PowerPoint Slides - American Bar Association

PowerPoint Slides - American Bar Association

PowerPoint Slides - American Bar Association

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Milbank<br />

ABA IPL MEETING,<br />

JUNE 16-20, 2004 TORONTO, ONTARIO<br />

DEVELOPMENTS IN INTELLECTUAL<br />

PROPERTY<br />

A UNITED KINGDOM PERSPECTIVE<br />

Presented by James Tumbridge<br />

London<br />

Frankfurt<br />

New York<br />

Los Angeles<br />

Palo Alto<br />

Washington, D.C.<br />

Tokyo<br />

Hong Kong<br />

Singapore<br />

Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy

MILBANK<br />

ABA IPL MEETING,<br />

JUNE 16-20, 2004 TORONTO, ONTARIO<br />

DEVELOPMENTS IN INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY<br />

A UNITED KINGDOM PERSPECTIVE<br />

Presented by James Tumbridge<br />

LN1:#20078011v2

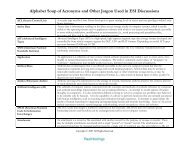

This documents aims to give a skeleton overview of four trade mark cases which have<br />

clarified English & European law.<br />

Topic:<br />

• Trade Marks<br />

LN1:#20078011v2<br />

o Reed v Reed [2004] EWCA Civ 159 – A review of Trade Mark<br />

Infringment – Likelihood of Confusion – Own name Defence – Internet<br />

uses such as Pop up Banners & Metatags<br />

o Henkel KGaA v OHIM conjoined cases C-456/01P & C-457/01P –<br />

Community Trade Marks – Shape & Colour<br />

o Eli Lilly & Co. case R 120/2001-2 – Community Trade Mark – Taste<br />

o Shield Mark BV v Joost Kist h.o.d.n. Memex case C-283/01 –<br />

Community Trade Mark – A Sound Mark

Reed v Reed [2004] EWCA Civ 159<br />

The appellants were three companies of a multinational publishing group, known<br />

collectively in the appeal as RBI. RBI had for many years published a wide variety of<br />

business magazines and journals, which carried amongst other items advertisements for<br />

jobs. Some adverts were placed by would be employers and others by employment<br />

agencies.<br />

The respondents known collectively as Reed Employment had their beginning in 1960,<br />

when Mr. Alec Reed founded the now well known employment agency of ‘Reed.’ Since<br />

that time they have become familiar sights in every town across the UK and are one of<br />

the most recognised employment agencies.<br />

Reed Employment registered the trade mark in suit in 1986, shortly after registrations<br />

for services became possible in the UK. The mark is ‘Reed’ registered for employment<br />

agency services in Class 35.<br />

Class 35 which accords with the Internationally Recognised Classification of the Nice<br />

Treaty covers; ‘Advertising, business management, business administration and office<br />

functions.’ This covered the activities of both parties.<br />

In 1995 Reed Employment began to use the internet as a business tool with<br />

www.reed.co.uk. The advertisements like the traditional paper ones did not specify the<br />

would be employer. This accorded with Reed Employment’s long policy of selectively<br />

putting would be employees and employers in contact.<br />

In 1999 RBI decided to expand their job-related advertisements and launched<br />

www.totaljobs.com. The first version gave way to steadily more advanced versions. The<br />

website included amongst other items logos of the appellants such as; Reed Business<br />

Information & DESIGN, and Reed Elsevier & DESIGN.<br />

LN1:#20078011v2

All versions of the www.totaljobs.com website were alleged by Reed Employment to<br />

infringe their trade mark and constitute passing off. The judge at first instance found<br />

both and held for Reed Employment.<br />

The unanimous decision of the Court of Appeal led by Lord Justice Jacob reversed the<br />

findings of Mr. Justice Pumfrey at first instance and reviewed the interpretation of the<br />

