Voices of North American Owls - Macaulay Library

Voices of North American Owls - Macaulay Library

Voices of North American Owls - Macaulay Library

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

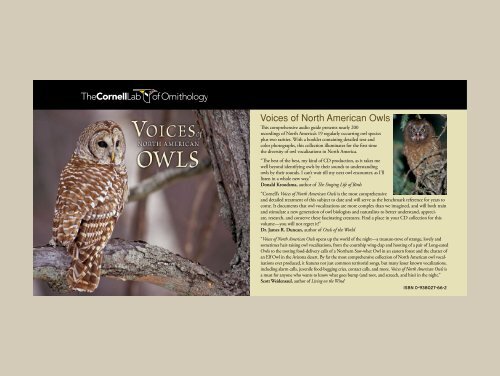

<strong>Voices</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>American</strong> <strong>Owls</strong><br />

This comprehensive audio guide presents nearly 200<br />

recordings <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> America’s 19 regularly occurring owl species<br />

plus two rarities. With a booklet containing detailed text and<br />

color photographs, this collection illuminates for the first time<br />

the diversity <strong>of</strong> owl vocalizations in <strong>North</strong> America.<br />

“The best <strong>of</strong> the best, my kind <strong>of</strong> CD production, as it takes me<br />

well beyond identifying owls by their sounds to understanding<br />

owls by their sounds. I can’t wait till my next owl encounter, as I’ll<br />

listen in a whole new way.”<br />

Donald Kroodsma, author <strong>of</strong> The Singing Life <strong>of</strong> Birds<br />

“Cornell’s <strong>Voices</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>American</strong> <strong>Owls</strong> is the most comprehensive<br />

and detailed treatment <strong>of</strong> this subject to date and will serve as the benchmark reference for years to<br />

come. It documents that owl vocalizations are more complex than we imagined, and will both train<br />

and stimulate a new generation <strong>of</strong> owl biologists and naturalists to better understand, appreciate,<br />

research, and conserve these fascinating creatures. Find a place in your CD collection for this<br />

volume—you will not regret it!”<br />

Dr. James R. Duncan, author <strong>of</strong> <strong>Owls</strong> <strong>of</strong> the World<br />

“<strong>Voices</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>American</strong> <strong>Owls</strong> opens up the world <strong>of</strong> the night—a treasure-trove <strong>of</strong> strange, lovely and<br />

sometimes hair-raising owl vocalizations, from the courtship wing-clap and hooting <strong>of</strong> a pair <strong>of</strong> Long-eared<br />

<strong>Owls</strong> to the tooting food-delivery calls <strong>of</strong> a <strong>North</strong>ern Saw-whet Owl in an eastern forest and the chatter <strong>of</strong><br />

an Elf Owl in the Arizona desert. By far the most comprehensive collection <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>American</strong> owl vocalizations<br />

ever produced, it features not just common territorial songs, but many lesser known vocalizations,<br />

including alarm calls, juvenile food-begging cries, contact calls, and more. <strong>Voices</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>American</strong> <strong>Owls</strong> is<br />

a must for anyone who wants to know what goes bump (and toot, and screech, and hiss) in the night.”<br />

Scott Weidensaul, author <strong>of</strong> Living on the Wind<br />

ISBN 0-938027-66-2

2<br />

“I rejoice that there are owls. Let them do the idiotic and maniacal hooting for men.<br />

It is a sound admirably suited to swamps and twilight woods which no day illustrates,<br />

suggesting a vast and undeveloped nature which men have not recognized. They represent<br />

the stark twilight and unsatisfied thoughts which all have.”<br />

Introduction<br />

<strong>Owls</strong> have persisted in man’s cultural<br />

consciousness since the beginning <strong>of</strong><br />

time. From the earliest cave paintings<br />

through modern times, owls have<br />

appeared in artifacts, myth, folklore, and<br />

legend. They represent a broad spectrum<br />

<strong>of</strong> meanings for different cultures and<br />

individuals around the world—regarded<br />

by some as symbols <strong>of</strong> wisdom and<br />

godliness, and by others as harbingers <strong>of</strong><br />

death. Few birds or other animals<br />

capture our minds and imaginations to<br />

the degree that owls do.<br />

Our emotional response to owls is <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

attributed to their human-like appearance.<br />

Their large forward-facing eyes and<br />

Henry David Thoreau, Walden<br />

expressive faces have contributed greatly<br />

to the lore surrounding them. Less <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

considered, but perhaps even more<br />

significant, are the sounds owls make.<br />

From the earliest hunter-gatherers sitting<br />

in darkness around a fire, to scientific researchers<br />

today, owl sounds in the night<br />

have presented a mystery to be feared or<br />

a question to be answered. Remarkably<br />

we still know little about owls and the<br />

meaning <strong>of</strong> their sounds. This compilation<br />

aims to shed new light on the<br />

intricacies <strong>of</strong> owl vocal behavior and to<br />

aid ornithologists and bird- watchers in<br />

detecting and identifying these denizens<br />

<strong>of</strong> the night. It is also hoped that the<br />

listener will gain a greater appreciation

for owls and the importance <strong>of</strong> conserving<br />

the habitats where they live.<br />

The Sounds <strong>Owls</strong> Make<br />

Primarily nocturnal, and <strong>of</strong>ten living in<br />

dark forested environments, owls rely<br />

heavily on sound both to find prey and<br />

to communicate. Most owls are built to<br />

receive sound, enabling them to locate<br />

prey aurally with great accuracy. They<br />

have also evolved rich repertoires <strong>of</strong><br />

vocalizations for communicating in the<br />

dark. These vocalizations are inherited<br />

and in many instances convey precise<br />

meanings to other owls. Upon hatching,<br />

young Barred <strong>Owls</strong> give specific<br />

calls that communicate hunger to their<br />

parents and stimulate the adults to feed<br />

them (Track 103). Though the character<br />

<strong>of</strong> this vocalization changes as young<br />

birds grow, it still carries its precise<br />

meaning; adult females use it to solicit<br />

food from their mates. (Track 100).<br />

3<br />

<strong>Owls</strong> use songs primarily for territorial<br />

proclamation, territorial defense, and<br />

mate attraction and bonding. Songs<br />

generally consist <strong>of</strong> multiple notes with<br />

intervals between notes usually less than<br />

twice the note duration. Typically they<br />

have high harmonics.<br />

Owl calls are used in a variety <strong>of</strong> other<br />

contexts such as begging, alarm, or aggression.<br />

Calls are generally single notes<br />

with longer intervals between notes.<br />

With a few exceptions, calls generally lack<br />

harmonics. Calls <strong>of</strong>ten vary significantly<br />

depending on an owl’s age, motivation, or<br />

stimuli. It is also common for a vocalization<br />

seemingly identical to a species’<br />

song, or a derivative <strong>of</strong> that vocalization,<br />

to be used as a call, such as hooting by<br />

male Long-eared and Snowy owls in nest<br />

defense.<br />

Although most owl species’ songs are<br />

unique, such as the low hooting <strong>of</strong> a<br />

Great Horned Owl or the whinny <strong>of</strong> an<br />

Eastern Screech-Owl, some calls appear<br />

to be used in similar contexts by many<br />

owl species. The discomfort call, <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

referred to as a “chitter” by researchers,<br />

is most <strong>of</strong>ten uttered by both adults and<br />

young when in close association with<br />

other owls or when being handled by<br />

researchers. This call commonly communicates<br />

discomfort, including hunger,<br />

but is also used during mutual preening<br />

(allopreening), food transfers, and<br />

copulation. Most owl species seem to<br />

produce analogous variations <strong>of</strong> this call<br />

under similar stimuli. Other similarities<br />

in calls <strong>of</strong> different species suggest other<br />

analogous call-types may exist. A system<br />

<strong>of</strong> naming and classifying these vocalizations<br />

is useful for standardizing the way<br />

that we talk about owl vocalizations.<br />

Some suggestions for alternate naming<br />

<strong>of</strong> vocalizations have been included in<br />

this production.<br />

About This Audio Guide<br />

Some selections on this guide were made<br />

strictly to illustrate particular vocalizations,<br />

some to illustrate behavioral<br />

sequences, and others for sheer listening<br />

pleasure. Therefore the length and quality<br />

<strong>of</strong> recordings within this production<br />

vary. Although every effort was made<br />

to include all known vocalizations for<br />

each species, many vocalizations remain<br />

unrecorded or unavailable. There are<br />

also vocalizations that have yet to be<br />

described or have only been described<br />

phonetically. This has made identification<br />

<strong>of</strong> many previously described calls<br />

and associated behavior problematic.<br />

Additionally, observing behavior associated<br />

with vocalizations <strong>of</strong> nocturnal<br />

animals is inherently difficult. Therefore<br />

the repertoire presented for each species<br />

should be considered incomplete and<br />

the accompanying text for each vocalization<br />

a conservative interpretation <strong>of</strong><br />

the available literature. Behavioral

contexts are described when known<br />

but should not be considered the only<br />

circumstances in which a species may<br />

use a particular vocalization. Though<br />

names given by researchers to some<br />

vocalizations can be misleading as to<br />

the function, we have tried to include<br />

the names by which many <strong>of</strong> the calls<br />

presented here are commonly known.<br />

For a more comprehensive written<br />

treatment <strong>of</strong> owl vocalizations, consult<br />

the additional references listed in this<br />

booklet. Track 1 contains a sample<br />

track <strong>of</strong> the guide.<br />

Playing Recordings In The Field<br />

The greatest care should be taken when<br />

using recordings <strong>of</strong> owls and other birds<br />

in the field. Playback <strong>of</strong> these recordings<br />

should be done responsibly, particularly<br />

during the breeding season when owls<br />

are most vocal. Some recordings on this<br />

guide, especially distress and alarm calls,<br />

could cause undue stress and should<br />

4<br />

never be played in the field. One <strong>of</strong> the<br />

most fulfilling ways to experience owls at<br />

night is simply to go out and listen.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

