Springboard Unit 1 - Teachers.ocps.net

Springboard Unit 1 - Teachers.ocps.net

Springboard Unit 1 - Teachers.ocps.net

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

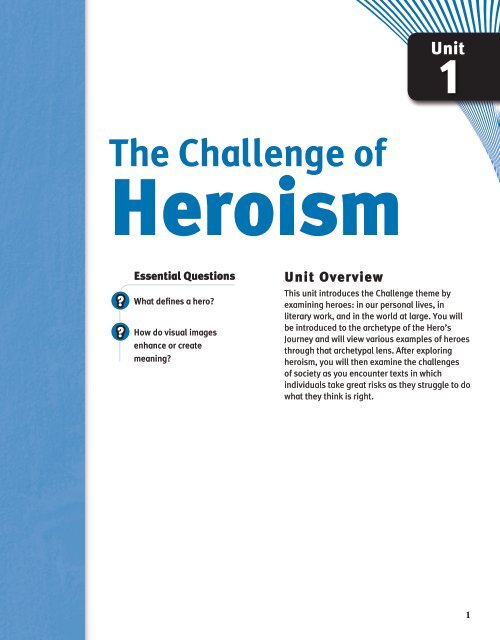

The Challenge of<br />

Heroism<br />

?<br />

?<br />

Essential Questions<br />

What defines a hero?<br />

How do visual images<br />

enhance or create<br />

meaning?<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> Overview<br />

<strong>Unit</strong><br />

1<br />

This unit introduces the Challenge theme by<br />

examining heroes: in our personal lives, in<br />

literary work, and in the world at large. You will<br />

be introduced to the archetype of the Hero’s<br />

Journey and will view various examples of heroes<br />

through that archetypal lens. After exploring<br />

heroism, you will then examine the challenges<br />

of society as you encounter texts in which<br />

individuals take great risks as they struggle to do<br />

what they think is right.

<strong>Unit</strong><br />

1<br />

Goals<br />

C To define various traits<br />

and types of heroes<br />

through multiple genres<br />

and texts<br />

C To understand the<br />

archetype of the hero’s<br />

journey and apply it<br />

to various scenarios in<br />

both print and nonprint<br />

texts<br />

C To analyze various<br />

literary, nonfiction, and<br />

nonprint texts<br />

ACAdemiC VoCABulAry<br />

Diction<br />

Archetype<br />

Definition Essay<br />

Nonprint Text<br />

Compare/Contrast<br />

Imagery<br />

The Challenge of Heroism<br />

SpringBoard® English Textual Power level 3<br />

Contents<br />

learning Focus: Taking Your Writing to the Next Level . . . . . . . . . . . 4<br />

Activities:<br />

1.1 Previewing the <strong>Unit</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5<br />

1.2 Challenges Word Wall . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6<br />

1.3 Tone: Word Sort . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8<br />

1.4 Emotional and Physical Challenges . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10<br />

Poetry: “A Man,” by Nina Cassian<br />

Poetry: “Moco Limping,” by David Nava Monreal<br />

1.5 Facing Challenges . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14<br />

*Film: From October Sky, directed by Joe Johnston<br />

1.6 Defining Heroic Qualities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16<br />

1.7 Heroes in Action . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17<br />

Article: “Love Triumphs: 6-year-old Becomes a Hero to<br />

a Band of Toddlers, Rescuers,” by Ellen Barry<br />

1.8 Historical Heroes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21<br />

Poetry: “O Captain! My Captain!” by Walt Whitman<br />

Poetry: “Frederick Douglass,” by Robert Hayden<br />

1.9 The Challenge of the Hero’s Journey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26<br />

1.10 The Refusal of the Call . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30<br />

*Film: From Batman Begins, directed by Christopher Nolan, or<br />

*Film: From Star Wars 1: Episode 1—The Phantom Menace,<br />

directed by George Lucas<br />

1.11 The Road of Trials . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31<br />

Narrative: From The Odyssey, by Homer<br />

1.12 A Different Kind of Heroine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .40<br />

*Film: From Mulan, directed by Tony Bancroft and Barry Cook<br />

1.13 Creating a Different Kind of Heroine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .42<br />

Article: “Woman Warrior,” by Corie Brown and Laura Shapiro<br />

1.14 An Everyday Hero . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .48<br />

Personal responses<br />

embedded Assessment 1 Writing a Definition Essay . . . . . . . . . . . 53<br />

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.<br />

learning Focus: Applying the Archetype in Text . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57<br />

1.15 Reading Utopia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58<br />

Novel: Excerpt from Utopia, by Thomas More<br />

1.16 Precise Words . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60<br />

*Novel: The Giver, by Lois Lowry<br />

1.17 Reading the Opening . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62<br />

*Film: From E.T., The Extra-Terrestrial, directed<br />

by Steven Spielberg<br />

1.18 Babies and Birthdays . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68<br />

1.19 Characterization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70<br />

1.20 The Circle of Life . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71<br />

1.21 Essential Attributes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73<br />

1.22 Rules in Society . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .74<br />

1.23 Coming to Your Senses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75<br />

Postcard: “The Heartiest of Season’s Greetings,”<br />

by Carl Nelson, December 1969<br />

1.24 Marking the Text . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .77<br />

1.25 Evolution of a Hero . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78<br />

1.26 An Ending to The Giver . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .79<br />

1.27 Author’s Purpose: Lowry’s Newbery Acceptance Speech . . . . . . .80<br />

Speech: Newbery Acceptance Speech, by Lois Lowry<br />

1.28 Alien Escape . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89<br />

*Film: From E.T., The Extra-Terrestrial, directed<br />

by Steven Spielberg<br />

1.29 Graphic Novels: Visualizing an Incident . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91<br />

Graphic Novel: Excerpt from Persepolis, by Marjane Satrapi<br />

embedded Assessment 2 Visualizing an Event in<br />

Jonas’s Journey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99<br />

unit reflection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102<br />

*Texts not included in these materials.

Learning Focus:<br />

Taking Your Writing to the Next Level<br />

Writers communicate to inform, to persuade, or to entertain. One genre of<br />

writing that you are very familiar with is narrative writing, in which you write<br />

to entertain. You are also familiar with expository writing, or writing to explain<br />

or inform.<br />

Good writers draw upon and blend a variety of genres and resources in order<br />

to create the strongest text possible. For example, an expository essay may<br />

be about a personal topic, with the purpose to explain or inform the audience<br />

about that personal topic.<br />

Writers use research in expository writing to support and elaborate upon their<br />

explanation of a topic. Research may come from a secondary source, such as<br />

an article on the Inter<strong>net</strong> or a news story, or from a primary source, such as<br />

an in-person interview or an observation. This information, when correctly<br />

incorporated into writing, strengthens the writer’s argument and solidifies<br />

his/her authority with the audience.<br />

Good writers follow this process to create effective written texts:<br />

C Prewriting includes clarifying the purpose for writing; identifying possible<br />

audiences; developing a thesis; identifying, organizing, and considering<br />

the relevance of known information; and determining the need for further<br />

research. After gathering information, the writer selects and develops<br />

major ideas, relevant reasons, supporting examples, and details. Then, the<br />

writer focuses the topic by considering whether the content is relevant,<br />

interesting, and meaningful to both the writer and audience.<br />

C Drafting involves generating a text that presents a coherent and smooth<br />

progression of ideas, includes supporting details and explanations,<br />

incorporates source materials as appropriate, and reaches a satisfactory<br />

conclusion. At this time, the writer also makes stylistic choices with<br />

language (e.g., word choice, sentence and paragraph organization and<br />

structure) to achieve intended effects. You may write multiple drafts during<br />

this step, each time building upon your ideas.<br />

C Revision requires evaluating the draft for clarity of focus, progression of<br />

ideas, development, organization, and appropriateness of conclusion<br />

in order to identify areas requiring further invention and research. The<br />

writer also evaluates stylistic choices with an awareness of purpose and<br />

audience.<br />

C Editing for conventions of standard written English, including grammar and<br />

mechanics (for example, spelling, capitalization, punctuation), is the final<br />

step in preparing your text for publication.<br />

SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.<br />

Previewing the <strong>Unit</strong><br />

SUGGESTED LEarninG STraTEGiES: close Reading, Graphic Organizer, KWL<br />

chart, Marking the text, Summarizing/Paraphrasing, think-Pair-Share<br />

Essential Questions<br />

1. What defines a hero?<br />

2. How do visual images enhance or create meaning?<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> Overview and Learning Focus<br />

