Pots In<br />

Action series. To see all the images and to explore the map,<br />

go to www.ayumihorie.com.<br />

1 Christina Smeltz, Florida. 2 Collin Moses, Indiana.<br />

3 Jill Ward, British Columbia. 4 Steve Sharafian, California.<br />

5 Yulia Nikitina, Moscow.<br />

30 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5

coda ad12111_Layout 1 1/31/11 10:25 PM Page 1<br />

CRAFT ORGANIZATION DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION PRESENTS<br />

2011 CODA LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE<br />

June 8-11, 2011 • Portland, Maine<br />

Connecting the Dots<br />

COLLABORATING...FUNDRAISING...TELLING YOUR STORY...<br />

Learn and network<br />

Hear from nationally recognized speakers, learn best<br />

practices, improve your organization's story and network<br />

with colleagues. Don't miss this opportunity for<br />

professional development and Maine lobster dinners!<br />

870.746.5159 • www.codacraft.org<br />

Hosted by The Maine Crafts Association<br />

Sponsors: Maine <strong>Arts</strong> Commission; Maine Dept. of Economic and Community<br />

Development ; Maine Office of Tourism; Maine Community Development Association;<br />

Handmade ® at the New York International Gift Fair ®; Saint Joseph's University;<br />

American Craft Council; The Crafts Report<br />

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 31

clay culture<br />

periodic table of videos<br />

The Periodoc Table of Videos is a project<br />

developed by the University of Nottingham<br />

in England. Several chemists host the videos,<br />

which look at each element on the periodic<br />

table, and discuss their various properties as<br />

they relate to everyday life, or life in the lab.<br />

Of particular interest to a ceramics audience<br />

are the videos featuring common elements<br />

that are also near and dear to our studios.<br />

From shells to stalactites to the White<br />

Cliffs of Dover, the video on calcium (Ca),<br />

one of the most common non-gaseous elements<br />

on earth, shows various examples of<br />

calcium carbonate (whiting). Professor Martyn Poliakoff, research<br />

professor of chemistry (that’s him at the top of the page), explains<br />

that calcium compounds are white because they have no free electrons<br />

to move between different energy levels, which is what produces<br />

the colors we see. Tiny crystals in the compounds scatter the<br />

light, making them appear white. When burned, however, calcium<br />

compounds produces a red flame.<br />

Magnesium (Mg) is the lightest, most easily used alkaline earth<br />

metal. We use magnesium carbonate as a flux in high-temperature<br />

glazes, and as a refractory or opacifier in low-temperature glazes.<br />

The fact that it is one of the lightest elements on the periodic table<br />

explains why it is so light and fluffy, and why a 50-pound bag of the<br />

stuff is so much larger than a 50-pound bag of other materials. When<br />

heated by Dr. Pete Licence, who does most of the more explosive<br />

demonstrations in the videos, it combusts and gives off a brilliant<br />

white light as it burns. This property made it useful as a component<br />

in some of the early flash bulbs for film cameras.<br />

Silicon (Si) which we use in the form of silica (silicon dioxide or<br />

SiO2) is most commonly found on earth as sand or in quartz. Prof.<br />

Poliakoff shows off a silicon wafer of single crystal silicon 20 cm in<br />

diameter with computer microchips built up or “grown” on top by<br />

32 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

layering different materials. Silicon is used because it<br />

is a semiconductor. After the chips are created, they’re<br />

cut from the wafer, and then tested before being used.<br />

Boron (B) is a metalloid, and has some properties of<br />

metal, and some properties of a non-metal. It’s commonly<br />

used in households. That box of 20 Mule Team Borax<br />

or Persil Laundry Detergent booster is a compound of<br />

perborate and silicate that when placed in 60°C water,<br />

