The role of implicit attitudes towards food and ... - ResearchGate

The role of implicit attitudes towards food and ... - ResearchGate

The role of implicit attitudes towards food and ... - ResearchGate

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Abstract<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>role</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> physical<br />

activity in the treatment <strong>of</strong> youth obesity<br />

Mietje Craeynest a,c,d , Geert Crombez a,c,d , Benedicte Deforche b,c,d ,<br />

Ann Tanghe c,d , Ilse De Bourdeaudhuij b,c,d,⁎<br />

a Department <strong>of</strong> Experimental Clinical <strong>and</strong> Health Psychology, Ghent University Henri Dunantlaan 2, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium<br />

b Department <strong>of</strong> Movement <strong>and</strong> Sports Sciences, Ghent University, Watersportlaan 2, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium<br />

c MPC Zeepreventorium, Koninklijke baan 5, B-8420 De Haan, Belgium<br />

d Research Institute for Psychology <strong>and</strong> Health, <strong>The</strong> Netherl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

Received 11 September 2006; received in revised form 11 March 2007; accepted 16 March 2007<br />

This study investigated whether <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>and</strong> self-reported <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> exercise <strong>attitudes</strong> changed during a residential six month<br />

treatment period in youngsters with obesity (n=19). Moreover, it was examined whether this attitudinal change explained their<br />

decrease in overweight during the program <strong>and</strong> at a one year follow up. Two Extrinsic Affective Simon Tasks (EAST) were<br />

conducted to investigate <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> exercise <strong>and</strong> <strong>food</strong>, respectively. Self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> were assessed using a<br />

questionnaire. <strong>The</strong> results revealed that the obese youngsters lost weight during the treatment, that was not regained at follow up.<br />

Mean self-reported <strong>and</strong> <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>attitudes</strong> did not change markedly. Moreover, changes in self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> were not predictive<br />

for decrease in overweight during <strong>and</strong> after the treatment. In contrast, some small effects were found for the change in <strong>implicit</strong><br />

<strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> exercise. Several possible explanations are discussed.<br />

© 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.<br />

Keywords: Obesity; Implicit; Attitudes; EAST; Food; Physical activity<br />

1. Introduction<br />

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com<br />

Eating Behaviors 9 (2008) 41–51<br />

<strong>The</strong> increasing prevalence <strong>of</strong> childhood <strong>and</strong> adolescence overweight <strong>and</strong> obesity in Western society is a serious<br />

problem (Lissau et al., 2004). It is generally acknowledged that the causal factor next to genetic predispositions is an<br />

interplay <strong>of</strong> an unhealthy diet <strong>and</strong> a sedentary lifestyle (Morgan, Tan<strong>of</strong>sky-Kraff, Wilfley, & Yanovski, 2002).<br />

For youngsters with severe obesity, family-based cognitive behavioural interventions that focus on increasing physical<br />

activity <strong>and</strong> decreasing unhealthy diets are recommended (Braet, Tanghe, De Bode, Franckx, & Van Winckel, 2003). In<br />

general, these programs have promising results. Nevertheless, a lot <strong>of</strong> youngsters regain a considerable amount <strong>of</strong> their<br />

weight after treatment (e.g., Braet et al., 2003; Braet, Tanghe, Decaluwé, Moens, & Rosseel, 2004). <strong>The</strong>refore, longitudinal<br />

⁎ Corresponding author. Ghent University, Department <strong>of</strong> Movement <strong>and</strong> Sports Sciences, Watersportlaan 2, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium. Tel.: +32 9<br />

264 63 11; fax: +32 9 264 64 84.<br />

E-mail address: Ilse.debourdeaudhuij@UGent.be (I. De Bourdeaudhuij).<br />

1471-0153/$ - see front matter © 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.<br />

doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.03.002

42 M. Craeynest et al. / Eating Behaviors 9 (2008) 41–51<br />

research is necessary to investigate whether the underlying dynamics <strong>of</strong> the <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> physical activity behaviour are<br />

affected by the treatment, <strong>and</strong> to what extent their change is related to weight loss <strong>and</strong> weight regain.<br />

Several characteristics have been found to be important predictors <strong>of</strong> weight loss in obese youngsters following<br />

treatment, under which baseline degree <strong>of</strong> overweight <strong>and</strong> the child's age (Braet, 2006). Further, an amount <strong>of</strong> theories<br />

have dealt with possible explaining psychological determinants, such as the learning history <strong>of</strong> the child <strong>and</strong> a<br />

heightened responsiveness to <strong>food</strong> cues (for a review, see Braet, 2005). From a healthy psychology perspective,<br />

<strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> exercise have been put forward as crucial factors in the development <strong>and</strong> maintenance <strong>of</strong><br />

obesity (e.g., De Bourdeaudhuij et al., 2005; Dennison & Shepherd, 1995).<br />

In most studies, <strong>attitudes</strong> are asked directly, for instance using self-reports. Recently, however, it has been argued<br />

that their indirect assessment, by which cognitions are inferred from behaviour performance other than self-report,<br />

should have a better explanatory <strong>and</strong> predictive value because <strong>of</strong> two reasons (Greenwald et al., 2002). First, indirect<br />

measures should be more resistant for dem<strong>and</strong> characteristics that <strong>of</strong>ten affect self-reports (see Schwarz, 1999). Second,<br />

indirect measures are supposed to catch cognitive automatic associations that guide spontaneous behaviour, <strong>and</strong> that<br />

can not easily be tapped by self-reports. <strong>The</strong> outcome <strong>of</strong> the indirect assessment <strong>of</strong> these associations is <strong>of</strong>ten called<br />

<strong>implicit</strong> cognitions. Implicit <strong>attitudes</strong> then are the measure <strong>of</strong> automatic associations between an attitude object <strong>and</strong> a<br />

certain valence (Greenwald et al., 2002).<br />

In the last decades, several indirect response time based paradigms have been constructed to assess <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>attitudes</strong><br />

(for a review, see Fazio & Olson, 2003), amongst which the affective priming task (Fazio, Sanbonmatsu, Powell, &<br />

Kardes, 1986), the Implicit Association Task (IAT; Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998) <strong>and</strong> the Extrinsic<br />

Affective Simon Task (EAST; De Houwer, 2003). <strong>The</strong> core principle <strong>of</strong> these tasks is that <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>attitudes</strong> are inferred<br />

from the reaction time (<strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> errors) performance on a computer sorting task. More specifically, it is<br />

assumed that response latencies will be shorter (<strong>and</strong> less errors will be made) when participants have to use the same<br />

response bottom to sort stimuli that carry the same valence (congruent stimuli; e.g., names <strong>of</strong> insects <strong>and</strong> negative<br />

nouns vs. names <strong>of</strong> flowers <strong>and</strong> positive nouns), than when the same response bottom has to be pressed for stimuli with<br />

an opposite valence (incongruent stimuli; e.g., names <strong>of</strong> insects <strong>and</strong> positive nouns vs. names <strong>of</strong> flowers <strong>and</strong> negative<br />

nouns). Implicit <strong>attitudes</strong> are calculated then by comparing the performance on the congruent stimuli with the<br />

performance on the incongruent stimuli.<br />

Indirect measures have been applied in several domains <strong>of</strong> clinical <strong>and</strong> health psychology (for a review, see Fazio &<br />

Olson, 2003). As described elsewhere (Craeynest et al., 2005), we used the EAST in a cross-sectional study<br />

investigating <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> exercise <strong>attitudes</strong> in children <strong>and</strong> adolescents with obesity at the beginning <strong>of</strong> an<br />

intensive treatment. Our results revealed a borderline significant effect, indicating that youngsters with obesity<br />

