“Green Ring” production - Seattle Opera

“Green Ring” production - Seattle Opera

“Green Ring” production - Seattle Opera

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong><br />

<strong>“Green</strong>” Ring Press Kit<br />

“In <strong>Seattle</strong>, Glynn Ross audaciously resolved to mount Wagner’s<br />

Ring of the Nibelung every summer in both German and English,<br />

starting in 1975. Speight Jenkins, who took over the <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong><br />

in 1983, is an equally zealous Wagnerite (the office closes for<br />

Wagner’s birthday) who insisted on world- class music and<br />

<strong>production</strong> values. This meant relinquishing Ross’s annual Ring in<br />

favor of more-varied summer repertoire keying on fresh<br />

<strong>production</strong>s of Lohengrin, the Ring, Tristan, Die Meistersinger,<br />

and Parsifal. <strong>Seattle</strong>’s 1986 Ring, directed by Francois Rochaix<br />

and designed by Robert Israel, remains the only North American<br />

version with the intellectual panache of Patrice Chereau’s<br />

landmark Bayreuth Ring of 1976. <strong>Seattle</strong>’s 2001 Ring, directed by<br />

Stephen Wadsworth, was hyperrealistic yet psychologically astute.<br />

Both <strong>production</strong>s were cast not according to glamorous past<br />

exposure but actual competence shrewdly assessed; both were<br />

complemented by first-rate Wagner lectures and (an amenity<br />

unknown at Lincoln Center or Carnegie Hall) a serious bookstore.<br />

The one Ring secured and the other consolidated <strong>Seattle</strong>’s status as<br />

the leading North American Wagner house.”<br />

Joseph Horowitz<br />

Classical Music in America

<strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> Public Programs and Media Department<br />

Jonathan Dean<br />

Director of Public Programs and Media<br />

206.676.5543<br />

jonathan.dean@seattleopera.org<br />

Tamara Vallejos<br />

Public Programs and Media Associate<br />

206.676.5559<br />

tamara.vallejos@seattleopera.org<br />

For visuals (digital photographs or video):<br />

Monte Jacobson<br />

Public Relations Coordinator<br />

206.676.5545<br />

monte.jacobson@seattleopera.org<br />

Press releases and other information also available at:<br />

http://www.seattleopera.org/news/

Review Quotes: <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’s Ring III<br />

Production Review Quotes<br />

“Like a towering fir tree that survives after the primeval forest around it has vanished, the<br />

<strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’s <strong>production</strong> of Wagner’s Ring Cycle now stands alone as the only traditional<br />

depiction of the epic music drama on the American stage. And tall and proud it stands,<br />

indeed...magnificent to look at and imaginatively staged.”<br />

—Mike Silverman, The Associated Press, 8/17/2009<br />

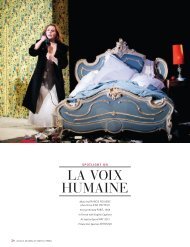

“The Technicolor © brilliance and sylvan detail of the <strong>production</strong> (the collaborative brainchild of<br />

director Stephen Wadsworth, scenic designer Thomas Lynch, costume designer Martin<br />

Pakledinaz and lighting designer Peter Kaczorowski) are astounding.”<br />

—James C. Whitson, <strong>Opera</strong> News, November 2009<br />

“The <strong>production</strong> remains realistic without being kitschy and succeeded to presenting Wagner’s<br />

Ring rather than some director’s concept of it. All the characters become complex and often<br />

sympathetic human beings here, not robots or cartoon figures.”<br />

—John Louis diGaetani, Wagnerianni, Spring 2010<br />

“The <strong>Seattle</strong> Symphony Orchestra is one of the most experienced in the world when it comes to<br />

Wagner, and serves up Wagner’s entire range of orchestral magic with convincing power.”<br />

—David Schiff, Opernwelt, November 2001<br />

“For all its beauty and naturalism, the real triumph of this Ring was its singing.”<br />

—David Stabler, The Oregonian, “Searing `Gotterdammerung’ ends cycle” 8/13/2001<br />

“<strong>Seattle</strong> has many claims to fame, for Boeing, the American aircraft giant, for Bill Gates’<br />