Predict what you think this unit is about. Use the words or phrases<br />

that stood out to you when you read the <strong>Unit</strong> Overview and the<br />

Learning Focus.<br />

Embedded Assessment 1<br />

What knowledge must you have (what do you need to know) to succeed<br />

on Embedded assessment 1? What skills must you have (what must you<br />

be able to do)?<br />

Activity<br />

1.1<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism

Activity<br />

1.2 Challenges Word Wall<br />

AcAdeMic vocABulAry<br />

Diction refers to the writer’s<br />

choice of words and use of<br />

language.<br />

vocabulary Word<br />

SUGGESTED LEarninG STraTEGiES: Quickwrite, think Aloud,<br />

think-Pair-Share, Word Map<br />

Diction refers to word choice. Choose words in your Vocabulary<br />

notebook and on the Word Wall when you speak and write about<br />

challenges.<br />

Word Map<br />

definition: Synonyms:<br />

My experience with this concept:<br />

i haven’t really thought about this concept:<br />

i have only thought about this concept in<br />

Language arts class:<br />

i have applied this concept in other classes:<br />

i have applied this concept outside of school:<br />

SpringBoard® English Textual Power level 3<br />

Graphic representation (literal or symbolic)<br />

My level of understanding:<br />

i am still trying to understand this concept:<br />

i am familiar with this concept, but i am not<br />

comfortable applying it:<br />

i am very comfortable with this concept and<br />

i know how to apply it:<br />

i could teach this concept to another classmate:<br />

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.<br />

List three personal challenges you will (or will choose to) face this year.<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