<strong>implicit</strong>ly preferred both unhealthy <strong>and</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong>, whereas normal-weight controls evaluated them as neutral. No<br />

effects were found for physical activity.<br />

Longitudinal research investigating whether <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> physical activity cognitions in youth obesity change over<br />

a treatment period, <strong>and</strong> to what extent they are related to treatment success (i.e., weight loss or weight gain), is scarce. We<br />

only know <strong>of</strong> the study by Barton, Walker, Lambert, Gately, <strong>and</strong> Hill (2004) in which a sentence-completion questionnaire<br />

was used to investigate whether automatic exercise <strong>and</strong> <strong>food</strong> cognitions change over the course <strong>of</strong> a residential weight loss<br />

camp for adolescents with obesity. <strong>The</strong>y found a reduction in negative <strong>and</strong> an increase in positive thoughts about exercise,<br />

but not in those about eating. Further, cognitive change was largely accounted for by the reduction in weight.<br />

This manuscript describes a longitudinal study in which <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>and</strong> self-reported <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> exercise <strong>attitudes</strong> are<br />

assessed in youngsters with obesity during a six month inpatient treatment <strong>and</strong> at a one year follow up. Self-reported<br />

<strong>attitudes</strong> are assessed with a questionnaire; <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>attitudes</strong> are assessed with an EAST. Three main questions are<br />

addressed: First, do <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>and</strong> self-reported <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> exercise <strong>attitudes</strong> change during an inpatient treatment for obesity?<br />

Second, to what extent does a change in these <strong>attitudes</strong> explain the variance in weight change during treatment? And third,<br />

to what extent does a change in these <strong>attitudes</strong> explain the variance in weight loss or regain at follow up?<br />

2. Methods<br />

2.1. Participants<br />

Participants were thirty-eight obese children <strong>and</strong> adolescents at the beginning <strong>of</strong> their hospitalization in 2002–2003<br />

in a medical-paediatric centre (MPC) that is specialized in the treatment <strong>of</strong> youth obesity. Fourteen <strong>of</strong> them dropped out

during the therapy because <strong>of</strong> having reached their therapy goal (n =4) or because <strong>of</strong> suspension due to behavioural<br />

problems breaking the rules <strong>of</strong> the centre such as smoking (n=10). Five could not be contacted at follow up. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

youngsters did not differ from the rest <strong>of</strong> the group in terms <strong>of</strong> gender, χ 2 b1, <strong>and</strong> baseline overweight, tb1. Both<br />

groups differed in age, t(36) =2.12, p b.05: <strong>The</strong> mean age <strong>of</strong> the dropout group was higher (M=14.53, SD=2.37) than<br />

the mean age <strong>of</strong> the study group. Data were analyzed on this restricted group <strong>of</strong> nineteen youngsters, representing 50%<br />

<strong>of</strong> the original sample that was tested in Craeynest et al. (2005). According to Cole, Bellizzi, Flegal, <strong>and</strong> Dietz (2000),<br />

all <strong>of</strong> them could be categorized as severely obese (mean ABMI 1 = 163.86, SD=14.97; 7 boys; age M=12.79,<br />

SD=2.68; range 9–18 yo).<br />

2.2. Treatment program<br />

<strong>The</strong> treatment consisted <strong>of</strong> a maximum twelve-month multi-component inpatient program. <strong>The</strong> duration <strong>of</strong> the<br />

treatment depended on the individual therapy goal <strong>of</strong> each participant. Every week <strong>and</strong> half <strong>of</strong> the school holidays, the<br />

youngsters returned home. <strong>The</strong> program focused on attaining a healthy lifestyle by increasing physical activity <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>fering<br />

a healthy diet within a cognitive behavioural framework. For an extensive description <strong>of</strong> the program, we refer to Braet et<br />

al. (2003). In short, concerning physical activity, all children received an individual physical training program for 4 h a<br />

week, including swimming, biking <strong>and</strong> fitness. Before <strong>and</strong> after school they were stimulated to participate for at least 2 h a<br />

day in active games <strong>and</strong> lifestyle activities. During the weekends <strong>and</strong> the holidays they spent at home, they noted how<br />

much they were physical active, using a diary. Provided that a stringent calorie restriction is not recommended for<br />

youngsters that are still growing, the diet contained between 1500 <strong>and</strong> 1800 kcal/day. More specifically, it consisted <strong>of</strong><br />

three meals <strong>and</strong> three snacks per day. <strong>The</strong> consumption <strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t drinks, sweets <strong>and</strong> high-calorie <strong>food</strong> was strictly regulated,<br />

but not completely banned. Further, the psychological counselling consisted <strong>of</strong> a twelve-week cognitive behavioural<br />

treatment program in small groups, followed by weekly individual problem-solving-based booster sessions. In order to<br />

change their lifestyle, the youngsters were taught self-modulating skills, such as self-regulation (e.g., self-observation <strong>and</strong><br />

self-instruction), self-evaluation, <strong>and</strong> self-reward. Finally, the program also involved the parents. <strong>The</strong>ywereprovided<br />

information in how the lifestyle <strong>of</strong> their child could change within the family.<br />

2.3. Materials<br />

2.3.1. Extrinsic Affective Simon Task<br />

Participants conducted two EASTs: One task was related to physical activity, <strong>and</strong> one related to <strong>food</strong>. An EAST<br />

assessing <strong>attitudes</strong> consists <strong>of</strong> attribute stimuli (words carrying a clear valence) <strong>and</strong> target stimuli (stimuli <strong>of</strong> which the<br />

<strong>attitudes</strong> are assessed). Individually selected attractive <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> physical activity words were used for the attribute<br />

stimuli. In the physical activity EAST, targets were nine pre-selected words related to physical activity, divided into<br />

three categories: sedentary activities (e.g., watching television), moderate intense activities (e.g., swimming) <strong>and</strong> high<br />

intense activities (e.g., exercising). In the <strong>food</strong> EAST, targets were pre-selected words related to <strong>food</strong>, divided into two<br />

categories: unhealthy <strong>food</strong> (e.g., French fries) <strong>and</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong> (e.g., apple). All target stimuli words are presented in<br />

the Appendix. For a more extended description <strong>of</strong> the EASTs, we refer to Craeynest et al. (2005).<br />

2.3.2. Self-reports<br />

Participants had to rate the valence <strong>of</strong> the <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> physical activity target stimuli words <strong>of</strong> the EASTs on a 7-point<br />

rating scale, ranging from ‘dislike’ (−3) to ‘like’ (+3).<br />

2.4. Procedure<br />

M. Craeynest et al. / Eating Behaviors 9 (2008) 41–51<br />

This study was approved by the Ethical committee <strong>of</strong> Ghent University. To investigate their change over the<br />

treatment period, participants were tested three times: at baseline (during the first three weeks <strong>of</strong> the treatment; T1),<br />

1 <strong>The</strong> Body Mass Index (BMI; weight/height 2 ; kg/m 2 ) is accepted as a reliable <strong>and</strong> valid index <strong>of</strong> relative adiposity. However, as mean normal<br />

values <strong>of</strong> BMI vary substantially with age <strong>and</strong> values for individuals <strong>of</strong> different ages are difficult to compare, an adjusted BMI (ABMI) was used.<br />

