The Gaucho and Argentine Identity

The Gaucho and Argentine Identity

The Gaucho and Argentine Identity

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

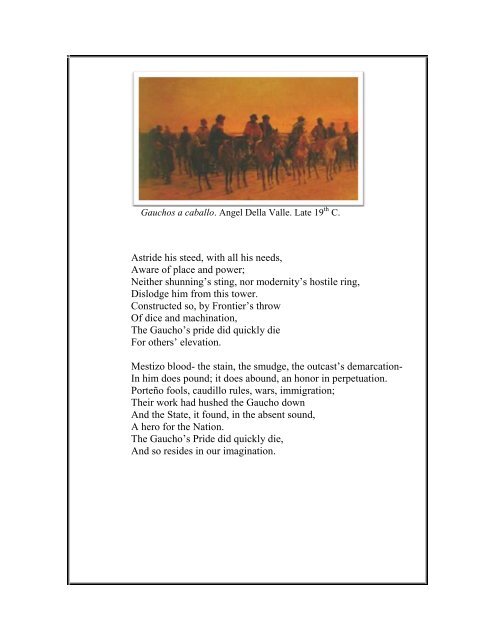

<strong>Gaucho</strong>s a caballo. Angel Della Valle. Late 19 th C.<br />

Astride his steed, with all his needs,<br />

Aware of place <strong>and</strong> power;<br />

Neither shunning’s sting, nor modernity’s hostile ring,<br />

Dislodge him from this tower.<br />

Constructed so, by Frontier’s throw<br />

Of dice <strong>and</strong> machination,<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Gaucho</strong>’s pride did quickly die<br />

For others’ elevation.<br />

Mestizo blood- the stain, the smudge, the outcast’s demarcation-<br />

In him does pound; it does abound, an honor in perpetuation.<br />

Porteño fools, caudillo rules, wars, immigration;<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir work had hushed the <strong>Gaucho</strong> down<br />

And the State, it found, in the absent sound,<br />

A hero for the Nation.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Gaucho</strong>’s Pride did quickly die,<br />

And so resides in our imagination.

Liam McGinty<br />

HIST 388<br />

03/11/12<br />

Prof. Walker<br />

THE GAUCHO AND ARGENTINE IDENTITY<br />

Few images are as iconic as this: the emboldened, mounted rider galloping across<br />

endless terrain, unbounded by geography, authority, worry; it is an image of a truly<br />

independent, uncomplicated life. From the tip of Chile to the Canadian Plains one can<br />

find him: the cowboy, vaquero, huaso, llanero. Yet nowhere has he become so powerful,<br />

so essential to national identity, than in Argentina’s gaucho. In culture high <strong>and</strong> low, in<br />

rural tavern <strong>and</strong> urban literary club, the gaucho has come to form a core part of<br />

Argentidad or ‘<strong>Argentine</strong>-ness’, being at once both the most authentic <strong>and</strong> most ethereal<br />

of national icons.<br />

This essay is an survey of that status, examining gauchos in three specific, semi-<br />

chronological ways. First, the gauchos’ origins, formation, <strong>and</strong> customs will be<br />

elucidated, focusing on an intense equestrianism <strong>and</strong> animal- oriented identity. Second,<br />

their role as distinct political actors in 19 th Century <strong>Argentine</strong> history will be presented,<br />

showing a declining economic relevance amongst increasing societal change. Finally,<br />

literary representations by both <strong>Argentine</strong>s <strong>and</strong> European immigrants will demonstrate<br />

how, through a nationalistic historical appropriation, the contemptible gaucho became a<br />

coveted part of <strong>Argentine</strong> identity.<br />

For most of its history as a colony of Spain, the region that is now Argentina was<br />

of little importance. <strong>The</strong> opulence at h<strong>and</strong> in Peru <strong>and</strong> Mexico cast a shadow on the rest<br />

of Spain’s possessions, diverting men <strong>and</strong> money to more prosperous regions. This<br />

neglect was important, for it allowed, uninterrupted, a natural increase of semi-wild cattle

