THE DILATED URETER - OU Medicine

THE DILATED URETER - OU Medicine

THE DILATED URETER - OU Medicine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>DILATED</strong> <strong>URETER</strong><br />

FREE CME ONLINE<br />

FREE CME ONLINE<br />

To earn CME credit for this activity, participants should read<br />

the article and log onto www.contemporaryurology.com,<br />

where they must pass a post-test. After completing the test<br />

and online evaluation, a CME letter will be emailed to them.<br />

The release date for this activity is June 1, 2006. The<br />

expiration date is June 1, 2007.<br />

Accreditation<br />

This activity has been planned and implemented in<br />

accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the<br />

Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education<br />

(ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of Thomson<br />

American Health Consultants (AHC) and Contemporary<br />

Urology. AHC is accredited by the ACCME to provide<br />

continuing medical education for physicians.<br />

AHC designates this educational activity for a maximum<br />

of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s). Physicians should<br />

only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their<br />

participation in the activity.<br />

Target audience<br />

This activity is designated for urologists.<br />

Educational objectives<br />

After completing the following CME activity, the reader<br />

should be able to:<br />

• Outline the basic embryologic development of the ureter.<br />

• Classify the adult and pediatric patient with a megaureter<br />

based on the etiology of the condition.<br />

• Utilize imaging and clinical signs and symptoms to<br />

identify patients with primary obsructed megaureter who<br />

may be candidates for surveillance.<br />

• List 3 indications that should prompt consideration of<br />

repair of the primary obstructed megaureter.<br />

Faculty disclosures<br />

The authors (Stephen D. Confer, MD, Dominic Frimberger,<br />

MD, and Bradley P. Kropp, MD), reviewers of CME content<br />

(Culley C. Carson, MD and Stephen E. Strup, MD) and staff<br />

editors (Nancy Lucas, Editor and Beverly Lucas, Senior<br />

Editor) report no relationships with companies having ties to<br />

this field of study.<br />

44 CONTEMPORARY UROLOGY JUNE 2006<br />

By Stephen D. Confer, MD, Dominic Frimberger, MD, and Bradley P. Kropp, MD<br />

While dilated ureters are usually identified<br />

in adults when they present with symptomatic<br />

complaints, in children, identification<br />

is most likely due to aggressive screening<br />

with perinatal ultrasonography (US). Urologists who primarily<br />

treat adults should be familiar with the principles of evaluation<br />

and management options for adult, pediatric, and fetal populations<br />

as they may be asked to consult on a newborn or fetus with<br />

a dilated ureter. See “Embryology,” page 45, for a brief review of<br />

ureteral development.<br />

A variety of terms have been applied to ureters of abnormal<br />

caliber, including megaloureter, megaureter, dilatation of the<br />

ureter, and widened ureter. King has suggested the term megaureter<br />

to describe any ureter that is found to be dilated. 1 This<br />

broad term is defined further by 3 etiologic categories: obstructed<br />

megaureter, refluxing megaureter, and nonrefluxing nonobstructed<br />

megaureter (Table 1). Each category is further classified into<br />

primary and secondary subgroupings. This article focuses on diagnosis<br />

and management of primary obstructed megaureter.<br />

ETIOLOGY AND PRESENTATION<br />

Primary obstructed megaureter occurs in both pediatric and<br />

adult populations. 2 Rather than being caused by a lumenal obstruction,<br />

the condition is due to an intrinsic abnormality or an<br />

adynamic segment of the distal ureter that leads to a functional<br />

obstruction. In the past, the functional obstruction was thought<br />

to be similar to that seen in Hirschsprung’s disease of the colon.<br />

However, this has been disproven as excised samples demonstrated<br />

the presence of neural plexuses. 3,4<br />

Approximately two thirds of reported patients are males;<br />

however, 1 series displayed a female predominance. 5 The abnormality<br />

is unilateral in approximately two thirds of cases. 5 The<br />

Dr. Confer is a Resident in Urology; Dr. Frimberger is Assistant<br />

Professor, Section of Pediatric Urology; and Dr. Kropp is Professor<br />

and Chief of Pediatric Urology, Section of Urology, and Vice<br />

Chairman of the Department of Urology; University of Oklahoma<br />

Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City.