ABMI was calculated using the formula (actual BMI/ideal BMI [50th percentile for same sex <strong>and</strong> age])×100 (Valverde, Patin, Oliveira, Lopez, &<br />

Vitolo, 1998). <strong>The</strong> 50th percentiles were derived from Flemish growth reference charts. An ABMI <strong>of</strong> 100% is considered ideal.<br />

43

44 M. Craeynest et al. / Eating Behaviors 9 (2008) 41–51<br />

six months later (T2), <strong>and</strong> at follow up one year after completing the program (T3). Concerning T2, the participants<br />

were not exactly tested at the end <strong>of</strong> their treatment, as this moment was different for each <strong>of</strong> them. Each time, height,<br />

weight, <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>and</strong> self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> were assessed. For practical reasons, the first measurement was completed<br />

at the Department <strong>of</strong> Moving <strong>and</strong> Sports Science <strong>of</strong> Ghent University, whereas the second measurement was completed<br />

in the residential setting. For the one year follow up, the children were invited to the residential setting for a general<br />

check-up. Sixteen youngsters <strong>of</strong> the test group showed up. <strong>The</strong> other three were tested at home.<br />

All children were tested individually. <strong>The</strong> order in which the two EASTs were administered, was counterbalanced.<br />

<strong>The</strong> questionnaire was completed after both EASTs were conducted. Each EAST consisted <strong>of</strong> three different blocks.<br />

Before each task, the participant provided words for physical activities or <strong>food</strong>s that he/she really (dis)liked. Next, in a<br />

first practice block, these individually selected attribute words appeared r<strong>and</strong>omly four times in a white colour on the<br />

screen. Participants were instructed to classify these words according to their valence as quickly <strong>and</strong> as accurately as<br />

possible, by pressing the m-(positive) or the q-(negative) key <strong>of</strong> an AZERTY keyboard, in order to learn an extrinsic<br />

association between a positive (negative) valence, <strong>and</strong> the left (right) key. In a second practice block, each target<br />

stimulus was presented in at least once in blue <strong>and</strong> once in green. In the <strong>food</strong> task 12 trials were presented, <strong>and</strong> in the<br />

activity task 24 trials. Half <strong>of</strong> the participants pressed the m-key in response to green words <strong>and</strong> the q-key in response to<br />

blue words; the others pressed the m-key in response to blue words <strong>and</strong> the q-key in response to green words. In this<br />

way, they learned an association between a key carrying a valence <strong>and</strong> a colour. Finally, each task consisted <strong>of</strong> four<br />

crucial test blocks in which a mix <strong>of</strong> target <strong>and</strong> attribute words were presented. <strong>The</strong> physical activity task contained four<br />

test blocks <strong>of</strong> 32 trials (14 white trials, 18 coloured trials) each; the <strong>food</strong> task contained four test blocks <strong>of</strong> 38 trials each<br />

(14 white trials <strong>and</strong> 24 coloured trials). <strong>The</strong> words had to be classified depending on valence (for white words) or colour<br />

(for green <strong>and</strong> blue words). Stimuli were always presented in a r<strong>and</strong>om order, whereby the mixed blocks did not<br />

necessarily alternate between target (coloured) <strong>and</strong> attribute (white) stimuli. <strong>The</strong> inter-trial interval was 400 ms. If the<br />

participant responded incorrectly, a red cross appeared for 400 ms on the screen <strong>and</strong> the next stimulus was presented.<br />

2.5. Statistical analyses<br />

Analyses were carried out using SPSS 12.0 for Windows. <strong>The</strong> analyses <strong>of</strong> the EASTs took only the responses on the<br />

coloured test trials into account, whereby trials with an incorrect response were discarded (De Houwer, 2003). In line<br />

with Greenwald et al. (1998), reaction times (RTs) below 300 ms or above 3000 ms were recoded to 300 ms <strong>and</strong><br />

3000 ms respectively. All RTs were log-transformed. Also mean percentage <strong>of</strong> errors (PE) were analysed. On the selfreports,<br />

<strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> sedentary activities, moderate intense physical activity (PA), high intense PA, unhealthy <strong>food</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong> were obtained by averaging the respective item scores. Evolutions in mean <strong>attitudes</strong> were calculated<br />

conducting Repeated Measures ANOVA's. <strong>The</strong> explaining variance <strong>of</strong> attitudinal changes during treatment for the<br />

decrease in overweight during treatment <strong>and</strong> at follow up was analyzed using covariate multiple regression analyses.<br />

3. Results<br />

3.1. Mean <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>and</strong> self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> at baseline<br />

A 3 (word category: sedentary activities vs. moderate intense PA vs. high intense PA)×2 (extrinsic response<br />

valence: positive vs. negative) Repeated Measures ANOVA on the baseline reaction times <strong>of</strong> the physical activity task<br />

showed no significant effects, all Fsb2.85. Also the same 3×2 Repeated Measures ANOVA conducted on the baseline<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> errors revealed no effects, all Fsb2.19. However, a 2 (word category: unhealthy vs. healthy <strong>food</strong>) ×2<br />

(extrinsic response valence: positive vs. negative) Repeated Measures ANOVA on the baseline reaction times <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>food</strong> task showed a significant main effect <strong>of</strong> valence, F(1, 18)=6.08, pb.05. This indicates that the participants were<br />

positive <strong>towards</strong> both healthy <strong>and</strong> unhealthy <strong>food</strong>, which was also found in the total group as described in Craeynest<br />

et al. (2005). No other effects were found, all Fsb1. Also the same 2 ×2 Repeated Measure ANOVA conducted on the<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> errors, revealed no effects, all Fsb2.49. A three-level within factor (word category: sedentary activities<br />

vs. moderate intense vs. high intense PA) Repeated Measures ANOVA on the self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> physical<br />

activity, showed a significant effect, F(2, 17)=5.54, pb.05. Post hoc paired sample t-tests showed that moderate<br />

intense PA was rated more positive than sedentary activities, t(18) =3.08, pb.01, <strong>and</strong> high intense PA, t(18) =2.61,<br />

pb.05. A two-level within factor (word category: unhealthy vs. healthy <strong>food</strong>) Repeated Measures ANOVA on the

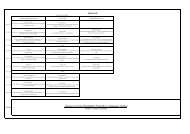

Table 1<br />

Mean <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ardized (SD) reaction times (RT) <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> errors (PE) on physical activity (PA) <strong>and</strong> <strong>food</strong> trials as a function <strong>of</strong> word category<br />

<strong>and</strong> extrinsic response valence, at baseline (T1), after six months (T2) <strong>and</strong> at a one year follow up (T3)<br />

T1 T2 T3<br />

RT PE RT PE RT PE<br />

M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD<br />

Physical activity (PA)<br />

Sedentary+pos 861 229 7.89 8.09 716 127 6.14 6.11 638 110 10.09 10.96<br />

Sedentary+neg 855 213 7.39 7.29 714 106 7.89 8.09 688 120 8.33 11.79<br />

Moderate intense PA+pos 880 272 7.02 8.46 743 224 8.77 15.33 706 135 10.09 16.80<br />

Moderate intense PA+neg 902 263 10.53 9.56 742 155 8.77 8.99 658 148 7.46 12.39<br />

High intense PA+pos 814 207 8.77 8.55 746 217 12.72 14.27 679 167 7.89 8.99<br />

High intense PA+neg<br />

Food<br />

833 179 6.58 8.60 736 160 7.46 13.86 676 134 7.46 16.87<br />

Unhealthy <strong>food</strong>+positive 843 255 8.96 8.37 737 172 9.65 7.49 685 105 8.33 8.33<br />