We extend our thanks and gratitude<br />

to those individuals and organizations<br />

that have helped us in the development<br />

<strong>of</strong> this audio guide. Tom Weber <strong>of</strong><br />

the Florida Museum <strong>of</strong> Natural History<br />

(FMNH), Jill Soha <strong>of</strong> the Borror<br />

Laboratory <strong>of</strong> Bioacoustics (BLB) at<br />

The Ohio State University, and Chantal<br />

Dussault <strong>of</strong> the Canadian Museum <strong>of</strong><br />

Nature (CMN), kindly searched their<br />

archives and provided unique recordings<br />

for this production. Thank you to<br />

Jack W. Bradbury and Sean O’Brien<br />

for reviewing the text in its entirety and<br />

providing valuable insights and additions.<br />

Our sincerest thanks also to those<br />

who provided their expertise, time, and<br />

knowledge in reviewing portions <strong>of</strong><br />

the species text and associated record-<br />

ings: Frederick R. Gehlbach, James R.<br />

Duncan, Robert W. Nero, Glenn A.<br />

Proudfoot, Denver W. Holt, Eric D.<br />

Forsman, D. Archibald McCallum,<br />

Bernard Lohr, Karla Kinstler, Richard<br />

J. Cannings, Gregory D. Hayward,<br />

Douglas E. Trapp, and Tony Angell.<br />

An additional thanks to Glenn A.<br />

Proudfoot and Bernard Lohr for their<br />

visits to the <strong>Macaulay</strong> <strong>Library</strong> during<br />

the development <strong>of</strong> this audio guide,<br />

and for archiving new field tapes for use<br />

in this production. Finally, our sincerest<br />

gratitude to the contributing recordists.<br />

Without their nocturnal forays, this<br />

guide would not have been possible.<br />

Contributing Recordists<br />

Arthur A. Allen, Harriette Barker, Charles<br />

M. Bogert, Kent Bovee, Meredith Bovee,<br />

Gregory F. Budney, Greg Clark, Richard<br />

J. Clark, Benjamin M. Clock, Kevin J.<br />

Colver, L. Irby Davis, Robert W.<br />

Dickerman, Lang Elliott, William R. Ev-<br />

ans, Steve Farbotnik, Robert C. Faucett,<br />

William R. Fish, J. R. Fletcher, Frederick<br />

R. Gehlbach, William W. H. Gunn,<br />

David S. Herr, Wilbur L. Hershberger,<br />

Virginia Huber, Albert Karvonen, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey<br />

A. Keller, Peter Paul Kellogg, Thomas<br />

Knight, Wendy Kuntz, Greg Lasley, J.<br />

David Ligon, Randolph S. Little, Bernard<br />

Lohr, Stewart D. MacDonald, Curtis A.<br />

Marantz, Joseph T. Marshall Jr., Brian<br />

J. McCaffery, D. Archibald McCallum,<br />

Hugh P. McIsaac, Matthew D. Medler,<br />

Rosa Meehan, Martin C. Michener, Sean<br />

O’Brien, Sture Palmer, Leonard J. Peyton,<br />

Tim Price, Glenn A. Proudfoot, George<br />

B. Reynard, Jeffrey Rice, Robert Righter,<br />

Andres M. Sada, Thomas G. Sander, David<br />

T. Spaulding, Sally Sp<strong>of</strong>ford, Robert<br />

C. Stein, Charles A. Sutherland, Gerrit<br />

Vyn, Scott Weidensaul, and Steven G.<br />

Wilson.

Resources And Bibliography<br />

The Birds <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> America Online<br />

www.bna.birds.cornell.edu<br />

Johnsgard, P. A. <strong>North</strong> <strong>American</strong> <strong>Owls</strong>:<br />

Biology and Natural History, 2nd edition.<br />

Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution;<br />

2002.<br />

Duncan, J. R. <strong>Owls</strong> <strong>of</strong> the World: Their<br />

Lives, Behavior, and Survival. Buffalo,<br />

NY: Firefly Books; 2003.<br />

König, C., F. Weick, and J. Becking.<br />

<strong>Owls</strong>: A Guide to <strong>Owls</strong> <strong>of</strong> the World. New<br />

Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1999.<br />

Owl Research Institute, an organization<br />

dedicated to owl research,<br />

conservation, and public education<br />

www.owlinstitute.org<br />

5<br />

The Owl Foundation, a center for the<br />

rehabilitation <strong>of</strong> Canadian owl species<br />

and the behavioral observation <strong>of</strong><br />

permanently damaged wild owls in a<br />

breeding environment<br />

www.theowlfoundation.ca<br />

A Note To Recordists<br />

And Researchers<br />

This guide represents a first step in<br />

classifying and disseminating the songs<br />

and calls <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>American</strong> owls.<br />

Researchers and recordists are invited<br />

to contribute their recordings for future<br />

editions <strong>of</strong> this guide and to provide<br />

any written insights into the material<br />

presented here. We hope that this collection<br />

will serve as a working reference<br />

for those describing and studying owl<br />

vocalizations and behavior.<br />

For production purposes, changes to<br />

inter-song interval and other edits<br />

have been made to some recordings.<br />

For research purposes, please visit our<br />

website to obtain source recordings. Our<br />

complete audio catalogue is available for<br />

listening and spectrographic anaysis at<br />

www.macaulaylibrary.org.<br />

The preservation and study <strong>of</strong> acoustic<br />

communication recordings <strong>of</strong> birds and<br />

other animals is the focus <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Macaulay</strong><br />

<strong>Library</strong> at the Cornell Lab <strong>of</strong> Ornithology.<br />

To learn more about how wildlife recordings<br />

are made, how to participate in this work,<br />

and how to become a member <strong>of</strong> the Cornell<br />

Lab <strong>of</strong> Ornithology, please contact us.<br />

<strong>Macaulay</strong> <strong>Library</strong><br />

Cornell Lab <strong>of</strong> Ornithology<br />

159 Sapsucker Woods Road<br />

Ithaca, NY 14850<br />

telephone: (607) 254-2404<br />

email: macaulaylibrary@cornell.edu<br />

website: www.macaulaylibrary.org<br />

Interpreting and conserving the earth’s<br />

biological diversity through research, education,<br />

and citizen science focused on birds

VOICES OF NORTH AMERICAN OWLS TRACK LIST<br />

Barn Owl Tyto alba<br />

The Barn Owl’s screams, pale ghostlike appearance,<br />

and inhabitation <strong>of</strong> abandoned<br />

buildings, farms, and church belfries have<br />

probably contributed to superstitions about<br />

owls around the world. Barn <strong>Owls</strong> are vocally<br />

active when breeding and use a wide<br />

repertoire <strong>of</strong> acoustic signals. Most <strong>of</strong> their<br />

vocalizations fall into the category <strong>of</strong> hisses<br />

and screams, with different calls <strong>of</strong>ten grading<br />

into each other. This makes it difficult to<br />

distinguish between subtly different calls, describe<br />

them phonetically, and associate them<br />

with a specific behavior. Female screams are<br />

generally huskier and less consistently given<br />

than male screams, but sexing individuals<br />

based on this is generally not definitive.<br />

Track Number/Description<br />

2. Territorial scream or advertising call.<br />

A male probably produced this call, described<br />

as karr-r-r-r-r-ick. (California, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey A.<br />