WHAT EVERY UROLOGIST SH<strong>OU</strong>LD KNOW<br />

The most important aspect in the management of the dilated ureter in adults and<br />

children is identification of patients who will need and benefit from surgical repair.<br />

presence of other anomalies, such as contralateral ureteropelvic<br />

junction (UPJ) obstruction, renal agenesis or ectopia, and<br />

ureteral duplication associated with primary obstructed megaureters,<br />

may be seen in up to 40% of affected patients. 5<br />

In adults, primary obstructed megaureter is usually detected<br />

when patients present with pain or other symptoms from urinary<br />

tract infection (UTI), calculi, or decreased renal function. 2<br />

In mild cases, however, patients are typically asymptomatic, and<br />

the condition is found during an unrelated workup.<br />

In the pediatric population, routine perinatal US has dramatically<br />

increased the likelihood of detection of the dilated<br />

ureter. 6 The megaureter can be dilated up to 3 cm and thus is<br />

easily identified on US as a hypoechoic cystic-appearing mass in<br />

the retroperitoneum that may extend from the UPJ to the<br />

ureterovesical junction (UVJ). 7 In a 5-year series in which US<br />

was performed on 3,856 fetuses after 28 weeks of gestation, the<br />

prevalence of primary megaureter at the level of the UVJ was<br />

approximately 1 in 2,000. 8<br />

GRADING<br />

Several different grading systems have been promulgated, but<br />

none is useful in predicting which patients will require surgery<br />

and which will benefit from observation. The earliest classification<br />

system, devised in 1978 by Pfister and Hendren, categorizes<br />

Embryology<br />

T<br />

he development of the ureter begins around the fifth<br />

week of gestation. A diverticulum arises from the<br />

posteriomedial aspect of the lower portion of the bilateral<br />

mesonephric ducts. It then elongates posteriorly to meet the<br />

metanephric blastema, thus inducing nephrogenesis. The tip<br />

of the ureteric bud dilates to form the collecting system from<br />

the ureterovesical junction (UVJ ) to the level of the<br />

collecting duct. During the sixth through the ninth weeks,<br />

the embryonic kidney ascends from its pelvic position.<br />

During the ascent of the kidneys, the ureters elongate.<br />

The lumen of the forming ureter develops from the<br />

midureter cranially and caudally until the eighth week.<br />

The urogenital sinus remains separated from the ureteric<br />

UROlogic<br />

➤ Primary obstructed megaureter is<br />

caused by an intrinsic abnormality<br />

or an adynamic segment of the<br />

distal ureter that leads to a<br />

functional obstruction.<br />

➤ While adults typically present with<br />

hematuria or symptomatic<br />

complaints from UTI or stone<br />

disease, most cases in children are<br />

detected antenatally.<br />

lumen by a membrane. This membrane, known as the<br />

Chwalle’s membrane, disappears by the middle of<br />

the eighth week. At approximately the ninth week of<br />

gestation, muscularization is induced by the passing of<br />

the first excreted urine. At 18 weeks, normal physiologic<br />

narrowing can be discerned at the ureteropelvic junction<br />

(UPJ) and the UVJ. It is at this time that dilation of the<br />

ureter may be observed. After 19 weeks, the ureter<br />

continues to grow; however, the normal ureteral<br />

diameter in the fetal population rarely exceeds 5 mm. 1<br />

REFERENCE<br />

1. Cussen LJ. The morphology of congenital dilatation of the ureter: intrinsic lesions.<br />

Aust NZ J Surg. 1971;441:185-194.<br />

JUNE 2006 CONTEMPORARY UROLOGY 45

PRIMARY OBSTRUCTED MEGA<strong>URETER</strong><br />

TABLE 1<br />

Differential diagnosis of megaureter<br />

OBSTRUCTED MEGA<strong>URETER</strong><br />

Primary: This condition is due to an intrinsic abnormality or an adynamic<br />

segment of the distal ureter that leads to a functional obstruction.<br />

Secondary: Any cause of ureteral obstruction not due to an adynamic<br />

segment. Etiologies include congenital lesions (ureteropelvic junction<br />

obstruction, ectopic ureterocele), inflammatory conditions (tuberculosis,<br />

schistosomiasis, Crohn’s disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, pelvic<br />

