American Jewish Archives

American Jewish Archives

American Jewish Archives

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

In This Issue<br />

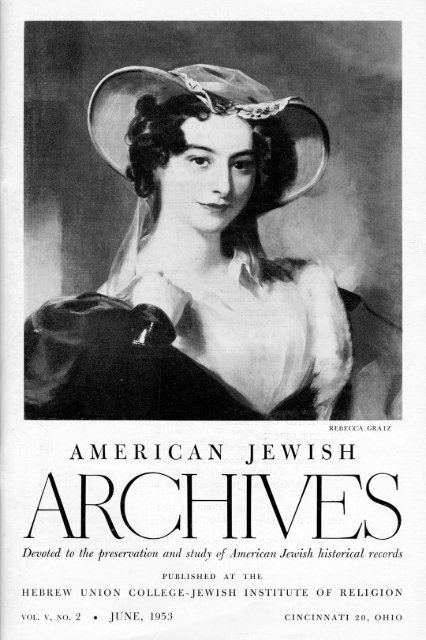

THE COVER:<br />

Portrait of Rebecca Gratz by Thomas Sully. The original is in the pos-<br />

session of the Henry Joseph family of Montreal.<br />

CRISIS AND REACTION: A STUDY IN JEWISH GROUP<br />

ATTITUDES (1929 - 1939). .......... .HENRY COHEN 'ji<br />

The reactions of major social groups within the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> community,<br />

during periods of crisis, are influenced by the role the particular<br />

group played in the <strong>American</strong> social and economic structure. The<br />

author illustrates his thesis by a study of <strong>American</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> social groups<br />

in the ~gso's, in relation to the Depression and to Hitlerian German<br />

anti-Semitism.<br />

REBECCA GRATZ ON RELIGIOUS BIGOTRY. ......... 114<br />

AMERICAN JEWRY IN 1753 AND IN 1853.. ......... 115<br />

LETTER TO THE EDITOR.. .......................... 120<br />

AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY<br />

AMERICAN RESPONSUM ..... .SOLOMON B. FREEHOF 121<br />

Manuel Josephson, <strong>American</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> communal leader and student of<br />

rabbinic lore, wrote a legal opinion in 1790 It touches on the use of the<br />

shofar ("ram's horn") and the question of permissibility to read the<br />

lesson of the week in the synagogue from a printed book.<br />

REVIEWS OF BOOKS:<br />

Albert M. Hyamson, THE SEPHARDIM OF<br />

ENGLAND, by JACOB R. MARCUS. ................. 126<br />

Simon Rawidowicz, editor, THE CHICAGO PINKAS,<br />

by LEONARD J. MERV~S.. .......................... I29<br />

Matthew Josephson, SIDNEY HILLMAN,<br />

by PHIL E. ZIEGLER ................................ 132<br />

Elliot E. Cohen, editor, COMMENTARY ON THE<br />

AMERICAN SCENE, by FRANCES FOX SANDMEL.. ...... 136<br />

THE LAND OF ISRAEL IN 1985. ...................... 139<br />

ILLUSTRATIONS:<br />

MANUEL JOSEPHSON ................................. 122<br />

THE AMERICAN ALCOVE-SALIG KAPLAN MEMORIAL-<br />

TEMPLE ISRAEL, MINNEAPOLIS ................... 13 I<br />

THE AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES BUILDING.. .......... l4O<br />

Patrons for 1953<br />

ARTHUR FRIEDMAN LEO FRIEDMAN BERNARD STARKOFF<br />

Manuscribts for consideration by the publishers should be addressed to:<br />

DIRECTOR, AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES, CINCINNATI 20, OHIO

DIRECTOR: JACOB KADEK MARCUS, rn. D., Adolbh S. Ochs ProfessoroJ3ewbh History<br />

ARCHIVIST: SELMA STERN-TAEUBLER, PH. D.<br />

AMERICAN JEWISH<br />

Crisis and Reaction<br />

HENRY COHEN<br />

72 AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES, JUNE, 1953<br />

by native social conditions? Why did some Jews favor the boycott of<br />

Germany and mass meetings while others opposed both, while still<br />

others favored the boycott but opposed mass meetings? Why were<br />

some Jews lured to support Communist front organizations and Birobidzhan-a<br />

Siberian <strong>Jewish</strong> colony-while others opposed both, while<br />

still others opposed front organizations but supported Birobidzhan?<br />

Why did some Jews support the New Deal in its early days and later<br />

turned against it, while others opposed it in its early days and later<br />

supported it, while still others never supported it? Social analysis is<br />

the pattern that can best group the gopings, and that can demonstrate<br />

that these reactions are not random but are consistent with the<br />

needs of different social groups within the <strong>American</strong> lewish community.<br />

This analysis does not deny other influences-religious or personal.<br />

It simply maintains that the social groupings are important factors in<br />

determining major and minor currents of <strong>American</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> opinion.<br />

It is hoped that through understanding these social influences, the individual<br />

may gain a more objective view of reality.<br />

What were the social groups that formed <strong>American</strong> Jewry during<br />

the thirties and what organizations and periodicals expressed their attitudes?<br />

The "old middle-clas~"~ of German background was composed<br />

of merchants, bankers, real estate men, as well as of the legal,<br />

medical, and rabbinic professions attached to this social class. 'The<br />

voice of this group was heard in the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> Committee<br />

through its Year Book and in the leadership of the B'nai B'rith until<br />

1937 through the R'nai R'rith Magazine. The <strong>American</strong> Hebrew was<br />

one of several periodicals that consistently represented the group's<br />

viewpoint. In this and all other groups, differences between the attitudes<br />

of the leadership and of the rank-and-file can frequently be observed.<br />

The "new middle-classn3 of Eastern European background, from<br />

white collar workers to wealthy business men, supported the <strong>American</strong><br />

<strong>Jewish</strong> Congress and the Zionist Organization of America. This<br />

group's leadership consisted of Reform and Conservative rabbis, other<br />

professional men, and the wealthier business men. The Congress' Bulletin,<br />

Courier, and Index, the ZOA's New Palestine, and Opinion were<br />

organs for this group. The B'nai B'ritlz Messenger of Los Angeles represented<br />

this element as it strove for leadership in the national B'nai<br />

B'rith.<br />

A small but influential group were those manufacturers and business<br />

men of comparatively recent Eastern European origin (along with<br />

their professional appendages) who led a loosely organized movement<br />

sometimes labeled "neo-Orthodoxy" and consisting ol some workers<br />

and members of the lower middle-class. This group was virtually limit-

CRISIS AND REACTION 7 3<br />

ed to large metropolitan centers. Spokesmen for Mizrachi, Hapoel<br />

Hamizrachi, and anti-Zionism were found in its ranks. But some con-<br />

sistency of attitude was discovered in its periodical, the <strong>Jewish</strong> Forum.<br />

And Mizrachi's Jeurish Outlook reflected the dominant Zionist atti-<br />

tude of this element.<br />

A fourth group might be called the "<strong>Jewish</strong> professionals." This<br />

consists of all workers and directors of <strong>Jewish</strong> social welfare organiza-<br />

tions, of center leaders-in short, of all those engaged in secular <strong>Jewish</strong><br />

organizational activity. This heterogeneous group can be divided, for<br />

attitudinal purposes, into individuals economically integrated into the<br />

non-<strong>Jewish</strong> social service world, workers of old middle-class German<br />

background, workers of Eastern European background, and organiza-<br />

tional directors or federation heads. The latter two categories (more<br />

especially the last) favored the program of an "organic <strong>Jewish</strong> com-<br />

munity" and spearheaded (along with some Conservative and Reform<br />

rabbis) the Reconstructionist movement. The <strong>Jewish</strong> Social Service<br />