<strong>and</strong> horses to occur atop an immense, 620 mile wide, flat, grassy plain; the pampas 1 .It<br />

was only in the late 1776, with a growing Portuguese threat from the north, that Buenos<br />

Aires received a Vice Royal 2 . Thus marks the beginning of a roughly 100- year span of<br />

time from which gaucho culture <strong>and</strong> legend emerged 3 .<br />

<strong>The</strong> base of this culture was the horse; its economic basis, the cow. <strong>The</strong> sheer<br />

vastness of the treeless pampas made horses the primary form of transportation; walking<br />

would get one nowhere, <strong>and</strong> so “man became equestrian” 4 . <strong>The</strong> ubiquity of cattle meant<br />

an abundant food supply, such that it became “possible to survive on the pampa without<br />

work <strong>and</strong> with relative comfort” 5 , leading to an feeling of independence <strong>and</strong> self-reliance.<br />

And though cattle would soon come to play a growing economic role, it was the horse<br />

that truly makes gaucho culture.<br />

Usually with the “hardy compact creole horse 6 ” as partner, together they formed<br />

a “half man half horse” 7 . It is impossible to imagine the gaucho horseless; without it, he<br />

simply doesn’t exist. Cattle may have been the fuel for the gaucho, but the horse was the<br />

engine, the vehicle that granted freedom <strong>and</strong> dignity. <strong>Gaucho</strong>s were notorious for their<br />

“determination to prefer all tasks on horseback” 8 , including making butter, fishing,<br />

bathing <strong>and</strong> drawing water from a well 9 . Developing <strong>and</strong> maintaining horse- riding skills<br />

1<br />

Richard W. Slatta, <strong>Gaucho</strong>s <strong>and</strong> the Vanishing Frontier (Lincoln: University of<br />

Nebraska, 1983). Pg. 17.<br />

2<br />

Gabriela Nouzeilles <strong>and</strong> Graciela Montaldo, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Argentine</strong> Reader: History, Culture,<br />

Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002). Pg. 38.<br />

3<br />

Madaline Willis Nichols, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gaucho</strong> (Durham: Duke University Press, 1942). Pg. 3<br />

4 Ibid, Pg.3.<br />

5 Ibid, Pg.17.<br />

6 Slatta- Pg 28.<br />

7 Ibid, Pg.9.<br />

8 Ibid, Pg.26.<br />

9 Nichols- Pg. 19.

was of paramount importance, with games such as pialar even practicing falling off,<br />

teaching how to l<strong>and</strong> correctly 10 . It was said they “ranked their horses above women” 11 ,<br />

whose experiences have been, unfortunately, marginalized in such a masculine mythos.<br />

As the horse meant mobility, thus did the accoutrements of the gaucho lifestyle<br />

develop; the gaucho carried everything he needed with him. His recado saddle was soft,<br />

<strong>and</strong> used for sleeping, his facon (knife) could kill <strong>and</strong> skin, along with the more primitive<br />

bola thrown at wild rheas. Almost everything he owned was obtained from horses <strong>and</strong><br />

cattle, <strong>and</strong> there was plenty to obtain 12 . Simply cooked meat on an open fire, asado, was<br />

his food, the yerba maté his drink. Being neither Spanish nor Indian, the gaucho<br />

presented an autochthonous development 13 , though many argue for an essentially Iberian<br />

origin 14 . <strong>Gaucho</strong>s are most accurately viewed as a cultural group with a mixed-race<br />

mestizo core.<br />

At any rate, these horsemen, so clearly well adapted to their environment, bursts<br />

into history as the gaucho because of the peculiar political economy of late 18 th Century<br />

Latin America. <strong>The</strong> region being so poor, cattle hides were the only valuable commodity,<br />

yet colonial Spanish regulations prevented their direct export, leading to a cross-national<br />

contrab<strong>and</strong> culture in which, along with cattle hunting in the unpropertied pampas, “the<br />

gaucho was the means whereby the community received the goods it needed” 15 . Thus,<br />