Unhealthy <strong>food</strong>+negative 893 277 7.67 9.35 717 178 8.77 8.20 686 86 8.11 9.57<br />

Healthy <strong>food</strong>+positive 841 261 7.67 8.85 707 168 9.65 9.11 687 150 7.02 7.49<br />

Healthy <strong>food</strong>+negative 898 277 9.91 8.00 734 173 9.43 6.49 717 97 8.55 11.49<br />

self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> <strong>food</strong>, showed a significant effect, F(1, 18)=4.47, pb.05. A post hoc paired t-test<br />

revealed that the participants were more positive <strong>towards</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong> than <strong>towards</strong> unhealthy <strong>food</strong>, t(18)=2.12,<br />

pb.05. Implicit associations are presented in Table 1; self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> are described in Table 2.<br />

Remarkably, the same Repeated Measures ANOVAs with the dropout participants vs. the remaining group included as<br />

between variable, revealed a significant main effect <strong>of</strong> group on the PA EAST, F(1, 36)=5.27, pb.05, <strong>and</strong> on the <strong>food</strong><br />

EAST, F(1, 36)=6.25, pb.05, showing that the dropout group in general reacted faster than the remaining group (PA task<br />

respectively M=783 ms, SD=44 ms <strong>and</strong> M=843 ms, SD=51 ms; <strong>food</strong> task respectively <strong>and</strong> M=790 ms, SD=37 ms <strong>and</strong><br />

M=831 ms, SD=44 ms), possibly due to the mean older age <strong>of</strong> the drop out group. Further, both groups did not differ on<br />

the self-report <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> PA, all Fsb1, however, an intriguing interaction effect was found between both groups<br />

<strong>and</strong> their self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> <strong>food</strong>, F(1, 36)=4.87, pb.05, indicating that at baseline the dropout group was<br />

more positive <strong>towards</strong> unhealthy <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> less positive <strong>towards</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong>, than the remaining group.<br />

3.2. Mean effect <strong>of</strong> the treatment on ABMI<br />

M. Craeynest et al. / Eating Behaviors 9 (2008) 41–51<br />

<strong>The</strong> mean total treatment time <strong>of</strong> the participants was almost eight months (M=7.89, SD=2.05). A Repeated<br />

Measures ANOVA with one three-level within factor (T1 vs. T2 vs. T3), showed a significant effect <strong>of</strong> time on ABMI,<br />

F(2, 17)=98.98, pb.001 (respectively T1: M=163.86, SD=14.97; T2: M=127.46, SD= 12.15; T3: M=130.21,<br />

SD= 16.43). Post hoc paired sample t-tests showed that the ABMI at baseline differed significantly from the ABMI at<br />

the end <strong>of</strong> the treatment, t(18) =13.50, pb.001, whereas the ABMI at the end <strong>of</strong> the treatment differed not from the<br />

ABMI at follow up, t(18)=1.07, ns. This indicated that the group <strong>of</strong> participants included in the present study became<br />

less overweight during the treatment, <strong>and</strong> that this decrease in overweight was maintained at follow up.<br />

Table 2<br />

Mean <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ardized (SD) self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> different kinds <strong>of</strong> physical activity <strong>and</strong> <strong>food</strong>, evaluated on a scale ranging from −3to+3,<br />

at baseline (T1), after six months (T2) <strong>and</strong> at a one year follow up (T3)<br />

T1 T2 T3<br />

M SD M SD M SD<br />

Physical activity (PA)<br />

Sedentary activities 1.34 0.99 1.70 0.97 2.00 0.54<br />

Moderate intense PA 2.04 1.06 2.07 1.01 2.16 0.80<br />

High intense PA<br />

Food<br />

1.02 1.09 1.67 1.02 1.88 0.80<br />

Unhealthy <strong>food</strong> 0.96 1.86 0.72 1.82 0.69 1.20<br />

Healthy <strong>food</strong> 2.07 0.80 1.89 0.97 1.91 1.24<br />

45

46 M. Craeynest et al. / Eating Behaviors 9 (2008) 41–51<br />

3.3. Mean evolution in <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>and</strong> self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> during treatment<br />

3.3.1. Implicit <strong>attitudes</strong><br />

Physical activity. A 3 (time: T1 vs. T2 vs. T3) ×3 (word category: sedentary activities vs. moderate intense PA vs.<br />

high intense PA) ×2 (extrinsic response valence: positive vs. negative) Repeated Measures ANOVA only revealed a<br />

main effect <strong>of</strong> time on the reaction times, F(2, 17)=10.22, pb.01, indicating that the participants reacted faster on the<br />

persecuting test moments (respectively T1: M=858 ms, SD=47 ms; T2: M=733 ms, SD=34 ms; T3: M=674 ms,<br />

SD=29 ms). No effects were found for word category, all Fsb1.82, <strong>and</strong> extrinsic response valence, all Fsb2.56. This<br />

indicated that the participants remained neutral <strong>towards</strong> sedentary activities, moderate <strong>and</strong> intense PA. <strong>The</strong> same<br />

3×3×2 ANOVA performed on the percentages <strong>of</strong> errors, showed no significant effects, all Fsb1.35.<br />

Food. Using a 3 (time: T1 vs. T2 vs. T3)×2 (word category: unhealthy vs. healthy <strong>food</strong>) ×2 (extrinsic response<br />

valence: positive vs. negative) Repeated Measures ANOVA, the results only revealed a main effect for time, F(2, 17)=<br />

416.88, pb.001. This indicated that the participants react faster on the persecuting test moments (respectively T1:<br />

M=868 ms, SD=59 ms; T2: M=724 ms, SD=38 ms; T3: M=694 ms, SD=23 ms). No effects were found for word<br />

category <strong>and</strong> extrinsic response valence, all Fsb3.23. <strong>The</strong> same 4×2×2 ANOVA was conducted on the percentages <strong>of</strong><br />

errors, however no significant effects were found, all Fsb2.10. Implicit <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> physical activity associations are<br />

presented in Table 1.<br />

3.3.2. Self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong><br />

Physical activity. A 3 (time: T1 vs. T2 vs. T3)×3 (word category: sedentary activities vs. moderate intense vs. high<br />

intense PA) Repeated Measures ANOVA showed a main effect <strong>of</strong> time, F(2, 17)=5.93, pb.05, indicating that the<br />

participants became more positive on the successive measure moments (T1: M=1.47, SD=0.14; T2: M=1.81,<br />

SD=0.14; T3: M=2.01, SD=0.11). Also the main effect <strong>of</strong> word category was significant, F(2, 17)=8.16, pb.01.<br />

Post hoc paired t-tests revealed that in general, moderate intense PA (M=2.09, SD=0.50) was rated more positive than<br />

sedentary activities (M=1.68, SD=0.40), t(18) =3.59, pb.01, <strong>and</strong> than high intense PA (M=1.52, SD=0.77), t(18) =<br />

2.78, p b.05. Sedentary activities <strong>and</strong> high intense PA were rated equally, tb1. <strong>The</strong> interaction effect <strong>of</strong> time <strong>and</strong> word<br />

category was not significant, Fb1.<br />

Food. A 3 (time: T1 vs. T2 vs. T3) ×2 (word category: unhealthy vs. healthy <strong>food</strong>) ANOVAwith Repeated Measures<br />

showed a main effect <strong>of</strong> word category, F(1, 17)=6.46, pb.05. A post hoc paired t-test revealed that, in general, the<br />

participants were more positive <strong>towards</strong> healthy (M=1.97, SD=0.69) than <strong>towards</strong> unhealthy <strong>food</strong> (M=0.91,<br />