European law behind the UK Trade Marks Act.<br />

The relevant EU provisions were:<br />

Article 5 - Rights conferred by a trade mark<br />

1. The registered trade mark shall confer on the proprietor exclusive rights therein.<br />

The proprietor shall be entitled to prevent all third parties not having his consent<br />

from using in the course of trade:<br />

LN1:#20078011v2<br />

a. any sign which is identical with the trade mark in relation to goods or<br />

services which are identical with those for which the trade mark is<br />

registered;<br />

b. any sign where, because of its identity with, or similarity to, the trade<br />

mark and the identity or similarity of the goods or services covered by the<br />

trade mark and the sign, there exists a likelihood of confusion on the part<br />

of the public, which includes the likelihood of association between the<br />

sign and the trade mark.<br />

2. Any Member State may also provide that the proprietor shall be entitled to<br />

prevent all third parties not having his consent from using in the course of trade<br />

any sign which is identical with, or similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods<br />

or services which are not similar to those for which the trade mark is registered,<br />

where the latter has a reputation in the Member State and where use of that sign<br />

without due cause takes unfair advantage of, or is detrimental to, the distinctive<br />

character or the repute of the trade mark.<br />

3. The following, inter alia, may be prohibited under paragraphs 1 and 2:<br />

a. affixing the sign to the goods or to the packaging thereof;<br />

b. offering the goods, or putting them on the market or stocking them for<br />

these purposes under that sign, or offering or supplying services<br />

thereunder;<br />

c. importing or exporting the goods under the sign;<br />

d. using the sign on business papers and in advertising.<br />

4. Where, under the law of the Member State, the use of a sign under the conditions<br />

referred to in 1 (b) or 2 could not be prohibited before the date on which the

LN1:#20078011v2<br />

provisions necessary to comply with this Directive entered into force in the<br />

Member State concerned, the rights conferred by the trade mark may not be relied<br />

on to prevent the continued use of the sign.<br />

5. Paragraphs 1 to 4 shall not affect provisions in any Member State relating to the<br />

protection against the use of a sign other than for the purposes of distinguishing<br />

goods or services, where use of that sign without due cause takes unfair advantage<br />

of, or is detrimental to, the distinctive character or the repute of the trade mark.<br />

Article 6 - Limitation of the effects of a trade mark<br />

1. The trade mark shall not entitle the proprietor to prohibit a third party from<br />

using, in the course of trade,<br />

a. his own name or address;<br />

b. indications concerning the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value,<br />

geographical origin, the time of production of goods or of rendering of the<br />

service, or other characteristics of goods or services;<br />

c. the trade mark where it is necessary to indicate the intended purpose of a<br />

product or service, in particular as accessories or spare parts; provided he<br />

uses them in accordance with honest practices in industrial or commercial<br />

matters<br />

2. The trade mark shall not entitle the proprietor to prohibit a third party from<br />

using, in the course of trade, an earlier right which only applies in a particular<br />

locality if that right is recognised by the laws of the Member State in question<br />

and within the limits of the territory in which it is recognised.<br />

The Court of Appeal held:<br />

• RBI’s marks were not identical to Reed Employment, but merely similar. The<br />

Court considered the requirements for a finding of identity by reference to Article<br />

5 (1) (a) of the Trade Marks Directive, and held there is a requirement for aural<br />

and visual identity. The addition of ‘Elsevier’ to ‘Reed’ made a difference, as did,<br />

the addition of ‘Business Information.’ The Court deciding that such additions<br />

would not go unnoticed by the consumer.<br />

• Lord Justice Jacob wished to make clear that additions to the mark can take a case<br />

outside of being ‘identity’ [identical]. He considered it in the light of words<br />

qualifying each other, his example was that ‘Harry’ qualifies ‘Potter’ and vice<br />

versa. His Lordship drew attention to the ECJ’s move away from the UK’s old<br />

rigid view of such matters.<br />

• The services of RBI and Reed Employment were not identical. RBI only<br />

provided job advertisements and Reed Employment provided employment

LN1:#20078011v2<br />

agency services. Lord Justice Jacob distinguished the two by the selectivity<br />

involved in matching parties, and the lack thereof in straight forward<br />

advertisements of jobs.<br />

• Article 5 (1) (b) (infringement: likelihood of confusion) was reviewed and the<br />

Court held that the test involved assuming that the trade mark owner made ‘fair<br />

and notional use’ of its mark across the full scope of the specification. The<br />

comparison is not a straight forward mark for sign comparison. The Court then<br />

must make an assessment as to whether a ‘substantial proportion’ of the relevant<br />

consumers are likely to be confused. Whilst there is a greater likelihood of<br />

confusion with very distinctive marks, where a mark is largely descriptive ‘small<br />

differences’ may suffice to avoid confusion. The ordinary consumer (ECJ calls<br />

them average consumers) is the person to be considered and they will be alert for<br />

differences in largely descriptive marks, such as common surnames. It would be<br />

more difficult to establish a likelihood of confusion for similar descriptive marks.<br />

