Innovation and institutional change: the transition to a sustainable ...

Innovation and institutional change: the transition to a sustainable ... Innovation and institutional change: the transition to a sustainable ...

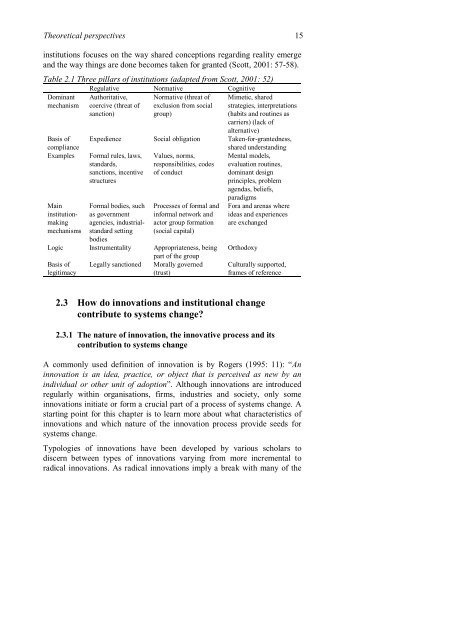

Theoretical perspectives 15 institutions focuses on the way shared conceptions regarding reality emerge and the way things are done becomes taken for granted (Scott, 2001: 57-58). Table 2.1 Three pillars of institutions (adapted from Scott, 2001: 52) Regulative Normative Cognitive Dominant Authoritative, Normative (threat of Mimetic, shared mechanism coercive (threat of exclusion from social strategies, interpretations sanction) group) (habits and routines as carriers) (lack of alternative) Basis of Expedience Social obligation Taken-for-grantedness, compliance shared understanding Examples Formal rules, laws, Values, norms, Mental models, standards, responsibilities, codes evaluation routines, sanctions, incentive of conduct dominant design structures principles, problem agendas, beliefs, paradigms Main Formal bodies, such Processes of formal and Fora and arenas where institution- as government informal network and ideas and experiences making agencies, industrial- actor group formation are exchanged mechanisms standard setting bodies (social capital) Logic Instrumentality Appropriateness, being part of the group Orthodoxy Basis of Legally sanctioned Morally governed Culturally supported, legitimacy (trust) frames of reference 2.3 How do innovations and institutional change contribute to systems change? 2.3.1 The nature of innovation, the innovative process and its contribution to systems change A commonly used definition of innovation is by Rogers (1995: 11): “An innovation is an idea, practice, or object that is perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption”. Although innovations are introduced regularly within organisations, firms, industries and society, only some innovations initiate or form a crucial part of a process of systems change. A starting point for this chapter is to learn more about what characteristics of innovations and which nature of the innovation process provide seeds for systems change. Typologies of innovations have been developed by various scholars to discern between types of innovations varying from more incremental to radical innovations. As radical innovations imply a break with many of the

16 Chapter 2 ways things were done in the past, they are often associated with systems change. In the innovation typology by Abernathy and Clark (1985: 5) the most radical innovations are those that make existing technologies obsolete and disrupt existing market linkages, and they labelled these architectural innovations, see the inner typology in the quadrants in Figure 2.1. This is contrasted with regular or incremental innovations that build upon existing competencies and linkages. If the nature of innovations is connected with the nature of systems change, a typology such as in the outer part of the quadrants in Figure 2.1 can be drawn. Although useful, this two-dimensional typology is too limited and does not take into account other relevant types of changes involved in systems change, such as in networks, institutions and the way the system is embedded in society. Figure 2.1 Typology of innovation and systems change (adapted from Abernathy and Clark, 1985: 8) Builds upon existing competences / extends existing technologies System transformation New markets Regular innovation Builds upon existing market linkages / expands existing customer markets Disrupts existing market linkages / creates new customer markets Revolutionary innovation Niche creation Architectural innovation System innovation New sociotechnical systems Disrupts existing competences / makes existing technologies obsolete Based on the model in Figure 2.1 the development and diffusion of radical innovations fundamentally changes or replaces existing systems. To induce radical innovations the previous dominance of theories based on a linear model of innovation led to a strong focus on science-driven and supply-push policies, as discoveries in basic science would precede inventions in applied science, and end with innovation and its diffusion (Freeman, 1996: 27). This dominance was also explained by the fact that at that time science had played an important role in the development of nuclear power while various innovations took place that were expected to lead to the use of nuclear power

- Page 2 and 3: INNOVATION AND INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