SD=1.51), t(18)=2.38, pb.05. <strong>The</strong> main effect <strong>of</strong> time <strong>and</strong> the interaction effect <strong>of</strong> time <strong>and</strong> word category were not<br />

significant, both Fsb1. Table 2 describes the mean self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> for the persecuting test moments.<br />

3.4. Prediction <strong>of</strong> ABMI change during treatment by attitudinal change during treatment<br />

To investigate whether attitudinal changes could explain the variance in ABMI change, we conducted st<strong>and</strong>ard<br />

multiple regression analyses. Because <strong>of</strong> the small sample size, the predictive power <strong>of</strong> the several attitudinal change<br />

variables on ABMI change was examined separately for <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>and</strong> self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>and</strong> for <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> physical<br />

activity, resulting in four different models. In each model, baseline ABMI, age <strong>and</strong> sex (entered as a dummy variable:<br />

girl=0; boy=1) were entered as covariates. ABMI <strong>and</strong> attitudinal change during treatment were calculated by<br />

respectively subtracting the ABMI <strong>and</strong> attitudinal scores at T1 from T2.<br />

3.4.1. Implicit <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> physical activity<br />

In a first model, ABMI change during treatment was the dependent variable, <strong>and</strong> the change in attitude <strong>towards</strong><br />

sedentary activity (RT), <strong>towards</strong> moderate intense PA (RT), <strong>towards</strong> high intense PA (RT), <strong>towards</strong> sedentary activity<br />

(PE), <strong>towards</strong> moderate intense PA (PE), <strong>towards</strong> high intense PA (PE), baseline ABMI, age <strong>and</strong> sex were entered as<br />

independent variables. <strong>The</strong> model accounted for 73% <strong>of</strong> the variance, F(9, 18)=6.51, pb.01. Attitudinal change<br />

<strong>towards</strong> high intense PA (RT) was a significant predictor, adjusted for age, sex <strong>and</strong> baseline ABMI, β=.51; t(18) =2.91,<br />

pb.05. Remarkably, this indicated that a decrease in overweight was related to a more negative attitude <strong>towards</strong> high<br />

intense PA at the end <strong>of</strong> the treatment. Further, also baseline ABMI, β = −.57; t(18)=4.03, p b.01, <strong>and</strong> sex, β =.64;<br />

t(18)=4.12, p b.01, were significant predictors. <strong>The</strong> first indicated that decrease in overweight was related to a<br />

higher baseline ABMI, <strong>and</strong> the latter indicated that girls had a higher probability to decrease in overweight than

Table 3<br />

Regression analyses predicting AMBI change during treatment from <strong>implicit</strong> attitudinal change <strong>towards</strong> PA <strong>and</strong> <strong>food</strong> during treatment<br />

Adj.<br />

R 2<br />

boys. Age was a marginal significant predictor, β =.35; t(18)=2.14, p =.06, indicating that decrease in overweight<br />

was related to a younger age (see Table 3).<br />

3.4.2. Implicit <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> <strong>food</strong><br />

In a second model, ABMI change during treatment was the dependent variable, <strong>and</strong> the change in attitude <strong>towards</strong><br />

unhealthy <strong>food</strong> (RT), <strong>towards</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong> (RT), <strong>towards</strong> unhealthy <strong>food</strong> (PE), <strong>towards</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong> (PE), baseline<br />

ABMI, age <strong>and</strong> sex were entered as independent variables. <strong>The</strong> model accounted for 69% <strong>of</strong> the variance, F(7, 18)=<br />

6.75, pb.01. Attitudinal change <strong>towards</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong> (PE), was a significant predictor, β=.39; t(18)=2.49, pb.05,<br />

indicating that decrease in overweight was related to a more positive attitude <strong>towards</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong> at the end <strong>of</strong><br />

the treatment, adjusted for age, sex <strong>and</strong> baseline ABMI. Further, again baseline ABMI, β=−.62; t(18) =4.59, pb.01,<br />

<strong>and</strong> sex, β =.49; t(18)=3.62, p b.01, were significant predictors, <strong>and</strong> age was a marginal significant predictor,<br />

β =.30; t(18)=2.07, p =.06 (see Table 3).<br />

3.4.3. Self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> physical activity.<br />

In a third model, ABMI change during treatment was the dependent variable, <strong>and</strong> the change in attitude <strong>towards</strong><br />

sedentary activity, <strong>towards</strong> moderate intense PA, <strong>towards</strong> high intense PA, baseline ABMI, age <strong>and</strong> sex were entered as<br />

independent variables. <strong>The</strong> model accounted for 49% <strong>of</strong> the variance, F(6, 18)=3.88, pb.05. Only baseline ABMI<br />

<strong>and</strong> sex were significant predictors, respectively β=−.64; t(18) =3.06, pb.05 <strong>and</strong> β=.49; t(18) =2.65, pb.05 (see<br />

Table 4).<br />

Table 4<br />

Regression analyses predicting AMBI change during treatment from self-reported attitudinal change <strong>towards</strong> PA <strong>and</strong> <strong>food</strong> during treatment<br />

Adj.<br />

R 2<br />

Significant<br />

correlates<br />

M. Craeynest et al. / Eating Behaviors 9 (2008) 41–51<br />

Significant correlates St<strong>and</strong>ard coefficient<br />

beta<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ard coefficient<br />

beta<br />

Adj.<br />

R 2<br />

Significant<br />

correlates<br />

PA Food<br />

Total model: .49 Total model: .61<br />

F(6, 18)=3.88⁎ F(5, 18)= 6.73⁎⁎<br />

Sex .49⁎ Sex .53⁎⁎<br />

Age .21 Age .30<br />

Baseline ABMI −.64⁎ Baseline ABMI −.72⁎⁎<br />

Sedentary activity −.03 Unhealthy <strong>food</strong> .17<br />

Mod. intense PA .09 Healthy <strong>food</strong> .30<br />

High intense PA −.02<br />

⁎pb.05; ⁎⁎pb.01.<br />

Adj.<br />

R 2<br />

Significant<br />

correlates<br />

PA Food<br />

Total model: .73 Total model: .69<br />

F(9, 18)=6.51⁎⁎ F(7, 18)=6.75⁎⁎<br />

Sex .64⁎⁎ Sex .49⁎⁎<br />

Age .35 Age .30<br />

Baseline ABMI −.57⁎⁎ Baseline ABMI −.62⁎⁎<br />

Sedentary activity (RT) −.02 Unhealthy <strong>food</strong> (RT) −.14<br />

Mod. intense PA (RT) −.26 Healthy <strong>food</strong> (RT) −.03<br />

High intense PA (RT) .51⁎<br />

Sedentary activity (PE) .06 Unhealthy <strong>food</strong> (PE) −.01<br />

Mod. intense PA (PE) −.06 Healthy <strong>food</strong> (PE) .39⁎<br />

High intense PA (PE) .13<br />

⁎ pb.05; ⁎⁎ pb.01.<br />

47<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ard coefficient<br />

beta<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ard coefficient<br />

beta

48 M. Craeynest et al. / Eating Behaviors 9 (2008) 41–51<br />

Table 5<br />

Regression analyses predicting AMBI change at follow up from <strong>implicit</strong> attitudinal change <strong>towards</strong> PA <strong>and</strong> <strong>food</strong> during treatment<br />