Microsoft, and perhaps, most universally, for Frasier. For Wagnerites, however, <strong>Seattle</strong> means<br />

the Ring. The <strong>Seattle</strong> Ring is infinitely worth the round trip of 13,000 miles, and wild horses will<br />

not keep me away when it is staged again in five years time.<br />

—Paul Dawson-Bowling, UK Wagner Society newsletter, “Wunder Muss Ich Euch Melden: The<br />

<strong>Seattle</strong> Ring,” December 2001

Singer Review Quotes<br />

“[Greer] Grimsley was every bit the master god. Hiss bass-baritone not only is big and untiring,<br />

it is voluminous, with ever-changing color, now intense and cutting, now dark, now ringing and<br />

stentorian. And he’s mobile and quick, his whole body the portrait of the mood and emotion.<br />

The shift he made from the towering rage at his willfully disobedient daughter, to the grief and<br />

loss shown at his final farewell from Brünnhilde, was tremendous, and the separation more<br />

loving and moving than I have ever experienced of other Wotans.”<br />

—Robert Commanday, San Francisco Classical Voice, 8/11/2009<br />

“Seldom does the role of Fricka dominate a “Walküre” so compellingly as when Stephanie<br />

Blythe is singing. Her voice just gets more amazing with each performance: huge, sumptuous,<br />

beautifully crafted waves of mezzo-soprano brilliance. Each note was a thrill. Never has one<br />

wished more fervently that Fricka had been given more to sing.<br />

—Melinda Bargreen, The <strong>Seattle</strong> Times, 8/11/2009<br />

“The venomous Alberich of Richard Paul Fink swaggered with lethal assurance, blustering<br />

about in a huge, gritty baritone.”<br />

—James C. Whitson, <strong>Opera</strong> News, November 2009<br />

“The star of Siegfried was without question the San Francisco-based tenor Dennis Peterson as<br />

Mime, a role usually tackled by aging and hammy character singers. Peterson actually sang all of<br />

his music well without losing any of the humor and even pathos of this fascinating, annoying,<br />

and complex role.”<br />

—Fred Haumptman, Crosscut, 8/15/2009<br />

“Stuart Skelton’s ringing, clear tenor, reminiscent of Set Svanholm’s, and his bold, confident<br />

carriage made his Siegmund an imposing, heroic figure.”<br />

—Robert Commanday, San Francisco Classical Voice, 8/11/2009<br />

“Margaret Jane Wray is gaining attention these days, consistently singing major roles at the<br />

Met. To judge from her Brangäne here, the spreading fame is well-deserved. Hers is a soprano<br />

approach to this Zwischenfach role, slightly steely at the top, but clearly projected and delivered,<br />

with plenty of volume.<br />

—Andrew Moravcsik, <strong>Opera</strong> Today, 8/15/2010

Full Articles and Reviews<br />

The <strong>“Green</strong>” Ring<br />

“The <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> Ring Cycle Design & Technical Team,” Entertainment Design, 2001<br />

“As Nature Intended: Designing a ‘Green’ Ring Cycle for the <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>,”<br />

Entertainment Design, 2001<br />

“Nature Rules in Triumphant Ring,” Wall Street Journal, 2001<br />

“<strong>Seattle</strong> Ring cycle a triumph,” San Francisco Chronicle, 2001<br />

“Der Postindustrielle Siegfried,” Opernwelt, 2001<br />

“Wagner’s ‘Ring’ in <strong>Seattle</strong> – Klingedes Museum,” Rondo, 2005<br />

“<strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’s once and future ‘Ring,’” The <strong>Seattle</strong> Times, 2009<br />

“If It’s Tuesday, It Must Be ‘Siegfried,’” The New York Times, 2009<br />

“The Ring at the Heart of <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>,” 2012/13 Souvenir Book

Opernwelt 11/2001:<br />

The postindustrial Siegfried<br />

The outstanding success of <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>'s new <strong>production</strong> of Wagner' s "Ring" could be<br />

simply observed by the fact, that the audience celebrated the singers in every intermission<br />

and discussed vividly the nature of Wagner's characters.<br />

Speight Jenkins, the General Director of <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> and Stephen Wadsworth, the director<br />

of the "Ring," are the ones responsible for these reactions.<br />

Jenkins put together a cast mainly consisting of Americans, Canadians and British that for the<br />

most part was beyond all expectations. Jane Eaglen as Brünnhilde, Margaret Jane Wray as<br />