forms hydrogen peroxide, which bleaches clothes. The<br />

experiment done by Dr. Debbie Kays shows that there’s<br />

an organic boron compound that, when burned, gives<br />

off a similar (though smaller) green flame to pentaborane,<br />

nicknamed the the green dragon, which was investigated<br />

in the ’50s as a rocket fuel.<br />

Zinc (Zn) is an abundant<br />

soft metal. We use<br />

it in oxide form as an<br />

auxiliary flux, but zinc is<br />

also found in high quality<br />

roofing material because<br />

it is slow to oxidize. Zinc<br />

is also essential to life in<br />

many ways. In fact, if you<br />

don’t have enough zinc in<br />

your body, you can’t smell<br />

things. Oh, and the chemists<br />

can’t help but show us<br />

that when it’s combined with certain other elements and set alight,<br />

it makes a fantastic show of popping, arcing sparks.<br />

Iron (Fe)—some of us in the ceramics world love it, some of<br />

us not so much, at least when it comes to having iron oxide in our<br />

otherwise perfectly white clay body.<br />

The chemists do an experiment involving iron to show what is<br />

called a thermite reaction (an oxidation/reduction reaction between<br />

a metallic oxide and a pure metal that produces an extreme amount<br />

of heat). They’re conducting the experiment outside, usually a clue<br />

that they anticipate a big bang or fire. Using iron oxide powder as the<br />

oxidizer, aluminum powder as the reducing agent, and a flowerpot<br />

on a stand as the crucible, Dr. Licence lights the heat source—a<br />

sparkler—and sets off the reaction shown in the image above. The<br />

result is the violent reduction of the iron oxide, with the aluminum<br />

metal stealing the oxygen to form aluminum oxide. The reaction is<br />

so hot that the side of the pot explodes off, and the iron melts into<br />

a molten mass of pure metal.<br />

To see the strength and power of a thermite reaction as elements<br />

fight for oxygen, or the sparks, fires, and mini explosions created during<br />

many experiments demonstrated, visit www.periodicvideos.com<br />

and click on each element’s symbol on the chart to watch the videos.

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 33

studio visit<br />

Lorna Meaden<br />

durango, Colorado<br />

Just the Facts<br />

Clay<br />

porcelain<br />

Primary forming method<br />

throwing on the wheel<br />

Primary firing temperature<br />

cone 10 reduction soda<br />

Favorite surface treatment<br />

slip inlay<br />

Favorite tools<br />

my newly built soda kiln<br />

34 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

Studio<br />

I have a new (finished just a year ago) studio that is 650 square feet, located on the property<br />

where I live. No matter how big it seemed when it was first built, it always seems like it<br />

could be bigger.<br />

After finishing graduate school in June of 2005, I spent three years doing residencies and<br />

teaching short-term adjunct positions. While back in Durango for a visit, unsure whether<br />

I would stay or not, an opportunity to buy a piece of property from a friend fell in my lap.<br />

While initially intimidated by what seemed apparently impossible, over several months and<br />

many long conversations with friends and family, I came up with a plan to “make it work,”<br />

and dove in.<br />

The property, where I have now lived for two and a half years, is three in-town lots with<br />

two small houses that were in need of a lot of work. With the help of my family, I got the<br />

larger of the two houses in rental condition, and the smaller house converted into a temporary<br />

combination of studio and living space. Over the following year, my brother and his<br />

friend built my new studio building that my father designed. After living and working in a<br />

450-square-foot space for a year and a half, I happily moved my workspace out of my house<br />

and into the 650-square-foot studio. It’s a two-story, barn-shaped building, and I love the<br />

rounded ceiling and the great view from the upstairs window.