Keller, ML 50147)<br />

3. Territorial scream or advertising call.<br />

Described as shrrreeeeee, this call was probably<br />

made by a female. (Washington, David S.<br />

Herr, ML 50540)<br />

4. Territorial screams and wing-clap display.<br />

The first scream is probably by a male, the<br />

second by a female. (New York, Charles A.<br />

Sutherland, ML 8323)<br />

6<br />

5. Warning scream, or alarm call <strong>of</strong> an adult.<br />

(Washington, David S. Herr, ML 50541)<br />

6. Distress call <strong>of</strong> a captive owl. This call<br />

indicates intense distress or fear such as when<br />

an owl has been seized or is in an intense<br />

fight. (New York, Martin C. Michener, ML<br />

8320)<br />

7. Sustained defensive hiss, bill-clap, and<br />

warning scream by captive advanced nestlings.<br />

(New York, Sally Sp<strong>of</strong>ford, ML 8325)<br />

8. Sustained defensive hiss by an adult. <strong>Owls</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong>ten use this call when threatened or cornered,<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten accompanied by threat postures.<br />

If the danger persists, this call <strong>of</strong>ten grades<br />

into the distress call. These calls and the related<br />

postures are intended to intimidate predators.<br />

Captive. (New York, Peter Paul Kellogg,<br />

ML 8319)<br />

9. Kleak-kleak call. The male commonly utters<br />

this call in flight during nesting, <strong>of</strong>ten to<br />

announce food deliveries to the nest.<br />

(California, Robert C. Stein, ML 8322)<br />

10. Calls recorded at a nest. The behavioral<br />

context for this recording is unknown but<br />

calls suggesting the food-<strong>of</strong>fering call and<br />

adult begging snore are heard in this recording.<br />

A male may have been delivering food to<br />

an incubating female. (California, William R.<br />

Fish, ML 22812)<br />

11. Fledgling mobbing call.<br />

<strong>Owls</strong> usually direct this scolding<br />

call toward terrestrial predators,<br />

including humans. A<br />

second fledgling is audible, uttering<br />

begging snores. (Florida,<br />

Gerrit Vyn, ML 104569)<br />

12. Fledgling begging snore.<br />

Juvenile and female owls<br />

use this self-advertising call.<br />

The calls’ intensity increases<br />

with hunger and the arrival<br />

<strong>of</strong> adults with food. Hungry<br />

fledglings will give this call<br />

persistently throughout the<br />

night. (Florida, Gerrit Vyn,<br />

ML 104569)<br />

Juan Bahamon

Flammulated Owl Otus flammeolus<br />

Although the Flammulated Owl is one or our<br />

smallest owls, its hoot is one <strong>of</strong> the lowestfrequency<br />

owl songs in <strong>North</strong> America. The<br />

male’s hoot also has a ventriloquial quality,<br />

making it difficult to observe this small, cryptically<br />

colored, nocturnal owl. The owls also<br />

vary the amplitude <strong>of</strong> their hoots, making it<br />

difficult to judge the distance to a calling owl.<br />

The vocalizations <strong>of</strong> adult Flammulated <strong>Owls</strong><br />

consist <strong>of</strong> one basic note type which grades<br />

from short hoots to long shrieks, with many<br />

variations in between. These varied intermediate<br />

calls are commonly described as barks<br />

and moans.<br />

13. Male territorial hoot or advertising song.<br />

Males primarily give the single-note hoot<br />

when singing. When a male is agitated, such<br />

as when another male invades a territory,<br />

the hoot may be accompanied by additional<br />

notes, or may become more quiet, hoarse,<br />

and with multiple notes, as is heard in the<br />

last call here. (Oregon, David S. Herr, ML<br />

47540)<br />

14. Female hoot. A female uttered these<br />

hoots as she solicited courtship feedings<br />

from a male. (New Mexico, D. Archibald<br />

McCallum, 5/12/81)<br />

7<br />

15. Begging snores <strong>of</strong> nestlings and low amplitude<br />

hoot given by an adult announcing<br />

a food delivery to the nest. Adults also use<br />

low amplitude hoots as a contact call between<br />

mates. (Oregon, David S. Herr, ML 50536)<br />

16. Bark by an alarmed female, and nestling<br />

begging snore. Barking can escalate into a variety<br />

<strong>of</strong> screams and shrieks depending on an<br />

owl’s level <strong>of</strong> agitation or aggression. (Oregon,<br />

David S. Herr, ML 50536)<br />

17. Male bark in response to a human<br />

intruder near a pair. (New Mexico, D.<br />

Archibald McCallum, 4/29/03)<br />

18. Female moan. (New Mexico, D.<br />

Archibald McCallum, 7/6/83)<br />

19. Distress shriek and bill-clap <strong>of</strong> an injured<br />

bird. (Texas, Greg Lasley, FMNH 1288)<br />

Brian E. Small

Western Screech-Owl Megascops kennicotti<br />

Like other <strong>North</strong> <strong>American</strong> screech-owls, the<br />

Western Screech-Owl uses two song types.<br />

The bouncing ball song is used for territorial<br />

advertisement and defense. The double trill is<br />

a mate coordination song and is heard more<br />

frequently in pair duetting. Males sing most<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten in winter and early spring prior to egglaying.<br />

They <strong>of</strong>ten sing from potential nest<br />

cavities or nest trees. Singing increases again<br />

in late summer as young disperse from adult<br />

territories. Both sexes share the adult vocalizations,<br />

with the female having a noticeably<br />

higher voice.<br />

20. Pair duet. Bouncing ball and double trill<br />

songs are given by both sexes. The female’s<br />

voice is higher pitched. Various unidentified<br />

calls are audible during an interaction<br />

between a pair at the end <strong>of</strong> the recording. Elf<br />

Owl (Micrathene whitneyi) barks are also audible<br />

during the duet. (Arizona, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey A.<br />

Keller, ML 109017)<br />

21. Double trill song followed by bouncing<br />

ball song. Mates use the double trill as<br />

a contact call. The male also uses the double<br />

trill to announce food deliveries to the nest.<br />

(Washington, David S. Herr, ML 47692)<br />

22. Agitated bark and bill-clap. (Washington,<br />

David S. Herr, ML 63001)<br />

8<br />

23. Te-te-do call progressing into agitated<br />

double trill. This call requires further study<br />

but is known to be given by owls when confronted<br />

by others <strong>of</strong> the same species. It may<br />

be an intense proclamation <strong>of</strong> territory and<br />

is <strong>of</strong>ten combined with the double trill. It is<br />

also similar to the solicitation or begging call<br />

<strong>of</strong> females and juveniles. (Oregon, David S.<br />

Herr, ML 50549)<br />

24. Female solicitation call or begging whinny.<br />

The female uses this call to solicit feedings<br />

and copulation in the early stages <strong>of</strong> nesting<br />

and when incubating and brooding young.<br />

It is derived from the juvenile begging call.<br />

(Alaska, Kent and Meredith Bovee, 4/29/05)<br />

Robert McMorran

Eastern Screech-Owl Megascops asio<br />

The Eastern Screech-Owl uses its descending<br />

trill song, or whinny, mainly for territorial<br />

advertisement or defense. Adults most<br />

commonly use this song from the time when<br />

fledglings disperse in late summer until<br />

courtship begins again in mid-winter. The<br />

monotonic trill song establishes pair and family<br />

bonds and is primarily used during the<br />

courtship and pre-nesting period from midwinter<br />

through spring. The owls also produce<br />

variations <strong>of</strong> this song during copulation and<br />

nest-cavity advertising. Additionally, the male<br />

uses the song prior to food deliveries and the<br />

female uses it to induce fledging. Pair duets<br />

are common and neighboring males will also<br />

synchronize their singing. Considerable variation<br />

in both song types between individuals<br />

may serve in sexual and individual recognition.<br />

Both sexes utter all vocalizations, with<br />

the male’s voice noticeably lower.<br />

25. Descending trill or whinny, followed by<br />

the monotonic trill. The monotonic trill is<br />

a variable vocalization that sometimes has a<br />

bouncing quality as is heard in this example.<br />

At other times it is a more consistently delivered<br />

song. Captive. (New York, Hugh P.<br />

McIsaac, ML 20427)<br />

9<br />

26. Descending trill during territorial defense.<br />

(Maryland, Wilbur L. Hershberger,<br />

ML 100704)<br />

27. Monotonic trill with descending trill<br />

in the background. (Maryland, Wilbur L.<br />

Hershberger, ML 107446)<br />

28. Monotonic trill with evenly spaced notes.<br />

Chuck-will’s-widow (Caprimulgus carolinensis)<br />

is prominently audible in the background.<br />

(Florida, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey A. Keller, ML 105733)<br />