abscess), trauma, tumors, lower urinary tract conditions, neurogenic<br />

bladder, benign prostatic hypertrophy, pelvic lipomatosis, and urethral<br />

obstruction.<br />

REFLUXING MEGA<strong>URETER</strong><br />

Primary: This condition occurs most often in children and describes a wide<br />

ureter secondary to vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), when an abnormality of<br />

the ureteral orifice (or tunnel length) is the cause of the reflux.<br />

Secondary: Reflux due to high bladder pressures from a neurogenic<br />

bladder or bladder outlet obstruction.<br />

NONREFLUXING, NONOBSTRUCTED MEGA<strong>URETER</strong><br />

Primary: Dilation not due to obstruction or reflux (prune-belly syndrome.)<br />

Secondary: In this condition, ureters remain dilated after the correction of<br />

initial pathology.<br />

primary obstructive megaureter in children and adults<br />

according to the degree of dilatation of the proximal<br />

ureter. 5 In grade 1, the dilatation is limited to the distal<br />

ureteral segment. In grade 2, the dilation extends into<br />

the proximal ureter and there may be mild caliectasis.<br />

In grade 3, the entire ureter is dilated proximal to the<br />

adynamic segment and there is moderate to severe<br />

caliectasis. One drawback to Pfister and Hendren’s<br />

grading system is that excretory urography, which is<br />

rarely necessary today, is required.<br />

The most commonly used classification for neonates,<br />

which is now standard<br />

in adults, was<br />

UROlogic<br />

➤ While US is highly sensitive in<br />

detecting dilated ureters, it lacks<br />

specificity for diseases that require<br />

intervention. We recommend US<br />

and VCUG within 48 hours of birth<br />

in antenatally diagnosed infants.<br />

46 CONTEMPORARY UROLOGY JUNE 2006<br />

devised by the Society<br />

for Fetal Urology<br />

(SFU). It assigns a<br />

grade from 0 to 4<br />

based on the degree<br />

of upper urinary tract<br />

dilation. In grade 0,<br />

the central renal complex<br />

is intact. In grade<br />

1, there is mild split-<br />

ting of the renal complex. In grade 2,<br />

the pelvis is dilated but the calyces are<br />

not dilated. In grade 3, the pelvis is<br />

markedly split and the calyces are uniformly<br />

dilated but the renal parenchyma<br />

is normal. Grade 4 shares the characteristics<br />

of grade 3, but there is thinning<br />

of the renal parenchyma.<br />

EVALUATION OF PRENATALLY<br />

DIAGNOSED MEGA<strong>URETER</strong><br />

While US is highly sensitive for the detection<br />

of a dilated ureter, it lacks specificity<br />

for diseases that will actually require<br />

intervention. Classification of<br />

megaureters based on the etiology of<br />

the dilation allows the clinician to better<br />

inform patients about the treatment options<br />

and their risks and benefits. Thus,<br />

at our institution, we recommend that<br />

newborns with prenatally diagnosed<br />

megaureters undergo US and voiding<br />

cystourethrography (VCUG) within 48<br />

hours of birth. If reflux is ruled out on<br />

VCUG, we proceed to DTPA diuresis<br />

renography to better evaluate renal<br />

function and to determine the degree of<br />

ureteral obstruction (Figure 1).<br />

MANAGEMENT IN ADULTS<br />

Adults with primary obstructed megaureter typically<br />

present with pain, infection, or hematuria. Radiologic<br />

evaluation (Figure 1) usually reveals pathology in the<br />

distal ureter. Therefore, aggressive surgical management<br />

has been recommended for adults.<br />

Hemal and colleagues identified 53 of 55 adult primary<br />

obstructed megaureters on the basis of studies obtained<br />

to evaluate symptoms. 2 While the authors advocated<br />

surgical management in most instances, they<br />

found it unrewarding in patients with bilateral disease<br />

who have advanced renal failure. Of 5 patients with bilateral<br />

primary obstructed megaureter and uremia, 3<br />

underwent ureteral reimplantation. Of that group, only<br />

1 improved with adequate drainage, and the other 2 patients<br />

died. 2<br />