Adj.<br />

R 2<br />

Significant<br />

correlates<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ard coefficient<br />

beta<br />

3.4.4. Self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> <strong>food</strong><br />

In a fourth model, ABMI change during treatment was the dependent variable, <strong>and</strong> the change in attitude <strong>towards</strong><br />

unhealthy <strong>food</strong>, <strong>towards</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong>, baseline ABMI, age <strong>and</strong> sex were entered as independent variables. <strong>The</strong> model<br />

accounted for 61% <strong>of</strong> the variance, F(5, 18)=6.73, pb.01. Only baseline ABMI <strong>and</strong> sex were significant predictors,<br />

respectively β=−.72; t(18) =4.44, pb.01 <strong>and</strong> β=.53; t(18) =3.35, pb.01 (see Table 4).<br />

3.5. Prediction <strong>of</strong> ABMI change at follow up by attitudinal change during treatment<br />

To investigate whether attitudinal changes could explain the variance in ABMI change at follow up, we conducted<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard multiple regression analyses in again four separate models. ABMI change at follow up was calculated by<br />

subtracting the ABMI at T2 from the ABMI at T3; attitudinal changes during treatment were calculated by subtracting<br />

the attitudinal scores at T1 from the attitudinal scores at T2.<br />

3.5.1. Implicit <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> physical activity<br />

In a first model, ABMI change at follow up was the dependent variable, <strong>and</strong> the change in attitude <strong>towards</strong> sedentary<br />

activity (RT), <strong>towards</strong> moderate intense PA (RT), <strong>towards</strong> high intense PA (RT), <strong>towards</strong> sedentary activity (PE),<br />

<strong>towards</strong> moderate intense PA (PE), <strong>towards</strong> high intense PA (PE), ABMI at the end <strong>of</strong> the treatment, age <strong>and</strong> sex were<br />

entered as independent variables. <strong>The</strong> model accounted for 40% <strong>of</strong> the variance, but was not significant, F(9, 18)=<br />

2.32 ns. Only the change in <strong>implicit</strong> attitude <strong>towards</strong> moderate PA (RT) was a significant predictor, β=.89;t(18) =2.78,<br />

pb.05, indicating that decrease in overweight at follow up is related to a change <strong>towards</strong> a negative <strong>implicit</strong> attitude<br />

<strong>towards</strong> moderate intense physical activity at the end <strong>of</strong> the treatment, adjusted for age, sex <strong>and</strong> ABMI (see Table 5).<br />

Adj.<br />

R 2<br />

Significant<br />

correlates<br />

PA Food<br />

Total model: .40 Total model .08<br />

F(9, 18)=2.32 F(7, 18)=1.22<br />

Sex −.34 Sex .29<br />

Age .37 Age .42<br />

Baseline ABMI .13 Baseline ABMI −.37<br />

Sedentary activity (RT) −.03 Unhealthy <strong>food</strong> (RT) .48<br />

Mod. intense PA (RT) .89⁎ Healthy <strong>food</strong> (RT) .02<br />

High intense PA (RT) .12<br />

Sedentary activity (PE) .15 Unhealthy <strong>food</strong> (PE) .23<br />

Mod. intense PA (PE) −.33 Healthy <strong>food</strong> (PE) .05<br />

High intense PA (PE) −.05<br />

⁎pb.05.<br />

Table 6<br />

Regression analyses predicting AMBI change at follow up from self-reported attitudinal change <strong>towards</strong> PA <strong>and</strong> <strong>food</strong> during treatment<br />

Adj.<br />

R 2<br />

Significant<br />

correlates<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ard coefficient<br />

beta<br />

Adj.<br />

R 2<br />

Significant<br />

correlates<br />

PA Food<br />

Total model: .03 Total model: .14<br />

F(6, 18)=1.10 F(5, 18)=0.57<br />

Sex .08 Sex .20<br />

Age .53 Age .43<br />

Baseline ABMI −.30 Baseline ABMI −.31<br />

Sedentary activity −.59 Unhealthy <strong>food</strong> −.13<br />

Mod. intense PA .53 Healthy <strong>food</strong> .28<br />

High intense PA .20<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ard coefficient<br />

beta<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ard coefficient<br />

beta

3.5.2. Implicit <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> <strong>food</strong><br />

In a second model, ABMI change at follow up was the dependent variable, <strong>and</strong> the change in attitude <strong>towards</strong><br />

unhealthy <strong>food</strong> (RT), <strong>towards</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong> (RT), <strong>towards</strong> unhealthy <strong>food</strong> (PE), <strong>towards</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong> (PE), ABMI at the<br />

end <strong>of</strong> the treatment, age <strong>and</strong> sex were entered as independent variables. <strong>The</strong> model accounted for only 8% <strong>of</strong> the<br />

variance, <strong>and</strong> was not significant, F(7, 18)=1.22 ns (see Table 5).<br />

3.5.3. Self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> physical activity<br />

In a third model, ABMI change at follow up was the dependent variable, <strong>and</strong> the change in attitude <strong>towards</strong><br />

sedentary activity, <strong>towards</strong> moderate intense PA, <strong>towards</strong> high intense PA, ABMI at the end <strong>of</strong> the treatment, age <strong>and</strong><br />

sex were entered as independent variables. <strong>The</strong> model accounted for only 3% <strong>of</strong> the variance, <strong>and</strong> was not significant, F<br />

(6, 18)=1.10 ns. (see Table 6).<br />

3.5.4. Self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> <strong>food</strong><br />

In a fourth model, ABMI change at follow up was the dependent variable, <strong>and</strong> the change in attitude <strong>towards</strong><br />

unhealthy <strong>food</strong>, <strong>towards</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong>, ABMI at the end <strong>of</strong> the treatment, age <strong>and</strong> sex were entered as independent<br />

variables. <strong>The</strong> model accounted for 14% <strong>of</strong> the variance, <strong>and</strong> was not significant, F(5, 18)b1 (see Table 6).<br />

4. Discussion<br />

M. Craeynest et al. / Eating Behaviors 9 (2008) 41–51<br />

This manuscript presented a longitudinal study, investigating whether <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>and</strong> self-reported <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

exercise <strong>attitudes</strong> changed during a six month inpatient treatment for youth obesity <strong>and</strong> at a one year follow up.<br />

Further, it was examined whether this change explained the variance in overweight change during treatment <strong>and</strong> at<br />

follow up.<br />

A first finding was that the youngsters lost weight during the treatment, that seemed not to be regained at follow up.<br />

This lack <strong>of</strong> weight regain is in contrast with what is <strong>of</strong>ten found (e.g., Braet et al., 2003, 2004). However, the finding <strong>of</strong><br />

the present study should be interpreted with caution, as it is based on a very restricted <strong>and</strong> selective sample. As the<br />

dropout youngsters reported at baseline that they liked more unhealthy <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> liked less healthy <strong>food</strong> than the<br />

remaining group, it can be assumed that especially the youngsters that regained weight after treatment, dropped out or<br />

could not be contacted at follow up. Another possibility may be that the participants further lost weight after the<br />

six months <strong>of</strong> treatment that was regained at follow up.<br />

<strong>The</strong> self-reports revealed more favourable <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> physical activity than <strong>towards</strong><br />

unhealthy <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> sedentary activities. This pattern was quite stable over time. Further, a change in self-reported<br />