29. Monotonic trill <strong>of</strong> shorter duration<br />

by M.a. mccallii in South Texas. (Texas,<br />

Matthew D. Medler, ML 87462)<br />

30. Screech calls and bill-claps by agitated<br />

pair. (Maryland, Wilbur L. Hershberger, ML<br />

94524)<br />

31. Screech and chuckle rattle. Both nestlings<br />

and adults utter the chuckle rattle, generally<br />

signifying annoyance. Captive. (New York,<br />

Hugh P. McIsaac, ML 20428)<br />

32. Bark call. Captive. (New York, Hugh P.<br />

McIsaac, ML 20428)<br />

33. Begging rasps, chitter calls, and chuckle<br />

rattle <strong>of</strong> nestlings. (New York, Arthur A.<br />

Allen, ML 4451, 4452, 4451, 39893)<br />

34. Food delivery at a nest. (New York,<br />

Arthur A. Allen, ML 39890)<br />

Gerrit Vyn

Whiskered Screech-Owl Otus trichopsis<br />

The Whiskered Screech-Owl uses its short<br />

trill as a song for territorial proclamation<br />

and defense, as well as for pair bonding and<br />

contact. The telegraphic trill is a variable syncopated<br />

song <strong>of</strong>ten sung in duet by pairs. It<br />

is associated with pair contact, defense <strong>of</strong> territory,<br />

and copulation. Both sexes sing, with<br />

the female having a noticeably higher voice.<br />

Most singing occurs at night with peaks in<br />

singing at dusk and before sunrise. Like Elf<br />

<strong>Owls</strong> and other screech-owls, Whiskered<br />

Screech-<strong>Owls</strong> sing most frequently during<br />

gibbous to full moons on clear nights.<br />

35. Male short trill. The male uses this song<br />

in territorial defense and when advertising<br />

prospective nest cavities. (New Mexico,<br />

Curtis A. Marantz, ML 112621)<br />

36. Male short trill. (Arizona, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey A.<br />

Keller, ML 40588)<br />

37. Telegraphic trill <strong>of</strong> male. (Arizona, Greg<br />

Clark, 1/97)<br />

38. Telegraphic trill by a pair followed by a<br />

squeal during an encounter with an invading<br />

owl. Pairs also use this song in response to<br />

small singing owls <strong>of</strong> other species. (Arizona,<br />

Bernard Lohr, 5/31/99)<br />

10<br />

39. Male prolonged or long trill. This song<br />

is only known to be given by the male in the<br />

immediate vicinity <strong>of</strong> the nest cavity. It may<br />

signal intense territoriality. When a female<br />

is present, the call may become deeper and<br />

more guttural (not heard here). (Arizona,<br />

Bernard Lohr, 5/30/99)<br />

40. Hoot. This call may be a warning in response<br />

to the presence <strong>of</strong> potential predators.<br />

(Arizona, Greg Clark and Tim Price, 1/97)<br />

41. Male whistle call. Used by both sexes in<br />

mate contact, this call <strong>of</strong>ten precedes copulation.<br />

(Arizona, Frederick R. Gehlbach,<br />

6/21/98)<br />

42. Bark series. This was one <strong>of</strong> three series <strong>of</strong><br />

bark-like calls by a male near a nest. (Arizona,<br />

Bernard Lohr, 5/30/99)<br />

43. Female bark call transitioning into<br />

screech. <strong>Owls</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten direct barks at intruders<br />

near the nest. The barks may escalate<br />

into screeches as an owl’s level <strong>of</strong> agitation<br />

or aggression increases. (Arizona, Joseph T.<br />

Marshall Jr., ML 4506)<br />

44. Copulation sequence. The female whistle–calls<br />

prior to copulation, followed by the<br />

telegraphic trill from both sexes. Both sexes<br />

utter other calls during copulation. (Arizona,<br />

Frederick R. Gehlbach)<br />

Brian E. Small

Great Horned Owl Bubo virginianus<br />

Although the Great Horned Owl is our most<br />

widespread and recognized owl species, its<br />

wide repertoire <strong>of</strong> calls is little known and<br />

poorly understood. In addition to the familiar<br />

territorial hooting, Great Horned <strong>Owls</strong> utter<br />

a variety <strong>of</strong> barks, growls, screams, and chuckles<br />

that are difficult to characterize. Pair duets<br />

can be heard throughout <strong>North</strong> America at<br />

any time <strong>of</strong> the year but most frequently in<br />

late winter and early spring prior to egg laying.<br />

Males can always be distinguished from<br />

females by their deeper, more mellow voice.<br />

Considerable variation exists in the timing<br />

and number <strong>of</strong> hoots in a song. The fledgling<br />

begging call is another commonly heard<br />

call in the field that observers <strong>of</strong>ten do not<br />

recognize. It can be heard from late spring<br />

through fall.<br />

45. Territorial hooting or advertisement<br />

song. Often sung in duet, this call announces<br />

a territory and may serve to strengthen the<br />

pair bond. It is heard most commonly prior<br />

to egg-laying, <strong>of</strong>ten in the immediate vicinity<br />

<strong>of</strong> a chosen nest. When giving this hoot in<br />

song, the owl assumes a forward leaning posture<br />

with a cocked tail and an inflated throat.<br />

The number and timing <strong>of</strong> hoots varies<br />

among different individuals and populations.<br />

A double-hoot by the female is also audible.<br />

11<br />

This is probably the result <strong>of</strong> an interruption,<br />

rather than being a unique vocalization.<br />

(California, William R. Fish, ML 22874)<br />

46. Territorial hooting duet followed by<br />

copulation calls. Both birds, particularly the<br />

male, can be heard giving repeated hoots during<br />

copulation, followed by a squealing chitter<br />

call by the female. The interaction ends<br />

with a resumption <strong>of</strong> the duet. (New York,<br />

Gerrit Vyn, ML 128900)<br />

47. Female squawk with male territorial<br />

hoot in the distance. The squawk is a variable<br />

call sometimes used as a food solicitation call<br />

by the female early in the breeding season.<br />

The male also uses it. It is probably derived<br />

from the juvenile begging call. (Connecticut,<br />

Sean O’Brien)<br />

48. Female chitter call and squawk and male<br />

territorial hooting. (Maryland, Wilbur L.<br />

Hershberger, ML 94364)<br />

49. Male territorial hooting, female territorial<br />

hooting and squawks. (Arizona, Charles<br />

M. Bogert, ML 8366)<br />

50. Bark-like call. This may be a single wac<br />

call as heard on the following track. Captive.<br />

(Pennsylvania, Peter Paul Kellogg, ML 8359)<br />

51. Wac-wac call and billclap<br />

by a female during nest<br />

defense. Male hooting, which<br />

may functionally be a nestdefense<br />

or alarm call in this<br />

context, is audible in the background.<br />

(Manitoba, William<br />

W. H. Gunn, ML 59821)<br />

52. Squealing chitter call <strong>of</strong><br />

an injured bird. This call varies<br />

in intensity and generally expresses<br />

discomfort or agitation.<br />

Adults and juveniles use it in a<br />

variety <strong>of</strong> contexts. (New York,<br />

Peter Paul Kellogg, ML 8360)<br />

53. Fledgling begging<br />

call. (New York, David T.<br />

Spaulding, ML 8380)<br />

Gerrit Vyn

Snowy Owl Bubo scandiaca<br />

During the breeding season, Snowy <strong>Owls</strong><br />

are vocally active and use a wide repertoire <strong>of</strong><br />

vocalizations. This is especially true <strong>of</strong> males,<br />

who are more responsible for the defense <strong>of</strong><br />

territory and nest than are females. Little information<br />

is available on the vocal activity <strong>of</strong> this<br />

species outside <strong>of</strong> the nesting season, though it<br />

is clear they call infrequently. They are known<br />

to give several calls on their wintering grounds,<br />

particularly when defending winter feeding<br />

territories from other Snowy <strong>Owls</strong>. One call,<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten described as a scream, is probably a variation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the mewing whistle. It is given by both<br />

sexes and <strong>of</strong>ten by owls that are approached<br />

too closely by observers.<br />

54. Male territorial hoot or advertising song.<br />

Usually uttered in twos, variations <strong>of</strong> this<br />

vocalization probably serve as both song and<br />

call at times. When advertising a territory,<br />

males assume a forward bowing posture<br />

when giving this call. They also occasionally<br />

utter it in flight. Hooting volume is loudest<br />

during territorial defense. Females are known<br />

to hoot but rarely do so. (Sweden, Sture<br />

Palmer, ML 9435)<br />

55. Female bark call and bill snap. This alarm<br />

call is the most common call heard by human<br />

intruders at the nest. The piping squeals <strong>of</strong><br />

small chicks are also audible in this recording.<br />

12<br />

(Nunavut, Canada, Stewart D. MacDonald,<br />

CMN)<br />

56. Male bark call given in alarm at a nest.<br />

The begging squeals <strong>of</strong> chicks are also audible.<br />

(Nunavut, Canada, Stewart D. MacDonald,<br />

CMN)<br />

57. Mewing whistle <strong>of</strong> female. Primarily given<br />

by the female, this call is used in a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

