Atlin-Taku Planning Area Background Report - Integrated Land ...

Atlin-Taku Planning Area Background Report - Integrated Land ...

Atlin-Taku Planning Area Background Report - Integrated Land ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> <strong>Planning</strong> <strong>Area</strong><br />

<strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong>:<br />

An Overview of Natural, Cultural, and<br />

Socio-Economic Features, <strong>Land</strong> Uses<br />

and Resources Management<br />

Prepared by:<br />

Hannah Horn and Greg C. Tamblyn<br />

Prepared for:<br />

Prince Rupert Interagency<br />

Management Committee<br />

Smithers, B.C<br />

June 2002

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

The authors would like to thank the many people who provided their knowledge and<br />

expertise to making of this report. In particular, we would like to thank all of the agency<br />

staff who contributed much information and time by providing data, map products, and<br />

reports, contributing local knowledge, or reviewing the document for technical accuracy and<br />

completeness. Thanks also to the GIS people at Ministry of Environment, <strong>Land</strong>s and Parks,<br />

who prepared the maps.<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

LIST OF TABLES...............................................................................................................................................V<br />

LIST OF MAPS ................................................................................................................................................. VI<br />

LIST OF ACRONYMS....................................................................................................................................VII<br />

1.0 INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE............................................................................................................1<br />

2.0 THE ATLIN TAKU PLAN AREA ..............................................................................................................1<br />

2.1 THE BIOPHYSICAL SETTING .........................................................................................................................1<br />

2.1.1 Geography and climate.......................................................................................................................1<br />

2.1.2 Ecosystem classification .....................................................................................................................2<br />

2.2 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DESCRIPTION.........................................................................................................5<br />

2.2.1 History of the area ..............................................................................................................................5<br />

2.2.2 Communities .......................................................................................................................................7<br />

2.2.3 Economy and employment ..................................................................................................................8<br />

2.2.4 First Nations .....................................................................................................................................14<br />

2.2.5 Local government and community representation ............................................................................18<br />

3.0 RESOURCE DESCRIPTION AND VALUES..........................................................................................19<br />

3.1 BEDROCK GEOLOGY ..................................................................................................................................19<br />

3.2 VEGETATION ECOLOGY .............................................................................................................................22<br />

3.2.1 Overview of ecosystems ....................................................................................................................22<br />

3.2.2 Forest Types......................................................................................................................................23<br />

3.2.3 Rare ecosystems................................................................................................................................25<br />

3.3 TERRESTRIAL WILDLIFE ............................................................................................................................25<br />

3.3.1 Assessing habitat values....................................................................................................................26<br />

3.3.2 Wildlife species at risk in the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> planning area ...................................................................28<br />

3.3.3 Other species of interest....................................................................................................................32<br />

3.3.4 Current wildlife management strategies ...........................................................................................34<br />

3.4 FRESHWATER FISH.....................................................................................................................................36<br />

4.0 RESOURCE USES......................................................................................................................................40<br />

4.1 CULTURE AND HERITAGE...........................................................................................................................40<br />

4.1.1 First Nations cultural heritage resources .........................................................................................40<br />

4.1.2 Non-aboriginal historic features.......................................................................................................42<br />

4.1.3 Strategic planning considerations related to cultural and heritage resources .................................43<br />

4.2 FORESTRY..................................................................................................................................................43<br />

4.2.1 Timber allocation and harvest ..........................................................................................................43<br />

4.2.2 Timber harvesting and operability....................................................................................................44<br />

4.2.3 Agents of change...............................................................................................................................45<br />

4.2.4 Forest management for biodiversity and wildlife..............................................................................45<br />

4.2.5 Strategic planning considerations related to forestry.......................................................................46<br />

4.3 MINERAL AND ENERGY RESOURCES...........................................................................................................46<br />

4.3.1 Metallic mineral resources ...............................................................................................................46<br />

4.3.2 Placer Resources ..............................................................................................................................56<br />

4.3.3 Industrial Mineral Resources............................................................................................................59<br />

4.3.4 Energy resources ..............................................................................................................................60<br />

4.3.5 Strategic planning considerations related to mineral and energy resources....................................60<br />

4.4 RECREATION, TOURISM AND VISUAL QUALITY .........................................................................................61<br />

4.4.1 Recreational activities and areas of use ............................................................................................61<br />

4.4.2 Tourism .............................................................................................................................................64<br />

4.4.3 Visual quality ....................................................................................................................................67<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page iii

4.4.4 Strategic planning considerations related to recreation, tourism, and visual quality ......................67<br />

4.5 FISHING......................................................................................................................................................68<br />

4.5.1 First Nations Fishery ........................................................................................................................69<br />

4.5.2 Recreational Fishery.........................................................................................................................69<br />

4.5.3 Commercial Fishery..........................................................................................................................70<br />

4.5.4 Strategic planning considerations related to fishing ........................................................................70<br />

4.5.5 Current or upcoming projects...........................................................................................................71<br />

4.6 HUNTING, GUIDE-OUTFITTING AND TRAPPING...........................................................................................71<br />

4.6.1 Hunting .............................................................................................................................................71<br />

4.6.2 Guide-outfitting.................................................................................................................................74<br />

4.6.3 Trapping............................................................................................................................................74<br />

4.6.4 Strategic planning considerations related to the harvest of wild animals. .......................................75<br />

4.7 AGRICULTURE AND CROWN RANGE...........................................................................................................76<br />

4.7.1 Overview of agriculture and Crown range use.................................................................................76<br />

4.7.2 Strategic planning considerations related to agriculture and ranching ...........................................77<br />

4.7.3 Inventory needs .................................................................................................................................77<br />

4.8 FRESHWATER USE ......................................................................................................................................77<br />

4.8.1 Overview of freshwater use...............................................................................................................77<br />

4.8.2 Strategic planning considerations related to water ..........................................................................78<br />

4.9 ROADED ACCESS........................................................................................................................................78<br />

4.9.1 Public roads......................................................................................................................................78<br />

4.9.2 Non-status roads ...............................................................................................................................79<br />

4.9.3 Mineral Resource Access ..................................................................................................................79<br />

4.9.4 Strategic planning considerations related to access.........................................................................81<br />

5.0 PROTECTED AREAS................................................................................................................................83<br />

5.1 EXISTING PROTECTED AREAS ....................................................................................................................83<br />

5.2 PROTECTED AREAS STRATEGY STUDY AREAS ...........................................................................................84<br />

5.3 STRATEGIC PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS RELATED TO PROTECTED AREAS ...............................................88<br />

6.0 HISTORY OF PLANNING IN THE ATLIN-TAKU AREA...................................................................89<br />

7.0 REFERENCES CITED...............................................................................................................................93<br />

7.1 LITERATURE SOURCES ...............................................................................................................................93<br />

7.2 PERSONAL COMMUNICATION .....................................................................................................................97<br />

APPENDIX 1: SUMMARY OF CURRENT RESEARCH AND INVENTORY PROJECTS IN THE<br />

ATLIN-TAKU PLANNING AREA. .................................................................................................................98<br />

APPENDIX 2: RARE AND ENDANGERED PLANT AND ANIMALS SPECIES....................................99<br />

APPENDIX 3: CURRENT POLICY FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT TO MEET BIODIVERSITY<br />

OBJECTIVES...................................................................................................................................................106<br />

APPENDIX 4: PROTECTED AREAS STRATEGY GAP ANALYSIS.....................................................108<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page iv

LIST OF TABLES<br />

Table 1. Ecoregion zones within the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area. .................................................... 3<br />