• The Own Name Defence in Article 6 (1) (a) was held to be available to<br />

companies, such as RBI. However, Lord Justice Jacob reiterated that this defence<br />

remains very limited. The use of a person’s own name was in accordance with<br />

honest practices in industrial or commercial matters, even if there is some actual<br />

confusion between the respective marks. The Court held that there would need to<br />

be significant actual deception to take a trader outside honest practices. The test is<br />

objective; has the defendant in fact caused significant deception, even if<br />

innocently.<br />

• Pop-up Banners; the Court held they did not infringe. The Court considered webusing<br />

members of the public know that all sorts of banners appear when<br />

searching. The Court found that a search under ‘Reed,’ would not make anyone<br />

think that there was a trade connection between the totaljobs.com banner when it<br />

makes no reference to Reed and Reed Employment. There was no likelihood of<br />

confusion established. To establish infringement, once the user clicks through a<br />

banner or link, there must be infringing use on the third party site.<br />

• However, if this had been an Article 5 (1) (a) case (identity of marks and services)<br />

then the Court said the position might have been different. There would be no<br />

need to prove likelihood of confusion. The Court also added that; it may be that<br />

invisible use of this sort is not use in the course of trade, as computers look for<br />

patterns of 0s and 1s and there is no meaning being conveyed to anyone, - no<br />

‘sign.’<br />

• In regard of Metatags, the Court felt the issue was unclear in the pleadings and<br />

grew out of control, however, there was no infringement on Article 5 (1) (b). The<br />

Court considered how metatags work at some length and found that there is no<br />

confusion, as the mere inclusion of a site in a search result does not suggest any<br />

connection with another trader. The Court doubted that under Article 5 (1) (a),<br />

metatag use counted as an indication as to trade origin. Since the computer not a

LN1:#20078011v2<br />

user reads the metatag such use does not count for infringement, these tags never<br />

convey a message to anyone.<br />

• The claim in passing off failed for lack of misrepresentation.<br />

The English Court of Appeal has therefore added much to our understanding of<br />

acceptable use of Trade Marks in the medium of the internet. Of specific note: There is a<br />

difference between the use of a trade mark in a form which users can appreciate and in<br />

the so called ‘invisible forms’ which only a computer can read.

Henkel KGaA v OHIM conjoined cases C-456/01P & C-457/01P<br />

Cases at first instance were T-335/99 and T-336/99<br />

This case was an appeal against a decision of OHIM, the Office of Harmonisation for the<br />

Internal Market (the body which grants Community Trade Marks). The marks in<br />

question were Shape and Colour marks intended primarily for washing machine and dish<br />

washer products. The two marks were known respectively as; ‘rectangular tablet, red &<br />

white,’ and ‘rectangular tablet, green & white.’<br />

Two articles of Council Regulation (EC) No. 40/94 were at issue:<br />

Article 4<br />

‘A Community trade mark may consist of any signs capable of being represented<br />

graphically, particular words, including personal names, designs, letters, numerals, the<br />

shape of goods or of their packaging, provided that such signs are capable of<br />

distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other<br />

undertakings.’<br />

Article 7<br />

LN1:#20078011v2<br />

1. The following shall not be registered:<br />

(a) signs which do not conform to the requirements of Article 4;<br />

(b) trade marks which are devoid of any distinctive character;<br />

(c) trade marks which consist exclusively of signs or indications which<br />

may serve, in trade, to designate the kind, quality, quantity, intended<br />

purpose, value, geographical origin or the time of production of the<br />

goods or of rendering of the service, or other characteristics of the<br />

goods or service; trade marks which consist exclusively of signs or<br />

indications which have become customary in the current language or<br />

in bona fide and established practices of trade;<br />

The OHIM examiner had refused the applications because he considered them ‘devoid of<br />

distinctiveness’ and therefore could not be registered on account of Article 7 (1) (b).<br />

The Board of Appeal stated that a three-dimensional shape had to be sufficiently unique<br />

to imprint itself easily on the mind and stand out from whatever is normal in trade.<br />

The Court of First Instance agreed with this conclusion and refused registration relying<br />

on Article 7 (1) (b).

