26 September programme - London Symphony Orchestra

26 September programme - London Symphony Orchestra

26 September programme - London Symphony Orchestra

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

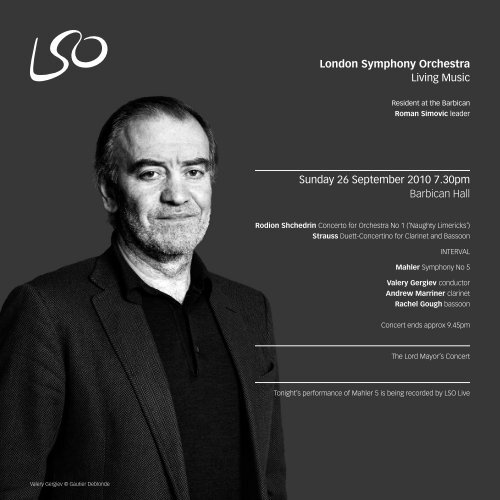

Valery Gergiev © Gautier Deblonde<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Living Music<br />

Resident at the Barbican<br />

Roman Simovic leader<br />

Sunday <strong>26</strong> <strong>September</strong> 2010 7.30pm<br />

Barbican Hall<br />

Rodion Shchedrin Concerto for <strong>Orchestra</strong> No 1 (‘Naughty Limericks’)<br />

Strauss Duett-Concertino for Clarinet and Bassoon<br />

INTERVAL<br />

Mahler <strong>Symphony</strong> No 5<br />

Valery Gergiev conductor<br />

Andrew Marriner clarinet<br />

Rachel Gough bassoon<br />

Concert ends approx 9.45pm<br />

The Lord Mayor’s Concert<br />

Tonight’s performance of Mahler 5 is being recorded by LSO Live

Welcome From The Lord Mayor<br />

Welcome to the second of the LSO’s opening concerts of<br />

the 2010/11 season, conducted by the <strong>Orchestra</strong>’s Principal<br />

Conductor Valery Gergiev.<br />

As many of you will know, the LSO and the Cricket Foundation are<br />

the principal beneficiary charities of the 2010 Lord Mayor’s Appeal.<br />

I am delighted to welcome The Lord Mayor, Alderman Nick Anstee,<br />

to tonight’s concert; on behalf of everyone at the LSO, I would like to<br />

thank him for proposing that music and cricket could come together<br />

in this way to benefit young people. Turn to page 12 to read more<br />

about what the appeal has achieved over the last 12 months – and<br />

don’t forget, there’s still time to donate!<br />

Tonight’s concert continues Valery Gergiev’s survey of the works<br />

of his compatriot, Rodion Shchedrin. We are honoured that Rodion<br />

Shchedrin is with us tonight and look forward to discovering more of<br />

his music later this season.<br />

Tonight, two of the <strong>Orchestra</strong>’s long-standing members, Principal<br />

Clarinet Andrew Marriner and Principal Bassoon Rachel Gough, take<br />

centre stage in Richard Strauss’s charming Duett-Concertino.<br />

After the interval, the <strong>Orchestra</strong> performs Mahler’s Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong>,<br />

marking the start of a season in which the LSO and Valery Gergiev will<br />

perform Mahler symphonies world-wide.<br />

Kathryn McDowell<br />

LSO Managing Director<br />

It is a pleasure to welcome you all to the Lord Mayor’s annual<br />

concert with the LSO, the <strong>Orchestra</strong> of the City. The City of <strong>London</strong><br />

Corporation is proud to support this world class ensemble in<br />

its residency at the Barbican and also recognises its role as an<br />

international ambassador for the City.<br />

This year I have chosen LSO Discovery’s On Track <strong>programme</strong> as one<br />

of the principal beneficiaries of my charitable Appeal, Pitch Perfect.<br />

Together with the Cricket Foundation’s StreetChance <strong>programme</strong>,<br />

Pitch Perfect aims to generate significant funds to bring musical<br />

and cricketing opportunities into schools and their communities in<br />

<strong>London</strong>’s most challenging boroughs. You will find a brochure on<br />