Table 2. Economic statistics for the Stikine Region Census Subdivision, 1996 ..................... 9<br />

Table 3. Experienced labour force by industry – Stikine Region Census Subdivision, 1996 10<br />

Table 4. Biogeoclimatic subzones and variants in the forested landbase.............................. 22<br />

Table 5. Mammals and birds at risk in the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> planning area. .................................. 29<br />

Table 6. Population estimates for large mammals in management units (MUs) which overlap<br />

the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> planning area. ......................................................................................... 30<br />

Table 7. Economically, culturally or regionally important fish species ................................ 37<br />

Table 8. Small Business Forest Enterprise Program timber sales 1997 – 2000 .................... 44<br />

Table 9. Past Producing Hardrock Mines in the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area................................. 49<br />

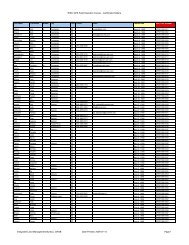

Table 10. Recent Mineral Exploration reporting Expenditures in excess of $20,000 for<br />

Assessment on Mineral Tenures (1994 - 1999) .............................................................. 52<br />

Table 11. Developed hardrock mineral prospects in the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area ..................... 55<br />

Table 12. Industrial mineral prospects in the <strong>Atlin</strong> <strong>Taku</strong> plan area....................................... 60<br />

Table 13. Public recreation activities in the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> area (from Davies, 1999)............... 61<br />

Table 14. Recreation sites and trails in the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area.......................................... 63<br />

Table 15. Days hunted and number of kills (in parentheses) for the main big game species<br />

hunted in the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area (MUs 6-26, 6-26, 6-27, 6-28, 6-29)........................ 73<br />

Table 16. The six most commonly trapped furbearer species in the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area<br />

from 1989 to 1998........................................................................................................... 75<br />

Table 17. Existing parks and protected areas within the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area. .................... 84<br />

Table 18. Summary of the gap analysis by ecosection for the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area. ........... 85<br />

Table 19. Goal 1 PAS study areas within the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area...................................... 86<br />

Table 20. Goal 2 PAS study areas within the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area...................................... 87<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page v

LIST OF MAPS<br />

Map 1: Base map<br />

Map 2: <strong>Land</strong>sat image<br />

Map 3: Biogeoclimatic zones and ecosections<br />

Map 4: Current land status<br />

Map 5: First Nations traditional territories<br />

Map 6: Salmonid habitat<br />

Map 7: Forested landbase<br />

Map 8: Timber harvesting feasibility<br />

Map 9: Logging history<br />

Map 10: Metallic mineral assessment: provincial ranking<br />

Map 11 Industrial mineral assessment: provincial ranking<br />

Map 12: Recorded mineral activity<br />

Map 13: Tourism use areas<br />

Map 14: Guide outfitter territories<br />

Map 15: Protected <strong>Area</strong>s Strategy study areas<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page vi

LIST OF ACRONYMS<br />

AAC Allowable Annual Cut<br />

ALR Agricultural <strong>Land</strong> Reserve<br />

AOA Archaeological Overview Assessment<br />

BEC Biogeoclimatic Ecosystem Classification<br />

BEI Broad Ecosystem Inventory<br />

BEU Broad Ecosystem Unit<br />

C-AFN Champagne-Aishihik First Nations<br />

CMTs Culturally modified trees<br />

COSEWIC Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada<br />

CWD Coarse woody debris<br />

CWS Canadian Wildlife Service<br />

DFO Fisheries and Oceans Canada<br />

FPC Forest Practices Code<br />

IWMS Identified Wildlife Management Strategies<br />

LRMP <strong>Land</strong> and Resource Management Plan<br />

MELP Ministry of Environment, <strong>Land</strong>s and Parks<br />

MOF Ministry of Forests<br />

MoTH Ministry of Transportation and Highways<br />

MSBTC Ministry of Small Business, Tourism, and Culture<br />

MU Management Unit (for wildlife)<br />

NDT Natural Disturbance Type<br />

PAS Protected <strong>Area</strong>s Strategy<br />

RIC Resources Inventory Committee<br />

RPAT Regional Protected <strong>Area</strong>s Team<br />

TOS Tourism Opportunity Study<br />

TRT <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit<br />

TSA Timber Supply <strong>Area</strong><br />

TSR Timber Supply Review<br />

TUS Traditional Use Study<br />

VQO Visual Quality Objective<br />

WHA Wildlife Habitat <strong>Area</strong><br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page vii

LIST OF ACRONYMS CONTINUED<br />

Biogeoclimatic subzones:<br />

AT Alpine Tundra<br />

BWBSdk1 Boreal White and Black Spruce dry cool<br />

BWBSund Boreal White and Black Spruce undifferentiated<br />

BWBSvk Boreal White and Black Spruce very wet cool<br />

CWHwm Coastal Western Hemlock wet maritime<br />

ESSFvc Engelmann Spruce - Subalpine Fir very wet cold<br />

MHund Mountain Hemlock (undifferentiated)<br />

SBSund Sub-Boreal Spruce (undifferentiated)<br />

SWBdk Spruce-Willow-Birch dry cool<br />

SWBund Spruce-Willow-Birch undifferentiated<br />

SWBvk Spruce-Willow-Birch very wet cool<br />

Ecosections:<br />

ALR Alsek Ranges<br />

BOR Boundary Ranges<br />

ICR Icefield Ranges<br />

STP Stikine Plateau<br />

TAB Tatsenshini Basin<br />

TAH Tagish Highland<br />

TEB Teslin Basin<br />

TEP Teslin Plateau<br />

THH Tahltan Highland<br />

TUR Tuya Ranges<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page viii

1.0 INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE<br />

This background report provides an overview and summary of information describing the<br />

natural, cultural, and socio-economic features of the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area. The information<br />

in this report is intended to provide government staff with a current picture of the conditions<br />

and characteristics of land use and resource management in the plan area. It will provide the<br />

foundation for a technical document for members of the public, stakeholders and interest<br />

groups in the event of an LRMP process in the North Cassiar.<br />

The key components of the document are:<br />

A description of the plan area, including social, economic, and environmental<br />

attributes;<br />

An overview of resource uses and associated strategic planning considerations;<br />

A description of existing and proposed land management zones, including protected<br />

areas; and<br />

A history of planning in the area<br />

The information shown here is based on data and information from published journals,<br />

books, and government documents, current inventory information, and from discussions with<br />

government staff.<br />

Note: the maps shown in this report are current to 2000 when the initial datasets were<br />

assembled. The information in the report is current to May 2001. It does not incorporate<br />

changes in government structure since the June 2001 provincial election.<br />

Geographic area included in the report<br />

This report provides data and information on the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area (Map 1). The plan<br />

area boundary includes the Canadian portion of the <strong>Taku</strong> and Tatsenshini-Alsek watersheds<br />

and the BC portion of the Teslin and Yukon watersheds. The western boundary of the plan<br />

area adjoins the Alaska Panhandle and the northern boundary follows the border with the<br />

Yukon Territory. The area comprises the northwestern portion of the Cassiar Timber Supply<br />

<strong>Area</strong> (Alsek and <strong>Atlin</strong> Supply Blocks). The total size of the plan area is approximately 5.54<br />

million hectares. Approximately 1505 ha of the plan is private land and another 1300 ha is<br />