<strong>attitudes</strong> was not related to decrease in overweight during treatment <strong>and</strong> at follow up. Possibly, dem<strong>and</strong><br />

characteristics leading to self-presentation strategies may have played a <strong>role</strong> (see Schwarz, 1999), but this pattern<br />

can also reflect a gap between a positive attitude <strong>towards</strong> health practices <strong>and</strong> the intention to effectively perform<br />

health behaviour. Moreover, it should be noted that the <strong>attitudes</strong> were assessed when the treatment had already<br />

started.<br />

Of particular interest was the change in <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> physical activity <strong>attitudes</strong> during treatment, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

relation with decrease in overweight. At baseline, the participants had positive <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> both healthy <strong>and</strong><br />

unhealthy<strong>food</strong>,whichwasals<strong>of</strong>oundinthetotalgroupsampleasdescribedinCraeynest et al. (2005).However,this<br />

mean effect disappeared in a longitudinal study design. Nevertheless, some specific changes in <strong>implicit</strong> attitude<br />

<strong>towards</strong> <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> physical activity seemed to be related to the decrease in overweight during treatment <strong>and</strong> at follow<br />

up. More specifically, it was found that the decrease in overweight at the end <strong>of</strong> the treatment was related to<br />

becoming more positive <strong>towards</strong> healthy <strong>food</strong> during therapy. This pattern seems in line with studies that applied the<br />

Transtheoretical Model <strong>of</strong> behavioural change (Prochaska & DiClimente, 1983) on fruit <strong>and</strong> vegetable consumption,<br />

which found that increasing the perception <strong>of</strong> the benefits <strong>of</strong> the consumption <strong>of</strong> fruit <strong>and</strong> vegetables is a crucial<br />

factor for the move <strong>towards</strong> a higher behavioural stage (e.g., Cullen, Bartholomew, Parcel, & Koehly, 1998; Greene<br />

et al., 2004). <strong>The</strong>refore, it may be assumed that emphasizing the benefits <strong>of</strong> healthy<strong>food</strong>iselementaryinthe<br />

treatment <strong>of</strong> childhood obesity. Further, a more negative attitude <strong>towards</strong> high intense physical activity <strong>and</strong> <strong>towards</strong><br />

moderate intense physical activity seemed to be predictive for respectively decrease in overweight at the end <strong>of</strong> the<br />

treatment <strong>and</strong> at follow up. At first sight, these effects are not in line with the expectations. Nevertheless, they can<br />

also indicate that the youngsters who lost much weight are fed up with being intensively physical active. However,<br />

49

50 M. Craeynest et al. / Eating Behaviors 9 (2008) 41–51<br />

given the fact that these effects were not found on both performance levels (reaction times <strong>and</strong> percentage <strong>of</strong> errors)<br />

<strong>and</strong> that earlier studies did not show any evidence for <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> physical activity (e.g., Craeynest<br />

et al., 2005; butseeBarton et al., 2004), the <strong>implicit</strong> attitude effects should be interpreted with caution. In contrast,<br />

decrease in overweight seemed to be strongly related to ‘fixed’ variables such as sex, age <strong>and</strong> baseline ABMI (see<br />

also Braet, 2006).<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are several aspects that may <strong>of</strong>fer a possible explanation for the only limited <strong>and</strong> tentative <strong>implicit</strong> attitude effects we<br />

found. First, it is obvious that the small sample size, due to the huge dropout, may have reduced the power <strong>of</strong> the analyses.<br />

Second, the treatment took place in a very controlled setting with strict diet <strong>and</strong> exercise guidelines. Given the<br />

accumulating evidence that the environment is an important predictor for <strong>food</strong> choice <strong>and</strong> physical activity (Booth<br />

et al., 2001), it may be that the decrease in overweight during treatment was rather due to ‘external’ environmental<br />

characteristics, than to ‘internalized’ psychosocial determinants such as <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>attitudes</strong>.<br />

Third, it has been demonstrated that <strong>implicit</strong> measures may not be considered as stable constructs that are<br />

immune for contextual influences (Blair, 2002). <strong>The</strong>refore, it may be that the results were attenuated by the different<br />

contexts in which the youngsters were assessed (at the medical paediatric centre, at the university, <strong>and</strong> for a minority<br />

at home).<br />

Fourth, as mentioned in the Introduction, there is no doubt that using indirect measures may have several advantages<br />

over self-reports (Greenwald et al., 2002). Nevertheless, each <strong>of</strong> the paradigms has its own limitations that should be<br />

considered. With respect to the EAST, at this moment little is known about its validity <strong>and</strong> reliability. Huijding <strong>and</strong> de<br />

Jong (2005) found that a pictorial version <strong>of</strong> the EAST had good predictive validity for avoidance behaviour in<br />

individuals with spider phobia. However, Teige, Schnabel, Banse, <strong>and</strong> Asendorpf (2004) found that the EAST<br />

investigating <strong>implicit</strong> self-concept <strong>of</strong> personality had low internal consistency. Undoubtedly, more research is needed<br />

about the psychometric characteristics <strong>of</strong> the EAST, not only in general, but also within specific domains such as in the<br />

assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> physical activity cognitions in children <strong>and</strong> adolescents. In addition, it should be investigated to<br />

what extent the performance on indirect measures in a longitudinal study design is related to learning effects. Steffens<br />

(2004) found that faking becomes easier after having some experience with an IAT, <strong>and</strong> probably the same is true for<br />

the EAST.<br />

Finally, there are some limitations that should be considered. First, the results <strong>of</strong> the treatment, both on decrease in<br />

overweight <strong>and</strong> on attitudinal change, would have been stronger if they could be compared with those <strong>of</strong> an untreated<br />

group <strong>of</strong> obese youngsters. Second, <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> exercise <strong>attitudes</strong> are not direct determinants <strong>of</strong> weight, but they are<br />

mediated by <strong>food</strong> intake <strong>and</strong> exercise behaviour. <strong>The</strong>refore, future research should include objective behavioural<br />

measures. Moreover, correlations between these behavioural <strong>and</strong> the <strong>implicit</strong> measures can provide then an idea <strong>of</strong> the<br />

validity <strong>of</strong> the <strong>implicit</strong> measures (see Teachman & Woody, 2003).<br />

In sum, this study showed that a decrease in overweight in obese youngsters after a six month inpatient treatment<br />

was not significantly related to self-reported <strong>attitudes</strong>. In contrast, a decrease in overweight seemed to be related to<br />

some changes in <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>attitudes</strong> <strong>towards</strong> <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> physical activity, but these findings should be interpreted with<br />

caution. More research is needed to the psychometric qualities <strong>of</strong> <strong>implicit</strong> measures within this field, <strong>and</strong> to what extent<br />

<strong>implicit</strong> <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong> exercise <strong>attitudes</strong> are related to actual <strong>food</strong> intake <strong>and</strong> exercise behaviour.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

This research was supported by grant B/03814/01 from the Ghent University. We are very grateful to the MPC<br />

Zeepreventorium <strong>and</strong> the children for their cooperation to this study. In addition, we wish to thank Jan De Houwer for<br />

his ideas on conceptualizing the experiment. Furthermore, many thanks go to all colleagues <strong>and</strong> students who assisted<br />

in data collection, especially Els Persijn, Leen Van Vlierberghe, Katrien Verhoeven <strong>and</strong> Mieke De Roo.<br />