I throw, assemble, and decorate in<br />

the upstairs space, and slip cast and glaze<br />

downstairs. One of the best things about<br />

my property is that I have room to grow.<br />

Years from now, I hope to build a house<br />

that I live in, and then make my little<br />

house where I currently live available for<br />

an apprentice.<br />

Adjacent to the studio building is a<br />

90-square-foot shed for tools, glaze chemicals,<br />

and my electric kiln. In between the two buildings is my new<br />

soda kiln that was built (with the help of generous friends) this past<br />

fall. The design of the kiln is based on the “little vic” kiln at Anderson<br />

Ranch <strong>Arts</strong> Center. It is a small boury-box style cross-draft kiln that<br />

can be fired with wood, natural gas, or oil. The kiln building project<br />

was funded through selling pots, and the small retirement fund I saved<br />

up and cashed in from teaching adjunct for three years.<br />

“The fact that I’m willing<br />

to live in such a small space<br />

helps. After all, doesn’t<br />

everyone dream of a studio<br />

bigger than their house?”<br />

When I finished graduate school<br />

almost six years ago, I never imagined<br />

I would be able to afford, maintain, or<br />

manifest a home and studio of my own,<br />

although that has always been my intention.<br />

Currently, my rental house helps<br />

financially sustain the property. The fact<br />

that I’m willing to live in such a small<br />

space helps. After all, doesn’t everyone<br />

dream of a studio bigger than their house?<br />

People often ask me, “Can you believe it? You are living the dream!”<br />

I do think I am very fortunate. This home and studio have already<br />

brought me so much happiness and stability, and I can only believe<br />

it because I had to work harder than I ever imagined I could in<br />

order to begin to see it materialize. I’ve always liked the saying, “the<br />

harder you work, the luckier you are,” and I have found that to be<br />

true in most things.<br />

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 35

Striped flask, tea set, and muffin<br />

pan, all thrown and altered<br />

porcelain, with inlaid slip, then<br />

glazed and fired to cone 10 in<br />

reduction with soda, by Lorna<br />

Meaden, Durango, Colorado.<br />

Paying Dues (and Bills)<br />

I learned to throw in high school, and went to get a bachelor of arts<br />

degree in art from Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado, and<br />

then a master of fine arts degree in ceramics from Ohio University<br />

in Athens, Ohio.<br />

Though it varies widely, I spend about 40 hours per week in the<br />

studio. I teach one ceramics class, adjunct, at Fort Lewis College,<br />

and I travel to teach quite a few workshops a year.<br />

Mind<br />

The older I get, the more I feel like I need a balance in my life to<br />

be able to be creative. In other words, I am more productive in my<br />

studio if I am also getting enough sunshine, laughing hard with my<br />

friends, traveling outside the small town where I live, and exposing<br />

myself to places and things I’ve never seen before.<br />

36 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

Body<br />

I work out anywhere from three to five days a week. Exercise seems<br />

to be the only thing that wards off the pain of years of repetitive<br />

movement. I currently have no health insurance, but my goal is to<br />

get it within the next year.<br />

Marketing<br />

Currently, all of my work is sold through galleries. My goal is to sell<br />

half of my work through my studio and on my website. The advantages<br />

to gallery sales are the broader market they reach and the sales<br />

knowledge and experience of gallery owners. The disadvantages are<br />

packing and shipping the work and giving up a percentage of sales.<br />

I feel that all the traveling I do to teach workshops has been a<br />

great way to expand the market for my work. In the past, entering<br />

juried shows was a way that new galleries would see my work.

Above: There is nothing, of<br />

course, like building a kiln you<br />

have waited years to build.<br />

Meaden’s friends pitch in to<br />

help with the hard work.<br />

Right: detail of a cocktail<br />

pitcher (likely put into use<br />

directly after the kiln building).<br />

Below: Watering cans in<br />

progress on the second floor of<br />

the studio, where forming and<br />

some decorating take place.<br />

I know that the Internet is a valuable and powerful tool, but I<br />

don’t really like computers, and I especially don’t like spending my<br />

time sitting in front of, or staring at, one. I definitely participate in<br />

online sales, emailing, networking, etc.; however, my philosophy<br />

is that if making good work and keeping it interesting is my first<br />

priority, everything else will follow.<br />

Most Valuable Lesson<br />

Be resourceful and stay out of debt. Also, find a way to have enough<br />

concentrated work time without spending too much time alone.<br />

www.lornameaden.com www.redlodgeclaycenter.com<br />

www.archiebray.org/catalog www.ferringallery.com<br />

www.harveymeadows.com www.theclaystudio.org<br />

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 37

Above: Toshiko Takaezu surrounded by Moon Balls, 1979. Photographer unknown, Toshiko Takaezu<br />