Sieglinde, Stephanie Blythe as Fricka and Nancy Maultsby as Erda/Waltraute especially<br />

distinguished themselves. Eaglen, who too often is criticised for her acting, filled the role of<br />

Brünnhilde impressively with life, by planning Brünnhilde's emotional escalation carefully, to<br />

finally let it culminate in the immolation scene. Wray's voice conveyed a seemingly eerie<br />

quality. Her voice endowed Sieglinde's fragility and desperation with a sweet colouring that<br />

stood in perfect contrast to Eaglen's more blaring voice. Stephanie Blythe and Margaret Jane<br />

Wray finally returned as two of the Norns and took advantage of this re-entrance to show all off<br />

of their vocal mastery.<br />

The male cast was more heterogeneous, mainly because of Alan Woodrow's injury, which<br />

made him sing his first Siegfried backstage while Richard Berkeley-Steele acted the part on<br />

stage (in the following two weeks Berkeley-Steele also sang the part himself). This<br />

circumstance proved the more unfortunate, since Woodrow sang Siegfried as a heroic but still<br />

very human figure, while Berkeley-Steele fit the part visually better through his agility and<br />

obvious youth. Further outstanding male singers were the Danish bass Stephen Milling as<br />

Fasolt and Hunding, Richard Paul Fink as Alberich and Mark Baker as Siegmund. Milling was<br />

celebrated as the discovery of the whole cycle. He posseses an enormous range of voice,<br />

incredible vocal colours and an impressive stage presence. Fink was nearly on the same level<br />

and shaped Alberich threatening and sympathetic at the same time. Thomas Harper as Mime<br />

avoided stereotype funny elements of the role, without denying Mime's potential of evilness.<br />

Peter Kazaras was an impressive Loge, although the director Stephen Wadsworth seemed to be<br />

unable to decide what to do with this colourful figure. The only real disappointment was Philip<br />

Joll's Wotan who lacked (comparatively) vocal presence and determination.<br />

<strong>Seattle</strong>'s former "Ring" from 1985 was a postmodern, "postchéreau" approach by François<br />

Rochaix which contained high-tech special effects which achieved the amount of applause as<br />

the singers. This new <strong>production</strong>, also called "The Green Ring", sets the action into a wood,<br />

which didn't look like the Rhine-Area at all. Over all, this surtitled <strong>production</strong> could be<br />

characterised as rather "ungermanic".

This "Ring," with Thomas Lynch's realistic set and Martin Pakledinaz' eclectic costumes,<br />

avoids any political or mystic statement and emphasizes instead the individual psychological<br />

aspects of the figures (more in the actor's studio tradition than in the sense of Freud or Jung)<br />

and exposed several details, which sometimes helped the development of the plot, but also<br />

sometimes distracted from the focus of the story.<br />

One critic called this <strong>production</strong> a "Verismo-Ring" which suits it very well. Wadsworth’s<br />

approach had its strongest moment in the human moments of Wagner's drama and its weakest<br />

when the human elements get transcendent.<br />

The concept (mis)leaded to a new provocative view of the characters: Fricka and Alberich<br />

gained importance during "Rheingold", while Wotan degenerated to a reckless opportunist, an<br />

interpretation which affected the following operas badly, because we couldn't develop the<br />

necessary sympathy for Wotan's big plans. In spite of these difficulties, there were many great<br />

moments: They reached from Alberich's curse, which probably rocked the whole Pacific<br />

Northwest, to the extremely funny "sports- activities" of the Rhinemaidens when they welcome<br />

Siegfried in "Götterdämmerung". Unfortunately the very final scene was the weakest one of the<br />

whole <strong>production</strong>: The gods seemed to celebrate their end in some kind of New-Year’s-Party.<br />

On the other hand what should top Jane Eaglen's singing in the "Immolation-Scene"?<br />

The <strong>Seattle</strong> Symphony Orchestra is one of the most experienced Wagner orchestras of the<br />

world and served the whole range of Wagner's orchestral magic in a very convincing way. The<br />