Indian reserves.<br />

2.0 THE ATLIN TAKU PLAN AREA<br />

2.1 The Biophysical Setting<br />

2.1.1 Geography and climate<br />

The <strong>Atlin</strong> <strong>Taku</strong> area is geographically complex, extending from the Coast Mountains inland<br />

almost to Watson Lake. The <strong>Land</strong>sat satellite image shown in Map 2 gives and indication of<br />

the geography of the plan area.<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 1

The more coastal areas are characterized by mountainous terrain with fast-moving high<br />

gradient streams, broad river floodplains and massive glacial fields. The climate is dictated<br />

by the topography and proximity to the coast, resulting in heavy precipitation and oceanmoderated<br />

temperatures. The mean monthly temperature at the lower <strong>Taku</strong> River ranges<br />

from – 8°C in the winter to 15°C in the summer. Average annual precipitation is over<br />

2000mm/yr (Rescan, 1997).<br />

The interior part of the plan area is composed of a mixture of low mountains and large<br />

plateaus. The climate in the interior is continental and under an arctic influence. Winters are<br />

long and cold with limited snow accumulation. Summers are brief and warm. In <strong>Atlin</strong>, the<br />

mean temperature in January is -16°C and in July is 12.5°C. Annual precipitation is 338<br />

mm/yr (Rescan, 1997).<br />

As one moves from the coast to the interior, the conditions are transitional. This is reflected<br />

in distinct ecosystems that reflect the transition between the two climatic and physiographic<br />

regimes.<br />

The area contains seven biogeoclimatic zones and ten ecosections (see Section 2.1.2:<br />

Ecosystem Classification). Almost half of the area (43%) is in Alpine Tundra. Major rivers<br />

include the <strong>Taku</strong>, Tatsenshini, and Alsek Rivers. There is a complex of large lakes (<strong>Atlin</strong>,<br />

Tagish, and Teslin Lakes) that feed the Yukon River watershed. Fed by the Llewellyn<br />

Glacier, <strong>Atlin</strong> Lake is the largest natural lake in BC 1 and forms the headwaters of the Yukon<br />

drainage.<br />

2.1.2 Ecosystem classification<br />

Two of the most common methods for describing the ecosystems of British Columbia are the<br />

Biogeoclimatic Ecosystem Classification (BEC) system and the Ecoregion Classification<br />

system. The BEC system (described in Pojar et al., 1987) delineates areas into<br />

biogeoclimatic zones according to climate, elevation, soils and potential climax vegetation 2 .<br />

The <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> LRMP area contains seven biogeoclimatic zones: non-forested Alpine<br />

Tundra (AT), Spruce-Willow-Birch (SWB), Boreal White and Black Spruce (BWBS),<br />

Engelmann Spruce-Subalpine Fir (ESSF), Sub-Boreal Spruce (SBS), Mountain Hemlock<br />

(MH) and Coastal Western Hemlock (CWH) (see Map 3). A more detailed description of the<br />

BEC zones in the plan area is provided in Section 3.2: Vegetation Ecology.<br />

A broader method of describing ecosystems is the ecoregion classification system (described<br />

in Demarchi, 1996). This system is designed to “bring into focus the extent of critical<br />

habitats and their relationship with adjacent areas” (Demarchi et al., 1990). The ecoregion<br />

classification system is hierarchical. The five levels from largest to smallest are as follows:<br />

ecodomains, ecodivisions, ecoprovinces, ecoregions and ecosections. Ecodomains and<br />

ecodivisions are very broad (e.g. four ecodomains are found in B.C.) and place the province<br />

1 Since <strong>Atlin</strong> Lake extends into the Yukon, there are some who contend that it is the second largest natural lake<br />

after Babine Lake in central BC (Davies, 1999).<br />

2 Note: The term “potential climax vegetation” describes the more stable plant communities of later<br />

successional stages. The climax vegetation described for a zone may be different from what is currently<br />

growing on a site.<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 2

in a global context based on broad geographical relationships. The remaining three levels<br />

place the province in context with the rest of the continent or relate areas within the province<br />

to each other. These lower levels divide the province based on areas of similar climate,<br />

physical landscapes and wildlife potential (Meidinger and Pojar, 1991).<br />

The BEC system and Ecoregion Classification system are compatible and are often integrated<br />

for land use planning purposes. For example, the two systems are combined to produce<br />

Broad Ecosystem Classification mapping, also called Broad Ecosystem Inventory. Broad<br />

Ecosystem Classification uses information on dominant vegetation cover or distinct nonvegetation<br />

cover to determine the function and distribution of plant communities in a<br />

landscape. Broad Ecosystem mapping is used to derive interpretive maps of habitat<br />

suitability and capability for wildlife (see Section 3.3.1 Wildlife: Assessing habitat values).<br />

The plan area overlaps with two ecoprovinces, five ecoregions and ten ecosections (Table 1;<br />

Map 3). The ecosection descriptions that follow have been modified from RPAT (1996) and<br />

Demarchi (1996) to provide details specific to the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area.<br />

Table 1. Ecoregion zones within the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area.<br />

Ecoprovince Ecoregion Ecosection<br />

Coast and<br />

Mountains<br />

Northern Boreal<br />

Mountains<br />

Ecoprovince<br />

Northern Coast and<br />

Mountains<br />

Boreal Mountains<br />

and Plateaus<br />

Southern Yukon<br />

Lakes<br />

ALR (Alsek Ranges)<br />

BOR (Boundary Ranges)<br />

STP (Stikine Plateau)<br />

TEP (Teslin Plateau)<br />

TUR (Tuya Ranges)<br />

TEB (Teslin Basin)<br />

St. Elias Mountains ICR (Icefield Ranges)<br />

Yukon-Stikine<br />

Highlands<br />

TAB (Tatshenshini Basin)<br />

TAH (Tagish Highland)<br />

THH (Tahltan Highland)<br />

Alsek Ranges Ecosection (ALR): The Alsek Ranges Ecosection is comprised of the<br />

isolated, rugged ice-capped mountains of the southern Alsek and Fairweather Ranges of the<br />

St Elias Mountains and the northern Boundary Ranges, east of the Chilkat River. The<br />

climate is cold, wet and windy. Precipitation is heavy and winter snows are deep and wet.<br />

This is the smallest and most northerly of the ecosections in the Northern Coast and<br />

Mountains Ecoregion.<br />

Boundary Ranges Ecosection (BOR): This narrow ecosection hugs the eastern side of the<br />

Alaskan panhandle. The area is characterized by glacier-capped granitic mountains and is<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 3

dissected by the wide braided channels and extensive floodplains of the <strong>Taku</strong> and Whiting<br />

rivers.<br />

Icefield Ranges (ICR): The Icefields Ranges Ecosection consists of ice-capped, rugged<br />

mountains comprising the southern extension of the St. Elias Mountains.<br />

Stikine Plateau (STP): The Stikine Plateau Ecosection is an area of rolling plateau ranging<br />

from lowland to alpine. Sedimentary and volcanic rocks underlie the area. The climate is<br />

relatively dry and cold, with lower snow depths than surrounding areas. Low elevations in<br />

the Nahlin River valley are among the driest areas in the Boreal Mountains and Plateaus<br />

Ecoregion.<br />

Tagish Highland (TAH): The Tagish Highland Ecosection is a mountainous area of<br />

intermediate relief between the Teslin Plateau and the Coast Mountains. This transition belt<br />

has numerous gently sloping uplands dissected by rivers that feed into the long linear lakes of<br />

the Teslin Plateau. Although this ecosection is in the rain shadow of the Coast Mountains, it<br />

has greater precipitation than the plateaux to the east. All streams in this ecosection drain<br />

into the upper Yukon River system. Barren alpine areas and snowfields are common.<br />