For each challenge, list at least three steps you must take in order to<br />

meet this challenge successfully.<br />

challenge 1 challenge 2 challenge 3<br />

1. 1. 1.<br />

2. 2. 2.<br />

3. 3. 3.<br />

Quickwrite: What do you see as the most significant challenges facing<br />

the world, this country, and your community?<br />

Portfolio: Use your “challenges” brainstorming to decorate your<br />

Working Folder and Portfolio. Write the word Challenge large in the<br />

center of the folder cover. Place your brainstormed images, words, and<br />

phrases on the front of the folder. Follow your teacher’s guidelines to<br />

complete this assignment.<br />

Activity 1.2<br />

continued<br />

unit 1 • The Challenge of Heroism

Activity<br />

1.3 Tone: Word Sort<br />

SUGGESTED LEarninG STraTEGiES: Graphic Organizer, visualizing,<br />

Word Map<br />

Using the list at the right, fill in each box below with at least seven<br />

other words that have the same or similar denotation or meaning as<br />

the words below. The connotations may differ.<br />

SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

anxious sentimental<br />

sharp candid<br />

upset jittery<br />

mirthful morose<br />

boring mournful<br />

hesitant apprehensive<br />

joyful incensed<br />

agitated despondent<br />

sincere aromatic<br />

afraid elated<br />

poignant still<br />

outspoken pungent<br />

reeking scented<br />

composed lugubrious<br />

frank jovial<br />

irritated fretful<br />

placid odorous<br />

joking ecstatic<br />

unbiased enraged<br />

exultant tranquil<br />

peaceful jubilant<br />

blunt forthright<br />

vexed woeful<br />

serene livid<br />

soothing perfumed<br />

redolent desolate<br />

giddy fragrant<br />

infuriated fetid<br />

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.<br />

Understanding tone in prose and poetry can be challenging because<br />

the reader doesn’t have the speaker’s actual voice to help interpret<br />

meaning and attitude. instead, readers must depend on the nuances<br />

and connotations of words. To misinterpret tone is to misinterpret<br />

meaning.<br />

Find the eight words from the list on the previous page that do not fit<br />

in the tone word boxes and write them below. Create a category that<br />

fits the words.<br />

analyze the passage below and choose one of the tone words from the<br />

previous page that you think best describes the tone. Highlight the<br />

phrases or words that suggest the tone.<br />

Yikes. Why me? I never asked to be editor. I’ve only been on the<br />

newspaper staff for a year. I can’t be editor. The rest of the staff won’t<br />

listen to me. I won’t be able to deal with all those deadlines and what<br />

about the advertiser? I’m not sure I can handle the pressure. I feel<br />

overwhelmed just thinking about it. I like to write and read, but lead<br />

and edit seems like a different world. What am I going to do?<br />

Activity 1.3<br />

continued<br />

Literary terms<br />

tone is a writer’s or<br />

speaker’s attitude<br />

toward the subject.<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism

Activity<br />

1.4<br />

My Notes<br />

Emotional and Physical Challenges<br />

SUGGESTED LEaRNiNG STRaTEGiES: Marking the text, Notetaking,<br />

think-Pair-Share, tP-cAStt<br />

5<br />

10<br />

15<br />

P o e t r y<br />

10 SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

A b o u t t h e A u t h o r<br />

Nina Cassian was born in Romania in 1924 and now lives<br />

in New York City. She has written more than 50 volumes<br />

of work, including poetry, fiction, and books for children.<br />

Cassian is also a journalist, film critic, and composer of<br />

classical music.<br />

by Nina Cassian<br />

While fighting for his country, he lost an arm<br />

And was suddenly afraid:<br />

“From now on, I shall only be able to do things by halves.<br />

I shall reap half a harvest.<br />

I shall be able to play either the tune<br />

or the accompaniment on the piano,<br />

but never both parts together.<br />

I shall be able to bang with only one fist<br />

on doors, and worst of all<br />

I shall only be able to half hold<br />

my love close to me.<br />

There will be things I cannot do at all,<br />

applaud for example,<br />

at shows where everyone applauds.”<br />

From that moment on, he set himself to do<br />

everything with twice as much enthusiasm.<br />

And where the arm had been torn away<br />

a wing grew.<br />

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.<br />

Now use TP-CaSTT to examine Nina Cassian’s “a Man.”<br />

t – title: Think about the title before you read the poem. What do you<br />

think the poem might be about?<br />

P – Paraphrase: Read the poem and paraphrase parts of it you find<br />

difficult (put it into your own words). Examine the punctuation for clues<br />

about who is speaking and the idea expressed.<br />

c – connotation: Highlight words or phrases you see as significant.<br />

Think about their connotations. What ideas and feelings do you<br />

associate with the words?<br />

A – Attitude: What is the speaker’s attitude toward the situation?<br />

S – Shifts: are there shifts in speakers? in other words, does the person<br />

speaking change within the poem? Or does the attitude of the speaker<br />

change anywhere in the poem? if so, draw a line where the shift occurs<br />

and explain the shift in the My Notes section.<br />

t – title: Look at the title again. How have your ideas about the<br />

meaning of the title changed?<br />

t – theme: What is the poet saying? What is the overall message or<br />

theme of the poem?<br />

Activity 1.4<br />

continued<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 11

Activity 1.4<br />

continued<br />

Grammar &UsaGe<br />

Put quotation marks<br />

around words and phrases<br />

you take directly from the<br />

poem to show that you are<br />

quoting verbatim.<br />

Emotional and Physical Challenges<br />

12 SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

Working in pairs, read the poem, “Moco Limping.” Use the TP-CaSTT<br />

strategy and the questions below to examine it carefully.<br />

t – title: Think about the title before you read the poem. What do you<br />

think the poem might be about?<br />

P – Paraphrase: Put into your own words parts of the poem you find<br />

difficult. Examine punctuation for clues about who is speaking and the<br />

ideas expressed.<br />

c – connotation: Highlight words you see as significant, even if you<br />

don’t know them. What ideas or feelings are associated with the words<br />

or phrases you have chosen?<br />

A – Attitude: What is the speaker’s attitude toward the situation?<br />

S – Shifts: are there shifts in speaker? Shifts in attitude? Draw a line<br />

where you see a shift.<br />

t – title: Look at the title again. How have your ideas about the<br />

meaning of the title changed?<br />

t – theme: What is the author saying? What is his comment on his<br />

subject? What is the overall message or theme of the poem?<br />

Writing Prompt: Think back to the discussion regarding challenges, then<br />

write a personal response to “Moco Limping.” Can you relate personally<br />

to the challenges faced by Moco and his owner? Why or why not?<br />

Explain using words and phrases from the poem. Notice how words and<br />

phrases from the poem are incorporated in the following example:<br />

I’ve never had a dog that was a “brutal hunter” or even a “rickety<br />

little canine” like Moco. My dogs have all been lovable mutts who<br />

liked to chase balls and run away from me when I called them.<br />

But I can relate to the feel of his “warm fur” and his eyes that “cry<br />

out with life.” My dog, Rex, looks at me with the saddest brown<br />

eyes when I leave him. But he is always eager to see me when I<br />

come home in the evening, and I love rubbing my face on his soft<br />

furry ears. So I understand the speaker’s affection for his dog even<br />

though he is crippled.<br />

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.<br />

P o e t r y<br />

by David Nava Monreal<br />

A b o u t t h e A u t h o r<br />

David Nava Monreal’s short stories have been published<br />

in Seguaro and The Bilingual Review. He has also<br />

published the books The New Neighbor and Other Stories,<br />

Choosing Sides, and The Epic Novel. Monreal grew up in<br />

California’s central valley.<br />

My dog hobbles with a stick<br />

of a leg that he drags behind<br />

him as he moves.<br />

And I was a man that wanted a<br />

beautiful, noble animal as a pet.<br />

I wanted him to be strong and<br />

capture all the attention by<br />

the savage grace of his gait.<br />

I wanted him to be the first dog<br />

howling in the pack,<br />

the leader, the brutal hunter<br />

that broke through<br />

the woods with thunder.<br />

But, instead he’s<br />

this rickety little canine<br />

that leaves trails in the dirt<br />

with his club foot.<br />

He’s the stumbler that trips while<br />

chasing lethargic bees and butterflies.<br />

It hurts me tosee him so<br />

abnormal, so clumsy and stupid.<br />

My vain heart weeps knowing he is mine.<br />

But then he turns my way and<br />

looks at me with<br />

eyes that cry outwith life.<br />

He jumps at me with<br />

his feeble paws.<br />

I feel his warm fur<br />

and his imperfection is<br />

forgotten.<br />

5<br />

10<br />

15<br />

20<br />

25<br />

My Notes<br />

Activity 1.4<br />

continued<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 13

Activity<br />

1.5<br />

Facing Challenges<br />

SUGGESTED LEarninG STraTEGiES: Graphic Organizer<br />

October Sky is based on a true story. it was 1957 in a coal mining town<br />

in West Virginia. Most boys went into the coal mines as soon as they<br />

graduated from high school. it was expected. it was tradition. it was a<br />

dangerous job that often meant an early death.<br />

One boy, Homer Hickam, Jr., dared to go beyond the expected, thanks<br />

in part to his teacher, Miss riley. Over the objection of his father, he<br />

persevered to win a national science fair, a college scholarship, and<br />

most importantly, a life out of the coal mine as a rocket scientist for<br />

naSa.<br />

Watch each clip and consider how each scene reflects a particular<br />

challenge for Homer. Take notes on a different aspect during each<br />

viewing.<br />

Scene<br />

Trying out for<br />

the football<br />

team<br />

Building a<br />

rocket<br />

What challenges<br />

does Homer face?<br />

14 SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

What action does<br />

Homer take in<br />

response to the<br />

challenge(s)?<br />

What’s the end<br />

result?<br />

How would a<br />

different choice<br />

have affected the<br />

outcome?<br />

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.<br />

Scene<br />

First flight<br />

Change of<br />

career plans<br />

He didn’t start<br />

the fire<br />