10<br />

Slatta- Pg. 81.<br />

11<br />

E. Tinker, "<strong>The</strong> Horsemen of the Americas," Hispanic American Historical Review,<br />

1962: 191-198. Pg. 192.<br />

12<br />

Slatta- Pg. 72.<br />

13<br />

Slatta- Pg.9.<br />

14<br />

Charles Julian Bishko, "<strong>The</strong> Peninsular Background of Latin American Cattle<br />

Ranching," Hispanic American Historical Review 32, no. 4 (Nov 1952): 491-515.<br />

15<br />

Nichols- Pg. 37.

gauchos were a necessary part of the economy, but they also had an outlaw’s taint about<br />

them.<br />

This status changed when frustration at continued economic stagnancy helped<br />

mobilize support for independence; a tenuous <strong>Argentine</strong> identity was forming, <strong>and</strong> for it<br />

to survive it needed a skill-set only gauchos could provide. <strong>The</strong> resulting wars of<br />

independence during the 1810s expelled the Spanish, but they opened a long, brutal<br />

process of intra-American struggle over borders, ideology, <strong>and</strong> the future; what kind of<br />

nation was Argentina going to be? <strong>Gaucho</strong>s had sprung form a specific place <strong>and</strong> time,<br />

<strong>and</strong> both were changing rapidly. A roving, battle- hardened b<strong>and</strong>itti untethered from the<br />

formal economy did not bode well for future stability.<br />

In a short time, the political differences within Argentina found expression in two<br />

distinct groupings, the Federalists <strong>and</strong> the Unitarians. Federalists believed in a federal<br />

system with strong state governments. <strong>The</strong>ir base was rural, with a traditional patron-<br />

client paternalism not wholly in tune with the republican spirit of the times. Opposing<br />

them were the urban- based Unitarians, who sought a strong centralizing government<br />

bent on modernization <strong>and</strong> development.<br />

At first, the Federalists were dominant, with Juan Manuel de Rosas acting as<br />

dictator from 1835, partly by disciplining the “rootless <strong>and</strong> marginal lower classes,<br />

thereby transforming…peons into political followers” 16 - gauchos. As modernity<br />

encroached upon the pampa, <strong>and</strong> the hunting, hide <strong>and</strong> contrab<strong>and</strong> economy gave way, a<br />

core aspect of gaucho identity began to suffer, that of unlimited mobility. <strong>The</strong> freedom of<br />

16 Ariel de la Fuente, Children of Facundo: Caudillo <strong>and</strong> <strong>Gaucho</strong> Insurgency During the<br />

<strong>Argentine</strong> State Formation Process (La Rioja 1853-1870) (Durham: Duke University<br />

Press, 2000). Pg. 3.

the pampas was disappearing, <strong>and</strong> it is a core paradox of <strong>Argentine</strong> history that the very<br />

forces of reaction that abetted this process, the rural caudillo oligarchy as personifies by<br />

Rosas, were the same forces to which the gaucho class gave its loyalty. Increasing<br />

“political, military, <strong>and</strong> legal restrictions” 17 , such as forced conscription <strong>and</strong> harsh<br />

vagrancy laws, combined with economic competition from increased sheep farming 18 ,<br />

had a devastating impact on gaucho culture. Rarely has the gap between romantic ideal<br />

<strong>and</strong> harsh reality been so great.<br />

So why did gauchos behave they way they did, eagerly following charismatic<br />

caudillos to war? Defining caudillismo as a “social system in which groups of patrons<br />

<strong>and</strong> clients use violence to compete for power <strong>and</strong> wealth” 19 , such relations actually<br />

provided many gauchos with material goods otherwise unobtainable in the shrinking hide<br />

economy of old 20 . Further, caudillos, numerous provincialists that they were, shared<br />

bonds of identity with gauchos far closer than that of a distant, cold state, a state whose<br />

policies would not have treated gauchos any better. Unitarians had a far less nuanced<br />

explanation.<br />

Writing in Chilean exile, Domingo Sarmiento published a work that vaulted the<br />

gaucho to the forefront of <strong>Argentine</strong> identity. Entitled Facundo: Civilization <strong>and</strong><br />