MANAGEMENT IN CHILDREN<br />

While surgery is the first-line therapy for primary obstructed<br />

megaureter in adults, the approach in children<br />

is evolving. Several studies have compared surgical<br />

outcomes with conservative management, but all are<br />

retrospective and involve a considerable selection

ias. 7,9,10 Nevertheless, these studies<br />

document a shift from the traditional<br />

approach of surgical management to<br />

the current trend of surveillance.<br />

Between 1981 and 1987, Keating<br />

and colleagues assessed 44 renal units<br />

in 35 neonates with primary obstructed<br />

megaureter. 7 Infants with ureters<br />

dilated down to the UVJ with varying<br />

degrees of hydronephrosis were included<br />

in the study. Infants with secondary<br />

obstructed megaureters were<br />

eliminated from the analysis. Antenatal<br />

diagnosis was made by US in 23 of<br />

44 units. Of the 23 units, 87% were<br />

managed nonoperatively. Diagnoses<br />

for the remaining 21 units were made<br />

on the basis of symptomatic complaints<br />

due to UTI or the presence of a<br />

flank mass, or they were incidentally<br />

discovered. Only 12 of the 21 symptomatic<br />

units were managed conservatively.<br />

Subsequently, surgery was performed<br />

on 2 of the 12 conservatively<br />

managed units because of increased<br />

obstruction on DTPA diuresis renogram<br />

and increased dilation on US.<br />

The authors suggested that a decision<br />

to manage asymptomatic patients<br />

conservatively should be based on an<br />

estimate of absolute renal function as<br />

determined by diuresis renography. 7<br />

In 1994, Baskin and associates 9<br />

provided a long-term follow up of Keating and colleagues’<br />

7 carefully selected group and found that 10 of<br />

the original 35 neonates with 44 renal units ultimately<br />

underwent surgery. The remaining 25 were observed<br />

and managed with serial urinary tract imaging using<br />

DTPA diuresis renography, intravenous pyelography<br />

(IVP), and/or renal US. Seventeen of the 25 were diagnosed<br />

antenatally, 2 were identified due to infection,<br />

and 6 incidentally diagnosed. Mean follow-up was 7.3<br />

years for 24 patients. One patient was lost to follow-up<br />

after 1.5 years. The conservatively managed patients<br />

demonstrated no decline of renal function on DTPA<br />

diuresis renography during the observation period.<br />

The authors concluded that conservatively managed<br />

patients should be monitored closely as indications for<br />

surgical repair may arise. 9<br />

McLellan and co-workers evaluated the records of<br />

54 newborns who were prenatally diagnosed with primary<br />

obstructed megaureter from 1993 to 1998. 10 Me-<br />

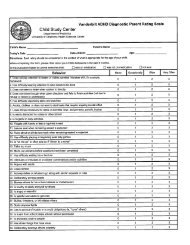

FIGURE 1<br />

Initial radiographic evaluation of suspected urologic<br />

abnormality<br />

Reflux<br />

Vesicoureteral<br />

reflux<br />

SUSPECTED UROLOGIC ABNORMALITY<br />

(prenatal US or symptoms)<br />

US shows dilation<br />

Perform VCUG<br />

Obstructed<br />

megaureter<br />

dian follow-up was 25.8 months. A total of 69 units<br />

were confirmed postnatally using various imaging<br />

modalities. Antibiotic prophylaxis was continued until<br />

the children were between the ages of 9 and 12 months,<br />

depending on physician’s preference. No child had a<br />

culture-documented UTI.<br />

Resolution, defined as a decrease in hydronephrosis to<br />

SFU grade 1 without hydroureter or minimal residual<br />

hydroureter, occurred in 39 (72%) patients. 10 Five patients<br />

(9%) had no resolution during the surveillance period,<br />

and 10 (19%)<br />

underwent surgery.<br />

The presenting grade<br />

of hydronephrosis appeared<br />

to be an important<br />

predictor of<br />

the resolution rate.<br />

SFU hydronephrosis<br />

grades 1 to 3 were<br />

No reflux<br />

Perform DTPA diuresis<br />

renography<br />

Obstruction No obstruction<br />

Nonobstructing,<br />

nonrefluxing<br />

megaureter<br />

UROlogic<br />

➤ Aggressive surgical management is<br />

recommended for most adults with<br />