- Page 4 and 5: In de reeks Schone Technologie en M

- Page 6 and 7: Contents Preface v Chapter 1 Transi

- Page 8: Contents iii 6.4 Liberalisation of

- Page 11 and 12: vi Chapter This dissertation was fa

- Page 13 and 14: 2 Chapter 1 systems of production a

- Page 15 and 16: 4 Chapter 1 1995: 25). A basic tene

- Page 17 and 18: 6 Chapter 1 and be a member of natu

- Page 19 and 20: 8 Chapter 1 specific momentum for p

- Page 21 and 22: 10 Chapter 1 Chapter eight summaris

- Page 23 and 24: 12 Chapter 2 derive some general pr

- Page 25: 14 Chapter 2 emerges because of cha

- Page 29 and 30: 18 Chapter 2 multinational producer

- Page 31 and 32: 20 Chapter 2 increasing scale and r

- Page 33 and 34: 22 Chapter 2 of alternative views o

- Page 35 and 36: 24 Chapter 2 exchange of knowledge

- Page 37 and 38: 26 Chapter 2 multidirectional flux

- Page 39 and 40: 28 Chapter 2 systems are located at

- Page 41 and 42: 30 Chapter 2 - Misadaptation betwee

- Page 43 and 44: 32 Chapter 2 of these concepts and

- Page 45 and 46: 34 Chapter 2 New institutionalism i

- Page 47 and 48: 36 Chapter 2 production and consump

- Page 49 and 50: 38 Chapter 2 Figure 2.3 Model of an

- Page 51 and 52: 40 Chapter 2 traditional forms of d

- Page 53 and 54: 42 Chapter 2 2.4 Integrating insigh

- Page 55 and 56: 44 Chapter 2 2.4.1 Innovation as a

- Page 57 and 58: 46 Chapter 2 composition of the net

- Page 59 and 60: 48 Chapter 2 its diffusion, to crea

- Page 61 and 62: 50 Chapter 2 materials, and the pro

- Page 63 and 64: 52 Chapter 2 - specificity: as an e

- Page 65 and 66: 54 Chapter 2 often represents the p

- Page 67 and 68: 56 Chapter 2 that the introduction

- Page 69 and 70: 58 Chapter 2 2.5 Concluding remark

- Page 71 and 72: 60 Chapter 3 society. A further sec

- Page 73 and 74: 62 Chapter 3 perceptions and soluti

- Page 75 and 76: 64 Chapter 3 Linkages involve conne

Theoretical perspectives 15<br />

institutions focuses on <strong>the</strong> way shared conceptions regarding reality emerge<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> way things are done becomes taken for granted (Scott, 2001: 57-58).<br />

Table 2.1 Three pillars of institutions (adapted from Scott, 2001: 52)<br />

Regulative Normative Cognitive<br />

Dominant Authoritative, Normative (threat of Mimetic, shared<br />

mechanism coercive (threat of exclusion from social strategies, interpretations<br />

sanction)<br />

group)<br />

(habits <strong>and</strong> routines as<br />

carriers) (lack of<br />

alternative)<br />

Basis of Expedience Social obligation Taken-for-grantedness,<br />

compliance<br />

shared underst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

Examples Formal rules, laws, Values, norms, Mental models,<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ards,<br />

responsibilities, codes evaluation routines,<br />

sanctions, incentive of conduct<br />

dominant design<br />

structures<br />

principles, problem<br />

agendas, beliefs,<br />

paradigms<br />

Main Formal bodies, such Processes of formal <strong>and</strong> Fora <strong>and</strong> arenas where<br />

institution- as government informal network <strong>and</strong> ideas <strong>and</strong> experiences<br />

making agencies, industrial- ac<strong>to</strong>r group formation are ex<strong>change</strong>d<br />

mechanisms st<strong>and</strong>ard setting<br />

bodies<br />

(social capital)<br />

Logic Instrumentality Appropriateness, being<br />

part of <strong>the</strong> group<br />

Orthodoxy<br />

Basis of Legally sanctioned Morally governed Culturally supported,<br />

legitimacy<br />

(trust)<br />

frames of reference<br />

2.3 How do innovations <strong>and</strong> <strong>institutional</strong> <strong>change</strong><br />

contribute <strong>to</strong> systems <strong>change</strong>?<br />

2.3.1 The nature of innovation, <strong>the</strong> innovative process <strong>and</strong> its<br />

contribution <strong>to</strong> systems <strong>change</strong><br />

A commonly used definition of innovation is by Rogers (1995: 11): “An<br />

innovation is an idea, practice, or object that is perceived as new by an<br />

individual or o<strong>the</strong>r unit of adoption”. Although innovations are introduced<br />

regularly within organisations, firms, industries <strong>and</strong> society, only some<br />

innovations initiate or form a crucial part of a process of systems <strong>change</strong>. A<br />

starting point for this chapter is <strong>to</strong> learn more about what characteristics of<br />

innovations <strong>and</strong> which nature of <strong>the</strong> innovation process provide seeds for<br />

systems <strong>change</strong>.<br />

Typologies of innovations have been developed by various scholars <strong>to</strong><br />

discern between types of innovations varying from more incremental <strong>to</strong><br />

radical innovations. As radical innovations imply a break with many of <strong>the</strong>