your seats tonight which explains more fully the work of these two<br />

wonderful organisations that are working to reach 75,000 children<br />

over the next five years.<br />

I wish you a very enjoyable evening and if the music touches you<br />

tonight, please consider supporting the musicians of the future<br />

through Pitch Perfect.<br />

Nick Anstee<br />

Lord Mayor of the City of <strong>London</strong><br />

Rodion Shchedrin (b 1932)<br />

Concerto for <strong>Orchestra</strong> No 1 (‘Naughty Limericks’) (1963)<br />

Shchedrin is one of very few composers for whom the concerto for<br />

orchestra has been more than a one-off event. Some, such as the<br />

Italian Goffredo Petrassi, who composed eight examples between the<br />

1930s and 1970s, have followed Hindemith’s cue, producing frankly<br />

recreational music, designed primarily to show off the qualities of<br />

the modern orchestra. Others, such as Shchedrin’s compatriot and<br />

near-contemporary Alfred Schnittke, have preferred the closely related<br />

genre of concerto grosso, deriving inspiration principally from the<br />

fusion of old and new styles.<br />

In Shchedrin’s five concertos for orchestra to date, there is a bit of<br />

both those trends. Each work carries a subtitle referring to an aspect<br />

of traditional Russian culture, and at the same time each showcases<br />

the possibilities of the contemporary orchestra. The first was<br />

composed in 1963 and premiered that year at the Warsaw Autumn<br />

Festival under Gennady Rozhdestvensky. Soon taken up in the United<br />

States by Bernstein, it has gone on to become one of Shchedrin’s<br />

most widely heard scores.<br />

Replete with witty musical tricks, including honky-tonk piano and a<br />

naughty-boy final cadence, this eight-minute tour de force is a riot<br />

of colourful incident – something like Malcolm Arnold crossed with<br />

Charles Ives, perhaps, with nods to Copland, Penderecki and western<br />

pop along the way. Pre-empting any attempts at more sophisticated<br />

analysis, Shchedrin has summed up the form as ‘like many variations<br />

on many themes’.<br />

The subtitle ‘Naughty Limericks’ points to roots in folk culture, as if to<br />

remind Soviet authorities that subversiveness and high spirits could<br />

in fact be politically correct. In fact ‘Limericks’ is a loose rendition<br />

of the untranslatable Russian chastushki, which denotes animated,<br />

humorous village songs, sometimes with indecent texts and often<br />

improvised around only a few notes. This was a 20th-century genre<br />

rather than one with a long history, and as the composer later<br />

stressed, ‘even hallowed names such as Marx, Lenin and Stalin<br />

could be sent up in the chastushka’. Had the political climate of the<br />

1960s allowed it, he would have chosen the adjective rugatel’nïye<br />

(‘indecent’) rather than ozornïye (literally ‘mischievous’), or so he<br />

claimed.<br />

In this modern reincarnation of the chastushka it is as though, inspired<br />

by the sensational return visit of Stravinsky to his homeland the<br />

previous year, Shchedrin was imagining what the Stravinsky of the<br />

1910s might have gone on to compose had he never emigrated, and<br />

had he not deflected from his Russian roots into cool, cosmopolitan<br />

neoclassicism.<br />

Programme note and profile © David Fanning<br />

David Fanning is Professor of Music at the University of Manchester.<br />

He is an expert on Shostakovich, Nielsen and Soviet music. He is also<br />

a reviewer for the Daily Telegraph, Gramophone Magazine and<br />

BBC Radio 3.<br />

I still today continue to be convinced that<br />

the decisive factor for each composition is<br />

intuition. As soon as composers relinquish<br />

their trust in this intuition and rely in its<br />

place on musical ‘religions’ such as serialism,<br />

aleatoric composition, minimalism or<br />

other methods, things become problematic.<br />

Rodion Shchedrin<br />

Music’s better shared!<br />

There’s never been a better time to bring your friends to an LSO<br />

concert. Groups of 10+ receive a 20% discount on all tickets, plus a<br />

host of additional benefits. Call the dedicated Group Booking line on<br />

020 7382 7211, visit lso.co.uk/groups, or email<br />

groups@barbican.org.uk.<br />

The LSO is delighted to welcome the following group tonight:<br />

Inscape Study Tours<br />

2 Welcome<br />

Kathryn McDowell © Camilla Panufnik Programme Notes 3

Rodion Shchedrin & Valery Gergiev<br />

Russian Compatriots<br />

Rodion Shchedrin<br />

Valery Gergiev<br />

1945–50<br />

Joined the<br />

Moscow<br />

Choral School<br />

16 Dec 1932<br />

Born, Moscow<br />

1950–55<br />

Trained at<br />

the Moscow<br />

Conservatory<br />

1958<br />

Married<br />

ballerina Maya<br />

Plisetskaya<br />

2 May 1953<br />

Born, Moscow<br />

Valery Gergiev’s Rodion Shchedrin<br />

1960<br />

The Little<br />

Humpbacked<br />

Horse, Moscow<br />

1961<br />

Not only love,<br />

Moscow<br />

1963<br />

Naughty Limericks,<br />

Warsaw<br />

Fri 19 Nov 2010 Piano Concerto No 4 (‘Sharp Keys’) with Olli Mustonen<br />

Wed 23 & Thu 24 Mar 2011 Lithuanian Saga<br />

1964–69<br />

Professor of Composition,<br />

Moscow Conservatory<br />

1967<br />

Carmen Suite,<br />

Moscow<br />

1968<br />

The Chimes,<br />

New York<br />

1969<br />

Becomes freelance<br />

composer<br />

1968<br />

Refused to sign open<br />

letter sanctioning the<br />

invasion of Warsaw Pact<br />

troops in Czechoslovakia<br />

1972<br />

Anna Karenina,<br />

Moscow<br />

1973<br />

Succeeds Shostakovich<br />

as President of the Union<br />

of Composers of the<br />

Russian Federation<br />

1972<br />

Receives the USSR<br />

State Prize<br />

1960 1970 1980 1990 2000<br />

1972–77<br />

Trained at the Leningrad<br />

Conservatory<br />

1977<br />

Dead Souls,<br />

Moscow<br />

1976<br />

Wins Herbert von Karajan<br />

Conducting Competition,<br />

Berlin<br />

1977<br />

Appointed Assistant<br />

Conductor to Kirov<br />

Opera<br />

1978<br />

Kirov debut<br />

– War and<br />

Peace<br />

1981–85<br />

Appointed Chief<br />

Conductor of the<br />

Armenian Philharmonic<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

1989<br />

Khorovody,<br />

Tokyo<br />

1985<br />

Honorary member of the<br />

International Music Council<br />

1983<br />

Honorary member of the<br />

Academy of Fine Arts, GDR<br />

1984<br />

Receives the Lenin Prize<br />

4 Programme Notes Programme Notes 5<br />

1985<br />

UK debut at the<br />

Lichfi eld Festival<br />

1988<br />

The Sealed<br />

Angel,<br />

Moscow<br />

1988<br />

LSO debut<br />

1989<br />

Member of Berlin<br />

Arts Academy<br />

1988<br />

Appointed Chief<br />

Conductor and<br />

Artistic Director<br />

of the Mariinsky<br />

Theatre<br />

1990<br />

Old Russian Circus<br />

Music, Chicago<br />

1991<br />

USA debut with<br />

War and Peace<br />

1994<br />

Lolita, Stockholm;<br />

Sotto voce Concerto,<br />

<strong>London</strong>;<br />

Trumpet Concerto,<br />

Pittsburgh<br />

1993<br />

Receives Dmitri<br />

Shostakovich Prize<br />

1998<br />

Four Russian Songs,<br />

<strong>London</strong><br />

1997<br />

Honorary Professor,<br />

Moscow Conservatory<br />

1997<br />

Receives Dmitri<br />

Shostakovich Prize<br />

1998<br />

Fifth Piano Concerto,<br />

Los Angeles<br />

1999<br />

Marries Natalya Debisova<br />

1995–2008<br />

Appointed Principal Conductor<br />

of the Rotterdam Philharmonic<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