situations, most commonly when soliciting<br />

food from the male at the nest. She also uses<br />

this call before and after being fed by the male,<br />

during distraction display, and in displacement<br />

coition. This call is also given in alarm when<br />

humans are near a nest. (Nunavut, Canada,<br />

Stewart D. MacDonald, CMN)<br />

58. Unidentified call. (Sweden, Sture Palmer,<br />

ML 9435)<br />

59. Unidentified call. (Sweden, Sture Palmer,<br />

ML 9434)<br />

60. Begging squeal and chitter call <strong>of</strong> fiveday-old<br />

chick. (Nunavut, Canada, Stewart D.<br />

MacDonald, CMN)<br />

61. Fledgling begging call and chitter. Young<br />

Snowy <strong>Owls</strong> leave the nest at an early age and<br />

disperse across the tundra around the nest. This<br />

call serves as a begging call and self-advertisement<br />

so adults can locate them for feeding.<br />

(Sweden, Sture Palmer, ML 9435)<br />

Gerrit Vyn

Spotted Owl (“<strong>North</strong>ern” subspecies) Strix occidentalis caurina<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> its status as an endangered species,<br />

the Spotted Owl has been studied more than<br />

any other <strong>North</strong> <strong>American</strong> owl. Vocally active,<br />

it commonly calls during the day if provoked to<br />

defend its territory. Otherwise, it is most vocal<br />

after sunset, early evening, and dawn. The sexes<br />

can usually be distinguished by voice pitch; the<br />

female’s vocalizations are higher. Both sexes use<br />

most vocalizations, but some <strong>of</strong> them are used<br />

more regularly by one sex. Most Spotted Owl<br />

hooting and contact vocalizations are used and<br />

intermixed during territorial encounters. These<br />

calls can vary significantly depending on the<br />

individual and circumstances. Playing recordings<br />

in the field <strong>of</strong> this federally protected endangered<br />

species is strongly discouraged.<br />

62. Male advertisement hooting or four-note<br />

location call. This is the most common hooting<br />

call. The male uses this primary song to<br />

announce a territory or when engaging in territorial<br />

disputes. Members <strong>of</strong> a pair also use it<br />

as a location call. A female contact whistle is<br />

audible in the background. (Oregon, Thomas<br />

G. Sander, ML 125367)<br />

63. Female advertisement hooting or fournote<br />

location call. (Oregon, Thomas G.<br />

Sander, ML 125377)<br />

64. Variation <strong>of</strong> four-note location call by a<br />

female. <strong>Owls</strong> commonly produce a three-note<br />

13<br />

location call when agitated. (Oregon, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey<br />

A. Keller, ML 56948)<br />

65. Variation <strong>of</strong> four-note location call by<br />

a male. In this example, the owl adds a note<br />

to the end <strong>of</strong> the call. (Oregon, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey A.<br />

Keller, ML 56949)<br />

66. Male series location call with female<br />

contact whistle in the background. This variable<br />

call consists <strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> hoots <strong>of</strong>ten ending<br />

with hoots similar to those ending the fournote<br />

location call. Males commonly use this<br />

call in territorial disputes but pairs also use it<br />

as a contact call. (Oregon, Thomas G. Sander,<br />

ML 125369)<br />

67. Female series location call consisting<br />

<strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> evenly spaced notes. (Oregon,<br />

Thomas G. Sander, ML 125377)<br />

68. Female series location call ending with an<br />

agitated contact whistle. (Oregon, Thomas G.<br />

Sander, ML 125375)<br />

69. Male series location call followed by female<br />

contact whistle. (Oregon, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey A.<br />

Keller, ML 56948)<br />

70. Contact whistle. This call is commonly<br />

heard and can vary greatly in intensity. Used<br />

more <strong>of</strong>ten by the female, this call advertises<br />

her location to her mate and <strong>of</strong>fspring.<br />

(Oregon, Thomas G. Sander, ML 125361)<br />

71. Female agitated contact whistle <strong>of</strong> varying<br />

intensities. (Oregon, Thomas G. Sander, ML<br />

125374)<br />

72. Female bark series. This variable call is primarily<br />

used by the female during high intensity<br />

territorial disputes. It is also used as a general contact<br />

call in some instances. (Oregon, Thomas G.<br />

Sander, ML 125373)<br />

73. Mellow female contact whistle and male nest<br />

call. The male uses the nest call when advertising<br />

potential nest sites to the female in the pre-nesting<br />

period, <strong>of</strong>ten calling continuously for several minutes.<br />

(California, Arthur A. Allen, ML 4544)<br />

74. Interaction between mates. A male utters a<br />

contact whistle in flight as he approaches a female,<br />

possibly delivering food. The female responds with<br />

a chitter call, followed by an agitated location call<br />

while the male begins giving the typical four-note<br />

location call. The female continues with whistle<br />

contact calls. The agitated location call is similar<br />

to the four-note location call but ends with an<br />

excited OW!. It is frequently heard when birds are<br />

excited during territorial encounters, sexual encounters,<br />

or food exchanges. (Oregon, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey A.<br />

Keller, ML 56948)<br />

75. Interaction by members <strong>of</strong> a pair. The male<br />

utters the series location call as the female flies<br />

in, giving contact whistles and chitter calls as she<br />

arrives. She then gives typical four-note location<br />

calls as the male departs, issuing agitated<br />

location calls. The female may have been<br />

soliciting a food transfer from the male.<br />

The chitter call is used during food transfers,<br />

copulation, and allopreening. It is also<br />

known to be used to express discomfort.<br />

(Oregon, Thomas G. Sander, ML 125368)<br />

Gerrit Vyn

Spotted Owl (“Mexican” subspecies) Strix occidentalis lucida<br />

The vocal behavior <strong>of</strong> the “Mexican”<br />

Spotted Owl is generally the same as that<br />

<strong>of</strong> the “<strong>North</strong>ern” Spotted Owl, though the<br />

Mexican subspecies is less inclined to vocalize<br />

during the day. Further descriptions and<br />

behavioral contexts <strong>of</strong> these calls can be found<br />

in the previous section about the northern<br />

subspecies. Playing recordings in the field <strong>of</strong><br />

this federally protected endangered species is<br />

strongly discouraged.<br />

76. Male advertisement hooting or four-note<br />

location call. (New Mexico, Wendy Kuntz,<br />

3/14/95)<br />

77. Male advertisement hooting or four-note<br />

location call. (New Mexico, Wendy Kuntz,<br />

6/19/96)<br />

78. Female advertisement hooting or fournote<br />

location call. A male is also audible in<br />

the background. (Arizona, Virginia Huber,<br />

ML 20869)<br />

79. Female agitated location call, male<br />

four-note location call, and female agitated<br />

contact whistle. The agitated location call is<br />

similar to the four-note but ends in an excited<br />

OW!. (Arizona, Virginia Huber, ML 20869)<br />

80. Female and male agitated location calls.<br />

In this example, the higher-pitched female<br />

14<br />

has omitted the first note. (New Mexico,<br />

Wendy Kuntz, 6/10/96)<br />

81. Male series location call with unevenly<br />

spaced notes. (New Mexico, Wendy Kuntz,<br />

7/16/96)<br />

82. Male series location call with evenly<br />

spaced notes. (New Mexico, Wendy Kuntz,<br />

4/5/96)<br />

83. Whistle contact calls <strong>of</strong> variable intensity<br />

by male and female. (New Mexico, Wendy<br />

Kuntz, 6/10/96)<br />

84. Agitated contact whistles by a pair. (New<br />

Mexico, Wendy Kuntz, 6/10/96)<br />

85. Bark series by male and female. The<br />

song <strong>of</strong> Canyon Wren (Catherpes mexicanus)<br />

is audible in the background. (New Mexico,<br />

Wendy Kuntz, 8/3/96)<br />

86. Various cooing calls between pair.<br />

Cooing calls are variable s<strong>of</strong>t calls <strong>of</strong>ten used<br />

when members <strong>of</strong> a pair are in close association,<br />

such as when roosting together or<br />

allopreening. (New Mexico, Wendy Kuntz,<br />

8/1/96)<br />

87. Variable contact-like calls and barks.<br />

(Arizona, Virginia Huber, ML 20870)<br />

88. Copulation sequence. (Arizona, Virginia<br />

Huber, ML 20869)<br />

89. Male prey delivery to female. Male gives<br />

four-note location call and agitated location<br />

call; female responds with chitter, squeals,<br />

and contact-like calls. (New Mexico, Wendy<br />

Kuntz, 5/7/96)<br />

90. Fledgling begging call. This call gradually<br />

develops into the adult contact call. (New<br />

Mexico, Wendy Kuntz, 6/23/96)<br />

Spotted Owl x Barred Owl hybrid<br />

Strix occidentalis x varia<br />

Unsustainable forestry practices in the Pacific<br />

<strong>North</strong>west have not only eliminated most <strong>of</strong><br />