Barbarism (1845), the work is dividing line in <strong>Argentine</strong> history <strong>and</strong> historiography.<br />

Sarmiento envisioned “two distinct civilizations…on <strong>Argentine</strong> soil: one… reproducing<br />

the naïve popular effects of the Middle Ages; the other, ignoring what lies at its feet, is<br />

17 Slatta- Pg. 111.<br />

18 Ibid. Pg. 141.<br />

19 Fuente- Pg.3.<br />

20 Ibid. Pg. 189.

attempting to duplicate the latest achievements of European civilization.” 21 For<br />

Sarmiento, the root cause of this distinction was the gaucho, “who has developed<br />

physical qualities…without any corresponding intellectual ones” 22 . <strong>The</strong> gaucho was the<br />

result of a “physical environment, Spanish tradition, <strong>and</strong> mixed blood” 23 retarding<br />

<strong>Argentine</strong> development. Only the “transforming value of trade, immigration, education,<br />

<strong>and</strong> democratic institutions” 24 could guaranteed Argentina’s future, <strong>and</strong> so the gaucho<br />

had to go.<br />

Sarmiento’s vision won out; the Rosas dictatorship fell in 1852, <strong>and</strong> Sarmiento<br />

himself became President in 1868. <strong>The</strong> rush to develop Argentina began with vigor.<br />

Immigrants from Europe, especially Spain <strong>and</strong> Italy, flooded in. <strong>The</strong> resulting population<br />

boom lowered labor costs. Sheep rearing for wool crowded out cattle, while fencing<br />

“facilitated l<strong>and</strong> consolidation….<strong>and</strong> farming” 25 . Railroads were built, refrigeration was<br />

made industrially viable; new breeds of cattle, sheep, <strong>and</strong> horses crowded out the old<br />

criollos. 26 All of these changes made gaucho culture obsolete.<br />

And then, a poem was written. Book length, with a structured rhyming scheme,<br />

the two- part <strong>Gaucho</strong> Martin Fierro (1872) tells a bitter story of injustice at the h<strong>and</strong>s of<br />

“arbitrary <strong>and</strong> cruel state officials” 27 . In a rich, genuine gaucho prose, the author Jose<br />

21<br />

Domingo Sarmiento, A Sarmiento Anthology (Princeton: Princeton University Press,<br />

1948). Pg. 131.<br />

22<br />

Ibid. Pg. 117.<br />

23<br />

Joseph T. Criscenti, Sarmiento <strong>and</strong> His Argentina (Boulder: Lynne Rienne Publishers,<br />

1993). Nicholas Shumway: Sarmiento <strong>and</strong> the Narrative of Failure. Pg. 52.<br />

24<br />

Joseph T. Criscenti, Sarmiento <strong>and</strong> His Argentina (Boulder: Lynne Rienne Publishers,<br />

1993). Pg. 3.<br />

25<br />

Slatta- Pg. 141.<br />

26<br />

Ibid. Pg. 143.<br />

27<br />

Gabriela Nouzeilles <strong>and</strong> Graciela Montaldo, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Argentine</strong> Reader: History, Culture,<br />

Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002). Pg. 133.

Hern<strong>and</strong>ez idealizes the old life of gaucho freedom, ringing out as an indictment against<br />

its cultural defenestration. Several excerpts demonstrate its power…<br />

I am a gaucho, <strong>and</strong> take this from me<br />

As my tongue explains to you:<br />

For me the earth is a small place<br />

And it could well be bigger-<br />

<strong>The</strong> snake does not bite me<br />

Nor the sun burn my brow. 28<br />

…..<br />

It is my glory to live as free<br />

As a bird in the sky:<br />

I make no nest on this ground<br />

Where there’s so much to be suffered,<br />

And no one will follow me<br />

When I take to flight again. 29<br />

…..<br />

And listen to the story told<br />

By a gaucho who’s hunted by the law;<br />

Who’s been a father <strong>and</strong> husb<strong>and</strong><br />

Hard- working <strong>and</strong> willing-<br />

And in spite of that, people take him<br />

To be a criminal. 30<br />

…..<br />

And sitting beside the fire<br />

Waiting for day to come,<br />

He’d suck at the bitter mate<br />

Till he was glowing warm,<br />

While his girl was sleeping<br />

Tucked up in his poncho. 31<br />

<strong>The</strong> descriptions of being part of one’s surroundings, of free movement, injustice,<br />