1996<br />

Russian government appoints<br />

him overall Director of the<br />

Mariinsky Theatre<br />

1997<br />

Appointed Principal Guest<br />

Conductor of the Metropolitan<br />

Opera, New York<br />

2002<br />

Dialogues with<br />

Shostakovich,<br />

Pittsburgh<br />

2003<br />

Sixth Piano Concerto,<br />

Amsterdam<br />

2002<br />

Order for Service to<br />

the Russian State:<br />

Third Degree<br />

2005<br />

2008<br />

Honorary Professor, Honorary Professor,<br />

St Petersburg State Central Conservatory<br />

Conservatory of Music, Beijing<br />

2003<br />

UNESCO Artist for Peace<br />

2003<br />

Order for Service to the<br />

Russian State: Third Degree<br />

2003<br />

First performance<br />

of Wagner’s Ring in<br />

Russia for 90 years<br />

2006<br />

Boyarina Morozova,<br />

Moscow<br />

2007<br />

Order for Service to<br />

the Russian State:<br />

Fourth Degree<br />

2006<br />

Opens the new<br />

Mariinsky Concert<br />

Hall<br />

2008<br />

Order for Service to<br />

the Russian State:<br />

Fourth Degree<br />

2004<br />

2007<br />

Second appearance Takes Mariinsky<br />

with the LSO Wagner’s Ring to<br />

New York<br />

2005<br />

Appointed 15th Principal<br />

Conductor of the LSO<br />

(fi rst offi cial concert<br />

23 Jan 07)<br />

2010<br />

Named one of the 100 Most<br />

Infl uential People in the World<br />

by Time magazine

Rodion Shchedrin<br />

The Man<br />

The generation of Soviet composers after Shostakovich produced<br />

charismatic and exotic figures such as Galina Ustvolskaya, Alfred<br />

Schnittke and Sofiya Gubaydulina, whose music was initially<br />

controversial but then gained cult status. At the other end of the<br />

stylistic spectrum it featured highly gifted craftsmen such as Boris<br />

Tishchenko, Boris Chaykovsky and Mieczysław Weinberg, all of whom<br />

worked more or less within the parameters laid down by Shostakovich<br />

and were highly respected in their heyday but gradually fell from<br />

favour.<br />

Somewhere in between we can locate Rodion Shchedrin – an<br />

individualist with a broader and more consistent appeal, who could<br />

turn himself chameleon-like to virtuoso pranks or to profound<br />

philosophical reflection, to Socialist Realist opera or to folkloristic<br />

concertos for orchestra (a particular speciality), to technically solid<br />

preludes and fugues, to jazz, and, when he chose, even to twelve-note<br />

constructivism.<br />

Trained at Moscow Conservatoire in the 1950s, as a composer under<br />

Yuri Shaporin and as a pianist under Yakov Flier, in the early<br />

years of the Post-Stalinist Thaw Shchedrin was one of<br />

the first to speak out against the constraints of<br />

musical life in the Soviet Union. He went on to play<br />

a significant administrative role in the country’s<br />

musical life, heading the Russian Union of Composers<br />

from 1973 to 1990. Married since 1958 to the star<br />

Soviet ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, he established a<br />

significant power-base from which he was able to promote<br />

not only his own music but also that of others – such as<br />

Schnittke, whose notorious First <strong>Symphony</strong> received its<br />

sensational premiere only thanks to Shchedrin’s support.<br />

An unashamed eclectic, and suspicious of dogma from<br />

either the arch-modernist or arch-traditionalist wings of<br />

Soviet music, Shchedrin occupied a not always comfortable<br />

position, both in his pronouncements and in his creative<br />

work. With one foot in the national-traditional camp and the<br />

other in that of the internationalist-progressives, he was<br />

tagged with the unkind but not unfair label of the USSR’s<br />

6 Programme Notes<br />

‘official modernist’. From 1992 he established a second<br />

home in Munich, but he still enjoyed official favour in post-Soviet<br />

Russia, adding steadily to his already impressive roster of prizes.<br />

Shchedrin has summed up his artistic credo as follows: ‘I continue<br />

to be convinced that the decisive factor for each composition<br />

is intuition. As soon as composers relinquish their trust in this<br />

intuition and rely in its place on musical ‘religions’ such as serialism,<br />

aleatoric composition, minimalism or other methods, things become<br />

problematic.’<br />

Rodion Shchedrin © www.lebrecht.co.uk<br />

Richard Strauss (1864–1949)<br />

Duett-Concertino for Clarinet, Bassoon, Strings and Harp (1947)<br />

Allegro moderato –<br />

Andante –<br />

Rondo: allegro non troppo<br />

Andrew Marriner clarinet<br />

Rachel Gough bassoon<br />

Strauss’s last work for orchestra is a lovely example of the serene and<br />

apparently effortless creativity characteristic of the ‘Indian Summer’<br />

of his 80s. In exile in Switzerland – life in Germany in the first years<br />

after the end of the war was very difficult for him – he wrote the<br />

Duett-Concertino for the chamber orchestra of the Italian-Swiss Radio<br />

in Lugano, where it was first performed in April 1948. The soloists on<br />

that occasion were the principal clarinet and bassoon of the Swiss<br />

ensemble, although the score is actually dedicated to<br />

Hugo Burghauser, a Vienna Philharmonic bassoonist who had<br />

emigrated to New York. Writing to Burghauser with the dedication,<br />

Strauss revealed that there is a story behind the work: a dancing<br />

princess is alarmed by the grotesque attentions of a bear who<br />

however, when she dances with him, turns out to be a prince.<br />

‘So you too, Burghauser,’ the composer added, ‘become a prince<br />

at last and everything ends happily.’<br />

Constructed in three movements performed without a break, the<br />

Concertino makes complete musical sense without reference to any<br />

beauty-and-the-beast kind of scenario – not least because it is so<br />

firmly held together by the little five-note flourish introduced by a<br />

sextet of solo strings in the opening bars. Even so, since the storyline<br />

is so clearly and at the same time so poetically presented, it is<br />

tempting to follow the interaction of the two principal characters<br />

through at least the first two movements. After the string sextet<br />

introduction with the all-important five-note flourish, the clarinetprincess<br />