American Franz Vote conducted very fluently and balanced although there was a lack of<br />

distinguishing individual note. The first two operas seemed to be musically not very structured<br />

and Wotan’s Farewell lacked sparkling energy. The sound of the last two operas seemed to be<br />

much more fluent,<br />

<strong>Seattle</strong> takes Wagner seriously: 800 people attended a five-hour-symposium after "Walküre",<br />

several hundred people came as well to Perry Lorenzo's pre- performance talks and to Speight<br />

Jenkins Question-and-Answer sessions after the shows at night. Jenkins managed to establish<br />

<strong>Seattle</strong> as "Alternative Bayreuth" (difficult to translate: In German the term is "Gegen-<br />

Bayreuth" which could mean "Anti-Bayreuth" or "Counter-Bayreuth", but I'm sure from the<br />

context he wants to express that Wagner fans really have the choice to go to <strong>Seattle</strong> or to<br />

Bayreuth, because they are on the same level) using the work of his predecessor Glynn Ross,<br />

but without any false "Familycult" or historical mysticism. The hometown of Boeing and<br />

Microsoft (the industrial Wotan and the post-industrial Siegfried?) seems to be the perfect place<br />

to carry Wagner into the 21 st Century. <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> plans to revive this Ring <strong>production</strong> in<br />

2005 in the newly renovated <strong>Opera</strong> House which is supposed to open with a new "Parsifal" in<br />

2003<br />

David Schiff

ENGLISH:<br />

WAGNER’S "RING" IN SEATTLE<br />

Sounding Museum<br />

Breiholz Backstage – May 2005<br />

In American <strong>Seattle</strong> they play Wagner by the book. After the completely postmodern<br />

“<strong>Ring”</strong> adaptations of the last few years, it’s almost refreshing. At least according to<br />

Jochen Breiholz, who saw the most recent performances.<br />

For Wagnerians, <strong>Seattle</strong> has above all else a golden sound: <strong>Seattle</strong>, the American Bayreuth.<br />

The call went out in the middle of the 70's, when Glynn Ross, who founded <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> in<br />

1963, presented "Der Ring des Nibelungen" at his house for the first time. Until 1983, the<br />

company played the tetralogy each season, always alternating between German and<br />

English. No other American opera house has such continuity.<br />

The three cycles presented at <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> this August have been sold out since last<br />

autumn. The "Ring" in <strong>Seattle</strong> is a cult and without a doubt the city’s most important<br />

cultural event. A must for anyone who wants to belong. One goes to the events and<br />

performances relaxed. Nothing to do with sacred consecration—Bayreuth is far; no fiercely<br />

earnest, transfigured gazes. Many in the audience look as though they were going to a<br />

beach party. Flip-flops and shorts are not strange. Of course there’s also the occasional<br />

smoking jacket, the lonely evening dress, but whatever pleases is allowed. And what<br />

pleases most people is that no dress code exists to which they must conform.<br />

Then we get started exactly where good old Richie put it in the stage directions: at the<br />

bottom of the Rhine. The Rhine maidens swim in dizzying heights. That is, they hang above<br />

the stage and are pulled through the air, up and down and sideways. Their mermaidfishtails<br />

glitter like silver. Director Stephen Wadsworth and his set designer Thomas Lynch<br />

follow the words of the master at every turn. Almost always. Mountains heights, wild<br />

forests, rocky clefts. If it was the will of the collected-art-worker Wagner that the gods<br />

climb up a rainbow to enter Valhalla at the end of Das Rheingold – thank you very much,<br />

that’s what they do in <strong>Seattle</strong>! Granted, it’s technically so brilliant that we are astonished<br />

and deeply impressed. Where else in the world can you see this? Even Otto Schenk’s<br />

<strong>production</strong> at New York's Met doesn’t stick so closely to the images that Wagner wanted.<br />

Of course, we could now turn away, horrified, and cry out "Kitsch!" Of course, we could say<br />

that this is from yesteryear, no longer a measure of the times, and above all laughable. But<br />

we don’t do that. <strong>Seattle</strong> gives us the opportunity to the "Ring" as it was originally intended.<br />

It’s like a journey through time, like a museum, to be sure, but museums aren’t bad because<br />

they display something from another time. Everyone is familiar with "Ring"-stagings set in<br />

the 19th century or in the 20's or in the present or in the future, starring managers,<br />

bankers and gangsters. Barely anyone, even the most widely travelled Wagnerians knows<br />

something else. Here, the dragon looks like it comes from Steven Spielberg's "Jurassic<br />

Park". It even has wings. Dragons must look like that!