Archives. Opposite: Three Tamarind Forms, to 35 in. (89 cm) in height, glazed stoneware.<br />

38 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org

AN UNSAID<br />

QUAlIty<br />

BY Janet Koplos<br />

Janet Koplos<br />

Toshiko Takaezu is seen as a rather private person, 1 and she is known for workshops that<br />

rely on demonstration more than talk. She is reluctant to analyze her work, and she tends to<br />

speak in bursts of short sentences, as if the words had to pass some filter to be free. She was<br />

delighted when a young viewer said that her work spoke in the language of silence. 2 It may be<br />

that she has inherited the Japanese notion that brevity makes a thing or event more precious,<br />

for it seems that her hard-won words open doors to thinking both about her abstract ceramic<br />

sculptures and life in general. Consequently, “some see her as a kind of priestess of clay, a nun<br />

of earth and fire, a female monk,” the critic John Perreault has observed. 3<br />

Her work and career can be characterized by a number of contrasts or even paradoxes.<br />

A modest example: she is famous for her ceramic work but has remained interested in<br />

weaving and painting as well—mediums that are radically different in dimension and in<br />

process. More significant: her work is recognized for both subtlety and vividness in color<br />

and for both monumentality and intimacy in size. As she has become more reserved in<br />

person, she has made sound a part of many of her works, including bronze bells and closed<br />

ceramic forms that contain a wad of clay that clatters as they are moved. All these oppositions<br />

expand the impact of her work.<br />

Less happy, for the scholar and biographer at least, is the fact that although many qualities<br />

of her work are distinctive and it is immediately recognizable as hers, she has never dated<br />

or conscientiously documented her creations. Thus her works are more easily experienced<br />