makes a beautifully poised entry on an exquisitely supple<br />

line. The bassoon-bear on its first appearance, though far from<br />

beastly, is certainly gruff enough to cause alarm, as is clear from the<br />

distressed gestures of the clarinet and the agitation of the strings.<br />

The bassoon is not lacking in plaintive eloquence, however, and the<br />

following exchanges, while by no means amorous, are animatedly<br />

conversational. This episode ends with the clarinet recalling its first<br />

melody, now doubled by a solo violin, while the bassoon adds its<br />

comments below.<br />

If there is a moment when the bear is transformed into a prince, it is<br />

in the transition to the second movement, where the magical sounds<br />

of high tremolando strings and splashing harp precede one of the<br />

most expressive soliloquies ever written for bassoon. The clarinet<br />

cannot resist it, first adding a pretty counterpoint then joining in close<br />

harmony before the two soloists swap cadenzas and decide that the<br />

five-note flourish (which has never been absent for very long) will be<br />

the thematic basis of their life together in the next movement.<br />

That theme, re-introduced upside down by the bassoon and the right<br />

way up by the clarinet, is the thread that guides the ear through the<br />

maze-like design of the finale. Amid all the sparkling repartee, the<br />

constant variations on the main theme and the allusions to earlier<br />

movements, there are two particularly significant events – the entry<br />

of a new, lyrical melody introduced by the clarinet and bassoon in<br />

unison and a recall of the same melody now rapturously supported<br />

by violins – which both give the movement a clear shape, and confirm<br />

the compatibility of the two protagonists.<br />

Programme note © Gerald Larner<br />

While specialising in French music, Gerald Larner writes extensively<br />

on most areas of the repertoire. He has been appointed Officier dans<br />

l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government.<br />

When you work with somebody for years you<br />

like to think you can second guess them.<br />

But there will always be surprises, and that is<br />

what makes music come to life.<br />

Rachel Gough on working with<br />

Andrew Marriner<br />

Programme Notes<br />

7

Gustav Mahler (1860–1911)<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> No 5 (1901–2)<br />

Part I<br />

Funeral March: In gemessenem Schritt. Streng. Wie ein Kondukt. [With<br />

measured tread. Strict. Like a procession]<br />

Sturmisch bewegt. Mit grösster Vehemenz [Stormy. With utmost<br />

vehemence]<br />

Part II<br />

Scherzo: Kräftig, nicht zu schnell. [Vigorous, not too fast]<br />

Part III<br />

Adagietto: Sehr langsam [Very slow]<br />

Rondo-Finale: Allegro<br />

Mahler began his Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong> in 1901. This had been a turbulent<br />

year: in February, after a near-fatal haemorrhage, Mahler had resigned<br />

as conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic <strong>Orchestra</strong>; at about the<br />

same time he met his future wife, Alma Schindler, and fell passionately<br />

in love. All this seems to have left its mark on the Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong>’s<br />

character and musical argument. But as Mahler was at pains to<br />

point out, that doesn’t ultimately give us the ‘meaning’ of the Fifth<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong>. For that one has to look directly at the music. The first<br />

movement is a grim Funeral March, opening with a trumpet fanfare,<br />

quiet at first but growing menacingly. At its height, the full orchestra<br />

thunders in with an unmistakable funereal tread. Shuddering string<br />

trills and deep, rasping horn notes evoke death in full grotesque pomp.<br />

Then comes a more intriguing pointer: the quieter march theme that<br />

follows is clearly related to Mahler’s song ‘Der Tambourg’sell’ (‘The<br />

Drummer Lad’), which tells of a pitiful young deserter facing execution<br />

– no more grandeur, just pity and desolation.<br />

Broadly speaking, the second movement is an urgent, sometimes<br />

painful struggle. The shrill three-note woodwind figure near the<br />

start comes to embody the idea of striving. Several times aspiration<br />

falls back into sad rumination. At last the striving culminates in a<br />

radiant brass hymn tune, with ecstatic interjections from the rest<br />

of the orchestra. Is the answer to death to be found in religious<br />

consolation? But the affirmation is unstable, and the movement<br />

quickly fades into darkness.<br />

Now comes a surprise. The Scherzo bursts onto the scene with a<br />

wildly elated horn fanfare. The character is unmistakably Viennese<br />

– a kind of frenetic waltz. But the change of mood has baffled some<br />

writers: the Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong> has even been labelled ‘schizophrenic’.<br />

Actually ‘manic depressive’ might be more appropriate. Many<br />

psychologists now believe that the over-elated manic phase<br />

represents a deliberate mental flight from unbearable thoughts or<br />

situations, and certainly there are parts of this movement where the<br />

gaiety sounds forced, even downright crazy. Mahler himself wondered<br />

what people would say ‘to this primeval music, this foaming, roaring,<br />

raging sea of sound?’ Still Mahler cunningly bases the germinal<br />

opening horn fanfare on the three-note ‘striving’ figure from the<br />

second movement: musically the seeming disunity is only skin-deep.<br />

Now comes the famous Adagietto, for strings and harp alone, and<br />

another profound change of mood. Mahler, the great Lieder composer,<br />

clearly intended this movement as a kind of wordless love-song to<br />

his future wife, Alma. Here he quotes from one of his greatest songs,<br />

‘Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen’ (‘I am lost to the world’) from<br />

his Rückert Lieder. The poem ends with the phrase ‘I live alone in my<br />

heaven, in my love, in my song’; Mahler quotes the violin phrase that<br />

accompanies ‘in my love, in my song’ at the very end of the Adagietto.<br />

This invocation of human love and song provides the true turning<br />

point in the Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong>. The finale is a vigorous, joyous<br />

contrapuntal display – genuine joy this time. Even motifs from the<br />

Adagietto are drawn into the bustling textures. Finally, after a long<br />

and exciting build-up, the second movement’s brass chorale returns<br />

in full splendour, now firmly anchored in D major, the symphony’s<br />

home key. The triumph of faith, hope and love? Not everyone finds<br />

this ending convincing; Alma Mahler had her doubts from the<br />

very beginning. But one can hear it either as a ringing affirmation<br />

or strained triumphalism and it still stirs. For all his apparent lateromanticism,<br />

Mahler was also a very modern composer: even in his<br />

most positive statements there is room for doubt.<br />

Programme note © Stephen Johnson<br />

Stephen Johnson contributes regularly to BBC Music Magazine and<br />

The Guardian, and broadcasts for BBC Radio 3 (BBC Legends and<br />

Discovering Music), Radio 4 and the World Service.<br />

Richard Strauss (1864–1949)<br />

Composer Profile<br />

Richard Strauss was born in Munich in 1864, the son of Franz Strauss,<br />

a brilliant horn player in the Munich court orchestra; it is therefore<br />

perhaps not surprising that some of the composer’s most striking<br />

writing is for the French horn. Strauss had his first piano lessons when<br />

he was four, and he produced his first composition two years later, but<br />

surprisingly he did not attend a music academy; his formal education<br />

ending rather at Munich University where he studied philosophy and<br />

aesthetics, continuing with his musical training at the same time.<br />

Following the first public performances of his work, he received a<br />

commission from Hans von Bülow in 1882 and two years later was<br />

appointed Bülow’s Assistant Musical Director at the Meiningen Court<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, the beginning of a career in which Strauss was to conduct<br />