primary obstructed megaureter.<br />

JUNE 2006 CONTEMPORARY UROLOGY 47

PRIMARY OBSTRUCTED MEGA<strong>URETER</strong><br />

“Parents of children with primary obstructed<br />

megaureter should be reassured that the<br />

condition is likely to resolve spontaneously.”<br />

more likely to resolve within 12 to 36 months. Increasing<br />

or severe hydronephrosis, decreasing renal function,<br />

and/or retrovesical ureteral diameter greater than 1 cm<br />

seemed to correlate with the need for surgical repair.<br />

Multiple reports support conservative management<br />

for primary obstructed megaureter detected in asymptomatic<br />

neonates. 6,7,9,10 We follow these patients with<br />

serial US and DTPA diuresis renography if increased<br />

dilation is observed on US (Figure 2). Once vesicoureteral<br />

reflux has been excluded by VCUG, antibiotic<br />

prophylaxis can be discontinued.<br />

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY<br />

The absolute indications for surgical intervention have<br />

yet to be determined. Indications for surgery suggested<br />

by Simoni and associates include significant impairment<br />

of urine flow on renal scan, worsening renal<br />

function during observation, and recurrent UTI in<br />

spite of adequate antibiotic prophylaxis. 11<br />

Stehr and colleagues proposed 3 indications for<br />

surgery using US, VCUG, IVP, and MAG-3 renal scan:<br />

initial impaired renal function with an obstructive pattern,<br />

normal function and at least an equivocal urinary<br />

drainage pattern with no improvement, or deterioration<br />

of the urinary drainage and/or function during follow-up.<br />

Using these criteria, only 5 (9.6%) of 42 patients<br />

were managed surgically. 12<br />

Liu and co-workers studied 67 units with pathology<br />

at the UVJ. 13 Eleven<br />

(17%) patients failed<br />

UROlogic<br />

➤ In most antenatally diagnosed<br />

children, the condition resolves<br />

spontaneously. Consequently,<br />

asymptomatic patients can be<br />

followed conservatively with US.<br />

If dilation increases on US, DTPA<br />

diuresis renography should be<br />

performed.<br />

48 CONTEMPORARY UROLOGY JUNE 2006<br />

conservative therapy<br />

and required surgical<br />

repair—3 due to<br />

breakthrough infections<br />

and 8 because<br />

of deteriorating function.<br />

8 The remaining<br />

56 (83%) patients<br />

were managed conservatively<br />

by periodic<br />

followup with US<br />

and DTPA diuresis<br />

renography.<br />

SURGICAL METHODS OF REPAIR<br />

In uncomplicated nondilated ureters, reported success<br />

rates for the various open reimplantation techniques<br />

are well over 95% in children 1 year of age or<br />

older. 14 However, for large dilated ureters requiring<br />

plication or tapering in addition to the usual intravesical<br />

reimplant, no conclusive data have been published.<br />

Glassberg and associates reported a 99% success<br />

rate with tapering using a transverse ureteral advancement<br />

technique of ureteroneocystostomy (Cohen<br />

reimplant) in 7 primary obstructed megaureters. 14<br />

They noted that megaureters measuring 8 to 12 mm in<br />

width, regardless of etiology, can be reimplanted successfully<br />

without tapering.<br />

Hospitalization following reimplantation usually<br />

only requires an overnight stay. A double-pigtail<br />

ureteral stent is routinely placed and is removed at<br />

1 month. Ureteral reimplantation in the neonatal period<br />

can be difficult due to the discrepancy in size between<br />

the megaureter and the small neonatal bladder.<br />

Should surgery become necessary in the neonatal<br />

period, we recommend that a cutaneous ureterostomy<br />

be performed. This procedure is followed in the first<br />

year of life by open intravesical reimplantation with or<br />

without the tapering. The need for surgery is based on<br />

initial poor renal function tests, a 10% reduction in serial<br />

renal function tests, worsening serial US findings,<br />

and/or the presence of breakthrough infections.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