<strong>and</strong> simple physical pleasure create a palpable sense of nostalgia. It was effective. <strong>The</strong><br />

gaucho’s denouement had gone too far; his resurrection in literary form had begun. <strong>The</strong><br />

causes for the poem’s popularity are many, but one st<strong>and</strong>s out above all others,<br />

immigration. <strong>The</strong> rush to Europeanize, to jettison all that was American, created an<br />

28 Jose Hern<strong>and</strong>ez, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gaucho</strong> Martin Fierro, trans. C.E. Ward (New York: State<br />

University of New York Press, 1967). Pg. 9<br />

29 Ibid. Pg.9<br />

30 Ibid. Pg. 11.<br />

31 Ibid. Pg. 13.

existential crisis for many. Europeans without a strong <strong>Argentine</strong> identity to assimilate to<br />

might not grow into the nation. A nationalist impulse was about the place, connected to<br />

the soil <strong>and</strong> tradition, celebrating the spurned, populist in sentiment, <strong>and</strong> weary of<br />

unceasing change. As one author states, the gaucho “was coming to signify a proud<br />

cultural identity applicable to anything native to the <strong>Argentine</strong>, Uruguayan, or Rio<br />

Gr<strong>and</strong>ense countryside, an identity particularly defined by clothing, speech, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

habits <strong>and</strong> skills of rural life” 32 . Another, Tavia Quaid, states “the monomania for<br />

imitation” 33 of Europe had stirred something in <strong>Argentine</strong> souls, a search for who they<br />

were, <strong>and</strong> that in the gaucho Hern<strong>and</strong>ez had found “those character traits that establish a<br />

national personification” 34 . At the same time, the work is a “lamentation of ultimate<br />

submission” 35 , perhaps echoing a now cliché Latin American fatalism.<br />

Though the dark side to such nationalist rhetoric is often a demonization of the<br />

foreigner, <strong>and</strong> a concomitant glorification of anti-democratic, reactionary traditions, two<br />

immigrant authors of nationalist bent provide an interesting way to explore how a<br />

traditionalist iconography was adopted to propagate universal notions of freedom,<br />

allowing a “close interaction <strong>and</strong> mutual cultural modification between immigrants <strong>and</strong><br />

gauchos” 36 .<br />

First, Alberto Gerchunoff’s Jewish <strong>Gaucho</strong>s of the Pampas (1910), a series of<br />

fictionalized accounts of Jewish-<strong>Gaucho</strong> interactions, shows an acceptance of the gaucho<br />

32<br />

John Charles Chasteen, Heroes on Horseback: A Life <strong>and</strong> Times of the Last <strong>Gaucho</strong>s<br />

Caudillos (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995). Pg. 120.<br />

33<br />

Tavia Quaid, American Frontiers: Historical <strong>and</strong> Literary Representations of <strong>Gaucho</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> Cowboys (Reed College, 2006). Pg. 17<br />

34<br />

Ibid. Pg. 19.<br />

35<br />

Ibid. Pg. 3.<br />

36<br />

Ariana Huberman, <strong>Gaucho</strong>s <strong>and</strong> Foreigners: Glossing Culture <strong>and</strong> <strong>Identity</strong> in the<br />

<strong>Argentine</strong> Countryside (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2011). Pg.4.

as authentically <strong>Argentine</strong>; “the native gaucho represents <strong>Argentine</strong> nationality for the<br />

newly arrived population” 37 . <strong>Gaucho</strong>s are not seen as menacing civilization, but rather a<br />