many of the world’s great orchestras, in addition to holding positions<br />

at opera houses in Munich, Weimar, Berlin and Vienna. While at<br />

Munich, he married the singer Pauline de Ahna, for whom he wrote<br />

many of his greatest songs.<br />

Strauss’s legacy is to be found in his operas and his magnificent<br />

symphonic poems. Scores such as Till Eulenspiegel, Also sprach<br />

Zarathustra, Don Juan and Ein Heldenleben demonstrate his supreme<br />

mastery of orchestration; the thoroughly modern operas Salome and<br />

Elektra, with their Freudian themes and atonal scoring, are landmarks<br />

in the development of 20th -century music, and the neo-Classical<br />

Der Rosen kavalier has become one of the most popular operas<br />

of the century. Strauss spent his last years in self-imposed exile in<br />

Switzerland, waiting to be officially cleared of complicity in the Nazi<br />

regime. He died at Garmisch Partenkirchen in 1949, shortly after his<br />

widely celebrated 85th birthday.<br />

Gustav Mahler (1860–1911)<br />

Composer Profile<br />

Gustav Mahler’s early experiences of music were influenced by the<br />

military bands and folk singers who passed by his father’s inn in the<br />

small town of Iglau. Besides learning many of their tunes, he also<br />

received formal piano lessons from local musicians and gave his first<br />

recital in 1870. Five years later, he applied for a place at the Vienna<br />

Conservatory where he studied piano, harmony and composition.<br />

After graduation, Mahler supported himself by teaching music and<br />

also completed his first important composition, Das klagende Lied.<br />

He accepted a succession of conducting posts in Kassel, Prague,<br />

Leipzig and Budapest; and the Hamburg State Theatre, where he<br />

served as First Conductor from 1891–97. For the next ten years,<br />

Mahler was Resident Conductor and then Director of the prestigious<br />

Vienna Hofoper.<br />

The demands of both opera conducting and administration<br />

meant that Mahler could only devote the summer months to<br />

composition. Working in the Austrian countryside he completed nine<br />

symphonies, richly Romantic in idiom, often monumental in scale and<br />

extraordinarily eclectic in their range of musical references and styles.<br />

He also composed a series of eloquent, often poignant songs, many<br />

themes from which were reworked in his symphonic scores.<br />

An anti-Semitic campaign against Mahler in the Viennese press<br />

threatened his position at the Hofoper, and in 1907 he accepted an<br />

invitation to become Principal Conductor of the Metropolitan Opera<br />

and later the New York Philharmonic. In 1911 he contracted a bacterial<br />

infection and returned to Vienna. When he died a few months<br />

before his 51st birthday, Mahler had just completed part of his Tenth<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> and was still working on sketches for other movements.<br />

Composer Profiles © Andrew Stewart<br />

8 Programme Notes Programme Notes 9

Valery Gergiev<br />

Conductor<br />

Principal Conductor of the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> since January 2007, Valery Gergiev<br />

performs regularly with the LSO at the<br />

Barbican, at the Proms and at the Edinburgh<br />

Festival, as well as regular tours of Europe,<br />

North America and Asia. During the 2010/11<br />

season he will lead them in appearances in<br />

Germany, France, Switzerland, Japan and<br />

the USA.<br />

Valery Gergiev is Artistic and General<br />

Director of the Mariinsky Theatre, founder<br />

and Artistic Director of the Stars of the<br />

White Nights Festival and New Horizons<br />

Festival in St Petersburg, the Moscow Easter<br />

Festival, the Gergiev Rotterdam Festival, the<br />

Mikkeli International Festival, and the Red<br />

Sea Festival in Eilat, Israel. He succeeded<br />

Sir Georg Solti as conductor of the World<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> for Peace in 1998 and leads them<br />

this season in concerts in Abu Dhabi.<br />

His inspired leadership of the Mariinsky<br />

Theatre since 1988 has taken the Mariinsky<br />

ensembles to 45 countries and has brought<br />

universal acclaim to this legendary institution,<br />

now in its 227th season. Having opened a<br />

new concert hall in St Petersburg in 2006,<br />

Maestro Gergiev looks forward to the opening<br />

of the new Mariinsky Opera House in the<br />

summer of 2012.<br />

Born in Moscow, Valery Gergiev studied<br />

conducting with Ilya Musin at the Leningrad<br />

Conservatory. Aged 24 he won the Herbert<br />

von Karajan Conductors’ Competition in<br />

Berlin and made his Mariinsky Opera debut<br />

one year later in 1978 conducting Prokofiev’s<br />

War and Peace. In 2003 he led St Petersburg’s<br />

300th anniversary celebrations, and opened<br />

the Carnegie Hall season with the Mariinsky<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, the first Russian conductor to do<br />

so since Tchaikovsky conducted the Hall’s<br />

inaugural concert in 1891.<br />

Now a regular figure in all the world’s major<br />

concert halls, he will lead the LSO and<br />

the Mariinsky <strong>Orchestra</strong> in a symphonic<br />

Centennial Mahler Cycle in New York in the<br />

2010/11 season. He has led several cycles in<br />

New York including Shostakovich, Stravinsky,<br />

Prokofiev, Berlioz and Richard Wagner’s Ring.<br />

He has also introduced audiences to several<br />

rarely-performed Russian operas.<br />

Valery Gergiev’s many awards include a<br />

Grammy, the Dmitri Shostakovich Award,<br />

the Golden Mask Award, People’s Artist of<br />

Russia Award, the World Economic Forum’s<br />

Crystal Award, Sweden’s Polar Music Prize,<br />

Netherlands’s Knight of the Order of the Dutch<br />

Lion, Japan’s Order of the Rising Sun, Valencia’s<br />

Silver Medal, the Herbert von Karajan prize and<br />

France’s Royal Order of the Legion of Honour.<br />

He has recorded exclusively for Decca<br />

(Universal Classics), and appears also on<br />

the Philips and Deutsche Grammophon<br />

labels. Currently recording for LSO Live, his<br />

releases include Mahler Symphonies Nos<br />

1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 8, Rachmaninov <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