The cast? Ewa Podles is a grandiose Erda, Stephanie Blythe a brilliant Fricka. Unacceptable,<br />

however, the Brunnhilde of Jane Eaglen, whose voice has long since passed its best days.<br />

But the orchestra, under Robert Spano, can contend with more famous orchestras: Wagner<br />

weaves and floats and flows and flickers here, carrying us away in rapture.

The year was 1975, and the early-evening summer sun was still shining<br />

when the lengthy standing ovations inside the <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> House finally<br />

subsided. The shell-shocked capacity audience for <strong>Seattle</strong>’s first complete<br />

Der Ring des Nibelungen had just seen and heard the world end. And as<br />

they staggered outside, clutching their programs and their “I was a Willing<br />

Participant in the <strong>Seattle</strong> Wagner Orgy” T-shirts and their replica horned<br />

helmets from the gift shop, they knew they were changed forever.<br />

What nobody quite realized at that point was that <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> was<br />

changed forever, too. Mastering the Ring over 37 years in three very<br />

different <strong>production</strong>s and with hundreds of international cast members,<br />

conductors, and stage directors gave the company a level of expertise<br />

impossible to attain in less ambitious circumstances. Now, as we approach<br />

an exciting 2012/13 season, <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> and its audiences will reap the<br />

benefits—in stagecraft, technology, education, directing, orchestral performance,<br />

even box office efficiency—that have been honed by the company’s<br />

long history with Wagner. And two of this season’s most eagerly awaited<br />

<strong>production</strong>s, Puccini’s Turandot and Beethoven’s mighty Fidelio, will be led<br />

by Asher Fisch, <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’s principal guest conductor and conductor of<br />

the next Ring (in August of 2013).<br />

Back in 1975, <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’s founding general director Glynn Ross<br />

planned to present the Wagnerian epic as a separate entity each summer<br />

in a forested location between <strong>Seattle</strong> and Tacoma, but those “Festival in<br />

the Forest” plans never materialized. Instead, the Ring became internalized<br />

in <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>, rather than a separate festival, and has become the heart<br />

of the company—providing the pulse of everything <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> does,<br />

from the non-Ring operas to the educational programs.<br />

What changes hath the Ring wrought? Wagner’s tetralogy brought to<br />

<strong>Seattle</strong> the ultimate Ring enthusiast, Speight Jenkins—first as a Ring lecturer,<br />

then as Ross’s successor in the general director’s chair. The attention of the<br />

world is focused on <strong>Seattle</strong> during the Ring, which has put <strong>Seattle</strong> on the<br />

international cultural map as no other artistic endeavor probably could<br />

have done. The Ring has transformed the company’s technology team into<br />

a team with no limits, one that literally can handle any challenge in the<br />

world of stagecraft. <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’s educational programming has been—and<br />

continues to be—deeply influenced by Wagner and his works. The <strong>Seattle</strong><br />

Above: <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> Founding Director Glynn Ross (center) with Valkyrie Jeanne Cook and Fafner the giant Noel Mangin in <strong>Seattle</strong>, 1978<br />

Opposite: Siegfried (Stig Anderson) confronts Fafner the dragon in <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’s 2009 Siegfried<br />

66 2012/13 SeaSon at <strong>Seattle</strong> opera<br />

the Ring<br />

at the Heart of<br />

<strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong><br />

By Melinda Bargreen<br />

Dale wittner photo

Chris Bennion photo

Chris Bennion photo<br />

Symphony Orchestra, which as the orchestra of<br />

<strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> has played all the Rings since the<br />

pre-1975 presentations of the individual operas<br />

inside the company’s regular seasons, has not<br />

only made recordings as “America’s Wagner<br />

Orchestra,” but has also grown and developed to<br />

handle the heroic requirements Wagner made of<br />

his instrumentalists.<br />

“The Ring is the reason I wanted to come here<br />

(to <strong>Seattle</strong>),” Jenkins explains. “It’s very rare for<br />

an opera company to have a niche like this, but<br />

because of Glynn Ross’s brilliant marketing,<br />

when people said ‘<strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’ it meant ‘the<br />