the Spotted Owl’s old-growth forest habitat,<br />

but they have created corridors <strong>of</strong> younger<br />

forest habitat that the more adaptable Barred<br />

Owl has readily occupied. The fragmentation<br />

<strong>of</strong> Spotted Owl habitat and subsequent invasion<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Barred Owl into adjacent territory<br />

has put the Spotted Owl at great risk <strong>of</strong> being<br />

displaced by the more aggressive and closely<br />

related Barred Owl or <strong>of</strong> breeding with it. In<br />

many cases the two species have hybridized,<br />

producing viable <strong>of</strong>fspring, which further<br />

threaten the survival <strong>of</strong> the Spotted Owl, an<br />

endangered species.<br />

91. Advertisement hooting. (Washington,<br />

J. R. Fletcher, ML 93740)

Barred Owl Strix varia<br />

The Barred Owl is one <strong>of</strong> the most spectacular<br />

vocal performers <strong>of</strong> any <strong>North</strong> <strong>American</strong><br />

bird. Its familiar who cooks for you, who cooks<br />

for you all territorial announcement song, or<br />

two-phrase hoot, can be heard in many parts<br />

<strong>of</strong> the continent. Female calls can usually be<br />

distinguished from those <strong>of</strong> males by their<br />

higher pitch and more tremulous trailing<br />

notes. Pairs defending or announcing a territory<br />

frequently caterwaul, producing a variety<br />

<strong>of</strong> spectacular hoots, squeals, and quacks.<br />

These caterwauling bouts are strictly performed<br />

by mated pairs, usually to announce<br />

or defend a territory against other Barred<br />

<strong>Owls</strong>. The ascending hoot is another territorial<br />

hooting variation commonly heard when<br />

one pair confronts another. Barred <strong>Owls</strong><br />

are one <strong>of</strong> the few owl species that are commonly<br />

heard throughout the day in many<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> their range, particularly in southern<br />

swamplands where breeding densities are the<br />

highest.<br />

92. Female two-phrase hoot, ascending hoot,<br />

and pair caterwauling. (South Carolina,<br />

Ge<strong>of</strong>frey A. Keller, ML 105433)<br />

93. Pair caterwauling. (Florida, William R.<br />

Evans, ML 49708)<br />

94. Pair caterwauling with nestling begging<br />

15<br />

call in background. (Arkansas, Gerrit Vyn<br />

and Benjamin M. Clock, ML 128923)<br />

95. Female two-phrase hoot, followed by<br />

male ascending hoot, and a female ascending<br />

hoot variation. This variation is similar<br />

to that heard being given by an owl in flight<br />

on Track 100. (Arkansas, Gerrit Vyn and<br />

Benjamin M. Clock, ML 128930)<br />

96. Territorial dispute between two pairs. The<br />

proximate pair gives ascending hoots. Female<br />

two-phrase hoots and caterwauling are audible<br />

from a neighboring pair. (Arkansas, Gerrit Vyn<br />

and Benjamin M. Clock, ML 128925)<br />

97. Territorial dispute between two pairs.<br />

Ascending hoots, caterwauling, and a booming<br />

hoo-aw call are audible. (Arkansas, Gerrit<br />

Vyn and Benjamin Clock, ML 128926)<br />

98. Male hoo-aw call. This call may be used<br />

as a long distance contact call between mates.<br />

(Arkansas, Gerrit Vyn, ML 128927)<br />

99. Female hoo-aw call. Mates may use this<br />

call as a long distance contact call. (New York,<br />

Randolph S. Little, ML 106944)<br />

100. Female hoot variation. Females have<br />

been observed giving this call in flight while<br />

chasing other Barred <strong>Owls</strong> invading their territory.<br />

(Arkansas, Gerrit Vyn, ML 128931)<br />

101. Female solicitation call<br />

from nest cavity. When incubating<br />

eggs or brooding young<br />

chicks, females may utter this<br />

call repeatedly throughout the<br />

night as a food begging call<br />

to their mates. This call is also<br />

used as a contact call in some<br />

circumstances. (Arkansas,<br />

Gerrit Vyn, ML 128902)<br />

102. Distraction squeals and<br />

honk by a female in response to<br />

a large predator near the nest.<br />

This call is possibly being used in<br />

an injury-feigning display.<br />

(Arkansas, Gerrit Vyn and<br />

Benjamin M. Clock, ML<br />

128924)<br />

103. Fledgling begging call.<br />

(Florida, Robert C. Stein, ML<br />

4549)<br />

104. Fledgling begging call and<br />

male two-phrase hoot.<br />

(Maryland, Wilbur L.<br />

Hershberger, ML 79462)<br />

Gerrit Vyn

Great Gray Owl Strix nebulosa<br />

The Great Gray Owl has a large vocal repertoire<br />

during the breeding season. Both sexes use<br />

many <strong>of</strong> the same calls. Calls associated with<br />

defense <strong>of</strong> the nest and contact between pairs<br />

and juveniles are especially diverse and variable.<br />

Territorial hooting is most <strong>of</strong>ten heard during<br />

late winter and spring, but is also heard at<br />

other times <strong>of</strong> the year. The juvenile begging<br />

call is also frequently heard. It <strong>of</strong>ten sounds<br />

similar to that <strong>of</strong> the Great Horned Owl.<br />

105. Male territorial hooting. This call is<br />

primarily given by the male to promote pair<br />

formation, establish territory around a nest<br />

site, and in nest-showing. The female uncommonly<br />

gives a higher-pitched, harsher version<br />

with fewer notes, prior to egg laying. Captive.<br />

(Alaska, Leonard J. Peyton, ML 49945)<br />

106. Defensive or warning hooting. This call<br />

serves as a contact call between members <strong>of</strong> a<br />

breeding pair, <strong>of</strong>ten when intruders are near<br />

a nest site. It is sometimes given by the male<br />

when the female is <strong>of</strong>f the nest. (Oregon,<br />

David S. Herr, ML 48904)<br />

107. Defensive or warning hooting <strong>of</strong> an aggressive,<br />

highly agitated female. This call is <strong>of</strong><br />

a greater intensity than the previous call and directed<br />

towards a threat to the nest. It is given by<br />

both sexes. (Oregon, David S. Herr, ML 48904)<br />

16<br />

108. Male contact hoots announcing a prey<br />

delivery to the nest. A female g-wuk call<br />

is also audible. (Minnesota, Lang Elliott,<br />

6/14/93)<br />

109. Female contact call or whoop. The most<br />

common call given by the female, this vocalization<br />

is used for mate and family contact<br />

and as a food solicitation call from the nest. A<br />

red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) is also<br />

audible in this recording. (Oregon, David S.<br />

Herr, ML 47532)<br />

110. Female contact call or g-wuk. A variation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the call on Track 109. This female was<br />

soliciting food while in a nest. This call can<br />

vary greatly in intensity. Nestling begging<br />

calls are also audible. (Minnesota, Lang<br />

Elliott, 6/14/93)<br />

111. Chitter call <strong>of</strong> adult. This call is used<br />

in a variety <strong>of</strong> circumstances, most <strong>of</strong>ten by<br />