Tahltan Highland (THH): This ecosection contains the eastern slopes of the Boundary<br />

Ranges. It is a transitional mountain area with several large valleys exposed to the coast that<br />

allow moist air to dominate the lower slopes. There is extensive glaciation proximal to the<br />

Boundary Ranges.<br />

Tatshenshini Basin (TAB): The Tatshenshini Basin is an area of rounded, subdued<br />

mountains and wide valleys leeward of the jagged Boundary and St. Elias Ranges. In spite of<br />

its close proximity to the Pacific Ocean, this area has a typically sub-arctic climate - cold and<br />

comparatively dry for the region. Most of the ecosection is part of the Tatshenshini/Alsek<br />

drainage basin, with the exception of the Kelsall River which flows south to the Chilkat<br />

River.<br />

Teslin Basin (TEB): The Teslin Basin Ecosection consists of a wide valley with several<br />

large lakes, extensive wetlands, isolated mountains and rolling uplands occurring along the<br />

margins. The climate is cold and relatively dry. This ecosection was identified in 1995;<br />

prior to this time, it was included within the Teslin Plateau Ecosection.<br />

Teslin Plateau (TEP): The Teslin Plateau Ecosection is an area of wide valleys and rolling<br />

plateaux. This ecosection, within the Coast Mountains rain shadow, has a dry, subarctic<br />

climate. <strong>Atlin</strong> Lake and part of the <strong>Taku</strong> River are contained within this ecosection.<br />

Tuya Ranges (TUR): This ecosection contains the most widespread rolling alpine landscape<br />

in British Columbia: the northern Stikine Ranges of the Cassiar Mountains, the Kawdy<br />

Plateau, Astutla Range and small portions of the Nisutline and Dease Plateaus. The<br />

distinguishing feature of these ranges is the occurrence of flat-topped, steep-sided volcanoes,<br />

called tuyas that formed during eruptions under Pleistocene glaciers. Little boreal forest is<br />

found within this ecosection because of the relatively high elevation of the valley-bottoms -<br />

100 to 300 meters higher than in the Cassiar Ranges.<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 4

2.2 Social and Economic Description<br />

2.2.1 History of the area<br />

Much of the plan area is within the traditional territory of two Inland Tlingit groups: the <strong>Taku</strong><br />

River Tlingit and Teslin Tlingit First Nations. The Inland Tlingit are of coastal <strong>Taku</strong> Tlingit<br />

ancestry. With the retreat of the <strong>Taku</strong> Glacier from across the <strong>Taku</strong> River, the Tlingit began<br />

travelling up the river and into the <strong>Atlin</strong> Lake area to trade with the interior Athapascan<br />

people. Trade between the Athapascans and the Tlingit was well established by the arrival of<br />

the first Europeans in the late 1700s (Staples and Poushinksy, 1997). As sea otter harvests<br />

declined on the coast and the fur trade with Europeans expanded in the interior, some of the<br />

Tlingit moved away from the coast and settled in the upper <strong>Taku</strong> and Yukon drainages,<br />

intermarrying with the interior Athapascan people 3 . An extensive trading network remained<br />

active to the turn of the century. Trading routes and camps extended throughout the area<br />

connecting major trade centers in what is now Alaska, northern British Columbia and the<br />

Yukon.<br />

This merging of coastal and inland cultures has resulted in a people with a common territory,<br />

language and culture, who make use of both coastal riverine and interior resources (Rescan,<br />

1997). There is a movement to align all Inland Tlingit groups, including the Teslin Tlingit,<br />

Carcross/Tagish, and <strong>Taku</strong> River people into a single group called Da Kha Kwan, which<br />

reflects the traditional ties between the Inland Tlingit groups. Ties between the Inland<br />

Tlingit and coastal Tlingit remain strong (Rescan, 1997).<br />

Oral history describes how, up until a couple of hundred years ago, the area around <strong>Atlin</strong> was<br />

Tagish territory. The Tagish lands were offered to the <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit as compensation<br />

for the death of a <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit woman. The <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit are also said to have<br />

defeated the Tahltan people in the early 1800s, assuming territorial rights to the upper <strong>Taku</strong><br />

watershed and most of its tributaries (Rescan, 1997).<br />

Explorers, traders and prospectors began visiting the <strong>Taku</strong> region in the late 1700s. The<br />

Hudsons’ Bay company operated a number of trading posts in the area in the mid- late-1800s.<br />

Some placer mining occurred in the 1880s and the <strong>Taku</strong> River was used as an alternative<br />

route to the Klondike during the gold rush of 1898. The Klondike gold rush of 1897 and<br />

1898 brought tens of thousands of people to the north, seeking their riches in the streams<br />

around Dawson City. The Chilkoot Trail and White Pass route were two of the main routes<br />

to the Klondike gold fields. Hopeful prospectors were required by the Canadian Royal<br />

Mounted Police to haul one ton of goods over the Chilkoot Pass into British Columbia;<br />

enough food and supplies to support them for one year. Many of the Tagish people acted as<br />

packers for the prospectors on the Chilkoot Trail during the Gold Rush. Most of these<br />

stampeders returned to their homes empty handed, but the frenzied rush from Alaska into the<br />

Yukon has been called one of the last great adventures.<br />

3 There are a number of theories as to why some coastal Tlingit moved and settled inland. These include<br />

population pressure on the coast; benefits of the Interior fur trade; intermarriage; and friendship bonds formed<br />

with trading partners in the Interior (Yukon Community Profile, 2001)<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 5

The <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit, living in semi-permanent camps on the shores of <strong>Atlin</strong> Lake, had<br />

little interaction with non-native outsiders until the discovery of placer gold at Pine Creek in<br />

1898. Thousands of gold seekers flooded into the area, many of them diverted from the<br />

Klondike goldfields. By 1899 there were approximately 1500 people living at the <strong>Atlin</strong><br />

townsite and another 4500 in gold camps at Discovery on Pine Creek. At its peak, there were<br />

approximately 10,000 people in the area (<strong>Atlin</strong> Community Website, 2001). At the time 10<br />

reserves, representing 1300 ha, were established for the <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit (then called the<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-Teslin band). The reserve at Five Mile Point was intended as a relocation site,<br />

although Chief <strong>Taku</strong> Jack rejected the proposed relocation and the TRTFN village was<br />

maintained on non-reserve land (Steele, 1995). By 1907, when gold production tapered off<br />

and mining became less economical, the population of <strong>Atlin</strong> had dropped to a few hundred<br />

and Discovery virtually ceased to exist.<br />

Mining has continued to be one of the primary economic mainstays of the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> area<br />

through the years. Many of the creeks around <strong>Atlin</strong> have past or existing placer operations<br />

on them, with placer mines ranging in size from single person outfits to large operations<br />

using heavy equipment and employing several people. The <strong>Atlin</strong> area has yielded over $23<br />

million in gold in the last 100 years, second only to the Cariboo for placer gold production in<br />

BC (BC Tour Online, 2000). There have been a number of mining operations on the <strong>Taku</strong><br />

River since the 1800s. Mines have operated at three deposits along the Tulsequah River<br />

(Tulsequah Chief, Big Bull, and Polaris <strong>Taku</strong>) at various times between 1923 and 1957. In<br />

1929, the small settlement of Tulsequah was established as a service center for three<br />

operating mines, all of which ceased production at the outbreak of World War 2. The<br />