The European Court of Justice found that Article 4, which permits shape and colour to<br />

constitute Community Trade Marks, required:<br />

1. The Sign Must Be Capable of Distinguishing Goods or Services<br />

2. Of One Undertaking From Those of Other Undertakings.<br />

However, the Court held that being ‘capable of distinguishing’ was not enough; the sign<br />

must have distinctive character.<br />

Distinctive character was to be assessed by a two stage test:<br />

1. By reference to the products or services in respect of which registration has been<br />

applied for, and<br />

2. By reference to the perception of them by the relevant public.<br />

The ECJ further clarified that the more closely the shape for which registration is sought<br />

resembles the shape most likely to be taken by the product in question, the greater the<br />

likelihood of the shape being devoid of any distinctive character for the purposes of<br />

Article 7 (1) (b) of Regulation No. 40/94. Only a Trade Mark which departs significantly<br />

from the norm or customs of the sector and thereby fulfils its essential function of<br />

indicating origin, is not devoid of any distinctive character for the purposes of that<br />

provision.<br />

On a secondary note the ECJ affirmed the Court of First Instance’s sole right to<br />

determine findings of fact and secondly that appeals must rely upon the pleadings of first<br />

instance.<br />

LN1:#20078011v2

Eli Lilly & Co. case R 120/2001-2<br />

The applicant sort to register;<br />

As a gustatory mark for;<br />

LN1:#20078011v2<br />

THE TASTE OF ARTIFICIAL STRAWBERRY FLAVOUR<br />

Class 5 – Pharmaceutical Preparations<br />

The appellant offered a description of the mark only in the following terms; ‘The mark<br />

consists of the taste of strawberry flavour.’<br />

The applicable law was again:<br />

Article 7<br />

1. The following shall not be registered:<br />

(a) signs which do not conform to the requirements of Article 4;<br />

(b) trade marks which are devoid of any distinctive character;<br />

(c) trade marks which consist exclusively of signs or indications which may serve, in<br />

trade, to designate the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value,<br />

geographical origin or the time of production of the goods or of rendering of the<br />

service, or other characteristics of the goods or service; trade marks which consist<br />

exclusively of signs or indications which have become customary in the current<br />

language or in bona fide and established practices of trade;<br />

The examiner made the following criticisms of the mark:<br />

1. The mark is not capable of graphic representation, it is too indefinite, and is<br />

therefore ineligible for registration under Article 7 (1) (a).<br />

2. The mark is devoid of distinctive character because in relation to pharmaceutical<br />

preparations strawberry as a flavour is too commonly used as a mask for<br />

unpleasant products. In relation to sanitary products not used for buccal hygiene<br />

the mark will be wholly overlooked because there is no reason for consumers to<br />

taste the products. The mark is therefore ineligible for registration under Article 7<br />

(1) (b).<br />

3. The mark appeared to be descriptive of characteristics of pharmaceutical<br />

preparations, which is specifically barred under Article 7 (1) (c).

By the time of the appeal the examiner had waived his objection under article 7 (1) (a)<br />

but remained firm on the grounds set out under Article 7 (1) (b) & (c).<br />

The Board of Appeal reviewing the appeal held:<br />

• The objection under Article 7 (1) (b) was well founded.<br />

• The purpose of Article 7 (1) (b) to (e) is to prevent signs which any trader may<br />

legitimately wish to use from being reserved to the exclusive use of a single<br />

undertaking by means of registration as a trade mark.<br />

• The Board followed the rulings of the ECJ which have made clear the public<br />

interest does not want undue restriction of goods or services.<br />

See case C-104/01 Libertel v Benelux-Merkenbureau (CTM for the colour<br />

Orange).<br />

• The Board considered it the right of those making pharmaceutical products to be<br />

able to add flavouring to their products to disguise unpleasant taste. If the<br />

appellant were to be given exclusive right to use such a sign under Article 9 that<br />

would interfere unduly with the freedom of the appellant’s competitors.<br />

Note:<br />

Whilst the Board did not technically rule on the ability of the appellant’s application to<br />

satisfy the requirement that a sign be capable of graphical description they did comment:<br />

The use of a ‘gustatory sign’ required more than a mere description in words.<br />