Quarterly contained a cross-section of the attitudes of these profession-<br />

als. The SAJ Reziew ('The Society for the Advancement of Judaism)<br />

and The Reconstrz~ctionzst reflected the views of those favoring a<br />

stronger secular <strong>Jewish</strong> community.<br />

<strong>Jewish</strong> labor was the most complex group. Union leadership made<br />

itself heard in the editorials of Advance (Amalgamated Clothing<br />

Workers) and Justice (International Ladies' Garment Workers). A<br />

different view held by the rank-and-file of the workers was frequently<br />

apparent between the lines of editorials and in the columns of such<br />

intellectual journalists as the Advance's Charles Ervin. It is true that<br />

during the thirties the proportion of Jews in these unions diminished<br />

considerably. But <strong>Jewish</strong> leadership remained. There were important<br />

divisions of <strong>Jewish</strong> labor along Zionistic lines: The Workmen's Circle<br />

was a socialist anti-Zionist group with a core of Bundists lrom North-<br />

ern Russia, Poland, and Lithuania-a group led by workers with a<br />

consistent working-class and anti-nationalist ideology. Its organs of<br />

opinion were The Call and The Call of Youth.<br />

The National Workers' Alliance represented socialistic Zionism.<br />

This group had a more middle-class orientation: it had many middle-<br />

class leaders; many of its members were from South Russia, where vio-<br />

lent pogroms had given rise to the Poale Zion movement, which grew<br />

in power until its co-operation with other Zionist groups left marks of<br />

middle-class attitudes on the early radicalism of its leader, Ber Boro-<br />

chov. Vanguard, Labor Palestine, and the <strong>Jewish</strong> Frontier spoke for<br />

this group.<br />

The <strong>Jewish</strong> Labor Committee was a defence organization officially<br />

led by members of all <strong>Jewish</strong> labor groups but actuated by the anti-<br />

Zionist members.

74<br />

AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES, JUNE, 19.55<br />

The Stalinist group was composed of a few groping workers and<br />

intellectuals and ruined disillusioned individuals fallen from the mid-<br />

dle-class. <strong>Jewish</strong> Life and the <strong>Jewish</strong> People's Voice spoke for this<br />

group.4<br />

The task of this study is to examine the reactions of these different<br />

groups to the trials of the <strong>American</strong> economy from 1929 through 1939<br />

and to the tragic plight of German Jewry. After the attitudes and pro-<br />

gram of each group are stated, the influence of its social needs and in-<br />

terests on its reaction will be discussed.<br />

I. REACTIONS TO THE AMERICAN ECONOMY, 1929 - 1939<br />

DEPRESSION (1929 - 1932). The <strong>American</strong> Jew was confronted with the<br />

Crash that sent an America so accustomed to prosperity groping for<br />

answers: Why had the wheels of industry and progress stopped turning?<br />

Why were there millions unemployed? And what should Hoover<br />

do about it? <strong>American</strong> Jewry was divided in much the same way as<br />

was the general <strong>American</strong> community.<br />

The old middle-class (<strong>American</strong> Hebrew) maintained, for the public<br />

at any rate, the front of optimism through 1930 and 1931:<br />

We believe that the so-called depression will be short-lived and<br />

that the country with its excellent recuperative powers will be in<br />

excellent shape within a few months.5<br />

Present problems (are) not from weakness, but from the profound<br />

strength of our country. Time has always been a great healer, and<br />

it is no different in the stock market.6<br />

By the summer the crash of last October and its effects will be<br />

pretty much out of the picture.7<br />

And in 1931: "We face 1931 with a spirit of optimism grounded in our<br />

past and in the faith we have in the economic and cultural soundness<br />

of our country."8 In November: "Mlhatever the cause of the setback<br />

that has hit so many so hard, virile America will not long indulge in<br />

lamentation. Though, alas, too many are jobless, the world is still on<br />

the job and the universe spinning in its groove."g And even in March,<br />

1933: publisher David Brown admits that he is optimistic and that<br />

America will come out of this Depression, because it came out of the<br />

others1'-'<br />

These examples show not only optimism but also the belief that<br />

the cure is in the very virility of America, in the past, and in a uni-<br />

verse which will continue spinning in its groove. The charge that<br />

America is indulging in lamentation indicates that the cause is emo-<br />

tional, is one of undue fear. And in 1932, Brown believed that the<br />

cause lay to a great extent in the fear of the consumer (especially the<br />

worker) of buying! The length of the Depression has a "close relation-<br />

ship to the psychology of the worker." It seems that there is some un-

CRISIS AND REAClION 7 5<br />

employment and this instills fear in the worker. He is so afraid that he<br />

cuts down his living expenses and buys less. This only makes further<br />

unemployment. And this is unfortunaie because capital-and this<br />

means, the people-suffers. For "Industry today, great public utilities,<br />

railroads, are all being financed by the people of modest means."ll<br />

But what should be done about the Depression? Industries should<br />

expand.12 The government should not interfere with business; in fact,<br />

the decline in grain and cotton in 1930 was due to the interference of<br />

the Farm Labor Board, which refused to let the law of supply and de-<br />

mand operate.13 In 1931, with more unemployment, 200 million dol-<br />

lars for relief purposes was favored. This might even start the wheels<br />

of business turning.<br />

It is very clear that here is the upper middle-class point of view.<br />

And the German-background Jews ulho had accumulated money for<br />

two generations or more would naturally have this view of the Depres-<br />

sion. It flows quite logically from their position in society. Naturally,<br />

they espoused the theory of fear, the brave public optimism, the faith<br />

in the nature of America and in the past repeating itself, and the<br />

remedy of renewed confidence of investor and worker. All these atti-<br />

tudes we can find in their non-<strong>Jewish</strong> counterparts. The members of<br />

the Chamber of Commerce were the most successful businessmen in<br />

America with accumulations sufficient for considerable investments.<br />

Their president, Silas H. Strawn, in one statement capsulizes all the<br />

views just given in the <strong>American</strong> Hebrezu:<br />

Nations and individuals all over the world are in a state of nerv-<br />

ous hysteria . . . . What is needed most is the restoration of con-<br />

fidence. Why should we not have this confidence? We have had<br />

at least seventeen of these cycles of depressions in the last 120<br />

years. The depression of 1837 was, in many respects, much worse<br />

than this and lasted five years . . . . While I would not minimize<br />

present conditions, I feel very strongly that we are emphasizing<br />

too much the evil factors and that we are overlooking the great<br />

natural resources of our country and the splendid courage and<br />

enterprise of our people . . . . let us awaken in ourselves the lat-<br />

ent spirit of our forefuthers . . . . let those who are complain-<br />

ing of their lot here go to some other country and see how much<br />

better off we are than the people of any other nation on earth.<br />

Let us cease to whine about depression and devote ourselves to<br />

the diligent performance of our daily duties, confident that the<br />

day is not far off when the sun will again begin to cast its warm<br />

rays upon a happy and prosperous people.14 (Italics mine.)<br />

So spoke the <strong>American</strong> old middle-class.<br />

But what were the attitudes of the <strong>Jewish</strong> new middle-class of East-<br />

ern European origin? They had not been in America long enough to

76<br />

AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES, JIINE., 1958<br />

be as thoroughly integrated as their brethren of German background;<br />

nor, for the most part, had they invested their wealth in the same man-<br />

ner. Consequently a comparatively larger number suffered economical-<br />

ly from the Depression.<br />

It is now necessary to distinguish further between the economic<br />

roles of the Eastern Europeans and the Jews of German background:<br />

In his sociological analysis of the White Collar, Charles Mills dis-<br />

tinguishes between the old middle-class (established merchants, some<br />

of whom have been pushed out by the trend towards centralization)<br />

and the new middle-class (white collar people on salaries-managers,<br />

salaried professionals, salespeople, office workers). Because of the new-<br />

ness of Eastern European Jews to the <strong>American</strong> economy, most of<br />

them would fall into the new middle-class. The Jews of German origin<br />

are, of course, members of the old middle-class. Stressing that the<br />

middle-classes are too heterogeneous to have any unity of social phil-<br />

osophy, Mills does make distinctions according to the economic roles<br />

of members of those classes:<br />

In matters of wages and social policies, new middle-class people<br />

increasingly have the attitude of those who are given work; old<br />

middle-class people still have the attitude of those who give it<br />

. . . . Small businessmen, especially retailers, fight chain stores,<br />

government, and unions-under the wing of big business. White<br />

collar workers, in so far as they are organized in unions, in all es-<br />

sentials are under the wage workers. Thus old and new middle-<br />

classes become shock troops for other more powerful and articu-<br />

late pressure blocs in the political scene.15<br />

It may be concluded fro'm a general analysis of <strong>American</strong> society that<br />