Tulsequah Chief mine re-opened after the war and closed again in 1957. Redfern Resources<br />

Ltd. began an application to resume operations at the Tulsequah Chief mine in 1994. A<br />

Project Approval Certificate for the project was granted in 1998 following a two and a half<br />

year review under the Environmental Assessment Act. However, the decision to grant the<br />

Certificate was overturned in June 2000 by Supreme Court of BC as the result of a lawsuit<br />

launched by the <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit. This project remains under review by the Environmental<br />

Assessment Office.<br />

Tourism is also a longstanding contributor to the <strong>Atlin</strong> economy. Following the gold rush in<br />

1898, <strong>Atlin</strong> became a fashionable place to visit for American tourists on their Alaskan tour.<br />

Cruise ships brought passengers from Seattle and San Francisco to Skagway, where they<br />

disembarked and boarded the White Pass rail to Carcross. They then transferred to a paddle<br />

steamer on Tagish Lake and headed to <strong>Taku</strong> <strong>Land</strong>ing, and from there to <strong>Atlin</strong>. The M.V.<br />

Tarahne, built in 1917, took passengers on tours of <strong>Atlin</strong> Lake. In the early 1900s, at the<br />

peak of tourism for that period, 400 people per week made the journey to <strong>Atlin</strong> (<strong>Atlin</strong><br />

Community Website, 2001). These overland excursions to <strong>Atlin</strong> ended in the 1930s when<br />

airplanes began to service <strong>Atlin</strong> and the White Pass rail company withdrew its transportation<br />

link to the area. Tourism has continued to provide local employment, primarily in the<br />

summer months.<br />

World War II hit the mining and tourism industries in <strong>Atlin</strong> and area hard. Jobs disappeared<br />

and the population of <strong>Atlin</strong> dwindled. The <strong>Atlin</strong> Road was built in 1949-50 linking <strong>Atlin</strong> to<br />

the Alaska Highway. Despite the land-based link to Whitehorse and beyond, the size of the<br />

town was slow to recover. In 1963, the non-aboriginal population of <strong>Atlin</strong> was only 75<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 6

(Rescan, 1997). In the 1960s the overall population of the town slowly began to rise again as<br />

people began moving into the area as part of a lifestyle choice. The current population of<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong> is approximately 450 permanent residents and 100 – 200 seasonal residents (<strong>Atlin</strong><br />

Community Website, 2001).<br />

2.2.2 Communities<br />

The population of the northern BC is characterized by small, unincorporated communities<br />

separated by long distances and the plan area is no exception. In 1996, the total population<br />

for the Stikine Region Census Subdivision, which covers 11 million ha and includes the<br />

communities of <strong>Atlin</strong>, Dease Lake, Good Hope Lake and Lower Post, was only 1391 (BC<br />

Stats, 2001). Other than small and scattered settlements, the only sizable community and<br />

commercial centre in the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area is the town of <strong>Atlin</strong> on the eastern shores of<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong> Lake. Map 4 summarizes the current land status of the plan area.<br />

2.2.2.1 <strong>Atlin</strong><br />

Set on an aquamarine glacier-fed lake with a panoramic view of the rugged peaks of the<br />

Coast Mountains and steeped in history and pre-history, <strong>Atlin</strong> is a community that imparts a<br />

strong sense of place and character. The name <strong>Atlin</strong> comes from a Tlingit work “Ah-tlen”<br />

meaning “big waters”. The number of year-round residents in the town is currently around<br />

450, increasing by 100 - 200 in the summer months (<strong>Atlin</strong> Community Website, 2001).<br />

Summer residents include recreational property owners and those with seasonal employment<br />

(primarily placer miners). <strong>Atlin</strong> township is the northern and westernmost town in BC at a<br />

latitude of 59° 35’N and longitude of 133° 40’ W. On the longest day in <strong>Atlin</strong> there are 18<br />

hours and 42 minutes of sunlight. The township is unincorporated and the affairs of the town<br />

are run by voluntary organizations such as the <strong>Atlin</strong> Advisory <strong>Planning</strong> Commission, who<br />

deal with land use planning and application referrals, and the <strong>Atlin</strong> Board of Trade, whose<br />

mandate is to promote economic and social enhancement. Many of the residents of the<br />

community have grown up in <strong>Atlin</strong> or have lived there for a long time. The town is<br />

characterized by its history and surroundings as well as the independent and self-sufficient<br />

spirit of its residents.<br />

Access to <strong>Atlin</strong> is limited. The <strong>Atlin</strong> Road provides the only ground access to the town. The<br />

nearest major center, Whitehorse in the Yukon, is approximately 200 km (two hours drive)<br />

away. A local bus and van service provides public transportation between <strong>Atlin</strong> and<br />

Whitehorse (population 22,000 in 1996). Fixed wing planes, float planes and helicopters<br />

provide year round flights to the town. Juneau, Alaska, is 45 minutes from <strong>Atlin</strong> by air.<br />

Skagway, Alaska, is also accessible by a short plane ride. <strong>Atlin</strong> can be accessed by boat from<br />

the town of Tagish along Tagish Lake in the Yukon. In the winter months, when the lakes<br />

have frozen, travel to the area can also occur by snowmobile and dog-sled.<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong> has a number of amenities including a recreation center and curling rink, two general<br />

stores, a post office, a community library, an airport, an RCMP station, a fire department and<br />

a Red Cross Outpost Hospital. There are limited banking services through the Government<br />

Agent and Bank of Montreal. The Government Agent acts as liaison to other provincial<br />

departments and offers a wide range of services to the town including: mining recording;<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 7

court register; issuing of birth, death and marriage certificates; Hunting and Fishing<br />

Licences; and Notary Public (Government Agents website, 2001).<br />

The local school goes from kindergarten to Grade 9. Grades 10 – 12 and adult education<br />

classes are provided through a pathfinder lab (distance education). Many students complete<br />

their Grade 10 – 12 years in Whitehorse. The <strong>Atlin</strong> School operates a satellite outreach<br />

program for children in outlying areas and one teacher travels over a large area to tutor these<br />

students.<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>’s power is supplied by a diesel generation plant with five diesel generators. Fuel to run<br />

the generators (1.2 million liters/year) has to be trucked in via the <strong>Atlin</strong> Road (Rescan, 1997).<br />

Most of drinking water for the town is taken from <strong>Atlin</strong> Lake.<br />

2.2.2.2 First Nations communities<br />

Approximately one-quarter of the 360 members of the <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit live in or near<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong> (INAC, 2001; Staples and Poushinsky, 1997). Most homes are on the Five Mile Point<br />

Indian Reserve No. 3 about 8 km south of <strong>Atlin</strong>. A small number of households and the<br />

TRTFN administration office are located on Indian Reserve No. 4 (‘townsite reserve) within<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>. A few families also live off-reserve in <strong>Atlin</strong> and in other communities in the Yukon<br />

and BC. Members of the Tlingit community living away from <strong>Atlin</strong> travel frequently to the<br />

area to visit relatives and to hunt, fish and gather berries and medicinal plants in the TRTFN<br />

traditional territory (Rescan, 1997).<br />

Although the Champagne-Aishihik, Carcross/Tagish, and Teslin Tlingit First Nations have<br />

traditional territories over large parts of the plan area, their communities are all in the Yukon.<br />