No 2, Prokofiev Romeo and Juliet and<br />

Bartók Bluebeard’s Castle. His recordings<br />

on the newly formed Mariinsky Label are<br />

Shostakovich The Nose and Symphonies Nos<br />

1, 2, 11 & 15, Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture,<br />

Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 3 and<br />

Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Shchedrin<br />

The Enchanted Wanderer, Stravinsky Les<br />

Noces and Oedipus Rex, many of which<br />

have won awards including four Grammy<br />

nominations. The most recent release is<br />

Wagner Parsifal (<strong>September</strong> 2010), featuring<br />

René Pape and Gary Lehman.<br />

Valery Gergiev conducts<br />

Fri 19 Nov 2010 7.30pm<br />

Rodion Shchedrin Piano Concerto No 4<br />

(‘Sharp Keys’) with Olli Mustonen piano<br />

Mahler <strong>Symphony</strong> No 1 (‘Titan’)<br />

Tue 18 & Sun 23 Jan 2011 7.30pm<br />

Shostakovich Violin Concerto No 2<br />

with Sergey Khachatryan violin<br />

Tchaikovsky <strong>Symphony</strong> No 1 (‘Winter<br />

Daydreams’)<br />

Wed 2 & Thu 3 Mar 2011 7.30pm<br />

Mahler <strong>Symphony</strong> No 9<br />

Tickets from £8<br />

lso.co.uk (£1.50 bkg fee per transaction)<br />

020 7638 8891 (£2.50 bkg fee per transaction)<br />

Andrew Marriner<br />

Clarinet<br />

Andrew Marriner became Principal Clarinet of the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> in 1986, following in the footsteps of the late Jack Brymer.<br />

During his orchestral career he has also maintained his place on the<br />

worldwide solo and chamber music platform.<br />

His musical career began at the age of seven when he was a boy<br />

chorister at King’s College, Cambridge. Joining the National Youth<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> in 1968 he studied briefly at Oxford University and then<br />

extensively in Hannover, Germany with Hans Deinzer.<br />

As a soloist he has performed in collaboration with Leonard Bernstein,<br />

Sir Colin Davis, Richard Hickox, Antonio Pappano, André Previn,<br />

Mstislav Rostropovich, Michael Tilson Thomas and his father,<br />

Sir Neville Marriner. He has given world premieres of concertos written<br />

for him by Robin Holloway, Dominic Muldowney and John Tavener. He<br />

performed with the renowned soprano Edita Gruberova<br />

at Wigmore Hall in 2008.<br />

Andrew has recorded the core solo and chamber clarinet repertoire<br />

with various record companies including Philips, EMI, Chandos and<br />

Collins Classics. His concerto appearances are regularly broadcast<br />

by the BBC. A second recording of the Mozart concerto was released<br />

in 2004.<br />

Andrew is visiting Professor at the Royal Academy of Music, and was<br />

awarded an Hon RAM in 1996.<br />

Rachel Gough<br />

Bassoon<br />

Rachel Gough has been Principal Bassoon of the LSO since 1999. For<br />

eight years prior to joining the LSO she was Co-Principal with the BBC<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> and a professor at the Royal Academy of Music.<br />

As a student Rachel read anthropology and music at King’s College,<br />

Cambridge, before gaining Countess of Munster and German<br />

government scholarships for postgraduate study at the Royal<br />

Academy of Music and at the Hannover Hochschule für Musik with<br />

Klaus Thunemann. During that time she was Principal Bassoon of the<br />

European Community Youth <strong>Orchestra</strong> and won the Gold Medal at the<br />

Royal Overseas League.<br />

Rachel has appeared as a soloist with Sir Colin Davis, Bernard Haitink,<br />

Sir Neville Marriner, Gianandrea Noseda and Gennady Rozhdestvensky,<br />

amongst others. She has recorded and played chamber music with<br />

the Melos Quartet, Paul Meyer, Emma Johnson and James Galway. She<br />

is a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music.<br />

Don’t miss Rachel and Andrew on BBC Radio 3<br />

Back in June, Andrew and Rachel gave recitals at LSO St Luke’s as<br />

part of our regular Radio 3 Lunchtime Concert series. If you<br />

missed out (or were there but want to re-live it!) you can tune in to<br />

BBC Radio 3 next month to hear the broadcasts.<br />

Wed 27 Oct 1pm: Rachel Gough & Susan Tomes play Saint-Saëns & Elgar<br />

Fri 29 Oct 1pm: Andrew Marriner & Olga Sitkovetsky play Schumann<br />

10 The Artists Valery Gergiev © Gautier Deblonde<br />

Andrew Marriner © Nina Large / Rachel Gough © Gautier Deblonde<br />

The Artists 11

Lord Mayor’s Appeal 2010<br />

About Pitch Perfect<br />

Pitch Perfect is the name of the Lord Mayor’s Appeal 2010, which is<br />

raising funds to support the charitable work of the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> and the Cricket Foundation. Through their educational<br />

<strong>programme</strong>s, LSO On Track and StreetChance, both organisations<br />

provide dynamic musical and cricketing opportunities to young<br />

people in their schools and communities in <strong>London</strong>’s most challenging<br />

boroughs. Having identified a shared ambition to enhance the lives<br />

of young people, the two organisations have joined forces under the<br />

banner of the Appeal to create Pitch Perfect.<br />

By providing opportunities to play and perform in teams and groups,<br />

Pitch Perfect will support thousands of young <strong>London</strong>ers to develop<br />

new skills and levels of aspiration, acquire confidence and selfesteem,<br />

learn to respect themselves and each other and – regardless<br />

of their ultimate prowess as cricketers or as musicians – discover<br />

their full potential as well-rounded and productive individuals, leaders<br />

and team-players. Proven tangible benefits of participation in cricket<br />

and music include:<br />

• Increased self-confidence<br />

• Improved academic performance<br />

• Enhanced general well-being<br />

• Calming effect on body and mind<br />

• Improved employment prospects<br />

• Improved social interactions<br />

• Reduced drug and crime rate<br />

Pitch Perfect is aiming to generate sufficient funds to enable 75,000<br />

young people to participate in StreetChance and LSO On Track<br />

activities across <strong>London</strong>.<br />

12 Lord Mayor’s Appeal<br />

Jubayed’s story<br />

Jubayed was a quiet boy, not engaging in the community and<br />

somewhat isolated due to language barriers. When the StreetChance<br />

<strong>programme</strong> rolled into Stepney Green, he was one of the first to<br />

sign up to the community session. Throughout the <strong>programme</strong><br />