adults and juveniles during food transfers.<br />

It is also used to express discomfort, hunger,<br />

annoyance, and concern. Captive. (Alaska,<br />

Leonard J. Peyton, ML 49941)<br />

112. Distraction calls. A female uttered<br />

these calls during a distraction or injuryfeigning<br />

display near a nest. (Manitoba,<br />

Lang Elliott, 6/1/93)<br />

113. Agitated call by a female after a distraction<br />

display. (Manitoba, Lang Elliott, 6/1/93)<br />

114. Fledgling begging call interspersed by<br />

two exclamatory hoots that were probably<br />

given by the female. The owl uttered these<br />

hoots after it approached a vocalizing pine<br />

marten (Martes americana) which can be<br />

heard giving perturbed growls. Red squirrel<br />

(Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) is also audible.<br />

(Wyoming, Gregory F. Budney, ML 62945)<br />

115. Food exchange at nest site. First, a female<br />

utters the g-wuk food solicitation call<br />

and nestlings use chitter calls. A male flies in<br />

to a nearby tree, giving contact calls while the<br />

nestlings begin giving begging calls. As the<br />

male flies closer the intensity <strong>of</strong> the female’s<br />

g-wuk calls increases until she flies from the<br />

nest to receive prey from the male. At the<br />

time <strong>of</strong> food transfer, the male utters chitter<br />

calls and three deep hoots. The female returns<br />

to the nest. She and the nestlings utter chitter<br />

calls as food is transferred. The female also<br />

gives several s<strong>of</strong>ter squeals at the nest and<br />

during her return flight. (Minnesota, Lang<br />

Elliott, 6/14/93)<br />

116. Fledgling begging call. The howling <strong>of</strong><br />

coyote (Canis latrans) is also audible.<br />

(Wyoming, Gregory F. Budney, ML 62947)<br />

Gerrit Vyn

<strong>North</strong>ern Hawk Owl Surnia ulula<br />

A diurnal-crepuscular owl <strong>of</strong> the northern<br />

boreal forest, the <strong>North</strong>ern Hawk Owl is<br />

vocal and conspicuous during the breeding<br />

season. During that time, males sing from<br />

prominent perches within their territories,<br />

primarily around dawn and dusk. In a variety<br />

<strong>of</strong> contexts, both sexes utter various trilling<br />

calls that are similar to the male’s primary<br />

song. This species also has a wide repertoire <strong>of</strong><br />

alarm calls used around the nest. During the<br />

nonbreeding season, <strong>North</strong>ern Hawk <strong>Owls</strong><br />

are relatively quiet but do use several <strong>of</strong> the<br />

vocalizations described below.<br />

117. Male advertising song. This song may<br />

last up to 14 seconds and is <strong>of</strong>ten uttered in a<br />

display fight over the territory. The male also<br />

uses this song to advertise potential nest sites<br />

to the female. (Alaska, Leonard J. Peyton, ML<br />

49544)<br />

118. Trilling call. Both sexes use various<br />

trilling calls that are difficult to characterize.<br />

They use these calls in many contexts,<br />

including during nest disturbances. The male<br />

and female also utter trilling calls in duet during<br />

prey exchanges and copulation. (Alaska,<br />

Leonard J. Peyton, ML 49902)<br />

17<br />

119. Screeching call or screeee-yip followed<br />

by yelping call. Both sexes commonly issue<br />

these calls in alarm when an intruder is near a<br />

nest. They also use the screeching call widely<br />

in other contexts, including mate contact,<br />

food delivery, and female food solicitation.<br />

The yelping call is <strong>of</strong>ten uttered in flight, including<br />

during aerial attacks <strong>of</strong> potential nest<br />

predators. Nestling begging calls, similar to<br />

the adult screeching call, are audible in the<br />

background. (Alaska, Leonard J. Peyton, ML<br />

49954)<br />

120. Alarm squeals. An agitated owl near a<br />

nest uttered this call. It may be a distraction<br />

call. (Alaska, Leonard J. Peyton, ML 49910)<br />

121. Distress call. In winter, observers somtimes<br />

hear low-intensity versions <strong>of</strong> this call,<br />

given by alarmed owls. Captive. (Ontario,<br />

William W. H. Gunn, ML 61801)<br />

Gerrit Vyn

<strong>North</strong>ern Pygmy-Owl Glaucidium gnoma<br />

Heard throughout much <strong>of</strong> the coastal and<br />

mountain West, the diurnal-crepuscular<br />

<strong>North</strong>ern Pygmy-Owl sings most frequently<br />

near sunrise and sunset. It is also known to<br />

sing during the day. Songs <strong>of</strong> this species vary<br />

geographically and suggest that this species<br />

may be designated as several species in the<br />

future.<br />

[Note: The “chitter” calls described for<br />

<strong>North</strong>ern and Ferruginous pygmy-owls are<br />

not analogous to the chitter calls <strong>of</strong> other<br />

owl species. The use <strong>of</strong> the term “chitter” to<br />

describe pygmy-owl vocalizations may be the<br />

more appropriate usage. The term “discomfort<br />

call” may be more appropriate for describing<br />

the “chitter” in other owl species.]<br />

122. G.g. grinnelli. Male primary advertising<br />

or toot song. This is the common single-note<br />

song <strong>of</strong> the western coastal subspecies G.g.<br />

grinnelli. The primary song is <strong>of</strong>ten preceded<br />

by a trill which is not heard here. (Oregon,<br />

Ge<strong>of</strong>frey A. Keller, ML 105504)<br />

123. G.g. californicum. Male primary advertising<br />

or toot song. This is the common<br />

single-note song <strong>of</strong> the subspecies G.g. californicum.<br />

Found throughout much <strong>of</strong> the<br />

interior West, this subspecies is also known<br />

18<br />

to give a double-note song (not heard here).<br />

(Montana, Robert C. Faucett, ML 25653)<br />

124. G.g. gnoma. Male primary advertising<br />

or toot song. The subspecies G.g. gnoma,<br />

found in southeast Arizona and Mexico,<br />

typically sings a double-note song but will<br />

also sing a fast single-note song as heard here.<br />

(Arizona, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey A. Keller, ML 40576)<br />

125. G.g. gnoma. Male primary advertising<br />

or toot song. This is the typical double-note<br />

song <strong>of</strong> subspecies G.g. gnoma, or “Mountain<br />

Pygmy-Owl,” found in southeast Arizona and<br />

Mexico. (Arizona, L. Irby Davis, ML 9418)<br />

126. Male primary advertising song interspersed<br />

with prolonged chitter call. S<strong>of</strong>t<br />

female chitter calls can be heard which<br />

initiate the male’s use <strong>of</strong> the prolonged<br />

chitter. The behavioral context for this recording<br />

is unknown, although it seems<br />

to indicate a level <strong>of</strong> sexual excitement. It<br />

is probably analogous to the Ferruginous<br />

Pygmy-Owl sequence heard on Track 134.<br />

(Arizona, Frederick R. Gehlbach, 4/2/00)<br />

127. Female chitter call. (Arizona, Frederick<br />

R. Gehlbach, 4/2/00)<br />

128. Copulation calls. (Colorado, Robert<br />

Righter, 6/97)<br />

129. Food delivery at a nest.<br />

In this sequence the male<br />

gives several toots to announce<br />

a delivery. The female comes<br />

out <strong>of</strong> the nest, uttering chitter<br />

calls. She receives the<br />

food and returns to the nest<br />

cavity. (Arizona, Frederick R.<br />

Gehlbach, 2000)<br />

130. Female chitter call followed<br />

by an unknown call.<br />

The voice <strong>of</strong> a researcher is<br />

briefly heard at the end <strong>of</strong> this<br />

recording. (Arizona, Bernard<br />

Lohr, 6/6/00)<br />

131. Fledgling begging call.<br />

(Washington, Charles A.<br />

Sutherland, ML 9419)<br />

Jared Hobbs

Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl Glaucidium brasilianum<br />

A diurnal-crepuscular owl <strong>of</strong> extreme southern<br />

Arizona and Texas, the Ferruginous<br />

Pygmy-Owl is a common bird south <strong>of</strong> the<br />

border. It sings most frequently near dawn<br />

and dusk but also during the day and occasionally<br />

at night. Its song varies widely in<br />

volume, frequency, and duration. Both males<br />

and females use a version <strong>of</strong> the primary advertising<br />

song, with the females’ voices higher<br />

and sweeter. Researchers have proposed that<br />

this species should be split into two species,<br />

with the birds occurring in the United States<br />

referred to as Ridgway’s Pygmy-Owl<br />

(Glaucidium ridgwayi).<br />

132. Male primary advertising or territorial<br />

song. (Texas, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey A. Keller, ML 105563)<br />