2.2.3 Economy and employment<br />

The economy of the plan area is largely seasonal. With the exception of a small heli-skiing<br />

operation, most local businesses are summer operations such as mining, tourism, home<br />

building, road construction, commercial fishing and guide outfitting. Most of the year round<br />

employment is based in <strong>Atlin</strong> in government jobs (First Nations, provincial and federal) and<br />

with providers of goods and services. The unemployment rate in the winter months is<br />

generally high.<br />

In the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> area, as is the case for other northern communities, the cost of living is<br />

high due to the distance from markets and the low volume of sales. Residents of <strong>Atlin</strong> tend<br />

to travel to shop, bank, use services, and enjoy social amenities unavailable in their own<br />

town. This results in a leakage of dollars out of the community and into the larger center.<br />

Many of the residents engage in sustenance hunting, fishing, and gathering activities. For<br />

many local residents, particularly the <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit, hunting, trapping, fishing, and<br />

berry-picking provide are integral to the social and cultural fabric of the community and are a<br />

significant component of the local economy (Staples and Poushinsky, 1997).<br />

Economic activity in the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> area is constrained by its limited infrastructure and long<br />

distance to markets. The main economic drivers, mining and tourism, are cyclical in nature<br />

which has lead to significant fluctuations in the local economy.<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 8

Table 2 summarizes employment statistics for the Stikine Region Census Subdivision, which<br />

includes <strong>Atlin</strong>, Dease Lake, Good Hope Lake, and Lower Post. Statistics were not available<br />

for the town of <strong>Atlin</strong> itself. The population of the overall Stikine Region covering 13 million<br />

hectares, was only 1391 in 1996 (Statistics Canada, 2001). Of these, the participation rate in<br />

the labour force is somewhat higher than the provincial average, although the average<br />

household income is lower than the average for BC. Approximately 14% of the workers in<br />

the Stikine Region worked away from home, with most working outside of the Stikine<br />

Region itself (Statistics Canada, 2001)<br />

Table 2. Economic statistics for the Stikine Region Census Subdivision, 1996<br />

Stikine Region B.C.<br />

Population 1391 3,724,500<br />

Pop (15+) in labour force 780 1,960,660<br />

Participation rate (%) 74.3 66.4<br />

Unemployment Rate (%) 9.6 9.6<br />

Average household<br />

income (1995)<br />

Sources: Statistics Canada, 2001<br />

41,893 50,667<br />

Table 3 summarizes the experienced labour force by industry in the Stikine Region Census<br />

Subdivision in 1996. While this profile is for a much larger area, including the towns of<br />

Dease Lake, Good Hope Lake and Lower Post, it provides an overview of the general<br />

employment in the northwest. As shown in Table 3, the public sector (government,<br />

education, health and social services) is the largest employer, representing 42% of the<br />

experienced labour force. Mining represents the highest non-government employer at 10%.<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 9

Table 3. Experienced labour force by industry – Stikine Region Census Subdivision, 1996<br />

Industry divisions 1996 labour force % of 1996 labour<br />

force<br />

Agriculture and related services 20 2<br />

Fishing and trapping 10 1<br />

Logging and forestry 20 2<br />

Mining and milling, quarrying<br />

and oil well<br />

80 10<br />

Manufacturing 10 1<br />

Construction 45 5<br />

Transportation and storage 20 2<br />

Retail trade 70 9<br />

Business services 10 1<br />

Government services 175 22<br />

Educational services 140 18<br />

Health and social services 20 2<br />

Accommodation, food and<br />

beverage<br />

75 9<br />

Other service industries 60 7<br />

Total labour force 15 yrs+ 775 100<br />

2.2.3.1 Mining<br />

The town of <strong>Atlin</strong> was built on placer mining and it remains a key employer in the<br />

community. Hardrock mining has been a lesser contributor to the local economy, as past<br />

producing mines adjacent to the community have been small with short periods of operation.<br />

However, hardrock mineral exploration continues to contribute to the local economy, through<br />

seasonal employment and purchase of local goods and services.<br />

In the broader plan area, there are several significant past producing mines and mineral<br />

exploration that, as a result of topography and infrastructure, have benefited northern<br />

residents outside of the <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area. Examples include intensive exploration and<br />

development of the Windy-Craggy deposit in the Tatsenshini-Alsek park area, historic<br />

mining of the Tulsequah and Polaris-<strong>Taku</strong> deposits in the <strong>Taku</strong> River area and recent mining<br />

at the Golden Bear deposit, located north of Telegraph Creek.<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 10

Placer gold mining<br />

Though many of the streams have been panned for gold, placer gold production has been<br />

concentrated in two relatively small portions of the plan area. Placer gold production from<br />

streams in the St. Elias Mountains ended prior to 1993, when establishment of the<br />

Tatshenshini-Alsek Park absorbed active placer areas. The remaining placer gold production<br />

area is located proximal to the community of <strong>Atlin</strong>.<br />

Many of the creeks lying to the east and south of <strong>Atlin</strong>, contain placer gold and are actively<br />

mined. Placer mining largely occurs outside of the winter months, though in some years, a<br />

few operations continue year round. Winter is also used to mobilize equipment to remote<br />

placer sites, to minimize environmental impacts. Placer mining is considered the most<br />

important contributor to the local economy, generating approximately $5 million in 1994<br />

(Rescan, 1997). In 1996, placer mines employed approximately 150 people a year on a<br />

seasonal basis (approximately one-quarter of the summer population) (Rescan, 1997). The<br />

overall income dependency on mining in <strong>Atlin</strong>, based on the above figures, is estimated at<br />

60% (Rescan, 1997). The economy of the town is tied closely to gold prices and the<br />

economic health of the town tends to fluctuate as markets change (Steele, 1995; <strong>Atlin</strong><br />

Community Website, 2001).<br />

Hardrock mineral development<br />

The <strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> plan area has good potential for the discovery of economic mineral deposits.<br />

The area encompasses one operating mine, several past producing metallic mines, and<br />

numerous developed prospects. Several of the known developed prospects are polymetallic,<br />

containing several potentially economic metals, in addition to the very rich Windy Craggy<br />

copper-deposit. Reflective of the prospective geology in the plan area, is the large number of<br />

mineral tenures and extensive mineral exploration conducted. Exploration spending in the<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong> area alone is estimated at $500,000 to $1 million per year (Rescan, 1997).<br />

Currently, the only operating mine in the plan area, the Golden Bear mine, is near closure.<br />

The mine originally opened in 1989, as an underground and small open pit operation,<br />

processing ore through conventional floatation methods. The processing method proved<br />

uneconomic, leading to closure of the mine in 1994. The mine was subsequently bought by<br />

Wheaton River Minerals, who conducted further exploration and development, which led to<br />

reopening as a heap leach gold operation in 1997. Mining at the site was completed in 2000,<br />

but processing of ore is anticipated to continue to 2002. Since reopening in 1997, the mine<br />

has operated on a seasonal basis, employing approximately 80 persons when actively mining.<br />

Mining and tourism<br />

Mining activity has contributed to the development of tourism in the <strong>Atlin</strong> area both<br />

historically and at the present. In the early 1900's, small communities were established<br />

around the Ben-My-Chree and Engineer mines, on Tagish Lake. At Ben-My-Chree, the wife<br />

of the mine owner developed beautiful gardens and ran a small tourist operation serving tea<br />

for travelers arriving on the paddlewheeler. Both sites continue to be points of interest for<br />

travelers. In the community of <strong>Atlin</strong>, historic placer activity is a draw for tourism. Efforts<br />

have been made to establish a mining museum and develop placer tourism opportunities.<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 11