the Easter11 European Jews-being in the new middle-class having lit-<br />

tle controlling interests in corporations-would (as Mills puts it) have<br />

the "attitude of those who are given work."<br />

The very meager evidence available for the period, 1929 - 1932,<br />

points in this direction. Opinion is non-socialist but very ffiendly to<br />

Norman Thomas.l"t attacks the Republican platform of ig32.l7<br />

The counterpart of Opinion in the non-<strong>Jewish</strong> world was the Na-<br />

tion. In fact, Horace Kallen and Ludwig Lewisohn wrote for both.<br />

The liberal middle-class view at this time was drifting to the Left.<br />

However, a question-and-answer game between Norman Thomas and<br />

Oswald Garrison Villard showed that the middle-class was friendly to<br />

socialism but still clung to Hobson's theories of cconomics: just put<br />

more spending power into the hands of those who will buy-here is<br />

the voice of the underconsumptionists who would soon spearhead the<br />

New Deal.l8<br />

Labor during the early years of the Depression presented (some-<br />

times simultaneously!) conservative and radical views as to the cause

CRISIS AND REACTION 7 7<br />

of the Crash. At first the leaders told their rank and file members that<br />

the cause was the capitalistic system with its overproduction and technological<br />

unemployment. Uneinployment is due "to the rapid advance<br />

of technology (and) . . . . constantly increasing output."1g That is what<br />

Justice was saying. Along the same line, the Advance claimed that depression<br />

would no longer produce prosperity because technological<br />

unemployment means that prosperity will return fewer and fewer people<br />

to work.20<br />

Six months later the Ad71ance stated that the Depression was not<br />

due to overproduction but to underc~nsumption!~~ This implies the<br />

New Deal school of inflationary economics that would prevent socialism.2"nd<br />

it was on the basis of underconsumptionist theories that<br />

social reform later replaced radical transformation of society as the<br />

labor program.<br />

Regarding the remedies for the crisis there were two similar divisions<br />

of opinion. Following from the view that the cause of the crisis<br />

lay in the social system, public works were discounted as no "solution<br />

of the problems which is inherent in our social ~ystem."~3 (But in the<br />

same breath a six-hour day and a five-day week and unemployment<br />

insurance would be some aid.) In editorials the dominant opinion<br />

favored a re-working of the whole economy: [We need] socialization<br />

of the products of human ingenuity.24<br />

No humanitarian point of view can possibly justify a system that<br />

breeds poverty because that system also creates millionaires who<br />

cast some of their surplus bread upon the waters . . . . The exist-<br />

ing order with its chaotic distribution of wealth by the interplay<br />

of chance, chicanery, oppression and submissiveness, is an ab-<br />

surdity and is indefensible from the viewpoint of economic sense<br />

and ordered progress.*"<br />

Charles Ervin, a consistently radical columnist well into the New<br />

Deal, blasted Republican and Democratic platforms and said that la-<br />

bor will be the loser no matter who is nominated.26 And the Advance's<br />

editorial policy in 1932 was pro-socialist in the election! Clarence Dar-<br />

row's remark that he favored Roosevelt because of four years of<br />

Hoover was (according to the editorial) like the man who said he pre-<br />

ferred stale bread because he had just drunk four cases of hooch. The<br />

alternative to bad hooch is good whiskey-not stale bread!2i<br />

Despite the official socialistic ideology of the unions during the<br />

depression period, Sidney Hillman and Jacob Potofsky came up with<br />

concrete programs that were anything but socialistic. The Hillman<br />

Plan, that eventually sent Hillman to the conference rooms with the<br />

Chamber of Commerce to plan the NRA, advocated "staggered ein-<br />

ployment," shorter work days and hours, unemployment insurance<br />

from the funds of industry, and a Board of Industry for long-range

78<br />

AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES, JUNE, 1953<br />

planning.28 Potofsky's program added to this high wages, public works,<br />

and housing projects.29 Whereas the Advance had previously told the<br />

workers that such reforms were not sufficient and that only a complete<br />

reshaping of the economy would be the sound answer, it now claimed<br />

that reform was desirable.<br />

What conclusions can be drawn from these conflicting views? It is<br />

known that the <strong>Jewish</strong> workers were largely from the socialist (Bund<br />

or Poale Zion) groups of Eastern Europe. But their leaders were prom-<br />

inent in the anti-socialist New Deal. Would it not be a logical policy<br />

of union leaders (who for whatever reasons had more middle-class<br />

views) to write about the evils inherent in society, to say that only a<br />

radical transformation could improve conditions? This they must say<br />

to keep the support of the workers. But the program they adopted was<br />

one of social reform sanctioned by big business interests. For these<br />

union leaders were wearing white collars and were clothed also in the<br />

ideological garb of the capitalistic world. They held positions that<br />

brought them into conference rooms with the leading powers and<br />

politicians of the land. But no "old-world socialists" would be allowed<br />

in this capitalistic planning. So while frequently resorting to radical<br />

terminology, they spoke simultaneously in terms of undaconsump-<br />

tion and a respectable reform program.<br />

Exactly the same trend can be seen in the non-<strong>Jewish</strong> unions. True,<br />

socialist sentiment was stronger among <strong>Jewish</strong> workers than among<br />

non-<strong>Jewish</strong> workers-because only a small percentage of the general<br />

<strong>American</strong> proletariat was fresh from European socialist movements,<br />

whereas, practically all the <strong>Jewish</strong> workers had just emigrated from<br />

such movements in Eastern Europe. In the <strong>American</strong> Federationist,<br />

edited by William Green, an official organ of the AFL, are found state-<br />

ments supporting underconsumptionist theories:<br />

The purchasing power of consumers will determine the level of<br />

production. (Since this power has dropped,) business must turn<br />

its attention to the deliberate development of consumer buying<br />

power in order to restore and maintain prosperity. Every employ-<br />

er, public or private, who cuts wages is working against revival<br />

of business and a restoration of production activity.30<br />

It would seem that Green could afford to be less radical in his publi-<br />

cations than could the ACWA or ILGWU since he had a much smaller<br />

percentage of radicals in his unions. However, before the 1932 AFL<br />

Convention, Green spoke radical words that shocked the Nezu York<br />

Times and pleased the left-wing publishers of Labor Age when he<br />

made the following statement concerning the six-hour day and the<br />

five-day week: "The world must know we must be given it in response<br />

to reason or we will secure it through forces of some kind!"31 But by

CRISIS AND REACTION 7 9<br />

and large Labor Age was dissatisfied with Green's analysis and claimed<br />

that capitalism was collapsing. The only answer of capitalism is wage<br />

cuts, and these will only deepen the crisis. "Across the whole indus-<br />

trial world falls the shadow of Karl Marx."32<br />

NEW DEAL (1933 - 1939). All groups of <strong>American</strong> Jews had decided<br />

reactions to the Roosevelt remedy in its various phases. Three indices<br />

of opinion will be noted: The New Deal in its early days of Blue<br />

Eagles and pump-priming; attacks on the New Deal centering around<br />

the Supreme Court controversies of 1935-36; the "recession" of 1937<br />

when ten million were unemployed and production had fallen to 20%<br />

below the 1929 level-followed by the preparedness program which<br />

ushered in a new era of expansion.<br />

It will be recalled that the "old middle-class" Jews of German<br />

background echoed the voice of the Chamber of Commerce (or vice-<br />

versa). And in 1933, as the <strong>American</strong> Chamber of Commerce helped<br />

write the NRA, the <strong>American</strong> Hebrew was shifting to the New Deal<br />

position. David Brown attacked the opponents of the NRA with their<br />

stand-pat capitalism of another day!33 And Brown is all praises for<br />

Hugh "Sock-in-the-nose" Johnson.34 Brown admits having been a<br />

Hooverite-Republican but explains that he has been pleasantly sur-<br />

prised by Roosevelt.35<br />

-<br />

In thk stormy years of 1935-36, when H. L. Mencken in the Ameri-<br />

can Mercury was leading his last barbed attacks against Roosevelt<br />

("Quacks are always friendly and ingratiating fellows . . . ."),36 he<br />

spoke for many Jews and non-Jews of the old middle-class.<br />

Not for all, by any means, because, as Mills maintains, "the politi-<br />

cal psychology of any social stratum is influenced by every relation its<br />

members have, or fail to have with other strata . . . ." And there was<br />

great diversity, even in the old middle-classes. Still, many members of<br />

the old middle-class would naturally oppose the New Deal at this<br />

time. They possessed the reserve of middle-class wealth. They were, by<br />

and large, the people more closely affiliated with the larger corpora-<br />

tions. Some were living on fixecl incomes and so they wanted to stop<br />

the inflation. And, as Mills pointed out, the members of this group<br />

would tend to have the attitude of those who give jobs.37<br />

Although the <strong>American</strong> Hebrezu editorially took no sides in the<br />