Appendix A<br />

Target stimuli <strong>of</strong> the EAST<br />

Target stimuli <strong>food</strong>:<br />

Unhealthy <strong>food</strong> words: crisps, coke, French fries<br />

Healthy <strong>food</strong> words: water, apple, tomato

Target stimuli physical activity:<br />

Sedentary behaviour words: reading, watching TV, resting<br />

Moderate intense physical activity words: walking, cycling, swimming<br />

High intense physical activity words: running, training, exercising<br />

References<br />

M. Craeynest et al. / Eating Behaviors 9 (2008) 41–51<br />

Barton, S. B., Walker, L. L. M., Lambert, G., Gately, P. J., & Hill, A. J. (2004). Cognitive change in obese adolescent losing weight. Obesity<br />

Research, 12, 313−319.<br />

Blair, I. (2002). <strong>The</strong> malleability <strong>of</strong> automatic stereotypes <strong>and</strong> prejudice. Personality <strong>and</strong> Social Psychology Review, 6, 242−261.<br />

Booth, S. L., Sallis, J. F., Ritenbaugh, C., Hill, J. O., Birch, L. L., Frank, L. D., et al. (2001). Environmental <strong>and</strong> societal factors affect <strong>food</strong> choice <strong>and</strong><br />

physical activity: Rationale, influences, <strong>and</strong> leverage points. Nutrition Reviews, 59, S21−S39.<br />

Braet, C. (2005). Psychological pr<strong>of</strong>ile to become <strong>and</strong> to stay obese. International Journal <strong>of</strong> Obesity, 29, S19−S23.<br />

Braet, C. (2006). Patient characteristics as predictors <strong>of</strong> weight loss after an obesity treatment for children. Obesity Research, 14, 148−155.<br />

Braet, C., Tanghe, A., De Bode, P., Franckx, H., & Van Winckel, M. (2003). Inpatient treatment <strong>of</strong> obese children: A multicomponent programme<br />

without stringent calorie restriction. European Journal <strong>of</strong> Pediatrics, 162, 391−396.<br />

Braet, C., Tanghe, A., Decaluwé, V., Moens, E., & Rosseel, Y. (2004). Inpatient treatment for children with obesity: Weight loss, psychological wellbeing,<br />

<strong>and</strong> eating behaviour. Journal <strong>of</strong> Pediatric Psychology, 29, 519−529.<br />

Cole, T. J., Bellizzi, M. C., Flegal, K. M., & Dietz, W. H. (2000). Establishing a st<strong>and</strong>ard definition for child overweight <strong>and</strong> obesity worldwide:<br />

International survey. British Medical Journal, 320, 1−6.<br />

Craeynest, M., Crombez, G., De Houwer, J., Deforche, B., Tanghe, A., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2005). Explicit <strong>and</strong> <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>attitudes</strong> toward <strong>food</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

physical activity in childhood obesity. Behaviour Research <strong>and</strong> <strong>The</strong>rapy, 43, 1111−1120.<br />

Cullen, K. W., Bartholomew, L. K., Parcel, G. S., & Koehly, L. (1998). Measuring stages <strong>of</strong> change for fruit <strong>and</strong> vegetable consumption in 9- to 12year-old<br />

girls. Journal <strong>of</strong> Behavioral Medicine, 21, 241−254.<br />

De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Lefevere, J., Deforche, B., Wijndaele, K., Matton, L., & Philippaerts, R. (2005). Physical activity <strong>and</strong> psychosocial correlates in<br />

normal weight <strong>and</strong> overweight 11 to 19 year olds. Obesity Research, 13, 1097−1105.<br />

De Houwer, J. (2003). <strong>The</strong> Extrinsic Affective Simon Task. Experimental Psychology, 50, 77−85.<br />

Dennison, C. M., & Shepherd, R. (1995). Adolescent <strong>food</strong> choice: An application <strong>of</strong> the <strong>The</strong>ory <strong>of</strong> Planned Behaviour. Journal <strong>of</strong> Human Nutrition<br />

<strong>and</strong> Dietetics, 8, 9−23.<br />

Fazio, R. H., & Olson, M. A. (2003). Implicit measures in social cognition research: <strong>The</strong>ir meaning <strong>and</strong> use. Annual Review <strong>of</strong> Psychology, 54,<br />

297−327.<br />

Fazio, R. H., Sanbonmatsu, D. M., Powell, M. C., & Kardes, F. R. (1986). On the automatic activation <strong>of</strong> <strong>attitudes</strong>. Journal <strong>of</strong> Personality <strong>and</strong> Social<br />

Psychology, 50, 229−238.<br />

Greene, G. W., Fey-Yensan, N., Padula, C., Rossi, S., Rossi, J. S., & Clark, P. G. (2004). Differences in psychosocial variables by stage <strong>of</strong> change for<br />

fruit <strong>and</strong> vegetables in older adults. Journal <strong>of</strong> the American Dietetic Association, 104, 1236−1243.<br />

Greenwald, A. G., Banaji, M. R., Rudman, L. A., Farnham, S. D., Nosek, B. A., & Mellot, D. S. (2002). A unified theory <strong>of</strong> <strong>implicit</strong> <strong>attitudes</strong>,<br />

stereotypes, self-esteem, <strong>and</strong> self-concept. Psychological Review, 109, 3−25.<br />

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. (1998). Measuring individual differences in <strong>implicit</strong> cognition: <strong>The</strong> Implicit Association Test.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Personality <strong>and</strong> Social Psychology, 74, 1464−1480.<br />

Huijding, J., & de Jong, P. (2005). A pictorial version <strong>of</strong> the Extrinsic Affective Simon Task — Sensitivity to generally affective <strong>and</strong> phobia-relevant<br />

stimuli in high <strong>and</strong> low spider fearful individuals. Experimental Psychology, 52, 289−295.<br />

Lissau, I., Overpeck, M. D., Ruan, W. J., Due, P., Holstein, B. E., & Hediger, M. L. (2004). Body mass index <strong>and</strong> overweight in adolescents in 13<br />

European countries, Israel, <strong>and</strong> the United States. Archives <strong>of</strong> Pediatrics <strong>and</strong> Adolescent Medicine, 158, 27−33.<br />

Morgan, C. M., Tan<strong>of</strong>sky-Kraff, M., Wilfley, D. E., & Yanovski, J. A. (2002). Childhood obesity. Child <strong>and</strong> Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics <strong>of</strong> North<br />

America, 11, 257+.<br />

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClimente, C. C. (1983). Stages <strong>and</strong> processes <strong>of</strong> self-change <strong>of</strong> smoking: Toward an integrative model <strong>of</strong> change. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Consulting <strong>and</strong> Clinical Psychology, 51, 390−395.<br />

Schwarz, N. (1999). Self-reports. How the questions shape the answers. American Psychologist, 54, 93−105.<br />

Steffens, M. C. (2004). Is the Implicit Association Test immune for faking? Experimental Psychology, 51, 165−179.<br />

Teachman, B. A., & Woody, S. R. (2003). Automatic processing in spider phobia: Implicit fear associations over the course <strong>of</strong> treatment. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Abnormal Psychology, 112, 100−109.<br />

Teige, S., Schnabel, K., Banse, R., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2004). Assessment <strong>of</strong> multiple <strong>implicit</strong> self-concept dimensions using the Extrinsic Affective<br />

Simon Task (EAST). European Journal <strong>of</strong> Personality, 18, 495−520.<br />

Valverde, M. A., Patin, R. V., Oliveira, F. L. C., Lopez, F. A., & Vitolo, M. R. (1998). Outcomes <strong>of</strong> obese children <strong>and</strong> adolescents enrolled in a<br />

multidisciplinary health program. International Journal <strong>of</strong> Obesity, 22, 513−519.<br />

51