Trouble at the<br />

science fair<br />

What challenges<br />

does Homer face?<br />

What action does<br />

Homer take in<br />

response to the<br />

challenge(s)?<br />

thesis Statement: Write a thesis statement about Homer’s challenges<br />

and his reactions to those challenges.<br />

What’s the end<br />

result?<br />

Activity 1.5<br />

continued<br />

How would a<br />

different choice<br />

have affected the<br />

outcome?<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 15

Activity<br />

1.6<br />

AcAdEmic vocABulAry<br />

A definition essay is writing<br />

that explains, or defines,<br />

what a topic means.<br />

Defining Heroic Qualities<br />

SUGGESTED LEARninG STRATEGiES: drafting, marking the draft,<br />

think-Pair-Share, Word map<br />

16 SpringBoard® English Textual Power level 3<br />

1. Generate a list of adjectives to describe qualities of a heroic person.<br />

When you write a definition essay, you can use these strategies of<br />

definition:<br />

• Paragraphs using the function strategy demonstrate how the<br />

concept functions or operates in the real world.<br />

• Paragraphs using the example strategy use examples to help the<br />

reader understand your definition. These examples often come<br />

from texts.<br />

• Paragraphs using the negation strategy explain what something<br />

is by showing what it is not. Using negation helps to contrast your<br />

definition with others’ definitions.<br />

2. Writing Prompt: Respond to the Essential Question: What defines a<br />

hero? Use all three definition strategies in your response, and use<br />

examples from texts you have encountered in this unit.<br />

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.<br />

Heroes in Action<br />

SUGGESTED LEarninG STraTEGiES: Group Discussion, Notetaking,<br />

Quickwrite, Summarizing/Paraphrasing<br />

Anticipation Guide<br />

read the following statements. Mark each blank with either an A if you<br />

agree with the statement or a D if you disagree with the statement.<br />

Go with your first instinct or gut reaction and try not to linger on your<br />

decisions. When you complete the questionnaire, you will share your<br />

decisions with a classmate.<br />

1. all heroes are brave.<br />

2. Heroes are created by the events around them.<br />

3. Most people have a hero.<br />

4. You cannot be defeated and still be considered a hero.<br />

5. in order to be a true hero, a person would have to risk his or<br />

her life.<br />

6. if all you want is fame and glory, then regardless of what you<br />

do, you should not be called a hero.<br />

7. all heroes are human.<br />

8. real-life heroes are not like the heroes we read about in<br />

books or watch in movies.<br />

9. Heroes are always handsome or beautiful.<br />

10. if you perform one heroic deed, then you are a hero.<br />

11. Heroes are always famous.<br />

12. i know a person whom i consider a hero.<br />

13. Heroic deeds happen every day, all around us.<br />

14. Heroes must face tragedy.<br />

15. Heroes never return to normal life.<br />

16. Heroes are always adults.<br />

Activity<br />

1.7<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 17

Activity 1.7<br />

continued<br />

Before Reading<br />

Heroes in Action<br />

Brainstorm a list of events or challenges or situations in which an<br />

ordinary person might act heroically.<br />

Quickwrite: Write about an event that involved someone acting<br />

heroically. This may be an event from your brainstormed list, an event<br />

that you saw personally, or one that you have heard or read about.<br />

Perhaps it is an event that you saw on the news or depicted in a movie.<br />

Write about the most important aspects of the event. (What was the<br />

event? Who did it involve? When did it happen? Where did it occur?<br />

Why is it an important event? How did it involve heroism?)<br />

During Reading<br />

as you read the following article, take notes in the My notes section<br />

on the 5 Ws and an H questions: Who, What, Where, When, Why, and<br />

How. Paraphrase the facts of the article, rather than quoting passages<br />

verbatim. Your How? note should answer the question “How can the boy<br />

be considered a hero?”<br />

remember, paraphrasing a text requires care. When you paraphrase,<br />

you must use different language and sentence structure. if a paraphrase<br />

is a word-for-word match to the original text or so close that it is<br />

difficult to tell the difference, it could be called plagiarism.<br />

18 SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.<br />

A r t i c l e<br />

Love triumphs:<br />

6-year-Old Becomes<br />

a Hero to Band of<br />

toddlers, Rescuers<br />

Hurricane Katrina - Tense days lead to reunion of kids and<br />

their moms<br />

by Ellen Barry<br />

LoS anGELES TiMES<br />

Baton Rouge, L.A. – In the chaos that was Causeway Boulevard,<br />

this group of evacuees stood out: a 6-year-old boy walking down the<br />

road, holding a 5-month-old, surrounded by five toddlers who followed<br />

him around as if he were their leader. They were holding hands. Three<br />

of the children were about 2 years old, and one was wearing only<br />

diapers. A 3-year-old girl had her 14-month-old brother in tow. The<br />

6-year-old spoke for all of them, and he said his name was Deamonte<br />

Love. After their rescue Thursday, paramedics in the Baton Rouge<br />

rescue operations headquarters tried to coax their names out of them.<br />

Transporting the children alone was “the hardest thing I’ve ever<br />

done in my life, knowing that their parents are either dead” or that they<br />

had been abandoned, said Pat Coveney, a Houston emergency medical<br />

technician who put them into the back of his ambulance and drove<br />

them out of New Orleans. “It goes back to the same thing,” he said.<br />

“How did a 6-year-old end up being in charge of six babies?<br />

At the rescue headquarters, the children ate cafeteria food and fell<br />

into a deep sleep. Deamonte gave his address, his phone number, and<br />

the name of his elementary school. He said the 5-month-old was his<br />

brother, Darynael, that two others were his cousins, Tyreek and Zoria.<br />

The other three lived in his apartment building. The children were<br />

clean and healthy, said Joyce Miller, a nurse who examined them. It was<br />

clear, she said, that “time had been taken with those kids.” The baby was<br />

“fat and happy.”<br />

The children were transferred to a shelter operated by the<br />

Department of Social Services, rooms full of toys and cribs where<br />

mentors from the Big Buddy Program were on hand. For the next two<br />

days, the staff did detective work. One of the 2-year-olds steadfastly<br />

refused to say her name until a worker took her picture with a digital<br />

camera and showed it to her. The little girl pointed at it and cried out,<br />

My Notes<br />

W<br />

W<br />

W<br />

W<br />

W<br />

H<br />

Activity 1.7<br />

continued<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 19

Activity 1.7<br />

continued<br />

My Notes<br />

Heroes in Action<br />

“Gabby!” One of the boys—with a halo of curly hair—had a G printed<br />

on his T-shirt when he arrived; when volunteers started calling him G,<br />

they noticed that he responded. Deamonte began to give more details<br />

to Derrick Robertson, a 27-year-old Big Buddy mentor: How he saw his<br />

mother cry when he was loaded onto the helicopter. How he promised<br />

he’d take care of his brother.<br />

Later Saturday night, they found Deamonte’s mother, who was in<br />

a shelter in San Antonio along with the four mothers of the other five<br />

children. Catrina Williams, 26, saw her children’s pictures on a Web<br />

site set up over the weekend by the National Center for Missing and<br />

Exploited Children. By Sunday, a private plane from Angel Flight was<br />

waiting to take the children to Texas.<br />

In a phone interview, Williams said she is the kind of mother who<br />

doesn’t let her children out of her sight. What happened on Thursday,<br />

she said, was that her family, trapped in an apartment building, began<br />

to feel desperate. The water wasn’t going down and they had been living<br />

without light, food or air conditioning for four days. The baby needed<br />

milk and the milk was gone. So she decided they would evacuate by<br />

helicopter. When a helicopter arrived to pick them up, they were told<br />

to send the children first and that the helicopter would be back in 25<br />

minutes. She and her neighbors had to make a quick decision. It was a<br />

wrenching moment, Williams’ father, Adrian Love, told her to send the<br />

children ahead.<br />

“I told them to go ahead and give them up because me, I would give<br />

my life for my kids. They should feel the same way,” said Love, 48.<br />

His daughter and her friends followed his advice. “We did what we<br />

had to do for our kids because we love them,” Williams said.<br />

The helicopter didn’t come back. While the children were transported<br />

to Baton Rouge, their parents wound up in San Antonio, and although<br />

Williams was reassured that they would be reunited, days passed without<br />

any contact. On Sunday, she was elated. “All I know is, I just want to see<br />

my kids,” she said. “Everything else will just fall into place.”<br />

After Reading<br />

20 SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

on separate paper summarize, in three or four sentences, the main<br />

points of the article (use your 5Ws and H notes).<br />

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.<br />

Activity<br />

Historical Heroes 1.8<br />

SUGGESTED LEARNING STRATEGIES: Diffusing, KWHL chart, Marking<br />

the text, Skimming/Scanning, tP-cAStt<br />

Before Reading<br />

Fill out the KWHL chart on what you know about the following:<br />

• American Civil War<br />

• Abraham Lincoln<br />

• Frederick Douglass<br />

Civil War:<br />

Abraham<br />

Lincoln:<br />

Frederick<br />

Douglass:<br />

K (What I<br />

Know)<br />

W (What I Want<br />

to know)<br />

H (How I will<br />

learn it)<br />

L (What I<br />

Learned)<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 21

Activity 1.8<br />

continued<br />

Word<br />

ConneCtions<br />

Allegory has the Greek<br />

roots -allo- or -all-,<br />

meaning “other” and<br />

-gor- from the words<br />

marketplace and speaking<br />

publicly.<br />

The essential meaning<br />

of allegory is speaking<br />

“otherwise” or<br />

“figuratively.”<br />

Historical Heroes<br />

During Reading<br />

22 SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

“O captain! My captain!”<br />

The poem “O Captain! My Captain!” is an example of an allegory.<br />

Allegory is a form of extended metaphor, in which objects, persons, and<br />

actions in a narrative have meanings outside the narrative itself. The<br />

underlying meaning has moral, social, religious, or political significance,<br />