election, some wealthy Jews of this class campaigned on Landon's<br />

behalf.38 James \Warburg in his Hell Bent for Election calls the New<br />

Deal socialism!" An A.merican Hebrew columnist opposes Roosevelt's<br />

Supreme Court Plan as he praises Governor Lehman for not swallow-<br />

ing "the court reform plan, hook, line, and sinker, for the sake of good<br />

old democracy."'O<br />

There is no record of this group's endorsing the preparedness pro-<br />

gram-despite the Hitler menace to the Jews-any sooner than did

80 AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES, JUNE, 1953<br />

Gentiles of the same social class. In 1937 the <strong>American</strong> Hebrew hailed<br />

the appeasement policy of Leon Blum: Instead of aggression, "Blum<br />

proposes to reverse the process and to pull the Hitler fangs in the in-<br />

ternational scene with kindness and conciliation. That is the <strong>Jewish</strong><br />

way."41 But as the International Chamber of Commerce was told that:<br />

"The potential strength of the peace-loving nation is the essential<br />

stabilizing influence in the world today . . ." and that "the super-<br />

nationalism which seeks a self-contained economy as the greatest good<br />

(is) unsound . . . ,"42 the <strong>American</strong> Hebrew gradually came over to the<br />

policy of firmness towards Hitler. A United States preparedness pro-<br />

gram would make the Fascists think twice before beginning a war.43<br />

That the reaction of the <strong>Jewish</strong> old middle-class to the Depression<br />

and New Deal flows from its social position seems obvious from the<br />

evidence given. That its members follow the reaction of their Gentile<br />

social counterpart (from the early view of the Depression which re-<br />

flected Silas Strawn's statement to riding the waves of the preparedness<br />

program)-this is indirect proof. This element was not likely to criti-<br />

cize sharply a society that had bestowed upon it so many real blessings.<br />

Jews of the old middle-class might well be even less likely than Gen-<br />

tiles to look for flaws in the existing order. For their pattern of <strong>Jewish</strong><br />

life was directed to the proposition: <strong>American</strong> society is our salvation,<br />

and because we have become integrated into that society, we are in a<br />

position to enjoy the great opportunities which it offers. If they were<br />

to believe for a moment that there was something fundamentally<br />

wrong with society, they would be undermining their whole position<br />

as <strong>American</strong> Jews and would be without a Jerusalem.<br />

What were the attitudes of the Eastern European new middle-<br />

class during the New Deal? Along with the majority of <strong>American</strong>s they<br />

supported Roosevelt's early program.44 They were especially attracted<br />

by technocracy-an economic messianism that opposed the existing so-<br />

cial order and proffered a government by scientists and engineers who<br />

would give new relative values to all commodities and eliminate the<br />

present price system. Roosevelt and the NRA, Opinion claimed, were<br />

moving towards technocratic goals45 The Nation was briefly attracted<br />

to technocracy but soon decided that this pseudo-economics was<br />

"scrambled egg~."4~<br />

When some segments of the pcpulation turned against the New<br />

Deal, the new middle-classes remained loyal. In 1936, Bernard Rich-<br />

ards wrote in the Jezuish Spectator about "Roosevelt-Friend of the<br />

Oppressed," and Lewisohn in the same issue called his voice "the voice<br />

of reason, humanity, and authentic hope,"47 even as did The Nation.<br />

Regarding the preparedness program, The Congress Bulletin main-<br />

tained that "The United States does not turn militarist because the<br />

President demands a greater air force and equipment for a minimum

CR~S~S AND REACTION 8 1<br />

army." This was on Armistice Day, 1938. The Nation had already ad-<br />

vocated the cash-and-carry program48 . . . . despite the cries of Oswald<br />

Garrison Villard, who saw very clearly the relation between the re-<br />

cession and t.he re-armament. He even quoted the Roosevelt of 1936:<br />

(Employment through armament) is false employment, it builds<br />

no permanent structure and creates no consumers' goods for the<br />

maintenance of a lasting prosperity. We know that nations guilty<br />

of these follies inevitably face the day when either their weapons<br />

of destruction must be used against their neighbors or when an<br />

unsound economy like a house of cards will fall apart.49<br />

The evidence shows that the <strong>Jewish</strong> new middle-class followed<br />

generally the same lines as the non-<strong>Jewish</strong>. If anything, they seemed<br />

a little more naive with their gullible acceptance of technocracy. More<br />

important is the eagerness for preparedness. Because of the keenness<br />

with which they felt the Hitler tragedy, the Villardian element was<br />

absent in their counsels.<br />

While the new middle-class, after crisis, entertained an ideology<br />

which called for replacing the existing social order, it never developed<br />

a program which would challenge that order. Its extreme plight in<br />

time of crisis would lead this group to search for scientific solutions<br />

and to use radical phrases. However, its desire for the well-being and<br />

privileges of new middle-class status would preclude a program that<br />

would abolish the social structure which grants such a status.<br />

What did the neo-Orthodox group led by manufacturers and busi-<br />

ness men think was the cause of the Depression? An interesting article<br />

in the January, 1936, <strong>Jewish</strong> Forum by a midrashic-economist deals<br />

with the Depression and reads like a page from the Soncino Talmud.<br />

The author seems to be attempting to lay the blame on a group of<br />

large property-owners and big bankers-not on the manufacturers and<br />

labor. (This sounds as though it were written for worker consumption).<br />

He first talks about the "so-called 'upper-strata' of society, the prop-<br />

erty-or land-owners." Then he throws in from Midrash Rabba a<br />

homily about the land-owner Cain versus the good producer, Abel.<br />

These Cain-ites . . . . "These lords of the land withhold the opportun-<br />

ity of using (money) intensively until capital and labor are compelled<br />

to give up the lion's share of the future products for the mere permis-<br />

sion jointly to produce wealth." Through high taxes the government<br />

then takes too much of the wealth that is produced. Therefore, Jews<br />

(capital and labor) should unite against the property class and the gov-<br />

ernment. Who are these property classes? Do they own property which<br />

the producers must rent? Or are they the bankers and holding com-<br />

panies who have power over "the opportunity of using money"? Prob-<br />

ably they are the latter, as the author condemns them: "The so-called

8 2 AMER~CAN JEW~SH ARCHIVES, JUNE, 1953<br />

owners of these opportunities create fictitious booms guilefully to en-<br />

tice the simpletons to invest their last savings in their holdings."50 So,<br />

the bankers and government become scapegoats for the Depression.<br />

The Forum was, however, enthusiastic about the early days of the<br />

New Deal. In fact, the idea of a five-day week (the NRA) had its ori-<br />

gins-says the Forum-in <strong>Jewish</strong> circles: a Dr. Sam Friedman brought<br />

