FILM FILM - University of Macau Library

FILM FILM - University of Macau Library FILM FILM - University of Macau Library

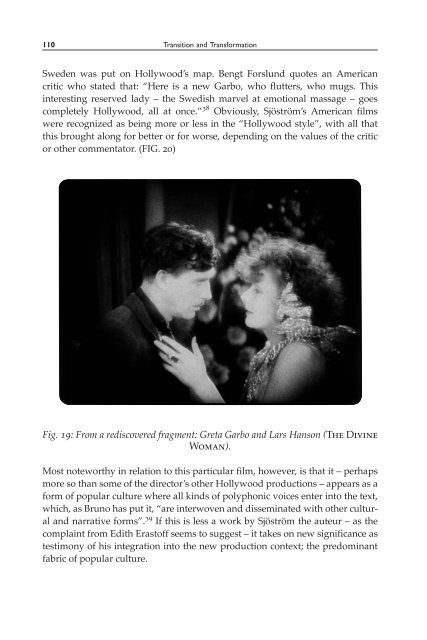

Fragmented Pieces: Writing the History of the Lost Hollywood Films 109 in his heart running down to the pier to catch up with his daughter. He is too late, and falls into the water. The last image shows his stick and hat floating on the dark surface... This is the only consequent ending. 34 The same debate on happy endings would later reoccur, as we have seen, in connection with The Wind. This question of happy endings indeed seems to have become a commonplace in critical discourses on American cinema in the 1920s; a metonymy for the supposed superficiality of Hollywood film culture. The Divine Woman – From Bernhardt to Garbo The story in The Divine Woman was originally supposed to portray The Divine Sarah, as the film was scripted by Dorothy Farnum, after a play by Gladys Unger: Starlight, about the life of Sarah Bernhardt. However, in the end little seems to have remained of the original Sarah, as the role had been completely adjusted to suit the American image of Garbo the actress: she who would become The Divine Garbo. Thus, this is the picture of the simple country girl who arrives in the big city and meets all of its temptations, making her the biggest of stars. But this means nothing compared to true love... Marianne (Greta Garbo), a young woman from Brittany neglected by her impoverished parents, longs to be an actress and moves to Paris. Here, she meets theatrical producer Henry Legrande (Lowell Sherman), who had once had an affair with Marianne’s mother and now takes care of her daughter. Marianne falls in love with a young deserter, Lucien (Lars Hanson). He steals a dress for her and ends up in jail. Now, Henry starts to court her, and Marianne is thus torn between her love and her loyalty towards the paternal figure. According to the original script, she was supposed to flee to South America with her beloved, but in the film, according to the cutting continuity script, she makes a suicide attempt that fails, whereupon the two lovers are happily reunited. 35 (FIG. 19) Bengt Forslund has noted that it was the fifth script version of The Divine Woman that received preliminary approval from Irving Thalberg, after which, however, the approval was withdrawn and three more script versions had to be submitted before final approval. Forslund also quotes Sjöström’s wife, who is supposed to have said that he shouldn’t make “those kinds of films”. 36 The Swedish critic in the leading film magazine Filmjournalen, though, was rather positive, attributing the film to “our own” Victor Sjöström. 37 These possessive traits appear only late in the director’s American career; it is as if the need to remind the audience of his Swedishness became more urgent as time passed, but there is also a vein of Swedish national pride in the comments: through Sjöström, as well as through Garbo, who was also mentioned in the reviews,

110 Transition and Transformation Sweden was put on Hollywood’s map. Bengt Forslund quotes an American critic who stated that: “Here is a new Garbo, who flutters, who mugs. This interesting reserved lady – the Swedish marvel at emotional massage – goes completely Hollywood, all at once.” 38 Obviously, Sjöström’s American films were recognized as being more or less in the “Hollywood style”, with all that this brought along for better or for worse, depending on the values of the critic or other commentator. (FIG. 20) Fig. 19: From a rediscovered fragment: Greta Garbo and Lars Hanson (The Divine Woman). Most noteworthy in relation to this particular film, however, is that it – perhaps more so than some of the director’s other Hollywood productions – appears as a form of popular culture where all kinds of polyphonic voices enter into the text, which, as Bruno has put it, “are interwoven and disseminated with other cultural and narrative forms”. 39 If this is less a work by Sjöström the auteur – as the complaint from Edith Erastoff seems to suggest – it takes on new significance as testimony of his integration into the new production context; the predominant fabric of popular culture.