and characters are often personifications of abstract ideas such as<br />

charity, greed, or envy. Thus an allegory is a story with two meanings, a<br />

literal meaning and a symbolic meaning.<br />

Whitman wrote this poem as a memorial for Abraham Lincoln after<br />

his death.<br />

1. As your teacher reads the poem, mark the text by circling all words<br />

having to do with a ship or voyage. Also circle the word Captain and<br />

its synonyms in the poem.<br />

2. Who is Whitman referring to as the “Captain” of the ship?<br />

3. What do you think the ship is representative of?<br />

“Frederick Douglass”<br />

As your teacher reads this poem, mark the text by circling the words it<br />

and thing every time they are used in the poem.<br />

4. What do the words it and thing refer to in the poem?<br />

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.<br />

P o e t r y<br />

by Walt Whitman<br />

O Captain! my Captain! our fearful trip is done;<br />

The ship has weather’d every rack, the prize we sought is<br />

won;<br />

The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting,<br />

While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring:<br />

But O heart! heart! heart!<br />

O the bleeding drops of red,<br />

Where on the deck my Captain lies,<br />

Fallen cold and dead.<br />

O Captain! my Captain! rise up and hear the bells;<br />

Rise up—for you the flag is flung— or you the bugle trills;<br />

For you bouquets and ribbon’d wreaths—for you the<br />

shores a-crowding,<br />

For you they call, the swaying mass, their eager faces<br />

turning;<br />

Here Captain! dear father!<br />

This arm beneath your head;<br />

It is some dream that on the deck,<br />

You’ve fallen cold and dead.<br />

My Captain does not answer, his lips are pale and still;<br />

My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor will;<br />

The ship is anchored safe and sound, its voyage closed and<br />

done;<br />

From fearful trip the victor ship comes in with object won:<br />

Exult O shores, and ring O bells!<br />

But I with mournful tread,<br />

Walk the deck my Captain lies,<br />

Fallen cold and dead.<br />

5<br />

10<br />

15<br />

20<br />

25<br />

My Notes<br />

t<br />

P<br />

c<br />

A<br />

S<br />

t<br />

t<br />

Activity 1.8<br />

continued<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 23

Activity 1.8<br />

continued<br />

My Notes<br />

Historical Heroes<br />

5<br />

10<br />

P o e t r y<br />

24 SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

A B o u t t h e A u t h o R s<br />

Walt Whitman (1819–1892) is now considered one of America’s<br />

greatest poets, but his untraditional poetry was not well<br />

received during his lifetime. As a young man, he worked as<br />

a printer and a journalist while writing free-verse poetry. His<br />

collection of poems, Leaves of Grass, first came out in 1855, and<br />

he revised and added to it several times over the years.<br />

Robert Hayden (1913 –1980) grew up in a poor neighborhood of<br />

Detroit, won a scholarship to college, and became a politically<br />

active writer. One of his interests was African American history,<br />

which he explores in some of his poetry.<br />

by Robert Hayden<br />

When it is finally ours, this freedom, this liberty, this<br />

beautiful<br />

and terrible thing, needful to man as air,<br />

usable as earth; when it belongs at last to all,<br />

when it is truly instinct, brain matter, diastole, systole, 1<br />

reflex action; when it is finally won; when it is more<br />

than the gaudy mumbo jumbo of politicians:<br />

this man, this Douglass, this former slave, this Negro<br />

beaten to his knees, exiled, visioning a world<br />

where none is lonely, none hunted, alien,<br />

this man, superb in love and logic, this man<br />

shall be remembered. Oh, not with statues’ rhetoric,<br />

not with legends and poems and wreaths of bronze alone,<br />

but with the lives grown out of his life, the lives<br />

fleshing his dream of the beautiful, needful thing.<br />

1 diastole, systole: the normal, rhythmic opening and closing of the heart.<br />

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.<br />

After Reading<br />

In small groups, use the TP-CASTT strategy to analyze and discuss both<br />

poems. Write your analysis in the My Notes space or on separate paper.<br />

Writing Prompt: Using your TP-CASTT notes, write a literary analysis<br />

paragraph in the space below in which you address the following<br />

questions. Use textual evidence to support your analysis.<br />

• What traits do Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass exhibit to<br />

be considered heroes?<br />

• How does the tone of either poem support the perception of<br />

Lincoln or Douglass as a hero?<br />

Activity 1.8<br />

continued<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 25

Activity<br />

1.9<br />

Word<br />

ConneCtions<br />

The Greek prefix arch- in<br />

archetype means “chief”<br />

or “principal” or “first.”<br />

This prefix is also found in<br />

archaic, archeology, and<br />

archive.<br />

The Greek root -type,<br />

meaning “impression”<br />

or “type,” also occurs in<br />

typical and stereotype.<br />

The Challenge of the Hero’s Journey<br />

SUGGESTED LEARNING STRATEGIES: Graphic Organizer, Revisiting<br />

Prior Work, think Aloud, Paraphrasing, Word Map<br />

1. Define stereotype:<br />

26 SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

2. Is there a stereotypical hero?<br />

An archetype is a character, symbol, story pattern, or other element<br />

that is common to human experience across cultures and that occurs<br />

frequently in literature, myth, and folklore.<br />

3. How are the ideas of stereotype and archetype different? How are<br />

they similar?<br />

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.<br />

4. According to Joseph Campbell, the hero’s journey can be called<br />

archetypical because all heroes’ journeys follow a similar pattern.<br />

Following are what Campbell considers the key elements of such a<br />

journey. Think about different heroes’ stories you have encountered,<br />

and look for connections between their story and this outline. Your<br />

teacher will give you some notes and examples as you discuss each<br />

category. Restate in your own words each stage of the hero’s journey.<br />

StEPS<br />

Activity 1.9<br />

Stage 1: Departure In Your Own Words Notes/Examples<br />

the call to Adventure: The<br />

future hero is first given<br />

notice that his or her life is<br />

going to change.<br />

Refusal of the call: The<br />

future hero often refuses to<br />

accept the Call to Adventure.<br />

The refusal may stem from a<br />

sense of duty, an obligation,<br />

a fear, or insecurity.<br />

the Beginning of the<br />

Adventure: This is the point<br />

where the hero actually<br />

begins the adventure,<br />

leaving the known limits<br />

of his or her world and<br />

venturing into an unknown<br />

and dangerous realm where<br />

the rules and limits are<br />

unknown.<br />

continued<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 27

Activity 1.9<br />

continued<br />

StEPS<br />

The Challenge of the Hero’s Journey<br />

Stage 2: Initiation In Your Own Words Notes/Examples<br />

the Road of trials: The road<br />

of trials is a series of tests,<br />

tasks, or challenges that the<br />

hero must undergo as part<br />

of the hero’s transformation.<br />

Often the hero fails one or<br />

more of these tests, which<br />

often occur in threes.<br />

the Experience with<br />

Unconditional Love: During<br />

the Road of Trials, the hero<br />

experiences unconditional<br />

love and support from<br />

a friend, mentor, family<br />

member. This love often<br />

drives the hero to continue<br />

on the journey, even when<br />

the hero doubts him/herself.<br />

the Ultimate Boon: The goal<br />

of the quest is achieved. All<br />

the previous steps serve<br />

to prepare and purify the<br />

person for this step.<br />

28 SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.<br />

StEPS<br />

Activity 1.9<br />

Stage 3: Return In Your Own Words Notes/Examples<br />

Refusal of the Return: When<br />

the goal of the adventure has<br />

been accomplished, the hero<br />

may refuse to return with the<br />

boon or gift, either because the<br />

hero doubts the return will bring<br />

change, or because the hero<br />

prefers to stay in a better place<br />

rather than return to a normal<br />

life of pain and trouble.<br />

the Magic Flight: The hero<br />

experiences adventure and<br />

perhaps danger as he or she<br />

returns to life as it was before<br />

the adventure.<br />

Rescue from Without: Just<br />

as the hero may need guides<br />

and assistants on the quest,<br />

oftentimes he or she must have<br />

powerful guides and rescuers<br />

to bring him or her back to<br />

everyday life, especially if the<br />

hero has been wounded or<br />

weakened by the experience. Or,<br />

perhaps the hero doesn’t realize<br />

that it is time to return, that he<br />

or she can return, or that others<br />

need his or her gift.<br />

the crossing, or Return<br />

threshold: At this final point in<br />

the adventure, the hero must<br />

retain the wisdom gained on the<br />

quest, integrate that wisdom<br />

into his or her previous life, and<br />

perhaps decide how to share<br />

the wisdom with the rest of the<br />

world.<br />

continued<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 29

Activity<br />

1.10 The Refusal of the Call<br />

SUGGESTED LEARNING STRATEGIES: Graphic Organizer, Summarizing<br />

Your teacher will show film clips illustrating a hero’s journey. Use the<br />

graphic organizer below or separate paper to take notes.<br />

title of Film: Summary of Scene:<br />

connection to the “Refusal of the call” Outcome if the call is never accepted:<br />