it to the attention of the AFL.51 In addition to the NRA, the Torah<br />

was spoken of as a solution to the economic problems: When Israel is<br />

at home with the Torah, then will their problems be solved.52 Since<br />

trade will always reward the industrious and deny those lacking in<br />

industry, the problem of interaction between wealth and poverty will<br />

always be present. Since there will always be rich and poor, the poor<br />

should not be "envious of the possessions of the rich," and the rich<br />

should not be "self-centered and greedy."53 The proletariat should not<br />

lose hope: as Rabbi Jung put it, hereditary proletarianism should be<br />

an impossibility; this is the meaning of the Jubilee Year.54 This seems<br />

to be a call to the worker not to collapse into proletarian ideologies.<br />

Dr. H. I. Schenker writes that all current political programs are sim-<br />

ply catch phrases to ease the poor man's soul. What is needed, he says,<br />

is improvement of the ethical individual: "Superman, in the Biblical<br />

sense, enters into the formation of a supercommunity; the supercom-<br />

munity enters into the formation of a supernation; and a supernation<br />

serves as the nucleus for a super-humanity-that is, in short, the Judaic<br />

scheme of social justice."55<br />

Regarding preparedness, the Forum said of Roosevelt's Chicago<br />

speech (1937) that a "great service has been rendered humanity."5"<br />

And from that point on the Forum supported preparedness.<br />

The needs of the specific group of manufacturers and businessmen<br />

are seen in these attitudes: the existing economic and social order is<br />

basically sound. Its difficulties do not stem from the manufacturers or<br />

their employees. With most management, they support the early New<br />

Deal. But, by 1936, they assert that the Depression is caused by big<br />

bankers and government. Manufacturers may have felt hostile to those<br />

on whom they were dependent for credit. The Orthodox worker was<br />

persuaded that he and his employer had identical interests and en-<br />

emies.<br />

Religious authority-more meaningful to this group than to the<br />

middle-class-was used to strengthen loyalty to institutions which had<br />

offered undreamed of opportunity and protection. Although it was ad-<br />

mitted that economic inequality existed, it was pointed out that this<br />

was part of the divine order of things. Political programs give no<br />

answer. But if men are good individuals (the rich should be good rich<br />

and the poor should be good poor) and follow the Torah, then they<br />

will be happy.

CRISIS AND REACTION 83<br />

The heterogeneity of the <strong>Jewish</strong> professionals has been noted, and<br />

so views of the old and new middle-classes and of academicians would<br />

be expected. Louis Kirstein of Filene's Department Store, after urging<br />

<strong>Jewish</strong> support of the New Deal, gives an interesting reason:<br />

I think that it is particularly fitting for Jews to help in this pro-<br />

gram because certainly the NKA has done a great deal for the in-<br />

dustry in which so many Jews are interested and engaged in, and<br />

that is the needle industry, and the distributive trades, to say<br />

nothing of the great good that has been accomplished in the elim-<br />

ination of the sweat shops.57<br />

This was the old middle-class in January, I 934.<br />

In June of that year the new middle-classes are addressed and en-<br />

couraged by Morris Krugrnan. In true new middle-class tradition, he<br />

shows technocratic sympathies: " . . . . engineers and economists are<br />

just beginning to realize that they are working towards the same ends."<br />

He then encourages the white collar workers: "Wholesale redirection"<br />

of vocations will not be necessary, for "when employment opportuni-<br />

ties occur again, the proportion of white collar workers to others will<br />

probably be greater than it has been in the past."58<br />

There is also the pessimism of the detached academic theorist:<br />

. . . Capitalism cannot solve its own problems of employment<br />

(and) has entered into a stage of contraction therefore. Those that<br />

don't like the word "contraction" call it "stabilization . . , ." The<br />

NRA is . . . . a sort of return to the guild psychology. It is a mani-<br />

festation of a scarcity consciousness, and perhaps that scarcity con-<br />

sciousness is there with very good reason. It is an intelligent atti-<br />

tude, because, as I look upon it, I think that capitalism has seen<br />

its best days.<br />

But socialism will not be next:<br />

I do not share that optimistic view. I look upon the modern west-<br />

ern world as a society which, if the world were governed by logic,<br />

would have to go on to socialism, but the world not being gov-<br />

erned by logic, but by psychology and by the fear of strong<br />

vested interest groups, I am afraid that the trend or the next step<br />

does not lie in the direction of socialism or communism, outside<br />

of Russia.59<br />

And so the academic world has gone left.<br />

What would be the attitudes of that group of immigrant social<br />

workers and federation heads who spearheaded the Reconstructionist<br />

movement? Dependent on support of the <strong>Jewish</strong> communities, these<br />

federations suffered tremendously during the Depression. Salaries were<br />

cut to such an extent that a threatening "rank-and-file" movement<br />

grew up anlong the workers-<strong>Jewish</strong> and Gentile. The financial re-

84<br />

AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES, JUNE, 1953<br />

ports and problems of the federations told them that the New Deal<br />

was not succeeding. The groups furthermore were in close touch with<br />

the relief needs of America. Since they were in touch with the vast<br />

number of unemployed, they had an increased awareness of the fail-<br />

ures of the New Deal. Abraham Duker, Harry Barron, and Nathaniel<br />

Bronstein were members of a committee that drew up a paper at the<br />

Practitioners' Session of the 1935 National Conference of <strong>Jewish</strong> Social<br />

Service. In view of the influences noted above, the following skepti-<br />

cism towards the New Deal might be expected:<br />

. . . . After two years of the New Deal, we can see that this attempt<br />

to benefit the forgotten man and business has resulted only in<br />

bringing benefits to industrial owners . . . .<br />

Profits and dividends of the large industrial concerns were not<br />

only safeguarded, but increased as much as 600 percent in 1934<br />

over 1932. In contrast to this we find that during this period the<br />

(real) wages of the industrial worker declined . . . . Speed-up and<br />

mechanization have further intensified the problem of unemploy-<br />

ment and have helped considerably in swelling the number of un-<br />

employed. In agriculture under the New Deal we find the lower-<br />

ing of income, reduction of standards of living, increase of ten-<br />

ancy, forced sales, mortgage indebtedness, and heavy taxes. Un-<br />

employment stood at i7,157,000 men, women, and young workers<br />

in November, 1934. This is 800,ooo more than the estimate for<br />

November, 1933.60<br />

An examination of The Reconstructionist gives abundant evidence of<br />

this group's views. What do they want? ". . . . a thoroughgoing change<br />

in our social and economic order . . . . establishment of a co-operative<br />

society, the elimination of the profit system and the public ownership<br />

of all natural resources and basic industries."61<br />

Meanwhile, however, they will struggle with labor for more equal<br />

distribution of the income of industry. A radical program is to be<br />

achieved through reformist measures-but true reforms, not the pseu-<br />

dereforms of the New Deal.<br />

The Reconstructionists reverse the pattern of the old middle-<br />

classes with the latter's initial support and later attack against the<br />

New Deal. The avid disapproval of The Reconstructionist gives way<br />

by 1937 to acceptance and even support of the New Deal program.<br />

Roosevelt is unpacking the Court, cries The Reconstructionist.62 And<br />

the social justice committee of the Rabbinical Assembly, a committee<br />

composed of some Reconstructionists, admits that the New Deal is of-<br />

ten inconsistent but should be supported because it is in the right<br />

human s~irit.63<br />

The attacks against the New Deal program have been explained.<br />

But why this change in attitude? The leftist groum rallied around the

CRISIS AND REACTION 85<br />

New Deal whenever it was seriously attacked in 1936 and 1937. After<br />

all, these Reconstructionists were not leaders of a revolutionary movement.<br />

They were primarily concerned with repairing the faults in the<br />

structure. Hence, although they may have liked more sweeping reforms,<br />

they nonetheless rallied to the support of Roosevelt whenever<br />

a threat existed that even the minimum program was in danger.<br />

The Reconstructionist was slow to shift >way from its stand on<br />

neutrality. After the President's Chicago speech, it stated: "Our real<br />

danger is that the interests that would profit by our participation in<br />

the war, both those of <strong>American</strong>s and of foreigners, will be able to beguile<br />

us with plausible idealistic reasons for joining it."64 Recognizing<br />

preparedness as an attempt to solve an economic problem: "NO economic<br />

crisis can be as tragic as the death of a single man on the battle<br />

field." And of the possible war: "(It will be a war of) conflicting imperialisms<br />

and there is mighty little moral principle at stake."65<br />

After Munich, this attitude changes and the Christian Century is<br />

attacked for its pacifism: "If military aggression is a crime, then to invite<br />

such aggression by military weakness is to make oneself in part<br />

responsible for the crime . . . . Until the fiasco of the Munich pact The<br />

Reconstructionist favored a policy as is now advocated by the Christian<br />

Century." But now America must be strong. (February 10, 1939.)<br />

Torn between its opposition to the use of preparedness in solving<br />

national economic problems in an ultimately unhealthy way and its<br />

recognition of the menace of Hitler, The ~econstructio~ist slowly began<br />

to give its support to a strong America. Lying somewhere in between<br />

the new middle-classes and the Socialist organizations on the<br />

political spectroscope, the ~econstr.uctionists-more quickly than the<br />

Socialists but more slowly than the new middle-classes-came to the<br />

support of the preparedness program.<br />

In the world of Gentile social work, there is the same divergence<br />

of opinion as in the <strong>Jewish</strong> group: New Dealer Hany Hopkins addressed<br />

the National Conference of Social Work in Detroit-July,<br />

1933.66 The radical voice was that of Miss Mary Van Kleeck, whose<br />

fiery speech set the tone of the 1934 conference: Social workers should<br />

dispel the illusion that the New Deal is trying to creare. She thus<br />

characterizes the New Deal: "How far must government yield to the<br />

demand for change in the status quo in order to maintain the status<br />

quo?" We need, she said, a form of collectivism that is neither fascism<br />

nor communism. Miss Van Kleeck was director of the department of<br />

industrial studies at the Russell Sage Foundation. She found support<br />

from a large minority at the conference.07<br />

Although it is impossible to ascertain statistically, there is some<br />

indication of less radicalism in the ranks of Gentile social workers<br />

than in those of the <strong>Jewish</strong>. Two factors may account for this: The