Ring.’ The Ring has been our heart; it’s what<br />

makes us. And it has made <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> ready<br />

to meet any challenge: there’s no opera we can’t<br />

do if we do the Ring.”<br />

Through its work on the Ring the company has<br />

learned how to deal with 25 major artists at<br />

68 2012/13 SeaSon at <strong>Seattle</strong> opera<br />

once “from a personal, professional, and even<br />

medical basis,” as Jenkins puts it.<br />

One big reason the Ring has seeped into every<br />

<strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> <strong>production</strong> is that Stephen<br />

Wadsworth, who has staged the current Ring,<br />

has set a new standard for staging in everything<br />

the company does. His direction has created a<br />

taut psychological drama that probes the characters’<br />

motivation and interactions in a way that<br />

has become the company’s “new normal”; after<br />

you’ve had this kind of theater on the opera<br />

stage, you’re not willing to settle for anything<br />

less. Stage director Tomer Zvulun, who has<br />

worked with Wadsworth as assistant director on<br />

the Ring (as well as in the company’s Iphigénie<br />

en Tauride and Der Fliegende Holländer), says<br />

that this association has been “the most<br />

important to my education. What I have learned<br />

goes to work with me every day of the year. I’m<br />

Left: Greer Grimsley (Wotan) and Janice Baird (Brünnhilde), 2009<br />

Below: Asher Fisch rehearses the <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> Orchestra<br />

Opposite top: Tim Buck, Fire Designer and Flight Technical Director, inspects the<br />

gorge set, along with the carpenter crew<br />

Opposite bottom: Gordon Hawkins (Gunther), Marie Plette (Gutrune) and<br />

Monte Jacobson (the Woman in White)<br />

Rozarii Lynch photo<br />

not interested in just putting people out there<br />

on the stage looking good with the lights and<br />

costumes. <strong>Opera</strong> is not just a vocal vehicle; it can<br />

be presented in an almost cinematic way.”<br />

Zvulun, who recently staged the company’s<br />

much-lauded Lucia di Lammermoor with<br />

Aleksandra Kurzak and will direct La bohème in<br />

<strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’s 2012/13 season, says he will bring<br />

to this season’s <strong>production</strong> the lessons he has<br />

learned in close work with the Ring—different as<br />

Wagner may be from Puccini.<br />

“This is something Stephen [Wadsworth] is<br />

so good at: finding the humanity beneath the<br />

words and the score. From working on the Ring,<br />

I have learned so many truths about my own life,<br />

and my connection to my family.”<br />

Beneath the stage in the orchestra pit, the<br />

lessons of the Ring make a lasting and important

impression on the orchestral musicians. Bruce<br />

Bailey, a <strong>Seattle</strong> Symphony cellist who has played<br />

almost every <strong>Seattle</strong> Ring since the operas were<br />

first unveiled singly during the early 1970s, says<br />

the experience “can do nothing but improve your<br />

technique and give you stamina. This is really<br />

great music. After you hear it 15 or 20 times,<br />

you discover that you never realized before<br />

what you were actually hearing.” Bailey’s wife,<br />

Mariel, a member of the first violin section, adds:<br />

“There’s no question that the Ring has improved<br />

my playing massively. It requires things that are<br />

just jaw-droppingly hard. A few passages in the<br />

score are technically unplayable, but I absolutely<br />

try to play every note. And you learn to pace<br />

yourself! During my first Ring, I just fell back in<br />

my chair exhausted after Siegfried.”<br />

Symphony bassoonist Paul Rafanelli was just 13<br />

when he begged his mother to buy him tickets<br />

to the 1976 Ring. A member of the <strong>Opera</strong> Guild<br />

in his hometown of Bellingham arranged for<br />

him to observe Ring rehearsals, meeting several<br />

of the singers and the famous stage director<br />

George London.<br />

“I didn’t start playing the bassoon until later,<br />

but to be now playing the Ring with the same<br />

company where I first saw it performed is<br />

something I really cherish about my career<br />

Gary Smith photo<br />

here,” Rafanelli adds. He believes playing the<br />

Ring makes the orchestra more flexible and<br />

adaptable—and that hearing the singers informs<br />

his approach to his own instrument in terms of<br />

breathing, phrasing, and inflection.<br />

Nobody in the company has had as much Ring<br />

experience as Monte Jacobson, who has appeared<br />

in every <strong>Seattle</strong> Ring cycle (first as a singer in the<br />

chorus for Götterdämmerung, more lately as a<br />

supernumerary dubbed “the Woman in White,”<br />

and since 1983, also a full-time employee and<br />

archivist in <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’s offices). She vividly<br />