133. Female primary advertising or territorial<br />

song. (Arizona, Greg Clark and Tim Price,<br />

2/02)<br />

134. Male primary advertising song interspersed<br />

with prolonged chitter calls. The<br />

female utters s<strong>of</strong>t chitter calls that seem to<br />

initiate the male’s use <strong>of</strong> the prolonged chitter.<br />

The behavioral context for this recording<br />

is unknown, although it seems to indicate<br />

sexual excitement. It is probably analogous to<br />

the <strong>North</strong>ern Pygmy-Owl sequence on Track<br />

125. (Mexico, Andres M. Sada, FMNH<br />

1019)<br />

19<br />

135. Female chitter call. The female uses<br />

this vocalization as a food solicitation call.<br />

She uses a shortened chitter as a contact call.<br />

It is derived from the fledgling begging call.<br />

(Texas, Glenn A. Proudfoot, 6/99)<br />

136. Female alarm or pee-weeet call. Females<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten use this call when human intruders are<br />

near the nest. (Texas, Glenn A. Proudfoot,<br />

6/99)<br />

137. Female aggression call. The owls utter<br />

this call in mild agitation when intruders<br />

approach the nest and in response to other<br />

Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl songs near the nest<br />

site. This call is commonly given by females,<br />

less <strong>of</strong>ten by males. (Texas, Glenn A.<br />

Proudfoot, 4/98)<br />

138. Female aggression call. (Arizona, Greg<br />

Clark and Tim Price, 2/02)<br />

139. Nestling distress call. (Texas, Glenn A.<br />

Proudfoot)<br />

140. Fledgling begging chitter. The calls <strong>of</strong><br />

Western Tanager (Piranga ludoviciana) are<br />

also prominent. (Texas, Glenn A. Proudfoot)<br />

Gerrit Vyn

Elf Owl Micrathene whitneyi<br />

<strong>North</strong> America’s smallest owl, this species<br />

is a common spring singer in parts <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Southwest. Although they are <strong>of</strong>ten associated<br />

with giant saguaro cacti, Elf Owl can be<br />

heard wherever suitable woodpecker cavities<br />

can be found for nesting. This includes many<br />

areas familiar to birders in southeast Arizona,<br />

where riparian sycamores and cottonwoods<br />

provide nest sites.<br />

141. Male chatter song and female station<br />

call. The male uses the chatter song for territorial<br />

advertisement and defense as well as to<br />

attract a mate. It is most <strong>of</strong>ten heard at dusk<br />

and dawn during the period <strong>of</strong> nest-site selection<br />

and pair formation in April and May.<br />

Both sexes use the station call as a contact call<br />

between mates and young. (Arizona, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey<br />

A. Keller, ML 40636)<br />

142. Prolonged male chatter song and<br />

female calls. Males utter this song from<br />

within a potential nest cavity or its immediate<br />

vicinity to lure the female to the cavity.<br />

Its intensity increases as the female responds<br />

or approaches. Various female calls can also<br />

be heard, including a cricket-like twitter in<br />

flight. (Arizona, Bernard Lohr, 5/7/01)<br />

143. Bark call and station call given by pair.<br />

The bark call is an alarm call or scolding call<br />

20<br />

directed at intruders, including humans, near<br />

the nest site. Used by both sexes, it varies in<br />

intensity depending on the owl’s level <strong>of</strong> agitation<br />

or alarm. A second bird can be heard<br />

giving the station call midway through the<br />

recording. (Arizona, Bernard Lohr, 6/6/00)<br />

144. Bark call. (Arizona, William W. H.<br />

Gunn, ML 59816)<br />

145. Copulation calls. (Arizona, J. David<br />

Ligon, ML 42361)<br />

146. Nestling begging rasp. (Arizona,<br />

Harriette Barker, ML 25169)<br />

Brian E. Small

Burrowing Owl Athene cunicularia<br />

Considered an accomplished vocalist, the<br />

Burrowing Owl is known to have a large repertoire<br />

<strong>of</strong> calls beyond those presented here.<br />

Its calls are well known, partly because <strong>of</strong> its<br />

diurnal activities and open country habitat,<br />

which have provided researchers with good<br />

opportunities for direct observation <strong>of</strong> vocalizing<br />

birds. Burrowing <strong>Owls</strong> are most active<br />

vocally in the spring, though courtship and<br />

alarm calls can be heard throughout the year.<br />

147. Male primary or courtship song. The<br />

male uses this song in the vicinity <strong>of</strong> the nest<br />

burrow. This territorial or advertisement song<br />

is accompanied by the bowing display.<br />

(California, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey A. Keller, ML 119481)<br />

148. Alarm chatter. Burrowing <strong>Owls</strong> use this<br />

call in nest defense or predator mobbing. It<br />

varies in intensity and duration. (California,<br />

Ge<strong>of</strong>frey A. Keller, ML 118856)<br />

149. Single alarm notes and alarm chatter.<br />

(Alberta, Albert Karvonen, ML 59807)<br />

150. Alarm chatter at burrow. (California,<br />

Gregory F. Budney, ML 126498)<br />

151. Nestling begging rasp and adult alarm<br />

chatter at burrow. (California, Gregory F.<br />

Budney, ML 126498)<br />

21<br />

152. Juvenile alarm call or rattlesnake rasp.<br />

When highly distressed, young owls utter<br />

this call from the nest burrow. It is believed<br />

to mimic the rattle <strong>of</strong> a rattlesnake (Crotalis<br />

spp.) to deter potential predators. Threatened<br />

adults sometimes produce a more convincing<br />

version. (Idaho, Jeffrey Rice, 6/22/04)<br />

Gerrit Vyn

Boreal Owl Aegolius funereus<br />

In recent years, the detection <strong>of</strong> singing and<br />

calling Boreal <strong>Owls</strong> has led to the discovery<br />

that Boreal <strong>Owls</strong> breed in many subalpine<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> the West as far south as New Mexico.<br />

Previously they were thought to breed only in<br />

the boreal forests. The male’s song is primarily<br />

heard in late winter and early spring prior<br />

to egg-laying. Unpaired males may continue<br />

singing into summer. Some <strong>of</strong> the Boreal<br />

Owl’s calls are very similar to those <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>North</strong>ern Saw-whet Owl.<br />

153. Male primary or staccato song. This song<br />

serves as a long distance advertisement to<br />

potential mates and is usually given in the<br />

vicinity <strong>of</strong> potential nest cavities. Some listeners<br />

have confused this song with the winnowing <strong>of</strong><br />

Wilson’s Snipe (Gallinago delicata). (Alaska,<br />

Leonard J. Peyton, ML 49540)<br />

154. Male prolonged staccato song. The male<br />

uses this song to advertise a nest cavity when the<br />

female is present. The male may fly to and from<br />

a potential nest cavity and the female, giving<br />

the prolonged song in flight and from the cavity<br />

itself. Males <strong>of</strong>ten switch from the primary song<br />

to the prolonged song when the female appears.<br />

The song, which facilitates pair formation, is delivered<br />

s<strong>of</strong>tly compared with the primary song.<br />

(Minnesota, Steven G. Wilson, 6/89)<br />

22<br />

155. Male subdued staccato song or brief<br />

trill. Males utter a subdued version <strong>of</strong> the<br />

primary song in many instances. It is <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

heard prior to, after, or between long bouts <strong>of</strong><br />

the primary song. It is also sometimes used as<br />

the initial vocalization during a food delivery.<br />

(Minnesota, Steven G. Wilson, 6/89)<br />

156. Skiew call or screech. Both sexes use<br />

this variable call in a wide variety <strong>of</strong> contexts.<br />

Often delivered quite loudly, it commonly<br />

ends in a bill-clap. It is used year round and<br />

is <strong>of</strong>ten heard in response to broadcast <strong>of</strong> the<br />

primary song. It may serve as a contact call or<br />

a warning call, or it may suggest annoyance.<br />

(Minnesota, Steven G. Wilson, 6/89)<br />

157. Food delivery or moo-a call. The male<br />

uses this variable call to announce food deliveries<br />

to the nest or fledglings. Calls similar<br />

to this are also heard in response to broadcast<br />

<strong>of</strong> the primary song. (Minnesota, Steven G.<br />

Wilson, 6/89)<br />

158. Nestling peep and male food delivery<br />

call. (Minnesota, Steven G. Wilson, 6/89)<br />

159. Nestling chatter and female peep call<br />

from the nest. The female uses the peep call<br />

widely during the breeding season when soliciting<br />

food from the male or as a contact call.<br />

This call is derived from the juvenile begging<br />

call. (Alaska, Rosa Meehan,<br />

BLB 22369)<br />

160. Fledgling begging call<br />

or peep, male food delivery<br />

call, and a s<strong>of</strong>t skiew call.<br />

The winnowing <strong>of</strong> Wilson’s<br />

Snipe (Gallinago delicata)<br />

is also audible. (Minnesota,<br />

Steven G. Wilson, 6/89)<br />

Gerrit Vyn

<strong>North</strong>ern Saw-whet Owl Aegolius acadicus<br />

The diminutive <strong>North</strong>ern Saw-whet Owl is<br />

most conspicuous during the brief period from<br />

February through April when most male singing<br />

occurs. Throughout the rest <strong>of</strong> the year this<br />

species is heard infrequently or may be unrecognized<br />

by observers. The ksew call is a variable<br />

call that can be confused with the skiew<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Boreal Owl. This species is named for its<br />

“saw-whet” call, but there is much debate over<br />

which vocalization this refers to.<br />

161. Male advertising song. <strong>North</strong>ern<br />

Saw-whet <strong>Owls</strong> use this monotonous song in<br />

territorial establishment and mate attraction.<br />

The male sometimes sings it from prospective<br />

nest holes. The female sometimes sings a s<strong>of</strong>ter,<br />

less-consistent version. (Oregon, Ge<strong>of</strong>frey<br />

A. Keller, ML 42199)<br />