86 AMER~CAN JEWISH ARCHIVES, JUNE, 1953<br />

Gentile federations received their backing not just from old middle-<br />

classes but from big industrialists who were not hard hit by the De-<br />

pression. So non-Tewish federation leaders were in better financial con-<br />

dition than weri the <strong>Jewish</strong> and were not so likely to scc the inade-<br />

quacies of the New Deal. Furthermore, the radical influences of an<br />

Eastern European proletarian ideology did not appear in the non-<br />

<strong>Jewish</strong> group.<br />

Before analyzing the differences in reactions of Labor Zionists and<br />

Bundists, it is necessary to examine the attitudes of the most conserva-<br />

tive branch of <strong>Jewish</strong> labor-the union leadership. The dual attitude<br />

of the union leaders from 1929 to 1932 has been obselved: an official<br />

socialism and yet a social reform prog~am based on underconsump-<br />

tionist theories. It was seen that the radical front was needed to keep<br />

the support of the workers. But with the New Deal's labor program<br />

and propaganda, it was finally possible to drop the pretense of radical-<br />

ism and to hail the New Deal.<br />

Yet, from January through May, 1933, the voice ol Jacob still was<br />

radical while the hands of Esau were clasping the New Deal eagerly.<br />

Technocracy was looked upon as a complete neglect of social and polit-<br />

ical power problems and as an influence that would distract from the<br />

real problem of how to wrest social contro'l Erom the anti-social ele-<br />

ments. (This would make it seem that the new middle-classes wel-<br />

comed the opportunity to dodge the real problem.)68 Whilc the Hill-<br />

man plan for social reform was being hailed on the editorial page,<br />

Charles Ervin was writing (as if on behalf of the forgotten workers)<br />

that Roosevelt does not understand that the hull of the ship of state<br />

is too broken down for any kind of patch-up job.6"<br />

In June, 1933, there is the first official endorsement of the New<br />

Deal-"an entirely new departure from <strong>American</strong> legislative prac-<br />

tice."70 The NRA was adopted, because the Depression showed that if<br />

"businessmen and bankers were left to lead the country to recover by<br />

their own wisdom and considerations, there would never be any re-<br />

covery."71 But surely Sidney Hillman, who worked with the Chamber<br />

of Commerce in planning the NRA, knew that <strong>American</strong> business was<br />

behind the NRA and the 1933 New Deal! The Junc issue was New<br />

Deal all-the-way. Even Charles Ervin writes that if the workers organ-<br />

ize well as a result of provision 7a, they will come out of the period<br />

with gains in conditions and wages.72<br />

It is from Ervin-a labor intellectual-that one hears the last ex-<br />

pressions of the old radicalism. In October, 1933, he remarks that the<br />

chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufactur-<br />

ers have their new offices in the NRA.73 And in February, 1934, he<br />

stresses that the purpose of the NRA is to re-create the pro-business<br />

conditions of the twenties-the NRA is an uphill struggle.74

CRISIS AND REACTION 87<br />

Hillman, meanwhile, argues that while the NRA may have been<br />

meant as aspirin, it will still help change the system; that one should<br />

distinguish between what was meant and what will happen.75 In the<br />

fall of igyj, Hillman was appointed to the National Industrial Rela.<br />

lions Board. And fromi 1935 on, the progress made by the New Deal<br />

was ~tressed.~Vn 1936, progressive labor is committed to the re-election<br />

of Roosevelt, and even Charles Ervin wrote warmly of FDR's<br />

convention speech.77<br />

Now completely in the New Deal orbit, the Advance saw the recession<br />

only as the result of not enough New Deal! "Is it possible that<br />

so soon the lessons of yesteryear are forgotten!" Therefore, enact more<br />

labor legislation.78 And, in September, 1938, America should call the<br />

bluff of the Fascists. There was all praise for Roosevelt's "clear and<br />

clean reaction to the German gangster-government's savage campaign<br />

of destruction of the defenseless Jews of Germany."79 It is interesting<br />

to note that the Hitler campaign against the Jews was not stressed in<br />

the Advance until non-Jews of the same class were ready to take up<br />

arms.<br />

The Labor Zionist group, while having many middle-class members<br />

in its leadership and while being an intensely nationalistic group,<br />

claimed to be socialistic and attacked Roosevelt's early program. In<br />

1935, when union leaders were supporting the New Deal, the Frontier<br />

stated that a vote for the administration was a vote for a relief program<br />

and not lor intelligent economic planning.80 The Frontier bemoaned<br />

the fact that the socialist vote was only a protest.s1 Still some<br />

Labor Zionists supported Roosevelt-and these Labor Zionists were not<br />

only Reform rabbis in the movement's leadership. The Labor-Zionist<br />

Newsletter stated in 1937 that the New Deal should be supported<br />

against reaction, as long as one is not fooled by the "amorphous sea of<br />

Roose~eltism."8~ In 1939, this group favored a "benevolent neutrali-<br />

ty." Military expenditures were approved, for they would inspire fear<br />

in the fascist nations. Besides, the worlci is not black and white, and<br />

in the event ol: war, the democratic countries should win.83 This de-<br />

parture from strict socialist doctrine was made with explicit qualifica-<br />

tions by the LeEt Poale Zion group: "The struggle against fascism<br />

must . . . . be permeated with the struggle against capitalism. Al-<br />

though the blade may temporarily be dulled by tactical motives, we<br />

must not for one single moment lose sight of the fact that the final<br />

struggle is against capitalism, the evil of evils."84 Still the departure<br />

was made.<br />

And so, along with the most radical of the middle-class (the <strong>Jewish</strong><br />

professionals), the Labor Zionists at first attacked the New Deal. Then,<br />

as Roosevelt was placed under heavy fire by conservative interests in<br />

1936, they (and the Reconstructionists) s~vitched to qualified support

88 AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES, JUNE, 1953<br />

of the New Deal. The Labor Zionists, liaving a rank-and-file of socialistic<br />

workers, were somewhat more reluctant to support the Kew Deal<br />

than were the Reconstructionists. Still their partially middle-class<br />

leadership and the organizational needs of Labor Zionism to sheathe<br />

the sword of the class struggle in order to work with other Zionist<br />

groups underlay the driit &om a radical working-class ideology to a<br />

sanctioning of social reform and support of capitalistic delnocracies in<br />

the Second Mrorld War.<br />

In the Workmen's Circle (its youth magazine, Call of Yorrth, and<br />

its official Workmen's Call) there is found the most consistent social<br />

philosophy of all <strong>Jewish</strong> groups. Consistency does not prove truth, but<br />

at least the Circle begins the Depression with a radical revolutionary<br />

philosophy and is never drawn, before the outbreak of World War IT<br />

(along with the other leftist

CRISIS AND REACTION<br />

At last has reappeared.<br />

It really wasn't lost at all:<br />

It was hiding behind my beard.<br />

BRANDEIS: And I am Louis Brandeis.<br />

A liberal I'm supposed to be.<br />

It never does you any good,<br />

Because I'm in the minority.<br />

It makes a perfect set-up<br />

For Morgan and his minions.<br />

The masses are demanding bread,<br />

And they get dissenting opinions!!8"<br />

The intimation of the Brandeis speech is significant since it shows the<br />

liberal and conservatives conspiring against the people.<br />

The Workmen's Call sees in the 1937 recession evidence that the<br />

New Deal has been unable to save <strong>American</strong> capitalism without re-<br />