- Page 60 and 61: From Scientist to Clown - He Who Ge

- Page 62 and 63: From Scientist to Clown - He Who Ge

- Page 64 and 65: A for Adultery - The Scarlet Letter

- Page 66 and 67: A for Adultery - The Scarlet Letter

- Page 68 and 69: A for Adultery - The Scarlet Letter

- Page 70 and 71: and being-seen” -takes the relati

- Page 72 and 73: A for Adultery - The Scarlet Letter

- Page 74 and 75: A for Adultery - The Scarlet Letter

- Page 76 and 77: A for Adultery - The Scarlet Letter

- Page 78: A for Adultery - The Scarlet Letter

- Page 81 and 82: 80 Transition and Transformation Mo

- Page 83 and 84: 82 Transition and Transformation it

- Page 85 and 86: 84 Transition and Transformation sh

- Page 87 and 88: 86 Transition and Transformation Th

- Page 89 and 90: 88 Transition and Transformation wh

- Page 91 and 92: 90 Transition and Transformation Fr

- Page 93 and 94: 92 Transition and Transformation po

- Page 95 and 96: 94 Transition and Transformation op

- Page 97 and 98: 96 Transition and Transformation he

- Page 99 and 100: 98 Transition and Transformation Th

- Page 101 and 102: 100 Transition and Transformation p

- Page 103 and 104: 102 Transition and Transformation t

- Page 105 and 106: 104 Transition and Transformation F

- Page 107 and 108: 106 Transition and Transformation F

- Page 109: 108 Transition and Transformation d

- Page 113 and 114: 112 Transition and Transformation W

- Page 115 and 116: 114 Transition and Transformation F

- Page 117 and 118: 116 Transition and Transformation e

- Page 119 and 120: 118 Transition and Transformation o

- Page 121 and 122: 120 Transition and Transformation h

- Page 123 and 124: 122 Transition and Transformation p

- Page 125 and 126: 124 Transition and Transformation T

- Page 127 and 128: 126 Transition and Transformation I

- Page 129 and 130: 128 Transition and Transformation c

- Page 131 and 132: 130 Transition and Transformation e

- Page 133 and 134: 132 Transition and Transformation a

- Page 135 and 136: 134 Transition and Transformation b

- Page 137 and 138: 136 Transition and Transformation t

- Page 139 and 140: 138 Transition and Transformation 1

- Page 141 and 142: 140 Transition and Transformation 1

- Page 143 and 144: 142 Transition and Transformation 2

- Page 145 and 146: 144 Transition and Transformation 2

- Page 147 and 148: 146 Transition and Transformation 1

- Page 149 and 150: 148 Transition and Transformation 2

- Page 151 and 152: 150 Transition and Transformation

- Page 153 and 154: 152 Transition and Transformation

- Page 155 and 156: 154 Transition and Transformation K

- Page 157 and 158: 156 Transition and Transformation H

110 Transition and Transformation<br />

Sweden was put on Hollywood’s map. Bengt Forslund quotes an American<br />

critic who stated that: “Here is a new Garbo, who flutters, who mugs. This<br />

interesting reserved lady – the Swedish marvel at emotional massage – goes<br />

completely Hollywood, all at once.” 38 Obviously, Sjöström’s American films<br />

were recognized as being more or less in the “Hollywood style”, with all that<br />

this brought along for better or for worse, depending on the values <strong>of</strong> the critic<br />

or other commentator. (FIG. 20)<br />

Fig. 19: From a rediscovered fragment: Greta Garbo and Lars Hanson (The Divine<br />

Woman).<br />

Most noteworthy in relation to this particular film, however, is that it – perhaps<br />

more so than some <strong>of</strong> the director’s other Hollywood productions – appears as a<br />

form <strong>of</strong> popular culture where all kinds <strong>of</strong> polyphonic voices enter into the text,<br />

which, as Bruno has put it, “are interwoven and disseminated with other cultural<br />

and narrative forms”. 39 If this is less a work by Sjöström the auteur – as the<br />

complaint from Edith Erast<strong>of</strong>f seems to suggest – it takes on new significance as<br />

testimony <strong>of</strong> his integration into the new production context; the predominant<br />

fabric <strong>of</strong> popular culture.