2.2.3.2 Tourism<br />

As with mining, tourism has a long, cyclical history in the <strong>Atlin</strong> area. The White Pass<br />

railway, built by the Klondike gold rush, provided access to the area until the 1930s,<br />

augmented by boat travel on Tagish and <strong>Atlin</strong> lakes.<br />

Today tourists are drawn to the plan area by the spectacular scenery, history and culture, and<br />

opportunities for quality outdoor experiences in a wilderness setting. Though some winter<br />

tourism has been developed in recent years, most activity is concentrated in the summer<br />

months. Tourism operations are based out of <strong>Atlin</strong>, Whitehorse, and Alaska (Juneau and<br />

Haines). The plan area is not as much of a tourist destination in and of itself, rather it is one<br />

part of an overall northern experience that includes Alaska and the Yukon.<br />

With its large areas of wilderness, most of the tourism operations offered are nature-based<br />

backcountry experiences. There are also more front-country facilities and amenities<br />

available within <strong>Atlin</strong>.<br />

Summer tourism<br />

Most of the tourism activity in the plan area occurs between the months of May and<br />

September. Summer tourism activities are land, air and water-based. <strong>Land</strong>-based tourism<br />

activities include touring, wilderness backpacking, glacier touring, mountaineering, and<br />

guided fishing and big game hunting. In 1999, there were four guiding businesses based in<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong> offering hiking and mountaineering trips and four guide outfitting companies offering<br />

guided hunting, fishing and wildlife viewing opportunities (Davies, 1999). Tourists often<br />

make the detour into <strong>Atlin</strong> as part of their driving tour to and from Alaska.<br />

There are a large number of commercial operators offering a range of motorized and nonmotorized<br />

water-based activities in the <strong>Atlin</strong> area, on the <strong>Taku</strong>, and in Tatsenshini-Alsek<br />

Park. These include houseboat rentals on <strong>Atlin</strong> Lake, sports fishing trips on the <strong>Taku</strong>,<br />

Nakina and Inklin Rivers, guided and non-guided kayaking and canoeing trips on the lakes<br />

near the BC-Yukon border, and guided raft trips down the <strong>Taku</strong>, Tatsenshini, and Alsek<br />

Rivers (Davies, 1999).<br />

Winter tourism<br />

Winter tourism activities include guided heli-skiing, cross-country skiing, snow-mobiling<br />

and dog sledding. Most winter tourism activities are based out of <strong>Atlin</strong>. Winter tourism is<br />

much smaller than summer tourism and local tourism interests feel that there is potential for<br />

expansion of the winter tourism market (Rescan, 1997).<br />

Air-based tourism<br />

In 1999, three air charter operations offered sightseeing from either fixed wing or float<br />

planes. In addition, one business offers helicopter sightseeing and heliskiing (Davies, 1999).<br />

Air transportation is available throughout the year.<br />

2.2.3.3 Commercial fishing<br />

The only commercial fishery in the plan area is on the lower <strong>Taku</strong> River. There are eighteen<br />

commercial gillnet licenses in the Canadian fishery on the <strong>Taku</strong> River. The TRTFN holds<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 12

eight licences. The other licences are held by residents of <strong>Atlin</strong> or elsewhere (J. Burdek, pers<br />

comm.; RES, 1997).<br />

Most fish are flown to <strong>Atlin</strong> for processing or freezing, although some are sold in Juneau or<br />

flown to <strong>Atlin</strong> for retail sale. There is one processing plant in <strong>Atlin</strong> that produces smoked<br />

salmon products. Some TRTFN fishermen also sell a portion of their catch as smoked<br />

products (Rescan, 1997).<br />

2.2.3.4. Forestry<br />

There is currently little forestry activity in the plan area. Much of the area is classified as<br />

inoperable. The average annual timber harvest in the operable areas ranges from 1500 - 2000<br />

m 3 /yr, primarily to provide timber for local home building, mine timbers and rough cut<br />

timber. The amount allocated for harvesting is in response to local demand and is unlikely to<br />

change significantly in the near future (C. Rygaard, pers. comm.). Over time, timber is<br />

becoming less accessible and is located farther from the community..<br />

There are no major forest tenures in the area. Deterrents to large-scale timber development<br />

include the high cost of operations (due to the relatively low volumes and inaccessibility of<br />

merchantable timber), long distances to processing facilities and markets, a lack of local<br />

infrastructure, and a low and cyclical demand for timber locally. To date, Crown timber has<br />

only been offered only as short-term sales under the Small Business Forest Enterprise<br />

Program and through the Forest Service Reserve. About 8 - 12 people are employed in<br />

timber harvesting and silviculture activities on an annual basis (C. Rygaard, pers comm.).<br />

There are a number of small family-owned mills in the <strong>Atlin</strong> area, including a mill owned<br />

and operated by the TRTFN and located on the Five Mile reserve (Rescan, 1997). Most<br />

timber is sold and used locally.<br />

2.2.3.5 Trapping<br />

Trapping provides seasonal income for a number of local residents, including a number of<br />

<strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit. Not all of the traplines in the area are active. The number of individual<br />

species trapped is dependent on influenced by furbearer numbers and market prices. Marten<br />

are the most frequently trapped species.<br />

2.2.3.6 Agriculture and range<br />

A number of people in the <strong>Atlin</strong> area grow local produce for sale in Whitehorse and in <strong>Atlin</strong><br />

itself. There are also a number of agricultural leases and tenures for beef production. Guide<br />

outfitters in the area have range tenures for grazing of packhorses.<br />

2.2.3.7 Other economic activities<br />

Artisans<br />

There are a number of home-based artist studios in <strong>Atlin</strong>, many of them selling arts and crafts<br />

made from local materials. An art school and artist’s retreat holds workshops throughout the<br />

summer and attracts participants from around the world.<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 13

Road construction and maintenance<br />

The maintenance and construction of highways is contracted to a private company, providing<br />

both seasonal and year-round employment. In addition, a number of small operators in <strong>Atlin</strong><br />

have equipment that can be used in road construction.<br />

2.2.4 First Nations<br />

There are five First Nations groups with an interest in the plan area: the <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit<br />

First Nation, Tlingit Teslin Council, Carcross/Tagish First Nation, Tahltan First Nation, and<br />

Champagne-Aishihik First Nations (Map 5). The traditional territories of four of these First<br />

Nations are transboundary, extending from BC into the Yukon and, in some cases, into<br />

Alaska.<br />

The <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit and Teslin Tlingit are closely related, sharing a common history,<br />

culture and language. The First Nations communities at <strong>Atlin</strong> and Teslin are connected<br />

through a system of trails that were used extensively until the 1940s when the Alaska<br />

Highway was built (Yukon Community Profiles, 2001). The ties between the two Inland<br />

Tlingit groups, which are closely linked culturally, politically and economically, remains<br />

strong (Staples and Poushinsky, 1997). The introduction of non-Tlingit political and<br />

administrative boundaries (e.g., political boundaries and the registered trapline system) at the<br />

time of European settlement divided traditional Tlingit territories that extended from Alaska<br />

to the Yukon. There is an social division among the Tlingit people that exists to this day<br />

between “BCers” and “Yukoners,” with associated challenges to maintaining the traditional<br />

systems of land ownership and management of resources (Staples and Poushinsky, 1997).<br />

The Carcross/Tagish people are a blend of coastal Tlingit and interior Tagish and Athapaskan<br />

ancestry. Ties between the First Nations communities at Carcross and Tagish and the <strong>Atlin</strong><br />

and Teslin communities are also strong.<br />

The <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit, Telin Tlingit, Carcross/Tagish and Champagne-Aishihik are all at<br />