Jubayed has blossomed into a well-rounded strong leader within his<br />

community who strives to make things happen for others. He is now<br />

highly respected among his peers due to his attitude, commitment<br />

and passion. He has not missed any StreetChance sessions and has<br />

even represented Bangladesh in national Twenty20 youth and senior<br />

grassroots competitions.<br />

How you can make a difference tonight<br />

We are grateful for all donations, no matter how great or small.<br />

You can donate here and now: you will find an envelope on<br />

your seat and collectors will be in the foyers during the interval<br />

and after the concert. You can also make online and postal<br />

donations – see below.<br />

Donate online<br />

www.thelordmayorsappeal.org<br />

Post a cheque<br />

Lord Mayor’s Appeal 2010<br />

LSO, Barbican, <strong>London</strong>, EC2Y 8DS<br />

(made payable to Pitch Perfect)<br />

Thank you!<br />

LSO On Track StreetChance<br />

LSO On Track is part of the LSO Discovery <strong>programme</strong>, focusing<br />

specifically on the ten East <strong>London</strong> boroughs of the Thames Gateway,<br />

including the <strong>London</strong> 2012 host boroughs. Launched in 2008,<br />

LSO On Track has already achieved great success, reaching over<br />

5,000 young people from a wide range of social, cultural and<br />

economic backgrounds. Through a <strong>programme</strong> of outreach,<br />

workshops, concerts and holiday courses, LSO On Track enables<br />

young, inexperienced musicians who wouldn’t otherwise have<br />

the opportunity to make music with members of the LSO.<br />

The <strong>programme</strong> also supports a young talent development<br />

<strong>programme</strong> and an extensive training <strong>programme</strong> for school teachers<br />

to help embed music in schools and provide long-term musical<br />

opportunities to East <strong>London</strong>’s young people.<br />

StreetChance is a special project of Chance to Shine, the Cricket<br />

Foundation’s charitable campaign to regenerate competitive cricket<br />

throughout the state education sector. Since 2005, Chance to Shine<br />

has introduced cricket to one million children in over 3,700 schools.<br />

Designed to bring the benefits of Chance to Shine to inner-city areas,<br />

StreetChance combines activities in schools with community-based<br />

sessions that employ a fast and furious version of the game called<br />

‘Street20’ that gives everyone the chance to bat, bowl and field.<br />

Currently working across ten <strong>London</strong> boroughs, and in areas<br />

specifically identified by the Metropolitan Police, StreetChance is<br />

engaging schools in those parts of <strong>London</strong> where young people are<br />