Other Examples:<br />

30 SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.<br />

The Road of Trials<br />

SUGGESTED LEARNING STRATEGIES: Diffusing, Drafting, Graphic<br />

Organizer, Notetaking<br />

Read the story of Odysseus and the Cyclops. Complete the organizer<br />

with adjectives that describe Odysseus. Note details from the story that<br />

support your descriptions.<br />

Physical Characteristics: Mental Characteristics:<br />

Social Characteristics: Moral Characteristics:<br />

Trials/Challenges Faced:<br />

Activity<br />

1.11<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 31

Activity 1.11<br />

continued<br />

My Notes<br />

The Road of Trials<br />

N a r r a t i v e<br />

A b o u T T h e A u T h o r<br />

Homer is the traditionally accepted author of two famous epic<br />

poems, the The Iliad and the The Odyssey. No biography of<br />

Homer exists, and scholars disagree about whether he was the<br />

sole author or whether Homer was a name chosen by several<br />

writers who contributed to the works. Some scholars believe<br />

that the poems evolved through oral tradition over a period of<br />

centuries and are the collective work of many poets.<br />

From<br />

by Homer<br />

Translation by Tony Kline<br />

BOOk IX: 152–192<br />

Odysseus Tells His Tale: THe CyClOps’ Cave<br />

Looking across to the land of the neighboring Cyclopes, 1 we could<br />

see smoke and hear their voices, and the sound of their sheep and<br />

goats. Sun set and darkness fell, and we settled to our rest on the shore.<br />

As soon as rosy-fingered Dawn appeared, I gathered my men<br />

together, saying: “The rest of you loyal friends stay here, while I and my<br />

crew take ship and try and find out who these men are, whether they<br />

are cruel, savage and lawless, or good to strangers, and in their hearts<br />

fear the gods.”<br />

With this I went aboard and ordered my crew to follow and loose<br />

the cables. They boarded swiftly and took their place on the benches<br />

then sitting in their rows struck the grey water with their oars. When we<br />

had reached the nearby shore, we saw a deep cave overhung with laurels<br />

at the cliff ’s edge close to the sea. Large herds of sheep and goats were<br />

penned there at night and round it was a raised yard walled by deep-set<br />

stones, tall pines and high-crowned oaks. There a giant spent the night,<br />

1 Cyclopes: one-eyed giants<br />

32 springBoard® english Textual power Level 3<br />

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.<br />

one that grazed his herds far off, alone, and keeping clear of others, lived<br />

in lawless solitude. He was born a monster and a wonder, not like any<br />

ordinary human, but like some wooded peak of the high mountains,<br />

that stands there isolated to our gaze.’<br />

Bk IX: 193–255<br />

Odysseus Tells His Tale: pOlypHemus reTurns<br />

‘Then I ordered the rest of my loyal friends to stay there and guard<br />

the ship, while I selected the twelve best men and went forward. I<br />

took with me a goatskin filled with dark sweet wine that Maron, son<br />

of Euanthes, priest of Apollo guardian god of Ismarus, had given me,<br />

because out of respect we protected him, his wife and child. He offered<br />

me splendid gifts, seven talents of well-wrought gold, and a silver<br />

mixing-bowl: and wine, twelve jars in all, sweet unmixed wine, a divine<br />

draught. None of his serving-men and maids knew of this store, only<br />

he and his loyal wife, and one housekeeper. When they drank that<br />

honeyed red wine, he would pour a full cup into twenty of water, and<br />

the bouquet that rose from the mixing bowl was wonderfully sweet: in<br />

truth no one could hold back. I filled a large goatskin with the wine,<br />

and took it along, with some food in a bag, since my instincts told me<br />

the giant would come at us quickly, a savage being with huge strength,<br />

knowing nothing of right or law.<br />

Soon we came to the cave, and found him absent; he was grazing<br />

his well-fed flocks in the fields. So we went inside and marveled at its<br />

contents. There were baskets full of cheeses, and pens crowded with<br />

lambs and kids, each flock with its firstlings, later ones, and newborn<br />

separated. The pails and bowls for milking, all solidly made, were<br />

swimming with whey. At first my men begged me to take some cheeses<br />

and go, then to drive the lambs and kids from the pens down to the<br />

swift ship and set sail. But I would not listen, though it would have<br />

been best, wishing to see the giant himself, and test his hospitality.<br />

When he did appear he proved no joy to my men.<br />

So we lit a fire and made an offering, and helped ourselves to the<br />

cheese, and sat in the cave eating, waiting for him to return, shepherding<br />

his flocks. He arrived bearing a huge weight of dry wood to burn at<br />

suppertime, and he flung it down inside the cave with a crash. Gripped<br />

by terror we shrank back into a deep corner. He drove his well-fed flocks<br />

into the wide cave, the ones he milked, leaving the rams and he-goats<br />

outside in the broad courtyard. Then he lifted his door, a huge stone,<br />

and set it in place. Twenty-two four-wheeled wagons could not have<br />

carried it, yet such was the great rocky mass he used for a door. Then he<br />

sat and milked the ewes, and bleating goats in order, putting her young<br />

My Notes<br />

Activity 1.11<br />

continued<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 33

Activity 1.11<br />

continued<br />

My Notes<br />

The Road of Trials<br />

34 springBoard® english Textual power Level 3<br />

to each. Next he curdled half of the white milk, and stored the whey in<br />

wicker baskets, leaving the rest in pails for him to drink for his supper.<br />

When he had busied himself at his tasks, and kindled a fire, he suddenly<br />

saw us, and said: “Strangers, who are you? Where do you sail from over<br />

the sea-roads? Are you on business, or do you roam at random, like<br />

pirates who chance their lives to bring evil to others?” ’<br />

Bk IX:256–306<br />

Odysseus Tells His Tale: Trapped<br />

‘Our spirits fell at his words, in terror at his loud voice and<br />

monstrous size. Nevertheless I answered him, saying; “We are<br />

Achaeans, returning from Troy, driven over the ocean depths by every<br />

wind that blows. Heading for home we were forced to take another<br />

route, a different course, as Zeus, 2 I suppose, intended. We are followers<br />