The most important aspect in the management of the<br />

dilated ureter is identification of patients who will need<br />

and benefit from surgical repair. Historically, patients<br />

with dilated ureters presented with symptomatic complaints,<br />

and diagnosis preceded surgical correction.<br />

Today, antenatal US screening identifies most cases in<br />

children. The antenatal diagnosis of a dilated ureter<br />

with or without hydronephrosis warrants postnatal<br />

confirmation by US and institution of antibiotic prophylaxis.<br />

Ominous signs include bilaterally dilated systems,<br />

anuria, maternal oligohydramnios, or poor renal<br />

function, and necessitate more aggressive evaluation<br />

within the first 48 hours of life.<br />

Most patients with primary obstructed megaureter<br />

detected antenatally can be followed conservatively<br />

with US. DTPA diuresis renography may be performed<br />

after identification of increased dilation on US. Following<br />

antenatal diagnosis of primary obstructed megaureter,<br />

72% resolve spontaneously, 19% will need operative<br />

repair, and 9% will have persistent dilation on<br />

imaging without symptoms or deterioration of func-

FIGURE 2<br />

Management of primary megaureter<br />

tion. 13 Predictors for the need for surgical management<br />

include severe or worsening hydronephrosis, ureteral<br />

dilation greater than 1 cm in diameter, and worsening<br />

renal function. 10<br />

While aggressive surgical management is usually<br />

recommended for adults with primary obstructed<br />

megaureter, parents of children with the condition<br />

should be reassured that it is likely to resolve spontaneously.<br />

However, surgical management, when indicated,<br />

is usually successful.<br />

CU<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Improvement or<br />

no change<br />

Perform serial US<br />

imaging<br />

Resolution of<br />

obstruction<br />

No further<br />

imaging<br />

1. King LR. Megaloureter: definition, diagnosis and management. J Urol.<br />

1980;123(2):222-223.<br />

2. Hemal AK, Ansari MS, Doddamani D, et al. Symptomatic and complicated<br />

adult and adolescent primary obstructive megaureter—indications for surgery:<br />

analysis, outcome, and follow-up. Urology. 2003;61(4):703-707.<br />

3. Dunnick NR, McCallum RW, Sandler CM. Textbook of Uroradiology. 1st<br />

ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1991.<br />

4. Leibowitz S, Bodian M. A study of the vesical ganglia in children and the<br />

relationship to the megaureter megacystis syndrome and Hirschsprung’s disease.<br />

J Clin Pathol. 1963;16:342-350.<br />

US, VCUG, and DTPA diuresis renography<br />

Primary megaureter<br />

Low- to mid-grade ureteral<br />

obstruction<br />

Worsening renal<br />

function<br />

Increased dilation<br />

DTPA diuresis<br />

renography<br />

Infection or pain<br />

High-grade ureteral<br />

obstruction<br />

Surgical repair<br />

Decreased function<br />

(>10%) or increased<br />

obstruction<br />

5. Pfister RC, Hendren WH. Primary megaureter in children and adults. Clinical<br />

and pathophysiologic features of 150 ureters. Urology. 1978;12(2):<br />

160-176.<br />

6. Manzoni C. Megaureter. Rays. 2002;27(2):83-85.<br />

7. Keating MA, Escala J, Snyder HM et al. Changing concepts in management<br />

of primary obstructive megaureter. J Urol. 1989;142(2 pt 2):636-640.<br />

8. Gunn TR, Mora JD, Pease P. Antenatal diagnosis of urinary tract abnormalities<br />

by ultrasonography after 28 weeks’ gestation: incidence and outcome.<br />

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(2 pt 1):479-486.<br />

9. Baskin LS, Zderic SA, Snyder HM, et al. Primary dilated megaureter: long<br />

term followup. J Urol. 1994;152(2 pt 2):618-621.<br />

10. McLellan DL, Retik AB, Bauer SB, et al. Rate and predictors of spontaneous<br />

resolution of prenatally diagnosed primary nonrefluxing megaureter.<br />

J Urol. 2002;168(5):2177-2180.<br />

11. Simoni F, Vino L, Pizzini C, et al. Megaureter: classification, pathophysiology,<br />

and management. Pediatr Med Chir. 2000;22(1):15-24.<br />

12. Stehr M, Metzger R, Schuster T, et al. Management of the primary obstructed<br />

megaureter (POM) and indications for operative treatment. Eur J Pediatr<br />

Surg. 2002;12(1):32-37.<br />

13. Liu HY, Dhillon HK, Yeung CK, et al. Clinical outcome and management<br />

of prenatally diagnosed primary megaureters. J Urol. 1994;152(2 pt 2):614-<br />

617.<br />

14. Glassberg KI, Laungani G, Wasnick RJ, et al. Transverse ureteral advancement<br />

technique of ureteroneocystostomy (Cohen reimplant) and a modification<br />

for difficult case (experience with 121 ureters). J Urol. 1985; 134(2):<br />

304-307.<br />

JUNE 2006 CONTEMPORARY UROLOGY 49