Clemons and McBeth - MavDISK

Clemons and McBeth - MavDISK

Clemons and McBeth - MavDISK

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

48<br />

Portersville citizens overwhelmingly wanted a primary (basic).healthcare clinic but<br />

only otlethat their smalI community could support without any large increases in taxes.<br />

From the survey <strong>and</strong> focus groups, it was detel'mined that the major evaluation criterion<br />

was .simply cost <strong>and</strong> effectiveness (would the clinic meet the needs of the citizens?).<br />

From this information, the community leaders brainstormed several alternative struc-<br />

tures. Using local building contractors, cost estimates were conducted <strong>and</strong> the pros <strong>and</strong><br />

cons of each design discussed. A medical planning expert was brought in <strong>and</strong> took the<br />

community through a "health care utilization" planning process. This process used the<br />

cOffiII).unity'sage profile from census data to show dem<strong>and</strong> for basic medical services.<br />

This formula predicts the annual number of primary care patients based on a commu-<br />

nity's demograpl1ic profile of age <strong>and</strong> gender. The formula was based on an empirical<br />

analysis of primary health utilization by age groups. For Portersville, the predicted number<br />

of primary care patients per year was 1,339. Using this number, the health care planner<br />

then was able to use another formula to subdivide the categories of likely utilization.<br />

For example, a certain percentage of the primary care visits would be vaccinations, a certain<br />

percentage for flu, <strong>and</strong> a certain percentage for broken bones, <strong>and</strong> so on. The data calculated,<br />

were then multiplied by the fees charged for each type of medical procedure,<br />

producing an estimated annual revenue flow for the proposed clinic. .<br />

With this revenue data in h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> knowing what the county could afford tOisubsidize<br />

in the form of taxes, the planner decided that a much less-expensive <strong>and</strong> elaborate<br />

StrUcture should be built. It was clear that the proposed 4,lOO-square-foot, $750,000 strUc-<br />

ture was weIl beyond the needs <strong>and</strong> resources of Portersville. This rationai<strong>and</strong> empirical<br />

analysis helped the community underst<strong>and</strong> both what PortersvilIe would support financially<br />

<strong>and</strong> the correlated likely dem<strong>and</strong> for services.<br />

The leadership group then engaged in some brainstorming <strong>and</strong> quickly determined<br />

that a simple 2,500-square-foot customized house could easily serve the community's<br />

health care needs. So, the two options now on the table were as follows:<br />

Option #1: A 4,100-square-foot building at a cost of $750,000<br />

Option #2: A customized house converted into a health clinic at around $100,000 in costs<br />

Health care experts <strong>and</strong> community physicians all agreed that the customized house<br />

wouldmakean effectivehealth clinic. The costs were easily absorbedby the.community<br />

<strong>and</strong>by the county'sexisting tax base.<br />

This case is a good example of the usefulness of the rational model. The $750,000 build-<br />

ing fi~t proposed by the architect could easily have destroyed the community's chances of getting<br />

a health care clinic. In retrospect, it is easy to see that the $750,000 building was not going<br />

:0 work in such a small community. But community leaders were excited about the elaborate<br />

iesign <strong>and</strong> the prospect of having such a facility in their town. Without rational analysis, the<br />

lttempt to sell this StrUctureto the community would have failed miserably, <strong>and</strong> if the building<br />

lad been built it would have been underutilized-a white elephant sitting mostly unused. The<br />

:urveys, focus groups, <strong>and</strong> outside experts helped the community leaders focus on the problem<br />

Ind on a politically acceptable solution. Evaluation criteria were discovered, solutions generled,<br />

pros <strong>and</strong> cons discussed,-<strong>and</strong> eventually a successful decision was generated.<br />

PARTJ . THEORYAND PRACTICE CHAPTER2 . THE RATIONALPUBUC POUCy METHOD 49<br />

t<br />

I<br />

i<br />

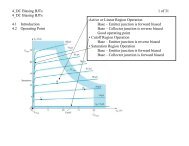

SMALL<br />

CHANGE<br />

FIGURE 2-2 DECISIONALTYPES<br />

PROBLEM DEFINITION<br />

(Agreement)<br />

Health<br />

Clinic<br />

Case<br />

PROBLEM DEFINITION<br />

(No Agreement)<br />

2<br />

4<br />

LARGE<br />

CHANGE<br />

The decision made in the Portersville case resulted in a policy in which problem definition<br />

was agreed upon <strong>and</strong> the policy change was small (the community already had a small<br />

clinic). The decision rested in quadrant I of the 2 X 2 matrix represented in Figure 2-2<br />

(adapted from Braybrooke <strong>and</strong> Lindblom 1970, 78).<br />

Some scholars suggest that it is only on the rare <strong>and</strong> relatively less-important issues<br />

like the Portersville Health Clinic, <strong>and</strong> unlike Vietnam, where the rational model makes<br />

sense. (Deciding what to do in Vietnam, especially with all the value conflict over problem<br />

definition, places it squarely in quadrant 4.) For example, Braybrooke <strong>and</strong> Lindblom<br />

(1970, pp. 78-79), referring to a rational model of policymaking as synoptic methods,<br />

write that "Synoptic methods. . . are limited to . . . those happy if limited circumstances<br />

in which decisions effect sufficiently small change to make synoptic underst<strong>and</strong>ing possible."<br />

They also quote Herbert Simon stating: "Rational choice will be feasible to the extent<br />

that the limited set of factors upon which decision is based corresponds, in nature, to a<br />

closed system of variables" (p. 39).<br />

In sum, the charge has been levied that the rational model is of little relevance or value<br />

to the policy analyst. Is this true? How does one evaluate models? An explanation of model<br />

evaluation follows.<br />

Model Evaluation<br />

The rational model, like almost all models, can best be judged by three criteria. The first<br />

criterion is the ability to accurately describe. The fancy word scholars use for this is<br />

verisimilitude. Verisimilitude translates to the two familiar words it sounds like-very similar.<br />

In other words, models are usually expected to describe accurately. A model of a B-52<br />

bomber should look enough like the real thing that you can identify it or at least distinguish<br />

it from the model of the space shuttle (even assuming you know no more about airplanes<br />

than the authors of this text).<br />

The second criterion is what has been called the ah-hah factor. That is, models should<br />

explain the world to us; they should help us make sense of what it is they purport to represent.