of Agamemnon, Atreus’ son, whose fame spreads widest on earth,<br />

so great was that city he sacked and host he slew. But we, for our<br />

part, come as suppliant to your knees, hoping for hospitality, and the<br />

kindness that is due to strangers. Good sir, do not refuse us: respect the<br />

gods. We are suppliants and Zeus protects visitors and suppliants, Zeus<br />

the god of guests, who follows the steps of sacred travelers.”<br />

His answer was devoid of pity. “Stranger, you are a foreigner or a fool,<br />

telling me to fear and revere the gods, since the Cyclopes care nothing<br />

for aegis-bearing Zeus: we are greater than they. I would spare neither<br />

you nor your friends, to evade Zeus’ anger, but only as my own heart<br />

prompted. But tell me, now, where you moored your fine ship, when you<br />

landed. Was it somewhere nearby, or further off? I’d like to know.”<br />

His words were designed to fool me, but failed. I was too wise<br />

for that, and answered him with cunning words: “Poseidon, 3 Earth-<br />

Shaker, smashed my ship to pieces, wrecking her on the rocks that edge<br />

your island, driving her close to the headland so the wind threw her<br />

onshore. But I and my men here escaped destruction.”<br />

Devoid of pity, he was silent in response, but leaping up laid hands<br />

on my crew. Two he seized and dashed to the ground like whelps, and<br />

their brains ran out and stained the earth. He tore them limb from<br />

limb for his supper, eating the flesh and entrails, bone and marrow, like<br />

a mountain lion, leaving nothing. Helplessly we watched these cruel<br />

acts, raising our hands to heaven and weeping. When the Cyclops had<br />

filled his huge stomach with human flesh, and had drunk pure milk, he<br />

lay down in the cave, stretched out among his flocks. Then I formed a<br />

2 Zeus: the king of the gods<br />

3 Poseidon: god of the sea and of earthquakes<br />

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.<br />

courageous plan to steal up to him, draw my sharp sword, and feeling<br />

for the place where the midriff supports the liver, stab him there. But<br />

the next thought checked me. Trapped in the cave we would certainly<br />

die, since we’d have no way to move the great stone from the wide<br />

entrance. So, sighing, we waited for bright day.’<br />

Bk IX:307–359<br />

Odysseus Tells His Tale: Offering THe CyClOps wine<br />

‘As soon as rosy-fingered Dawn appeared, Cyclops relit the fire.<br />

Then he milked the ewes, and bleating goats in order, putting her<br />

young to each. When he had busied himself at his tasks, he again seized<br />

two of my men and began to eat them. When he had finished he drove<br />

his well-fed flocks from the cave, effortlessly lifting the huge door<br />

stone, and replacing it again like the cap on a quiver. Then whistling<br />

loudly he turned his flocks out on to the mountain slopes, leaving me<br />

with murder in my heart searching for a way to take vengeance on him,<br />

if Athene 4 would grant me inspiration. The best plan seemed to be this:<br />

The Cyclops’ huge club, a trunk of green olive wood he had cut to<br />

take with him as soon as it was seasoned, lay next to a sheep pen. It was<br />

so large and thick that it looked to us like the mast of a twenty-oared<br />

black ship, a broad-beamed merchant vessel that sails the deep ocean.<br />

Approaching it, I cut off a six-foot length, gave it to my men and told<br />

them to smooth the wood. Then standing by it I sharpened the end to<br />

a point, and hardened the point in the blazing fire, after which I hid<br />

it carefully in a one of the heaps of dung that lay around the cave. I<br />

ordered the men to cast lots as to which of them should dare to help me<br />

raise the stake and twist it into the Cyclops’ eye when sweet sleep took<br />

him. The lot fell on the very ones I would have chosen, four of them,<br />

with myself making a fifth.<br />

He returned at evening, shepherding his well-fed flocks. He herded<br />

them swiftly, every one, into the deep cave, leaving none in the broad<br />

yard, commanded to do so by a god, or because of some premonition.<br />

Then he lifted the huge door stone and set it in place, and sat down to<br />

milk the ewes and bleating goats in order, putting her young to each.<br />

But when he had busied himself at his tasks, he again seized two of my<br />

men and began to eat them. That was when I went up to him, holding<br />

an ivy-wood bowl full of dark wine, and said: “Here, Cyclops, have<br />

some wine to follow your meal of human flesh, so you can taste the sort<br />

of drink we carried in our ship. I was bringing the drink to you as a gift,<br />

hoping you might pity me and help me on my homeward path:<br />

4 Athene: goddess of wisdom, the arts, and war<br />

My Notes<br />

Activity 1.11<br />

continued<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 35

Activity 1.11<br />

continued<br />

My Notes<br />

The Road of Trials<br />

36 springBoard® english Textual power Level 3<br />

but your savagery is past bearing. Cruel man, why would anyone on<br />

earth ever visit you again, when you behave so badly?”<br />

At this, he took the cup and drained it, and found the sweet drink<br />

so delightful he asked for another draught: “Give me more, freely, then<br />

quickly tell me your name so I may give you a guest gift, one that will<br />

please you. Among us Cyclopes the fertile earth produces rich grape<br />

clusters, and Zeus’ rain swells them: but this is a taste from a stream of<br />

ambrosia and nectar.” ’<br />

Bk IX:360–412<br />

Odysseus Tells His Tale: Blinding THe CyClOps<br />

‘As he finished speaking I handed him the bright wine. Three times<br />

I poured and gave it to him, and three times, foolishly, he drained it.<br />

When the wine had fuddled his wits I tried him with subtle words:<br />

“Cyclops, you asked my name, and I will tell it: give me afterwards a<br />

guest gift as you promised. My name is Nobody. Nobody, my father,<br />

mother, and friends call me.”<br />

Those were my words, and this his cruel answer: “Then, my gift is<br />

this. I will eat Nobody last of all his company, and all the others<br />

before him.”<br />

As he spoke, he reeled and toppled over on his back, his thick neck<br />

twisted to one side, and all-conquering sleep overpowered him. In his<br />

drunken slumber he vomited wine and pieces of human flesh. Then<br />

I thrust the stake into the depth of the ashes to heat it, and inspired<br />

my men with encouraging words, so none would hang back from<br />

fear. When the olivewood stake was glowing hot, and ready to catch<br />

fire despite its greenness, I drew it from the coals, then my men stood<br />

round me, and a god breathed courage into us. They held the sharpened<br />

olivewood stake, and thrust it into his eye, while I threw my weight on<br />

the end, and twisted it round and round, as a man bores the timbers of<br />

a ship with a drill that others twirl lower down with a strap held at both<br />

ends, and so keep the drill continuously moving. We took the red-hot<br />

stake and twisted it round and round like that in his eye, and the blood<br />

poured out despite the heat. His lids and brows were scorched by flame<br />

from the burning eyeball, and its roots crackled with fire. As a great<br />

axe or adze causes a vast hissing when the smith dips it in cool water to<br />

temper it, strengthening the iron, so his eye hissed against the olivewood<br />

stake. Then he screamed, terribly, and the rock echoed. Seized by terror<br />

we shrank back, as he wrenched the stake, wet with blood, from his eye.<br />

He flung it away in frenzy, and called to the Cyclopes, his neighbors who<br />

lived in caves on the windy heights. They heard his cry, and crowding<br />

in from every side they stood by the cave mouth and asked what was<br />

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.<br />

wrong: “Polyphemus, what terrible pain is this that makes you call<br />

through deathless night, and wake us? Is a mortal stealing your flocks,<br />

or trying to kill you by violence or treachery?”<br />

Out of the cave came mighty Polyphemus’ voice: “Nobody, my<br />

friends, is trying to kill me by violence or treachery.”<br />

To this they replied with winged words: “If you are alone, and<br />

nobody does you violence, it’s an inescapable sickness that comes from<br />

Zeus: pray to the Lord Poseidon, our father.”<br />

Bk IX:413–479<br />

Odysseus Tells His Tale: esCape<br />

‘Off they went, while I laughed to myself at how the name and the<br />

clever scheme had deceived him. Meanwhile the Cyclops, groaning<br />

and in pain, groped around and labored to lift the stone from the door.<br />

Then he sat in the entrance, arms outstretched, to catch anyone stealing<br />

past among his sheep. That was how foolish he must have thought I<br />

was. I considered the best way of escaping, and saving myself, and my<br />

men from death. I dreamed up all sorts of tricks and schemes, as a man<br />

will in a life or death matter: it was an evil situation. This was the plan<br />