LN1:#20078011v2

Shield Mark BV v Joost Kist h.o.d.n. Memex case C-283/01<br />

Article 2 of Directive 89/104 permits sounds to be registered as Trade Marks.<br />

Article 2 - Signs of which a trade mark may consist<br />

A trade mark may consist of any sign capable of being represented graphically,<br />

particularly words, including personal names, designs, letters, numerals, the shape<br />

of goods or of their packaging, provided that such signs are capable of<br />

distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other<br />

undertakings.<br />

The relevant national jurisdictions have however, not all permitted sound marks in the<br />

past.<br />

This action originated in the Kingdom of Belgium, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and<br />

the Kingdom of the Netherlands, who collectively legislate on Trade Marks.<br />

Their legislation on Trade Marks is known as LBM, and its administration was entrusted<br />

to an organisation termed BBM.<br />

When LBM was amended to take account of European Directives in 1995, Articles 2 & 3<br />

were not directly transposed in to the LBM.<br />

Since a decision of the Gerechtshof te’s Gravenhage (Regional Court of Appeal)<br />

(Netherlands) of May 27 th 1999, the BBM has refused to register sound marks.<br />

The simplified facts of this case:<br />

Shield Mark holds fourteen marks, registered with BBM. Four of those marks consist of<br />

a musical stave, two of which state; SOUND MARK. Four marks consist of the first 9<br />

notes of Für Elise.<br />

Shield Mark launched a radio campaign in 1992 using the first 9 notes of Für Elise in<br />

every advert. In 1993 Shield Mark also issued news sheets describing their services, and<br />

where they were displayed the same signature tune was heard each time a news sheet was<br />

removed from the stand. Shield Mark also publishes software and every time a disk is<br />

used a cockcrow is heard.<br />

Mr. Kist is a communications consultant, in particular in advertising law and trade mark<br />

law, he organises Intellectual Property seminars. During an advertising campaign in<br />

1995 he used the first 9 notes of Für Elise and sold a computer program which emitted a<br />

cockcrow when it started up.<br />

The Netherlands Appeal Court (Hoge Raad der Nederlanden) referred two questions to<br />

the ECJ:<br />

LN1:#20078011v2

1. (a) Must Article 2 of the Directive be interpreted as precluding sounds or noises<br />

from being regarded as trade marks?<br />

(b) If the answer to question 1(a) is in the negative, does the system established by<br />

the Directive require that sounds or noises must be capable of being regarded as<br />

trade marks?<br />

2. (a) If the answer to question 1(a) is in the negative, what requirements does the<br />

Directive lay down for sound marks as regards the reference in Article 2 to the<br />

need for the sign to be capable of being represented graphically and, in<br />

conjunction therewith, as regards the way in which the registration of such a trade<br />

mark must take place?<br />

LN1:#20078011v2<br />

(b) In particular, are the requirements referred to in (a) satisfied if the sound or the<br />

noise is registered in one of the following forms:<br />

- musical notes;<br />

- a written description in the form of an onomatopoeia;<br />

- a written description in some other form;<br />

- a graphical representation such as a sonogram;<br />

- a sound recording annexed to the registration form;<br />

- a digital recording accessible via the internet;<br />

- a combination of those methods;<br />

- some other form and, if so, which?<br />

The ECJ held:<br />

1. The wording of Article 2 does not exclude ‘Sound Marks’ and the list of<br />

permissible marks is not exhaustive.<br />

2. The Court agreed with the intervening Governments and Shield Mark that sounds<br />

were capable of registration.<br />

3. Consequently Article 2 is to be interpreted as permitting the registration of sound<br />

marks.<br />

4. Consequently Member States cannot preclude the registration of sound marks.<br />

5. The Court declined to rule on how a mark in the form of a sonogram, a sound<br />

recording, a digital recording or a combination of those methods should be<br />

graphically represented. Regarding acceptable forms of graphical representation<br />

the ECJ felt it was for the national court to determine, on a case by case basis.<br />

However, the ECJ added the following advice:<br />

a. The mark should state it is a ‘Sound Mark.’

LN1:#20078011v2<br />

b. The graphic representation must be precise; it is not enough to state the<br />

sound is ‘a cockcrow,’ and onomatopoeian language does not assist as the<br />

phonetics across the community vary too greatly.<br />

c. The ECJ recommends a stave be used to represent sound. A stave divided<br />

into bars, with clefs, and notes as appropriate.