Rozarii Lynch photo<br />

2012/13 SeaSon at <strong>Seattle</strong> opera 69

Bill Mohn photo<br />

Left: Associate Director Gina<br />

Lapinski rehearses aerial moves<br />

with Rhine Daughters Jennifer Hines<br />

(Flosshilde) and Michele Loisier<br />

(Wellgunde)<br />

Top right: The fire in<br />

Götterdämmerung is about to<br />

consume Brünnhilde (Marilyn<br />

Zschau) in 1995<br />

Bottom right: Having learned to<br />

control large fires onstage, the<br />

company incorporated this skill in<br />

the 1997 Il trovatore, with Mark S.<br />

Doss (Ferrando)<br />

Opposite left: Michele Loisier also<br />

flew above the <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> stage<br />

when she played the goddess Diane<br />

in Iphigénie en Tauride in 2007<br />

Opposite right: Hojotoho! Students<br />

from the Evergreen school join<br />

Young Artists Megan Hart and<br />

Margaret Gawrysiak as Valkyries in<br />

Siegfried and the Ring of Fire, 2009<br />

70 2012/13 SeaSon at <strong>Seattle</strong> opera<br />

Greg Eastman photo Gary Smith photo<br />

recalls “standing on the stage, never having heard<br />

the Ring before, surrounded by this spectacular<br />

music and all the excitement of the Gibichungs<br />

called in with all their spears and weapons.”<br />

Over the years and the three different Ring<br />

<strong>production</strong>s, Jacobson has seen the company<br />

“grow into all these abilities that we now have.<br />

The attitude in the house now is, ‘We can do<br />

anything!’”<br />

Of all the participants involved in creating<br />

<strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’s Ring, the most visibly exciting<br />

work undoubtedly comes from the technical<br />

team headed by the dauntless Robert Schaub.<br />

His affection for Wagnerian opera is evident in<br />

every pronouncement: “The Ring is the Super<br />

Bowl event of the opera world. It’s the World<br />

Series! It is the pinnacle of our endeavor. And<br />

everything we do at <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> is informed<br />

by the Ring. After you’ve done that, all the other<br />

operatic challenges are manageable. If you climb<br />

Everest every few years, climbing Mount Rainier<br />

is not so bad.”<br />

Doing the Ring was a major factor influencing<br />

the design and amenities of Marion Oliver McCaw<br />

Hall, a rebuilt version of the former <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong><br />