Stage 4 of the BC Treaty process (negotiation of an agreement-in-principle) and are<br />

negotiating together at the Northern Regional Negotiations table. The Champagne-Aishihik<br />

and Teslin Tlingit have already negotiated agreements on land settlement and selfgovernment<br />

with Canada and the Yukon Territory. These agreements received Royal Assent<br />

in July 1994. The Carcross/Tagish First Nation are currently negotiating their final<br />

agreement on land claims and self-government with the federal and Yukon governments.<br />

The <strong>Land</strong> Claims and Self-Government Agreements assert a role for these First Nations in<br />

co-management of their traditional territorial lands and any development proceeding on those<br />

lands. In accordance with the agreements, regional land use planning processes are<br />

beginning in Yukon portion of the traditional territories of the Champagne and Aishihik First<br />

Nations and the Teslin Tlingit Council. Once the final agreements are settled with the<br />

Carcross/Tagish First Nation, their traditional territories will be incorporated into the Teslin<br />

regional land use planning process, to create a larger Daak Ka planning region in the Yukon.<br />

The Tahltan Nation has withdrawn from the BC Treaty Negotiation process.<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 14

2.2.4.1 <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit<br />

The <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit First Nation (TRTFN) are based out of <strong>Atlin</strong>, although many<br />

members live in communities in the Yukon (Whitehorse, Carcross and Teslin) and in<br />

Vancouver and other parts of BC and the US. There were 361 registered members of the<br />

TRTFN in 2001, 72% of whom lived off reserve (Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 2001)<br />

The traditional territory of the <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit includes the <strong>Taku</strong> River and most of its<br />

tributaries, <strong>Atlin</strong> and Little <strong>Atlin</strong> lakes at the southern end of the Yukon drainage, and large<br />

portions of the interior region in the southern Yukon (Map 5). The TRT have ten Indian<br />

Reserves, all in BC, totaling 1264 ha. Seven of the reserves are around <strong>Atlin</strong> and three are<br />

around Teslin Lake. The <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit is comprised of two clans: the Yanyèdí clan of<br />

the Wolf moiety and the Kùkhhittàn clan of the Crow moiety. The First Nation is governed<br />

under a traditional clan system (see Section 2.2.6: Local Government and Community<br />

Representation).<br />

The economy of the TRTFN communities has been described as a “mixed” economy where<br />

traditional land use (hunting, fishing, berry-picking, etc) and a cash economy (through wage<br />

earning and income from other sources) are combined (Staples and Poushinsky, 1997). This<br />

diversity provides a degree of economic stability, providing a buffer against seasonal changes<br />

in employment and the uncertainties of external economies. Members of the community<br />

work in guiding (fish and game), outfitting, carpentry, mining, commercial fishing, and<br />

casual labouring. The TRTFN has a mill on the No 5 reserve and holds eight commercial<br />

fishing licences on the lower <strong>Taku</strong> River.<br />

Hunting, fishing and gathering of plants for food and medicine are considered integral to the<br />

social, cultural, and economic fabric of the <strong>Taku</strong> River Tlingit community. Almost all<br />

TRTFN households participate in traditional land use activities. <strong>Area</strong>s of particular<br />

significance to the TRTFN include Blue Canyon, the Gladys River to its confluence with the<br />

Nakina River, the O’Donnell River Valley, Kuthai Lake and Silver Salmon River (Staples<br />

and Poushinsky, 1997).<br />

The TRTFN have a number of concerns related to the management of fish and wildlife and<br />

regulation of hunting, trapping and fishing activities in their traditional territory. There is a<br />

history of conflict between the TRTFN and the provincial and federal governments on these<br />

issues (Staples and Poushinsky, 1997). The concerns of the TRTFN are particularly strong<br />

with regard to the management of hunting in areas traditionally used by the Tlingit and close<br />

to their communities, such as Blue Canyon, Surprise Lake, and areas to the east of <strong>Atlin</strong><br />

(Staples and Poushinsky). These issues are discussed in further detail in Section 4.6.1.2:<br />

Hunting – First Nation. The TRTFN and Fisheries and Oceans Canada are partners in a<br />

program to for fish habitat stewardship in an area that includes the <strong>Taku</strong> River watershed and<br />

the <strong>Atlin</strong> Lake area (see Section 4.5: Fishing).<br />

2.2.4.2 Teslin Tlingit<br />

The Teslin Tlingit live in and around the town of Teslin in the Yukon Territory, 183<br />

kilometers from Whitehorse. Teslin village was originally a Tlingit summer campsite. The<br />

<strong>Atlin</strong>-<strong>Taku</strong> Technical <strong>Background</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Page 15

Teslin Tlingit currently comprise approximately two-thirds of the population of Teslin<br />

(Yukon Community Profiles, 2000). The number of members represented by the Teslin<br />

Tlingit Council in 2001 was 536, 52% of whom lived off-reserve. (Indian and Northern<br />

Affairs Canada, 2001).<br />

The traditional territory of the Teslin Tlingit includes the drainage system of Teslin Lake in<br />

northern BC and the southern Yukon (Map 5). All of the Teslin Tlingit reserves are in the<br />

Yukon. The Teslin Tlingit have five clans: Eagle, Wolf, Frog, Crow and Beaver.<br />

The official name of this First Nation is the Teslin Tlingit Council. The Council is<br />

recognized and established under the traditional law of the Teslin Tlingit and is a registered<br />

Indian Band under the Indian Act. The Teslin Tlingit Council is affiliated with the Tlingit<br />

Tribal Council, the Daxa Nation. The Self-Government Agreement signed with the Canada<br />

and the Yukon Territory in 1993 recognizes the Teslin Tlingit Council as a self-governing<br />

First Nation. The clan system has been incorporated into the Council and is an important<br />

aspect of the Self-Government Agreement (Yukon Community Profiles, 2000).<br />

Tle-Nax T-awei Incorporated, the development corporation of the Teslin Tlingit Council, is<br />

involved in a number of community economic initiatives including tourism development, a<br />

small business assistance program, expansion of cultural activities and arts and crafts, and<br />

expansion of the Yukon River Timber Company sawmill (Yukon Community Profiles,<br />

2000). A Teslin Region Tourism Development Plan was developed in 1993. The Plan<br />

identifies a number of opportunities for culturally-based tourism development, including<br />

development of a Teslin Cultural Display to demonstrate the Tlingit culture and northern<br />

lifestyles in general (YFNTA, 2000). The Council is a member of the Yukon First Nations<br />

Tribal Association.<br />

2.2.4.3 Carcross/Tagish<br />

The Carcross/Tagish First Nation (C-TFN) are people of Tlingit, Tagish and Athapaskan<br />

descent. There were 531registered members of the First Nation as of May, 2001, 60% of<br />

whom lived off-reserve (Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 2001). The Carcross/Tagish<br />

people belong to the Tagish linguistic grouping of the Athapaskan language family. Most<br />

live in the communities of Carcross and Tagish and comprise approximately 50% of these<br />

communities (Yukon Community Profiles, 2000). The social organizational system of the<br />

Carcross/Tagish is reflection of their Tlingit and Tagish heritage e.g., with the potlatch being<br />

an important aspect of the social and political fabric of the community. The Carcross/Tagish<br />

have two moieties, crow and wolf, and a number of associated clans.<br />

The traditional territory of the Carcross/Tagish people is primarily located at the headwaters<br />

of the Yukon River system in the Yukon and northwestern BC. The C-TFN is recognized<br />