perceived to be at greatest risk from crime and under-achievement.<br />

Lord Mayor’s Appeal<br />

13

Lord Mayor’s Appeal<br />

Supporters On stage tonight<br />

We would like to say a special thank you to our Appeal Board:<br />

Donald Brydon Chairman<br />

Lord Aldington<br />

Abdul Bhanji<br />

Sir John Bond<br />

Ian Davis<br />

Dame Clara Furse<br />

Gay Huey Evans<br />

Nicolas Moreau<br />

Michael Overlander<br />

Air Commodore Rick Peacock-Edwards<br />

David Powell<br />

Sir Evelyn de Rothschild<br />

John Spurling OBE<br />

14 Lord Mayor’s Appeal<br />

We are very grateful for the generous support of the following<br />

organisations:<br />

Appeal Event Sponsors<br />

Accenture<br />

Aviva<br />

Bank of America<br />

Barclays Capital<br />

Barclays Wealth<br />

Canon<br />

Deutsche Bank<br />

Linklaters<br />

<strong>London</strong> Metal Exchange<br />

Marks & Spencer<br />

PricewaterhouseCoopers<br />

Xstrata<br />

Xchanging<br />

Appeal Event Supporters<br />

Allen & Overy<br />

Appeal Corporate Supporters<br />

Blackrock<br />

Credit Suisse<br />

Goldman Sachs<br />

HSBC<br />

ICAP<br />

Lloyds TSB<br />

<strong>London</strong> Stock Exchange<br />

Rio Tinto<br />

Slaughter and May<br />

Smiths<br />

The Baltic Exchange<br />

Trusts and Foundations<br />

The Bagri Foundation<br />

The City Bridge Trust<br />

The Lloyds Charities Trust<br />

The Vodafone Foundation<br />

The Bernard Sunley Charitable Foundation<br />

The DLA Piper Charitable Trust<br />

Sir John Cass’s Foundation<br />

First Violins<br />

Roman Simovic Leader<br />

Carmine Lauri<br />

Lennox Mackenzie<br />

Nicholas Wright<br />

Nigel Broadbent<br />

Ginette Decuyper<br />

Jörg Hammann<br />

Michael Humphrey<br />

Maxine Kwok-Adams<br />

Claire Parfitt<br />

Laurent Quenelle<br />

Colin Renwick<br />

Sylvain Vasseur<br />

Alain Petitclerc<br />

Hazel Mulligan<br />

Helen Paterson<br />

Second Violins<br />

David Alberman<br />

Thomas Norris<br />

Sarah Quinn<br />

Miya Ichinose<br />

Richard Blayden<br />

Belinda McFarlane<br />

Iwona Muszynska<br />

Philip Nolte<br />

Paul Robson<br />

Stephen Rowlinson<br />

David Worswick<br />

Caroline Frenkel<br />

Roisin Walters<br />

Oriana Kriszten<br />

Violas<br />

Paul Silverthorne<br />

Gillianne Haddow<br />

German Clavijo<br />

Lander Echevarria<br />

Richard Holttum<br />

Robert Turner<br />

Heather Wallington<br />

Jonathan Welch<br />

Martin Schaefer<br />

Michelle Bruil<br />

Caroline O’Neill<br />

Fiona Opie<br />

Cellos<br />

Rebecca Gilliver<br />

Alastair Blayden<br />

Jennifer Brown<br />

Mary Bergin<br />

Noel Bradshaw<br />

Daniel Gardner<br />

Hilary Jones<br />

Minat Lyons<br />

Amanda Truelove<br />

Penny Driver<br />

Double Basses<br />

Rinat Ibragimov<br />

Nicholas Worters<br />

Patrick Laurence<br />

Matthew Gibson<br />

Thomas Goodman<br />

Jani Pensola<br />

Nikita Naumov<br />

Ben Griffiths<br />

Flutes<br />

Gareth Davies<br />

Adam Walker<br />

Siobhan Grealy<br />

Piccolo<br />

Sharon Williams<br />

Oboes<br />

Emanuel Abbühl<br />

Joseph Sanders<br />

Fraser MacAulay<br />

Cor Anglais<br />

Christine Pendrill<br />

Clarinets<br />

Andrew Marriner<br />

Chris Richards<br />

Chi-Yu Mo<br />

Bass Clarinet<br />

Lorenzo Iosco<br />

Bassoons<br />

Rachel Gough<br />

Bernardo Verde<br />

Joost Bosdijk<br />

Contra Bassoon<br />

Dominic Morgan<br />

Horns<br />

Timothy Jones<br />

David Pyatt<br />

Angela Barnes<br />

Estefanía Beceiro Vazquez<br />

Jonathan Lipton<br />

Jeffrey Bryant<br />

Brendan Thomas<br />

Trumpets<br />

Philip Cobb<br />

Nicholas Betts<br />

Gerald Ruddock<br />

Nigel Gomm<br />

Robin Totterdell<br />

Trombones<br />

Dudley Bright<br />

Katy Jones<br />

James Maynard<br />

Bass Trombone<br />

Paul Milner<br />

Tuba<br />

Patrick Harrild<br />

Timpani<br />

Antoine Bedewi<br />

Percussion<br />

Neil Percy<br />

David Jackson<br />

Tom Edwards<br />

Sacha Johnson<br />

Harp<br />

Bryn Lewis<br />

Celeste/Piano<br />

John Alley<br />

LSO String<br />

Experience Scheme<br />

Established in 1992, the<br />

LSO String Experience<br />

Scheme enables young string<br />

players at the start of their<br />

professional careers to gain<br />

work experience by playing in<br />

rehearsals and concerts with<br />

the LSO. The scheme auditions<br />

students from the <strong>London</strong><br />

music conservatoires, and 20<br />

students per year are selected<br />

to participate. The musicians<br />

are treated as professional<br />

’extra’ players (additional to<br />

LSO members) and receive<br />

fees for their work in line with<br />

LSO section players. Students<br />

of wind, brass or percussion<br />

instruments who are in their<br />

final year or on a postgraduate<br />

course at one of the <strong>London</strong><br />

conservatoires can also<br />

benefit from training with LSO<br />

musicians in a similar scheme.<br />

The LSO String Experience<br />

Scheme is generously<br />

supported by the Musicians<br />

Benevolent Fund and Charles<br />

and Pascale Clark.<br />

List correct at time of<br />

going to press<br />

See page xv for <strong>London</strong><br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> members<br />

Editor<br />

Edward Appleyard<br />

edward.appleyard@lso.co.uk<br />

Print<br />

Cantate 020 7622 3401<br />

Advertising<br />

Cabbell Ltd 020 8971 8450<br />

The <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

15

Inbox<br />

Your thoughts and comments about recent performances<br />

I think this was my favourite<br />

concert this year, among many<br />

great concerts.<br />

After Feltsman’s barnstorming<br />

Rachmaninov 3, who’d have<br />

thought Poulenc’s Gloria could<br />

trump him? But it did. This was<br />

music-making of the highest<br />

order, Sally Matthews singing<br />

as if from another planet, the<br />

LSO picking out the wondrous<br />

lines of Poulenc’s music with<br />

Stravinskian precision, and the<br />

chorus in glorious sympathy with<br />

the spirit of the piece.<br />

A night to remember, a night to<br />

be glad to be alive and at the<br />

Barbican!<br />

16 Jun 2010, Xian Zhang, Vladimir<br />

Feltsman & Sally Matthews /<br />

Rachmaninov & Poulenc<br />

16 Inbox<br />

‘Barnstorming’<br />

Richard Kirby<br />

‘Sublime’<br />

Colin Bruce<br />

I travelled from Liverpool to<br />

<strong>London</strong> especially to see this<br />

concert and what an evening of<br />

sublime music it was. It was an<br />

absolute joy to listen to.<br />

I was not familiar with Haydn’s<br />

hugely underrated and underperformed<br />

work prior to hearing<br />

it at the Barbican. I was delighted<br />

by the superb performances of<br />

Sir Colin, the LSO and chorus,<br />

and the soloists. It was a special<br />

delight to listen to the glorious<br />

singing of the beautiful Swedish<br />

soprano, Miah Persson. I feel that<br />

she has a wonderful ability to<br />

bring sensitivity and emotional<br />

depth to her pieces, which she<br />

sang so superbly.<br />

27 Jun 2010, Sir Colin Davis,<br />

Miah Persson, Jeremy Ovenden,<br />

Andrew Foster-Williams &<br />

LSC / Haydn The Creation<br />

‘I brought my whole family’<br />

Roger Lawrence<br />

I brought my whole family<br />

(three generations, aged 12–75)<br />

to hear my favourite symphony<br />

as a 75th birthday bash. We all<br />

enjoyed the <strong>programme</strong>.<br />

We did feel that there was a<br />

tendency to hurry a bit, but<br />

conversely, I was particularly<br />

glad that the tempo of the 1st<br />

movement 3rd subject was<br />

really crisp and incisive. Also,<br />

the temptation to introduce<br />

pauses between sections was<br />

avoided, ensuring a real sense of<br />

continuity.<br />

Perhaps not the most magical<br />

performance, but memorable<br />

and much enjoyed.<br />

1 Jul 2010, Daniel Harding &<br />

Renaud Capuçon / Bruch &<br />

Bruckner<br />

Want to share your views?<br />

Email us at comment@lso.co.uk<br />

Let us know what you think.<br />

We’d love to hear more from you<br />

on all aspects of the LSO’s work.<br />

Please note that the LSO may edit your comments<br />

and not all emails will be published.<br />

From Facebook and Twitter...<br />

hi! I heard you on “radio<br />

classique” in France!!! I know<br />

NOTHING about music but I feel<br />

it with my heart! Enjoy your trip<br />

in China.<br />

Marie-annick Gazel Peltier<br />

Firebird was awesome! Andrew<br />

Marriner is a God!! Thanks<br />

for an amazing night<br />

Robert Whitethread<br />

Your brass section Are lords!! :)<br />

John Dickson<br />

MahlerMad #ff @londonsymphony<br />

the friendliest orchestra in the<br />

world.<br />

amcil @londonsymphony<br />

yay! I finally got to read the latest<br />

tourblog. Love reading what<br />

Gareth has to say!