individually than studied as a whole.<br />

That may be just fine with<br />

her, but her ceramic oeuvre is<br />

agonizingly amorphous for the<br />

curator or critic who wishes to<br />

track it.<br />

She made modest functional<br />

vessels first, moved<br />

into multi-spouted forms in<br />

the early 1950s, had closed<br />

some forms except for an air<br />

hole by the start of the 1960s,<br />

and then developed Moon pots<br />

(large spheres) as well as Forests<br />

(groups of cylindrical towers),<br />

and increasingly larger closed<br />

forms, some as much as 6 feet<br />

tall. The surprise is how varied<br />

they are despite the signature<br />

www.ceramicsmonthly.org march 2011 39

features by which we think we know her work: multiple necks,<br />

diminutive nipples, globe forms, upright monoliths, and above all,<br />

painterliness in the poured and brushed glazes.<br />

It is widely presumed that Takaezu’s work is influenced by<br />

Japanese art. Yet although she was born to Japanese immigrants<br />

and spoke only that language until she started school, her development<br />

as a young artist was all within the American culture of<br />

Hawai‘i, and she visited Japan for the first time only after she had<br />

left her home state and completed graduate school at the Cranbrook<br />

Academy of Art in Michigan. She said that any influence<br />

came from the culture in general, not specifically from Japanese<br />

ceramics. Still, seeing the importance of clay in Japan had to have<br />

reinforced her inclinations. And one can’t help but associate her<br />

laconic discussion of her work with the Japanese belief that the<br />

most profound things cannot be spoken. But it’s important not<br />

to exoticize her work. She should be recognized as an individual<br />

and original creator, the product of varied influences and her own<br />

distinctive ideas.<br />

Mentors<br />

Takaezu’s earliest work, like that of many students, shows similarities<br />

to the products of the teachers she admired and responded to. Her<br />

first significant teacher in ceramics was Claude Horan at the University<br />

of Hawai‘i at Manoa. His stoneware pots of the late 1940s,<br />

when Takaezu studied with him, are squat, robust, and stable. His<br />

Copper red closed form,<br />

7 in. (18 cm) in height, glazed<br />

porcelain, early 1990s.<br />

40 march 2011 www.ceramicsmonthly.org<br />

wide-ranging oeuvre included, interestingly, both closed forms<br />

and multi-spouted forms.<br />

As she grew serious about ceramics and decided that she needed<br />

to leave the islands to further her skills and knowledge, Takaezu<br />

came across images in a magazine of the work of Maija Grotell,<br />

the Finnish immigrant who had been teaching at the Cranbrook<br />

Academy of Art in Michigan since 1938. Grotell was esteemed for<br />

her mastery of wheel throwing, having arrived in the US at a time<br />

when the skill was uncommon among studio potters. Her forms,<br />

like Horan’s, were in the sturdy-and-resolute camp of the time<br />

(rather than, say, crusty or delicate).<br />

Takaezu’s work in graduate school and immediately thereafter<br />

certainly has similarities to Grotell’s. The fact that Takaezu responded<br />

to an image of Grotell’s work in the first place suggests<br />

that those forms inherently spoke to her, or for her, so that the<br />

similarities should not be ascribed simply to student copying,<br />

which Grotell forbade. 4 It’s likely that the two women simply spoke<br />

in the same formal language, despite their vastly different points of<br />

origin. (Curiously, Grotell may have influenced her in another way:<br />

Takaezu remembers her teacher’s resistance to idle talk and that she<br />

offered criticism only when asked. She says, “Maija didn’t say very<br />

much and what she didn’t say was as important as what she did say,<br />

once you realized that she was thoroughly aware of everything you<br />

did. The realization and acceptance of the rare wordless words in<br />

Maija’s teaching and being had a strong impact . . . .” 5 )<br />

Early Career<br />

Multi-spouted vessels brought Takaezu early awards and attention.<br />

She was making them by 1953. In January 1955, when her work<br />

was first noted in the two-year-old <strong>Ceramic</strong>s Monthly magazine,<br />

what was illustrated was a two-necked free-form bottle. It was<br />

part of a group of works that took the top award in an exhibition<br />

of Wisconsin “designer-craftsmen” (as ceramic artists were called<br />

in those days) at the Milwaukee Art Institute during her one-year<br />

teaching job as a sabbatical replacement at the University of<br />

Wisconsin, Madison.<br />

Multiplicity seems to have been an important part of her<br />

aesthetic then, perhaps not surprising for a middle child in a<br />

family of eleven children—she must have always had others<br />

around her. Moreover, as the progeny of a farming family, she<br />

would have been accustomed to harvests, to masses of things.<br />

And one might also speculate that great numbers would seem<br />

appropriate to a person from a tropical locale like Hawaii,<br />

where vegetation grows lushly, even overwhelmingly. While<br />

the nature of pottery itself leads to multiples, would she have<br />

worked so much with twinning, suggestions of cell division,<br />

or clusters of mouths had she come from a desert region or the<br />

vast open plains of the Midwest?<br />

Another series from this early period, called Tamarind, consists<br />

of three stacked and joined bulbous forms that echo in vastly<br />

greater scale the three-seed pods of the tropical tamarind tree.<br />

The base vessel tends to be slightly larger than those above it, and<br />

the top pot terminates in the small protrusion she calls a nipple,

which became a standard feature in later works. The Tamarind<br />

forms served as complex grounds for painting, featuring both<br />

undulating vertical lines that emphasize the overall elongation<br />

and patches of dark brushwork that emphasize the segmentation.<br />

The colors remain earthy.<br />

Teapot Variations<br />

One backstory of the multi-spouted vessels is that they evolved<br />

from her teapots. 6 She may not have been the first to develop<br />

spouts like this, but the idea took off and became a familiar form<br />

in the 1950s. Another influence on this innovation may have<br />

been the work of Leza McVey, who Takaezu would have known<br />

at Cranbrook and later in Cleveland (at Cranbrook, she studied<br />

sculpture with William McVey, Leza’s husband, and he was teaching<br />