sorting to a dangerous armament program:<br />

. . . . the palliative measures enacted (by the New Deal) . . . . did<br />

much to alleviate the suffering of the destitute . . . . and they un-<br />

doubtedly did give a fillip to industry which for a while sent pro-<br />

duction levels soaring and provided increased employment and<br />

purchasing power for millions-a not inconsiderable achievement;<br />

but alas, his methods were nonetheless palliatives. (The crash ,<br />

came) with punctual fidelity.<br />

Despite the illusion of purposeful activity so ingenuously treat-<br />

ed by his tirades against big business, Roosevelt's policy in this<br />

second stage of the New Deal is essentially one of drift. He has<br />

submitted no new legislation of importance in the past month,<br />

nor is any in the offing. His positive measures have been limited<br />

largely to reducing relief appropriations and sky-rocketing arma-<br />

ments expenditures. The latter-a sop to heavy industry- may<br />

serve to relieve economic distress, but at best it is a temporary ex-<br />

pedient which must inevitably lead to a new and more precipitate<br />

decline and which enhances a thousand-fold the danger of em-<br />

broiling this nation in world conflict.90<br />

Following this analysis of the relation between recession and prepared-<br />

ness, and in consonance with the Workmen's Circle's anti-nationalist<br />

ideolagy, Harry Gersh in January, 1939, attacks the "Dangerous Ap-<br />

plause" with which the confused <strong>Jewish</strong> community greets Roosevelt's<br />

anti-Hiller speeches. This bravado is simply a means by which the<br />

<strong>American</strong> ruling powers can edge the people towards militarism.91<br />

The Workmen's Circle was the only <strong>Jewish</strong> group that did not ac-<br />

cept the preparedness program before the outbreak of World War 11.<br />

After the invasion of Poland, there was dissension in the ranks as to<br />

whether or not to support preparedness: some said the socialists could<br />

get concessions from the capitalists in return for their support;92

90<br />

AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES, JUNE, 1953<br />

others countered that a victory for the Allies would mean defeat of<br />

revolution in the defeated nations and continued exploitation of<br />

colonial pe0ple.~3 The editorial policy eventually took the first view.<br />

In view of the social background of the Circle, it would certainly<br />

be expected that this group would have the most critical and consist-<br />

ent analysis of the capitalist system. A group enjoying few benefits<br />

from that system did not need to rationalize on its behalf. And the<br />

Circle was workman-born, bred, and led, with none of the New Deal<br />

connections of the Advance. The Circle was a proletarian group of<br />

long-standing. While Labor Zionism had to cooperate with middle-<br />

class Zionist leaders in its quest for power in the world Zionist move-<br />

ment, the <strong>Jewish</strong> Bund did not have a similar organizational need.<br />

Consequently, this group could analyze the Depression, New Deal<br />

remedies, and the Recession without concern for the survival of capi-<br />

talism. In their eyes the Recession showed that the great challenge of<br />

capitalistic overproduction was still far from solved in a pea~e-time<br />

economy.<br />

This concludes the analysis of the reactions of <strong>American</strong> Jewry to<br />

the Depression and the New Deal. The reaction of each group has<br />

been shown. The tremendous influence of the status of that group in<br />

society on its reaction has also been demonstrated. The old middle-<br />

class could not doubt thc merit of that system which had produced<br />

such prosperity and which had bestowed so many palpable benefits;<br />

and so it spoke of faith in America and opposed preparedness until<br />

the International Chamber of Commerce condemned a "self-contained<br />

economy" as super-nationalism. Orthodox manufacturers and business<br />

men could blame neither manufacturers nor the workers they em-<br />

ployed, so they said that the government and bankers caused the De-<br />

pression and they emphasized the crucial importance of religious ideol-<br />

ogy. The new middle-class, the Reconstructionists, and the Labor<br />

Zionists (reading from right to left) all expressed varying degrees of<br />

political ambivalence. They all felt the crisis keenly and spoke of<br />

radical solutions. The new middle-class, dependent on the existing<br />

order for its new-found status, was the first to support the reforms of<br />

the New Deal. The Reconstructionists, although more reluctant, final-<br />

ly supported the New Deal. (Social workers would rather have a mini-<br />

mum program of reform than none at all.) Last of the three to sup-<br />

port Roosevelt was the Labor Zionist group: its partially middle-class<br />

leadership, institutional needs, and inore emotional approach to na-<br />

tionalism led this group to deviate from an orthodox, socialistic ap-<br />

proach. Only the <strong>Jewish</strong> Bund, workman-born, bred, and led, seemed<br />

to follow a consistently socialist ideology. The <strong>Jewish</strong> groups followed<br />

the pattern of their non-<strong>Jewish</strong> counterparts, unless specific needs dic-<br />

tated otherwise.

CRISIS AND REACTION<br />

11. REACTIONS TO HITLER<br />

The advantages of hindsight provide the observer today with an ob-<br />

jective understanding of what caused the Nazi regime and why the<br />

Jews were chosen for extermination. But <strong>American</strong> Jewry of the<br />

thirties had no such hindsight and was bitterly divided as to what<br />

underlay Nazism and as to what its answer to it should be.<br />

Today it is commonly recognized that the fascist solution was re-<br />

sorted to by German industrial leaders. Their world market was very<br />

limited by the competition of thosc countries which won the First<br />

World War, and buying power at home had become insignificant. So<br />

wages were cut, and this could be done (since standards were already<br />

so low) only through a fascist dictatorship. But someone had to be<br />

blamed for the privations of the populace. So the traditional scape-<br />

goat in Germany, the Jew, was used as the target for the antagonism<br />

and frustration of the German masses.94<br />

Groups within A~nerican Jewry immediately differed as to what<br />

their answer to Hitler sholild be. Some hoped that an economic boy-<br />

cott would weaken a German economy which desperately needed an<br />

export trade sufficient to pay for those imports required for rearma-<br />

rnent.95 Others considered mass meetings to be an effective counter-<br />

move. And most Jews felt that the Voice of America-the protests of<br />

our government-would arouse the conscience of the world and that<br />

Germany would then respond to world opinion. The hindsight of<br />

history has shown that Germany feared neither mass meetings nor the<br />

Voice of America so long as the words were not backed by action. And<br />

the action of the Allies was determined independently of the rhetoric<br />

in Madison Square Garden and the remarks of <strong>American</strong> officials that<br />

often prompted apologies from the State Department to the Nazi gov-<br />

ernmen t.96<br />

These differences in programs to combat Hitlerism were based on<br />

the much more important differences in interpretation of the cause<br />

of Nazism. Since the economic and social problems which Germany<br />

faced were not confined by national boundaries, it was important that<br />

<strong>American</strong> Jewry and all America should understand the crisis of Ger-<br />

many. And yet, many segments of <strong>American</strong> Jewry never saw Nazism<br />

as a result of a most desperate economic and social crisis. Anti-Semit-<br />

ism was rarely seen as necessaly for the preservation of the basic social<br />

structure in Germany. Little wonder that ineffective programs were<br />

hailed as salvation as <strong>American</strong> Jews spent their energies attacking<br />

each other.<br />

To understand precisely how <strong>American</strong> Jewry differed as to the in-<br />

terpretation of thc rise of Nazism, and therefore differed as to counter-<br />

programs, it is helpful to return to social analysis and to discover just

g2<br />

AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES, JUNE, 1953<br />

what the reaction of each group was and how that reaction was af-<br />

fkcted by status in society.<br />

What were the old middle-classes of German descent saying from<br />

1930 through March 19, 1933, when the Reichstag abdicated? Let the<br />

<strong>American</strong> Hebrew speak for itself:<br />

(September 19): "The successes of anti-Semitic parties in Ger-<br />

many possess no quality of permanence." Why? Germany would<br />

not want to lose the respect of the world, as Roumania and Hun-<br />

gary have done.<br />

(October 24): German Jews should not become panicky because<br />

of riots in the Reichstag. "Hitlerism cannot prevail in the Reich."<br />

Why not? because<br />

(October 3): The Germans are "not a people who love revolu-<br />

tions."<br />

In 1931, the Nazis suffered a minor setback in a Prussian plebiscite.<br />

While, said the <strong>American</strong> Hebrew, this did not mean the shattering<br />