House. The new hall opened in 2003. This led the<br />

way to vastly improved technical feats.<br />

“Because of the Ring, we can do flight,” Schaub<br />

explains, noting the famous flying Valkyrie horses<br />

of the previous Ring and the airborne Rhine<br />

Daughters of the current <strong>production</strong> (revived in<br />

the summer of 2013). “Because of the Ring, we can<br />

do pyrotechnics; we’ve done the R&D (research<br />

and development) and gotten people licensed,

Rozarii Lynch photo<br />

and everything is in-house—and the savings are<br />

huge. And now I get the fire [in Die Walküre and<br />

Götterdämmerung] just like I want it.”<br />

Meeting the technical demands of the Ring has<br />

made amazing things possible. Schaub’s team<br />

runs a digitizer pin over an object, such as a rock,<br />

and it draws the object on a computer, where it<br />

can be sectored and analyzed, and finally built to<br />

a much bigger scale. And sometimes you have to<br />

rotate that rocky unit, too, and it might weigh<br />

15,000 pounds. Because Wagner’s score demands<br />

huge scenery changes in very short time frames,<br />

the set elements must be able to move quickly.<br />

If you have only two minutes and 50 seconds of<br />

music to whisk away the Rhine Daughters’ world<br />

at the bottom of the Rhine and replace it with<br />

the gods’ domain, you have to know precisely<br />

Justina Schwartz photo<br />

where that underwater world is going and who<br />

is taking it there.<br />

“When you’re designing a dragon, you need trigonometry,<br />

geometry, physics,” Schaub explains.<br />

“How much weight needs to be on this lever, and<br />

what materials will work? Let’s try to break it!<br />

Will it snap and break if you drop it? What size of<br />

cables will we need? What kind of silk will work<br />

for the dragon’s skin?”<br />

The advance planning required by the Ring<br />

makes the company unusually proactive, a great<br />

advantage in a world where upcoming opera<br />

<strong>production</strong>s might be scheduled as long as five<br />

years in advance. To cite only one example: The<br />

airborne maneuvers of the Rhine Daughters are<br />

so physically laborious (never mind the singing!)<br />

that the singers take a year to work out with<br />

trainers and exercise equipment. (“They lose 20<br />

pounds, they look great, and they always say<br />

‘Thank you!’” Schaub notes.) “Our staff is stronger<br />

and tougher because of the Ring,” says Schaub,<br />

who is visibly proud of his team. “If we were a<br />

cable TV channel, we’d be, ‘All Ring, All the Time.’<br />

It’s a core value to our company.”<br />

Finally, the Ring has taught the tech team the<br />

virtues of collaboration: sharing the vision, making<br />

things work, not insisting on your own way.<br />

“We have created an environment where great<br />

ideas flourish,” Schaub explains. “After 21 years,<br />

I’m still excited about the challenge.”<br />

Education is central both to the mission and<br />

future of the company, and here again the<br />

[continued on page 78]<br />

2012/13 SeaSon at <strong>Seattle</strong> opera 71

[continued from page 71]<br />

Ring has been at the heart of <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>’s<br />

community engagement efforts. under two<br />

education directors—the late Perry Lorenzo and<br />

Sue Elliott, Director of Education since 2010—the<br />

company has created Ring-based initiatives for<br />

all ages. Two school <strong>production</strong>s, Theft of the<br />

Gold (2005-08) and its sequel, Siegfried and<br />

the Ring of Fire (2009-11) took the message<br />

of the current <strong>“Green</strong> <strong>Ring”</strong> <strong>production</strong> (man’s<br />

greed destroying the balance of nature) and tied<br />

it in with the school curricula. The shows were<br />

written by Jonathan Dean, currently <strong>Seattle</strong><br />

<strong>Opera</strong>’s Director of Public Programs and Media,<br />

and performed in the schools by members of<br />

the company’s Young Artists Program—and<br />

the young students, who were enthusiastic<br />

Nibelungs and Valkyries.<br />

“Once you tell 10-year-old girls they can be<br />

Valkyries,” Dean quips, “you’re there.”<br />

Now a new Ring-inspired education program is<br />

in development (in addition to a very full menu<br />

of symposia and talks and other adult-education<br />

enhancements to the 2013 Ring). Elliott explains<br />

that it’s a community engagement project called<br />

Belonging(s), involving stories about people’s<br />

most precious possession set to music. “Wagner’s<br />

magic ring is an object upon which an entire<br />

world projects its conflicts and history. Drawing<br />

from this inspiration, we’re using stories of our<br />

most precious possessions to create new work<br />

as part of a local, communal arts practice, using<br />

ideas and images from you, your friends, and<br />

your neighbors.”<br />

For younger audiences (K-8), the company is<br />

commissioning three new Our Earth operas<br />

based on concepts from the <strong>“Green</strong> Ring,” with<br />

input from schools’ science, creative writing, and<br />

art classes. The resulting operas can tour with<br />

piano or expand into chamber versions with a<br />

small orchestra (the latter version to be featured<br />

in festivities throughout 2013).<br />

“One barrier for opera is relevance; it is perceived<br />

as ‘long ago and far away.’ We want to change<br />

the perception of what opera can be,” Elliott<br />

notes. “As Wagner wrote: ‘Kinder, schafft<br />

Neues!’—Children, create something new.”<br />

Melinda Bargreen has been writing about the arts<br />

in the Northwest for 36 years and is a freelance<br />

contributor to several national journals and<br />

newspapers.