“conquered people” who are “full of vigor, instinctual freedom, <strong>and</strong> generosity” 38 . One<br />

story, <strong>The</strong> Herdsman, tells of gaucho who kills his own for retreating from a fight,<br />

representative of “a people who had worked so hard on these plains <strong>and</strong> who forgave all<br />

sins but cowardice” 39 . Of note here is Gerchunoff’s own nationalism, Zionism, looking<br />

admirably at a distant identity, aiding its definition of the authentic <strong>Argentine</strong> as gaucho.<br />

Second, Edmundo Murray examines several works by Irish immigrants in turn of<br />

the century Argentina. Most are desirous to look down on swarthy <strong>Argentine</strong>s of<br />

uncertain race, eager to exploit their assigned British identities for social acceptance <strong>and</strong><br />

financial gain. Yet one sticks out from the rest, William Bulfin. Author of Tales of the<br />

Pampas (1900), Bulfin’s collection of short stories portrays the gaucho positively, <strong>and</strong><br />

“with an insight that few gringos have equaled” 40 <strong>and</strong> a “profound knowledge of the lives<br />

of <strong>Argentine</strong> gauchos” 41 . Based on his experiences as a ranch h<strong>and</strong>, Bulfin leans “toward<br />

admiration of the gauchos, <strong>and</strong> dislike of the English” 42 , seeing himself in the former <strong>and</strong><br />

urban, European <strong>Argentine</strong> elites in the later. Also unlike most Irish immigrants in<br />

Argentina, Bulfin had embraced the emerging separatist Irish nationalism of the era.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se two admiring representations of the gaucho by nationalist, European authors<br />

37 Ibid. Pg. 112.<br />

38 Ibid. Pg. 113.<br />

39 Alberto Gerchunoff, <strong>The</strong> Jewish <strong>Gaucho</strong> of the Pampas, trans. Prudencio de Pereda<br />

(Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998). Pg. 70.<br />

40 Edmundo Murray, Becoming <strong>Gaucho</strong> Ingleses: Diasporic Models in Irish-<strong>Argentine</strong><br />

Literature (Palo Alto: Academica Press, Maunsel <strong>and</strong> Company, 2009). Pg. 85<br />

41 Graciela Obert, Una vision irl<strong>and</strong>esa de las pampas argentinas en Tales of the<br />

Pampas, - -, 2009, www.biblioteca.unlpam.edu.ar/pubpdf/anuario_fch/n09a19obert.pdf<br />

(accessed Feb 20, 2012). Pg. 275. Author’s translation.<br />

42 Murray- Pg. 98.

indicate an acceptance of <strong>and</strong> respect for a uniquely <strong>Argentine</strong> gaucho identity, bolstering<br />

its idealization to the world at large, <strong>and</strong> continuing its<br />

Murray wrote that “the invention of history is a process intimately related with the<br />

construction of popular narratives” 43 , <strong>and</strong> in this vein the gaucho is surely an invention,<br />

yet one grounded in historical truth. <strong>The</strong> external symbols of gauchos are everywhere, in<br />

urban maté drinkers, asado lovers, but also in the deep sentiment that from the vast<br />

pampas came forth not a mere construct but a real, new person, <strong>and</strong> a new culture,<br />

something distinct. <strong>The</strong> half man half horse still rides out.<br />

To conclude, a return to the cover painting is needed. Located in the Museo<br />

Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires, <strong>Gaucho</strong>s a caballo demonstrates several<br />

<strong>Gaucho</strong> traits discussed above. Painted by the Italian-<strong>Argentine</strong> Angel Della Valle, the<br />

work displays a nobility in the <strong>Gaucho</strong>s’ posture, along with a fluidity between<br />

themselves <strong>and</strong> their horses. <strong>The</strong> tone <strong>and</strong> color, however, is foreboding, conspiratorial,<br />

infused with a cautionary romanticism. It is hard to determine if it is sunrise or sunset, or<br />

for what purpose they have gathered. A sense of unease, of threat, permeates the painting,<br />

yet dignity too. Indeed, so strong is the gauchos’ presence, it is as if, had they not been<br />

real, someone would have invented them. And, in a way, they did.<br />

43 Ibid. Pg. 110.