of the anti-Semitic party, it was a straw in the wind:<br />

(Aupst 21): ". . . . a saner spirit does prevail throughout the en-<br />

tire Reich."<br />

(November 20):-after further Hitler victories-"Comfort is de-<br />

rived from Hitler's conference with Von Hindenburg. He will<br />

stop Hitler through a coalition cabinet. Besides, Germany does<br />

not want to be looked upon as a medieval state. When Hitler<br />

gains representation, he will no longer need the anti-Semitism!"<br />

The sane (or insane) spirit is seen as the determinant of the fate of<br />

the Reich. The need of the ruling classes for a fascist alliance is not<br />

seen, so the conference with Von Hindenburg becomes the chance for<br />

the saner elements to assert themselves. The scapegoat role of the<br />

Jews is recognized. However, it is seen as it was played in an expancl-<br />

ing society: the Jew was often the target for dissatisfied parties (French<br />

Catholics, Socialists, Populists) that were minority groups in the na-<br />

tion. The <strong>American</strong> Hebrew hopes that when the minority Hitler<br />

party gains some success the need for anti-Semitism will cease. How-<br />

ever, it is not seen that Germany, in its chronic crisis, now is ready<br />

for a government-sponsored scapegoat.<br />

Events moved rapidly in<br />

'932<br />

(January 15): There are two possibilities: either the Teutonic<br />

temperament can be trusted or there will be a Hitler triumph<br />

followed by a clash with the Communists.

CRISIS AND REACI ION 93<br />

(March 18):-after Voil Hindenburg was re-elected-"Faith in the<br />

stability and practicality of the German people was restored after<br />

the general elections last Sunday, even among those who, under<br />

the emotional influence of Nazi propaganda, doubted these mo-<br />

mentarily."<br />

(April 15):-after Hitler gained two million more votes-"As the<br />

economic situation over there clears, so will the cohorts of the<br />

Swastika fade from the political picture."<br />

(June 10):-after Von Hindenburg dismissed Bruening and his<br />

cabinet-"Pessimism is warranted. Hitler may get a majority in<br />

the next election."<br />

(November 18):-after the famous election when the votes of the<br />

Nazis declined-'rhis is "a clear recession of the Nazi flood with<br />

indications that it is not likely to rise again to threatening heights<br />

. . . . this result was not unexpected . . . . The only combinations<br />

that can make for defeat of the government are like oil and water<br />

in their principles and cannot coalesce."<br />

Here is the belief that "Teutonic temperament" will allow things to<br />

continue as of yore. Again, the stress on characteristics of a people as<br />

determinants of its history. Social factors are either omitted or mis-<br />

understood: history showed that in politics groups which seemed to be<br />

like oil and water could coalesce.<br />

And the few months just before the tragedy were taken especially<br />

calmly by the <strong>American</strong> HeD~ew:<br />

(February 3):-after Von Hindenburg had appointed Hitler on<br />

January 31st to his cabinet-"\'on Hindenburg has copied Abra-<br />

ham Lincoln (!) and brought the enemy within the camp in order<br />

to control him. The 'irresponsible agitator is taken off the street.'<br />

He will now be chained down to national sanity. Even the Ger-<br />

man Democratic Party's official bulletin states that Hitler is now<br />

'an ex-corporal amidst a count and four barons . . . . under the<br />

supervision of the foxy capitalist, Hugenberg.' "<br />

(March lo):-the Nazi-Nationalist coalition was now in the ma-<br />

jority and there were rumors of the dissolution of the Reichstag<br />

-Should the Reichstag adjourn, anti-<strong>Jewish</strong> legislation would be<br />

less likely with twelve responsible men running the country than<br />

with an assembly of Gjo in charge! "Von Hindenburg-sane, civil-<br />

i7ed. loyal to his constitutional oath-will never descend to the<br />

status of a rubber stamp for Adolph Hitler."<br />

And when Hitler made public his condemnation of further anti-<br />

Semitic practices . . . . ?'his shows he is "attempting to slay the<br />

anti-Semitic beast with unequivocal warning to his followers."<br />

The beast is no longer of \slue now that the Nazis are in power.

94<br />

AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES, JUNE, 1953<br />

The <strong>American</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> Congress is doing a disservice to German<br />

Jewry by demanding mass meetings at this time!<br />

(March 24):-the anti-<strong>Jewish</strong> excesses that could not be denied be-<br />

gan on March 20-The headline: "Outraged world must protest<br />

against Nazi barbarism." "Hitler has failed to subdue the anti-<br />

Semitic beast-German psychology doesn't change its spots."<br />

Down to the very end there is the same false hope, the same misunder-<br />

standing of the Nazi phenomenon. An interesting twist is the confi-<br />

dence in "twelve responsible men" as opposed to 650-that is, demo-<br />

cratic policies are to be achieved by a few intelligent and capable men<br />

at the top of society. And once the excesses have begun, the same fac-<br />

tor that was to prevent them (the German mind) is seen as their cause:<br />

"German psychology doesn't change its spots."97<br />

The crucible of experience clid not alter this interpretation which<br />

the events of 1933 had proved invalid. In the <strong>American</strong> Hebrew of De-<br />

cember 22, 1933, it is pointed out that Hitler had fertile soil in the<br />

German people. Germany never was a civilization in the sense in<br />

which England and America are: "Can one conceive of an Englishman<br />

or an <strong>American</strong> doing what the Germans are now doing? Can one<br />

imagine a Frenchman being so br~ltal?"~s<br />

The belief that a people's spirit is the cause of its good and bad<br />

achievements-an idea very common in the nineteenth century-was<br />

eagerly accepted by the old middle-class. This belief had great value<br />

in assuring the old middle-class Jew that Hitlerism could not happen<br />

here. It was the result of the German spirit, and the <strong>American</strong> spirit<br />

was different.<br />

Social factors were completely overlooked in this group's explaria-<br />

tion. For an adequate social analysis of the rise of fascism would re-<br />

veal that the sort of crisis which makes fascism possible is by no means<br />

limited to a particular country. The slightest implication that such a<br />

phenomenon could occur in the United States was avoided by a re-<br />

jection of the social analysis and the ardent acceptance of the belief<br />

that fascism could appeal only to the people of certain nations, such as<br />

Germany.<br />

Simply being members of America's old middle-class would lead<br />

this group to such an analysis. But its <strong>Jewish</strong> affiliation may have rein-<br />

forced this interpretation. Could what happened to the well-integrated<br />

Herr So-and-so happen to me? This reaction is immediately sup-<br />

pressed by a complete negation of social factors and a seizing on the<br />

German spirit as the explanatory key. Furthermore, there was the des-<br />

perate wish that Hitler is not so; hence, the extreme optimism.<br />

The program of the old middle-class flows from its interpretation<br />

of Nazism and so from its social position. The Voice of America or the

CRISIS AND REACTION 95<br />

Conscience of the World-these expressions of public opinion were<br />

widely hailed by this group as effective weapons against the Nazis. Be-<br />

fore the worst Nazi atrocities, the B'nai B'rith Magazine, in its April-<br />

May, 1933, issue, claimed that public opinion had so far restraincd<br />

Hitler. And after the excesses began, public opinion was deemed the<br />

great chance for the Jews. Publisher Brown of the <strong>American</strong> Hebrew<br />

wrote an article entitled, "Roosevelt and Hoover Can Influence Hit-<br />

ler." The <strong>American</strong> leaders are urged to protest for the sake of Ameri-<br />

can interests in German trade and investments in Germany.99 Related<br />

to the stress on public opinion is the faith in facts. The Anti-Defama-<br />

tion League informed the world that loo,ooo Jews were in the German<br />

army in World War 1.100 This program, of course, flows from the in-<br />

terpretation of Nazism as the result of a people's spirit. Just as a na-<br />

tion has a spirit and a conscience, so has the world. And the United<br />

States, the citadel of freedom for the old middle-class, by its protests<br />

can stir the conscience of the world. When Germany sees that the<br />