that seemed best. The rams were fat with thick fleeces, fine large beasts<br />

with deep black wool. These I silently tied together in threes, with<br />

twists of willow on which that lawless monster, Polyphemus, slept. The<br />

middle one was to carry one of my men, with the other two on either<br />

side to protect him. So there was a man to every three sheep. As for me<br />

I took the pick of the flock, and curled below his shaggy belly, gripped<br />

his back and lay there face upwards, patiently gripping his fine fleece<br />

tight in my hands. Then, sighing, we waited for the light.<br />

As soon as rosy-fingered Dawn appeared, the males rushed out to<br />

graze, while the un-milked females udders bursting bleated in the pens.<br />

Their master, tormented by agonies of pain, felt the backs of the sheep<br />

as they passed him, but foolishly failed to see my men tied under the<br />

rams’ bellies. My ram went last, burdened by the weight of his fleece,<br />

and me and my teeming thoughts. And as he felt its back, mighty<br />

Polyphemus spoke to him:<br />

“My fine ram, why leave the cave like this last of the flock? You<br />

have never lagged behind before, always the first to step out proudly<br />

and graze on the tender grass shoots, always first to reach the flowing<br />

river, and first to show your wish to return at evening to the fold. Today<br />

you are last of all. You must surely be grieving over your master’s eye,<br />

blinded by an evil man and his wicked friends, when my wits were<br />

fuddled with wine: Nobody, I say, has not yet escaped death. If you only<br />

My Notes<br />

Activity 1.11<br />

continued<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 37

Activity 1.11<br />

continued<br />

My Notes<br />

The Road of Trials<br />

38 springBoard® english Textual power Level 3<br />

had senses like me, and the power of speech to tell me where he hides<br />

himself from my anger, then I’d strike him down, his brains would be<br />

sprinkled all over the floor of the cave, and my heart would be eased of<br />

the pain that nothing, Nobody, has brought me.”<br />

With this he drove the ram away from him out of doors, and I<br />

loosed myself when the ram was a little way from the cave, then untied<br />

my men. Swiftly, keeping an eye behind us, we shepherded those<br />

long-limbed sheep, rich and fat, down to the ship. And a welcome<br />

sight, indeed, to our dear friends were we, escapees from death, though<br />

they wept and sighed for the others we lost. I would not let them weep<br />

though, but stopped them all with a nod and a frown. I told them<br />

to haul the host of fine-fleeced sheep on board and put to sea. They<br />

boarded swiftly and took their place on the benches then sitting in their<br />

rows struck the grey water with their oars. When we were almost out of<br />

earshot, I shouted to the Cyclops, mocking him: “It seems he was not<br />

such a weakling, then, Cyclops, that man whose friends you meant to<br />

tear apart and eat in your echoing cave. Stubborn brute not shrinking<br />

from murdering your guests in your own house, your evil deeds were<br />

bound for sure to fall on your own head. Zeus and the other gods have<br />

had their revenge on you.”’<br />

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.<br />

After reading<br />

In Embedded Assessment 2, you will be asked to create visual<br />

representations of a text. List six events from the story of the Cyclops<br />

that would be excellent visual representations of the story as a whole.<br />

Writing Prompt: Describe how Odysseus is a heroic figure. In your<br />

response, use words from the Word Wall that describe heroic traits<br />

or qualities. Include specific evidence from the text to support your<br />

assertions.<br />

Activity 1.11<br />

continued<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 39

Activity<br />

1.12<br />

A Different Kind of Heroine<br />

SUGGESTED LEARNING STRATEGIES: Graphic Organizer, Notetaking<br />

It is not typical for an adolescent female to be portrayed as a hero in<br />

literature. As your teacher shows you selected clips from Mulan, note how<br />

Mulan’s imperfections lead ultimately to her glory and the honor of her<br />

family. Take notes on the graphic orgnizer below and on the next page.<br />

Scene<br />

Describe Mulan’s<br />

actions.<br />

1 Mulan attempts to<br />

be perfect but fails<br />

when the cricket<br />

jumps on the<br />

matchmaker.<br />

2<br />

3<br />

How does Mulan<br />

feel about herself?<br />

Mulan feels she<br />

has failed and<br />

dishonored her<br />

family.<br />

40 SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

How do others feel<br />

about Mulan?<br />

Others feel Mulan<br />

is a disgrace.<br />

Explain which<br />

stage in the hero’s<br />

journey this scene<br />

reflects.<br />

This scene may<br />

represent a call to<br />

adventure because<br />

it drives Mulan to<br />

honor her family.<br />

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. All rights reserved.<br />

4<br />

5<br />

Writing Prompt: Write a thesis statement explaining whether Mulan’s<br />

faults help her to become a hero or hinder her. Then, write two to four<br />

sentences that support your thesis statement with evidence from the film.<br />

Activity 1.12<br />

continued<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 41

Activity<br />

1.13<br />

Your teacher will assign you specific paragraphs of the article “Woman<br />

Warrior” to read. Highlight important information, and take notes in<br />

the My Notes section to become the expert on those paragraphs. Then,<br />

on this page, summarize the information you decide is most important.<br />

Remember to put the information in your own words. You will then<br />

join a group who has not read your paragraphs, and it will be your<br />

responsibility to teach them your information. They will, in turn, teach<br />

you the parts that you did not read.<br />

Paragraphs assigned:<br />

Summary:<br />

Creating a Different Kind of Heroine<br />

SUGGESTED LEaRNiNG STRaTEGiES: Notetaking, Summarizing,<br />

visualizing<br />

42 SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.<br />

Take notes below on the information you learn from your classmates<br />

(you may leave the paragraphs you read blank).<br />

Paragraphs:<br />

2 3<br />

4 5<br />

6 7<br />

8 9<br />

Now read the article on your own. On a separate paper, combine the<br />

most important information from each paragraph into a summary of the<br />

entire article.<br />

Activity 1.13<br />

continued<br />

<strong>Unit</strong> 1 • The Challenge of Heroism 43

Activity 1.13<br />

continued<br />

Creating a Different Kind of Heroine<br />

My Notes A r t i c l e<br />

Woman Warrior<br />

&<br />

Grammar UsaGe<br />

an appositive is a noun<br />

or noun phrase that gives<br />

further detail or explanation<br />

of the noun next to it. When<br />

an appositive appears in<br />

the middle of a sentence,<br />

it is usually surrounded by<br />

commas.<br />

Example: “Meanwhile,<br />

children’s book author<br />

Robert San Souci, a<br />

frequent Disney consultant,<br />

had suggested that a<br />

Chinese poem called ‘The<br />

Song of Fa Mu Lan’ might<br />

make a good movie.”<br />

44 SpringBoard® English Textual Power Level 3<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

by Corie Brown and Laura Shapiro<br />

Way off in the distance, barely visible behind a snowy mountain<br />

range, a million or so raging Huns are bearing down on a brave<br />

little battalion trying to defend China. The frightened Chinese<br />

soldiers draw their swords and prepare to die, nobly if possible.<br />

But a misfit soldier named Ping suddenly gets an idea and rushes<br />

to fire a cannon at a distant peak. Sure enough, the blast sets off an<br />

avalanche and the Huns are buried, at least temporarily. “You’re the<br />

man!” says Ping’s sidekick admiringly. But, glory hallelujah, she<br />

isn’t.<br />

Ping is really a girl named Mulan, and “Mulan” is the first<br />

Disney animated feature to revamp the hardiest conventions of the<br />

genre, leaving such chirpy predecessors as “The Little Mermaid”<br />

and “Beauty and the Beast” in the dust. Based on a Chinese legend,<br />

“Mulan” tells of a girl who’s a failure at all the maidenly arts,<br />

especially husband hunting. When the emperor drafts her father<br />

into the Army despite his poor health, she determines to go in his<br />

place. She cuts her hair, runs off with his armor and sword and ends<br />

up saving China. But the plot isn’t what sets “Mulan” apart — it’s<br />

the character. She doesn’t look like a Barbie doll, she doesn’t dream<br />

about a prince and she certainly doesn’t hang around waiting to be<br />

rescued. The conflict that drives her is about honor, not romance:<br />

how can she be a dutiful Chinese daughter and still be true to<br />

herself? In the most radical twist of all, Mulan doesn’t rely on magic<br />

to solve her problems. She sweats her way through basic training<br />

until she gets good and strong, and when she faces an enemy too<br />

big to fight she outsmarts him. Love? Just at the very end. And it’s<br />

he, not she, who has some waking up to do.<br />

“Mulan” wasn’t supposed to turn out this way. The movie<br />

originated nearly a decade ago as a dimwitted short called “China<br />

Doll,” meant to go directly to video without stopping in theaters.<br />

It was about a miserable Chinese girl who struggles against<br />

oppression until a British Prince Charming whisks her away to<br />

happiness in the West. None of Disney’s first-string animators<br />

would have anything to do with it. But before it could be produced,<br />

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.

© 2010 College Board. all rights reserved.<br />

“Beauty and the Beast” came out and made box-office history as the<br />

first animated feature since “Snow White” to draw audiences of all<br />

ages. Disney promptly scoured the studio for more such projects,<br />

even “China Doll.” Meanwhile, children’s book author Robert San<br />

Souci, a frequent Disney consultant, had suggested that a Chinese<br />

poem called “The Song of Fa Mu Lan” might make a good movie.<br />

So the “China Doll” team, now the “Mulan” team, began trying to<br />

patch together the two Chinese tales. “Mulan started out in the<br />

groove of Belle and Mermaid, with a ton of attitude,” says Chris<br />

Sanders, story editor on “Mulan.” “The whole point of the first draft<br />

was for Mulan to get the guy.”<br />

What saved “Mulan” was its lack of studio status. Everyone on<br />

the team came from the lower rungs of Disney’s hierarchy. Barry<br />